Performance-based Public Management Reforms:

Experience and Emerging Lessons from Service Delivery

Improvement in Indonesia

Derick W. Brinkerhoff and

Anna Wetterberg RTI International

DRAFT: NOT FOR CITATION WITHOUT AUTHORS’ PERMISSION

Paper presented at the panel on

―Public sector reform in developing and transitional countries: What have we learnt and where should we go?‖

International Research Society on Public Management 16th Annual Conference

University of Rome Tor Vergata Rome, Italy

1

From both practical and theoretical perspectives, improved public sector performance has been a major preoccupation of policymakers, managers, and analysts in countries around the world. Performance improvement initiatives have a long history as elements of public sector reform in industrialized countries, and a large literature has examined performance-based reforms, measurement, and management (see, for example, Bouckaert 1992, Kettl et al. 2006). Beyond the industrialized world, such reforms have been promoted by international donor agencies both as remedies for weak public sector performance in developing countries (OECD 2005), and more recently as mechanisms to assure concrete results from development assistance (Savedoff 2011).

Performance-based initiatives are commonly advocated as a remedy for service delivery failures, including weaknesses in service quantity and quality, responsiveness, and

accountability. While there is enthusiasm in many quarters for such initiatives, definitions that clarify their conceptual boundaries are often vague, and the empirical evidence base for their effectiveness is mixed. This paper briefly reviews current thinking regarding service delivery improvement, and identifies several pathways to improved performance. We explore how these performance improvement pathways seek to increase service quantity and quality, raise

2

Diagnosing service provision problems

Political science, public policy, and public administration discourses are replete with diagnoses of public sector service provision problems and recommendations for solving them, far too numerous and diverse to summarize here. All of these discourses are fundamentally concerned with the nature of the relationships among politicians and policymakers, service managers and providers, and citizens and service users. The classic politics-administration dichotomy saw public managers and service providers as faithful translators of policies crafted by politicians into programs and outputs to achieve policy objectives desired by voters. Over a century of academic analysis, normative discussion, and empirical investigation has fed debates on the validity and the reality of the dichotomy as representing an oversimplified and/or mythical vision of public administration (see Svara 2001). According to some, its inherent principal-agent model of mutual high trust led in practice to the rise of the administrative state, bloated

government, and unaccountable public sector employees.

3

Directly targeting service delivery, the World Bank applied the principal-agent

framework to pro-poor service delivery in a widely cited report that elaborates an accountability triangle connecting citizens/clients to politicians and policymakers, politicians/policymakers to service providers, and service providers to citizens/clients (World Bank 2004). The three sides of the accountability triangle represent interlocking and complementary principal-agent relations that constitute a service delivery accountability chain. A direct service delivery chain between citizens/clients and providers, where the former exercise power through transactions and monitoring over the latter, constitutes the short accountability route. When the chain involves state actors—politicians and policymakers respond to citizens/clients’ voice by designing and implementing management and oversight systems to signal and control providers—this is the long route to accountable service delivery. When these chains function effectively,

citizens/clients receive the services they want and need, and both providers and

politicians/policymakers are accountable and responsive. The report offers a review of service delivery experience, exploring each principal-agent relationship, much of which applies NPM approaches and tool.

Current pathways to improved service delivery reflect the legacy of NPM and the predominant impact of the principal-agent perspective on diagnosing performance issues and designing measures to addressing them. Today’s global economic crisis has renewed the drive for public performance improvement and NPM-inspired reforms not just in the developing world, but in industrialized countries as well. Our brief, and of necessity oversimplified, review below highlights how this perspective and the accountability triangle shape pathways to

4

Pathways to improved service delivery

Improved service delivery is the ultimate aim of the various pathways. However, defining what constitutes service-delivery performance and measuring improvements are major

challenges. The dimensions of performance can be roughly divided into two categories: a) features of the outputs of the service-delivery activity, and b) features related to the use of those outputs and to the outcomes achieved. The former include: quantity, quality, cost, efficiency, and effectiveness. The latter include: utilization rates, availability, access, responsiveness,

accountability, and distribution (e.g., equity and poverty-focus), to name the most common. Performance metrics seek to identify appropriate and feasible measures for these performance dimensions, which can vary considerably depending upon the type of service-delivery activity, the difficulty of measurement, the availability of proxies, and the timeframe within which performance assessment takes place (see, for example, Heinrich 2002, Kopczynski and Lombardo 1999). Performance improvement and measurement also need to take account of external factors beyond the control of the particular service-delivery activity (Camm and Stecher 2010). Such factors can be relatively straightforward, such as the availability of funding in a given budget cycle; or they can be more complex and systemic, such as the extent of patronage and elite power in state-society relations.

The pathways discussed here begin with decentralization, a key structural route to service delivery improvement. We next consider pathways that employ mechanisms and procedural tools intended to align the interests of principals and agents to better achieve desired

5

co-production. This latter pathway can include performance-based payment to service users intended to stimulate demand, for example, in the form of vouchers.

Several caveats are in order. First, we make no claim that our list of pathways is exhaustive. Second, real-world applications incorporate multiple pathways. Rarely is there simply a single route to improved service delivery, although international donor assistance may concentrate on one or another pathway more than others. Third, an important question, beyond the scope of this paper, is which combinations of pathways work best and are cost-effective under which circumstances to improve service delivery?

Decentralization

Decentralization is a major pathway to improved service delivery, widely argued to enable performance gains by moving government closer to the people it serves.1 In terms of the principal-agent accountability triangle, decentralization creates additional subnational nodes of state actors, and devolves service delivery to local entities (public, non-profit, or private) thereby shortening the long route to accountability.2

Major analytic streams in the extensive literature focus on how decentralization improves allocative efficiency through matching services with citizen preferences, increases service

production efficiency and cost recovery, and aligns resources with service delivery

responsibilities through various combinations of intergovernmental transfers and own-source revenues (see, for example, the review in Birner and von Braun 2009). Related streams explore decentralization’s impacts on service providers’ incentives for accountability, innovation, and

equitable distribution, and issues of local elite capture and of corruption (e.g., Bardhan and Mookherjee 2000, Crook and Manor 1998, Dillinger 1994).

6

Much analysis has addressed gaps in translating decentralization into practice, and has identified contextual factors that constrain the achievement of decentralization’s theorized benefits in developing countries. For example, Azfar et al. (2001) examined the preference matching argument and found that public officials at the intermediate level (districts in Uganda and provinces in the Philippines) showed no evidence of having better knowledge of the

preferences of local residents, and that local officials at lower levels of government (subcounties in Uganda and municipalities in the Philippines) had only weak knowledge of what citizens wanted. Devarajan et al. (2009) assess the negative effects of what they call ―partial

decentralization‖ on service delivery, where perverse incentives, capacity weaknesses, and

limited accountability are created when central government entities fail to transfer full authorities, responsibilities, and resources to lower levels.

A subset of the decentralization path is granting autonomy to individual service provision facilities. This path has been extensively pursued in health and education, where hospital and school autonomy reforms have devolved responsibility, authority, and revenue generation and expenditure. In some cases, this has meant privatization of public facilities.

