Milena I. Neshkova is assistant professor of public administration at Florida International University. Her research focuses on bureaucracy and democracy and how to achieve a more responsive, fair, and accountable public administration at both the domestic and international levels. Her work has been published in Public Administration Review, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, American Review of Public Administration, Governance, Policy Studies Journal, and Journal of European Public Policy.

E-mail: mneshkov@fi u.edu

Public Administration Review, Vol. 74, Iss. 1, pp. 64–74. © 2014 by The American Society for Public Administration. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12180.

Milena I. Neshkova

Florida International University

Allocation of public resources is an area in which considerations of both economic effi ciency and democratic legitimacy are likely to be present. Public administra-tors are often blamed for being too devoted to the norms of bureaucratic ethos, such as effi ciency, eff ectiveness, and top-down control, and less so to the norms of democratic ethos, such as inclusiveness and bottom-up decision making. Th is article examines whether manag-ers in agencies with greater budget autonomy are more likely to include the public when allocating resources. Because participation off ers an opportunity for agencies to enhance the legitimacy of their decisions, it is expected that the value of citizen input will increase with the degree of agency autonomy. Using data on the prac-tices of citizen participation in budgeting in two state departments—transportation and environment—this study fi nds that agencies with a higher degree of auton-omy tend to be more open to public comment than agen-cies with more centralized budget processes.

A

llocation of scarce public resources is an areain which considerations of both economic

effi ciency and democratic legitimacy are likely

to be present. Th ese confl icting incentives are even more

pronounced in a situation in which administrative agen-cies are delegated greater autonomy to perform their budget activities. Public administrators are often seen as being too devoted to the norms of bureaucratic ethos,

such as effi ciency, eff ectiveness, and top-down control,

and less so to the norms of democratic ethos, such as inclusiveness and bottom-up decision making (see Nabatchi 2010). To test whether this is the case, I study the incidence and practices of citizen involvement in the budget process at two state-level agencies—transporta-tion and environment—both

of which are relatively uniform across the United States.1 In other words, I examine whether managers in public agencies with greater autonomy in their budget activities are more likely to include the public when making allocation decisions.

Th e diversity in state budgeting practices off ers an

ideal situation to empirically test these confl icting motives in budgetary decision making. States diff er signifi cantly in the degree of centralization of their budget processes, the number of players involved, and the degree of openness to the public. For Rubin (2010, 84), one of the politically signifi cant char-acteristics of budget processes is their level of cen-tralization; she defi nes centralization as referring to the extent to which the budget process is bottom-up or top-down and the extent to which power is distributed among the participants. According to

the National Association of State Budget Offi cers

(NASBO), the power and restrictions placed on budget players aff ect the design of the budget process as well as funding decisions.

Because some agencies enjoy greater autonomy in the budget process, their managers face two main scenarios. On the one hand, independence from the

political bosses (such as the executive budget offi ce or

higher-level government) allows agency management to deploy a strictly technocratic process and allocate

program resources in the most effi cient way by just

relying on agency expertise and experience. Adding the incremental approach widely used by the states in budget development, it seems natural that agen-cies would rather invoke instrumental rationality and ignore time-consuming and expensive exercises such as public participation.

On the other hand, administrators face strong incen-tives to pursue more inclusive approaches, even at the

expense of effi ciency. First, there has been an

increas-ing number of regulations at the federal and state levels requiring the involvement of a broad array of stakeholders. Legislation such as the Intermodal Surface

Transportation Effi ciency Act

(ISTEA) of 1991 requires trans-portation agencies to provide citizens and other interested

Does Agency Autonomy Foster Public Participation?

I examine whether managers

in public agencies with greater

autonomy in their budget

activities are more likely to

include the public when making

competing funding claims but do so in a way that is consistent with the values of both bureaucratic and democratic ethos.

Budgeting is often viewed as a highly complicated task that is better handled by professional administrators who possess expert knowl-edge, technical skills, and years of experience. As Kweit and Kweit

write, “Th e ideal bureaucracy, described by Max Weber, relies on the

expertise as a means to achieve effi ciency” (1984, 235). Nabatchi

contends that public administration has long embraced bureaucratic

ethos and that operational values of effi ciency, effi cacy, expertise,

loyalty, and accountability have dominated the practice of public administration. She argues that these values have been present since the fi rst days of the fi eld and still “guide the modern practice of public administration” (2010, 382). Within this paradigm, adminis-tration of public policies, including budgeting, is considered a

profes-sional pursuit requiring expertise to be executed in an effi cient and

eff ective way. Moreover, bureaucracy is thought to derive its legiti-macy as a policy maker from its expertise (Dahl 1989; Stivers 1990).

Th e norms of democratic ethos require that public policies refl ect

public preferences. In the budget area, this requirement means that the spending priorities of governments should follow taxpayers’ wishes. One way to ensure that public preferences are considered by administration is to include public repre-sentatives in the decision-making process. For Rubin, “a key element in the design of budget processes is the degree to which the public has access to the process, through participation in planning, direct access and access through the media to useful information, and the chance to testify at hearings” (2010, 88). Budget processes vary in their openness to the public. Open budget processes invite participation from the broader public

and interest groups and allow diverse views and suggestions. Th ey

are considered more accountable to the public but also more vulner-able to infl uences from special interests. In addition, open budget processes are more likely when there is abundance of resources, as taking into consideration the claims of various interest groups tends

to increase the expenditure side (Rubin 2010). Th e opposite applies

to closed budget processes.

Citizens, however, lack specialized policy knowledge or budget

expertise. Th ey might even be reluctant to devote time and eff ort to

understand the policy implications of budget options or learn the

language of fi nancial management. Th e chronic low attendance at

public hearings is an indication of such reluctance on the part of the public. Besides the cost imposed on participants, there are also administrative costs associated with public participation (Ebdon and Franklin 2006; Irvin and Stansbury 2004; Robbins, Simonsen,

and Feldman 2008; Th omas 1995). Participation has the

poten-tial to slow down decision making because the public needs to be informed and even educated fi rst in order to meaningfully partici-pate in the budget process. Organizing public forums is a resource-consuming exercise in terms of both time and money. As Irvin and Stansbury put it, “the per-decision cost of citizen participation groups is arguably more expensive than the decision making done by a single administrator” (2004, 58) with the appropriate expertise

and experience. Th ere are concerns that administrators might lose

control over the process (Kweit and Kweit 1984; Moynihan 2003) parties “with a reasonable opportunity to comment on the proposed

program.” Th e federal mandates introduced under ISTEA were

reinforced by the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, which passed in the late 1990s and required the development of statewide public participation programs. Acts such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) have even broader reach, cutting across various departments and projects. Under NEPA, agencies are required to encourage and facilitate public involvement in all deci-sions that aff ect the quality of the human environment. Although the number of legal mandates for public inclusion has risen in recent decades, legislation has left to the discretion of public manag-ers both the choice of participation mechanisms and the extent to which public comment is considered in fi nal decisions. Given that fl exibility, administrators can either actively seek citizen involvement in order to achieve genuine public participation (Arnstein 1969) or opt for some superfi cial approaches to formally meet the require-ments for public inclusion. Second, being an unelected branch of government, bureaucrats are often blamed for being unresponsive to

citizens. Th us, the inclusion of the public in administration might

serve important bureaucratic values, such as achieving greater legiti-macy of administrative decisions and ensuring the support of critical constituency (Carpenter 2001; Meier 2000).

