ORKERS’ RELIGIOUS AFFILIATIONS AND ORGANIZATIONAL

BEHAVIOUR: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY

Seth Ayim Gyekye Mohammad Haybatollahi ABSTRACT

The increased and sustained importance of religion in the workplace has made religiosity an important area of interest in organizational psychology. The current study examined the impact of religion on organizational behaviour among three Ghanaian religious groups: Christianity, Islam, and Traditional African Religion. Workers affiliated with these groups were assessed with standardized research instruments that measured their perceptions of workplace safety, compliance with safety management procedures (safety behaviour), perceived organizational support (POS), job satisfaction, and participation in organizational citizenship behaviours (OCB). Their accident involvement during the past 12 months was also examined. Preliminary analyses with ANOVA indicated that workers affiliated with the Christian faith had the best perspectives on the organizational variables under study. Chi-square and MANOVA revealed that the results were due more to education and socio-economic factors than religious affiliation. After controlling for these confounding effects via multiple regressions, workers of all three religious groups indicated identical scores on the measured items. The results have implications for organizational behaviour and are discussed.

Keywords: Religiosity, educational background, job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behaviour, organizational safety perceptions, perceived organizational support, accident frequency, social exchange theory.

INTRODUCTION

Religiosity and social behaviour

Fem (1963), in An encyclopedia of religion, defines religion to be a set of behaviours or meanings which are connected to the actions of a religious person (p. 647). Religion is such an integral part of life and culture that the essential role it plays in human behaviour has inspired researchers to investigate the potential relationship between various forms of religiosity and social behaviour. This relationship has intrigued both earlier (Allport 1953) and contemporary researchers (Ntalianis & Darr 2005; Lynn et al. 2011). For example, religious commitment and participation have consistently emerged as significant contributors in Quality of Life (QOL) indicators such as life satisfaction, happiness, and meaning in life (Poloma & Pendleton 1990). Poloma and Pendleton’s comprehensive review of the literature indicated that religiosity was an important predictor of general life satisfaction, existential well-being, and overall happiness. Additionally, it has been linked with outcomes including physical health and psychological well-being (Hayward & Elliott 2009), fewer depressive symptoms (Kutcher et al. 2010) and workplace accident frequency (Holcom et al. 1993; Gyekye & Salminen 2007).

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study

Religiosity and organizational behaviour

During the last decade, religious diversity in the workplace has made religiosity an attractive field for organizational research, and has received both theoretical and empirical attention from organizational scholars. According to the literature on psychology of religion, religion produces both formal and informal norms and provides adherents with certain prescribed behaviour (Allport 1953). Several studies that have systematically investigated the underlying dynamics of religiosity in organizational behaviours have found a link between religious affiliation and workplace behaviour. Strong positive correlations have been discovered

between people’s religiosity and their job attitudes (Sikorsa-Simmons 2005; Kutcher et al. 2010), and ethical decision-making in organizations (Weaver & Agle 2002; Fernando & Jackson 2006). Greater religiosity was associated with higher job satisfaction and was a significant predictor of organizational commitment (Sikorsa-Simmons 2005). Fernando and Jackson (2006) suggest that the traditions of the world’s major religions have endured the test of time and note that the values inherent in those religions may be relevant to the management of modern organizations. Most religions and the consequent religious beliefs incorporate strong teachings about appropriate ethical behaviours. These have often guided organizational managers on the moral and ethical guidelines needed in order to resolve ethical dilemmas their organizations faced (Weaver & Agle 2002; Turnipsed 2002). Additionally, religious individuals have indicated higher scores on work centrality, demonstrating that work held a more central role in their lives than their non-religious counterparts (Harpaz 1998). Extant research therefore considers religion as an important mechanism for increased organizational performance, and a spiritually minded workforce as having better work attitudes (Chusmir & Koberg 1988; Lynn et al. 2011).

Work ethic, a religious oriented concept, reflects a constellation of attitudes and beliefs pertaining to work behaviour. Organizational scholars—Kidron (1978) and recently, Sikorska-Simmons (2005)—both found that the Protestant Work Ethic (PWE), measured by the commitment to the values of hard work was positively correlated with organizational commitment and dedication. Organizational commitment reflects being cognitively and

emotionally attached to one’s organization. An individual displaying a high work ethic would place great value on hard work, fairness, personal honesty, accountability, and intrinsic values of work. Contemporary theorists who have examined the PWE have concluded that the PWE is no longer a Protestant issue, as all religious groups espouse the importance of work and, hence, share to the same degree the attributes associated with the work ethic (e.g., Miller et al. 2001; Yousef 2001). For example, the views of Islam about the workplace are denoted under Islamic Work Ethic (ISE), and preach commitment, accountability, and dedication to one’s organization (Yousef 2001). Other religious views like Hinduism and Buddhism also propose hard work and devotion as the tools for the modification and total enrichment of life, the soul and work (Jacobson 1983). For Traditionalists, it is more of teamwork, interdependence, co-responsibility, integrity, and respect for hierarchical order at home and at work (Fisher 1998). Adherents who are committed to their religious ideals have been inspired to show positive work attitudes such as co-operation and loyalty, obedience, commitment and dedication to their organizations (Ntalianis & Raja 2002), exhibited more pro-organizational behaviours (Gyekye & Salminen 2008; Kutcuher et al. 2010) and limited antisocial or counterproductive work behaviour (Ntalianis & Raja 2002).

