Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:21

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Impact of Cooperative Business Management

Curriculum on Secondary Student Attitudes

Gregory McKee & Stacy K. Duffield

To cite this article: Gregory McKee & Stacy K. Duffield (2011) Impact of Cooperative Business Management Curriculum on Secondary Student Attitudes, Journal of Education for Business, 86:6, 357-363, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.542502

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.542502

Published online: 29 Aug 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 292

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.542502

Impact of Cooperative Business Management

Curriculum on Secondary Student Attitudes

Gregory McKee and Stacy K. Duffield

North Dakota State University, Fargo, North Dakota, USAThe authors examined the effect a curriculum about cooperative businesses had on high school student attitudes toward these businesses. Cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions were measured before and after participating in the curriculum. Older high school students increased their attitudes toward cooperatives more than did younger students. Students with prior exposure to cooperatives had increases in positive attitudes toward cooperatives. Larger increases were increased in positive attitudes in female students than male students. Finally, students in regions of North Dakota with relatively fewer cooperatives per square mile had larger increases in positive attitudes.

Keywords: attitudes, cooperative businesses, curriculum, education, gender

A recent study by the University of Wisconsin (Deller, Hoyt, Hueth, & Sundaram-Stukel, 2009) about the national economic impact of cooperatives and the summer 2009 dis-cussion of the role of the cooperative business model in pro-viding health-care services suggests a demand for literacy about how this business model functions. In 2009, approxi-mately 29,285 businesses operated as cooperatives in the U.S. economy (Deller et al.). These cooperatives own$3.1 trillion

in assets, earn $154 billion in annual income, and generate

856,310 full-time jobs, paying $25 billion in wages

annu-ally. Nevertheless, statements by Glozer (Mufson, 2009) and Tonsanger (2009) about how cooperatives could serve the health-care industry, for example, indicate that conflicting concepts about cooperatives pervade the public mind.

In their most traditional sense, businesses are identified as cooperatives based on their ownership, governance, and profit distribution practices (Zeuli & Cropp, 2004). Although recent changes in the laws of some states permit ownership by other groups (Cook & Chaddad, 2004; Paul, 2007), coop-eratives, historically, are owned by their users. Owners con-tribute equity through direct investment, retained profits, or other means. Such equity enables the cooperative to finance its ability to provide goods and services over an extended period of time, and to qualify for loans that provide addi-tional financing. Control over the cooperative is exercised

Correspondence should be addressed to Stacy K. Duffield, North Dakota State University, School of Education, P.O. Box 5057, Fargo, ND 58105, USA. E-mail: stacy.duffield@ndsu.edu

through votes cast by its users. Traditionally, users also elect a board of directors. These are the members’ agents, or repre-sentatives, in the management process. Present demographic trends indicate future demand for employees who understand cooperative business administration. Present management and staff in cooperative businesses are nearing retirement. Many cooperative businesses were started in the decades of the 1910s, 1940s, 1970s, and 1990s, suggesting many present members are unaware of the effort required to start a cooper-ative and changes in the distribution of economic benefits to their communities if the cooperative is replaced by a conven-tional corporation. These conditions are generating increas-ing concern among cooperative business professionals.

The North Dakota economy is served by many coop-eratives. It has the third largest number of agricultural cooperatives of any state in the United States (Deville, Penn, & Eversull, 2009). Almost the entire geographic area of the state is served by telecommunications cooperatives (D. Crothers, personal communication, 2009). There were more memberships in electric cooperatives in 2008 than there were households in the 2000 census (D. Hill, personal communication, 2009). Credit unions serve over 201,000 members, approximately half of North Dakota’s adult popu-lation (National Credit Union Association, 2009). Given that cooperatives are governed by their user–owners, and given that high school students will become the user–owners of the cooperatives in the near future, literacy about the purpose and function of cooperatives is vital if these members eventually make business decisions that continue to allow economic benefits to be created by cooperative businesses.

358 G. McKEE AND S. K. DUFFIELD

To the best of our knowledge, no other studies have been conducted to measure high school student literacy about co-operative businesses in the United States or North Dakota. Anecdotal conversations we had with agricultural education teachers and with state Future Farmers of America adminis-trators suggest that no standardized curriculum exists in the state, and only a handful of teachers present self-developed material about cooperatives.