Th e following section discusses the incentives

for ensuring both economic effi ciency and

democratic legitimacy in the process of public budgeting. Drawing on the extant litera-ture on participation in the budget process, I develop two competing expectations about the eff ect of budget autonomy on an agency’s

degree of openness to public comment. Th en, I discuss the practices

of state budgeting and how various constellations aff ect the level

of fi nancial discretion of administrative agencies. Th e next section

describes the data and develops a model to test whether state depart-ments that enjoy greater autonomy in their budget process are more likely to invest in public participation as a potential way to enhance the legitimacy of their decisions. I then present the results of the

models and discuss their implications. Th e last section concludes

and outlines possible avenues for future research.

Competing Incentives in the Budget Process

Competing considerations are likely to be present when public managers allocate public monies: the budget process involves sorting out competing claims for limited public resources, and thus there are inherent trade-off s. To put it another way, budgeting determines which programs will be funded and to what extent, and as such, it inevitably makes winners and losers of some policy constituents. Moreover, the allocation decisions should square with compet-ing values within the public managers’ realm, values comcompet-ing from

both bureaucratic and democratic ethos. Th e process should be

concluded at a minimal cost, as required by the values of effi ciency

and bureaucratic rationality, and should refl ect public preferences, as required by the values of democratic governance. Supposedly, with public input, agencies’ allocation decisions would better refl ect citizen preferences. As Anderson and Smirnova (2006) note, public budgeting is simultaneously an economic instrument that is used for fi nancial planning purposes and a political instrument that should refl ect the particularities of the political environment. In sum, during the process of public budgeting, managers need to tackle

One way to ensure that public

preferences are considered by

administration is to include

public representatives in the

Indeed, when an agency enjoys greater autonomy, its managers face strong incentives to go beyond the values of bureaucratic ethos. Administrators will be strongly motivated to reach out to the public as a means to validate their decisions in terms of both practicality and legitimacy. Involving the public can also increase compliance with rules and regulations. Nabatchi (2010) argues that citizen participation is associated with various types of benefi ts: (1) norma-tive (or intrinsic) benefi ts, meaning that it has value in and of itself, regardless of outcomes; (2) instrumental benefi ts for citizens, that is, educational and empowering eff ects through increased knowl-edge of the policy process and the development of citizenship skills and dispositions; (3) instrumental benefi ts for communities, such as capacity building within the community; and (4) instrumental benefi ts for policy and governance. In a study on participatory budgeting, Ebdon and Franklin (2006) point out that the benefi ts from participation range from sharing information with the public and educating citizens about budget complexity to gaining input for administrative decision making and enhancing the public’s trust in government. Engaging citizens in the resource-allocation process might alleviate antigovernment sentiment and cynicism among citizens (Berman 1997; Ebdon and Franklin 2006) and help citizens develop greater appreciation for the job of public administrators (Ho and Coates 2006).

Extant research also relates public participation to better policy outcomes (Fung 2004; Fung and Wright 2001; Guo and Neshkova 2013; Moynihan 2003; Neshkova and Guo 2012; Roberts 1997;

Sirianni 2009). Citizens possess practical knowledge and local experience and thus can provide public managers with context-specifi c information that might not otherwise be available. Fung argues that the diversity of policy environments requires the use of context-specifi c means to achieve broad public

goals: “Such variation makes it diffi cult for

a centralized body of experts or managers to accurately specify a uniform asset of tasks or procedures that will eff ectively advance even the most general of public ends” (2004, 18). Based on their local knowledge, citizens can also warn administrators about some unintended consequences of policy decisions and thus prevent costly errors. Moreover, citizens can off er “innovative solutions to public problems that would have not emerged from traditional modes of decision making” (Moynihan 2003, 174; see also Fung and Wright 2001 for an earlier version of this argument). Broad public support for agency actions also means greater societal acceptance of administrative decisions.

In sum, there are two competing hypotheses about the behavior of public managers in agencies with more autonomous budget

proc-esses. Th e fi rst hypothesis expects that when given greater discretion,

administrators will be more likely to rely on the traditional modus operandi and their technocratic expertise rather than seek citizen input on budget issues. A contrary perspective, derived from the par-ticipatory budgeting literature, expects that greater discretion comes with greater need for accountability, and thus administrators will be more likely to invite public comment as a means of increasing the legitimacy of agency actions and securing the support of critical con-stituency. In addition, involving the public can improve compliance rates and enhance the quality of administrative decision making.

and powerful interest groups might take over. Th e participatory

budgeting literature also warns that citizens who are most active often represent private interests that might be very diff erent from the broad public interest (Ebdon and Franklin 2004; Landre and Knuth 1993; Robbins, Simonsen, and Feldman 2008).

Budget Autonomy and Participation

Broadly defi ned, budget autonomy denotes the independence of a lower-level unit from higher-level authorities in determining its revenues and expenses. In the case of state and local governments, autonomy can only be understood in relative terms because their

budgets need to be approved by legislative bodies. Th e more

discre-tion is left to governments in the budget process, the more control they have when performing various budgetary activities.

Given the long-standing reliance of public administrators on the values of technical rationality and the presence of various costs associated with public participation, it seems likely that managers in agencies with greater budget autonomy would rather rely on their own expertise to decide on how to allocate public resources than wait for citizens to reveal their spending preferences in the resource-consuming process of public participation.

