Volume 5 Number 1 2008 www.wwwords.co.uk/ELEA

Conceptualising Quality E-learning in Higher Education

ABEL USORO & ABBAS ABID

University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT Both academic and non-academic institutions, such as businesses, have increasingly been interested in the use of information and communications technology (ICT) to support learning, otherwise termed e-learning. This interest has been fuelled by the new developments in ICT, such as multimedia and the Internet with its World Wide Web. Other incentives have been the associated (expected) reduction of the cost of education and the easier expansion of education to the increasing market that cannot be reached by traditional delivery. Especially with higher education, the issue of quality is raised, leading to both anecdotal and empirical evidence of ways to maintain quality while deriving the benefits of e-learning. This article discusses the issue of quality in higher education and examines how it can be maintained in online learning. Key current research is used to develop a conceptual framework of nine factors, which include content, delivery, technical provision (referred to as tangibles) and globalisation. Areas for further studies (including primary study to validate the framework) are highlighted.

Introduction

It is not yet possible to be conclusive about what constitutes quality in e-learning because it is only since the 1990s that the expansion in information and communications technology (ICT), especially the Internet, has motivated the explosion of research and practice in this field. Indeed, growth in technology has run at a faster pace than research and a full understanding of what should constitute quality in e-learning. Thus, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has yet to finalise framework standards for quality e-learning. Given this background, this article attempts to explore the concept of quality in learning by reviewing literature in higher education (HE) and e-learning. Based on this desk research, an attempt is made to identify common themes and to summarise what may be regarded as quality criteria in e-learning. Pointers are also offered to areas for further investigation.

Operational Definitions

Quality in Higher Education

The following change factors described by Green (1994) have fuelled the current interest in the quality of HE in developed countries:

• the rapid expansion of student numbers in the face of public expenditure worries; • the general mission for better public services;

• increasing competition within the educational ‘market’ for resources and students; • tension between efficiency and quality.

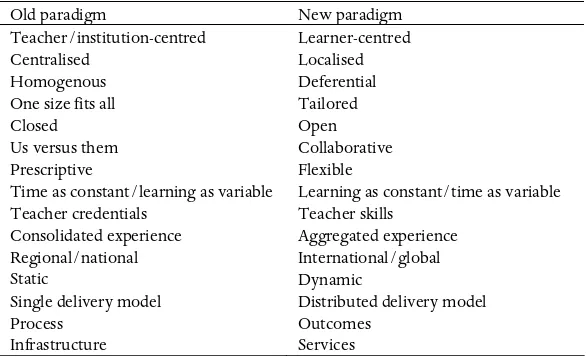

Granted that educational institutions are not pure business organisations that are swiftly changing with the environment, there have been some paradigm shifts in the concept of HE (Pond, 2002), as indicated in Table I.

Old paradigm New paradigm Teacher/institution-centred

Time as constant/learning as variable Teacher credentials

Learning as constant/time as variable Teacher skills

Table I. Old and new concepts for accreditation and quality assurance (adapted from Pond, 2002).

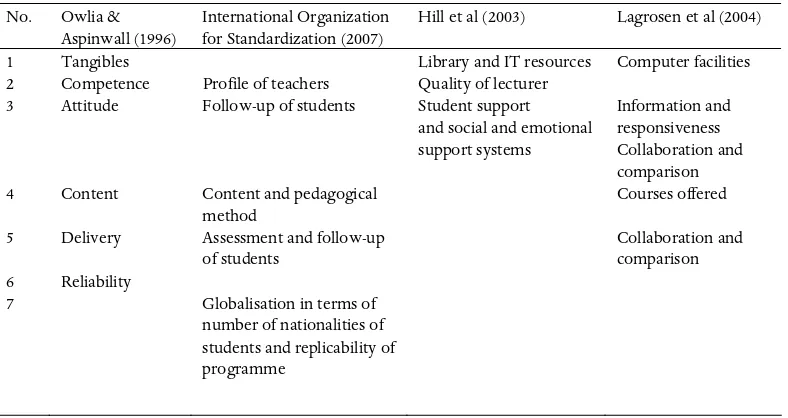

As Ellis et al (2007) state, quality for HE is a vexed term as it may suggest the notion of accountability at the expense of improvements. Yet, quality has to be conceptualised in order to improve it. HE belongs to the service rather than the manufacturing industry, which has more precise measures for quality. This has not discouraged attempts to conceptualise and even measure this concept in HE (cf. Harvey et al, 1992; Ashworth & Harvey, 1994). Owlia & Aspinwall (1996) studied earlier attempts and also quality frameworks in other disciplines, such as software engineering, which they argue are akin to HE. From their study they produced a conceptual framework that groups 30 attributes into the six dimensions of tangibles, competence, attitude, content, delivery and reliability (see Table II).

