Relationship between leadership

behaviors and performance

The moderating role of a work team’s level of

age, gender, and cultural heterogeneity

Jens Rowold

TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany

Abstract

Purpose– In today’s organizations, the heterogeneity of work teams is increasing. For example, members of work teams have different ages, genders, and/or cultural backgrounds. As a consequence, team leaders have to face the challenge of taking into account the various needs, values, and motives of their followers. However, there has been very little empirical research to test whether the influence of leadership behaviors on performance is moderated by facets of team heterogeneity. This paper aims to address this issue.

Design/methodology/approach– The leadership behaviors of transactional and transformational leadership, laissez-faire, consideration, and initiating structure, as well as three facets of heterogeneity (i.e. age, gender, and culture) were assessed in an empirical study based on a sample ofn¼283 members

of German fire departments. These team members also provided self-ratings for their performance.

Findings– The results revealed that the relationship between three leadership behaviors (i.e. transformational leadership, laissez-faire, and consideration) and performance was being moderated by facets of team members’ heterogeneity.

Practical implications– Both transformational leadership and consideration work best when the work team is heterogeneous with regard to gender.

Originality/value– The importance of the contextual influences of team members’ heterogeneity for effective leadership processes was explored theoretically, and subsequently, demonstrated empirically for the first time.

KeywordsLeadership, Heterogeneity, Team, Performance management

Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

Over the last decade, important advancements have been made contributing to our understanding of effective leadership. For example, we know a great deal about the effectiveness of various leadership behaviors, based on results of meta-analysis

(Dumdumet al., 2002; Judgeet al., 2004). However, although recent theoretical works

have emphasized the context sensitivity of leadership (Conger, 2007; Hunter et al.,

2007), empirical research in this field is still rare. That is, the contextual conditions under which the leadership-effectiveness relationships hold true are not yet fully explored. As a consequence, scientists as well as practitioners still cannot recommend specific leadership behaviors to organizational leaders for certain situations with any

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0143-7739.htm

Part of this research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, No. Ro 3058/2-1, principal investigator: Jens Rowold). The author would like to thank Christina Wohlers and Kathrin Staufenbiel for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

LODJ

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited 0143-7739

great certainty, as knowledge in this field is fragmentary (Yukl, 2002). This gap in the literature calls for research on the important area of the contextual dimensions of

organizational processes such as leadership (Antonakis et al., 2003; Rousseau and

Fried, 2001). The present study addresses this gap by exploring the moderating effects of different contexts on the relationship between leadership behaviors and performance. More specifically, the focus is on the work team’s level of age, gender, and cultural heterogeneity as potential moderators of the leadership-performance relationship.

In general, leadership research focuses on one leadership paradigm at a time, although the considerable theoretical overlap between these theories has been discussed (Rowold and Heinitz, 2007; Graenet al., 2010). Thus, recent calls for research strongly suggested the need to compare and contrast leadership theories with each other (Yukl, 1999, 2002). It should be noted that in contrast to virtually all prior empirical studies, the present one includes several leadership paradigms. Most researchers agree that one specific leader can exhibit several leadership behaviors over time, although in one specific situation, the focus is typically on one leadership behavior (Bass, 1985; Blake and Mouton, 1964).

First, we discuss the leadership behaviors relevant for the present study. Second, as the present paper focuses on the heterogeneity of the work team, this context factor is introduced. Next, the contextual sensitivity of the leadership behaviors is explored. Furthermore, a theoretical model is developed, proposing both:

. the main effects of leadership behaviors; as well as

. the interaction of these leadership behaviors with contextual factors on

performance.

This model is shown in Figure 1. Finally, an empirical study testing this model is conducted. In sum, the present study contributes to our understanding of a hitherto unexplored context factor, namely, facets of heterogeneity of the work team.

Two leadership paradigms

Transformational leadership. Currently, transformational leadership is the most dominating leadership paradigm (Hunt and Conger, 1999; Judge and Piccolo, 2004; Rowold and Heinitz, 2007). Among others, the articulation and representation of a vision based on leaders’ values and ethics is central for this approach to leadership (Bass, 1985; Turneret al., 2002). The transformational leader influences his/her followers by means of a variety of behaviors, so that followers’ values and interests are transformed.

Figure 1.

Summary of hypothesized relationships between the study’s key variables

Leadership Transformational

Transactional Laissez-Faire Consideration Initiating structure

Work team’s heterogeneity: Age, Gender and culture

Performance

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

Ultimately, the followers buy into their leader’s vision and perform beyond expectation. In this process of transformation, the leader has to take the varying values and interests of his/her followers into account. In contrast, transactional leadership has its focus on clearly defined transactions between leaders and followers. For example, the leader defines the task and if the follower accomplishes this task, a previously defined reward is

granted. There is now considerable evidence from meta-analysis (Dumdumet al., 2002;

Judge and Piccolo, 2004) that both transactional and transformational leadership are positively related to various indicators of individual and organizational performance; however, transformational leadership was more strongly associated with performance than transactional leadership. A third leadership behavior, laissez-faire or absence of leadership behavior, was included in the transformational-transactional leadership paradigm (Antonakis and House, 2002). Meta-analysis clearly documented negative relationships between laissez-faire and indicators of performance. Some research exists exploring the contextual boundaries of the effectiveness of transformational leadership. For example, meta-analysis provided evidence for the notion that female leaders exhibit

slightly more transformational leadership than their male counterparts (Eaglyet al.,

2003; Powell, 1990). With regard to culture and cultural values, it was found that the effectiveness for transformational leadership is somewhat greater in western countries than in non-western countries (Walumbwa and Lawler, 2003). Finally, empirical research consistently found that the effectiveness of transformational leadership depended on followers’ personality characteristics (Awamleh and Gardner, 1999; Felfe and Schyns, 2005).