On the contrary, the literature on participatory budgeting at the local level clearly associates the degree of budget autonomy with public participation (e.g., Fung and Wright 2001; Krenjova and Raudla 2013; Santos 1998). On the one hand, fi scal autonomy is viewed as an enabling condition that

facili-tates the process of participation. As Krenjova and Raudla contend, a certain degree of autonomy is needed “in order to make any form of PB [participatory budgeting] con-ceivable” (2013, 27). Clearly, governments with more self-generated revenue will have greater amounts for discretionary spending compared to governments that rely more on external transfers, which often have restraints

attached to them. Describing in detail the participatory budgeting experiment in the city of Porto Alegre in Brazil, Santos points out that “[g]iven the dependence of the municipal budget on federal transfers, an exogenously generated fi scal crisis may endanger the sustainability of the PB by undermining its capacity to deliver in a context of growing popular demands and expectations” (1998, 506). A study drawing on data from German municipalities fi nds that people are more likely to participate and have greater demands

for effi ciency in service provision if local governments enjoy greater

fi scal autonomy, measured as the amount of generated own-source revenues (Geys, Heinemann, and Kalb 2010).

On the other hand, the participatory budgeting literature stresses the need for political will on the part of the government to open space for public participation (Baiocchi 2003; Fung and Wright 2001; Postigo 2011; Santos 1998). If budget autonomy creates the possibil-ity for such space, public managers play an important role in making participation happen. Santos (1998) emphasizes the willingness of municipal administration to cogovern with the communities in the case of Porto Alegre. In her book on municipal budgeting, Rubin

(1998) observes that during the last few decades, public offi cials have

generally become more open to citizen input in the budget process.

Citizens possess practical

knowledge and local experience

and thus can provide public

managers with context-specifi c

funding varies over time and often comes with restrictions on how the monies can be spent. In sum, state agencies diff er considerably in their budgetary practices, and various constellations aff ect the amount of spending discretion and control exercised by agencies.

Methodology Data

Th e study utilizes both subjective and objective data from two

state-level agencies—departments of transportation (DOTs) and

depart-ments of environmental protection3 across all 50 states. Th e survey

data used here were collected as part of the 2005 Government

Performance Project (GPP).4 Th e project started in 1998 with the

main objective to assess the performance of states.5 Besides overall

state governments, the project surveyed several state agencies. An

online questionnaire was sent to state offi cials, administrators, and

managers.6 Th e data on citizen input were collected within the

fi nancial management section of the survey. Specifi cally, the data come from a subsection seeking information on whether the state/ agency provides opportunities for public input in the budget

proc-ess. Th e survey asks administrators to identify the strategies used by

their agencies to generate input from citizens about spending

priori-ties, budget development, and assessment.7 Th e survey responders

are given a matrix in which the rows are various participatory strate-gies, including citizen surveys, budget simulations, focus groups, open forums, public hearings, citizen advisory boards, and

tel-ephone hotlines. Th ere is an option to write in a strategy that is not

included on the list. Survey respondents are asked to select the strat-egies used by their agencies in relation to their usefulness in advanc-ing the outcomes of the four stages of the budget process (given in

the columns),8 namely, (1) information sharing, (2) budget

discus-sion, (3) budget decidiscus-sion, and (4) program assessment. Specifi cally, for the fi rst stage, respondents are invited to identify each strategy that “has advanced information sharing between citizens and agency

offi cials.” For the second stage, they need to mark each strategy

that “has advanced budget deliberations and discussions of budget

trade-off s between citizens and agency offi cials.” For the third stage,

the survey inquires about strategies that have “provided information

that agency offi cials use to make budget decisions.” For the last stage

of the budget process, the administrators need to select each strategy

that “has provided information that agency offi cials use to assess

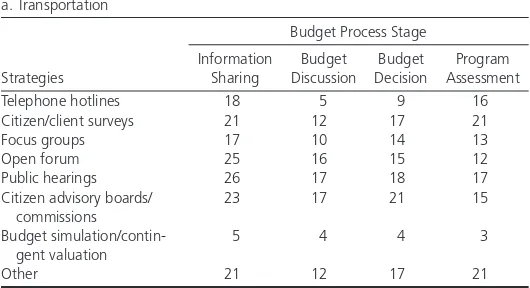

program results.” Table 1 shows the number of strategies found useful by respondents at each stage of the budget process by agency type.

Th e GPP survey also collected information on the relative

auton-omy of state departments in performing their budgeting activities, such as allotment control, forecasting authority, and development

of multiyear plans.9 For each activity, responders can choose the

level of responsibility of their agency versus the state’s executive

budget offi ce. Th e categories include primarily an executive budget

offi ce responsibility; 75 percent executive budget offi ce and 25

percent agency responsibility; responsibility shared about equally;

25 percent executive budget offi ce and 75 percent agency

respon-sibility; and primarily agency responsibility. Th e GPP survey was

sent to both state DOTs and state environmental agencies in the same year, and each agency was asked to respond to all parts of the survey, including the citizen input section and the section about

its relative autonomy from the state budget offi ce in performing

budgeting activities. States that provided valid answers to both Budgeting in the States

Public budgeting at the state level exhibits some unique char-acteristics that make it diff erent from both the federal and local levels. Comparing the levels of government and power distribution

between the executive and legislature, Th urmaier observes that

“[r]elative executive infl uence ranges from formidable executive dominance of the process at the local-government level to a more equalized level of infl uence at the national level, with state-level budgeting in between depending on the budget process and the line-item veto powers of the governors” (1995, 449). Governors commonly have stronger veto power than the U.S. president, as they can veto parts of a bill instead of just accepting or rejecting a bill in its entirety. Forty-three state governors have line-item vetoes that allow them to block any expenses they disagree with that are

listed as a separate line in the budget. Th irty-fi ve governors have the

power to strike the budget of an entire program or agency (for an in-depth discussion on how chief executives use their veto power, see Abney and Lauth 1985; Rubin 2010).

Th e structure of the budget process also varies signifi cantly from

state to state. It depends on the level of centralization of budget development, power distribution between the branches of govern-ment, and degree of openness of decision making to the public (Rubin 2010). In most states, the governor dominates the budget process, while in others, power is more balanced between the

executive and legislative branches. Th ere are few states in which the

legislature is given signifi cant power over the budget formulation. Yet scholars of budget politics agree that the executive branch tends to dominate state budgeting at the expense of the legislative branch

(Rubin 2010; Th urmaier 1995). In fact, the executive budget

move-ment of the twentieth century mostly aimed at strengthening the powers of governors (Clynch and Lauth 2006).