Owlia & Aspinwall’s (1996) research appears to be the most comprehensive dimensioning study of quality of HE. Other studies appear to confirm or complement some or all of the quality dimensions identified by Owlia & Aspinwall. Their study also recognises that quality is in the eye of the beholder. They argue that interests of stakeholders vary with the quality dimensions. For instance, while content and reliability are of interest to students, staff and employers, tangibles and competence are not of interest to employers; and attitude and delivery are of interest to students only.

The rest of this section will present a few additional studies and quality standards which can be seen to support Owlia & Aspinwall’s dimensions.

The ISO (2007) has defined their HE quality criteria as: • content and pedagogical method;

• achievements and impact of the programme demonstrated by performance indicators (number of students, number of nationalities, assessment and follow-up of students, profile of teachers, etc.);

• connection of the programme to business, governmental and other stakeholder groups; • replicability of the programme – whether it could be implemented elsewhere in the world; • visibility of the programme, in particular in the media.

No. Dimensions Characteristics

1 Tangibles Sufficient equipment/facilities Modern equipment/facilities Ease of access

Visually appealing environment

Support services (accommodation, sports, etc.) 2 Competence Sufficient (academic) staff

Theoretical knowledge, qualifications Practical knowledge

Up to date

Teaching expertise, communication 3 Attitude Understanding students’ needs

Willingness to help

Availability for guidance and advice Giving personal attention

Emotion, courtesy

4 Content Relevance of curriculum to the future jobs of students Effectiveness

Containing primary knowledge/skills Completeness, use of computer Communication skills and teamwork

Flexibility of knowledge, being cross-disciplinary 5 Delivery Effective presentation

Sequencing, timeliness

Table II. Quality dimensions in higher education by Owlia & Aspinwall (1996).

Hill et al (2003) are among the researchers who have examined quality from the perspective of students. They found the most influential quality factors in the provision of HE to be the quality of the lecturer and the student support systems. Their research was carried out with nursing, management studies, and learning and teaching students. Their main question was: ‘What does quality education mean to you?’ Other factors that emerged from their research were social/emotional support systems, and library and information technology (IT) resources.

Concentrating on the two most prominent factors, the quality of the lecturer requires the lecturer to know his/her subject, and to be well organised and interesting to listen to by being positive and enthusiastic. These requirements pertain to the delivery in the classroom. The relationship with students in the classroom adds to the quality of the lecturer. The relationship appreciated by the students has to be easy and helpful for learning. Andresen (2000) agrees with the importance of the quality of the lecturer. It is feared that large class sizes and the increasing use of e-learning and resource-based learning will detrimentally affect the required stimulating and enthusiastic environment between the lecturer and students (Gibbs, 2001). These fears necessitate quality assurance in e-learning environments.

Lagrosen et al (2004) are other researchers who have investigated quality from the perspective of students. After reviewing earlier studies of quality in HE, they used interviews and questionnaires to study 448 Austrian and Swedish students. Their study revealed the following factors as significant:

• courses offered; • computer facilities;

• information and responsiveness; • collaboration and comparison.

comprehensive measure of quality. Moreover, a factor that is most often ignored, given the regulatory and competitive demands, is the quality of the students. Although the achievement of entry qualifications, for example, the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT), has been shown to correlate positively with success in completion of education programmes, the increasing commercialisation of HE and increasing competition have led some institutions to lower or entirely remove the needed entry qualifications, with the result that weaker ‘inputs’ – students – are used with the aim of providing quality ‘outputs’ – graduates. This has great potential to weaken quality education (Wilson, 2007). The existence of such a weakening effect places great responsibility on increasing the quality (and perhaps quantity) of student support systems.