traffic accidents (Peltzer & Renner 2003), and accident frequency (Gyekye & Salminen 2007; Holcom et al. 1993). According to these reports, workers affiliated with Islam and Traditional African religions, more than their Christian counterparts, tend to be more fatalistic in their causality and responsibility explanations for industrial and traffic accidents, as they emphasized more spiritual influence on the accident process. By contrast, other findings (e.g., Hood et al. 1996; Kumza et al. 1973) did not indicate any association between religious affiliation and organizational behaviours. Kumza and his associates (1973) found that religion was not a significant factor in traffic violations and accidents.

Religious beliefs and values have also been predictive of organizational commitment and job satisfaction (e.g., Veechio 1980). Veechio (1980) found that religious affiliation, after controlling for occupational prestige, accounted for a significant proportion of variance in job satisfaction. Additionally, he noted that religious affiliation was significantly related to organizational commitment, with Protestants displaying higher commitments than Catholics. Membership or affiliation with religious groups provides a mechanism by which individuals establish a highly valued social network (Myers 2000), which is important for the shaping of societal values and norms, and for ethical decision making at the workplace (Weaver & Agle 2002). Allport and Ross (1967) have distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic religious membership. According to these experts, intrinsically oriented persons truly believe in their religious beliefs, internalize them, and use the doctrines to guide them in all other aspects of their life. They view and experience religion as a master motive with all aspects of life referenced to it. In contrast, extrinsically oriented individuals have a utilitarian approach and view religion only as a meaningful source of social status.

Current study and hypothesis

Despite the attention to religiosity and workplace behaviour, this relationship is less clear and ambiguous. The current empirical study is a necessary exploratory study that aims to examine the influence of religion on organizational behaviour in Ghana’s work environment. It investigated workers affiliated with the three main religious groups: Christianity, Islam and Traditional African Religion, and their perceptions and participations in organizational activities. This examination is of relevance due to the great symbolic significance that religious institutions have in Ghana. Official figures released by the Ghana Statistical Services in 2010 put Christians at 65%, Moslems at 20%, Traditionalists at 10%, and people of other or no religions at 5%. Belief in God, Allah, or gods is thus widespread, with many people often deferring to or using theology in their interpretations of social reality. It is therefore not uncommon in Ghanaian workplaces to hear workers cite their religious convictions, among other reasons for behaving in certain ways.

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study

(DeJoy et al. 2010; Gyekye & Salminen 2009). As documented in the literature on psychology of religion, most religions encourage altruistic values and behaviours, and discourage anti-social behaviours. Given the observation that religious doctrines tend to influence considerably devotees’ behaviour (Ntalianis & Raja 2002; Chusmir & Koberg 1988), it is our contention that religious workers’ organizational behaviour will be affected in a positive and constructive way by their relgious tenets. Thus:

Hypothesis: Despite the absence of ample evidence that bears directly on these relationships, it is anticipated that workers of the three religious groups would display positive and identical organizational behaviours.

METHODOLOGY

Participants were 320 Ghanaian industrial workers from underground mines (n = 102) and factories (n = 218). The factory workers were mainly from textiles, breweries, food processing plants and timber and saw-mill plants. Participants had the following characteristics: 65% (n = 208) were male and 35% (n = 112) female. Subordinate workers made up 75% (n = 240) and supervisors 25% (n = 80). Forty-two percent (42%, n = 135) of the participants were married and 58% (n = 185) were unmarried. Christians comprised 66% (n = 211), Muslims, 22% (n = 70), Traditionalists, 9% (n = 29) and workers affiliated with other religious groups such as Buddhism, Shintoism, and Hinduism 3% (n = 10). Their educational background was as follows: 50% (n = 160) had basic education, 30% (n = 96) secondary education, 17% (n = 54) professional education, and 3% (n = 10), university education.

Procedure. During lunch break, participants responded to a questionnaire in English, which took 15–20 minutes to complete. Supervisors were educationally sound and completed the questionnaire unaided. For illiterate or semi-literature respondents who had difficulty understanding written English, the local language was used via the interpretation of a research assistant. All were assured that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential and without disclosure even to their line managers.

Measures

Religious affiliation. Participants were requested to mark the option that corresponded to the religious group to which they belong or adhere. Response options were: (a) Christianity (b) Islam (c) Traditional African Religion and (d) Other.

Religiosity is an indicator of participants’ degree of religiousness. The more value they have for and involve themselves in religious gatherings and activities, the higher their religiosity. It was assessed with a single item measure of frequency of attendance at religious meetings (in church, mosques, and shrines). Response options were: (a) Very Regular (b) Regular (c) Sometimes (d) Seldom (e) Never.