The present study was designed to measure North Dakota high school student literacy about cooperatives and deter-mine whether participating in a curriculum about coopera-tives would influence student attitudes toward cooperacoopera-tives. Faculty in North Dakota high school career and technical ed-ucation (formerly known as vocational eded-ucation) and U.S. history classes were invited to offer a nine-lesson curricu-lum about cooperative businesses during the fall of 2009. The curriculum was designed to provide basic knowledge about cooperatives through activities that stimulated student and teacher learning about cooperatives. Assessments were used to record changes in student attitudes about cooper-atives. Empirical methods were used to test the hypothesis that students who participate in curriculum about cooperative businesses experience a change in attitude toward coopera-tives, as measured by changes in their cognitive, affective, and behavioral attitude components.

LITERATURE

Attitude

Attitude has been defined as a mental and neural state of readiness to respond, organized through experience, exert-ing a directive and/or dynamic influence on behavior (Reid, 2006). Attitudes are formed in several different ways, includ-ing direct experience. The greater the exposure a learner has toward a subject, the more positive the resulting attitude is likely to be (Petty, Wegener, & Fabrigar, 1997). This complex construct comprises three elements: cognitive (knowledge), affective (feeling), and behavioral (action) elements.

The knowledge and feelings a learner has toward a subject may lead to a commitment to that subject. Gender can also make a difference in attitude and attitude change. In fields traditionally thought of as male specialties, such as math-ematics and computer technology, young women generally have more negative attitudes toward them than young men do (Wilkins & Ma, 2003).

Measuring Attitude

Attitude is viewed as a continuum ranging from positive to negative (Petty et al., 1997), supporting use of a rating scale measurement tool such as a Likert-type scale. Reid (2006) noted several limitations with rating scales: (a) there is no way to ensure equal spacing of the scale, (b) values on one item may not be comparable to those on another item, (c)

correlations assume normality, and (d) similar scores may be obtained for very different attitudinal patterns.

Because attitude is difficult to measure, Reid (2006) cau-tioned researchers not to attempt to prove internal consistency because the items all measure at least slightly different things. Instead, he recommended focusing on validity. Although there is no absolute way to establish validity, sense checks can be made. One way to do this is to compare attitude measures before and after the checks between two different groups.

Reid (2006) warned that “means are meaningless” (p. 13). He strongly discouraged adding up scores to form an attitude score because the items are different and should not be added together. Rather, he recommended analyzing each item separately. Even if analyzing separately, trends and factors may still be apparent.

Impact of Teachers on Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes

Studies have revealed that when teachers are given content training, not only does the teacher’s knowledge increase, but their students’ knowledge about that content also in-creases (Allgood & Walstad, 1999; McCutchen et al., 2002). The same is true for teacher interest: “If the teacher has lit-tle knowledge, interest or enthusiasm toward that subject, a negative attitude may easily be conveyed to the student” (Breen, 2001, p. 64). On the other hand, teachers who show a high interest in a subject may affect the student positively and support learning (Breen; Lazar, Orpet, & Demos, 1973). Because a student’s attitude toward the subject matter de-termines what is learned and retained (Breen), a teacher’s attitude is an important part of the learning process.

Student knowledge and attitudes are open to change and development (Reid, 2006). Lazar et al. (1973) contended that a particular instructional process is likely to facilitate this change. They recommended dividing instructional time into three segments: information delivery, large-group discussion, and small-group discussion groups that look at problem sit-uations presented by the instructor. Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock (2001) went beyond the structure of the lesson and identified nine particular instructional strategies that have been found to promote student learning and achievement including strategies such as summarizing and note taking, identifying similarities and differences, using nonlinguistic representations, and using questioning.

Based on this conceptual framework, we tested the fol-lowing hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1(H1): Changes in high school student attitudes

toward cooperatives would be unaffected by participat-ing in a curriculum about cooperative businesses.

H2: Changes in attitude toward cooperative businesses would

be unrelated to gender.

H3: Changes in attitude toward cooperative businesses would

be unrelated to student year in school.

H4: Changes in attitude toward cooperatives would be

un-related to awareness of interactions with cooperatives prior to participating in the curriculum.

METHOD

Students form attitudes about cooperatives based on their knowledge of, interactions with, and feelings about coop-eratives (Bagozzi & Burnkrant, 1979). The purpose of this study was to determine whether high school students who participate in curriculum about cooperative businesses expe-rience a change in attitude toward cooperatives. We con-ducted a longitudinal analysis comparing student knowl-edge, interactions, and feelings about cooperatives based on a pre- and posttest administered to high school students be-fore and after participating in a curriculum about cooperative businesses.

