the two groups as noted above for the whole series. A difference in exclusion criteria would

potentially

have had aprofound

effect on the relative remission rates of the twogroups.

DISCUSSION

We believe this

patient

series to berepresentative

of the full clinical spectrumof AML,

and have shown that if allpatients

are taken into account, the clinical course may be lesssuccessful than

previously

thought. 2-4

A

large

number ofpatients

(43/272)

were notgiven

chemotherapy.

In most cases, this was because theattending

physician

judged

thepatient

to beunlikely

to withstandchemotherapy.

Thesepatients

are never included intreatment series and yet a discussion of treatment results and

prognosis

with newpatients

should include this information.31

patients

were started onchemotherapy

but did notcomplete

asingle

course of treatment,usually

because of infectiouscomplications leading

toearly

death. Treatment series will often exclude suchpatients

as"inevaluable",

butthey

are betterregarded

as treatment failures.Many

treatment series report an averagepatient

age of 45 to50

years,’ 2-14

whereas the mean age of all AMLpatients

and the mean age in ourseries,

is60.15

Protocols may excludepatients

over50, 60,

or 70years,12,16,17

or thesepatients

maynot be referred to treatment centres. Patients with

preceding

myelodysplastic

syndromes,

andpatients

in whom AMLdevelops secondary

tocytotoxic chemotherapy

have been shown torespond

poorly

tochemotherapy

forleukaemia.6

Patients with poor

prognostic

variables have beensegregated

in separateseries.7,8,18

It islikely,

therefore,

that thesepatients’

are alsogenerally

excluded from recentchemotherapy

series. If we excludepatients

aged

70 and over,patients

withpreceding myelodysplastic syndromes,

andpatients

withprevious chemotherapy, analysis

shows ahigh

complete

remission rate(85-307o)

asreported

in otherseries.2-4

Reports

of recentimprovements

inchemotherapy

for AML may reflect inadvertent exclusions and refinements inleukaemia classification rather than true

improvement

intreatment

results.190ur

new treatmentregimen

led to animprovement

incomplete

remission rate but nosignificant

difference in overall mediansurvival,

when allpatients

are taken into account. Ifonly

the second series weresubject

tothe exclusions we have

discussed,

the apparentimprovement

could have been considerable. The remission rate for allpatients

in the first series(35%) might

then becompared

with the remission rate forpatients

with various exclusions in the second series(60 - 90%).

Results of treatment trials in AML that show an overall

improvement

in results should include ananalysis

ofpatients

who are untreated orpartially

treated,

and theproportion

ofpatients

with adverseprognostic

indicators.This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of Canada and Grant CA31761-04A2 from the National Cancer Institute, USA, and the William J. Matheson Foundation.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Michael A. Baker, Oncology

Clinic, Toronto General Hospital, 657 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7, Canada.

REFERENCES

1. Bloomfield CD. Treatment of adult acute nonlymphocytic leukemia-1980 Ann Int Med 1980; 93: 133-34.

consolidation therapy in adult acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1984, 63: 843-47.

6. Estey EH, Keating MJ, McCredie KB, Bodey GP, Freireich EJ. Causes of initial

remission induction failure in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 1982; 60: 309

7. Preisler HD, Early AP, Raza A, et al. Therapy of secondary acute nonlymphocytic

leukemia with cytarabine. N Engl J Med 1983; 308: 21.

8. Capizzi RL, Poole M, Cooper MR, et al. Treatment of poor risk acute leukemia with

sequential high dose ARA-C and asparaginase. Blood 1984; 63: 694-700. 9. Harousseau JL, Castaigne S, Milpied N, Marty M, Degos L Treatment of acute

non-lymphoblastic leukaemia in elderly patients. Lancet 1984; ii: 288

10. Yates J, Wallace J, Ellison RR, Holland JF Cytosine arabinoside (NSC-63878) and daunorubicin (NSC-83142) therapy in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Chem Rep 1973; 57: 485-88.