Perceptions of workplace safety were measured with the 50-item Work Safety Scale (WSS) developed by Hayes et al. (1998). This instrument assesses employees’ perceptions on work safety and measures 5 distinct constructs, each with 10 items: (i) job safety (sample item:

(v) satisfaction with safety program (sample item: ‘Effective in reducing injuries’: α = .86). The total coefficient alpha score was .89.

Safety compliance denotes the fundamental and essential activities that employees need to carry out to maintain workplace safety. Items for safety compliance were pooled from the extant literature. Sample items were: ’Follow safety procedures regardless of the situation’: α = .78 and ’Use appropriate tools and equipment’: α = .82.

Accident frequency was measured by participants' responses to the question that asked them to indicate the number of times they have been involved in accidents in the past 12 months. All cases were accidents that had resulted in three or more consecutive days of absence and therefore classified as serious by the safety inspection authorities.

Perceived organizational support refers to the workers’ general perception of their organizations’ contributions and concern for their well-being (Eisenberger et al. 2001). It was measured with the short version of Eisenberger et al’s. (1990) survey of POS. The scale consisted of eight items and assesses workers' evaluations of organizational/management concern for their well-being. Sample items were: ‘The organization values my contribution to its well-being’: α = .79, ‘The organization takes pride in my accomplishments’: α = .88, and

‘Help is available from the organization when l have a problem’: α = .82. Responses to this scale produced a satisfactory reliability of .97.

Organizational citizenship behaviours refer to discretionary behaviours that go beyond those formally prescribed by the organization and for which there are no direct rewards (Organ 1994). OCB was measured with an adapted version of Van Dyne, Graham and Dienesch’s scale (1994). It consisted of 6, 7 and 7 items each on obedience, loyalty and participation respectively. Each of these three categories included items that describe specific behaviour relevant to each category: obedience (sample item: ‘Always on time at work, regardless of circumstances’: α = .76); loyalty (sample item: ‘Volunteers for overtime work when needed’: α = .92, and participation (sample item: ‘Searches for new ideas to improve operations’:α = .92. Total coefficient alpha score was .92.

Job satisfaction denotes the degree at which a worker experiences positive affection towards his/her job. It was measured with Porter and Lawler's (1968) one-item global measure of job satisfaction. This measure was chosen because single-item measures of overall job satisfaction have been considered to be as robust as scale measures (Dolbier et al. 2005; Wanous et al. 1997), and has been used extensively in the organizational behaviour literature (e.g., Nagy 2002; Gyekye 2005; Gyekye & Salminen 2006). Participants responded to all the above scales on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much.

RESULTS

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study

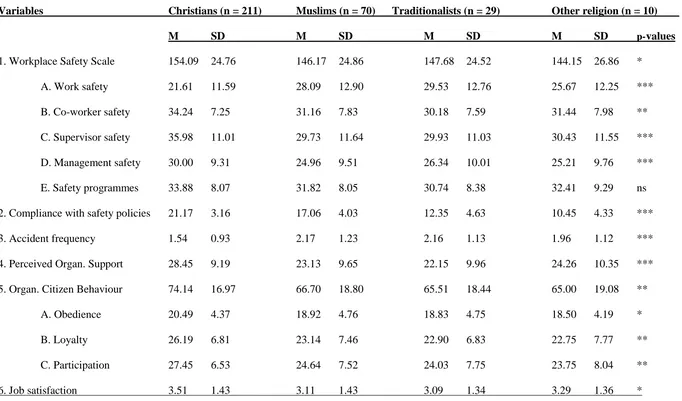

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics on WSS, Compliance with Safe Work Procedures, Accident Frequency, POS, OCB and Job Satisfaction

Variables Christians (n = 211) Muslims (n = 70) Traditionalists (n = 29) Other religion (n = 10)