Lessons were structured in four parts: an introduction to gain foundational knowledge, practice and interaction with content and ideas, an independent and collaborative exten-sion of content and ideas to promote higher level thinking, and a teacher-led wrap-up to connect ideas. Formative and summative assessments were integrated into the lessons. A transmission approach to teaching was avoided in favor of student-directed learning (Powell, 2005). Student learning was supported with graphic organizers, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) text and various web resources.

The unit is standards based, using the national agricultural education standards. The standards were unpacked (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) into unit outcomes, and the lessons were designed with the end goals in mind. Student-centered learn-ing objectives targeted varied levels of thinklearn-ing based on Bloom’s taxonomy. For each lesson, the objectives begin with lower level, foundational thinking, such as identify, de-fine, and describe, and move toward higher level thinking, such as compare and explain.

Activities were designed to integrate the best practices described by Marzano et al. (2001), including determining similarities and differences, summarizing and note taking, providing opportunity for practice, formative assessment for ongoing and timely feedback, and using cueing and question-ing to extend student thinkquestion-ing. Each lesson was intentionally planned to include interaction between students and content and students with peers and teacher. Puzzles and games were included to make the lessons fun for students. Finally, the lessons encourage collaboration among students, which has been found to promote higher levels of learning than individ-ual learning (Marzano et al.).

The lessons were authored by eight North Dakota high school teachers and one college instructor. Teachers met dur-ing a 1.5-day workshop to author the lessons. Teachers were divided into teams of two or three to draft lessons. Then two pairs of teachers reviewed each lesson for completeness and suitability for classroom use. The reviewers provided

sug-gested revisions, and the teachers modified the lessons in response to the suggested revisions. We then compiled the lessons into a single unit and distributed them to interested teachers via mail and website posting.

Changes in student knowledge and feelings about erative businesses and awareness of interactions with coop-erative businesses were measured using a pre- and posttest survey. The survey was divided into four sections. The first section contained 27 questions that measured student knowl-edge about cooperatives. Three modes of questions were used, including multiple-choice, true–false, and open-ended answer. Results are reported as the percentage of correct an-swers.

The second section measured student feelings about coop-eratives. Twelve questions measuring student feelings about cooperatives, based on Garkovich, Bokemeier, Hardesty, Allen, and Carl (1987), Cobia and Navarro (1972), and Torgerson, Plank, and Heffernan (1972), were developed to investigate student feelings about cooperatives. Students in-dicated agreement with statements about their feelings to-ward cooperatives on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Results are reported as a percentage of points out of a maximum of 60.

The third section measured student awareness of their interactions with cooperatives. Students were asked if they were members of cooperatives and whether they had done business with cooperatives. Negative responses were coded as 0 and positive responses were coded as 1 for both ques-tions. Because active members are patrons, by definition, students with interaction question scores greater than zero were categorized as high awareness, whereas students who answered no to both questions were categorized as low awareness. The fourth section included questions to measure demographic information, including year in school, gender, and the class in which the lessons were received.

The population for the student survey was all North Dakota high school students enrolled in agricultural edu-cation and social studies classes during fall 2009. A non-random sample of data was collected from 47 social studies students and 127 agricultural education students. These stu-dents collectively attend 16 high schools scattered across North Dakota and were chosen because their teachers volun-teered to teach the newly developed curriculum.

High school administrators were contacted before deliv-ering the curriculum to the students in order to verify that collecting data about changes in student attitude would be consistent with school policy. Students and parents were in-formed of the study and were assured that, although pre- and posttests would be linked to the same student, student iden-tity would not be recorded. Administrators, students, and their families were also assured that results would be pro-vided only in summary form.

Because of the role of teacher attitudes have in form-ing student attitudes about cooperative, a separate survey

360 G. McKEE AND S. K. DUFFIELD

was administered to teachers to measure their attitudes about cooperatives before teaching the lessons. The survey was divided into four sections. The first section contained 10 questions that measured teacher knowledge about cooper-atives. Only open-ended answer type questions were used. The second section measured teacher feelings about cooper-atives. Sixteen questions about teacher feelings toward coop-eratives, based on Garkovich et al. (1987), Cobia and Navarro (1972), and Torgerson et al. (1972), were developed to in-vestigate teacher feelings about cooperatives. Yes–no type questions were used. The third section measured teacher interactions with cooperatives. This section included 12 yes–no type questions asking whether teachers had partic-ipated in a range of activities with cooperatives. The fourth section included questions to measure demographic informa-tion, including age, gender, level of educainforma-tion, and teaching experience.