11. Baker MA, Taub RN, Carter WH, and the Toronto Leukemia Study Group Immunotherapy for remission maintenance in acute myeloblastic leukemia Cancer Immunol Immunother 1982; 13: 85-88

12. Sauter C, Fopp M, Imbach P, et al Acute myelogenous leukaemia: maintenance

chemotherapy after early consolidation treatment does not prolong survival Lancet

1984; i: 379-82.

13. Buchner T, Urbanitz D, Fischer J, et al. Long-term remission in acute myelogenous

leukaemia Lancet 1984; i: 571.

14. Champlin R, Gale RP, Elashoff R, et al. Prolonged survival in acute myelogenous

leukaemia without maintenance chemotherapy. Lancet 1984, i: 894-96 15 Wintrobe MM, Lee GR, Boggs DR, et al, eds. Classification, pathogenesis and etiology

of neoplastic disease of the hematopoietic system. In Clinical hematology

Philadelphia Lea and Febiger, 1981: 1455-58.

16. Weinstein HJ, Mayer RJ, Rosenthal DS, Camitta BM, Coral FS, Nathan DG, Frei E Treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia in children and adults N Engl J Med

1980, 303: 473-78.

17. Cassileth PA, Begg CB, Bennett JM, et al A randomized study of the efficacy of

consolidation therapy in adult acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1984; 63:

843-47.

18. Keating MJ, McCredie KB, Benjamin RS, et al. Treatment of patients over 50 years of

age with acute myelogenous leukemia with a combination of rubidazone and cytosine arabinoside, vincristine and prednisone (ROAP) Blood 1981, 58: 584

19. Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in

cancer. N Engl J Med 1985; 312: 1604-08

20 The Toronto Leukemia Study Group. Survival in acute myeloblastic leukemia is not

prolonged by remission maintenance or early reinduction chemotherapy Blood

1985; 66 (suppl): 210a.

Trial

Design

IS A CONTROLLED TRIAL OF LONG-TERM

ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS IN PATIENTS WITH

STROKE AND NON-RHEUMATIC ATRIAL

Walton

Hospital,

Liverpool;Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford;

and Northern GeneralHospital,

Sheffield

Summary

A controlled randomised triallarge

enough

to assess the value of

anticoagulating

strokepatients

in atrial fibrillation would be difficult to conduct inthe UK and the results would be

applicable

toonly

a smallproportion

of strokepatients.

It would be more worthwhile toorganise

a trial that also assessed the value of other treatments that aresimpler

andapplicable

to all strokepatients.

A trialthat assessed the value of

aspirin

and beta-blockersagainst

control in all strokepatients

would not cost much more thanone restricted to

comparing

anticoagulants against

control inpatients

with stroke and atrial fibrillation but wouldprovide

information of more relevance to the managementof patients

with stroke in the UK.

INTRODUCTION

MANY stroke

patients

in atrial fibrillation(AF)

aregiven

TABLE I-POSSIBLE RANDOMISED TRIAL DESIGN TO INCLUDE ALL

STROKE PATIENTS (AF AND SINUS RHYTHM)

BB=betablocker. AC= oral anticoagulant.

To assess various anti-haemostatic therapies: X versus Y versus Z. To assess beta-blockade: 1 versus 2.

anticoagulant

versus controlought

to be conducted.However,

there are reasonswhy

a very different trialmight

bebetter. The alternative trial would include not

just

those in AF but all strokepatients;

it would be acomparison

ofanticoagulants

versus control versusaspirin;

andfinally

half of each of the three groups would begiven beta-blockers,

todiscover whether these agents were of any additional value

(table I).

Thedesign

of this trial was based on thefollowing

general

considerations;

that the type and number of strokepatients

in AFlikely

to enter the first type ofstudy

may belimited;

that the outcome forpatients

with AF is not much different from that for those in sinusrhythm

and that moststroke

patients

die not of stroke but of heartdisease,

sotreatments that

might

reduce heart disease need to bestudied;

thatanticoagulants

may reduce the incidence of heart disease and occlusive stroke but increase the incidence ofhaemorrhagic

stroke;

thataspirin

and beta-blockers may be as effective asanticoagulants

but are easier togive

and lesstoxic;

and

finally

that there are many more strokepatients

in sinusrhythm

than inAF,

which makes the former much easier tostudy

and of much greaterpublic

healthimportance.