M SD M SD M SD M SD p-values

1. Workplace Safety Scale 154.09 24.76 146.17 24.86 147.68 24.52 144.15 26.86 *

A. Work safety 21.61 11.59 28.09 12.90 29.53 12.76 25.67 12.25 ***

B. Co-worker safety 34.24 7.25 31.16 7.83 30.18 7.59 31.44 7.98 **

C. Supervisor safety 35.98 11.01 29.73 11.64 29.93 11.03 30.43 11.55 ***

D. Management safety 30.00 9.31 24.96 9.51 26.34 10.01 25.21 9.76 ***

E. Safety programmes 33.88 8.07 31.82 8.05 30.74 8.38 32.41 9.29 ns

2. Compliance with safety policies 21.17 3.16 17.06 4.03 12.35 4.63 10.45 4.33 ***

3. Accident frequency 1.54 0.93 2.17 1.23 2.16 1.13 1.96 1.12 ***

4. Perceived Organ. Support 28.45 9.19 23.13 9.65 22.15 9.96 24.26 10.35 ***

5. Organ. Citizen Behaviour 74.14 16.97 66.70 18.80 65.51 18.44 65.00 19.08 **

A. Obedience 20.49 4.37 18.92 4.76 18.83 4.75 18.50 4.19 *

B. Loyalty 26.19 6.81 23.14 7.46 22.90 6.83 22.75 7.77 **

C. Participation 27.45 6.53 24.64 7.52 24.03 7.75 23.75 8.04 **

6. Job satisfaction 3.51 1.43 3.11 1.43 3.09 1.34 3.29 1.36 *

Accident involvement rate was highest among Muslims and Traditionalists, and lowest among Christians. Christian workers indicated the highest level of organizational support (F(3, 293) = 8.48, p<0.001), and job satisfaction (F(3, 303) = 3.18, p<0.05). They also were the most active regarding citizenship behaviours (F(3, 302) = 5.43, p<0.01), with the highest ratings on obedience (F(3, 302) = 3.57, p<0.05), loyalty (F(3, 303) = 5.31, p<0.01) and participation (F(3, 303) = 5.27, p<0.01). The degree of involvement by Muslims, Traditionalists and those of other religious faiths were identical. The preliminary results designated workers affiliated with Christianity as being more constructive in their organizational performances.

Because educational level and job role have been shown to be confounding variables in previous research (e.g., Status-attainment Models, Blau & Duncun 1967), Chi-square analysis was performed to determine if these variables needed to be controlled. As displayed in Table 2, differences between religious affiliations and education (χ2 = 47.52, df = 9, p<0.001) and

job role (χ2 = 15.76, df = 3, p<0.001) were highly significant. Workers affiliated with the Christian faith were the most educated and, consequently, held more middle- and upper- level managerial positions.

Table 2: Religious affiliation by Job role and Education

Christians Muslims Traditionalists Other religions --- Job role

Supervisors (n = 80) 67% 15% 10% 8%

Subordinates (n = 240) 43% 24% 24% 9%

(χ2 = 15.76, df = 3, p<0.001).

--- Educational background

Basic (n = 160) 35% 33% 25% 7%

Secondary (n = 96) 35% 24% 29% 12%

Professional (n = 54) 71% 12% 9% 8%

University (n = 10) 88% 12% 0% 0%

(χ2 = 47.52, df = 9, p<0.001).

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study

To examine further, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to test the effect of religious affiliations within each educational level and each job role. The interaction effect between education and religion on perceptions of workplace safety was not of statistical significance (F(7, 223) = 1.38, ns), but was highly significant with the inclusion of job role (F(20, 205) = 10.84, p<.001). The effect of religion (F(3, 223) = 3.14, p<0.05) and education (F(3, 223) = 46.46, p<0.001) was statistically significant. Similar observation was made for accident frequency. The interaction effect of religion x education x job role was highly significant (F(20, 261) = 12.96, p<0.001), but not for religion and education (F(7, 223) = 1.38, ns). Meanwhile, the effect of religion (F(3, 282) = 12.10, p<0.001) and education (F(3, 282) = 57.71, p<0.001) indicated differences of statistical significance.

Significant effects were recorded on religion (F(3, 282) = 12.10, p<0.001), education (F(3, 282) = 57.71, p<0.001), and for the three-way religion x education x job role interaction effect (F(20, 256) = 17.83, p<0.001), but not for the religion x education effect (F(7, 223) = 1.38, ns). Assessments regarding worker’s participation in OCB were of statistical significance: the religion x education x job role effect (F(20, 265) = 17.00, p<0.001), religion x education (F(7, 286) = 2.22, p<0.05), religion (F(3, 286) = 9.70, p<0.001), and education (F(3, 286) = 76.00, p<0.001). Ratings on job satisfaction indicated significant effects of religion (F(3, 287) = 4.86, p<0.01), education (F(3, 287) = 47.09, p<0.001), and for the religion x education x job role interaction (F(20, 266) = 10.74, p<0.001), but not for the religion x education interaction effect (F(7, 287) = 1.34, ns). All in all, the results demonstrated the influence of religion, education and job roles on the participants’ behaviours. The effect of educational level and job roles were notably stronger in every measure than that of religion.

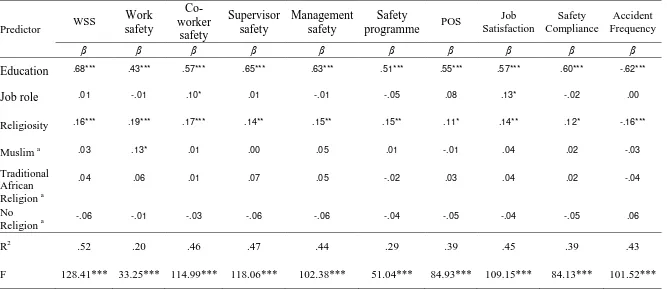

The effect of religiosity was examined via multiple regression analyses. Because religion was multinumial, it was recoded as a dummy variable with Christianity as the reference category. Log transformation was applied to smoothen the distribution of accident frequency, as it was not normally distributed. Multicollinearity statistics did not indicate distortions of results. As reflected in Tables 3a and b, workers’ religiosity and educational background were the most significant variables predicting all components of the orgnaizational behaviours understudy (p<0.001).

