Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 20:18

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

VILLAGE GOVERNMENT AND RURAL

DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THE NEW

DEMOCRATIC FRAMEWORK

Hans Antlöv

To cite this article: Hans Antlöv (2003) VILLAGE GOVERNMENT AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN INDONESIA: THE NEW DEMOCRATIC FRAMEWORK, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 39:2, 193-214, DOI: 10.1080/00074910302013

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910302013

Published online: 17 Jun 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 330

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/03/020193-22 © 2003 Indonesia Project ANU

One need not underestimate the real eco-nomic progress of Soeharto’s rural de-velopment programs to recognise the negative social, political and cultural impact his New Order regime had on village communities. Hand in hand with the emphasis on development went a political imperative, the need to main-tain order and political control in the countryside. Thus village elites were cultivated by economic and political means, and recruited as loyal clients of the New Order regime. A thumbnail description of development strategy under the New Order would include an ‘opening up’ of the economy to foreign investment and capitalist development, a ‘reaching out’ of the state into almost all aspects of village life, and a ‘closing down’ of politics, allowing no ideology other than that sponsored by the state. It was a fine example of top-down de-velopment (Schulte Nordholt 1981;

Hardjono 1983; MacAndrews 1986; Hart 1986; Maurer 1986; Quarles van Ufford 1987; Booth 1988; Hüsken 1988; Hart 1989; Hüsken and White 1989; Schweiz-er 1989; Antlöv 1995; and CedSchweiz-erroth 1995).

The price of state intervention in peo-ple’s lives and of this managerial ap-proach to economic development was high. Uniformity and standardisation, destruction and twisting of the social fabric, distortion of local leadership, abuse of power, and widespread rent seeking and corruption were but some of the more acute and obvious costs (Antlöv 2003a). The political scene became tightly monopolised and con-trolled by state-backed leaders. Commu-nity-based institutions were coopted and corrupted, and lost their credibili-ty. The New Order’s seemingly well in-tegrated system of ideology, legal formalism, administration and

develop-VILLAGE GOVERNMENT AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN

INDONESIA: THE NEW DEMOCRATIC FRAMEWORK

Hans Antlöv

Ford Foundation, Jakarta

The political reforms that began in Indonesia in 1998 have created new opportuni-ties for a revised relationship between state and community, replacing the New Or-der’s centralistic and uniform framework with local-level institutions that are strong and responsive. This paper presents the new legal framework for the democratisa-tion of local-level politics and village institudemocratisa-tions. Representative councils have been elected in all Indonesian villages, and the village head is no longer the sole authority in the community. Village governments are provided with far-reaching autonomy and do not need the approval of higher authorities to take decisions and implement policies. However, decentralisation and democratisation are necessary but not suffi-cient preconditions for developing the countryside and alleviating poverty. An ac-tive government and civil society engagement must ensure that regulations are not distorted during implementation, and that ordinary people are included in public policy making and local governance.

mentalism provided little room for pub-lic shows of dissatisfaction.

Given the negative social conse-quences of past policies—and the ulti-mate failure of the New Order regime to hold on to power—it would seem safe to conclude that Indonesia will not en-gage in centralised and interventionist programs of rural development in the foreseeable future. Nor is this the time to do so; the country’s main aid do-nors—the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank—have left these large-scale state-sponsored projects be-hind. There will probably not be any grand schemes at all to develop the In-donesian countryside. Instead, the present government is promoting a far-reaching and radical process of de-centralisation and regional autonomy— codified in Law 22 of 1999 on Regional Governance and Law 25 of 1999 on the Fiscal Balance between the Centre and the Regions—which is pushing poverty alleviation and rural development schemes down to provinces and districts (Hidayat and Antlöv forthcoming; Daly and Fane 2002).

The reforms that began in 1998 have created new opportunities for a revised relationship between state and commu-nity. There is today a momentum to re-place the New Order’s centralistic and uniform framework with local-level in-stitutions that are strong, responsive and effective. People across Indonesia are promoting a new paradigm, based on local knowledge, autonomy, and sus-tainable and equitable development.

This article investigates the emerging new democratic framework for local governance and autonomy in Indo-nesia’s 62,500-odd villages, and consid-ers the consequences this will have for future rural development programs. It argues that decentralisation and democ-ratisation are necessary but not

suffi-cient preconditions for developing the countryside and alleviating poverty. There must also be active government and civil society engagement to ensure that regulations are not distorted dur-ing implementation, and there must be regulations and practices that ensure that ordinary people, and not only the elite, are included in public policy mak-ing and local governance at community level.

THE NEW ORDER LEGAL FRAME-WORK FOR VILLAGE

GOVERNANCE

The late colonial and early indepen-dence period was characterised by what John Legge (1961: 21) called ‘a rather confusing body of legislation’. Colonial legislation recognised village govern-ments but did not actually regulate them—it encouraged self-rule and thus reinforced the diversity of existing forms.1 Its aim was to incorporate vil-lages into the state administration, preserving their right to organise in tra-ditional ways but making them the low-est administrative unit and allowing them to be taxed (Breman 1980).

This diversity of government forms was later incorporated into the young Republic through the 1945 Constitution, in which the government recognised ‘the approximately 250 self administer-ing units and communities … such as the desa in Java and Bali, the nagari in Minangkabau [West Sumatra], the

dusun and marga in Palembang [South Sumatra] …’. The Constitution went on to say: ‘The Republic of Indonesia re-spects the status of said special regions and all State regulations regarding them shall pay heed to [mengingati] their his-torical rights [hak asal-usul].’2 This view became the official position of subse-quent legislation during the Soekarno period. Law 22 of 1948 on Regional

ernment, Law 1 of 1957 on Basic Region-al Government, and finRegion-ally Law 19 of 1965 on Village Government [ Desapra-ja] reinforced the right of villages to or-ganise themselves within a unitary Republic of Indonesia.

Coming into the New Order, there was thus a confusing mixture of more or less autonomous government struc-tures often coexisting with strong re-gional sentiment (as exemplified by the regional rebellions of the 1950s). Fur-thermore, the village was to a large ex-tent beyond the reach of the central government (as illustrated in the East Java study of Jay 1969). This was not conducive to the control and access needed by Soeharto: he wished to de-sign a uniform structure and a clear hi-erarchy giving the central government power over local communities. The ex-isting legislation was therefore insuffi-cient. The new framework was outlined in Law 5 of 1979 on Village Governance and its subsequent implementing de-crees, regulations and technical guide-lines.