Consideration and initiating structure. In the two decades prior to the rise of transformational leadership theory, several important leadership theories such as Fiedler’s (1967) contingency approach, House’s (1971) path-goal theory, consideration and initiating structure (Fleishman, 1973) dominated the field. However, because the inclusion of all of these theories was beyond the scope of the present study, the focus was on the paradigm of consideration and initiating structure. The key characteristic of consideration is the supportive, “people-oriented” behavior the leader shows toward each follower. This implies positive attributes such as trust, respect and open communication in the relationship between leader and led. In contrast, initiating structure emphasizes behaviors, such as structuring the work task, making assignments, and setting task-related goals. In a recent meta-analysis, it was found that both leadership behaviors have positive criterion-oriented validity ( Judgeet al., 2004). Also, it was revealed that with regard to subjective performance indicators, consideration had roughly the same criterion-oriented validity as transformational leadership. Thus, the question emerges whether the leadership behaviors of transformational leadership and consideration might rely on partly identical motivation processes (e.g. considering followers’ needs). However, before firm conclusions can be drawn, more integrative research is needed to compare and contrast the rivaling effects of these two leadership behaviors on criteria of effective leadership ( Judgeet al., 2004; Judge and Piccolo, 2004).

Little empirical research has explored the context sensitivity of consideration and

initiating structure. For example, the meta-analysis conducted by Judgeet al. (2004)

found that the criterion-oriented validity of both leadership behaviors was neither moderated by:

. leader’s hierarchical level in the organizations; nor

. the type of organization.

LODJ

32,6

However, considerable theoretical work which suggests additional context factors (e.g. characteristics of the work team) for both consideration and initiating structure, have not been tested yet ( Judgeet al., 2004; Schruijer and Vansina, 2002; Yukl, 2002).

Overview of the theoretical model

Comparing leadership styles. The model guiding the development of hypotheses of the present study is shown in Figure 1. As can be seen, direct relationships between leadership behaviors and performance were included in this model. Thus, the following hypothesis is in accordance with prior theoretical and empirical research ( Judgeet al., 2004; Judge and Piccolo, 2004):

H1. Five leadership behaviors are significantly associated with performance.

For transactional (H1a), transformational (H1b), consideration (H1d), and initiating structure (H1e), this relationship will be positive, while for laissez-faire (H1c), it will be negative.

This hypothesis compares the competing effects of several leadership behaviors on performance. For example, it has been argued from theory that considerable overlap between transformational leadership and consideration exists ( Judge, 2005; Judgeet al., 2004; Yukl, 2002). In fact, one facet of transformational leadership is labeled “individualized consideration” and mainly reflects the content of the leadership behavior of consideration. Thus, it might be asked critically whether the strong direct effects of the leadership behaviors of transformational leadership on performance might be at least partially redundant to the direct effects of consideration. Owing to the fact, that the critical question concerning the amount of overlap between the leadership behaviors has not yet been tested empirically, research in this area seems warranted.

Thus,H1explores the unique, relative criterion validity of five leadership behaviors.

In addition to these unique relationships between leadership behaviors and performance, the present study explored whether these relationships are moderated by a contextual factor, namely, heterogeneity of the work team.

Facets of heterogeneity of the work team as a context factor

In general, there has recently been an increase in research activity regarding context and leadership. However, we are still far from having a thorough understanding of the effects of context factors and how they moderate the relationship between leadership behaviors and outcome criteria (Yukl, 2002). One reason for this is that numerous contextual factors exist. Among others, examples of contextual factors are: characteristics of the organizations (e.g. profit vs non-profit; Rowold and Rohmann,

2009), the leader (e.g. communication skills, Freseet al., 2003; gender, Rohmann and

Rowold, 2009), the follower (e.g. cultural orientation, Walumbwa et al., 2007).

Additionally, characteristics of the work team have been discussed by leadership researchers (Eisenbeisset al., 2008) as an important contextual factor.

One characteristic of the work team is their respective level of heterogeneity. Over the last decades, work teams have become more and more heterogeneous, yielding new problems for organizational leaders and leadership scholars. An example is the problem of intragroup conflicts, lack of mutual trust, and miscommunication hampering the performance of heterogeneous teams. Thus, far, a few empirical studies have addressed

this leadership challenge. First, Mayoet al.(1996) found heterogeneous work teams

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

having lower performance, as rated by the respective leader, than homogeneous work teams. Also, the amount of heterogeneity of work teams was negatively related to leader’s self-efficacy. Second, based on a sample of primary care work teams working in public hospitals, Somech (2006) reported that within highly functionally heterogeneous teams, participative leadership behavior was positively associated with team reflection and innovation, which are two indicators of team performance.

Boone et al. (2005) studied managers participating in a simulation exercise and

found that highlocusof control heterogeneity of work team impacts performance. In

sum, these studies demonstrate the importance of the context factor of team heterogeneity (Shin and Zhou, 2007; Somech, 2006). However, we have very cursory knowledge about the relationship between leadership behaviors and performance moderated by this context factor. Thus, research seems necessary to demonstrate to scientists and practitioners which leadership behavior is effective for heterogeneous work teams.

Heterogeneity of the work team can be defined by various characteristics. For the purpose of the present study, we focused on three facets of heterogeneity: three facets of heterogeneity, i.e. team members’ age, gender, and cultural background, have recently been discussed in the literature (Yukl, 2002). Likewise, as a consequence of recent demographic and labor market trends, these facets of the work team’s heterogeneity are relevant for almost all kinds of modern organizations. As for age, the current workforce is getting increasingly older. This development means that organizational behavior research is challenged to test whether hitherto established relationships between constructs hold for teams, which are:

. on average, older; or

. heterogeneous with regard to age (Maurer, 2001; Warr and Fay, 2001).

Next, an increasing proportion of female employees can be found in today’s organizations. Also, due to global markets and international joint ventures, the number of employees with different cultural backgrounds working together in teams has been increasing.

How do leadership behaviors operate in heterogeneous work teams?

This section provides rationales for the expected moderating effects of a work team’s heterogeneity on the relationship between the above-mentioned leadership behaviors and performance. For each leadership behavior of transactional and transformational leadership, laissez-faire, consideration and initiating structure, it is described why heterogeneity of the work team might impact the effectiveness of the respective leadership behavior.