We concludeby asking

whether asimpler

trial(paradoxically,

without the twoanticoagulant subgroups) might

be evenbetter in a country, such as Great

Britain,

where computertomography (CT)

is often notreadily

available for the detectionof haemorrhagic

stroke(in

whichanticoagulants

are

contraindicated).

The evidence reviewed derives from manysources,

including

the OxfordshireCommunity

StrokeProject

(OCSP),’

in which 512 consecutive cases of first-ever stroke wereinvestigated .

WHAT IS A TYPICAL STROKE PATIENT IN AF LIKE?

The sort of stroke

patient

in whom thequestion

ofanticoagulation typically

arisesmight

be anelderly

womanwith a mild

right hemiparesis,

hypertension,

a left carotidbruit,

and atrial fibrillation but no evidence of rheumaticvalvular disease. The decision to

anticoagulate

shouldideally

be based on: whether the stroke was due to cerebral infarction orprimary

intracerebralhaemorrhage (this

requires

a CT scan of thebrain);

if the stroke was due to infarction whether it was a result ofhypertensive

small vessel disease within thebrain,

embolism from an atheromatousplaque

in the internal carotid artery, or embolism from thefibrillating

leftatrium;

and whether it is wise to

subject

anelderly hypertensive

patient

to the risks and inconvenience ofanticoagulation.

WHAT IS THE EFFECT OF AF ON RISK OF DEATH AND RECURRENT STROKE IN STROKE PATIENTS?

Although

AF not associated with rheumatic heart disease(NRAF)

may increase the risk of death in the first 30days

after astroke,

it has a less marked effect onmortality

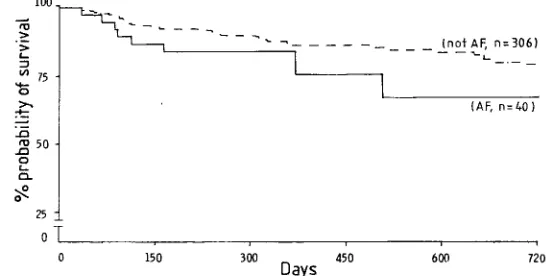

Fig 1-Probability of survival (Kaplan-Meier survival curve) among 346 patients who survived at least 30 days after a first cerebral

infarction.

Data from the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project.

TABLE II-RISK OF DEATH OR RECURRENT STROKE IN PATIENTS WITH STROKE AND ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

RHD = cases ofAF associated with RHD; NRHD = cases ofAF not associated with RHD; NK = not known.

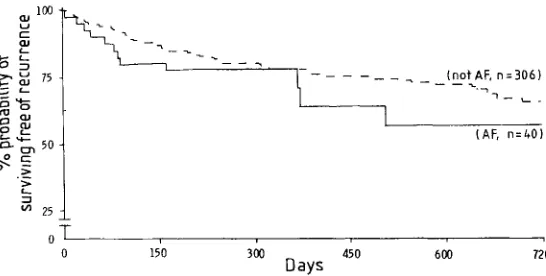

Fig 2-Probability of remaining free of recurrent stroke among 346

patients who survived at least 30 days after a first cerebral

infarction.

Data from the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project.

thereafter.

However,

it is the30-day

survivors who would bemost

likely

to be entered into along-term

trial ofanticoagulants (table

II andfig 1).

In thelong

term NRAFseems to have little effect on the risk of recurrent stroke

(table

II andfig

2).

Thepossibility

thatpatients

with stroke and NRAF may be at greater risk ofearly

recurrence(within

the firstmonth)

thanpatients

in sinusrhythm3-’

has not beenconfirmed;6,7

the OCSP data so far show that the 6 recurrentstrokes in OCSP

patients

with AF have all occurred more than 1 month after the first stroke.WHAT IS THE EFFECT OF RHEUMATIC HEART DISEASE

(RHD)

ON RISK OF RECURRENT STROKE?In AF

patients

who have not had astroke,

the presence of RHD increases the relative risk of first-ever strokeapproximately

threefold,

from 5 - 6 to17. 6.8 However,

thereare no reliable data on how much RHD influences the

frequency

of recurrent stroke inpatients

withAF,

though

therisk is often assumed to be much

higher

with than without RHD. In the OCSPonly

5/68(7%)

of the cases of first-everstroke in AF had RHD.