According to the logic of Law 5/1979, the two pillars of the New Order— economic development and national stability—could be achieved only if the centre was in full control of the coun-tryside, supervising village government. To ‘sustain development in all sections across Indonesia and to achieve the na-tional aspirations of Pancasila—a just and prosperous society, material as well as spiritual, for the people of Indo-nesia—there is a need to strengthen village government’ (Law 5/1979, Elu-cidation, section 1.3). The architects of the New Order used local communities as vehicles to achieve development and stability and, indirectly (by delivering these ‘goods’), legitimacy. Local com-munities had to be made ‘legible’ and simplified so that the New Order

gov-ernment could achieve its aims of con-trol and manipulation.3

With the passage of the 1979 law, vil-lage affairs were brought firmly under the supervision and control of higher authorities, and village structures were recast within a single homogeneous mould, designed by the Department of Home Affairs in Jakarta and tightly pre-served by an army of loyal extension officers and village branches of state organisations. Communities were stan-dardised (penyeragaman bentuk— Elucidation, section 4), effectively dis-allowing—and in the process virtually destroying—traditional governance structures. It was a regimentation of village life that would deeply and neg-atively affect communities for decades— it destroyed community institutions and traditional social security mechanisms. The first paragraph of Law 5/1979 clearly defined the subordinate nature of the village: it was ‘the lowest level of the government structure directly under the subdistrict head’ (organisasi pemerin-tah terendah langsung di bawah Camat, paragraph 1). While the law stated that the village had ‘the right to manage its own affairs’, it immediately noted that this ‘does not mean autonomy’ (Eluci-dation, section 7). The village head was ‘positioned as the instrument of the cen-tral government, of the regional govern-ment and of the village governgovern-ment’ (Law 5/1979, paragraph 3.1). Village heads owed their power to higher au-thorities, and could do little without the approval of subdistrict and district gov-ernments. Village decisions and the vil-lage budget required approval (pengesahan) by the district chair (Elucidation, para-graph 19). This meant the total submis-sion of the village heads and, through them, the village population, in which there was no room for innovation from below or for aspirations (political or

erwise) that did not accord with those of higher authorities (Schulte Nordholt 1981; Hüsken 1988; Antlöv 1995; Hol-land 1999). Village administrations became for all practical purposes min-iature replicas of the central govern-ment, enforcing decrees and policies determined from above. A myriad of government agencies were present in the countryside and various ministries set up programs and institutions in ev-ery village. ‘Electricity Comes to the Vil-lage’ (Listrik Masuk Desa), ‘The Military Comes to the Village’ (ABRI Masuk Desa), ‘Television Comes to the Village’ (TV Masuk Desa), ‘Student Community Service’ (Kuliah Kerja Nyata) and a vari-ety of other government programs firm-ly incorporated the village into the Indonesian state. Although this was part of a modernisation process that took place simultaneously in other Asian countries, rural development in Indo-nesia was intricately connected with the New Order state. In a variety of ways, citizens learnt that economic progress was the product of the New Order and, ultimately, of President Soeharto, on whom the People’s Consultative Assem-bly (MPR) in 1983 bestowed the official title of ‘Bapak Pembangunan Indonesia’ or ‘Father of Indonesian Development’.4 The authority and power of village leaders came from their contacts with higher authorities, and they became what I have described elsewhere as ‘clients of the state’ (Antlöv 1995: ch. 7–8). Whether lured by privileged access to funds or forced by intimidation, vir-tually all leaders, local notables and people with prestige and authority in-evitably became state clients. Signifi-cantly, these state clients were not foreign officials arriving in government jeeps: they were community leaders, people’s neighbours. Their presence in everyday life—praying next to you at the mosque, sharing a meal at the local

food stall, cheering the same team at a soccer match—was an important factor in explaining the stability and legitima-cy of the New Order. Since these lead-ers represented multiple forms of power (as religious teachers, as local notables, as landlords, as village officials), if one source of authority dried up they could always rely on other sources. The struc-ture of local politics built by the New Order government was thus based on intimate personal relations and on pa-tronage.

Two government decrees codified this system of state monopoly and pa-tronage. An MPR decision in 1971 out-lined the principle of the ‘floating mass’ (massa mengambang). This decision (lat-er codified in Law 3 of 1975 on Political Organisations) banned political activi-ties below the district level, signalling the end of political pluralism and the last hope of democracy under the New Or-der—only the state party, Golkar (Soe-harto’s electoral machine), was allowed to organise in the countryside. A second piece of legislation, a 1970 Presidential Instruction (Inpres No. 6/1970), intro-duced the principle of ‘singular loyalty’ (mono-loyalitas), forcing all civil ser-vants—and this in practice also includ-ed village officials—to support Golkar (Reeve 1985: 288). Members of the vil-lage elite were thus forced to focus on maintaining good relations with higher authorities, at the expense of relations with the local population who were their neighbours.

Village leaders, the loyal state clients, became the axis around which gover-nance, politics and funds circulated. So while heads were powerless in relation to higher authorities, they were, in ex-change for their subordination and loy-alty, endowed with almost unlimited powers within their community. Each became the ‘sole authority’ (kuasa tung-gal) and the most powerful figure in the

village. Paragraph 3 of Law 5/1979 de-fined the village government as consist-ing of two parts: the head (and his staff) and the Village Consultative Assembly (Lembaga Musyawarah Desa, LMD). However, there was no separation of powers between the head and the LMD. The head was ex officio the chair of the LMD, and the village secretary was ex officio LMD secretary (as was the case with the Village Community Resilience Board, the Lembaga Ketahanan Ma-syarakat Desa, LKMD).5 Other members were appointed directly by the head, in consultation with the subdistrict govern-ment and, typically, the Babinsa (Bint-ara Pembina Desa, the Village Guidance Army Officer). The LMD had no impor-tance in the village, beyond ‘rubber-stamping’ the head’s decisions. The village government was responsible only to higher authorities, represented by the subdistrict chair (Law 5/1979, paragraph 10.2). There were no mecha-nisms for the village population to hold the village head accountable. The head was in a very paradoxical situation: ex-tremely powerful in the village but vir-tually powerless in relation to higher authorities.6 The result was a village leadership that was both weak and coopted (seen from above) and strong and authoritarian (seen from below), and one that certainly was not respon-sive to the village population.

THE POST-1999 LEGAL FRAME-WORK FOR VILLAGE

GOVERNANCE

This was the situation during the two decades between 1979 and 1999. There have been a number of far-reaching changes since—not only democratisa-tion but, equally importantly, a process of decentralisation, providing autono-mous decision making to districts and villages through Law 22 of 1999. Else-where I have discussed in more detail

the decentralisation aspects of Law 22/ 1999 (Hidayat and Antlöv forthcoming); I here note only some of its more prom-inent features. The first is the autonomy given to district governments. In the past, services were deconcentrated to local governments, but decision making was retained in Jakarta. With Law 22 and its sister Law 25 on financial devo-lution, districts and municipalities have the leverage to raise their own revenues, deliver services and decide upon local policies without interference from high-er authorities (this includes policies on villages). The other new feature of Law 22/1999 is the separation of powers be-tween the executive and legislative branches of government, and the em-powerment of local people’s represen-tative councils (DPR-D), which are no longer merely ‘rubber-stamping’ deci-sions taken by the executive.

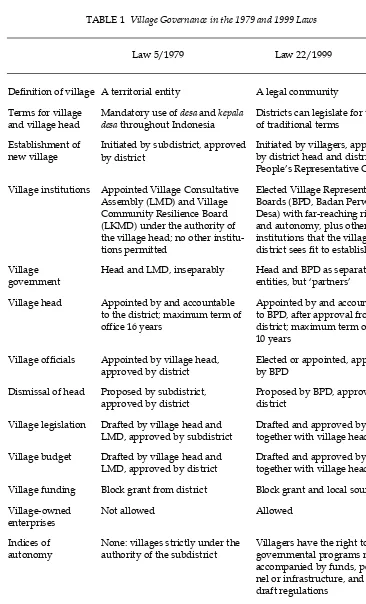

However, Law 22/1999 not only out-lines district-level decentralisation; im-portantly it also replaces Law 5/1979 on Village Governance. The sections of Law 22/1999 outlining village governance are in paragraphs 93 to 111. Table 1 sum-marises the important differences be-tween Laws 5/1979 and 22/1999.