Table 3a: Multiple Regression Analyses for Religiosity and Organizational Behavior

Predictor WSS

Work safety

Co-worker

safety

Supervisor safety

Management safety

Safety

programme POS

Job Satisfaction

Safety Compliance

Accident Frequency

β β β β β β β β β β

Education .68*** .43*** .57*** .65*** .63*** .51*** .55*** .57*** .60*** -.62***

Job role .01 -.01 .10* .01 -.01 -.05 .08 .13* -.02 .00

Religiosity .16*** .19*** .17*** .14** .15** .15** .11* .14** .12* -.16***

Muslim a .03 .13* .01 .00 .05 .01 -.01 .04 .02 -.03

Traditional African Religion a

.04 .06 .01 .07 .05 -.02 .03 .04 .02 -.04

No Religion a

-.06 -.01 -.03 -.06 -.06 -.04 -.05 -.04 -.05 .06

R2 .52 .20 .46 .47 .44 .29 .39 .45 .39 .43

F 128.41*** 33.25*** 114.99*** 118.06*** 102.38*** 51.04*** 84.93*** 109.15*** 84.13*** 101.52***

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; values in table are standardized β coefficients.

Notes: a. Christianity is the reference group to which other religious groups are compared. WSS = Workplace Safety Scale (Hayes et al., 1998).

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study

Table 3b: Multiple Regression Analyses for Religiosity and OCB

Predictor OCB Obedience Loyalty Participation

β β β β

Education .64*** .58*** .65*** .59***

Job role -.01 .03 -.02 -.02

Religiosity .16*** .11* .16*** .18***

Muslim a .04 .06 .03 .02

T A R a .05 .08 .05 .02

No Religion a -.05 -.02 -.04 -.06

R2 .45 .36 .46 .39

F 108.80*** 76.18*** 114.84*** 87.13***

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; values in table are standardized β coefficients.

Notes: a. Christianity is the reference group to which other religious groups are compared. OCB = Organizational citizenship behaviors

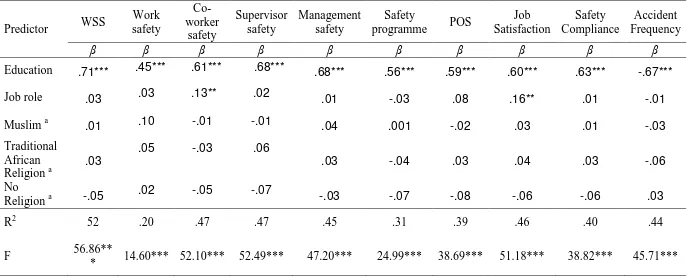

Table 4a: Multiple Regression Analysis for Religious Affiliation and Organizational Behavior while controlling for Education and Job role

Predictor WSS

Work safety

Co-worker

safety

Supervisor safety

Management safety

Safety

programme POS

Job Satisfaction

Safety Compliance

Accident Frequency

β β β β β β β β β β

Education .71*** .45*** .61*** .68*** .68*** .56*** .59*** .60*** .63*** -.67***

Job role .03 .03 .13** .02 .01 -.03 .08 .16** .01 -.01

Muslim a .01 .10 -.01 -.01 .04 .001 -.02 .03 .01 -.03

Traditional African Religion a

.03

.05 -.03 .06

.03 -.04 .03 .04 .03 -.06

No

Religion a -.05

.02 -.05 -.07

-.03 -.07 -.08 -.06 -.06 .03

R2 52 .20 .47 .47 .45 .31 .39 .46 .40 .44

F 56.86**

* 14.60*** 52.10*** 52.49*** 47.20*** 24.99*** 38.69*** 51.18*** 38.82*** 45.71***

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; values in table are standardized β coefficients.

Notes: a. Christianity is the reference group to which other religious groups are compared. WSS = Work Safety Scale (Hayes et al., 1998).

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study

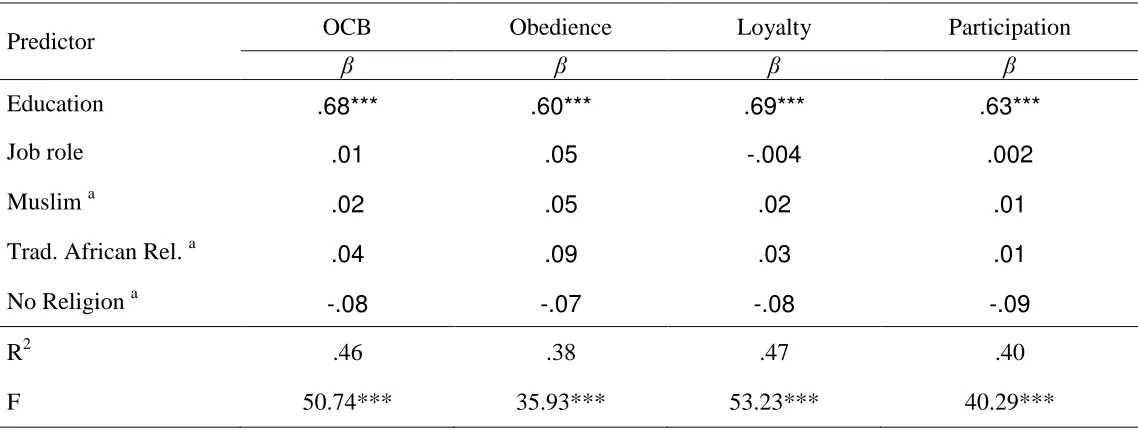

Table 4b: Multiple Regression Analyses for Religious Affiliation and OCB while controlling for Education and Job role

Predictor OCB Obedience Loyalty Participation

β β β β

Education .68*** .60*** .69*** .63***

Job role .01 .05 -.004 .002

Muslim a .02 .05 .02 .01

Trad. African Rel. a .04 .09 .03 .01

No Religion a -.08 -.07 -.08 -.09

R2 .46 .38 .47 .40

F 50.74*** 35.93*** 53.23*** 40.29***

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; values in table are standardized β coefficients.