The teacher survey was administered on surveymon-key.com. Composite scores for teacher accuracy of knowl-edge and feelings about and interactions with cooperatives were generated. The population for this survey included all high school social studies and agriculture teachers in North Dakota. In 2008, this population included 89 high school agriculture teachers and an unknown number of social stud-ies teachers. Too few teachers (N =15) responded to the survey to provide meaningful statistics from these data. Re-sults from the survey represent 16% of all North Dakota agricultural teachers.

Teachers submitted completed student pre- and posttests. We graded the knowledge section of the tests, and then recorded the number correct and responses to Sections 2, 3, and 4 in a database. All hypotheses were tested using depen-dent samplettests using SAS (version 9.2). An alpha level of .05 was used as a critical value for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Approximately 65% of the respondents identified themselves as young men. Approximately 70% of the students identified themselves as juniors or seniors, the remainder as freshman or sophomores.

The first research objective was to measure how high school student knowledge and perceptions toward cooper-ative businesses align before and after participating in a cur-riculum about cooperative businesses. Changes in attitude were based on three components: knowledge, feelings, and awareness. Average student knowledge prior to completing the curriculum was 38.9%. After participating in the cur-riculum, 89.4% of students increased in their knowledge. The average increase in knowledge was 23% relative to their knowledge score on the pretest. Increases in knowledge were statistically significant. A decrease in knowledge about co-operatives was expressed in 8.4% of students on the posttest as compared to the pretest. It is unclear whether this reflects

an actual decrease in understanding or in the level of effort exercised by students in completing the survey.

The average student feelings toward cooperatives score prior to completing the curriculum was 59 (SD =0.131). An increase in the feelings score was experienced by 56.4% of students, with the average increase being 4.8 relative to the pretest. Increases in the feelings score were statistically significant for the entire sample. A decrease in the feelings toward cooperatives score was expressed by 33% of students on the posttest as compared with the pretest, with an aver-age decrease of 12.7%, larger than the averaver-age increase in the feelings score. Students with decreased feelings scores had smaller than average (21.6%) increases in knowledge, whereas students with increased feelings scores had larger than average (24.3%) increases in knowledge.

Finally, 54.6% of students indicated high awareness about interacting with cooperatives at the start of the curriculum. This number increased for 38% of students, and decreased for 9.5% of students at the end of the curriculum. This indicates that at the time students started the curriculum, more than one third of students either were members of or had done business with cooperatives and did not realize it, or had made a deliberate effort to conduct business with cooperatives by the time they completed the posttest. A smaller group came to realize they either were not members of cooperative or had not done business with them.

Together, these results indicate that the lessons statistically increase high school student attitudes about cooperatives. Knowledge of, feelings about, and awareness of interacting with cooperatives statistically increased for most students after participating in the curriculum.

Gender

The null hypothesis that changes in student attitudes about cooperatives were unrelated to gender was tested. Average knowledge was 38.4% for young men and 39.7% for young men prior to participating in the curriculum. The curriculum resulted in increases in knowledge for 92.2% of young men (n=115) and 87.1% of young men (n=62) students. The av-erage increase in knowledge for young men was 21.1% and 26.4% for young women. Increases for both genders were statistically significant and statistically different from each other. Hence, female students knew more about cooperatives before participating in the curriculum, and learned more than their male student counterparts during the curriculum. To the extent knowledge about business management is a subject dominated by young men, this result is contrary to the lit-erature cited previously about young women in traditionally male-dominated areas. A possible explanation for this result may include differences in aptitude between young men and young women in the sample. No data were gathered to test this.

There were not statistically significant differences in changes in feelings scores between genders (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Dependent SampletTest on Attitude Change Toward Cooperatives, by Gender

Student attribute Start End Change t p

Young women (n=62)

Knowledge 0.396 0.660 0.264

∗

11.31 (df=61) <.001

Feeling 0.599 0.632 0.033∗ 2.22 (df=61) .030

Awareness of interaction 0.605 0.798 0.194

∗

6.81 (df=61) <.001 Young men (n=115)

Knowledge 0.384 0.596 0.211∗ 15.56 (df=114) <.001

Feeling 0.585 0.642 0.057 1.55 (df=114) .124

Awareness of interaction 0.691 0.746 0.053

∗

2.23 (df=114) .028

∗p<.05.