Therefore,

even if it wereaccepted

that those with RHD should beanticoagulated,

the treatmentpolicy

for stroke and AF in the 90% or so without RHDmight

still be open to debate(but

this dilemma may not arise in theparts of world where the

prevalence

of RHD ishigh).

WHAT IS THE EFFECT OF ANTICOAGULANTS ON RISK OF RECURRENT STROKE?

The

only

randomised controlled trial ofanticoagulants

inpatients

with stroke attributed to embolism from the heartwas small

(28

patients)

and did not state the criteria fordiagnosis

of embolicstroke,

the number ofpatients

withAF,

or the number with

RHD.9

There have been extensive reviews of non-randomised studies ofanticoagulants

inpatients

with stroke that waspresumed

to be due to embolism from theheart,5,10-12

and some of the reviews have come outvery

strongly

in favour of the use ofanticoagulants. But,

non-randomised studies do not in

general

yield

reliable data and when historical controls have beenused,

claims such as "...in studies of

anticoagulation

... inpatients

with cerebralembolism ... there has been a 65 to 90% reduction in the number

ofembolic accidents"’2

should beinterpreted

withcaution. In

addition,

many of the studies were done before CTscanning

was available and most included ahigh

proportion

of cases withRHD,

so their relevance to thetreatment of strokes in the UK in the 1980s, when RHD is

relatively

uncommon, is debatable.A

rough

idea of thelikely

reduction in risk of stroke thatanticoagulation might

confer onelderly people

may beobtained from a

study

of the use ofanticoagulants

aftermyocardial

infarction inpatients aged

over60.’

Thisstudy

waslarge

and randomised andattempted

to determineby

CT scan and/or necropsy whether strokes that did occurwere ischaemic or

haemorrhagic.

There were 4 cases ofCT-proved

cerebral infarction among the 493patients

allocatedplacebo

andonly

1 among the 493 allocatedanticoagulants (a

risk reductionof 70%).

However,

there were 7 cases(6

fatal)

of definite intracranial

haemorrhage (ICH)

in the treated group andonly

1 in the control group.Thus,

if cases ofdefinite cerebral infarction and definite ICH were

counted,

anticoagulants

caused a 60% net increase in the risk of stroke. The numbers of cases were very small and the confidenceintervals

wide,

so no firm conclusions can be drawn.Nevertheless,

thefindings

show theimportance

ofbalancing

any reduction in the risk of cerebral infarction

against

anyincreased risk of ICH in studies of stroke

prevention.

WHAT IS THE EFFECT OF ANTICOAGULANTS ON RISK OF INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGE?

Despite

thehigh

relative risk of ICH inanticoagulated.

patients,

the absolute number ofpatients

with ICH is still small.Unfortunately,

ICH may nevertheless be thecommonest fatal

complication

ofanticoagulant

therapy. IS

However,

itsfrequency

inpatients

with well-controlledprothrombin

times is still not known.Widespread,

inadequately

controlled use ofanticoagulants

in the 1960s may well have caused anappreciable

increase in thefrequency

of ICH inRochester,

Minnesota.16

InLeiden,17

where

anticoagulant

therapy

is centralised and veryclosely

supervised, anticoagulants

increased the risk of ICH ten-foldin

people

over 50. A similar increase in risk occurred inover-60s

given

oralanticoagulants

aftermyocardial

infarction.14

The risks of ICH in

patients

who havealready

had a strokeare rather different. For stroke due to

ICH,

anticoagulants

areobviously strongly

contraindicated,

soearly

CTscanning

torule out ICH before

starting

anticoagulant

treatment for anytype of stroke is

mandatory. 18-20

However,

a cerebral infarction may be followedby

spontaneoushaemorrhage

intothe infarcted area, and

anticoagulants

may exacerbate thistendency

(even

ifprothrombin

activity

remains within anacceptable

therapeutic

range). 111,11,21-2’

The risk of a"pale"

cerebral infarct

becoming

a"haemorrhagic"

infarct ishighest

in

patients

withlarge

infarcts orhypertension

and,

notsurprisingly,

inpatients given

excessive doses ofanticoagulants. 21-21

The difficulties ofcontrolling

anticoagulant

therapy

in strokepatients

with AF arecompounded by

the age of most of thepatients.