Standard-setting

The setting of service-delivery standards, translated into regulations and/or specified in performance contracts, is one route to addressing a common problem with service delivery: lack of clarity regarding the constituent elements of acceptable quality services. Poor quality connects directly to underutilization of services and failure to achieve outcomes. The development of minimum performance standards, or of so-called ―best practice‖ standards (i.e., benchmarking) serves to establish clearer depictions of the elements of performance along with metrics.

7

into administrative and/or legal requirements for service delivery and into specifications for performance contracting. Standards become the metrics that create incentives for agents to improve services (e.g., Rowan 1996).

Studies offer several caveats regarding this pathway to improved services. These include the temptation for agents to select those service recipients most likely to contribute to achieving the standards for which agents are held accountable (―creaming‖), and the difficulty in crafting short-term measurable standards that are reliably associated with desired long-term outcomes (e.g., Heckman et al. 2002). Such problems notwithstanding, in most developing countries standard-setting is a commonly employed route to service delivery improvement, frequently driven by planning and/or monitoring and evaluation systems, many of them donor-supported.

A common standard-setting item in the NPM toolkit is the citizen charter, a frequently employed means of clarifying service delivery expectations and specifying standards. Charters can be developed at various levels; for example, for sectoral ministries and departments, or for individual facilities, such as schools or health clinics. In many developing countries, such charters are posted in the public areas of ministries or facilities, thus contributing to the information-flow and transparency pathway discussed below.

Results-based management

This route to improved service delivery involves public organizational systems and procedures that formally combine target-setting, budgeting that links targets to funding,

8

industrialized countries, results-based management has a long history, beginning with such tools as zero-based and performance-based budgeting, and a variety of legislatively mandated

accountability programs (see Dubnick and Frederickson 2011). NPM-inspired public sector reforms in developing countries have tackled organizational change with the aim of injecting performance-oriented management into the civil service, with mixed results (see Lodge and Kalitowski 2007).

In South Africa, for example, where citizens have been frustrated by poor public service delivery, the Zuma administration created a Ministry of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation in 2009 to respond to the problem. The new ministry established a system that set policy goals and measurable targets for sectoral ministries, and tracked their performance annually against the targets. The targets served as the basis for performance agreements signed between ministers and President Zuma. The terms of the agreements were not required to be made public, though several ministers opted to do so (Friedman 2011).

9

Performance-based payment

NPM led to major attention to contracting as a means to increase performance and accountability and to motivate agents to fulfill the objectives of their principals. This path to service delivery performance improvement has also proven increasingly popular in developing countries, where it has long been used in the infrastructure sectors. For services, donors have supported experimentation with contractual mechanisms that link payment to the achievement of specified service outputs and/or outcomes. These mechanisms are known variously as PBP (performance-based payment), P4P (pay for performance), RBF (results-based financing), among other labels.

PBP seeks to solve the principal-agent problems inherent in service delivery. By creating positive incentives for performance, such schemes can more closely align the interests of agents (service providers) with those of their principals. As Eichler et al. note regarding their use in the health sector, ―performance-based payment establishes indicators of performance that make clear what principals want and give agents financial incentives for achieving defined performance targets‖ (2007, 3). The design of performance verification measures, which trigger the distribution of rewards (monetary and/or other), aims to address the information asymmetry problem.

10

Behind legislation mandates public schools to achieve improvements in student test scores or risk losing federal funding. In the health sector, Rwanda experimented with a District Incentive Fund that rewarded district governments with grants for achieving a combination of increased capacity and service delivery targets (Brinkerhoff et al. 2009). PBP can take the form of performance contracts between public sector entities (sometimes referred to as contracting in), for instance between health financing agencies and facilities (see the examples in Eichler and Levine 2009).

There are numerous examples of PBP mechanisms between the public sector and non-state providers (contracting out) for health, education, infrastructure, and municipal services. The extent to which performance targets constitute contractual elements in PBP mechanisms varies considerably, as does the percentage of contract value placed at risk. Some schemes with local NGO providers use bonus payments on top of a base level of grant funding, with pay-outs triggered according to phased achievement of targets (see Eldridge and Palmer 2008, Eichler and Levine 2009).

Arrangements for monitoring and verification of the achievement of performance targets vary as well. Public audit agencies, contracting out to private audit entities, internal review units, legislative review committees, professional associations and boards, citizen/community and NGO monitors are all common means of tracking and verifying performance. These are often found in combination. In principal-agent terms, they all share the common challenge of seeking sufficient information from agents to assure that the intended performance that principals want to achieve is realized. Without reliable and accurate verification of performance, the

11

Information flows and transparency

The availability and dissemination of information regarding policies, programs, resource allocations, and results relative to services are the core elements of another pathway to improved service delivery. The good governance agenda prioritizes information flows and transparency as hallmarks of increased accountability and improved governance (Brinkerhoff 2005). In terms of governance, the state’s legal and institutional structures play a role both in creating and

supporting this pathway. These include laws and procedures that make information available and transparent, such as freedom of information acts (FOIAs), so-called sunshine legislation that mandates government to disseminate budget and program documents, and procedural

requirements for open hearings on matters of concern to citizens.

In terms of improved service delivery, expanded information flows address first the technical dimensions of service delivery by generating the data and knowledge on need, demand, quantity, quality, distribution, and outcomes and impacts required by policymakers, program designers, and service providers. This pathway contributes to better service forecasting, resource allocation, and utilization through mechanisms such as management information systems, results reporting frameworks, and/or participatory planning and budgeting exercises. When applied to service users, the provision of information, for example through targeted social marketing and communication campaigns, can enhance service uptake and utilization rates.

Second, this pathway addresses the information asymmetry problem in principal-agent interactions, which enables increased accountability and better incentives on the part of providers. Expanded information availability and dissemination feed into performance

12

governments hold Open House and Accountability days (Journées des Portes Ouvertes), where local officials provide information to citizens, and citizens have a regular opportunity to question them and become informed about district development plans and sectoral services (Brinkerhoff et al. 2009). Information availability and dissemination are key to giving effect to the citizen participation pathway.

Citizen participation

This pathway concentrates on the demand-side of service delivery, incorporating voice and demand aggregation (citizen satisfaction surveys), empowerment and collective action (citizen/community monitoring), market power (e.g., vouchers), and service co-production. Among the best-known examples is Tendler’s (1997) widely cited study of participatory health service delivery in the Brazilian state of Ceará, where state health officials set and enforced the standards for hiring and performance of community health workers (which avoided clientelism in hiring), while establishing local structures and procedures that engaged local health service users as active participants in assessing health worker performance. However, citizens’ ability to judge performance can limit their contribution to motivating service providers. For example, Banerjee et al. (2006), in a study in India, find that parents’ ability to assess the educational achievements of their children was low.

13

shown, however, that perceptions of service quality are influenced by a range of factors,

including the overall quality of governance, prior expectations, how equitably services are made available, and the type of service evaluated (Deichmann & Lall 2007, Van Ryzin 2007).