This comparison between the two laws conveys their different character and intent. Law 22/1999 clearly states (Elucidation, section 9.1) that the basis for the new regulations on village gov-ernment is ‘diversity, participation, gen-uine autonomy, democratisation and people’s empowerment’. Even though these concepts reflect high moral prin-ciples whose practice may be fairly shal-low, there is a sense of real change in the law. The preamble (point ‘e’) says that ‘Law 5 of 1979 … was not in accor-dance with the spirit of the 1945 Consti-tution, and it is necessary to recognise and respect the right to uphold specific regional origins’. The law was passed in May 1999, one month before the

TABLE 1 Village Governance in the 1979 and 1999 Laws

Law 5/1979 Law 22/1999

Definition of village

Terms for village and village head

Establishment of new village

Village institutions

Village government

Village head

Village officials

Dismissal of head

Village legislation

Village budget

Village funding

Village-owned enterprises

Indices of autonomy

Implementation and oversight

A legal community

Districts can legislate for the use of traditional terms

Initiated by villagers, approved by district head and district People’s Representative Council

Elected Village Representative Boards (BPD, Badan Perwakilan Desa) with far-reaching rights and autonomy, plus other institutions that the village or district sees fit to establish

Head and BPD as separate entities, but ‘partners’

Appointed by and accountable to BPD, after approval from district; maximum term of office 10 years

Elected or appointed, approved by BPD

Proposed by BPD, approved by district

Drafted and approved by BPD together with village head

Drafted and approved by BPD together with village head

Block grant and local sources

Allowed

Villagers have the right to reject governmental programs not accompanied by funds, person-nel or infrastructure, and to draft regulations

District government and People’s Representative Council A territorial entity

Mandatory use of desa and kepala desa throughout Indonesia

Initiated by subdistrict, approved by district

Appointed Village Consultative Assembly (LMD) and Village Community Resilience Board (LKMD) under the authority of the village head; no other institu-tions permitted

Head and LMD, inseparably

Appointed by and accountable to the district; maximum term of office 16 years

Appointed by village head, approved by district

Proposed by subdistrict, approved by district

Drafted by village head and LMD, approved by subdistrict

Drafted by village head and LMD, approved by district

Block grant from district

Not allowed

None: villages strictly under the authority of the subdistrict

Ministry of Home Affairs

cratic national elections, and hence the People’s Representative Council (DPR) that passed it was still that elected in 1997; this New Order-era DPR thus pub-licly acknowledged that Law 5/1979 vi-olated the spirit of the Constitution. (The same criticism is raised against Law 5/ 1974 in point ‘d’ of the preamble). It had become clear that Law 5/1974 and Law 5/1979 provided a framework that was too narrow, rigid and authoritarian. Aspirations from below, diversity and local conditions were not accommodated. Law 5/1979 had become part of the problem it was originally intended to solve: how to reg-ulate villages and structure their govern-ment in the most efficient way. So although there was very little public pressure to revise Law 5/1979, the Min-istry of Home Affairs decided to aban-don it and replace it with the new Law on Regional Governance.

The section of Law 22/1999 on village government appears fairly favourable to local democracy—more so than most people expected of the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Soeharto-era DPR. The law has four major democratic features. First it ‘liberates’ the village from the authority of higher levels of govern-ment. The village is no longer under the authority of the subdistrict, but is an autonomous level of government.7 Importantly, a village is a legal commu-nity (kesatuan masyarakat hukum, para-graph 1.o), rather than a territorial entity (suatu wilayah yang ditempati oleh sejum-lah penduduk sebagai kesatuan masyarakat, Law 5/1979, paragraph 1.o). It has the right to raise funds, and does not need to consult with or have approval from higher authorities to pass village regu-lations or budgets. Villages even have the right to reject projects from other levels of government if they are not ac-companied by funds, personnel and in-frastructure (Elucidation, paragraph

100), and to act as entities in legal mat-ters (Elucidation, general section 9.3).

Second, Law 22/1999 provides space for diversity and responsiveness to lo-cal aspirations. According to paragraph 1.o, a village can be called by any tradi-tional name (desa atau yang disebut den-gan nama lain): in West Sumatra nagari, in Central Sulawesi lembang, in South Sumatra marga, and so on (paragraph 1.o).8 The village is to be ‘based on local origins and customs’ (berdasarkan asal-usul dan adat-istiadat setempat) (para-graph 1.o). The same is true for the position of village head: whatever tra-ditional concept was in use before the old law came into effect can again be used. (The right to change the name is devolved to local DPR-Ds.)9

The third democratic feature is the introduction of village councils (Badan Perwakilan Desa, BPD), replacing the ill-reputed LMD. The BPD is a democratic village organisation, consisting of 5–13 members, depending on village size, elected ‘by and from villagers’ (para-graphs 104–5). The BPD has the power to draft village legislation, to approve the village budget, and to monitor vil-lage government. It even has the right to propose to the district chair that the village head be removed (though the decision is taken by the district govern-ment). This is a clear departure from the past, when higher authorities, through the village head, decided what the vil-lage needed and wanted. Local regula-tions and budgets are now to be decided jointly by the BPD and the village head, and higher authorities need only to be informed of their decisions.

Fourth, and related to the above, is the accountability of the village govern-ment (Bennett 2002). While Law 5/1979 stated that the village government consisted jointly of the village head and the LMD, and that they were account-able only to the subdistrict office, Law

22/1999 provides for a separation of powers. The reformed village govern-ment consists of the head and his staff, and the BPD (paragraph 94). The village head is responsible to the village popu-lation through the BPD; he must submit an annual accountability report, which the BPD can contest. He must also pro-vide a report each year to the district chair, but this report is only an admin-istrative matter and cannot be contest-ed (paragraph 94). The village head is thus not primarily oriented upwards; rather he is accountable to the village population and must answer questions at BPD meetings.

These regulations constitute nothing less than a quiet revolution in the coun-tryside, not only providing a mechanism for checks and balances in village government, but also revising the old paradigm of villagers as objects of development to one in which villagers have the right to exercise their demo-cratic authority over public matters. The authority and autonomy of the BPD is far greater than that of the former LMD. The BPD is nothing short of a village par-liament, the community-level legislative body, with all the democratic expecta-tions that come with such a function. There is to be no political screening of candidates to the village headship or the BPD, although candidates must fulfil certain criteria, including a minimum education level and a maximum age (and they must adhere to the 1945 Con-stitution and the state ideology, Panca-sila). The previously mandatory (and controversial) LKMD (note 5) has an un-certain future. Law 22/1999 states that the village has the right to establish in-dependent organisations as it sees fit. The LKMD is not referred to in the law, although, as we shall see, an implement-ing regulation mentions it and the equal-ly discredited women’s organisation

PKK (Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluar-ga, the Family Welfare Association) as examples of such organisations (Kep-men 64/1999, paragraph 45).