Transactional leadership. Typically, transactional leaders set explicit, work-related goals and the rewards that can be expected as a result of performing successfully. Within this definition of transactional leadership, it is the implication that this is not done proactively and in close cooperation with each team member (Avolio and Bass, 1995). As each team member has different needs and abilities, especially in heterogeneous work teams, the leader should set clear and explicit goals with each team member individually. However, high demands and workloads often prevent transactional leaders from providing this individual considerate behavior (Bass, 1985). Thus, goals and rewards are often communicated for the group as a whole. As the work team’s heterogeneity increases,

LODJ

32,6

this may lead to misunderstandings on the part of the team members, as each individual team members may have different backgrounds, experiences, values, and work routines

(Erdogan et al., 2004). It might therefore be difficult to understand the goal thing

communicated by the leader, thus resulting in low performance. In contrast, in homogeneous work teams, goals can be presented efficiently, as every team member shares the same background of, experience and values, among others. In sum, it was expected that transactional leadership works best in homogeneous work teams:

H2. The relationship between transactional leadership and performance will be

moderated by work team heterogeneity, so that the relationship will be stronger in homogeneous teams than in heterogeneous ones.

Transformational leadership. In contrast to their transactional counterparts, transformational leaders communicate higher order values and explicit work tasks to each team member individually (Bass, 1985). The leader assesses each team member’s background, values and motives in order to formulate a common vision of a better future. Likewise, individual differences are acknowledged and appreciated. This implies that in heterogeneous work teams, where each team member has different backgrounds, values, and motives, the leader tries to find the common ground and thus, establishes values for an optimal cooperation between the members of the work team. These values typically transcend age groups and other demographic characteristics. For example, the ideal of fairness is valid for most employees, regardless of demographic characteristics. By means of this transformational process, team members find orientation and are provided with a set of values. Consequently, these explicated, commonly shared, work-related values help them when making difficult decisions under conditions of high uncertainty (Bass and Steidlmeier, 1999). In the long run, this process may well yield high performance.

These ideas are supported by the team diversity literature. For example, Polzeret al.

(2002) found that heterogeneous teams are likely to develop into cohesive teams. Jehn

et al. (1999) made the distinction between social category (e.g. demographic characteristics), value, and information diversity. These authors reported that social homogeneity had a positive impact on teams’ levels of morale. Also, this study found that teams with heterogeneous values had lower levels of team commitment (Harrison

et al., 2002). Owing to the fact that transformational leaders focus on commonly shared values and foster the acceptance of group values, this leadership behavior represents a way to foster positive team outcomes such as commitment and performance.

It has been noted that heterogeneous work teams have the opportunity to provide a competitive advantage over and above homogeneous work teams, if these

heterogeneous teams are managed properly (DiTomaso et al., 1996; Haro, 1993).

Transformational leadership is one effective way to manage heterogeneous work teams, as the potential of the heterogeneous team members is acknowledged, valued, and utilized to attain high performance ( Jung and Avolio, 2000). As an example, transformational leaders display intellectually stimulating behavior in order to reach high-performance goals. In the process of intellectual stimulation, each team member’s own way of thinking and solving problems is encouraged and used to find new solutions for work-related problems. As the probability of finding new solutions increases with the degree of team members’ heterogeneity (e.g. way of thinking), transformational leadership is more effective in heterogeneous work teams:

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

H3. The relationship between transformational leadership and performance will be moderated by work team heterogeneity, so that the relationship will be stronger in heterogeneous teams than in homogeneous ones.

Laissez-faire leadership. As was stated above, laissez-faire is basically the absence of leadership. Teams which are not led face considerable difficulties (Yukl, 2002). Often, these teams have to compensate for the missing leadership in order to reach goals. It might be argued that due to their team members’ wide ranges of skills, abilities and experiences, heterogeneous leaderless teams can compensate better for the absence of leadership than their homogeneous counterparts:

H4. The relationship between laissez-faire and performance will be moderated by

work team heterogeneity, so that the relationship will be stronger in heterogeneous teams than in homogeneous ones.

Consideration. Considerate leaders can help each subordinate individually to understand goals, tasks, etc. yielding higher performance. Heterogeneous team members act upon and utilize considerate leadership behavior from their respective team leaders, because each team member with his/her respective values and abilities needs individualized help in reaching goals and completing tasks. For example, young workers who have not been acquainted with certain work routines need explicit guidance and leadership from their leaders, while older workers have enough experience to solve work-related problems with less help from their supervisor. In this scenario, the supervisor needs to act with individualized consideration. In contrast, in homogeneous teams, consideration might not be necessary since all team members need the same kind of guidance or leadership behavior in order to reach work-related goals:

H5. The relationship between consideration and performance will be moderated

by work team heterogeneity, so that the relationship will be stronger in heterogeneous teams than in homogeneous ones.

Initiating structure. Like transactional leadership, initiating structure focuses on defining tasks, routines, structures (e.g. scheduling) and rewards. For homogeneous teams where each team member has the same experiences and background, this leadership behavior may be sufficient. In contrast, in the case of heterogeneous teams, the definition of task, etc. might lead to confusion if team members are not guided individually. Thus, it is expected that only in work teams characterized by low heterogeneity, will the leadership behavior of initiating structure result in high performance:

H6. The relationship between initiating structure and performance will be

moderated by work team heterogeneity, so that, the relationship will be stronger in homogeneous teams than in heterogeneous ones.

Controlling for leader’s hierarchical level

Finally, the factor of leader’s hierarchical level was included in the present study as one of the control variables that have been discussed in the leadership literature (Antonakis and Hooijberg, 2007; Antonakis and House, 2002; Yukl, 2002). For example, empirical research exists which has found varying levels of transformational leadership on

LODJ

32,6

different levels of the organization (Loweet al., 1996). For this reason, this context factor is controlled for in the analyses.

Methods

Sample and procedure

A research assistant prepared a list with information about 700 fire departments in Germany, based on data from a web search. These departments were contacted and information about the background and the goals of the study was provided. Surveys were

sent to then¼426 departments who agreed to take part in the study. Participants were

members from various levels of these fire departments. A total ofn¼283 individual

subjects from the various departments responded (response rate¼66.4 percent). These

participants assessed the leadership behavior of their respective direct leader. The mean

age of the participants was 33.8 years (SD¼11.6); their mean tenure was 14.3 years

(SD¼10.9); 88.9 percent were male. Overall, 54.5 percent had a junior and 24.4 percent a

senior high school diploma. Also, 21.1 percent had a university degree. As for the leaders,

96 percent were male; these leaders had an average tenure of 23.8 years (SD¼10.8).