In the OCSP57/68

(84%)

of thepatients

with first strokes in AF wereaged

70 or over and 24/68

(35%)

wereaged

80 or over.Although

age did not affect the relative risk of ICH due to

anticoagulants

in the Leidenstudy,l

the absolute risk mayrise very

steeply

withage.15,26-28

Moreover,

supervision

ofanticoagulants

inelderly

patients

may be difficult:they

maybe on several other

drugs,

so that interactions may occur,drug compliance

may be poor(especially

after astroke);

andthey

may havedifficulty

inattending

ananticoagulant

clinic.Hypertension,

whichgreatly

increased the risk of ICH forpatients

with stroke andAF;

forexample,

54% of the OCSP series weredefinitely hypertensive (at

least two bloodpressures greater than 160/90 mm

Hg

recorded before thestroke),

and inKelley’s

study29

78% ofpatients

with stroke and AF werealready

onantihypertensive

drugs

at the time ofadmission.

IS A RANDOMISED CONTROLLED TRIAL NEEDED?

As discussed

above,

after oralanticoagulation

the netreduction in risk of recurrent

stroke-and,

moreimportantly,

ofdisabling

and/or fatal stroke-could be modest inpatients

with NRAF. The risk of ICH may beparticularly

high

sincemany such

patients

areelderly

and/orhypertensive.

Arandomised trial is therefore necessary to assess the balance of risks and benefits

of anticoagulant

treatment inpatients

with stroke and non-RHD AF.7,3O A similarstudy might

also beappropriate

for the smallminority

offibrillating

strokepatients

who do haveRHD, though

few clinicians would consider such a trial ethical.WHAT PROPORTION OF STROKE PATIENTS ARE SUITABLE FOR ANTICOAGULATION?

The OCSP data

(fig 3)

suggest thatonly

13/68(19%)

casesof first stroke with AF were suitable for

anticoagulant

Fig 3-Number of first strokes in AF suitable for anticoagulant therapy in the OCSP.

*Includes five cases ofAF associated with RHD.

tNo CT scan or necropsy performed.

$Some patients had more than one contraindication. Hypetension=two _ BP>160/90 mm Hg recorded before stroke.

§Severe stroke=hemiplegia, aphasia, and/or coma, survived >72 h; very disabled before stroke=needs assistance to walk and to attend to own body and/or bedbound.

TABLE

III-LIKELY

NUMBER OF PATIENTS WITH CT-PROVEN ISCHAEMIC STROKE AND NON-RHEUMATIC ATRIAL FIBRILLATIONAVAILABLE FOR CLINICAL TRIAL OF ANTICOAGULANTS Number available in England and Wales

First strokes in England and Wales each year* =96 000

ofwhoml3-3%inAF =12770

of whom 16-2% have non-RHD AF and "suitable for

anticoagulant therapy" = 2100

of whom 50% might enter a trialt = 1050

Number avazlable zn average datrict general hospital

(servmg about 250 OOO/yr)

Number of strokes per year =500

of whom 50% admitted to hospital =250

of whom 13.3% m AF = 33

of whom 16-2% have non-RHD AF and "suitable for

anticoagulant therapy" = 5

of whom 50% might enter a trial = 3

*From OCSP.1

t Previous multicentre trials suggest that about 50% of the patients eligible to enter the trial are not entered for a variety of reasons (patient refusal, follow-up

likely to be difficult, &c.).

therapy,

aproportion

similar to thatreported

fromScandinavia:31 however,

2 of these cases had RHD(and

1 of these wasalready

onanticoagulants).