However, changes in awareness of experience with coop-eratives varied by gender. Average awareness was 69.1 (SD

=0.210) for young men and 60.5 (SD=0.154) for young women. After completing the posttest, an increased degree of awareness about dealing with cooperatives was indicated by 29.6% of young men and 54.8% of young women. Increases for both genders were statistically significant and statisti-cally different from each other. Hence, a larger increase in the positive attitudes of female students over male students was observed, and the null hypothesis cannot be rejected.

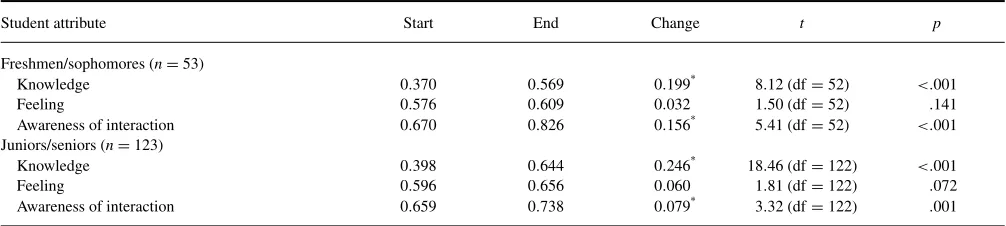

Age

The null hypothesis that changes in student attitudes about cooperatives were unrelated to age was also tested. Aver-age knowledge was 37% for freshmen and sophomores and 39.8% for juniors and seniors prior to participating in the curriculum. Taking the curriculum increased knowledge for 84.9% of freshmen and sophomores (n=53) and 93.5% of juniors and seniors (n=123). The average increase in knowl-edge for freshmen and sophomores was 19.9% and 24.6% for juniors and seniors. Increases for both age groups were sta-tistically significant, but not stasta-tistically different from each other (p=.0609), indicating that juniors and seniors learned statistically the same amount as freshmen and sophomores participating in the curriculum.

Statistically significant differences in changes of feelings toward cooperatives scores within and between age groups were observed (Table 2). Average feeling was 57.6 (SD=

0.132) for freshmen and sophomores and 59.6 (SD=0.132) for juniors and seniors prior to participating in the curriculum. Sixty-six percent of freshmen and sophomores and 53.7% of junior and senior students experienced an increase in feelings toward cooperatives, with the average increase being 0.03% (SD=0.158) for freshmen and sophomores and 0.06% (SD=

0.368) for juniors and seniors. The increase in feelings scores was statistically significant for juniors and seniors. Changes in feelings scores were statistically different between the two age groups. Hence, older students had significantly higher feelings scores and increased them by more than younger students.

Changes in awareness of experience with cooperatives varied by age. Average awareness was 67 (SD=0.182) for freshmen and sophomores and 65.9 (SD=0.203) for juniors and seniors. An increased degree of awareness about deal-ing with cooperatives was indicated by 47.2% of freshmen and sophomore and 35.0% of junior and senior students. The average increase in awareness of interaction was 15.6 for freshmen and sophomores and 7.9 for juniors and seniors. Increases of awareness were statistically significant for both age groups, and the increases for each age group were sta-tistically different from each other, indicating that after the

TABLE 2

Dependent SampletTest on Attitude Change Toward Cooperatives, by Age

Student attribute Start End Change t p

Freshmen/sophomores (n=53)

Knowledge 0.370 0.569 0.199∗ 8.12 (df=52) <.001

Feeling 0.576 0.609 0.032 1.50 (df=52) .141

Awareness of interaction 0.670 0.826 0.156

∗

5.41 (df=52) <.001 Juniors/seniors (n=123)

Knowledge 0.398 0.644 0.246∗ 18.46 (df=122) <.001

Feeling 0.596 0.656 0.060 1.81 (df=122) .072

Awareness of interaction 0.659 0.738 0.079

∗

3.32 (df=122) .001

∗p<.05.