The extent to which citizens perceive their local governments to be transparent and responsive to their needs can significantly influence their views on service delivery. In their analysis of citizen responses to dissatisfaction, Lyons and Lowery (1989) show that service-users’ with low levels of political efficacy – defined as feeling that one can influence government and have officials care about one’s opinions – are significantly more likely to respond to unsatisfactory services by disengaging with government (―neglect‖ in their model), rather than actively expressing their dissatisfaction.

Another intervening factor is citizens’ prior experiences with services. Through expectancy confirmation, the degree to which current outcomes exceed or fall short of those expectations has been shown to influence current satisfaction (James 2009, Van Ryzin 2007). If current service delivery exceeds expectations (positive disconfirmation), citizens’ satisfaction

will be higher than if the same objective quality were delivered in a context with raised

expectations. A study looking at satisfaction with services and trust in government in Iraq noted the effects of citizens’ expectations, based on prior service experience, on satisfaction levels with current services (Brinkerhoff et al. 2012).

Finally, the correlation between users’ satisfaction and objective service quality has been

14

2007). In a study in India, Deichmann and Lall (2007) demonstrate that a generally positive relationship holds between household satisfaction with water service and daily duration of water availability in Bangalore. Israel (1987) offers an explanation of which services are more likely to be accurately judged by users: those that have high degrees of specificity. He defines

specificity in terms of ―the degree to which it is possible to specify the objectives of a particular

[service delivery] activity, the methods for achieving them, and the ways of controlling achievement‖ (1987, 48) along with the extent to which the results of the activity have immediate, identifiable, and targeted effects on service users.

The use of community empowerment mechanisms is a well-recognized means to align service delivery to local needs and preferences. Parents’ associations, health committees, and community-based natural resources management arrangements bring communities into partnership with public providers precisely for the purpose of assuring that services meet user needs. The literature on state-society synergies for co-production of services highlights this outcome, as well as the benefits for efficiency and effectiveness (see, for example, Evans 1996). The empowerment aspect of these co-production partnerships emerges most strongly when the information provision on needs and preferences that feeds into alignment is joined with oversight and accountability.

For example, in the Philippines, a demonstration project on the island of Mindanao established Quality Assurance Partnership Committees in local health facilities explicitly to serve both service quality assurance and citizen empowerment functions (Brinkerhoff 2011). On the service side, the QAPCs offered facilities feedback on client satisfaction. On the

15

QAPCs sought to provide review and problem-solving to identify actions to improve facility services.

Such empowerment mechanisms, in the ideal, lead service providers to pay attention to performance. They serve as sources of demand and capacity not just for efficient service

provision but also for performance that is accountable and responsive. Several constraints limit whether citizens can, in practice, fulfill these functions. First is technical expertise; particularly in situations where engaging with service providers calls for technical competence, citizens may face information asymmetries and knowledge barriers. Second, there is some degree of role conflict between citizens as co-producers of services in partnership with providers and as accountability monitors.

Summary

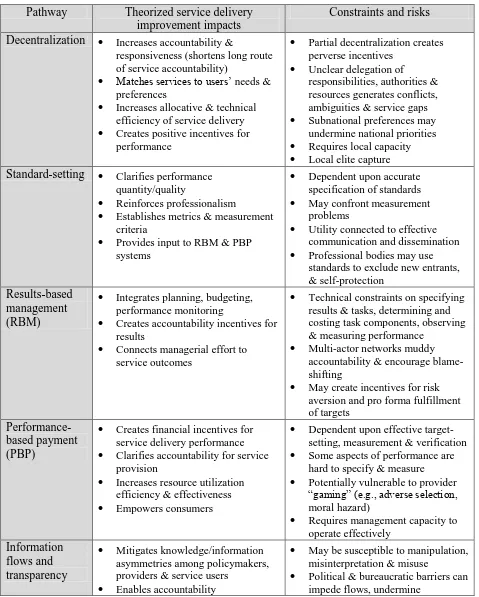

Our rapid review of pathways to improved service delivery has demonstrated the

hypothesized benefits of each pathway, noted the major constraints and limitations they face, and provided some country examples. Table 1 offers a summary. The discussion also revealed the connections among the pathways. The decentralization pathway shapes in many cases the institutional and structural landscape upon which other pathways are pursued. Similarly,

information flows and transparency support the other pathways, as well as constituting a reform route that is often taken up by reformers in its own right. We now turn to an exploration of Indonesia’s experience with these pathways.

INSERT TABLE 1 HERE

Pathways experience in Indonesia

16

groups and civil society organizations, Indonesia entered a transition period of intense reform (referred to as the era of reformasi ). The first two post-Suharto administrations, the Habibie and Wahid governments, loosened controls on the press, paved the way for independence in East Timor, initiated an ambitious program of decentralization, established special autonomy packages for Aceh and Papua, began reforming the electoral system, and took important first steps to reduce the role of the military in politics and the economy. Free and fair general elections were held in 1999 and 2004. Reforms continued, though at a slower pace, under the Sukarnoputri government (2001-2004), and subsequently under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who won a decisive electoral victory in 2004, and was re-elected in 2009.

The international donor community mobilized to support Indonesia’s transition to democracy and good governance. Public sector reform programs aimed to support the country’s ambitious decentralization program, increase administrative efficiency and effectiveness, and reorient the public administration toward responsiveness to its citizens. Numerous initiatives targeted performance improvement in key sectors, such as health and education. The following discussion reviews a selected set of these reforms.

Decentralization

Indonesia embarked on a rapid decentralization program beginning in 1999. Through a series of reforms, the bulk of authority for fiscal and legislative decisions, as well as service delivery, were transferred to the district level.3 Decentralization has had a significant impact on subnational public expenditure. The World Bank (2006) estimates that 40 percent of public

3 Subnational administrative levels of government in Indonesia include the propinsi (province), kabupaten/kota

(regency/municipality, both considered districts), and desa (village). Since 2004, the kecamatan (sub-district) has been subsumed under the kabupaten, but this level retains important functions in some of the country’s largest development programs, including the Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Masyarkat (PNPM, National Community

Empowerment Program) discussed below. See Rapp et al. (2006) for a comprehensive review of Indonesia’s

17

spending is currently the responsibility of subnational governments. As the majority of these resources come from central transfers, the efficiency and effectiveness of the intergovernmental transfer system are critical. While the central government has retained the potential to use budget transfers as incentives for performance, these possible channels for influencing the quality and orientation of service delivery at more local levels have not been used effectively (Buehler 2011,

Ferrazzi 2005, Lewis & Smoke 2011).