In the final analyses, the effects of education and job role were controlled and disentagled. As reflected on Tables 4a and b, differences in organizational behaviours between the three religious groups were not of satistical significance.

DISCUSSION

The study explored the organizational behaviour of Ghanaian industrial workers affiliated with Christianity, Islam and Traditional African Religion. As indicated by the preliminary results, workers affiliated with Christianity rated highest on all the scales. They were the most content with the safety levels in their workplaces and recorded the least accident frequency. They expressed the highest level of organizational support, were the most active in citizenship behaviours, and the most satisfied with workplace conditions. These results, which designated workers affiliated with Christianity as being more active in organizational behaviours could be reasonably explained by the fact that most of them were relatively highly educated, occupied prestigious positions as middle management staff, supervisors and unit leaders. They therefore had privileges and access to amenities that were denied their counterparts. These certainly impacted positively on their levels of job satisfaction, and consequently, on other organizational behaviours.

Under such conditions, they had regarded their stress-free job assignments and privileges as some token of organizational support (Eisenberger et al. 2001), and reciprocated1 their organizations by actively participation in citizenship behaviours (Gyekye & Salminen 2005; Eisenberger et al. 2001). Such reciprocals are basically conscious, ethically based acts, specifically done to return appreciation to the employer for providing a satisfying work environment. In contrast, workers affiliated with the other religious groups who were mostly subordinates and relatively less educated, had been assigned heavy workload with little or no privileges, and might have interpreted their predicaments as lack of organizational support. This had led to the observed lower levels of job satisfaction and the subsequent apathy in citizenship behaviours. Additionally, by dent of their educational background, workers affiliated with Christianity had moved to safer jobs as they gained seniority. This had reduced their exposure to risky and hazardous work conditions. This is evidenced particularly by their positive perspectives regarding workplace safety and relatively lower perceptions of inherent danger in their job assignments (Gyekye & Salminen 2005).

Apparently, with the relevant occupational knowledge and expertise, workers affiliated with Christianity had displayed acumen and discretion, recognised situational contingencies, carefully appraised them and avoided disaster. By contrast, their colleagues affiliated with Islam and Traditional African Religion might have been less careful and cautious. Safety reports have confirmed that individuals with Islamic and Traditional African religious backgrounds have displayed fatalistic attitudes (Gyekye 2001) and indulged in higher degrees of risk-taking behaviour (Kouabenan 1998; Peltzer & Renner 2003), which increased their vulnerability in both traffic (Peltzer & Renner 2003) and workplace accidents (Gyekye 2001; Gyekye & Salminen 2007). The contention that the current observation can be explained, at least in part, by educational attainment is reinforced by the close association between religious commitment and higher educational achievement (see review by Jeynes 2001). That Traditionalists and Muslims tend to be relatively less educated than their Christian counterparts has been noted by Ghanaian sociologists

1

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study Takyi & Addai (2002) and succinctly corroborated in the current study. The possibility thus exists that Christian workers were more responsive to the western measures that were used in the analyses. Ghanaian sociologists (e.g., Yirenkyi 2000) 2 have noted the influence which Western religious teachings has had on Ghana's educational system, as most of the reputable educational institutions were established by western religious denominations. The current observation is consistent with previous research reports linking education to job performance. They show that in addition to positively influencing the core task performance, education level is also positively and significantly related to creativity and citizenship behaviours (Ng & Feldman 2009), safety perception and safe work behaviours (Gyekye & Salminen, 2009), and negatively related to counterproductive performance (Ng & Feldman 2009) and accident frequency (Gyekye & Salminen 2009).

Interestingly, the final analyses in which the effects of education and job role were disentangled revealed striking similarity between the work-related values of all three religious groups. The research data indicated a positive relationship between religiosity and organizational behaviour. Adherents, irrespective of religious orientation, who participated actively in their religious activities indicated more pro-organizational behaviours. This positive association has been noted in earlier studies: Holcom and his colleagues (1993) recorded a decrease in workplace accident frequency for workers with high church attendance, and Sikorsa-Simmons (2005) reported a strong association between religiosity and job satisfaction. Apparently, doctrinal issues seem to be the influential factor here, as workers might have been inspired by the moral ethics of their faith. All three religious groups and their consequent religious beliefs incorporate strong teachings about the value of work and appropriate work behaviours. As a result, their followers displayed more pro-organizational behaviours and were less likely to contravene work / pro-organizational ethical behaviours.