362 G. McKEE AND S. K. DUFFIELD

TABLE 3

Dependent SampletTest on Attitude Change Toward Cooperatives, by Membership Awareness

Student attribute Start End Change t p

Nonmember (n=62)

Knowledge 0.370 0.602 0.232

∗

11.99 (df=61) <.001

Feeling 0.581 0.608 0.026 1.16 (df=61) .249

Awareness of interaction 0.500 0.731 0.231∗ 9.60 (df=61) <.001 Member (n=115)

Knowledge 0.410 0.636 0.227

∗

14.47 (df=114) <.001

Feeling 0.609 0.669 0.060 1.94 (df=114) .141

Awareness of interaction 0.816 0.795 –0.021∗ –1.02 (df=114) .312

∗p<.05.

curriculum freshmen and sophomores became significantly more aware of their relatively larger number of interactions with cooperatives than juniors and seniors.

Hence, the results suggest that juniors and seniors ex-perience different increases in positive attitudes toward co-operatives than do younger students. Juniors and seniors experienced larger increases in the feelings score, but younger students experienced much larger increases in awareness of interaction with cooperatives. Although rela-tive weights were not assigned to the importance of knowl-edge, feelings, and behavior in the development of attitude, the null hypothesis can be rejected and the conclusion drawn that attitude changes are related to age.

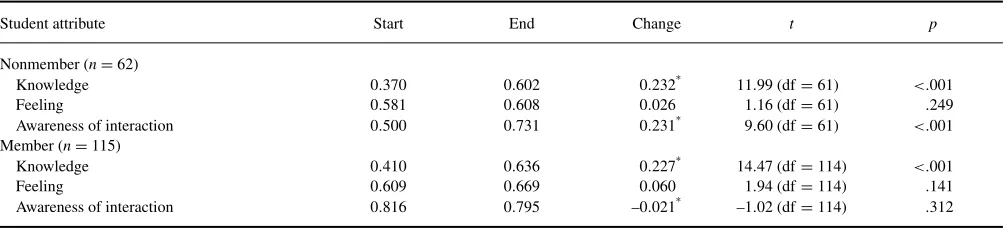

Prior Interaction With Cooperatives

Finally, tests were conducted to examine the null hypothe-sis that prior experience with cooperatives had no effect on changes in attitude toward cooperatives (Table 3). Awareness of prior experience with cooperatives was assessed before and after participating in the curriculum. For purposes of this comparison, pretest observations were the benchmark. Aver-age knowledge was 37% (SD =0.099) for low-awareness students and 41% (SD = 0.116) for high-awareness stu-dents. Participating in the curriculum increased knowledge for 88.6% of low-awareness students (n=79) and 91.6% of high-awareness students (n=95) students. The average in-crease in knowledge for low-awareness students was 23.3% and 22.7% for high-awareness students. Increases for both awareness groups were statistically significant, but not sta-tistically different from each other. High-awareness students learned statistically the same amount as low-awareness stu-dents participating in the curriculum.

There was not a statistically significant difference in the score representing awareness within or between groups. Average feeling was 58.1 (SD=0.099) for low-awareness students and 60.9 (SD=0.127) for high-awareness students prior to participating in the curriculum. An increase in the feelings toward cooperatives score was experienced for 58.2% of low-awareness students and 55.8% of high-awareness students, with the average increase being 0.03%

for low-awareness students and 0.06% for high-awareness students. The increases in the feelings score were not statistically significant for either group, and changes in the feelings scores were not statistically different between the awareness groups.

Change in awareness of experience with cooperatives var-ied by level of awareness prior to participating in the curricu-lum. Average awareness was 50.0 (SD=0.000), the max-imum by definition, for low-awareness students and 81.6 (SD=0.111) for high-awareness students. An increased de-gree of awareness about dealing with cooperatives was in-dicated by 65.8% of low-awareness students and 13.7% of high-awareness students. The average increase in awareness of interaction was 23.1% for low-awareness students, but –2.1% for high-awareness students. Increases of awareness were statistically significant for the low-awareness group, and the increases for each age group were statistically dif-ferent from each other. These results indicate the curricu-lum helped low-awareness students significantly increase their understanding of their interactions with cooperatives, whereas students who were already highly aware of their in-teractions with cooperatives neither thought they were wrong relative to their pretest answer nor realized any additional interactions.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

A large number of baby boomers are presently employed in or are members of cooperative businesses and are nearing re-tirement. This will create new opportunities for another gen-eration to become co-op employees and members, yet little education is provided to high school students about this ness model. The curriculum created about cooperative busi-nesses was created for high school students, the new genera-tion of potential co-op employees and members. In general, participation in the lessons statistically increased high school student attitudes about cooperatives. Knowledge of, feelings about, and awareness of interactions with cooperatives sta-tistically increased for most students. However, the degree of change in attitude depended on various factors. Larger

increases in positive attitudes occurred in female students than in male students, corresponding to increased knowledge and awareness of experiences with cooperatives. Older high school students experienced larger increases in positive feel-ings scores, but younger students experienced much larger in-creases in awareness of interactions with cooperatives and an equal increase in knowledge. Finally, awareness of prior in-teraction with cooperatives also affects the degree of change in attitude. Awareness of interactions with cooperatives in-creased regardless of the size of cooperatives or membership status. Positive feelings, however, are statistically greater in areas with larger cooperatives than smaller ones. Questions remain about the level of student effort applied to the pre- and posttest.