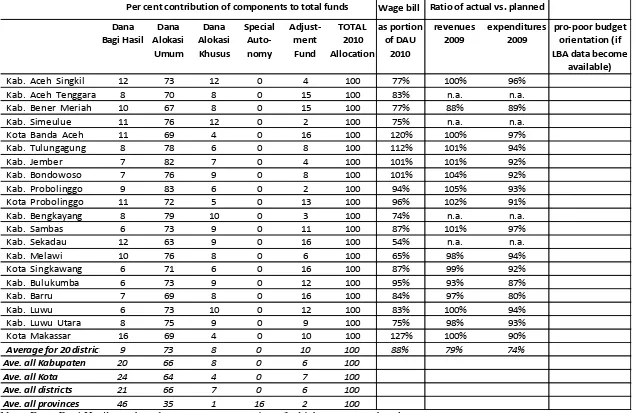

Fiscal incentives are weak, and their effectiveness is not maximized by national

policymakers. For example, general revenue allocations (Dana Alokasi Umum orDAU) cover over a third of provincial budgets and two thirds of district budgets, on average, and even larger proportions in some districts, as Table 2 shows. The size of the DAU is partly determined using a fiscal equalization formula and partly calculated to cover the subnational wage bill, without taking into account past years’ utilization or existing reserves. In spite of surpluses in many

districts, the central government has refrained from varying DAU allocations to encourage districts to invest in service improvements (Lewis & Smoke 2011). The central government’s coverage of the district wage bill4 also discourages districts from experimenting with different models of service delivery, as overhauling staffing patterns and streamlining wage structures would produce no gains to district budgets (Heywood & Choi 2010). The smaller specific purpose grants (Dana Alokasi Khusus, or DAK) have been structured to include a matching grant to encourage capital investment, but these funds have been shown to crowd out capital spending from other sources, diluting their effect (Lewis and Smoke 2011).

INSERT TABLE 2 HERE

Further, the central government has not provided reliable information on the amounts and timing of transfers. A recent study in Aceh (Morgan et al. 2012), confirmed that district

18

governments are not always aware of the amounts of central and provincial transfers they can count on receiving, and during a given fiscal year, transfers are often delayed (World Bank 2006).

Because the central government imposes few controls on intergovernmental transfers, local officials have wide leeway to decide on spending targets. In health, local discretion on spending targets has resulted in some degree of sub-optimal resource allocation in terms of health priorities. Spending does not always target the health needs of the poor, and local parliamentarians have in some cases favored investment in visible infrastructure in support of increased curative care rather than in prevention (Heywood & Choi 2010). In Aceh, such spending patterns are reinforced by the power of well-off former members of the armed

resistance movement (GAM) who head construction firms to influence budgeting votes in local parliaments, as well as by the desire of local politicians to be associated with visible results of their budgeting decisions (Morgan et al. 2012).

19

Standard-setting

The Indonesian legal framework for decentralization incorporates minimum service standards (MSS). A year after the launch of its aggressive decentralization program in 1999, the central government introduced MSS for nine sectors: public works, health, education and culture, agriculture, industry and trade, investment, environmental affairs, land affairs, cooperatives and labor affairs. Because the MSS were ill-defined and complex, and the roles of central and local agencies in their implementation conflicted, however, they were often ignored by district service providers who found them overwhelming and confusing (Ferrazzi 2005,

World Bank 2008, 2010).

In spite of subsequent laws to clarify content and implementation (Law 32/2004 and Government Regulation 65/2005) and to enhance the role of citizens in holding service providers accountable (Law 25/2009), meeting MSS remains a challenge for service providers. Some of the obstacles are linked to budget planning processes, which remain divorced from MSS (APiH 2008). For political reasons, the central government has also refrained from directing portions of the DAU to meeting MSS, as the general purpose block grant has become popular with districts (Ferrazzi 2005). Because of the poor definition of standards, districts rarely apply them as local budget or program criteria. It is also unclear how progress on MSS is monitored, and what incentives subnational governments have to implement them (Lewis and Smoke 2011). A review of Indonesia’s progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 (reducing child

mortality) and 5 (improving maternal health), found that ―the shortcomings of the health

20

requirements (Morgan et al. 2012), and higher-level offices have little information on where the bottlenecks lie.

In the education sector, recent efforts have aimed to improve providers’ understanding of

MSS and the real costs of achieving them. After new standards were approved in 2010, the Ministry of National Education calculated aggregate costs of achieving standards, but did not break costs down for individual districts. Efforts are underway to help district officials calculate the locally relevant cost to meet standards. A tool entitled, Calculation of Costs to Achieve Minimum Service Standards and Universal Access (Penghitungan Biaya Pencapaian Standar dan Akses Pendidikan, or PBPSAP), relies on data collected through the ministry’s management information system. It provides analysis and guidance for local governments to determine policy alternatives to meet standards and targets most efficiently. By September 2011, the PBPSAP had been applied in 26 districts (RTI International 2011a).

Results-based management

In Indonesia, the results-based management pathway has been pursued on several fronts. Performance-based budgeting regulations for subnational governments were instituted in 2000 and 2002 to improve the links between planning, budgeting and levels of services (ADB 2004, 78). The results orientation is also reflected in efforts to improve accountability and transparency of DAK funds by subdistricts. By shifting the central government’s orientation from financing inputs to reimbursing for independently verified outputs, the World Bank’s Local Government

21

are tied to completion of outputs verified by the State Finance and Development Auditing Agency (Badan Pengawasan Keuangan dan Pembangunan, BPKP) (Ellis et al. 2011).

As the project has been operational only since January 2011, the results of the first verification are not expected until April 2012. A critical element of the project is BPKP’s independent verification, given the ubiquitous weak information systems that present challenges to all pathways for improving service delivery and enhancing accountability of local

governments. Project data also indicate, however, that substantial bottlenecks persist in the accountability of central agencies for providing promised funding. While 63 of 78 participating

kabupaten had passed budgets on time (by Feb. 28, 2011) to ensure receipt of DAK transfers by March 31, only 44 of the participating districts received transfers by this deadline (World Bank 2011).

Performance-based payment

In Indonesia, several experiments with performance-based payment schemes have focused on the health sector. From 2000 to 2003, the Ministry of Health, the National Family Planning Coordination Board (BKKBN), and the World Bank collaborated on a pilot program in Central and East Java that gave poor women vouchers to encourage visits to private village midwives for maternal and child health, and family planning services. Although a full and rigorous evaluation was not feasible for the pilot, the available evidence indicated that 74% of poor women in Central and East Java who received the vouchers (in 2000) used them for skilled deliveries, compared to 26.1% of poor women who had skilled deliveries at baseline (December 1999) in Central Java (World Bank 2005, 5-6). The increased demand expressed through poor women’s use of vouchers doubled the number of midwives in the pilot districts, with midwife

22

During its short implementation period, the voucher pilot demonstrated ―that demand -side incentive payment mechanisms using government funding‖ are a logistically feasible way to improve service delivery to the poor in Indonesia (World Bank 2005, 12, 15).5 However, the pilot also highlighted the challenges of sustaining performance-based payment, given weak district-level capacity for implementation and weak support at the provincial level (Brenzel et al.

2009). The pilot also raised concerns that the increased demand could exceed health system capacity, resulting in overcrowded hospital delivery facilities (Gorter et al. 2003).