There are two further regulations that carry significant consequences for village democracy and autonomy. Pres-idential Decree 5/1999, signed by then President B.J. Habibie on 26 January 1999, is a little known regulation that soberly states that civil servants may not be active members of political parties. This was part of the revision of the elec-toral system ahead of the 1999 elections, but it has had consequences far beyond that. In effect, it means that the princi-ple of mono-loyalitas is abolished. At around the same time, the ‘floating mass’ principle was also abandoned, through Law 2 of 1999 on Political Par-ties, which states (paragraph 11) that po-litical parties may have branches at subdistrict and village levels. Together, these provisions mean that the control that Golkar and the government once held over civil servants and village lead-ers has been dismantled. Golkar is no longer the sole political authority in the village, and village officials are no long-er ‘clients of the state’. A plurality of voices, leaders and parties has emerged.

THE IMPLEMENTING REGULATIONS

A law provides the framework for what is legally possible, but it is only in its implementation that we can know whether the possibilities are realised. I now move beyond the national-level legislation to the implementing regula-tions—the ministerial decrees, technical instructions and district regulations. I then discuss how these have been exe-cuted in practice in a village in West Java.

As one of the first implementing reg-ulations of Law 22/1999, Ministerial

Decision (Kepmen) 64/1999 on General Guidelines for Village Regulations, is-sued by the Minister of Home Affairs, was adopted by the Habibie cabinet in September 1999. Unfortunately, this reg-ulation introduced some quite serious distortions of the spirit of the law. For instance, while Law 22 (paragraph 104) states that village regulations are pro-duced by the BPD, Kepmen 64 (para-graph 48) mentions ‘village regulations produced by the village head and/or the BPD’. Nor is the regulation internally consistent: paragraph 16.1.g states that village regulations are created jointly by the head and the BPD. The democratic distortion continues in the references to the annual budget. According to Law 22/1999 (paragraph 107.3), ‘the village headman together with [bersama] the BPD determines the village budget’ (my em-phasis). In Kepmen 64 (paragraph 60) this right is given to the village head, without mention of the BPD; the only right given to the BPD in relation to the budget is one of supervision (paragraph 36.c). Given the strong powers of the village government under the New Or-der, such weak formulations could in practice allow the village head effective-ly to bypass the BPD. Furthermore, the separation of powers between the vil-lage head and the BPD is muddled in Kepmen 64. While Law 22 clearly states that the village head is responsible to the BPD through an annual accountability report, the interpretation given in Kep-men 64 is that the BPD ‘sits on the same level [as] and as a partner to the Village Government’ [BPD berkedudukan sejajar dan menjadi mitra dari Pemerintah Desa] (paragraph 35). Kepmen 64 also states that the ‘other institutions’ [Lembaga Lain]that are allowed under Law 22 , to develop community life in the country-side (paragraph 106), must have a development planning focus, and

mentions the (discredited) New Order LKMD and PKK as examples of such institutions (Kepmen 64, paragraph 45–47). I could continue, but the gener-al point about distortion of the intent of Law 22/1999 has been made.

Critics have argued that the imple-menting regulations, and particularly Kepmen 64, depart from the spirit of Law 22/1999 by elaborating too much on the structure of village government (FPPM 2001; Zacharia 2000; Juliantara 2002). Rather than allowing for local variation, Kepmen 64/1999 details what the village government should look like, stipulating, for example, the 13 require-ments of a candidate for village head.10 What the regulation should have done, commentators have argued, is provide the general regulations for the establish-ment of various village institutions and leave the details of the institutions them-selves for local governments to deter-mine (see, for example, FPPM 2001, the Academic White Paper produced by the Forum for Popular Participation [Forum Pengembangan Partisipasi Masyarakat], a non-governmental network of com-munity activists and village governance researchers).

These distortions become even stark-er in the 13 implementing regulations that each of Indonesia’s 288 districts (the 2003 figure) is required by Kepmen 64/1999 to draft, on subjects ranging from BPD elections to village enterpris-es. Even by late 2002, more than three years after Law 22/1999 and Kepmen 64 were passed and two years after the legislation came into effect, many dis-tricts, according to Home Affairs offi-cials, had yet to complete all the decrees. We cannot look systematically at even a fraction of what might eventually be close to 3,000 district decrees, but it may be interesting to investigate one partic-ular case.

The 13 district decrees (Peraturan Daerah—Perda) in the West Java high-land district of Sumedang were signed by the district chair on 4 March 2000, after having been drafted by the district secretariat and approved by the local DPR-D. The decrees begin by repeating the basic text of Kepmen 64 word by word, including the inconsistencies with Law 22/1999, such as that the BPD is a partner to the local government and that village regulations are formulated joint-ly by consensus between these two par-ties. In their elaboration, many decrees introduce further potential conflicts with Law 22/1999. For instance, Perda 30/2000, on the establishment, election and duties of the BPD, introduces a re-quirement for ‘administrative selection’ of candidates. This might sound like a harmless formula, but because elections for village head during the New Order were tightly controlled, in part through political screening of candidates, men-tion of ‘selecmen-tion’ in Indonesia evokes memories of a not too distant past in which higher authorities could control who was to be elected.

The Decree on Community Organi-sations (38/2000) distorts even further the intent of Law 22/1999. After repeat-ing the misinterpretation that other village-level institutions can be active only in development planning, and de-tailing their internal structure, para-graph 8 states that existing community organisations (and LKMD and PKK are again specifically mentioned) should ‘be made to conform [disesuaikan] with these regulations’. In practice, this means that the ‘community organisations’ in Su-medang are the unpopular LKMD and PKK, and little more than this. A further example is Perda 39/1999 on the ‘Empowerment, Preservation and De-velopment of Tradition, Customs and Traditional Institutions’. Paragraph 4.4

of this decree states that the ‘objective of developing traditions and customs is to raise their roles to support the process of economic development and national sta-bility’ (my emphasis). This carries more than a hint of the New Order spirit of cultural engineering—social institutions are instrumental in character and they must be developed with certain politi-cal aims in mind. Nothing of the kind is found in Law 22/1999.

One weakness in Law 22/1999 is that a number of paragraphs are very loose-ly worded and thus open to more than one interpretation. For example, in the section on BPD elections, Law 22/1999 states simply that ‘members of the BPD should be elected from and by villagers’ (paragraph 105). This is a great improve-ment on Law 5/1979 in which the vil-lage head, who chaired the LMD, also appointed its members. But since Law 22/1999 does not specify how the elec-tions should be organised, local govern-ment has at times interpreted this (in particular, the word ‘elected’) in ways that are less than democratic (Antlöv forthcoming). Some districts are using what they call formatur or electoral col-leges (in the US sense), appointed by hamlets, to elect village heads. Other districts allow only household heads to vote in the BPD election, thus disenfran-chising the majority of women. Most districts use direct elections (similar to the kind used to elect the village head), but the vagueness of Law 22/1999 has nonetheless allowed a degree of vari-ance in practice.

We now go one step further down the legal hierarchy, to the Technical Instruc-tions (Petunjuk Pelaksanaan, or Juklak) that are distributed by a district govern-ment to villages to provide technical assistance in executing a district decree. In Petunjuk Pelaksanaan2/2000 on BPD Elections in Sumedang, the

cies with Law 22/1999 continue: the Sumedang decree on BPD elections states that ‘a BPD Electoral Commission shall be established’ (a commission not mentioned in Law 22 or Kepmen 64); the technical instruction takes this one step further, stating that the electoral com-mission ‘shall be established by the Vil-lage Government’. The Juklak repeats that the commission has the right to ‘se-lect administratively’ who can be a BPD candidate. It also states that the various ‘village powers’ must ‘consult’ with the village government to identify potential candidates. This provides the legal framework for the village head to reject electoral commission candidates on ad-ministrative grounds, and to appoint loyal followers to the commission, which then decides who may stand for election to the BPD.