Thusonly

11/512(2%,

95% confidence limits 0 - 8-3’

2%)

of all first strokes wouldhave been

eligible

for a trialof anticoagulation

in NRAF andstroke. Such a

study

would not be of direct relevance to 98%of strokes.

Nonetheless,

2% of all first strokes isequivalent

toabout 2000 cases in

England

and Wales a year. Inpractice,

only

a smallproportion

of thesemight

enter a randomisedtrial

(table III).

Would a trial infibrillating

strokepatients

thusbe feasible?

WHAT SIZE OF SAMPLE IS REQUIRED FOR A TRIAL OF ANTICOAGULANTS IN STROKE WITH NRAF?

If anticoagulants

can reduce thefrequency

of stroke and/or deathby

about30%,

then about1500

patients

would have tobe randomised and followed up for a few years if there is to be

a reasonable chance

(90%)

ofgetting

aconventionally

significant

result(p<O’ 05).32

It wouldprobably

bepracticable

to enteronly

inpatients,

and ourexperience

(table

III)

suggests that ahospital might

be able to enteronly

about 2 or 3patients

peryear,

so well over 100hospitals might

berequired.

Furthermore,

since allpatients

wouldrequire

a CT scan before randomisation to excludeICH,

only

the limitednumber of

hospitals

in the UK withrapid

access to a CT scanner couldparticipate,

so it wouldprobably

beimpossible

to recruit the numbers that

might

be needed for anadequate

study.

However,

if the true risk reduction is much better thanone-third,

then much smaller numbers ofpatients

wouldsuffice;

conversely

if attention was restricted to fatal ordisabling

strokes,

farlarger

numbersmight

berequired.

IS A TRIAL OF ANTICOAGULANTS IN NRAF WORTHWHILE?

A trial that had to recruit

subjects

from many centres would be difficult toorganise,

would beexpensive,

and wouldrequire

considerable effort to ensure strict adherence to theprotocol (especially

with respect toprothrombin

measure-ment for control oftherapy).

Furthermore,

if the resultswould be

applicable

toonly

about 2% of all firststrokes,

froma

public

healthviewpoint

at least, the value of a trial ofanticoagulants

restricted to strokepatients

with NRAF seemsless worthwhile than at first.

SHOULD THE TRIAL INCLUDE ALL PATIENTS WITH ISCHAEMIC STROKE?

Since the

long-term

outcome after ischaemic stroke seems to be similar whetherpatients

are in AF or sinusrhythm

(table

II)

and since the valueof anticoagulants

in either type ofpatient

has not beenreliably

established,33

there could be a case fortesting

anticoagulants

in allpatients

with ischaemic stroke.However,

we think that most clinicians would nothave as much enthusiasm for such a trial. Indeed many

might

be disturbed at the prospect, if the trial were to be

positive,

of thousandsof elderly

strokepatients being

given long-term

anticoagulants.

Furthermore,

the number of CT scans thatwould have to be done may be an

impossible

burden forBritain’s

already

stretched CTscanning

facilities.’9

ARE THERE OTHER TREATMENTS THAT ARE SIMPLER, MORE WIDELY APPLICABLE, AND LIKELY TO CONFER USEFUL

BENEFIT?

Death after transient ischaemic attack

(TIA)

and stroke ismore often due to ischaemic heart disease than to recurrent

stroke.34-36

Aspirin,

takendaily

for months or years aftermyocardial

infarction,

reduces the risk of deathby

about 15% and of furthermyocardial

infarctionby

about25%.

Beta-blockers reduce themortality

aftermyocardial

infarctionby

about25%.38

Furthermore,

there is somesuggestion

thataspirin given

after TIA and mild ischaemic stroke reduces the risk ofsubsequent

death and recurrentstroke;39

this effect isbeing

assessedby

the UK TIAaspirin

study

andby

a collaborativeanalysis

ofpublished

trials.Apart

fromsimplicity

and wideapplicability

these two agents have theadvantage

that a CT scan may not be necessary before start oftreatment to exclude ICH-a

simple

clinicalscoring

systemmight

beadequate. 21

WHAT IS THE DESIGN OF THE IDEAL TRIAL?