Th e budget cycle generally begins when agencies are called to submit

their requests for funding to the governor in accordance with his or her guidelines and recommendations. Upon receipt, the executive

budget offi ce reviews the proposals and meets with agency heads to

clarify the requests.2 Legally, the executive budgets are the fi nancial

plans of the chief executives, and thus they should refl ect the gover-nor’s programmatic and political priorities. Governors can also modify

departmental requests after an initial review of their budget offi ces.

Evidence shows that governors trust state budget offi ces and adopt 95

percent of their funding recommendations (Th urmaier 1995).

Executive budget offi ces are tasked with various functions, such as

developing revenue forecasts, caseload projections, predictions of state business activities (NASBO 2008). Administrative agencies, in turn,

have varying degrees of autonomy from the executive budget offi ce in

both the development and implementation phases of the budget proc-ess. Rubin (2010) identifi es two types of budget processes: bottom-up and top-down. In its most extreme form, top-down budgeting virtually ignores bureau heads, and agencies lack any autonomy in

the budget process. “Th e chief executive may not ask bureau chiefs

developed by the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). IAP2 ranks participation processes into fi ve stages of “increasing level of public impact”: inform, consult, involve,

col-laborate, and empower. Th e seven strategies listed in the GPP survey

question fi t into the three middle stages of the IAP2 classifi cation.

Telephone hotlines and citizen surveys are categorized as processes

that seek to consult the public. Th e participatory mechanisms at

this stage aim to “obtain public feedback on analysis, alternatives and/or decisions” (IAP2 2007). Yet telephone hotlines require less eff ort from administrators than surveys because citizens initiate the

“input” process by calling the agency. Th erefore, telephone hotlines

assume a weight of 1. With citizen surveys (coded as 2), administra-tors need to initiate the process by designing and sending out the questionnaires.

Focus groups, open forums, public hearings, and budget simulations

with citizens can be classifi ed as processes that aim to involve the

public. According to IAP2 (2007), at this stage, administrators seek “to work directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered.” Clearly, mechanisms involving two-way communica-tion allow for better understanding of public preferences: citizens get to discuss policy issues with professional administrators and sort out competing claims (Kathlene and Martin 1991; King, Feltey, and

Susel 1998; Robbins, Simonsen, and Feldman 2008; Th omas 1995).

In terms of weight, focus groups, open forums, and public hearings carry equal weight (coded as 3). Budget simulation exercises are assigned a higher weight (coded as 4) because they not only employ two-way communication but also make citizens aware of budget intricacies and trade-off s, and as such, they contribute to more informed decisions on the part of citizens (Ebdon and Franklin 2004).

Finally, citizen advisory boards or commissions are coded as

proc-esses that collaborate with the public, and they are assigned the

highest weight (coded as 5) among the participatory mechanisms

considered. Th e processes at this stage seek to “partner with the

public in each aspect of the decision including the development of alternatives and the identifi cation of the preferred solution” (IAP2 2007). Although citizen advisory boards can be very formal and ineff ective, research shows that members are likely to develop extensive knowledge on policy issues and understand the multiplic-ity of budget constraints and trade-off s faced by governments when allocating scarce resources (Robbins, Simonsen, and Feldman 2008).

For both indices, higher values are associated with greater use of citizen input strategies by administrators in the budget process.

Th e additive index ranges from 0 to 25, with a mean of 9.5

strate-gies per agency, while the range for the weighted index is from 0 to 109, with a mean of 42.26. Also, the data show that, on average, state DOTs employ a greater number of strategies compared to state

environmental agencies: 10.54 and 8.46, respectively.10

Admittedly, there are several drawbacks of these indices as measures of citizen input. First, they refer to the quantity of strategies rather than to their quality; the indices do not refl ect the substantive value of public comment or its practical applicability. Second, they do not account for the intensity of use for diff erent strategies: the survey questions constitute the cases used for this analysis. Specifi cally, 39

states provided information on their citizen participation practices (78 percent response rate), and 38 states responded to the questions about their autonomy in performing budgeting activities (76 per-cent response rate). Yet some of the states that responded to the par-ticipation question failed to provide data on the autonomy question, and vice versa, causing a drop in the number of useful observations

to 55 in the models using survey data. Th e study also utilizes data

available from the National Association of State Budget Offi cers, the

Environmental Council of the States, and other sources.

Dependent Variables

Th e dependent variables in this study are the measures of citizen

input, operationalized through two sets of indices based on the citizen participation practices provided in the GPP survey responses.

Th e fi rst index is additive, and each strategy for collecting citizen

input assumes the same weight. Th e strategies from all four budget

stages are summed. In this way, each state agency receives an index score for the whole budget process. Because there is no perfect method for obtaining citizen input (see, e.g., Ebdon and Franklin 2004; Robbins, Simonsen, and Feldman 2008), public agencies are advised to employ a variety of methods. As Ebdon and Franklin argue, “Governments using more than one method on a regular basis might be more likely to attain eff ective participation by off set-ting the weaknesses of one method with the advantages of another”

(2004, 35). Th us, summing the strategies for collecting citizen input

can serve as a useful proxy for the agencies’ outreach eff orts.

To construct the second index, each participatory strategy is given a diff erent weight based on the spectrum of public participation

Table 1 Number of State Agencies Utilizing Citizen Participation Strategies a. Transportation

Telephone hotlines 18 5 9 16

Citizen/client surveys 21 12 17 21

Focus groups 17 10 14 13

Open forum 25 16 15 12

Public hearings 26 17 18 17

Citizen advisory boards/

Note: The total number of responding state transportation agencies is 39.

b. Environment

Telephone hotlines 18 2 6 14

Citizen/client surveys 11 3 10 14

Focus groups 16 7 13 19

Open forum 17 6 13 20

Public hearings 19 8 16 20

Citizen advisory boards/

commissions 23 10 17 20

Budget simulation/

contingent valuation 4 3 4 11

Other 9 4 5 11

responsibility of the budget offi ce, then the variable is coded as –1. Budget autonomy takes a value of 0 if responsibility for allotment control or spending forecasts is shared about equally between the

agency and the executive budget offi ce. A value of 1 is assigned if

the particular budget activity is 75 percent agency responsibility. Finally, a value of 2 is assigned when the activity is primarily agency responsibility. Presented as percentages, the agencies forming the sample of this study have, on average, 56.6 percent of responsibility for allotment control and 97.3 percent of responsibility for develop-ing spenddevelop-ing forecasts. Transportation agencies enjoy, on average, slightly greater allotment autonomy (61.8 percent) than

environ-mental agencies (51.3 percent). Th ere is practically no diff erence

in the rate of forecasting autonomy between the two types of state agencies—96.7 percent for transportation and 97.9 percent for environmental agencies.