These results suggest that a standards-based curriculum can have a positive effect on the attitudes of high school stu-dents toward cooperative businesses. Improvement occurred through increased cognition, increased affection toward co-operatives, and an increase in awareness of interaction with cooperatives. Students can then apply the increased positive attitude toward future participation in cooperative businesses, either through employment or membership. The data indicate this may be particularly effective in areas with few cooper-atives and may aid students who have had little to no prior interaction with cooperatives.

REFERENCES

Allgood, S., & Walstad, W. (1999). The longitudinal effects of economic education on teachers and their students.The Journal of Economic Edu-cation,30, 99–111.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Burnkrant, R. E. (1979). Attitude organization and the attitude–behavior relationship.Journal of Personality and Social Psy-chology,37, 913–929.

Breen, M. J. (2001). Teacher interest and student attitude toward four areas of elementary school curriculum. School Psychologist, 35, 63– 66.

Cobia, D., & Navarro, L. A. (1972).How members feel about cooperatives. Department of Agricultural Economics, Fargo, ND.

Cook, M. L., & Chaddad, F. R. (2004). Redesigning cooperative bound-aries: The emergence of new models.American Journal of Agricultural Economics,86, 1249–1253.

Deller, S., Hoyt, A., Hueth, B., & Sundaram-Stukel, R. (2009). Re-search on the economic impact of cooperatives. University of Wiscon-sin Center for Cooperatives. Retrieved from http://reic.uwcc.wisc.edu/ sites/all/REIC FINAL.pdf

Deville, K., Penn, J., & Eversull, E. (2009).Cooperative statistics 2008. Service Report 69. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Rural Development.

Garkovich, L., Bokemeier, J., Hardesty, C., Allen, A., & Carl. E. (1987). Farm women and agricultural cooperatives in Kentucky. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture.

Lazar, A. L., Orpet, R., & Demos, G. (1973).The impact of class instruc-tion in changing student attitudes. Long Beach, CA: California State University.

Marzano, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Pollock, J. E. (2001).Classroom in-struction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curricu-lum Development.

McCutchen, D., Abbott, R. D., Green, L. B., Beretvas, S. N., Cox, S., & Potter, N. S. (2002). Beginning literacy: Links among teacher knowledge, teacher practice and student learning.Journal of Learning Disabilities, 35, 69–86.

Mufson, S. (2009, August 27). Cooperatives’ record is up for debate; some herald them as cure for health care; others question their power, costs. Washington Post, A18. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/ wp-dyn/content/article/2009/08/26/AR2009082603485.html

National Credit Union Association. (2009).Financial performance report. Various issues. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Paul, D. (2007). Wisconsin adopts second cooperative statute: The Wiscon-sin cooperative associations act.Ag Co-Op News, February.

Petty, R. E., Wegener, D., & Fabrigar, L. R. (1997). Attitudes and attitude change.The Annual Review of Psychology,48, 609–647.

Powell, S. D. (2005).Introduction to middle school. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Reid, N. (2006). Thoughts on attitude measurement.Research in Science and Technical Education,24(1), 3–27.

Tonsanger, D. (2009).Rural America runs on co-ops. Rural cooperatives, September, October 2009. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Agricul-ture, Rural Development.

Torgerson, R. E., Plank, S. C., & Heffernan. W. D. (1972).Farm op-erators’ attitudes toward cooperatives. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri–Columbia.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005).Understanding by design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice-Hall.

Wilkins, J. L., & Ma, X. (2003). Modeling change in in student attitude toward and beliefs about mathematics.Journal of Educational Research, 97, 52–64.

Zeuli, K. A., & Cropp, R. (2004).Cooperatives: Principles and practices in the 21st century. Publication A1457. Madison, WI: University of Wis-consin Extension.