Overall, 10.1 percent of the leaders were first-level supervisors. These supervisors led, for example, one fire truck team. Nearly one fourth (24.9 percent) of the leaders were branch-level supervisors and had responsibility for one field of expertise (e.g. material support, engineering, etc.). Finally, the remaining 63.6 percent of the leaders were heads of the respective departments, guided their respective branch-level supervisors and had additional administrative responsibilities. For reasons of confidentiality and anonymity, neither the name of the participant nor the name of the respective fire department was assessed, so that, individual responses could not be assigned to one specific department.

Instruments

Transactional and transformational leadership. Four items from a German validated version (Heinitz and Rowold, 2007) of the transformational leadership inventory (Podsakoffet al., 1996b; TLI; cf. Podsakoffet al., 1990) were utilized to assess transactional leadership (sample item: “[...] provides me with positive feedback if I perform well”). Also,

22 items from the TLI were utilized for the assessment of transformational leadership (sample item: “[...] has inspiring plans for the future”).

Laissez-faire. For the assessment of laissez-faire, four items were newly designed (sample item: “[...] tries to avoid decisions”).

Consideration and initiating structure. The leadership behavior of consideration was assessed by 22 items from a German validated version (Fittkau-Garthe and Fittkau, 1971) of the SBDQ (Fleishman, 1953) (sample item: “[...] shows interest in the individual

well-being of his/her subordinates”). Finally, initiating structure was assessed by 12 items from the same questionnaire (sample item: “[...] assigns specific tasks to his/her

subordinates”). For all leadership items, the frequency of observed leadership behavior was assessed using a five-point Likert-scales (1 – never, 5 – always).

Performance. Four items were newly constructed in order to assess subordinates self-rated performance (e.g. “My job performance is high”). The five-scale anchors ranged from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

Facets of heterogeneity. Each facet of work team heterogeneity was assessed by one dichotomous item, respectively. Thus, participants revealed whether their respective work team had low or high levels of:

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

. age heterogeneity;

. gender heterogeneity; and

. cultural background heterogeneity.

Discriminant validity of constructs

In order to provide insight into the relative independence of the construct utilized in the present study, confirmatory factor analysis was applied. A measurement model was tested that included each of the leadership constructs and performance (i.e. in sum, six constructs), with their respective indicators. To assess the condition of multivariate normality of the data, an omnibus test based on Small’s statistics (Looney, 1995) was performed. The results showed a significant violation of the multivariate normality (x2¼864.02, df¼132,p,0.001). To account for the missing multivariate normality,

the parameters of the proposed model are estimated using the unweighted least squares discrepancy function (Byrne, 2001; Xime´nez, 2006). The fit indices revealed

that the proposed measurement model showed a good fit to the data (x2¼1,536.63,

SE¼8.32; df¼2,071; GFI¼0.96; AGFI¼0.96; cf. Hu and Bentler, 1999). A more

parsimonious one-factor model also yielded a good fit to the data (x2¼1,474.56,

SE¼7.61; df¼2,079; GFI¼0.95; AGFI¼0.95). However, in comparison, the

absolute fit indices of GFI and AGFI were in support of the measurement model

(Cheung and Rensvold, 2002). While the x2-difference test revealed no significant

differences between these two models (Dx2¼62.07,Ddf¼8,p.0.05), it should be

noted that this test has been criticized because it might be biased with regard to sample size (Bentler, 2004). Thus, it was concluded that the various constructs used in the present study had adequate discriminant validity.

Results

Table I contains descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of the study’s variables. The internal consistency estimates for leadership behaviors and self-rated performance were satisfactory. As can be seen from this table, four of the five leadership behaviors were positively associated with self-rated performance. One might ask whether differences in performance exist between heterogeneous versus homogeneous teams. However, no significant effects in levels of performance were detected. for any of the three facets of heterogeneity.

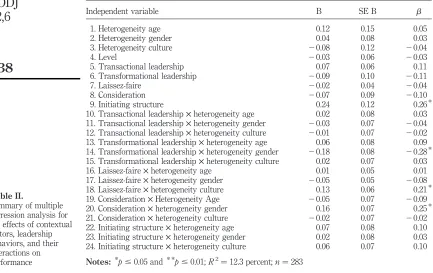

Multiple regression analysis was performed to test the influences of leaders’ hierarchical level, contextual factors, leadership behaviors, and the interaction terms between contextual factors and leadership behaviors on performance. In accordance

with the methodological standards of regression (Cohen et al., 2002), the leadership

behaviors and context factors were standardized prior to computing their interactions, which were subsequently entered into the regression analysis. No signs of

multicollinearity were detected (i.e. the VIF was below or equal 5; cf. Belseyet al.,

1980; Cohenet al., 2002).

The results of the multiple regression analyses were summarized in Table II. None of the control variables was significantly related to performance. Furthermore, the only leadership behavior that was associated with performance was initiating structure.

Thus, only H1 was confirmed. Concerning the interactions between leadership

behaviors and facets of work teams’ heterogeneity, several hypotheses could be confirmed. First, the interaction between transformational leadership and gender was

LODJ

32,6

Variable MW SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

(1) Heterogeneity age 1.91 0.29 –

(2) Heterogeneity gender 1.47 0.50 0.22* * –

(3) Heterogeneity culture 1.15 0.36 0.06 0.11 – (4) Level 2.55 0.67 0.18* * 0.16* * 20.04 –

(5) Transactional leadership 3.15 1.01 0.06 20.08 20.03 20.05 0.83

(6) Transformational leadership 3.28 0.78 0.04 20.13* 20.10 20.08 0.77* * 0.94

(7) Laissez-faire 2.09 1.10 20.04 0.03 0.05 0.10 20.37* * 20.47* * 0.90 (8) Consideration 3.42 0.85 0.05 20.07 20.09 20.06 0.71* * 0.76* * 20.55* * 0.95 (9) Initiating structure 3.36 0.68 0.08 20.10 20.10 0.03 0.70* * 0.81* * 20.51* * 0.79* * 0.85 (10) Performance 4.07 0.65 0.05 0.03 20.05 0.02 0.15* 0.14* 20.11 0.12* 0.19* * 0.82

Notes:n¼283; values along the diagonal represent internal consistency estimates (Cronbach’sa)

Table

I.