Th e third measure of budget autonomy is the percentage of

an agency’s own-source revenues (Own Source Revenue), which

refl ects the independence of state agencies from the federal gov-ernment. Because intergovernmental transfers often come with strings attached, they place limits on state-level agency autonomy. Moreover, the amount of federal aid varies over time, making this source of revenue less predictable and controllable. In the realm of funding diversifi cation, it is crucial for agencies to have greater resource independence. Own-source revenues of agencies come

from taxes, fees, service charges, permits, and licenses. Th us, the

more funds an agency generates on its own, the greater the level

of its spending discretion.13 Th e variable is calculated by

subtract-ing all federal aid. Th e data on the amount of intergovernmental

question only inquires whether a certain strategy has been used but

not how often. Th ird, the weighting mechanism ranks the strategies

in terms of their expected impact, but it does not take into account how well they were implemented in practice. Although limited, the indices provide valuable insights about participatory practices at the state level and can serve as ordinal indicators of the degree of agency openness to the public.

Key Explanatory Variables

Th e key independent variables in this study are the measures of

budgetary autonomy. Th e term refers to the degree of agency

independence from the state executive budget offi ce or federal

government. Th e independence of administrative agencies is only

in relative terms, as their budgets need to be approved by the state

legislature and the budget offi ce. Th e states vary considerably

in their budgetary practices and the limits put on the agencies’ discretion. Such variation allows us to explore whether the degree of autonomy matters when public managers decide on the level of public participation.

I consider three measures of agency autonomy. Th e fi rst two come

from the GPP project and are more or less subjective, based on the perceptions of the survey respondents about the level of

responsibil-ity of their agencies in performing various budgeting activities. Th e

third measure, more objective, refl ects the percentage of an agency’s own-source revenue.

Th e fi rst two variables are related to specifi c budgeting activities

performed by agencies, namely, the power to allot agency funds (Allotment Control) and the authority to develop spending forecasts (Forecasting Autonomy).11 Th e measures refl ect the degree of agency

responsibility for these activities versus the executive budget offi ce.

Allotment refers to the portion of an appropriation (the dollar amount authorized by the legislature) that may be expended or encumbered during a given period (NASBO 2008). In most states, appropriations are not available for expenditure until they have been allotted. In other words, appropriations are made through budget bills and translated into spending authority through the allotment process. Moreover, expenditures cannot exceed allotments. An appropriation may be obligated up to a greater amount but may only be spent up to the allotted amount. Allotment control is an integral part of the budget process, and responsibility for it can rest

with either the executive budget offi ce or the agency leadership, thus

aff ecting the level of agency autonomy.12 Forecasting—an important

part of fi nancial planning—refers to the process of estimating the amount of infl ows and outfl ows of the organization based on cur-rent law and the amount that will be available to support operating

costs and capital outlays in the current and future fi scal years. Th e

authority to develop spending forecasts allows organizations to iden-tify the areas of future shortfalls and arrange their resources in a way that will account for such events. When done properly, forecasting can enhance fi scal stability and enable corrective actions as needed.

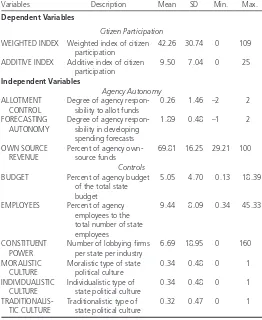

Both variables, Allotment Control and Forecasting Autonomy, are

operationalized on a fi ve-point scale ranging from –2 to +2, from minimal to relatively full autonomy. Table 2 provides descriptive sta-tistics for the variables used in the study. In terms of coding, if the

budget activity is primarily an executive budget offi ce responsibility,

then the variable is coded as –2. If the budget activity is 75 percent

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics for the Models

Variables Description Mean SD Min. Max.

Dependent Variables

Citizen Participation

WEIGHTED INDEX Weighted index of citizen participation

42.26 30.74 0 109

ADDITIVE INDEX Additive index of citizen participation

BUDGET Percent of agency budget of the total state budget

5.05 4.70 0.13 18.39

EMPLOYEES Percent of agency employees to the total number of state employees

9.44 8.09 0.34 45.33

CONSTITUENT POWER

Number of lobbying fi rms per state per industry

6.69 18.95 0 160

MORALISTIC CULTURE

from NASBO’s State Expenditure Reports of state governments, and environmental agencies’ budget fi gures come from a report of the Environmental Council of the States (2008).

Political environment can encourage the use of citizen input by

setting the expectations toward public managers. Th e signals

they receive regarding the role of citizens in government might be aff ected by the broader political culture in the particular state (Ebdon 2000 Elazar 1972; Lieske 1993; Lowery and Sigelman 1982). Elazar’s (1972) typology diff erentiates among three types of political subcultures: moralistic culture (found predominantly in the Northern states), individualistic culture (associated with middle parts of the country), and traditionalistic culture (refl ecting the attitudes and values of Southern states). Participation is greatly encouraged within the political traditions of moralistic states; individualistic states stress less participation, as they tend to regard government more as business; and traditionalistic states employ a paternalistic approach, within which only elites are expected to be active.

Previous research has tested the eff ect of political culture in the context of city governments (Ebdon 2000; Ebdon and Franklin 2006) and fi nds that political cultures do aff ect the level of partici-pation, with moralistic states having the highest citizen involve-ment, individualistic states having the lowest, and traditionalistic states falling in the middle. To control for the eff ect of political culture, I use three dichotomous variables derived from Elazar’s

typology: Moralistic Culture is coded as 1 for states with moralistic

political culture and 0 otherwise, Individualistic Culture has a value

of 1for states with individualistic political culture and 0 otherwise, and Traditionalistic Culture is coded 1 for states with traditionalistic political culture and 0 otherwise. To avoid perfect multicollinearity,

I exclude from the model Traditionalistic Culture, thus making it the

reference category.

Based on the participatory budgeting literature, I added a variable to control for the eff ect of the agency size. Prior research reports that agencies with greater manpower are more likely to invite

participa-tion (Wang 2001). Th e variable is operationalized as the

percent-age of percent-agency employees to the total number of state employees (Employees).