We have in this section noted the gradual deterioration of the democratic character of village government regula-tion as it moves down the administra-tive ladder. While Law 22 outlined the legal framework for a more democratic and responsive village government, the end result, as the law has been imple-mented, is an overregulated and, in im-portant respects, pseudo-democratic body of regulations, decrees and instruc-tions that outline in detail what village government must look like, and do not acknowledge local variation and self-de-termination. Since we can expect that village governments will implement whatever technical instructions they re-ceive from higher authorities (whether district or central government), rather than the ‘spirit’ of the law itself, which few village heads will read, this is a se-rious distortion.

There is a technical legal issue here. Since Law 22/1999 is the higher-level law, implementing regulations may not contradict it. There are at the

Depart-ment of Home Affairs today hundreds of Perda that appear to contradict Law 22. Reviewing these is a time consum-ing and messy process and, to this author’s knowledge, none of the regu-lations on village governance has yet been challenged.

These distortions and the practices they allow have to a certain extent been recognised by the Ministry of Home Af-fairs, and Kepmen 64/1999 has been re-vised. It was replaced in November 2001 by Government Regulation (PP) 76 of 2001, ‘General Guidelines for Village Regulations’.11 Unfortunately, only mi-nor details have been changed; the ba-sic distortions remain. Meanwhile, the thousands of District Regulations intro-duced under Kepmen 64/1999 are still in force.

Many civil society groups, communi-ty activists and researchers are urging that mechanisms of public participation and transparency should be put at the forefront of a possible revision of Law 22/1999. At a meeting on 23 August 2001 organised by the Ministry of Home Affairs and FPPM, the above mentioned draft White Paper presented by FPPM described the ideal village community (FPPM 2001). The term used by this civil society consortium is ‘village commu-nity autonomy’ (otonomi masyarakat desa), not ‘village autonomy’ (otonomi desa) as the government proposes. This is a crucial distinction, since it locates governance issues at the lowest level, in communities, empowering people and not government. It is the people of the village that should be given the right to decide their own future, not the village government. In order to achieve this, FPPM has suggested quite radical changes to Law 22/1999. Rather than introducing forms, such as the BPD and village head, the draft White Paper proposes that the revised law should

troduce the functions of a village govern-ment and a legislative body, and allow regions, or perhaps even villages, to de-cide the forms for themselves. The cen-tral government should only make sure that the functions mentioned in the law, which include mechanisms of transpar-ency, power sharing and accountabili-ty, are properly carried out by villages. In arguing this, FPPM is placing the emphasis on the method by which the institutions of village governance are put in place, rather than the form that those institutions take.

THE REGULATIONS IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY FROM WEST JAVA

Law 22/1999 came into effect on 1 Jan-uary 2001. Elections to BPDs have been held across the country from mid 2000, and new governance and leadership structures are slowly emerging, replac-ing the institutions of the New Order. This section discusses the workings of the BPD and post-reformasi rural lead-ership as I have observed them in the village of ‘Sariendah’ (not its real name), just outside the town of Majalaya in the West Java district of Bandung. This is a community that I have followed for the past 15 years (see Antlöv 1995 for a full monograph on the village).

Sariendah is a modern, semi-urban village some 20 minutes by frequent minibus from Majalaya, the former tex-tile centre of Indonesia, with hundreds of small factories still producing woven cloth for domestic consumption. More than half the population of Sariendah works in textile factories, some in Maja-laya, others in Sariendah. During the past two decades, impressive economic growth has created an incipient middle class in the village (Antlöv 1999). Some 15 years ago, Sariendah had no electric-ity. Today, there is a video rental shop and a computer software stall. Govern-ment programs in agriculture, credit

schemes, family planning and education have been implemented fairly success-fully. Sariendah has more than once won the ‘Best Village’ competition held each year in the subdistrict.

Until 1998 Sariendah was a Golkar stronghold. Almost all local notables were recruited—encouraged, persuad-ed, coopted or coerced—into the village bureaucracy. In the mid 1980s, the vil-lage administration consisted of some 178 official positions in 18 organisations, including the LMD, the LKMD, the Is-lamic Teachers Council (Majelis Ulama), the Association of Active Youth (Karang Taruna), and the neighbourhood admin-istrative units, Rukun Warga and Rukun Tetangga (Antlöv 1995: 51–5). But there was not a fair distribution of public of-fices in Sariendah. With few exceptions, leaders were from the village elite, and important political offices were distrib-uted among a restricted number of fam-ilies: the 178 offices were occupied by 95 persons; of these, 49 persons held one position, 30 held two positions and 12 held three or four positions. At the cen-tre there were four individuals, led by the village head, who between them held a total of 29 offices. In spite of their power, however, they had little autono-my, and the head strictly enforced de-crees and policies determined from above, visiting Majalaya almost daily to meet with government agencies on this or that policy or decision. It was a typi-cal New Order village (for other good village studies, see Hart 1986; Hardjono 1987; Hüsken 1988; Schweizer 1989; Warren 1993; Cederroth 1995; and Su-wondo 1997).

How much of this has changed today, with the implementation of Law 22/ 1999 and the introduction of the BPD? The Bandung district government passed the implementing regulations on village governance quite early, in May– June 2000. The two decrees on the BPD

(relating to elections and functions) are fairly straightforward and in line with Law 22 and Kepmen 64. Candidates for the BPD can be proposed by individu-als or organisations, and all residents 18 years and older have the right to vote through universal and secret balloting. Sariendah is a large village (approxi-mately 10,000 people), so there are 13 members in the BPD. There were 25 can-didates who passed the eligibility screening and two who did not: criteria include completion of secondary educa-tion, that candidates have lived in the village for five years, and that they are ‘loyal and faithful to Pancasila and the 1945 Constitution’. Village head elec-tions have always been very competi-tive events, and so was the BPD election in 2000. Candidates campaigned in their home hamlets for votes, and posters were seen all around the village with photos of candidates. Some of the more energetic candidates provided meals and cigarettes to potential voters.

Voting took place on a Sunday in Sep-tember 2000, when people were off work, and most people voted—some 75%, according to official statistics. The voting process for the BPD was similar to that for national and village head elec-tions. The ballot paper had photos of the 25 candidates, and voters had to punch a hole for the candidate of their choice. The same polling stations were used as during the 1999 national general elec-tions, in 12 places around the village. No-one complained that voting was anything but free and fair. As is usually the case in local politics in Java, residence and family relations were im-portant determinants of voting behav-iour—when people talked about which candidate they supported, it was some-one whom they knew or who lived in their hamlet.