A more recent performance-based financing experiment was carried out by the Dutch non-governmental organization, CORDAID, which has implemented similar programs in

Rwanda (Soeters et al. 2006). Working in two remote, predominantly poor districts on the island of Flores, the project collaborated with provincial, district, and local health officials (as well as with a Jakarta-based private firm) to identify a series of service quantity and quality indicators (Schoffelen et al. 2011). Starting in 2009, local health facilities and district hospitals were given financial rewards for increases in the number of new consultations, referrals, complete

immunizations, new and cured TB cases, safe deliveries, and treatment of low birth weights, among other quantity indicators (fifteen for health facilities, eleven for district hospitals). Quantity indicators were verified monthly, through inspections of a sample of health facility records, and visits to patients to verify that treatment had taken place. Quality was gauged quarterly, using an extensive list of indicators of hygiene and sanitation, regular consultation, emergency service, delivery care, etc.

As of August 2010, project records showed that the number of patients accessing medical services had increased in both districts. Compared to a June 2009 baseline survey, quality

23

indicators in the project districts had increased by an average of 18%, compared to 1% in a neighboring control district (Schoffelen et al. 2011). Although these results are impressive, it should be noted that inspections of both quantity and quality were carried out by teams trained and funded by CORDAID. Concerns about sustaining the performance-based incentives, given a prior lack of record-keeping and supervision by district and provincial health authorities

(Schoffelen et al. 2011) are thus similar to those for the voucher pilot implemented through the Safe Motherhood project.

Information flows and transparency

Over the past decade, significant advances have been made in information transparency and dissemination as a means of improving service delivery, particularly in combination with citizen participation. While these achievements have often been limited to specific jurisdictions, rather than changes across Indonesia, their importance should not be discounted in a context where, until very recently, citizens had no information on, or say in, how services were delivered and budgets spent (see, among others, Hopkins & Nachuk 2006, MacLaren et al. 2011, RTI International 2009).

One prominent development has been the emerging budget analysis movement in Indonesia, led by Sekretariat Nasional Forum Indonesia Untuk Transparansi Anggaran

(National Secretariat of the Indonesian Forum for Budget Transparency, abbreviated SekNas FITRA). Since 2000, SekNas FITRA and its civil society and donor partners have worked to analyze budget allocations, availability of budget information, and, in some cases,

24

complemented these efforts with collection of a range of indicators of the quality of district governance (including indicators for accountability, participation, gender equality, and

transparency). This work has garnered widespread support6 and has been used as input to citizen prioritization of budgets, benchmarking for district governments and as baselines for service delivery interventions.7

Notably, it is not only citizens that require more information on the funding and

administrative arrangements for service delivery. After decentralization, the level of funding for education increased at the district and school levels. However, local education officials did not know what resources they could expect to receive as the information on transfers was dispersed across a range of sectoral budgets and financing mechanisms, making planning difficult. To make the decentralization of funds effective, local officials needed financial analysis tools to clarify available resources. For instance, USAID’s Decentralized Basic Education program’s District Education Financial Analysis (Analisa Keuangan Pendidikan Kabupaten/Kota, or AKPK) condenses and reworks information from various government budget documents into a transparent picture of where funding comes from and on what the money is spent. The analysis helps to inform decision-making, set priorities among district development sectors and within the education sector, and assess fairness of funding allocations (through per-student expenditure by level of education). The information can also be applied to compare performance among districts, match expenditures to key performance indicators, link results to inputs, and

disseminate clear information for use in public policy debate. AKPK has been used in more

6

See

http://www.seknasfitra.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=76&Itemid=151&lan g=in for a current listing of projects and sponsors.

25

than 70 districts and has been transferred by USAID to other education projects (RTI International 2010a).

Citizen participation

Involving citizens in service improvements can take many forms. One way is to invite users to assess services through satisfaction surveys and citizen report cards, but as noted above satisfaction ratings can have tenuous relationships with objective indicators of service delivery, as user satisfaction may be colored by a range of factors. In Indonesia, the correlation between indicators of facility quality and satisfaction has been found to vary across services and is much weaker for public schools than for public health facilities (Dasgupta et al. 2009, 27). In line with these findings, Lewis and Pattinasarany (2008) find that objective indicators are significant predictors of satisfaction with education in 89 districts, but that their overall contribution is small relative to governance and control variables.8 In particular, transparency in local budget matters and school administrations’ responsiveness to stated problems significantly improved

satisfaction, while awareness of corruption in the school administration reduced satisfaction (p. 16). Though objective indicators (such as student-teacher ratios and classroom conditions) were also important to users’ perceptions, satisfaction was clearly colored by more general

experiences with local government.

Rather than asking only about satisfaction, surveys that ask citizens to identify bottlenecks in service provision have been used to identify locally relevant areas for

improvements and benchmark provider performance. Antlöv and Wetterberg (2011) recount use of such a survey in Gowa, South Sulawesi where the reform-minded mayor took up the results of the 2008 survey to resolve problems with health service delivery and repeated the survey in

8 Both Dasgupta et al. (2009) and Lewis and Pattinasarany (2008) rely on the same data set (Governance and

26

subsequent years to measure progress against the established benchmarks. As Deichmann and Lall (2007) note, setting such benchmarks can substantially improve the utility of satisfaction surveys. However, the effectiveness of citizen-determined benchmarks is crucially reliant on the willingness of local officials to use them to monitor and improve service quality.

Going beyond the intermittent surveys of user service assessments, one government program, supported by the World Bank, involves communities directly in monitoring standards (transparency) and rewards them for improvements in health and education indicators (results-based management): PNPM Generasi (Program Nasional Pemberdayaan Masyarkat - Generasi Sehat dan Cerdas, or National Community Empowerment Program – Healthy and Smart

Generation). PNPM Generasi is oriented around twelve indicators of maternal and child health9, as well as educational behavior.10 The indicators were chosen because they were directly within the community’s control, but also corresponded to stated national priorities. In the multi-year program, communities are given first-year block grants that they can use for any purpose to improve these indicators. To select interventions, they identify problems and bottlenecks and consult with program facilitators, health and education service providers for information, technical assistance, and coordination between villages for shared services and investments. In subsequent years, villagers are awarded additional funding if they show performance

improvements on the twelve specified indicators.11

An evaluation has shown that performance incentives in the form of community block grants can drive improvements in health service provision. Comparing performance with a ―non-incentivized‖ control group revealed that performance-based incentives led to statistically

9 Four prenatal care visits, iron tablets during pregnancy, professionally assisted delivery, two postnatal care visits,

complete childhood immunizations, monthly weight increases for infants, weight checks for children under five, biannual vitamin A pills for children under five.

27

significant, improved outcomes on the eight health indicators. Encouragingly, performance improvements were larger in villages with low baselines for service delivery (Olken et al. 2011).