Estimation Routine

Two sets of models are estimated. An ordinary least squares regres-sion model is used to estimate the equation using the weighted

index of citizen input as the dependent variable. Th e weighting

mechanism makes the dependent variable an interval-level variable. When the additive citizen input is used as the dependent variable, a negative binomial regression model is estimated. Recall that the additive index is just the count of citizen input strategies used by each state agency. A negative binomial model is preferred when the assumptions of the Poisson distribution are violated and the mean and the variance are not equal. Because the density of the mecha-nisms used by public agencies to solicit citizen input does not meet the Poisson assumptions (the mean of the dependent variable is 9.5 and the variance is 49.55), I estimate a negative binomial model.

Finally, because it is unlikely that the observations within one state are independent, thus violating the independence assumption, the transfers for state DOTs come from NASBO’s State Expenditure

Reports. For environmental agencies, these data are available from

the Environmental Council of the States (2008). Th e agencies in

the sample have, on average, 69.8 percent of their revenues coming

from own sources.14 In contrast to the fi rst two variables,

environ-mental agencies have slightly greater revenue autonomy than DOTs: 70.9 percent and 68.8 percent, respectively.

It should be acknowledged that the three measures used here by no means capture all diff erent aspects of budget autonomy and represent only some of the possible operationalizations of such

variables.15 Th e fi rst two measures are perception-based and suff er

from all of the drawbacks associated with survey data. In addition, they refl ect particular budgetary activities rather than the whole budget process. Although not perfect, they are still useful proxies for the degree of agency budget responsibility vis-à-vis the state budget offi ce.

Controls

To isolate the eff ect of budgetary autonomy, I include a set of control variables in the models. Each control variable seeks to rule out a possible alternative explanation about the level of citizen input collected by administrative agencies.

As argued earlier, public participation in administration serves to ensure the support of agency stakeholders, making constituency power an important consideration when public managers decide

whether to involve the public and to what extent. Th e analysis of

Yang and Pandey (2007) on state-level health and human serv-ice agencies demonstrates the importance of clientele infl uence, recognizing that client groups can either support or undermine an agency’s mission (see also Meier 2000). From a similar perspective, a recent study by Handley and Howell-Moroney (2010) fi nds that the ordering of stakeholder relationships is a main predictor of how bureaucrats exercise their discretion regarding the extent of citizen

participation in administration. Th e authors argue that public

man-agers make a greater eff ort to include the public if they feel greater

accountability to citizens in the community. Th us, I expect that a

more powerful constituency will be associated with greater openness of state agencies to the public. Although not perfect, the number of organized interests in each state per policy area can serve as a good

proxy for their ability to mobilize and aff ect policy outcomes;16 this

has been used in prior work on organized interests (e.g., Gray and

Lowery 1996; Gray et al. 2004). Th us, constituency power is

opera-tionalized as the number of lobbyist organizations registered in each

state by industry type (Constituent Power). I include all industry

areas corresponding to the two agencies of interest in the study.17

Th e amount of resources at an agency’s disposal is another factor

believed to aff ect public managers’ decisions on the extent of public involvement. Seeking citizen input when making administrative decisions is desired in democratic societies, yet it is also costly. Prior

research (Wang 2001) points to the need for suffi cient funding to

ensure personnel and infrastructure needs associated with

participa-tion. Th erefore, I expect that agencies with more resources will tend

to invite greater participation than agencies with scarce resources.

Th e share of an agency’s budget from the total state budget is used

as an indicator of the relative resources that an agency has at its

of the variables indicates that the type of agency autonomy under consideration is important.

Th e coeffi cients of the control variables are mostly intuitive. Th e

coeffi cient on ConstituentPower is positive and signifi cant. One role

attributed to lobbyists is to channel information to policy makers, so more lobbyists groups are associated with higher public input in the budgeting process. In other words, agencies with powerful constituencies are systematically more likely to invite greater public participation than those with less powerful constituencies, measured as the number of lobbyist organizations registered in each state by industry type.

Somewhat surprisingly, the coeffi cients of the agency’s

resourceful-ness (Budget) and its staff (Employees) are not signifi cant. Finally,

political culture is an important determinant of the agencies’

deci-sion to “listen” to the general public. Th e positive and statistically

signifi cant coeffi cient of Moralistic Culture suggests that agencies

in states with moralistic political culture are more likely to foster participation than agencies operating in traditionalistic political

environment. Th e results confi rm by and

large the expectations regarding the low level of participation utilized by agencies in states with individualistic political culture. Despite the small number of observations, the explanatory power of the models is reason-able, from .10 to .17.

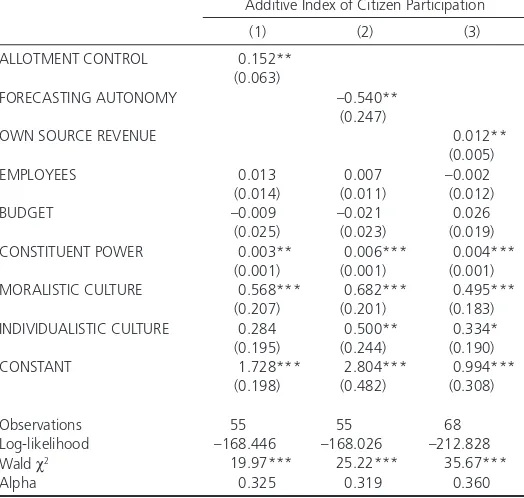

Table 4 examines the hypothesis using the additive index as a measure of public par-ticipation; because of the nature of this vari-able, the estimation technique is a negative

binomial model. Th e results confi rm the

models employ robust standard errors that allow for the

observa-tions to be clustered within each state.18

Findings and Discussion

Th e results from the models are reported in tables 3 and 4. Diff erent

operationalizations of the autonomy variable yield diff erent outcomes.