Descriptive

statistics

and

inter-correlations

of

study

variables

Leadership

behaviors

and

performance

significant, lending support toH3. As Figure 2 shows, high levels of heterogeneity and high levels of transformational leadership led to higher levels of performance.

Second,H4gained support from the data as well: the interaction between work team

heterogeneity (culture) and laissez-faire led was significant. As Figure 3 shows, high levels of laissez-faire and high heterogeneity led to high performance.

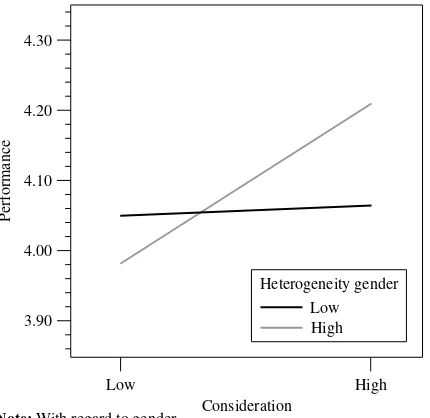

Finally, the interaction between consideration and gender was significant,

supporting H5. The combination of high levels of consideration and heterogeneity

(gender) led to increased performance (Figure 4).

Altogether, 12.3 percent of the variance in performance was explained by context factors, leadership behaviors, and their interactions.

Discussion

Integrative discussion of main results

In general, important contextual conditions of the leadership process have been neglected in prior studies. Addressing this gap, the present study focused on one particular context factor, namely, heterogeneity of the work team. The results revealed that the relationship between several leadership behaviors and performance is moderated by the heterogeneity of the work team.

First, transformational leadership worked best for teams with both male and female employees (i.e. high levels of heterogeneity with regard to gender). It might be argued that transformational leaders can easily create a vision which is based on values that

Independent variable B SE B b

1. Heterogeneity age 0.12 0.15 0.05

2. Heterogeneity gender 0.04 0.08 0.03

3. Heterogeneity culture 20.08 0.12 20.04

4. Level 20.03 0.06 20.03

5. Transactional leadership 0.07 0.06 0.11 6. Transformational leadership 20.09 0.10 20.11

7. Laissez-faire 20.02 0.04 20.04

8. Consideration 20.07 0.09 20.10

9. Initiating structure 0.24 0.12 0.26*

10. Transactional leadership£heterogeneity age 0.02 0.08 0.03 11. Transactional leadership£heterogeneity gender 20.03 0.07 20.04 12. Transactional leadership£heterogeneity culture 20.01 0.07 20.02 13. Transformational leadership£heterogeneity age 0.06 0.08 0.09 14. Transformational leadership£heterogeneity gender 20.18 0.08 20.28*

15. Transformational leadership£heterogeneity culture 0.02 0.07 0.03 16. Laissez-faire£heterogeneity age 0.01 0.05 0.01 17. Laissez-faire£heterogeneity gender 20.05 0.05 20.08 18. Laissez-faire£heterogeneity culture 0.13 0.06 0.21* 19. Consideration£Heterogeneity Age 20.05 0.07 20.09 20. Consideration£heterogeneity gender 0.16 0.07 0.25*

21. Consideration£heterogeneity culture 20.02 0.07 20.02 22. Initiating structure£heterogeneity age 0.07 0.08 0.10 23. Initiating structure£heterogeneity gender 0.02 0.08 0.03 24. Initiating structure£heterogeneity culture 0.06 0.07 0.10

men and women share. For example, values that are highly prevalent in modern day organizations, such as fairness and high quality, could be communicated to both sexes. The paradigm of transactional-transformational leadership prevailed in the leadership literature in the last two decades (Bass, 1998). Interestingly, the level of work teams’ heterogeneity also increased in the same n period. The results of the present study suggest that transformational leadership is one way of dealing with heterogeneous

Figure 2.

Interaction effect for transformational leadership and heterogeneity

4.00

Low

Note: With regard to gender

Transformational leadership 4.10

Performance

4.20 4.30

High High

Low Heterogeneity gender

Figure 3.

Interaction effect for laissez-faire and heterogeneity

3.60 3.80

Low

Laissez-Faire 4.00

Performance

4.20

High

Note: With regard to culture

High Low Heterogeneity culture

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

work teams, because transformational leadership interacts with work teams’ heterogeneity to account for variance in performance.

Second, the present study detected an interaction between laissez-faire and work teams’ heterogeneity (i.e. with regard to culture). This implies that culturally heterogeneous work teams still can perform well, even if the leader is absent (i.e. laissez-faire). These heterogeneous teams compensate for missing leadership – when, due to a high level of laissez-faire, no leadership and guidance is available from the (formal) leader. Third, the interaction between consideration and work teams’ heterogeneity (i.e. with regard to gender) was significantly related to performance. As a speculation, team members of heterogeneous work teams not only elicit individualized considerate behavior from their leaders, but also utilize this one-on-one guidance to achieve work-related goals and high performance. On the other hand, in homogeneous work teams, leaders do not have to act with such consideration, because work-related goals and procedures can be communicated to the group.

Implications for theory

Boundary conditions of effective leadership. The conducted regression analysis represents a more realistic approach to relationships between leadership behaviors and performance, as contextual factors were accounted for. Thus, the present study adds to our knowledge about contextual or boundary conditions for leadership effectiveness. The model that was proposed from theory and shown in Figure 1 is partially supported by the results of the present study. For the advancement of leadership theory, the results of the present study might be utilized to explicate the boundary conditions of the effectiveness of these leadership behaviors: First, in contrast to other leadership styles, transformational leadership is unique, due to its emphasis on vision formulation and communication. This vision process is especially effective if teams consist of both women and men: typically, visions transcend gender-specific roles and cognitions

Figure 4.