No. Owlia & Aspinwall (1996)

International Organization for Standardization (2007)

Hill et al (2003) Lagrosen et al (2004)

1 Tangibles Library and IT resources Computer facilities 2 Competence Profile of teachers Quality of lecturer

3 Attitude Follow-up of students Student support and social and emotional 4 Content Content and pedagogical

method

Courses offered

5 Delivery Assessment and follow-up of students

Collaboration and

comparison 6 Reliability

7 Globalisation in terms of number of nationalities of students and replicability of programme

Table III. Approximate mapping of various HE quality frameworks.

While it is more than a decade since the study was carried out, parts of Owlia & Aspinwall’s (1996) framework map to subsequent studies and views concerning the quality of HE, as shown in Table III.

We will see that the quality dimensions of HE appear in difference guises in various e-learning research, which will be presented below.

E-learning

Since the late 1990s, there has been tremendous interest shown in e-learning by practitioners and academics alike. E-learning is used to deliver training, education and collaboration using various electronic media but, predominantly, the Internet, whose tools have constituted the main driver of e-learning (cf. Fry, 2001). If well designed and managed, e-learning can overcome many barriers associated with traditional learning. These barriers include students’ tardiness, schedule conflicts, unavailable courses, geographical isolation, and demographic and economic disadvantage (Hijazi et al, 2003).

learning materials available to students and to coordinate their learning activities. In the UK, most of the successful e-learning programmes are the blended rather than the pure (no face-to-face contact) approach. Ennew & Fernandez-Young (2006) report on the failure of the flagship UK e-University (UKeU) project. This was launched in February 2000 with a government grant of £62 million and matching private sector funding from reputable sources like Fujitsu and Sun Microsystems (with a £5.6 million contribution). One of the agreed reasons for the failure is that the project was supply-led, predominantly driven by the technological possibilities, with little consideration of market research and market intelligence. Thus, recruitment was expected by the end of 2003 to be more than 5000 [1], whereas only 900 students were recruited by that date. This case study argues for the limitation, especially in the UK, of online learning as a complete substitute for more traditional forms of delivery. Ennew & Fernandez-Young (2006) also use the case study to argue for the need to avoid underestimating demand analysis in any major e-learning venture. They recommend that such a venture must focus not only on what technology can do, but also (and perhaps predominantly) on what customers want.

The argument as to whether learning is superior to facto-face learning is not settled, but e-learning has entered centre stage in today’s delivery of training and education, whether in industry or in educational institutions. Players in the e-learning field are varied and include content providers, technology vendors and service providers, and they target academic, corporate and consumer markets. The US Department of Labor projected an increase from US$550 million to US$11.4 billion in corporate e-learning revenues between 1998 and 2003; and this increase represents an 83% compound annual growth rate (Gunasekaran et al, 2002).

Pros and cons of e-learning. There are a number of reasons which make e-learning appealing to educational and non-educational institutions, as well as to learners. The wide acceptance and availability of the Internet means e-learning eliminates learning barriers of time, distance and socio-economic status, simultaneously allowing individuals to take more responsibility for their learning, which becomes lifelong. Students can access and benefit from a variety of experts and resources that may not be available locally. The fact that materials and delivery can be replicated easily and very economically is a strong appeal to HE, which seeks lower costs in the face of increased learning demands (Alexander, 2001; Antonucci & Cronin, 2001; Gunasekaran et al, 2002; Hijazi et al, 2003; Osborne & Oberski, 2004). The e-learning mode of educational and training delivery, along with its collaborative tools, can transform a non-learning organisation into a learning one, which is a very desirable attribute in the current global environment. A learning organisation has the additional advantage of boosting staff morale and motivation (Tarr, 1998).

There is also a change in the way books are now published. Authors provide plenty of electronic materials, which include extra examples, problems and solutions, animated simulations, user group and feedback systems, banks of test and exam questions with solutions, tools to compose exams and tests, and provision for lecturers to design their courses and customise material to their students. Lecturers also appreciate other tools that allow them to manage their students and their students’ learning experiences. The fact that these are all available on the Internet also means that lecturers have easier access to a variety of publications with their associated support materials.