Note from column 1 that the coeffi cient of Allotment Control is

posi-tive and statistically signifi cant. Th is suggests that agencies with more

autonomy (measured as the power to allot funds) are more likely to

seek comment from the broad public. Th e weighted index is almost

25 points higher for agencies with primary responsibility for the allotment of agency funds (value of +2) than for agencies in which

the executive budget offi ce controls allotments (value of –2). By

con-trast, the coeffi cient of Forecasting Autonomy in column 2 of table 3

is negative and marginally signifi cant at the 10 percent level. Th ough

counterintuitive at fi rst, this result is consistent with the idea that the forecasting activity requires specialized knowledge and expertise

to be conducted properly. Th us, agency independence in developing

spending forecasts is not associated with a need for greater public

input. Finally, column 3 of table 3 uses Own

Source Revenue as the main variable of interest. Th e point estimate of the coeffi cient of this

variable is positive and signifi cant. Th erefore,

agencies with higher percentage of own revenues, rather than federal funds, are more likely to involve the general public. Overall, we could infer from this analysis that agencies with more control over their allotment process and agencies that manage to generate more funds on their own are more likely to consider public insights, while the opposite holds true

for forecasting control. Th e diff erential eff ect

Table 3 Ordinary Least Squares Coeffi cients for Weighted Citizen Participation Weighted Index of Citizen Participation

(1) (2) (3) CONSTITUENT POWER 0.114** 0.227*** 0.161***

(0.049) (0.036) (0.048) MORALISTIC CULTURE 25.183*** 27.875*** 20.756***

(7.842) (7.627) (7.562) INDIVIDUALISTIC CULTURE 10.560 15.199* 13.592*

(7.029) (8.941) (7.728) CONSTANT 27.005*** 80.043*** –3.705

(5.444) (26.426) (12.507)

Observations 55 55 68

F-test 6.14*** 7.41*** 7.65***

Adjusted R2 0.131 0.167 0.100

Note: Models provide coeffi cients from ordinary least squares regression estima-tion; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses.

*p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Table 4 Negative Binomial Coeffi cients for Additive Citizen Participation Additive Index of Citizen Participation

(1) (2) (3) CONSTITUENT POWER 0.003** 0.006*** 0.004***

(0.001) (0.001) (0.001) MORALISTIC CULTURE 0.568*** 0.682*** 0.495***

(0.207) (0.201) (0.183) INDIVIDUALISTIC CULTURE 0.284 0.500** 0.334*

(0.195) (0.244) (0.190)

Note: Models provide coeffi cients from negative binomial regression estimation; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses.

*p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Overall, we could infer from

this analysis that agencies with

more control over their

allot-ment process and agencies that

manage to generate more funds

on their own are more likely to

consider public insights, while

the opposite holds true for

time-consuming tasks such as public participation. Yet administra-tors face strong incentives to pursue more inclusive approaches, even

at the expense of effi ciency. Being an unelected branch, bureaucrats

are often blamed for being unresponsive to the public interest. Th us,

the inclusion of the public can potentially increase the legitimacy of agency decisions and ensure the support of critical stakeholders.

Th e evidence presented here suggests that considerations of

demo-cratic legitimacy play a considerable role in public managers’ deci-sion making: agencies with greater autonomy (measured in terms of allotment control and own-source revenues) are more likely to seek public input to inform their budget decisions.

Th is means that when given greater

budget-ary discretion, managers would rather reach out to an agency’s constituency than rely only on administrative expertise. More autonomy comes with greater responsibility on the part of public agencies, and their managers are willing to go the extra mile to ensure that

they have the support of the public. Th is is

not the case, however, if budgetary autonomy is operationalized in terms of forecasting. Conducting forecasting analyses requires technical expertise and preparation to be tackled properly. In fact, administrators are less likely to seek public input if they enjoy greater independence from politics in estimating their future spending. Hence, agency autonomy can foster public participation, but only if agencies are delegated greater autonomy to decide on the allotment of the appropriated agency funds and if

they generate more funds on their own. Th ese fi ndings are

consist-ent with previous work by Th omas (1990, 1993, 1995), who argues

that the appropriateness of public participation in administration diff ers depending on the need for quality and acceptability of agen-cy’s decisions. Decisions on how taxpayers’ money should be spent require a high degree of public acceptance. In contrast, developing spending forecasts necessitates a higher degree of quality, and thus public involvement is less appropriate.

Th e results of this study have important implications for the design

of state budget processes and the desirability of having more

auton-omous agencies. Th e fi nding that more autonomous agencies are

generally more likely to seek public input in their budget processes means that state legislatures and governors should not be fearful that granting autonomy to agencies will make them run amok or lead to less participation and buy-in from the public. Just the opposite, hav-ing greater budget autonomy comes with more responsibilities for public managers and greater willingness to stay in tune with public preferences.

Future research should extend the investigation to other policy areas and check whether the inferences registered here for trans-portation and environmental protection departments hold in other policy contexts. Both types of agencies included in this analysis need to comply with federal requirements for public participation set by legislative acts such as ISTEA and NEPA. Admittedly, there are legal requirements for public inclusion in many policy areas, but they can be met in a meaningful way or just as a formality. In this sense, future research should devote more attention to better insights from table 3. As evidenced by the positive and statistically

signifi cant coeffi cient of Allotment Control in column 1, public

participation in the budget process increases with the agency’s autonomy, operationalized by the amount of appropriation that may be expended or encumbered during a given period. By contrast, column 2 of table 4 suggests that agencies with more autonomy in their forecasting activities are less likely to seek input from the

pub-lic. Th e coeffi cient of Forecasting Autonomy is negative and signifi

-cant at the 5 percent level. Th ese insights derived from the earlier set

of models are also confi rmed when I use Own

Source Revenue as a measure of agency’s

auton-omy. Th e coeffi cient of the variable remains

positive and signifi cant as shown in column 3 of the table. Furthermore, the eff ects of the control variables observed with the weighted index remain qualitatively unchanged.

I also estimate a number of additional models

to rule out other plausible explanations.19

First, I examine whether the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches in the budget process aff ects the relationship of interest here. NASBO provides yearly data on gubernatorial budget authority, including the governor’s veto power, yet none of the

indicators associated with a strong executive achieves signifi cance in the models. Second, one could argue that budgetary autonomy and public participation are consequences of a managerial reform that grants agencies more responsibilities to meet citizens’ need (such need is better identifi ed through engaging the public directly). A study by Lu, Willoughby, and Arnett (2011) reports data on the comprehensiveness of budgeting for performance reforms and ranks the states in terms of the relative strength of their reform eff orts.

Th e results from the additional models fail to register any signifi cant

eff ect of the reforms on the relationships of interest here. Th ird,

because some states place greater emphasis on participation at the local level, I run an additional model to check for this eff ect. Berner and Smith (2004) provide data on state requirements for

participa-tion at the county and city levels. Th e estimations show that citizen

participation requirements at the local level do not signifi cantly aff ect the amount of participation invited at state agencies. Fourth, I

test the robustness of the results against population size. Th e variable

is only marginally signifi cant and does not impact the major eff ects registered under the original models. Finally, I employ a set of alternative variables to model the eff ect of political environment in states, including a nominate measure of government ideology (Berry et al. 2010), as well as measures such as divided government and two-party vote shares (Council of State Governments 2005). None of those new variables signifi cantly improves the models’ goodness of fi t or changes the inferences drawn under the original models.