Many performance-based incentive programs reward providers directly for reaching targets, and some rely on consumers to provide feedback on quality (often through satisfaction surveys) (Meessen et al. 2011). Given the weaknesses of district financing mechanisms and information systems, and the numerous influences on user satisfaction reports, the standard model is unlikely to work effectively in Indonesia. PNPM Generasi circumvents these obstacles by holding neither providers nor individual households’ (and their reports of service quality) responsible for driving performance improvements. Instead, the program relies on villagers collectively, represented by an eleven-member team and village facilitators, to work with

providers to improve delivery. Accountability is thus enforced through two sets of relationships. First, the community holds providers to account for providing additional services that improve the selected indicators. Second, the PNPM program holds the community accountable for improvements, by only rewarding communities that show enhanced outcomes.

In spite of the program’s demonstrated effectiveness, it is not a model that can

necessarily be applied more generally as it is unlikely to work for all services. In fact, the PNPM Generasi evaluation showed no effect on the selected education indicators (Olken et al. 2011). The specific allocations of responsibility for performance improvements set up for PNPM Generasi proved effective for improving selected health service targets, but the distinct

institutional constellations and output/outcome characteristics of other services will likely require different arrangements.

28

village councils, and also in combination with democratic election of committees.12 These authors posit that linkages improve outcomes by raising village leaders’ and community

members’ awareness of the school committee and engagement with students by ―engender[ing]

respect for the school committee in the eyes of the teachers, increas[ing] time household

members help their children with homework, and prompt[ing] greater effort by teachers, largely spent outside the classroom‖(Pradhan et al. 2011, 4).

At the co-production end of the participation pathway’s spectrum, school committees that incorporate parents and other community members are one avenue for citizens to directly

contribute to the production of improved educational services. Although the roles and

responsibilities of school committees were set out in a 2002 decree,13 these bodies have not taken on the envisioned tasks of supporting, monitoring, advising, and mediating in schools, instead only signing off on school officials’ decisions. One component of the Decentralized Basic

Education Project (DBE1) was to strengthen school committee involvement in planning and management, with a long-term goal of improving educational outcomes. After school committee training through DBE1, the proportion of school committee members reporting that they were ―active‖ in preparing and implementing school development plans rose to 84% by the end of the

project in July 2008 (compared to 13% on average at baseline in December 2005) (Heyward et al. 2011, 8).14 At the same time as school committees became more active, financial information was shared much more frequently; over 50% of schools disseminated financial reports in two or

12

In contrast, neither grants to, nor training for, school committees improved learning outcomes.

13 Keputusan Menteri Pendidikan Nasional (Decree of minister for national education) No. 044/8/2002)

14 Level of activity was evaluated based on participation in planning, community consultation, collating information,

29

more venues and the quality of school development plans improved (RTI International 2010b, 26).15

As part of this process of engaging the school committees, community funding for school activities increased substantially, from Rp 6.7 trillion in 2006/07 to Rp 8 trillion in 2008/09 at DBE1 Cohort 2 schools. As community members became more aware of planned school activities and the limited financial resources available, they contributed monetary and in-kind support for service delivery by schools (RTI International 2010b, 51). In this way, citizens not only participated in planning school programs and monitoring their performance, but directly supported production of education services.

As these programs demonstrate, linking the pathways for citizen participation with transparency through community monitoring (sometimes of specific standards) can improve service delivery. However, the mechanisms chosen for specific forms of service delivery matter greatly for effectiveness. Another concern is about sustainability of improvements. For example, in the DBE1 project, analysis revealed that as school committee activities declined in intensity, so did school officials’ efforts at transparency. However, the quality of school development plans has been consistently high over the life of the project, which provides some encouragement that introduced patterns of behavior may persist.

Addressing performance improvement: the Kinerja project

Donor partners continue to work with Indonesian counterparts at both national and subnational levels to pursue the pathways to improved service delivery discussed above.1615 In 2005, 2% of schools had development plans that met quality expectations. By 2008, 98% of schools met these

criteria (RTI International 2010b, 24).

16These include USAID’s Strengthening Integrity & Accountability Program II, AusAID’s Indonesia

-Australia

30

Among the recent donor-funded projects to focus directly on service delivery performance is the USAID-funded Kinerja project, the latest in a long series of USAID projects that have supported local government and decentralization (see RTI International 2009). Currently in its second year, Kinerja works in 20 districts (both kota and kabupaten) in four provinces (Aceh, East Java, South Sulawesi, and West Kalimantan) to ―solidify the links between stimulation of demand for

good services through active civil society engagement and improved local government response‖

(RTI International 2010c, 2). The executive in each district (mayor/walikota or regent/bupati) leads a consultative process to select a set of services to target for improvement. Service options included health, education, and local economic development, as these are the most commonly identified for improvement by Indonesian citizens (RTI International 2011b).

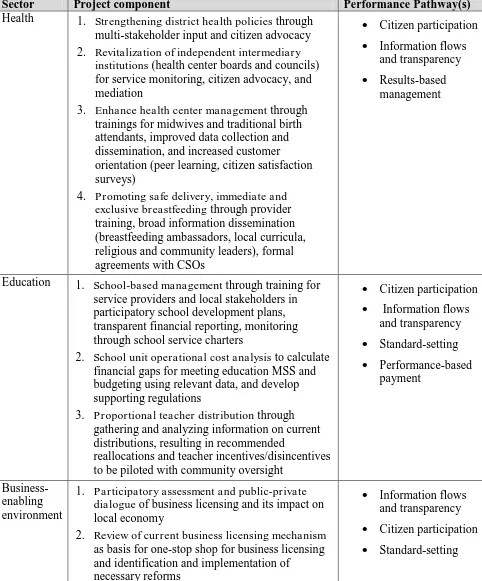

Within each sector, the project works with local governments, civil society, and service providers on specific interventions, chosen for their alignment with national policy priorities and/or demonstrated effectiveness. Kinerja also includes a series of cross-sectoral interventions designed to create incentives for improved local service delivery performance, by giving citizens a more effective voice in public service delivery, supporting performance management systems in local governments, and increasing competition, through benchmarking, competitive awards, and public information (RTI International 2011b).

As summarized in Table 3, Kinerja interventions focus on a selection of the pathways to improved service delivery. The majority of interventions combine citizen participation,

information transparency and dissemination, with a subset also emphasizing standard-setting and results-based management. The selection of pathways reflects the institutional orientation of the project, with its focus on interactions between district government, citizens, and service

31

INSERT TABLE 3 HERE

One of the project’s challenges, however, is to work with district governments of varying

capacity and interest in improving service delivery. All projects face this hurdle, but it is exacerbated by Kinerja’s design, which emphasizes quasi-experimental evaluation; project sites were selected at random to enable rigorous comparisons of impact. While this approach has methodological advantages, it has created tensions and delays as provincial government were reluctant to agree to randomized selection of sites. The current quality of governance also varies widely in the selected districts (see Annex). Further, some randomly selected districts have very little interest in improving service delivery (for a host of local political and personal reasons), which directly impedes project implementation. Other districts are interested, but are newly established and have yet to develop the institutional capacity to absorb Kinerja’s packages of interventions. These complications may increase the reliance on the citizen participation pathway, in spite of the clear need to strengthen relations between district officials and service providers.