Although not unanimously accepted, some research evidence points to the advantages of e-learning in terms of giving teachers access to more resources, it being an effective way to implement national curriculum and instruction standards, and produce better performing learners than the traditional approach (Larson & Bruning, 1996; McCollum, 1997). One such body of evidence emanates from the School of Computing at the University of the West of Scotland. As reported by Stansfield et al (2004), the academic performance in the postgraduate programmes run online is better by an average of 9% over the traditionally delivered versions. With regard to the workplace, Lain & Aston (2004) have documented surveys that report consistent worldwide training, reduced delivery-cycle times, increased learner convenience, reduced learner information overload, improved tracking and lower expenses, among others, as evidence of e-learning success.

• overly ambitious desired outcomes given the budget and time constraints;

• use of technologies without regard for appropriate learning design – focus is shifted from learning to technology, which should actually be an enabler of learning;

• failure to change learning assessment to match changed learning outcomes – except with careful planning and with simulated environments such as software development, there are some limits to which a learner can practically demonstrate his/her knowledge to the examiner;

• software development without adequate planning – e-learning software, like any other complicated and large software, needs adequate planning;

• failure to obtain copyright clearance, which may lead to legal problems with the owners of the copyrighted materials.

Other problems with e-learning include:

• initial costs may exceed the costs of traditional methods – computer hardware and software, as well as skilled personnel support, cost more than pen, paper and the chalkboard;

• more responsibility is placed on the learner, who has to be self-disciplined, especially in the pure e-learning mode where there is no face-to-face interaction;

• some learners have no access to a computer and/or the Internet, or the technology they use may be inadequate – this problem is very common in less developed environments, like Africa; • increased workload – for staff who have to develop specialised materials, sometimes with some

animation, which are well tuned to this non-traditional mode of delivery (Connolly & Stansfield, 2007);

• non-involvement in virtual communities may lead to loneliness, low self-esteem, isolation and low motivation to learn, and consequently low achievement and dropout (Rovai, 2002);

• dropout rates in e-learning programmes tend to be 10% to 20% higher than in traditional face-to-face programmes (Carr, 2000).

These problems bring the issue of quality in e-learning to the fore.

Quality in E-learning

We cannot begin to think about the quality of e-learning if we cannot convince a significant number of academic staff to take up the new technology in the first place. Despite the potentials of e-learning, a number of studies have identified the attitude of lecturers as a barrier to the acceptance of e-learning (Pajo & Wallace, 2001; Sellani & Harrington, 2002; Newton, 2003). From an analysis of earlier work in this area, followed by empirical study, Newton (2003) identifies the following barriers associated with lecturers:

• increased time commitment/workload (development time and delivery time); • lack of incentives or rewards;

• lack of strategic planning and vision;

• lack of support (training in technological developments and support for pedagogical aspects of developments);

• philosophical, epistemological and social objections.

These issues have to be sorted out to allow the free flow of quality e-learning. Besides lecturers, some potential students and employers are cautious of, and many national governments refuse to give full recognition to, e-learning qualifications (Ennew & Fernandez-Young, 2006, p. 150).

At the same time, effective quality strategies, initiatives and tools are very important for convincing lecturers and other stakeholders to adopt e-learning (Gunasekaran et al, 2002). Hart & Friesner (2004) have reported on the threat of plagiarism and poor academic practice to e-learning extension in HE, irrespective of country. The need to overcome this threat has to be recognised in a sound framework for quality e-learning in HE. Such confidence would go a long way towards building confidence in e-learning among stakeholders.

Since early 2006, the ISO has been developing a framework for standards to reduce the cost and complexity of adopting quality e-learning approaches and, at the same time, to facilitate the introduction of new e-learning products and services (Training Press Releases, 2006). The framework will introduce:

• a quality model to harmonise aspects of quality systems and their relationships;

• reference methods and metrics to harmonise methods used to manage and ensure quality in different contexts;

• a best practice and implementation guide to harmonise criteria for identification of best practice and guidelines for adaptation, implementation and usage of multi-pronged standards. The guide will also contain best practice examples.

Targeting individualised adaptability and accessibility in e-learning, education and training, the ISO (2007) is also currently developing an eight-part e-learning framework. The framework is meant to recognise the diverse approaches to the provision of e-learning and to establish some quality standards so as to bring comparability between the approaches and to reduce the cost and complexity of the development of quality e-learning tools. The quality standards that the ISO is developing will embrace every e-learning application scenario, for example, content and tool creation, service provision, learning and education, monitoring and evaluation, and life-cycle stages – ranging from continuous-needs analysis to ongoing optimisation.