The

simplest

trial that would answer most of theimportant

questions

(ie,

areanticoagulants

andaspirin

eacheffective,

and, if so,

which is the moreeffective?)

would be to allocate all strokepatients (AF

and sinusrhythm

subgroups

can still beanalysed separately)

randomly

to one of three treatments(placebo, aspirin,

or oralanticoagulants).

This trial wouldrequire

an 11%larger sample

than a trial ofplacebo

vsanticoagulants.

A factorialdesign

would allow beta-blockersto be tested as well without further

increasing

thesample

size(table I).

Such a trial islikely

to be no moreexpensive

in termsof money or effort than one of

anticoagulants

versusplacebo

but would

provide

more answers.CONCLUSIONS

A trial of

long-term

oralanticoagulants

inpatients

with ischaemic stroke and NRAF or in all ischaemic stroke wouldperhaps

be done moreeasily

in countries(such

as the Netherlands or theUSA)

where ahigh

proportion

of strokesare admitted to

hospitals

with CT scanners. In theUK,

it would be more worthwhile to concentrate collaborative efforts(and

limitedresources)

on the reliable assessment ofsimpler,

morewidely practicable

treatments forsecondary

strokeprevention

whichmight

beapplicable

to allpatients

with ischaemicstroke;

aspirin

and beta-blockers are two suchagents which we believe could-and should be-tested.

Data from the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project formed the basis for this paper and we would therefore like to thank all those who collaborated with

us in that study. The Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project is funded by the MRC with additional support from the Chest, Heart and Stroke Association.

Correspondence should be addressed to P. S., Department of Neurology,

Walton Hospital, Rice Lane, Liverpool L9 lAE.

REFERENCES

1 Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project Incidence of stroke in Oxfordshire: first year’s experience of a community stroke register Br Med J 1983, 287: 713-17 2 Lowe GDO, Forbes CD, Jaap AJ Relation of atrial fibrillation and high haematocrit to

mortality in acute stroke Lancet 1983, i: 784—86

3 Wolf PA, Kannel WB, McGee DL, Meeks SL, Bharucha NE, McNamara PM Duration of atrial fibrillation and imminence of stroke the Framingham study Stroke 1983, 14: 664-67

4. Easton JD, Sherman DG. Management of cerebral embolism of cardiac origin Stroke

1980, 11: 433-42

5. Sherman DG, Goldman L, Whiting RB, Jurgensen K, Kaste M, Easton JD,

Thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation Arch Neurol 1984, 41: 708-10

6. Britton M, Gustafsson C Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for stroke

Stroke 1985, 16: 182-88

7 Sage JI, Van Uitert RL Risk of recurrent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation and non-valvular heart disease Stroke 1983; 14: 537-40

8. Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas HE, Kannel WB Epidemiologic assessment of chronic

atrial fibrillation and stroke the Framingham study Neurology 1978, 28: 973-77 9. Baker RN, Broward JA, Fang HC, et al Anticoagulant therapy in cerebral infarction

Report on cooperative study Neurology 1962; 12: 823-29

10 Genton E, Barnett HJM, Fields WS, Gent M, Hoak JC. XIV Cerebral ischaemia. the role of thrombosis and antithrombotic therapy Stroke 1977, 8: 150-75

11 Yatsu F, Mohr JP Anticoagulant therapy for cardiogenic emboli to brain Neurology,

1982, 32: 274-75

12 Mohr JP, Fisher CM, Adams RD Cerebrovascular Disease. In. Isselbacher KJ, Adams RD, Braunwald E, Petersdorf RG, Wilson JD, eds. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (9th edn), New York McGraw-Hill, 1980 1932.

13 Sixty plus reinfarction study group A double-blind trial to assess long-term oral

anticoagulant therapy in elderly patients after myocardial infarction Lancet 1980, ii:

989-94.