Of the 13 elected candidates, four were new to the village government,

while nine had some kind of previous experience. They had a variety of back-grounds: school teacher, religious leader, factory worker, entrepreneur, pensioner. Only one was a woman, and only two were younger than 30 years. The candidate with the most votes au-tomatically became chair. He is a prima-ry school teacher and son of a former popular village head, and also shares great-grandparents with the present head. The runner-up automatically be-came secretary. She too is a primary school teacher, but her popularity comes from the fact that she is the most respect-ed female Islamic teacher in Sariendah, holding several classes per week for women in different hamlets.

The BPD members were sworn in immediately, and have met twice per month during the initial two years. Kep-men 64/1999 requires BPDs to meet at least once a year, but the Sariendah members have taken their new task se-riously. The relationship of the BPD with the village government—the head and his staff—is fairly good. The Sariendah village head was elected after reformasi, in December 1999, and has proved his worth. He is energetic, sympathetic and popular, and consults regularly with the BPD.

In February 2001, the BPD approved the village budget for 2001, drafted and submitted by the village head. The total budget was Rp 80 million ($8,000), com-pared with the Rp 8 million Sariendah received in the past. Rp 50 million comes from a block grant from the Bandung government, and the remainder from local revenues. The most important sources of local revenue are house-tax, charges for minibuses passing through the village and income from a new marketplace built in 2000 with Social Safety Net funds.12 Budget funds have been used for regular infrastructure de-velopment projects such as road and

rigation improvements, for the village office, and to build an office for the BPD, the first in the subdistrict. There has also been discussion about building a swim-ming pool, to attract students through compulsory swimming classes! This might seem extravagant, but the pool would be owned by the village, and rev-enues would go to the village budget. Not everyone is in favour of this pro-posal, however.

The BPD is now the main institution in the village. The LMD has disap-peared, and the LKDM exists in a re-vised form, as the LPMD, the Lembaga Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Desa, Vil-lage Community Empowerment Board (my emphasis). It is still incorporated into the state bureaucracy, but much more loosely: no longer can the Depart-ment of Home Affairs impose its pro-grams through its loyal clients. But the village government and BPD in Sari-endah still consult with the LPMD in carrying out development programs. The women’s equivalent, the PKK, is in a similar position: it exists as a quasi-independent organisation but, without the power to enforce policies from above, it does not play an important political role. The same is true of the Babinsa. Sariendah still has a soldier placed in the village, but his (informal and formal) authority is much less pro-nounced than in the past. Finally, Golkar has all but disappeared from Sariendah. It ran second in the 1999 elections, to everyone’s surprise (Antlöv 2003b), but the village government has respected the Habibie regulation that civil servants may not join political parties, and has not privileged Golkar. Parties per se are not very important actors in local poli-tics in Indonesia today, and Sariendah is no exception. This will possibly change during 2003–04, as the country moves towards the new national

elec-tion. There are no other political organ-isations in Sariendah, even though they are permitted by Law 22/1999. With the presence of the LPMD, there is some minimal degree of organisational diver-sity, and people in Sariendah seem to be satisfied by this.

In the past it was quite a comfortable task to be a village official, with privi-leged access to funds and power, and no checks and balances. It is different today. On the one hand, the officials are allocated an increased workload through decentralisation. On the other, they are being scrutinised by the BPD, and are therefore less able to profit from their positions. Candidates for the vil-lage headship can no longer be motivat-ed primarily by the economic benefits of office. There must be other rewards for village officials, such as esteem and popularity. The new head in Sariendah thus talks about his jasa (‘service-mind-edness’) and says that he is proud to rep-resent the village. In this way, a new type of village leader is being created, with greater popular support than in the past. But this is obviously something that will not change overnight, especial-ly in a society so characterised by pa-tronage.

One of the promises of democratic local governance is that government will become more attuned to the needs of local people and allocate funds to those who need them most (Manor 1998; Blair 2000; Cornwall and Gaventa 2001; Fung and Wright 2001). This has not yet hap-pened in Sariendah, as funds have been used mainly for village infrastructure projects, such as building the BPD of-fice. Some people are critical of the swimming pool plan: they cannot see how they would benefit. But the new market is appreciated; residents no long-er need to travel to dirty, crowded Maja-laya to do their daily shopping. And

there is hope that since more people are involved in decision making, budget allocations and public policies will bet-ter reflect popular aspirations. The great-er competition that politics entails increases the likelihood that the Sari-endah elite will seek political support from disadvantaged groups—diversify-ing the political arena and givgroups—diversify-ing great-er importance to pro-poor policies. The village head and his staff are no longer the only authorities in the village: there is a multiplicity of voices. With the new office, BPD members will be on call ev-ery day. Anyone can come to the office with a complaint or a suggestion. This is new: the former LMD was monopo-lised by the village government, and people knew it was of no use to protest against official corruption or abuse of power. It is too early yet to say whether the Sariendah BPD will manage to bal-ance the demands of the village head and those of people critical of his way of running the village, but the start has been promising.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS

The Indonesian government is search-ing for a new paradigm to empower vil-lagers, fight poverty and develop the countryside. Since it lacks the funds, the foreign backing and the institutional ap-paratus to support large-scale rural de-velopment interventions, solutions of this kind are probably on their way out. Rather, as far as we can read from pub-lic statements (since the government does not have a detailed plan for this), rural development will be pursued through decentralisation of power to the regions and provision of a transparent legal and political framework that will attract foreign and domestic capital. There are a number of factors that have a direct impact on how development

programs will be implemented in the future, and I would argue that these to-gether provide for a paradigmatic shift in rural development and village gov-ernance in Indonesia.

The first thing to notice is village au-tonomy. In the past, higher authorities could do more or less as they wanted with villages: the village head and LMD were not in a position to protest. The LKMD was the arm of the Department of Home Affairs in the village, control-ling the flow of resources and develop-ment projects. Other ministries had similar line agencies. During my field-work in Sariendah in 1986, for example, large parts of West Java were threatened by crop failure due to a locust invasion. The Department of Agriculture issued an instruction that farmers should use only three types of pesticide, those known to kill the locust. Through its dis-trict and subdisdis-trict branches this mea-sure was implemented in all villages and the bad harvest was averted. Today, with democracy and autonomy, it will be much more difficult for the govern-ment to use such ‘firm-hand’ policies.

There will be fewer uniform nation-wide programs, since local conditions vary greatly. No longer will Jakarta-based experts decide what is best for the country, and carry out the blueprints through the National Planning Board (Bappenas).13 The ‘one-size-fits-all’ ap-proach is of the past. This means that rural development programs will need to be designed modularly (rather than generically) so that they can take into account local conditions, social structure and traditional values. People are cher-ishing their norms, their ‘traditional wis-dom’ (kearifan lokal) and it may be more difficult in the future to introduce pro-grams such as family planning or secu-lar schooling that conflict with the values of particular regional

tions. (Unfortunately, this shift is also bringing about tendencies to intolerance and ethnic chauvinism.)

However, in spite of the far-reaching character of regional autonomy, it seems that in practice many rural development programs will remain under the author-ity of the central government. Govern-ment Regulation 25 of 2000 (PP 25/2000) details the functions of the central and provincial levels of government (by default leaving the functions not mentioned to district and municipal governments) and states explicitly that agricultural extension and various tech-nical standards remain under central government authority. Poverty allevia-tion per se is not mentioned in PP 25/2000, but a new national body for poverty alleviation has been established. Education and health care have been devolved to the districts, but their capa-city to manage these services may prove inadequate, which would allow the provincial government to resume re-sponsibility for them (Law 22/1999, paragraph 9.2).