The proposition that individuals identifying with religious groups are more likely to live by the values and adhere to the norms of the religious group is a well established argument in the extant literature (Chusmir & Koberg 1988; Milliman et al. 2003; Kutcher et al. 2010). According to the personality and values theory, the identification one makes concerning religious affiliation and or

strength of religious conviction likely becomes part of one’s self-identity and personality (Rokeach 1968). This is more the case when devotees are intrinsically oriented in their beliefs and live the religious doctrines they adhere to (Allport & Ross 1967). It therefore appears to be that participants in the study were principally intrinsically oriented in their religious beliefs and had translated their religious doctrines to their work practices. Since it is generally well-accepted in organizational behaviour theory that personalities and values are critical factors in predicting behaviour in organizations (Kutcher et al. 2010; Chusmir & Koberg 1988), it comes as no surprise that members of all three religious groups displayed equal altruistic values and organizational behaviours when the effects of education and job role were eliminated in the analyses. The current observation is generally consistent with earlier studies that have examined the relationship between religious affiliations and job-related attitudes and found no significant differences between the religious groups studied (e.g., Chusmir & Koberg 1988; Kutcher et al. 2010), and reports that have found

religious doctrines to influence considerably devotees’ social and organizational behaviour (e.g., Allport & Ross 1967; Ntalians & Darr 2005; Lynn et al. 2011).

Safety implications and directions for further studies

The current findings are important from a practical standpoint. The available data reemphasises the vulnerability of Traditionalists and Muslims to industrial and traffic accidents, and the need for

safety programmes specifically designed for them. An integrated approach of education, enforcement and engineering controls will best protect them from accidents and injuries. Secondly, efforts could be directed towards improving the levels at which various workers perceive that they are being supported, appreciated and rewarded by their organizations. The literature on POS is satiated with such organizational structures. Prominent examples are implementing fairness perception measures and showing commitment to workers beyond that which is formally stated in the contractual agreement (e.g., Eisenberger et al. 2001).

The primary strength of the study is its empirical disposition as participants were authentic workplace workers. While these results are encouraging, it is also important to consider that the study is reliant on self-reported instruments. There is therefore the possibility for common method variance among some of the scales. The promise of anonymity and confidentiality would expectedly lower this possibility. Meta-analytic research by Crampton and Wagner (1994) indicates that while this problem continues to be cited regularly, the magnitude of distortions is rather minimal. Self-reported measures have been successfully used in studies on religion (Milliman et al. 2003; Lynn et al. 2011) and safety analyses (e.g., Gyekye & Salminen 2009). The current findings extend previous research by revealing that religious attitudes and practices not only improve job attitudes, but also relate to actual workplace behaviours. It thus contributes to the literature on how religious belief and practice integrate with work. More importanatly, it provides insights into organizational

behaviour of over 95% of Africa’s population. However, generalization of the findings should be done with caution. As this study is among the first attempts to examine the impact of religiosity on organizational behaviours, additional investigations are recommended. Comparative analyses involving workers with and without religious affiliations will be in order and therefore advocated. REFERENCES

Allport, G 1953, The individual and his religion, New York: Macmillan.

Allport, G & Ross, JM 1967, ‘Personal religious orientation and prejudice’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443.

Blau P 1964, Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Blau, P & Duncun, OD, 1967, The American Occupational Structure. Wiley: New York.

Christian, M, Bradley, J, Wallace, J & Burke, M 2009, ‘Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 5, 1103–1127.

Chusmir, HL & Koberg, CS 1988, ‘Religion and attitudes toward work: A new look at an old question’, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 9, 251-262.

Crampton, S & Wagner, J 1994, ‘Percept-percept inflation in micro organizational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 67-76.

DeJoy, DM, Della, J, Vandenberg, R & Wilson, MG 2010, ‘Making work safer: Testing a model of social exchange and safety management’, Journal of Safety Research, 41, 2, 163-171.

Eisenberger, R, Armeli, S, Rexwinkel, B, Lynch, P & Rhodes, L 2001, ‘Reciprocation of perceived organizational support’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 42-51.

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study Fernando, M & Jackson, B 2006, ‘The influence of religion-based workplace spirituality on

business leaders’ decision-making: An inter-faith study’, Journal of Management and Organization, 12, 1, 23-39.

Fisher, R 1998, West African Religious Traditions. Focus on the Akan of Ghana. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gyekye, AS 2001, The self-defensive Attribution Theory revisited: A culture comparative analysis between Finland and Ghana in the workplace, Yliopistopaino, Helsinki, Finland.

Gyekye, AS 2005, ‘Workers’ perceptions of workplace safety and job satisfaction’, International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 11, 3, 291-302.

Gyekye, AS & Salminen, S 2005, ‘Are good soldiers safety conscious? An examination of the relationship between organizational citizenship behaviours (OCB) and perceptions of workplace safety’, Social Behaviour and Personality: An International Journal, 33, (8), 805-820.

Gyekye, AS & Salminen, S 2006, ‘Making sense of industrial accidents: The role of job satisfaction’,Journal of Social Science, 2, 4, 127-134.

Gyekye, AS & Salminen, S 2007, ‘Religious beliefs and workers’ responsibility attributions for industrial accidents’, Journal for the Study of Religion, 20, 1, 73–86.