The benchmarks provided by the US Institute (Gunasekaran et al, 2002, p. 48) for ensuring e-learning quality and evaluating HE effectiveness and policy include:

• a documented technology plan that includes password protection, encryption, back-up systems and reliable delivery;

• established standards for course development, design and delivery; • good facilitation of interaction and feedback;

• the application of specific standards for evaluation.

The key issues so far (and especially with the US Institute) seem to be the technology, including easy access, course content as evidenced in good course development and design, delivery, and good support systems. We will observe these issues being repeated in the remaining literature that is to be presented here.

While acknowledging the existence of useful tools, like Blackboard, for e-learning, Webb (2001, p. 74) considers the following non-technical issues in developing his online learning course: • Will the course be able to stand alone as a valid learning experience for the different student

profiles that will be exposed to it? It may be necessary to supplement it with non-electronic activities.

• Are the objectives, goals and assessment methods clear and compatible with e-learning format? • What remedial action will you take to care for non-performers in a timely fashion?

• How will mentoring and guidance be carried out?

• Beyond course completion, what will be the success criteria?

The framework proposed by Boticario & Gaudioso (2000, p. 121) comprises the following components:

• developing an interactive and online resource model which considers lecturers, students, tutors and other stakeholders at various levels – Blackboard is an example of e-learning software that allows different levels of entry to students, lecturers, tutors and system support;

• developing significant and active learning by stimulating student participation in the various learning resources, which is a challenge, given the absence of face-to-face contact;

• providing individualised communication to learners, who are also given individualised and quick access – using Blackboard as an example again, lecturers and tutors can send individualised communication (email) to students;

• developing a ‘community of practice’ with capability for knowledge sharing and collaboration among learners – such development may go beyond the formal learning to provision of informal facilities like a ‘chat room’.

• advance course requirements information; • close personal interaction;

• equivalent library materials and research opportunities; • equally rigorous assessment as in campus-based learning; • academic counselling and advice;

• the handling of plagiarism, authentication and online academic misconduct. In his contribution, Thomas (1997, p. 138) proposes the following key elements: • provision of learning materials;

• provision of facilities for practical work (for example, simulation); • enabling questions and discussions;

• assessment;

• provision of student support services (advising).

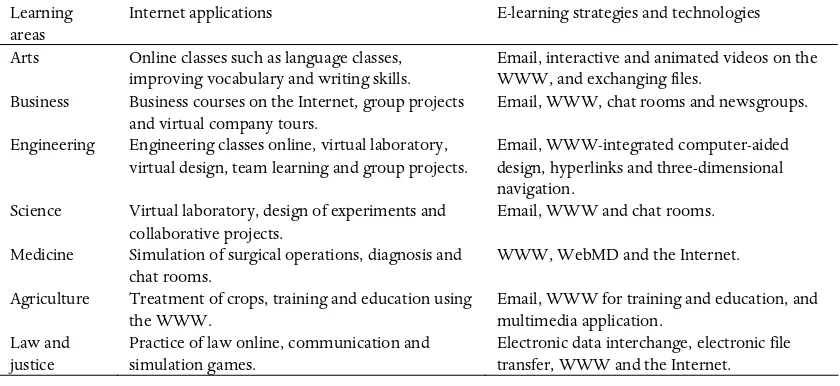

While there may exist general frameworks for quality e-learning, it has to be acknowledged that courses differ in their interactive and simulation requirements. The differences are well recognised in Gunasekaran et al’s (2002) proposal for implementing e-learning as shown in Table IV.

Learning areas

Internet applications E-learning strategies and technologies

Arts Online classes such as language classes, improving vocabulary and writing skills.

Email, interactive and animated videos on the WWW, and exchanging files.

Business Business courses on the Internet, group projects and virtual company tours.

Email, WWW, chat rooms and newsgroups. Engineering Engineering classes online, virtual laboratory,

virtual design, team learning and group projects.

Email, WWW-integrated computer-aided design, hyperlinks and three-dimensional navigation.

Science Virtual laboratory, design of experiments and collaborative projects.

Email, WWW and chat rooms. Medicine Simulation of surgical operations, diagnosis and

chat rooms.