32

Implications

This rapid overview of Indonesia’s experience with service delivery improvement pathways reveals several emerging lessons regarding the questions of what has been learned about public sector reform, and of where reformers should go, moving forward. We review these according to the performance pathways previously discussed.

Decentralization: performance superhighway?

First and foremost is the primacy of the decentralization pathway for service delivery. Decentralization is perhaps primus inter pares relative to the other pathways in that it strongly influences the prospects for success of the other pathways discussed here. Without decentralized local governments, it is difficult to drive performance reforms top-down from the center when the long route to accountable performance is stretched so far.

As the above discussion highlights, the problematic elements of Indonesia’s decentralization, such as the lack of clarity on amounts and timing of intergovernmental transfers, delineation of expectations and responsibilities for services, and information flows detracts from its ability to contribute positively to better services. These problems also impede the workings of other pathways. They are symptomatic of the disconnects in the principal-agent relationships among various levels of government and service providers.

Numerous analyses have warned of the difficulties of ―getting it right‖ with

decentralization and the dangers of ―getting it wrong‖ (e.g. Crook and Manor 1998, Shah and

Thompson 2004, Devarajan et al. 2009). The ambitious nature of Indonesia’s decentralization has inevitably led to some missteps along the way, although significant progress has been made. However, to improve Indonesian services, more must be done to overcome financial,

33

responsibilities, and accountabilities between national and sub-national levels of government, as well as with service providers.

Indonesia’s experience with the decentralization pathway demonstrates the tension that Ahmad and Brosio (2009) note between local government autonomy and accountability for service delivery in the public interest, which includes delivery in conformance with technical standards. For example, the Indonesian state has a history of delivering free or highly subsidized basic health services through a system of district-level hospitals, complemented by clinics at the sub-district and village levels that focus on preventive care and maternal and child health. With decentralization, however, these services have suffered substantial decline (World Bank 2008,

2010). As local officials allocate resources to other uses than health, those basic services are starved into atrophy. Private providers (often state-employed healthcare workers supplementing their meager salaries) have taken on an increasing share of care, particularly to better-off

Indonesians who can afford to pay higher fees for improved access and service (Heywood & Choi 2010, Kristiansen & Santoso 2006). In the absence of policy clarity regarding national priorities and standards, and effective oversight mechanisms, the service-delivery performance enhancing potential of decentralization is at risk.

Standard-setting: promising but potential unfulfilled

34

the standards cost calculation tool (PBPSAP), the ability to assess costs associated with tracking and meeting standards is important for feasibility and sustainability. Finally, principals need both the capacity and the will to use performance results compared to standards as a criterion, for example, for accreditation, certification, staff promotion, and/or resource allocation. Otherwise, the extent to which this pathway can offer incentives to performance is limited. The Indonesia case highlights the institutional and political constraints to employing this pathway (Ferrazzi 2005, Buehler 2011).

Results-based management and performance-based payment: islands of

effectiveness

Indonesia has several examples of innovative experiments with results-based

management and PBP. The World Bank-supported pilot maternal and child health program that provided vouchers for poor women to access skilled birth attendants, and the CORDAID PBP experiment are just two cases where the benefits of performance incentives for service delivery have been documented. The PNPM stands out as a donor-initiated innovation that has been expanded to become a national program; Generasi is the latest innovation under that program. One lesson is that it is indeed possible to align principal-agent relationships in ways that contribute to better service delivery. Thus, Indonesia’s experience confirms what a variety of

analyses have found regarding results-based management and PBP (e.g., Eichler and Levine 2009, Brenzel et al. 2009).

However, a critical issue for broader impact and sustainability is how to move from these ―islands of effectiveness‖ to institutionalization (see Leonard 2010, McCourt and Bebbington

35

community-based model may not be sustainable in the future. Central government control of the program may be politically difficult to justify in the long term, but unless accountabilities between districts and both providers and communities are strengthened it is unlikely that the performance incentives that PNPM Generasi puts in place will operate as intended. This points to the importance of addressing capacity weaknesses at higher levels of government and of recognizing the political economy dimension, which affects public sector reforms of all stripes (see the concluding remarks below).

Information flows: input to the other pathways

Measuring, monitoring, and enhancing performance all depend upon information. This information needs to be available not simply to service providers and their principals, but to service users as well. The selected examples from Indonesia of efforts to place more information in the hands of local officials and citizens reinforce this lesson. Basic resource tracking and budget analysis tools enable performance comparisons on dimensions such as planned versus actual allocations, planned versus actual spending, distribution/equity of spending, and so on. Such financial information, along with service delivery output/outcome data, feed into

benchmarking, target setting, and monitoring for MSS.

36

may make sense to differentiate in terms of where satisfaction surveys have been shown to related to service quality: communities would monitor providers in partnership with sectoral oversight agencies through committees for meeting health targets and similar services where performance is poorly correlated with satisfaction; while satisfaction surveys would be employed for policing and infrastructure, where correlation with performance is high. The PNPM Generasi program is a particularly interesting example of community-based PBP, but as noted above, it has largely bypassed local governments, calling into question its broader institutionalization as part of a national policy to improve service delivery performance.

As many observers have remarked, Indonesia’s transition to democratic governance remains a work in progress. Some significant advances have been achieved in engaging citizens in the workings of the state; for example, in some jurisdictions re-energizing the often moribund participatory local planning system of musrenbang,the establishment of local parliaments or DPRDs, and incorporating citizen input into regulations and laws (Antlöv and Wetterberg 2011, Antlöv et al. 2008, MacLaren et al. 2011). However, the Indonesian public administration retains much of its pre-reformasi orientation that views citizen participation as unwelcome intrusion into the affairs of government (e.g., ADB 2004, Buehler 2011). Thus despite evidence that citizen participation can make a difference in service delivery improvement and in

increasing government responsiveness and accountability, moving from pilot experiments to policy and routine practice is a long-term reform challenge.

Concluding remarks

37

Indonesia is far from an anomaly. The international good governance agenda notwithstanding, clientelism and patronage are integral to the societal pacts that support state-society relations in most developing countries (Brinkerhoff and Goldsmith 2004). Various observers have noted the enduring power in Indonesia of old ingrained patterns of elite-dominated patronage politics and pervasive corruption (e.g., Blunt et al. 2012), and the shallow roots of reformist civil society and the forces for change, which some have referred to as the problem of ―floating democrats‖ (Törnquist et al. 2003).

The effects of Indonesia’s political economy on progress and prospects for the pathways to service delivery performance have been noted throughout the above discussion. The tendency of the current donor fashion for methodologically rigorous evaluation of the outcomes of

performance-enhancing interventions has reinforced a focus on the technical components of the interventions divorced from their institutional context. Yet, political economic factors strongly condition whether the experiments supported by international donors will be institutionalized, and indeed whether commitment to better performance is more than simply lip service to the donor-driven good governance agenda. They are of major import for the future of the most significant performance pathway: decentralization (see Lewis and Smoke 2011).