Interaction effect for consideration and heterogeneity

3.90 4.00

Low

Consideration 4.10

4.20

Performance

4.30

High

Note: With regard to gender

High Low Heterogeneity gender

LODJ

32,6

(e.g. stereotypes), because visions are rooted in commonly-held values that are behind (or beyond) roles.

Second, the absence of leadership (i.e. laissez-faire) might be compensated for if teams are heterogeneous with regard to cultural background. In general, this result is

in line with the theory of substitutes for leadership (Podsakoffet al., 1996a), which

suggests that certain conditions (e.g. intrinsically satisfying tasks) substitute leadership behaviors. However, the results of the present study went beyond prior research by demonstrating for the first time that cultural heterogeneous teams can compensate for leadership. As a speculation, culturally heterogeneous teams which suffer from laissez-faire, have the potential to form a vision by themselves, because their competing values (e.g. from various cultures) are so predominant. This vision, in turn, yields high team performance. Another possible explanation is that in cultural heterogeneous teams emergent informal leadership is encouraged because the need to find some direction (e.g. basic rules of communication) is highly visible as a consequence of team members’ heterogeneous values.

Third, the core element of consideration (i.e. treating team members on an individual basis), is effective for teams that are heterogeneous with regard to gender. The different gender-specific values, roles, and stereotypes can be addressed by considerate leaders. Individually considerate communication, in particular, helps leaders to assess followers’ values, etc. in the first place. Consequently, the leader can understand and develop means to lead his/her followers to high performance.

As a conclusion, future theoretical work should further develop these preliminary ideas regarding boundary conditions of effective leadership. More specifically, theoretical work should include elements, such as:

. leadership styles;

. followers’ characteristics (e.g. gender); and

. motivational mechanisms (e.g. followers’ stereotypes, leaders’ communication).

Comparing various leadership styles. Prior research demonstrated direct effects of transactional and transformational leadership, laissez-faire, consideration and initiating structure on performance (Dumdumet al., 2002; Judgeet al., 2004). In general, the results (i.e. zero-order correlations) from Table I are in line with these meta-analytic results. However, empirical studies that compared the relative contribution of these leadership behaviors on performance have been rare. The results of the regression analysis (Table II) suggest that these five leadership behaviors might be partially redundant, as not all five behaviors were necessary to explain variance in performance. Interestingly, only one leadership behavior (i.e. initiating structure) showed a direct relationship with performance. As a speculation, both conceptually and empirically, initiating structure is a much broader construct than transactional leadership (while both constructs focus on clarifying tasks and deadlines). Thus, initiating structure dominated transactional leadership in the regression analyses, rendering the latter construct redundant. Redundancy of leadership styles might be responsible for another result: Transformational leadership did not reveal a direct relationship with performance, partially because one of its main components (i.e. individualized consideration) is redundant with consideration. In the regression analyses, both constructs partialled out their respective potential main effects. Interestingly, for future endeavors which aim at integrating various theories of leadership styles, this would imply that at least one

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

component of transformational leadership is redundant, and could thus be neglected, at least when defining a comprehensive set of effective leadership styles. Excluding redundant leadership styles would enhance the level of parsimony; thus, it might be valuable to explore the theoretical overlap between the leadership behaviors of:

. transactional and transformational leadership; and

. consideration and initiating structure.

Implications for practice

In general, the present study highlights the utility of four leadership behaviors. While initiating structure is closely related to performance regardless of the situation, three leadership behaviors depend on certain contextual conditions. That is to say, transformational leadership works best when the work team is heterogeneous with regard to gender. In this situation, leaders could formulate a vision that transcends gender-specific values. Next, if leaders are often absent and thus, “display” laissez-faire behavior, performance still can be high, provided that the work team is heterogeneous with regard to cultural characteristics. Organizations that put high demands on their leaders (e.g. high work load) should enrich their work teams with substitutes for

leadership, such as rules and/or heterogeneous work teams (Podsakoffet al., 1996a).

Finally, besides transformational leadership, considerate behavior is another leadership behavior closely related to performance in heterogeneous (i.e. with regard to gender) work teams. For example, organizations might want to invest in leadership development programs which aim at fostering consideration (Petty and Pryor, 1974) in order to help their leaders to deal with the gender heterogeneity of their respective work teams.

Limitations and directions for future research

The present study was limited to Germany and to public organizations. Thus, future research should replicate the results of the present study in other countries and in other types of organizations. Furthermore, the data of the present study were collected from the same source, leaving room for common-source bias. However, prior research has demonstrated that significant relationships between leadership behaviors and outcome criteria are only somewhat larger in studies that rely on common-source data than

in studies that implement multiple sources of data. (Avolio et al., 1991). Also, the

correlations in Table I revealed that performance was not very strongly correlated with the other constructs. One possible explanation might lie in common-source effects being negligible for the data of the present study.

The cross-sectional study design prevents us from drawing causal inferences. Only longitudinal or experimental studies would allow for causal interpretation of the relationships between leadership behaviors and performance. Thus, future research should implement these kinds of methodological “strong” designs. Another methodological advancement would be the application of multi-level techniques which can account for variance being due to the common department level. For example, it might be possible that several subjects participating were from the same fire department. Thus, their similar responses might be in part due to common work situations (e.g. same supervisor, team size) and might have influenced the results. While the present study relied on a convenience sample where full anonymity was of paramount importance (and thus, no information about the departments was collected), future research should aim at gathering data from the department level.

LODJ

32,6

Although the present study went beyond prior research by including several leadership behaviors, other theoretical approaches to leadership should be included into future studies. As an example, important leadership behaviors such as managerial

control strategies (Gavin et al., 1995) or leadership phenomena such as

leader-member-exchange (Graen and Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden and Graen, 1980) should complement the leadership behaviors which formed the focus of the present study. In the present study, each facet of work team heterogeneity was assessed by a single dichotomous item. This approach represents a simple method for the assessment, and future studies should aim at implementing more sophisticated instruments (e.g. validated surveys with adequate psychometric properties).