Another important factor is the diminishing financial capacity of the central government. One direct conse-quence of fiscal devolution is that the centre will have less money to spend within all sectors of development. Add-ed to this are the severe financial con-straints resulting from the 1997–98 crisis and the cost of debt from the subsequent IMF rescue packages. In 2003–04, it is es-timated that the total funds allocated for development programs in the national budget (the dana pembangunan) will be less than the interest paid on domestic and international debt.14 We can there-fore expect that the central government will spend less on rural development than in the past. With fiscal devolution and a huge domestic and international debt, it cannot afford to do otherwise.

This is both good and bad. It is good for reasons already mentioned: it signals the end of the servitude of villages to the central government and unleashes long-suppressed creativity and innova-tion in the regions. It is bad because pov-erty is on the rise in Indonesia, and local governments have to date not been very successful in addressing issues of rural development. One example of the com-plex character of rural development and regional autonomy is Kutai Kertanega-ra in East Kalimantan, one of the richest districts in Indonesia, with large oil and timber resources. Amid much publicity, the district head (who is also chair of the Indonesian Association of District Heads, Apkasi) in early 2001 launched what he called the ‘One Billion Rupiah per Village Movement’ (Gerakan Desa Semilyar), promising to provide each village in the district with development projects worth Rp 1 billion ($100,000), an amount increased in 2002 to Rp 2 bil-lion! The movement’s promotion flyer states that villages, especially those in the interior, in the past received only limited support from district, province and central governments, even though resources raised in Kutai come mainly from natural resources located in the interior. (There are few industries in Kutai and almost no tourism.) These village funds are divided between economic enterprises, infrastructural de-velopment and human resources.

However, the program has been crit-icised. First, there are allegations that the district government is misusing or mis-allocating funds, and that the Gerakan Desa Semilyarwill unnecessarily enrich companies and agencies that are close to the upper echelons of the Kutai Kerta-negara government. But beyond these accusations, local community workers are also worried that so much money ‘dropped’ into a village will cause more

problems than it solves. Such an opin-ion is based on the somewhat bitter-sweet experience of the Social Safety Net programs of recent years. Even though some funds did reach the countryside and the poor, the ‘quick and dirty’ na-ture of these crash programs created corruption and dependence. If villages in the past at times could not even use Rp 10 or 15 million responsibly, how can they be expected to manage Rp 1 or 2 billion? And will the funds not merely create new forms of patronage and de-pendency?

In order for villages to become more autonomous and self-sustaining than in the past, Law 22/1999 allows them to raise their own revenues for local devel-opment projects determined by the BPD and the village head.15 In the past, vil-lages were dependent on a yearly block grant from the district government, in addition to whatever extra projects the village could get from various line min-istries. There were no real incentives for villages to be innovative—in fact, there were implicit disincentives, since local innovation might lead to unwanted questions higher up in the command chain. Today, however, there are provi-sions for village enterprises. These are specified in Kepmen 64/1999 as ‘Vil-lage-Owned Enterprises’ (Badan Usaha Milik Desa), and are legal entities un-der commercial law.

Around the country, this has led to much experimentation and innovation. The Sariendah government’s new mar-ket (run as a village-owned enterprise) and proposed swimming pool are exam-ples, and we see more and more of such local initiatives. In one village I visited just outside of Bukittinggi in West Sumatra, the village customary elders, organised within the revived customary association known as Ninik Mamak, collected Rp 6 million ($600) in the

vil-lage to purchase a pump that provides water to 40 hectares of land. This is a purely village initiative (murni dari ma-syarakat), as the elders proudly told me, without interference from higher au-thorities.

TOWARDS LOCAL DEMOCRACY AND VILLAGE AUTONOMY

Law 22/1999 on Local Governance has introduced the possibility of renewal and self-rule for village institutions that under the New Order were uniform, authoritarian, corrupt and often in dis-repute. It is an enormous task to rebuild democratic and autonomous communi-ties after decades of intervention and often harsh political control. We should not expect immediate results. It will take time before the governance structure becomes more equitable, meaning that the village government becomes disem-powered relative to the BPD. Neverthe-less, the new legislation has been greeted by villagers across the country as an ex-citing instrument for democratic revi-talisation of village leadership and self-government. The voices of villagers in running their community are being strengthened and diversified. A system of checks and balances has been intro-duced that counters the power of the village heads.

How present is the state in Indone-sian villages today? During the past few years there has emerged a real measure of local autonomy. The doctrine of mono-loyalitas has been abolished, so that Golkar no longer holds monopoly pow-er, and members of the local village elite are not required to support the govern-ment. Villages can resist proposed de-velopment projects and take decisions independently of higher authorities. In-stitutions can be adapted to local needs and wisdom. These are real and mean-ingful changes.

But there are threats.16 It is important to ensure that the BPD becomes a truly representative body and can maintain its present high level of credibility and au-thority. If the BPD is devalued (as the implementing regulations seem to indi-cate), the prospect of genuine village democracy is greatly weakened. BPDs in some parts of the country have ini-tially bowed to the traditional power of the executive. Members of councils need to be trained and empowered: they need to be reassured that, in the tightly knit village community, they will not be sub-ject to social or political sanctions by the executive or other members of the elite if they criticise village leaders.

However, the main threat to grass-roots democracy and village autonomy comes from outside the communities, from the state and from district elites. I am referring to the half-hearted mea-sures through which central and district governments support village autonomy, and the way local elites have captured the fruits of decentralisation. To what extent higher authorities will allow vil-lages to maintain their autonomy is still very uncertain. The army’s Babinsa are still present in most villages, even though they have become less power-ful. There is a wish to revise Law 22/1999;17 certainly there are powerful forces in Jakarta who would want to re-centralise and maintain control over the countryside. There is no guarantee that higher levels of government will sup-port the BPD vis-à-vis the village head. District governments will continue to want a loyal head and village govern-ment, and might therefore in the future continue to support the executive rath-er than the legislative branch.

Given this uncertain context, it is not sufficient merely to have laws support-ing democratisation and decentralisa-tion—there must also be clear policies

to include the disadvantaged. A roman-ticising of villages and communities might lead to a side-stepping of basic democratic principles. Concepts like ‘lo-cal wisdom’, ‘village autonomy’ and ‘customary values’ are often used naïve-ly—in fact such concepts could provide for highly patrimonial and authoritari-an government structures (Benda-Beckmann and Benda-(Benda-Beckmann 2001). If the quest for regional autonomy al-lows traditional and aristocratic elites to regain the authority they lost in the im-mediate post-independence period, this might not necessarily be conducive to democracy and pro-poor policies.

We do not yet know the future of lo-cal democracy and rural development in Indonesia. But fundamental changes in the leadership and institutional struc-ture of villages offer considerable hope that new local organisations will be built that can protect and articulate the peo-ple’s interests. This is why hundreds of thousands of villagers around the coun-try invest considerable time and energy in the BPDs. The changes are a major democratic breakthrough and have great potential to open up decision mak-ing and popular participation. As the brief discussion of the Sariendah case shows, villagers have more trust in the local government today than before de-centralisation, simply because it is per-forming better under scrutiny and supervision. It is much more difficult for village officials to be corrupt. More peo-ple are learning about democratic pro-cesses of decision making. There is hope that the village will be governed by peo-ple who are committed and well inten-tioned, rather than by the rent seekers of the past. This is good for rural devel-opment, and good for Indonesia.