WWW, WebMD and the Internet. Agriculture Treatment of crops, training and education using

the WWW.

Email, WWW for training and education, and multimedia application.

Law and justice

Practice of law online, communication and simulation games.

Electronic data interchange, electronic file transfer, WWW and the Internet. Table IV. Proposal for e-learning implementation (Gunasekaran et al, 2002).

Alexander (2001) complements existing work by tackling strategic issues and putting policies in place for faculty members involved in e-learning. His proposals can be summarised thus:

• development of a vision of e-learning;

• development of a technology development plan;

• development of faculty workload policies, which takes into consideration the demands of e-learning;

• maintenance of a reliable technology network;

• provision of a facility for technical support for both staff and students; • market research support;

• provision of time release for faculty members engaged in e-learning developments.

Zhao (2003) summarises existing research on quality of e-learning within his proposed framework, which has the following components:

• course effectiveness;

• adequacy of access in terms of technological infrastructure; • student satisfaction.

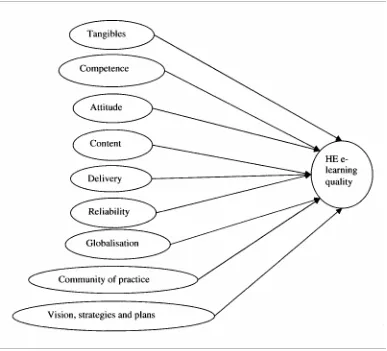

The various components of quality in e-learning that have been presented overlap each other. An amalgamation and normalisation of the components results in the following key factors (which are not necessarily arranged in order of importance):

1. tangibles: the technology that gives easy access with necessary security provisions, as well as a platform for opportunities such as an online library and research;

2. competence: capable technical support;

3. attitude: ensuring students’ satisfaction through appropriate interaction and feedback system (also entails mentoring, counselling, guidance and technical support);

4. content: effective course design and development that successfully achieve learning outcomes; 5. delivery: effective presentations that facilitate practical work (where necessary) by use of

simulation (for example); delivery that actively involves students at both group and individualised levels;

6. reliability: setting of evaluation standards and success criteria; equally rigorous assessment as in campus-based learning; handling of plagiarism, authentication and online academic misconduct – also, the use of market research to plan and test the outcome of e-learning;

7. globalisation: customisation of format for online delivery and ensuring language accessibility; 8. creating communities of practice: creating formal and informal communities for questions and

discussions;

9. developing e-learning vision, strategies, policies and plans: policies should include workload and time release to enable effective participation and development of e-learning activities. These key components (see Appendix for details of the amalgamation) are summarised in Figure 1.

The student experience with e-learning may be different from the traditional face-to-face delivery (Ennew & Fernandez-Young, 2006, p. 150), which creates concerns about less student stimulation with e-learning. However, there is no relenting in the efforts to animate and introduce interactivity in e-learning: scripting languages like Java and programming paradigms like Second Life (Cross et al, 2007) have been used. Also, it has been observed that the skills developed when playing computer games are useful for e-learning, and in some cases the same skills are the very objectives (for example, quick development of strategies in reaction to one’s environment) of learning (Gee, 2003). Thus, some research effort is directed at the application of computer games in e-learning. An example is provided in the work of Connolly & Stansfield (2007).

Areas for Further Research

The research initiated by this article is obviously work in progress. The mapping of the quality dimensions needs to be validated and refined by primary research so that an empirically tested framework can be presented for the introduction and management of e-learning in HE.

There is also another interesting area for further investigation: while e-learning promises to save time (because of the technological ease of replication, access to learning materials and communication), increased workload has been identified as a negative effect of taking up e-learning. Does e-learning save time for or take time off the lecturer? Are there intervening factors, such as phases in development, e-learning skills and the experience of the lecturer, which decide whether e-learning saves or consumes time?

Furthermore, considering Figure 1, it would be interesting to find out whether there are any relationships (and, if they exist, what the significance of such relationships is) between the proposed dimensions of e-learning on the one hand and the HE e-learning quality on the other.

It is proposed that paying adequate attention to these factors would help HE institutions to achieve high quality in e-learning. Nonetheless, future research will be required to test these factors empirically.