As the context factors of work are numerous, the present study is limited by focusing only on one single factor (i.e. heterogeneity of the work team). Practitioners may suspect that heterogeneity interacts with other contextual factors. Thus, the boundary conditions for effective leadership may be much more complex than the model that guided the present study suggested. For example, it has been suggested that the context factors of followers’ skills, task structure, and organizational cycle may well moderate the relationship between leadership behaviors and effectiveness. Considerable more research is needed to explore these context factors. These additional factors were beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, because the present study tested the moderating effect of work teams’ heterogeneity for the first time, the results demonstrate the importance of this single context factor. As such, they are one, – perhaps small, but important step towards a more complex and thus, realistic leadership theory.

References

Antonakis, J. and Hooijberg, R. (2007), “Cascading vision for real commitment”, in Hooijberg, R., Hunt, J.G., Antonakis, J., Boal, K.B. and Lane, N. (Eds),Being There Even When You are Not: Leading through Strategy, Structures, and Systems, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 231-44. Antonakis, J. and House, R.J. (2002), “The full-range leadership theory: the way forward”, in Avolio, B.J. and Yammarino, F.J. (Eds),Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: The Road Ahead, JAI Press, Amsterdam, pp. 3-34.

Antonakis, J., Avolio, B.J. and Sivasubramaniam, N. (2003), “Context and leadership: an examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the multifactor leadership questionnaire”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 14, pp. 261-95.

Avolio, B.J. and Bass, B.M. (1995), “Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: a multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership”,

Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 6, pp. 199-218.

Avolio, B.J., Yammarino, F.J. and Bass, B.M. (1991), “Identifying common method variance with data collected from a single source: an unresolved sticky issue”,Journal of Management, Vol. 17, pp. 571-87.

Awamleh, R. and Gardner, W.L. (1999), “Perceptions of leader charisma and effectiveness: the effects of vision content, delivery, and organizational performance”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10, pp. 345-73.

Bass, B.M. (1985), Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations, The Free Press, New York, NY.

Bass, B.M. (1998),Transformational Leadership: Industrial, Military and Educational Impact, Lawrence-Erlbaum, Mahway, NJ.

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

Bass, B.M. and Steidlmeier, P. (1999), “Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10, pp. 181-217.

Belsey, D.A., Kuh, E. and Welsch, R.E. (1980),Regression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity, Lawrence-Erlbaum, New York, NY.

Bentler, P.M. (2004), “Rites, wrongs, and gold in model testing”,Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 7, pp. 82-91.

Blake, R.R. and Mouton, J. (1964), The Managerial Grid: The Key to Leadership Excellence, Golf Publishing, Houston, TX.

Boone, C., van Olffen, W. and van Witteloostuijn, A. (2005), “Team locus-of-control composition, leadership structure, information acquisition, and financial performance: a business simulation study”,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48, pp. 889-909.

Byrne, B.M. (2001),Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, Lawrence-Erlbaum, New York, NY.

Cheung, G.W. and Rensvold, R.B. (2002), “Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance”,Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 9, pp. 233-55.

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., West, S.G. and Aiken, L.S. (2002),Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Lawrence-Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

Conger, J.A. (2007), “Qualitative research as the cornerstone methodology for understanding leadership”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 9, pp. 107-21.

DiTomaso, N., Cordero, R. and Farris, G.F. (1996), “Effects of group diversity on perceptions of group and self among scientists and engineers”, in Ruderman, M., Hughes-James, M. and Jackson, S. (Eds),Diversity in Work Teams: Selected Research, American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 99-119.

Dumdum, U.R., Lowe, K.B. and Avolio, B.J. (2002), “A meta-analysis of transformational and transactional leadership correlates of effectiveness and satisfaction: an update and extension”, in Avolio, B.J. and Yammarino, F.J. (Eds),Transformational and Charismatic Leadership: the Road Ahead, JAI Press, Amsterdam, pp. 35-66.

Eagly, A.H., Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C. and van Engen, M.L. (2003), “Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: a meta-analysis comparing woman and men”,Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 129, pp. 569-91.

Eisenbeiss, S.A., van Knippenberg, D. and Boerner, S. (2008), “Transformational leadership and team innovation: integrating team climate principles”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 93, pp. 1438-46.

Erdogan, B., Kraimer, M.L. and Liden, R.C. (2004), “Work value congruence and intrinsic career success: the compensatory roles of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support”,Personnel Psychology, Vol. 57, pp. 305-32.

Felfe, J. and Schyns, B. (2005), “Personality and the perception of transformational leadership: the impact of extraversion, neuroticism, personal need for structure, and occupational self-efficacy”,Journal of Applied Social Psychology(in press).

Fiedler, F.E. (1967),A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Fittkau-Garthe, H. and Fittkau, B. (1971),Fragebogen zur Vorgesetzten-Verhaltens-Beschreibung

(FVVB), Hogrefe, Go¨ttingen.

Fleishman, E.A. (1953), “The description of supervisory behaviour”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 37, pp. 1-6.

Fleishman, E.A. (1973), “Twenty years of consideration and structure”, in Fleishman, E.A. and Hunt, J.G. (Eds), Current Developments in the Study of Leadership, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, IL, pp. 1-40.

LODJ

32,6

Frese, M., Beimel, S. and Schoenborn, S. (2003), “Action training for charismatic leadership: two evaluations of studies of a commercial training module on inspirational communication of a vision”,Personnel Psychology, Vol. 56, pp. 671-98.

Gavin, M.B., Green, S.G. and Fairhurst, G.T. (1995), “Managerial control strategies for poor performance over time and the impact on subordinate reactions”,Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 63, pp. 207-21.

Graen, G. and Uhl-Bien, M. (1995), “Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-domain perspective”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 6, pp. 219-47.

Graen, G., Rowold, J. and Heinitz, K. (2010), “Issues in operationalizing and comparing leadership constructs”,Leadership Quarterly, No. 3, pp. 563-75.

Haro, R.P. (1993), “Leadership and diversity: organizational strategies for success”, in Sims, R.R. and Dennehy, R.F. (Eds),Diversity and Differences in Organizations, Quorum Books, London, pp. 78-103.