Gyekye, AS & Salminen, S 2008, ‘Are good citizens religious? Exploring the link between organizational citizenship behaviours (OCB) and religious beliefs’, Journal for the Study of Religion, 21, 2, 85-95.

Gyekye, AS & Salminen, S 2009, ‘Educational status and organizational safety climate: Does educational attainment influence workers’ perceptions of workplace safety?’, Safety Science, 47, 20-28.

Gyekye, AS Salminen, S & Ojajarvi, A 2012, ‘A theoretical model to ascertain detrminates of occupptional accidents among Ghanaian industrial workers’, International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 42, 233-240

Harpaz, I 1998, ‘Cross-national comparison of religious conviction and the meaning of work’, Cross-cultural Research: Journal of Comparative Social Science, 32, 143-170.

Hayes, B, Perander, J, Smecko, T & Trask, J 1998, ‘Measuring perceptions of workplace safety: Development and validation of the work safety scale’, Journal of Safety Research, 29, 3, 145-161. Hayward, RD & Elliott, M 2009, ‘Fitting in with the flock: social attractiveness as a mechanism for well-being in religious groups’, European Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 592-607.

Holcom, M, Wayne, K, Lehman, EK & Simpson, D 1993, ‘Employee accidents: Influences of personal characteristics, job characteristics, and substance use in jobs differing in accident potential’, Journal of Safety Research, 24, 205-221.

Hood, R Jr, Spilka, B, Hunsberger, B & Gorsuch, L 1996, The Psychology of Religion: An

Empirical Approach (2nd edn.). New York: Guilford Press.

Jeynes, H 2001, ‘Religious commitment and adolescent behaviour’, Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 13, 31-50.

Kidron, A 1978, ‘Work values and organizational commitment’, Academy of Management Journal, 21, 239-247.

Kouabenan, D 1998, ‘Beliefs and perceptions of risks and accidents’, Risk Analysis, 18, 243-252. Kutcher, JE, Bragger, JD, Srednicki, RO & Masco, LL 2010, ‘The role of religiosity in stress, job attitudes, and organizational citizenship behaviour’, Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 319-337.

Kumza, J, Dysinger, P, Strutz, P & Abbey, D 1973, ‘Nonfatal accidents in relation to biographical, psychological and religious factors’, Accident Analysis and Prevention, 5, 55-65.

Lynn, ML, Naughton, MJ & Vander Veen, S 2011, ‘Connecting religion and work: Patterns and influences of work-faith integration’,Human Relations, 64, 5, 675-701.

Milliman, J, Czaplewski, JA & Ferguson, J 2003, ‘Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16, 4, 426-447.

Myers, SM 2000, ‘The impact of religious involvement on migration’, Social Forces, 79, 755-783. Nagy, M 2002, ‘Using a single-item approach to measure facets of job satisfaction’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75, 77–86.

Ng, WH & Feldman, DC 2009, ‘How broadly does education contribute to job performance?’, Personnel Psychology, 62, 89-134.

Natlianis, F & Raja U 2002, ‘Influence of religion on citizenship behaviour and whistle-blowing’ in AH Rahin, Golembieski & K Mackenzie (eds.), Current Topics in Management, London: Transaction, pp. 79-98.

Ntalianis, F & Darr W 2005, ‘The influence of religiosity and work status on psychological contracts’, International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 13, 89-102.

Organ, D 1994, ‘Personality and organizational citizenship behaviour’, Journal of Management, 20, 465-478.

Peltzer, K & Renner, W 2003, ‘Superstition, risk-taking and risk perception of accidents among South African taxi drivers’, Accident Analysis and Prevention, 35, 619-623.

Porter L & Lawler, E. III 1968, Managerial Attitudes and Performance, Homewood, IL, USA: Irwin-Dorsey.

Rokeach, M 1968, ‘Beliefs, attitudes and values: A theory of organization and change’, Journal of Social Issues. 24, 1, 13–33.

Sikorska-Simmons, E 2005, ‘Predictors of organizational commitment among staff in assisted living’, The Gerontologist, 45, 2, 196-205.

GA Aymin & M Haybatollahi Workers’ Religious Aaffiliations and Organizational Behaviour: An Exploratory Study Van Dyne, L Graham, J & Dienesch, R 1994, ‘Organizational citizenship behaviour: Construct redefinition, measurement, and validation’, Academy of Management Journal, 37, 765-802.

Vecchio, RP 1980, ‘A test of a moderator of job satisfaction-job quality relationships: The case of religious affiliation’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 195-201.

Wanous, P, Reichers, A & Hody, M 1997, ‘Overall job satisfaction. How good are single-item measures?’,Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 147-252.

Weaver, G & Agle, B 2002, ‘Religiosity and ethical behaviour in organizational: A symbolic integrationist perspective’, Academy of Management Review, 27, 1, 77-97.

Weber, M 1930, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, New York: Scribner.

Yirenkyi, K 2000, ‘The role of Christian churches in national politics: Reflections from laity and clergy in Ghana’, Sociology of Religion, 61, 325-338.