Summary and Conclusions

discipline makes it difficult yet to be conclusive on what constitutes, and what factors would enhance, quality in e-learning. However, without good quality e-learning, many financial and human resources will be wasted while the world is struggling to reach its teeming population with flexible and economically cheap education, such as e-learning has the potential to deliver.

Figure 1. Summary of dimensions of HE e-learning quality.

There are overlaps in existing research and initiatives towards conceptualising and dimensioning quality in HE as well as in e-learning. Drawing from secondary study and using Owlia & Aspinwall’s (1996) HE quality framework as the base, this article attempts to summarise the HE quality components into tangibles, competence, attitude, content, delivery and reliability. The components have been used as a basis to map research into dimensions of e-learning quality (see Appendix for full details). Additional components include globalisation, the creation of communities of practice, and the development of e-learning vision, strategies, policies and plans. Each dimension has been explained and used to develop the conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 1.

provisions and gain significant quality outputs. The framework as a whole will also help to evaluate an e-learning project as well as predict the output of e-learning even before its completion.

Developing and validating a comprehensive measure (which takes into consideration the varied perspectives of students, academics, employers and other stakeholders) will go a long way towards expanding the reach of HE into remote and otherwise not easily accessible populations.

Notes

[1] The original target was 12,600.

[2] The first eLearning Africa conference (http://www.elearning-africa.com/) was held in Ethiopia in 2006, the second in Kenya in 2007, and the third will be held in Ghana in 2008.

References

Alexander, S. (2001) E-learning Developments and Experiences, Education and Training, 43(4-5), 240-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00400910110399247

Alexander, S. & McKenzie, J. (1998) An Evaluation of Information Technology Projects in University Learning. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

Andresen, L.W. (2000) Teaching Development in Higher Education as Scholarly Practice: a reply to Rowland et al. ‘Turning Academics into Teachers?’, Teaching in Higher Education, 5(1), 23-31.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/135625100114939

Antonucci, R.V. & Cronin, J.M. (2001) Creating an Online University, Journal of Academic Librarianship, 27(1), 20-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-1333(00)00188-9

Ashworth, A. & Harvey, R.C. (1994) Assessing Quality in Further and Higher Education. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Boticario, J.G. & Gaudioso, E. (2000) Adaptive Web Site for Distance Learning, Campus-Wide Information Systems, 17(4), 120-128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10650740010350693

Carr, S. (2000) As Distance Education Comes of Age, the Challenge Is Keeping the Students, Chronicle of Higher Education, 46(23), A39-A41.

Connolly, T.M. & Stansfield, M. (2007) From E-learning to Games-based E-learning: using interactive technologies in teaching an IS course, International Journal of Information Technology and Management, 6(2-3), 188-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1504/IJITM.2007.014000

Cross, J., O’Driscoll, T. & Trondsen, E. (2007) Another Life: virtual worlds as tools for learning, eLearn Magazine, 3, 2. http://www.elearnmag.org/subpage.cfm?section=articles&article=44-1

Ellis, R.A., Jarkey, N., Mahony, M.J., Peat, M. & Sheely, S. (2007) Managing Quality Improvement of eLearning in a Large, Campus-based University, Quality Assurance in Education, 15(1), 9-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684880710723007

Ennew, C.T. & Fernandez-Young, A. (2006) Weapons of Mass Instruction? The Rhetoric and Reality of Online Learning, Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 24(2), 148-157.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02634500610654008

Fry, K. (2001) E-learning Markets and Providers: some issues and prospects, Education and Training, 43(4/5), 233-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005484

Gee, J.P. (2003) What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gibbs, P. (2001) Higher Education as a Market: a problem or solution? Studies in Higher Education, 26(1), 85-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070020030733

Green, D. (1994) What Is Quality in Higher Education? Concepts, Policy and Practice, in D. Green (Ed.) What Is Quality in Higher Education? 3-20. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Gunasekaran, A., McNeil, C.R. & Shaul, D. (2002) E-learning: research and applications, Industrial and Commercial Training, 34(2), 44-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00197850210417528

Hart, M. & Friesner, T. (2004) Plagiarism and Poor Academic Practice: a threat to the extension of e-learning in higher education? Electronic Journal of E-learning, 2(1), Paper 25.

http://www.ejel.org/volume-2/vol2-issue1/issue1-art25.htm

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) (2002) Information on Quality and Standards in Higher Education. Report 02/15. Bristol: HEFCE.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) (2005) HEFCE Strategy for E-learning. Bristol: HEFCE.