NOTES

1 Zacharia (2000: ch. 3) provides a fuller discussion of these regulations.

2 1945 Constitution, section 4, paragraph 18, Elucidation, translated in Simor-angkir and Mang Reng Say (1980: 61–2). 3 James Scott has argued (1998: 2) that states need to make each community leg-ible in order to ‘get a handle on its sub-jects and their environment … Whatever their other purposes, the design of scien-tific forestry and agriculture and the lay-outs of plantations, collective farms, [Tanzanian] ujamaa villages, and [Viet-namese] strategic hamlets all seemed cal-culated to make the terrain, its product, and its workforce more legible—and hence manipulable—from above and from the center’.

4 Ketetapan MPR RI Nomor V/MPR/1983 tentang Pertanggung-jawaban Presiden Republik Indonesia Soeharto selaku Mandataris Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat serta Pengukuhan Pemberian Penghargaan sebagai Bapak Pembangu-nan Indonesia [MPR Decision No. V/ MPR/1983 on the Responsibilities of President Soeharto of the Republic of Indonesia as Mandated by the People’s Consultative Assembly and on the Be-stowal of the Title of Father of Indone-sian Development].

5 The LKMD was introduced in 1980 as the state’s vehicle for rural development (Schulte Nordholt 1987). It was the low-est level of a complex planning frame-work for national development. It was originally intended that villagers’ voices would be heard in the LKMD and forwarded upwards through the bureau-cracy. But the LKMD was not a demo-cratic institution, because its members were appointed by the village head, so it was soon captured by village elites to further their own interests. The LKMD rather became the main channel for lo-cal-level corruption, since development projects and their funds were routed through it.

6 Under Law 5/1979 village heads were elected. In fact, the system of village head elections has remained stable over a long period, at least on Java. It was

institution-alised by the Dutch colonial government, beginning in Central Java in the early 19th century. Some self-ruling govern-ments in the outer islands had elected heads, but the majority had hereditary leaders. In most cases, and certainly on Java, heads before 1979 were appointed or elected for life. But although under Law 5/1979 village heads were elected by universal suffrage, elections were tightly controlled by the government (Schulte Nordholt 1982; Keeler 1985; Kar-todirdjo 1992; Hüsken 1994; Antlöv 1995; Syahbudin Latief 2000). Because of the privileges that came with the office, elec-tions were highly competitive, in Java sometimes involving tens of thousands of dollars in campaign expenses (for one such case, see Hüsken 1994). Neverthe-less, through a compulsory screening process, authorities could weed out un-wanted candidates and, through intimi-dation and privileged treatment, ensure that the favoured candidate would win. 7 The subdistrict (kecamatan) is conspicu-ously absent in Law 22/1999 and its im-plementing regulations. It is mentioned only briefly in paragraph 1.m of the law, as the extended arm of the district gov-ernment [wilayah kerja Camat sebagai per-angkat Daerah Kabupaten dan Daerah Kota], with no autonomy.

8 Administrative villages (desa) exist only within districts (kabupaten) and not with-in municipalities (kota). Even though Law 22/1999 also covers kota, this does not concern us here, since urban communi-ties (kelurahan) are not regulated under the section on village governance—the

kelurahan have no autonomy and no dem-ocratic institutions, and remain under the firm authority of the subdistrict and municipal government (paragraph 1.n). In the past, there were some desa in cit-ies, but with Law 22 they have been con-verted to kelurahan (or should have been—this has been resisted in some ar-eas).

9 For a case study of the way such regula-tions have been implemented in West Sumatra, see Benda-Beckmann and Benda-Beckmann (2001).

10 These requirements are reminiscent of those in Law 5/1979; for instance, the candidate must not have been a member of the Indonesian Communist Party, must be loyal to Pancasila, and must be-lieve in God.

11 Both Kepmen 64/1999 and PP 76/2001 are available at www.gtzsfdm.or.id. 12 After the Asian financial crisis, the

gov-ernment replaced its regular develop-ment programs with so-called Social Safety Net projects, infusing cash into the countryside through a number of food-for-work projects, subsidised rice and public health care programs and micro-credit schemes (Daly and Fane 2002). 13 This has direct consequences for foreign

consultants and experts: their tasks will be more complex and localised but, it is hoped, also more in conformity with lo-cal conditions.

14 Personal communication, Sugeng Ba-hagijo, deputy director, International NGO Forum on Indonesian Develop-ment (INFID), 20/12/2002.

15 Villages are not mentioned in Law 25/ 1999 on the Fiscal Balance between Cen-tral and Local Governments, and this law need not concern us here.

16 I have discussed in a separate essay some of the challenges for village institutions in the coming years (Antlöv forthcom-ing). They include the resilience of the village elite, the absence of full central government support for village auto-nomy, and the lack of district–village fis-cal balance.

17 The latest development (June 2003) is that the Department of Home Affairs has again initiated the revision (the word used is penyempurnaan, lit. ‘perfecting’), aiming to submit the bill to the DPR in late 2003 and pass it before the 2004 na-tional election. At the time of writing, the content is not publicly known.

REFERENCES

Antlöv, Hans (1995), Exemplary Centre, Ad-ministrative Periphery: Rural Leadership and the New Order in Java, Curzon Press, Rich-mond, Surrey.

Antlöv, Hans (1999), ‘The New Rich and Cultural Tensions in Rural Java’, in Michael Pinches (ed.), Culture and Privi-lege in Capitalist Asia, Routledge, London: 188–207.

Antlöv, Hans (2003a), ‘Not Enough Politics: Power, Patronage and the Democratic Polity in Indonesia’, in Ed Aspinall and Greg Fealy (eds), Local Power and Politics in Indonesia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Antlöv, Hans (2003b), ‘National Elections, Local Issues: The 1997 and 1999 Elections in a Local Perspective’, in Hans Antlöv and Sven Cederroth (eds), Elections in Indonesia: The New Order and Beyond, Rou-tledgeCurzon, London.

Antlöv, Hans (forthcoming),’Village-Based Governance and Community Democracy on Indonesia’, in Anne Booth and Jona-than Riggs (eds), Decentralization and De-mocracy in Southeast Asia, NIAS Press, Copenhagen.

Benda-Beckmann, Frans, and Keebet von Benda-Beckmann (2001), ‘Recreating the Nagari: Decentralisation in West Su-matra’, Working Paper No. 31, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle.

Bennett, Chris (2002), ‘Responsibility, Ac-countability, and National Unity in Vil-lage Governance’, in Carol J. Pierce Colfer and Ida Aju Pradnja Resosudarmo (eds),

Which Way Forward? Forests, Policy and People in Indonesia, Resources for the Fu-ture Press, Washington DC, and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 60–80.

Blair, Harry (2000), ‘Participation and Ac-countability at the Periphery: Democratic Local Governance in Six Countries’, World Development 28 (1): 21–39.

Booth, Anne (1988), Agricultural Development in Indonesia, Allen and Unwin, Sydney. Breman, Jan (1980), The Village on Java and

the Early Colonial Period, Comparative Asian Studies Programme, Erasmus Uni-versity, Rotterdam.