38

We conclude this overview of performance-based public management reforms not with pessimism for Indonesia’s prospects, but with realism in recognition of the fact that as there are forces in favor of political patronage and elite dominance, so there are also forces that continue to push for change. For service delivery improvement, we see the most effective level to work at being subnational, to support service provider incentive creation directly and to use citizen participation to push for better monitoring and more responsiveness. Tackling information systems and transparency to generate usable data to link to performance accountability can contribute to the building blocks for service delivery improvement, while reinforcing citizen capacity for voice and empowerment (e.g., SekNas FITRA). Projects like Kinerja are pursuing these routes, and can contribute to building the kind of knowledge that will help to answer not just the question of what works to enhance performance, but also to clarify under what

conditions service delivery performance can be improved and sustained.

References

ADB (Asian Development Bank) (2004) Country governance assessment report: Republic of Indonesia. Manila: ADB.

Ahmad E, Brosio G, (2009) Does decentralization enhance service delivery and poverty

reduction? In Ahmad E, Brosio G, eds. Does Decentralization Enhance Service Delivery and Poverty Reduction? Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 1-21.

Akbar R, Pilcher R, Perrin B (2010) Performance measurement in Indonesia: the case of local government. Paper presented at Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand, Annual Conference, Christchurch, NZ, July 4-6.

Andrews M, McConnell J, Wescott A (2010) Development as leadership-led change: a report for the Global Leadership Initiative. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Antlöv H, Wetterberg A (2011) Citizen engagement, deliberative spaces and the consolidation of a post-authoritarian democracy: the case of Indonesia. ICLD Working Paper. Visby, Sweden: Swedish International Center for Local Democracy.

Antlöv H, Brinkerhoff DW, Rapp E (2010) Civil society capacity building for democratic reform: experience and lessons from Indonesia. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 21(3): 417-439.

39

Azfar O, Kahkonen S, Meagher P (2001) Conditions for effective decentralized governance: a synthesis of research findings. College Park: University of Maryland, IRIS Center, Working Paper No. 256, March.

Banerjee A, Banerji R, Duflo E, Glennerster R, Khemani S (2006) Can information campaigns spark local participation and improve outcomes? A study of primary education in Uttar Pradesh, India. Washington, DC: World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper No. 3967. Bardhan P and Mookherjee D (2000) Relative capture of government at local and national levels.

American Economic Review 90(2): 135-139.

Batley R, Larbi G (2004) The Changing Role of Government: The Reform of Public Services in Developing Countries. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Birner R, von Braun J (2009) Decentralization and public service provision--a framework for pro-poor institutional design. In Ahmad E, Brosio G, eds. Does Decentralization Enhance Service Delivery and Poverty Reduction? Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 287-316.

Blunt P, Turner M, Lindroth H (2012) Patronage's progress in post-Soeharto Indonesia. Public Administration and Development 32(1): 64-82.

Bouckaert G (1992) Public productivity in retrospective. In Holzer M, ed. The Public Productivity Handbook. New York: Marcel Dekker, 5-46.

Brenzel L, Measham A, Naimoli J, Batson A, Bredenkamp C, Skolnik R (2009) Taking stock: World Bank experience with results-based financing (RBF) for health. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Brinkerhoff DW (2011) Community engagement in facility-based quality improvement in the Philippines: lessons for service delivery and governance. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, Health Systems 20/20, Policy Brief, December.

Brinkerhoff DW (2005) Accountability and good governance: concepts and issues. In Huque AS, Zafarullah H, eds. International Development and Governance. New York: CRC Press, 269-289.

Brinkerhoff DW, Goldsmith AG (2004) Good governance, clientelism and patrimonialism: new perspectives on old problems. International Public Management Journal 7(2):163-185. Brinkerhoff DW, Fort C, Stratton S (2009) Good governance and health: assessing progress in

Rwanda. Kigali: US Agency for International Development, Twubakane Decentralization and Health Program, April.

Brinkerhoff DW, Wetterberg A, Dunn S (2012) Service delivery and legitimacy in fragile and conflict-affected states: evidence from water services in Iraq. Public Management Review

14(2): 273-293.

Buehler M (2011) Indonesia's Law on Public Services: changing state-society relations or continuing politics as usual? Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 47(1): 65-86. Camm F, Stecher BM (2010) Analyzing the operation of performance-based accountability

systems for public services. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, Technical Report. Crook RC and Manor J (1998) Democracy and Decentralization in South Asia and West Africa:

Participation, Accountability and Performance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

40

Deichman U, Lall SV (2007) Citizen feedback and delivery of urban services. World Development 35(4): 649-662.

Devarajan S, Khemani S, Shah S (2009) The politics of partial decentralization. In Ahmad E, Brosio G, eds. Does Decentralization Enhance Service Delivery and Poverty Reduction?

Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 102-121.

Dillinger W (1994) Decentralization and its implications for service delivery. Washington, DC: World Bank and United Nations Development Programme, Urban Management

Programme.

Dubnick MJ, Frederickson HG (2011) Public accountability: performance measurement, the extended state, and the search for trust. Washington, DC: National Academy of Public Administration and the Charles F. Kettering Foundation.

Dunleavy P, Hood C (1994) From old public administration to new public management. Public Management and Money 14(3): 9-16.

Eaton K, Kaiser K, Smoke PJ (2011) The political economy of decentralization reforms. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

Eichler R, Auxila P, Antoine U, Desmangles B (2007) Performance-based incentives for health: six years of results from supply-side programs in Haiti. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development, Working Paper No. 121, April.

Eichler R, Levine R, eds. (2009) Performance Incentives for Global Health: Potential and Pitfalls. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Eldridge C, Palmer N (2009) Performance-based payment: some reflections on the discourse, evidence and unanswered questions. Health Policy and Planning 24: 160-166.

Ellis P, Mandri-Perrott C, Tineo L (2011) Strengthening fiscal transfers in Indonesia using an output-based approach. Washington, DC: World Bank, OBApproaches, Vol. 40. Evans P (1996) Government action, social capital and development: reviewing the evidence on

synergy. World Development 24(6): 1119-1132.

Ferlie E, Ashburner L, Fitzgerald L, Pettigrew A (1996) The New Public Management in Action. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ferrazzi G (2005) Obligatory functions and minimum service standards for Indonesian regional government: searching for a model. Public Administration and Development 25(3): 227-238.

Friedman J (2011) Sticking to the numbers: performance monitoring in South Africa, 2009-2011. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and

International Affairs and Bobst Center for Peace and Justice, Innovations for Successful Societies, Case Study, August, www.princeton.edu/successfulsocieties.

Gorter A, Sandiford P, Rojas Z, Salvetto M (2003) Competitive voucher schemes for health. Managua, Nicaragua: Central American Institute for Health (ICAS).

Heckman JJ, Heinrich C, Smith J (2002) The performance of performance standards. Journal of Human Resources 37(4): 778-811.

Heinrich CJ (2002) Outcomes-based performance management in the public sector: implications for government accountability and effectiveness. Public Administration Review 62(6): 712-726.

Heyward M, Cannon RA, Sarjono (2011) Implementing school-based management in Indonesia. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press, Research Report.