Harrison, D.A., Price, K.H., Gavin, J.H. and Florey, A.T. (2002), “Time, teams, and task performance: changing effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on group functioning”,

Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45, pp. 1029-45.

Heinitz, K. and Rowold, J. (2007), “Gu¨tekriterien einer deutschen Adaptation des Transformationale Leadership Inventory (TLI) von Podsakoff”, Zeitschrift fu¨ r Arbeits-und Organisationspsychologie, Vol. 51, pp. 1-15.

House, R.J. (1971), “A path-goal theory of leadership effectiveness”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 16, pp. 321-8.

Hu, L.T. and Bentler, P.M. (1999), “Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives”, Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 6, pp. 1-55.

Hunt, J.G. and Conger, J.A. (1999), “From where we sit: an assessment of transformational and charismatic leadership research”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10, pp. 335-43.

Hunter, S.T., Bedell-Avers, K.E. and Mumford, M.D. (2007), “The typical leadership study: assumptions, implications, and potential remedies”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 18, pp. 435-46.

Jehn, K.A., Northcraft, G.B. and Neale, M.A. (1999), “Why differences make a difference: a field study of diversity, conflict, and performance in workgroups”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 44, pp. 741-63.

Judge, T.A. (2005), “Psychological leadership research: the state of the art”, paper presented at the 4th Conference of the German Psychological Association, Section I/O Psychology, Bonn.

Judge, T.A. and Piccolo, R.F. (2004), “Transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic test of their relative validity”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 89, pp. 755-68.

Judge, T.A., Piccolo, R.F. and Ilies, R. (2004), “The forgotten ones? The validity of consideration and initiating structure in leadership research”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 89, pp. 36-51.

Jung, D.I. and Avolio, B.J. (2000), “Opening the black box: an experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership”,Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21, pp. 949-64.

Liden, R.C. and Graen, G.B. (1980), “Generalizability of the vertical dyad linkage model of leadership”,Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 23, pp. 451-65.

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

Looney, S.W. (1995), “How to use tests for univariate normality to assess multivariate normality”,The American Statistician, Vol. 49, p. 64.

Lowe, K.B., Kroeck, K.G. and Sivasubramaniam, N. (1996), “Effectiveness correlates of transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic review of the MLQ literature”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 7, pp. 385-425.

Maurer, T.J. (2001), “Career-relevant learning and development, worker age, and beliefs about self-efficacy for development”,Journal of Management, Vol. 27, pp. 123-40.

Mayo, M., Pastor, J.C. and Meindl, J.R. (1996), “The effects of group heterogeneity on the self-perceived efficacy of group leaders”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 7, pp. 265-84. Petty, M.M. and Pryor, N.M. (1974), “A note on the predictive validity of initiating structure and

consideration in ROTC training”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 59, pp. 383-5. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B. and Bommer, W.H. (1996a), “Meta-analysis of the relationships

between Kerr and Jermier’s substitutes for leadership and employee job attitudes, role perceptions, and performance”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 81, pp. 380-99. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B. and Bommer, W.H. (1996b), “Transformational leader

behaviors and substitutes for leadership as determinants of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship behaviors”,Journal of Management, Vol. 22, pp. 259-98.

Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Moorman, R.H. and Fetter, R. (1990), “Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 1, pp. 107-42.

Polzer, J.P., Milton, L.P. and Swann, W.B. (2002), “Capitalizing on diversity: interpersonal congruence in small work groups”,Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 47, pp. 296-324. Powell, G.N. (1990), “One more time: do female and male managers differ?”, Academy of

Management Executive, Vol. 4, pp. 68-75.

Rohmann, A. and Rowold, J. (2009), “Gender and leadership style: a field-study in different organizational contexts in Germany”,Equal Opportunities International, Vol. 28 No. 7, pp. 545-60.

Rousseau, D.M. and Fried, Y. (2001), “Location, location, location: contextualizing organizational research”,Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22, pp. 1-13.

Rowold, J. and Heinitz, K. (2007), “Transformational and charismatic leadership: assessing the convergent, divergent and criterion validity of the MLQ and the CKS”, Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 18, pp. 121-33.

Rowold, J. and Rohmann, A. (2009), “Definitions of non-profit leadership styles, their effectiveness, and relation to followers’ emotional experience”,Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, Vol. 38, pp. 270-86.

Schruijer, S.G.L. and Vansina, L.S. (2002), “Leader, leadership and leading: from individual characteristics to relating in context”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 23, pp. 869-74.

Shin, S.J. and Zhou, J. (2007), “When is educational specialization heterogeneity related to creativity in research and development teams? Transformational leadership as a moderator”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 92, pp. 1709-21.

Somech, A. (2006), “The effects of leadership style and team process on performance and innovation in functionally heterogeneous teams”, Journal of Management, Vol. 32, pp. 132-57.

Turner, N., Barling, J., Epitropaki, O., Butcher, V. and Milner, C. (2002), “Transformational leadership and moral reasoning”,Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 87, pp. 304-11.

LODJ

32,6

Walumbwa, F.O. and Lawler, J.J. (2003), “Building effective organizations: transformational leadership, collectivist orientation, work-related attitudes and withdrawal behaviors in three emerging economies”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 14, pp. 1083-101.

Walumbwa, F.O., Lawler, J.J. and Avolio, B.J. (2007), “Leadership, individual differences, and work-related attitudes: a cross-culture investigation”,Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 56, pp. 212-30.

Warr, P. and Fay, D. (2001), “Age and personal initiative at work”,European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 10, pp. 343-53.

Xime´nez, C. (2006), “A Monte Carlo study of recovery of weak factor loadings in confirmatory factor analysis”,Structural Equation Modeling, Vol. 13, pp. 587-614.

Yukl, G. (1999), “An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories”,Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 10, pp. 285-305.

Yukl, G. (2002),Leadership in Organizations, 5th ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

About the author

Jens Rowold is a Professor of Human Resource Development, TU Dortmund University, Dortmund, Germany. Jens Rowold can be contacted at: [email protected]

Leadership

behaviors and

performance

647

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail:[email protected]