14. Sixty plus reinfarction group. Risks of long-term oral anticoagulant therapy in elderly

patients after myocardial infarction Lancet 1982, i: 64-68

15 Silverstein A Neurological complications of anticoagulant therapy. Arch Intern Med

1979, 139: 217-20

16 Furlan AJ, Whisnant JP, Elveback LR The decreasing incidence of primary intracranial haemorrhage a population study Ann Neurol 1979; 5: 367-73 17. Wintzen AR, de Jonge H, Loeliger EA, Bots GTAM Risk of intracerebral

haemorrhage during oral anticoagulant treatment, a population study Ann Neurol

1984, 16: 553-58

18 Ruff RL, Dougherty JH Evaluation of acute cerebral ischaemia for anticoagulant therapy computed tomography or lumbar puncture. Neurology 1981; 31: 736-40 19. Sandercock PAG, Molyneux A, Warlow CP The value of CT scanning in patients with

stroke The Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project Br Med J 1985, 290: 193-97

20. Sandercock PAG, Allen CMC, Corston RN, Harrison MJG, Warlow CP Clinical diagnosis of intracranial haemorrhage using the Guy’s Hospital Diagnostic Score Br Med J 1985; 291: 1675-77

21 Shields RW, Laureno R, Lachman T, Victor M. Anticoagulant-induced haemorrhage

in acute cerebral embolism Stroke 1984, 15: 426-37

22 Drake ME, Shin C. Conversion of ischaemic to haemorrhagic infarction by

anticoagulant administration Arch Neurol 1983, 40: 44-46.

23. Lodder J, Van der Lugdt PJM Evaluation of the risk of immediate anticoagulant

treatment in patients with embolic stroke of cardiac origin Stroke 1983; 14: 42-46

24 Cerebral embolism study group Immediate anticoagulation of embolic stroke Brain

haemorrhage and management options. Stroke 1984, 15: 779-89.

25 Ramirez-Lassepas M, Quinones MR. Heparin therapy for stroke haemorrhagic

complications and risk factors for intracerebral haemorrhage. Neurology 1984; 34: 114-17

26. Roos J, Joost HE The cause of bleeding during anticoagulant treatment Acta Med

Scand 1965, 178: 129-31.

27 Heyman A, Nefzger MD, Acheson RM. Epidemiotogic study of the relationship of

anticoagulant therapy to mortality from intracranial haemorrhage Trans Am Neurol Assoc 1912, 97: 152-55

28. Loeliger EA Drugs affecting blood clotting and fibrinolysis In: Dukes MNG, ed Side effects of drugs, 9th ed. Amsterdam- Excerpta Medica, 1980; 9: 587-613 29 Kelley RE, Berger JR, Alter M, Kovacs AG Cerebral ischaemia and atrial fibrillation

a prospective study Neurology 1984, 34: 1285-91

30. Starkey IR, Warlow CP The secondary prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Neurol 1986; 43: 66-70

31. Norrving B, Nilsson B. The serious outcome in cerebral embolism of cardiac origin

J Neurol 1985, 232 (suppl) 115.

32. Taylor DW, Sackett DL, Haynes RB. Sample size for randomised trials in stroke prevention. How many patients do we need? Stroke 1984; 15: 968—71 33 Warlow CP Cerebrovascular disease Clins Haematology 1981; 10: 631-51 34. Marquardsen J The natural history of acute cerebrovascular disease: a retrospective

survey of 789 patients Copenhagen Munksgaard, 1969 147

35. Heyman A, Wilkinson WE, Hurwitz BJ, et al. Risk of ischaemic heart disease in

patients with TIA. Neurology 1984; 34: 626-30.

36. Matsumoto N, Wisnant JP, Kurland LT, Okazaki H. Natural history of stroke in

Rochester Minnesota 1955 through 1969: extension of a previous study 1945

through 1954 Stroke 1973, 4: 20-29

37. Anon (editorial) Aspirin after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1980; i: 1172-73

38 Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Betablockade during and after

myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomised trials. Progr Cardiovasc Dis

1985; 27: 335-71.

39 Canadian cooperative study group. A randomized trial of aspirin and sulphinpyrazone