Hijazi, S., Prosper, B., Plaisent, M. & Maguiraga, L. (2003) Interactive Technology Impact on Quality Distance Education, Electronic Journal of E-learning, 1(1), 35-44.

http://www.ejel.org/volume-1-issue-1/issue1-art5-hajazi.pdf

Hill, Y., Lomas, L. & MacGregor, J. (2003) Students’ Perceptions of Quality in Higher Education, Quality Assurance in Education, 11(1), 15-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684880310462047

Indrus, N. (1999) Towards Quality Higher Education in Indonesia, Quality Assurance in Education, 7(3), 134-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684889910281566

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) (2007) ISO/IEC FDIS 24751. Geneva: ISO.

Lagrosen, S., Seyyed-Hashemi, R. & Leitner, M. (2004) Examination of the Dimensions of Quality in Higher Education, Quality Assurance in Education, 12(2), 61-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684880410536431 Lain, D. & Aston, J. (2004) Literature Review of Evidence of E-learning in the Workplace. Brighton: Institute for

Employment Studies.

Larson, M.R. & Bruning, R. (1996) Participant Perceptions of a Collaborative Satellite-based Mathematics Course, American Journal of Distance Education, 10(1), 6-22.

McCollum, K. (1997) A Professor Divides His Class in Two to Test Value of On-line Instruction, Chronicle of Higher Education, 43(24), A23.

Newton, R. (2003) Staff Attitudes to the Development and Delivery of E-learning, New Library World, 104(10), 412-425. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03074800310504357

Osborne, M. & Oberski, I. (2004) University Continuing Education: the role of communications and information technology, Journal of European Industrial Training, 28(5), 414-428.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090590410533099

Owlia, M.S. & Aspinwall, E.M. (1996) A Framework for the Dimensions of Quality in Higher Education, Quality Assurance in Education, 4(2), 12-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684889610116012

Pajo, K. & Wallace, C. (2001) Barriers to the Uptake of Web-based Technology by University Teachers, Journal of Distance Education, 16(1), 70-84.

Pond, W.K. (2002) Distributed Education in the 21st Century: implications for quality assurance, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 5(2).

http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer52/pond52.html

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) (2002) QAA External Review Process for Higher Education in England: operational description. Gloucester: QAA.

Rovai, A.P. (2002) Building Sense of Community at a Distance, International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 3(1). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/79/153

Sellani, R.J. & Harrington, W. (2002) Addressing Administrator/Faculty Conflict in an Academic Online Environment, Internet and Higher Education, 5, 131-145.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(02)00090-8

Stansfield, M., McLellan, E. & Connolly, T. (2004) Enhancing Student Performance in Online Learning and Traditional Face-to-face Class Delivery, Journal of Information Technology Education, 3, 173-188.

Tarr, M. (1998) Distance Learning: bringing out the best in training, Industrial and Commercial Training, 30(3), 104-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00197859810211251

Thomas, P. (1997) Teaching over the Internet: the future, Computing and Control Engineering Journal, 8(3), 136-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1049/cce:19970306

Training Press Releases (2006) ISO/IEC Standard Benchmarks Quality of E-learning. http://www.trainingpressreleases.com/newsstory.asp?NewsID=1767

Webb, J.P. (2001) Technology: a tool for the learning environment, Campus-Wide Information Systems, 18(2), 73-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/10650740110386143

Wilson, D.A. (2007) Tomorrow, Tomorrow and Tomorrow: the ‘silent’ pillar, Journal of Management Development, 26(1), 84-86.

APPENDIX

ABEL USORO is a lecturer in the School of Computing at the University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, United Kingdom. His research interest is information systems, including e-learning and knowledge management. He has widely published in refereed journals, such as Knowledge Management Research and Practice, and books, for example, Advanced Topics in Global Information Management: 1, edited by Felix Tan(IGI Publishing, 2002). He is a member of the British Computer Society, among others. He has chaired, organised and served on the scientific committees of many international conferences. Correspondence: Dr Abel Usoro, School of Computing, University of the West of Scotland, Paisley Campus, Paisley PA1 2BE, United Kingdom ([email protected]).