Conclusion

Agencies with greater autonomy in their budget processes face confl icting incentives. On the one hand, independence from the executive allows agency management to deploy a strictly

techno-cratic and effi cient mode of operation that relies on the agency’s

expertise and experience. Given the long-standing reliance of public administration on the values of bureaucratic ethos, it seems plausi-ble that agencies would invoke instrumental rationality and ignore

Th

e evidence presented here

suggests that considerations

of democratic legitimacy play

a considerable role in public

managers’ decision making:

agencies with greater autonomy

(measured in terms of

allot-ment control and own-source

revenues) are more likely to seek

11. I initially considered one more operationalization of budget autonomy based on agency authority to develop multiyear programs. Yet this measure has been dropped from the analysis because of the lack of variation within it.

12. It should be noted that in times of unanticipated revenue shortfalls, it is not unusual for the executive to reduce allotments across the board to all state agen-cies. Th e executive may also reduce allotments for a specifi c agency for a variety of reasons, for example, if the agency is overspending and the executive wants to reduce its autonomy.

13. I recognize that there might be important distinctions in the types of own-source revenue; for example, agencies that utilize large amounts of general state income/ sales tax might be less autonomous than those with dedicated revenue sources. 14. Values for 2004 are used for all variables in the models (where missing, values for

2005 are used).

15. Th e amount and types of intra-agency transfers could be another useful proxy of autonomy. Th e selection and composition of the organizational leaders can also be indicative of the level of organizational discretion.

16. Admittedly, measuring the number of lobbying organizations captures only part of power, as we are not able to gauge the intensity of their lobbying eff orts. 17. Th e fi gures are taken from http://www.lobbyists.info/.

18. To check for possible multicollinearity in the models, I examine the variance infl ation factor (VIF) statistics and the condition number of the matrix of independent variables (Greene 2002). As a rule of thumb, VIF values exceeding 5 and condition numbers exceeding 20 could be a source of concern. It is reas-suring that no variable exhibits VIF greater than 2, and the condition numbers, based on the set of our three main models, are far below the threshold. Th us, even if multicollinearity might be present in the data, it should not substantially aff ect the inferences drawn from the models.

19. Th e results of the robustness tests are available from the author upon request.

References

Abney, Glenn, and Th omas P. Lauth. 1985. Th e Line-Item Veto in the States: An Instrument for Fiscal Restraint or an Instrument for Partisanship? Public Administration Review 45(3): 372–77.

Anderson, Stephen H., and Natalia V. Smirnova. 2006. A Study of Executive Budget-Balancing Decisions. American Review of Public Administration 36(3): 323–36.

Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35(4): 216–24.

Baiocchi, Gianpaolo. 2003. Emergent Public Spheres: Talking Politics in Participatory Governance. American Sociological Review 68(1): 52–74.

Berman, Evan M. 1997. Dealing with Cynical Citizens. Public Administration Review

57(2): 105–12.

Berner, Maureen, and Sonya Smith. 2004. Th e State of the States: A Review of State Requirements for Citizen Participation in the Local Government Budget Process.

State and Local Government Review 36(2): 140–50.

Berry, William D., Richard C. Fording, Evan J. Ringquist, Russell L. Hanson, and Carl Klarner. 2010. Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States: A Re-Appraisal. State Politics and Policy Quarterly 10(2): 117–35.

Carpenter, Daniel. 2001. Th e Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy: Reputations, Networks, and Policy Innovation in Executive Agencies, 1862–1928. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Clynch, Edward J., and Th omas P. Lauth. 2006. Budgeting in the States: Institutions, Processes, and Policies. In Budgeting in the States: Institutions, Processes, and Politics, edited by Edward J. Clynch and Th omas P. Lauth, 1–8. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Council of State Governments. 2005. Th e Book of the States. http://

knowledgecenter.csg.org/kc/category/content-type/content-type/book-states/ bos-2005 [accessed December 10, 2013].

understanding the motivation of public managers to seek greater public input in situations in which competing incentives are likely to be at play. Because the decisions about the forms and extent of public participation reside solely with the administrators, it is of crucial importance to examine under what conditions they would opt for meaningful participation. Are these decisions aff ected by the values held by individual administrators? Or are they infl uenced by the values shared within their respective agencies? In a sense, both quantitative and qualitative studies are needed to prove the generalizability of these fi ndings and to better understand the causal explanations behind statistical associations.

Notes

1. Both agencies are freestanding in their operations (rather than being part of an umbrella agency); they are among the main departments of state government and are present in each state.

2. In some states, agencies can directly submit their requests to the legislature with-out an initial review and approval from the executive budget offi ce. However, that is not the usual practice.

3. Th e name of the agency varies from state to state. Besides Environmental Protection Agency (California, Illinois, Ohio) and Department of

Environmental Protection (Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania), it is also called Department of Environmental Quality (Arizona, Idaho, Michigan, Oregon), Department of Environmental Management (Alabama, Indiana), and Department of Environmental Conservation (New York, Alaska).

4. Th e Government Performance Project (GPP) is a periodic survey conducted on state government management practices in the areas of human resources, budget-ing and fi nancial management, infrastructure, and information. Sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts and its Center on the States, the project involves both aca-demic and journalist partners for the collection, analysis, and reporting of data. A complete accounting of this research methodology, survey development, responses, and analyses of the GPP survey is available at http://www.pewcenteronthestates. org/gpp. Th is article was developed using data from a number of sources, including data generated by the GPP. Th e views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the GPP or the Pew Charitable Trusts. 5. Th e GPP data on state governments’ management and performance have been

used to answer various research questions (e.g., Krueger and Walker 2010; Rubin and Willoughby 2009; Selden and Wooters 2011).

6. It should be acknowledged that the data used in the study were collected prior to the Great Recession and thus might not completely refl ect all current patterns. 7. Th e particular question reads, “We are interested in any strategies that your

agency has used to generate input from citizens concerning budget priorities, development and/or assessment. Specifi cally, if your agency has engaged in any of the strategies below to gain citizen input, indicate if the strategy has been use-ful in terms of the outcomes listed (Check all that apply for each strategy).” 8. Th e survey asks about the strategies used by agencies to engage the public and

their relative usefulness at the diff erent stages of the budget process, but not about actual engagement level.

9. Th e particular survey question reads, “Th e next few questions ask about agency budget management and responsibilities. In this question, using the scale below, please indicate the degree of responsibility of your agency and the state’s execu-tive budget offi ce concerning the following activities.”