Teacher education for inclusion: Can a virtual learning object help?

Cl

audia Alquati Bisol

a,*, Carla Beatris Valentini

b, Karen Cristina Rech Braun

aaDepartment of Psychology, University of Caxias do Sul, Rua Francisco Getúlio Vargas, 1130, CEP 95070-560, Caxias do Sul, Brazil bDepartment of Education, University of Caxias do Sul, Rua Francisco Getúlio Vargas, 1130, CEP 95070-560, Caxias do Sul, Brazil

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Inclusive education has occupied a central role in educational planning especially over the last two decades of the 20th century. This article presents an evaluation of the virtual learning object (LO) Incluirda digital resource designed to support learning. It was created to work as a complementary tool for teacher education that aimed at promoting reflection on inclusion and resignification of teachers' practice. We present some aspects of inclusive education in Brazil and our perspective on teacher ed-ucation for inclusion. Then we explore the learning object, the pedagogical framework that guided its conception, and the survey that we conducted designed to evaluate the object in its technical and pedagogical aspects. A total of 163 participants answered a questionnaire comprised of 20 closed questions and 3 open-ended questions. Simple descriptive statistics allowed us to determine that par-ticipants rated the object very positively. Thematic content analysis was used to organize the qualitative data of the two open-ended questions in three analytical categories. Simple quantification and description was used to analyze the third open-ended question. We concluded that the LO is a valuable complementary resource that contributes to teacher education for inclusion.

©2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Inclusive education has occupied a central role in educational planning especially over the last two decades of the 20th century. When understood broadly, the inclusive education debate concerns people who have been historically excluded from the cultural, social, and

economic benefits of formal education or of formal quality education. Brazil is a country of enormous sources of wealth as well as immense

contrasts between the rich and the poor. Discrimination and inequality have been part of the daily lives of indigenous groups, migrants, the

poor, afro-descendants, and people with disabilities and special needs (Cury, 2005). However, as stated byArtiles and Kozleski (2007), in

most countries wefind a tendency to concentrate the narrative of inclusive education on students with disabilities and special needs,

establishing a strong link with the area of special education.

In our work, the term inclusive education, or simply inclusion, refers to the provisions created for people with special educational needs or disabilities (SEND). However, it is imperative to keep in mind that this focus refers exclusively to the operational aspects of our work. The

discussion about inclusion/exclusion must not fall into reification of false or crystallized identity categories; in the real world, a student with

a disability who is poor will face greater obstacles than a student with a disability that can count on the support of a wealthy family. Inclusive education is about reducing barriers to learning and participation for all. Another common misconception is viewing the origins of

educational difficulties as arising within the learners themselves, instead of considering discriminatory practices, curricula, teaching

ap-proaches, school organization, and culture, as well as national and local policies (Booth, Nes,&StrØmstad, 2003).

We wanted to help teachers and schools create the necessary conditions for students with SEND to experience a rich, gratifying, and

successful learning process. This purpose guided the development of the virtual learning objectIncluir(the Portuguese word for the verb to

include). In this paper we present the pedagogical framework that guided its conception, the learning object in itsfinal version, and its

evaluation. Since this project is deeply rooted in years of practice in thefield of special education (mainly but not exclusively with deaf and

*Corresponding author. Tel.:þ55 5481199909.

E-mail addresses:[email protected](C. Alquati Bisol),[email protected](C.B. Valentini),[email protected](K.C. Rech Braun). Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Computers & Education

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c o m p e d u

hard of hearing children, adolescents, and adults) and in thefield of teacher education in Brazil, it is necessary to discuss some aspects regarding inclusive education in this country and our perspective on teacher education for inclusion.

1.1. Inclusive education in Brazil

Current educational policies in Brazil are guided by the concept of inclusive education. Regulatory and legal frameworks explicitly require educational authorities to aim at breaking with a history of exclusion and segregation of people with disabilities, ensuring equality of access

through mainstreaming and the provision of specialized educational services (Brasil, 2010). The factors that led the country to take this

approach are, among others, the influence of social movements for human rights, the elevated costs of maintaining two educational systems,

and international developments in the early 1990s on perspectives on inclusive education (Mendes, 2006; Michels, 2006; Rahme, 2013).

In light of its understanding of Inclusive Education (Brasil, 2008), the National Policy on Special Education aims at ensuring

main-streaming from early childhood to higher education for students with disabilities, global developmental disorders, and gifted students. The

government affirms the need of forming a political framework based on the conception of inclusive education for providing resources and

services to remove the barriers in schooling and creating specific guidelines for the development of inclusive teaching practices (Brasil,

2010).

The proportion of pupils characterized as having a disability or special educational need in mainstream systems has increased in the last

few years. According to the school census of 2012 (Brasil, 2013), the number of“included students”(the term used in the government report)

registered in regular schools has more than doubled in a period offive years (from 306,136 students in 2007 to 620,777 in 2012). However,

there are significant difficulties in the country when it comes to the implementation of such inclusive policies (Paulon, Freitas,&Pinho,

2005). A literature review of 480 articles published in Brazil between 2005 and 2010 reveals that the main difficulties for inclusion are

the lack of curricula adaptations and pedagogical resources, the lack of commitment and support from the school community, difficulties in

accepting diversity, the lack of specialized support, and the need of more resources to guarantee accessibility. Structural problems in the

educational system as a whole, such as class size, are also cited (Bisol, Stangherlin,&Valentini, 2013).

1.2. Teacher education for inclusion

In Brazil, the degree needed to qualify for primary and secondary teaching is achieved after a four-year program in universities and institutes of higher education with a focus on the development of teachers' personal, social and professional abilities, and an understanding

of teaching and learning including the process by which knowledge is constructed. In 1994, courses were recommended to include specific

units on students with special educational needs (Brasil, 1994). A unit on Brazilian Sign Language and Deaf Culture has been mandatory since

2005 (Brasil, 2005).

A national teacher training policy organizes pre-service and in-service training for teachers in the public sector. Basically, two“kinds”of

teachers are expected to deal with students with disabilities: trained teachers responsible for general education classrooms working

alongside specialized teachers responsible for organizing the resources demanded by students with special needs (Michels, 2006).

What are the obstacles and challenges that most impact Brazilian schools? An extensive report byGatti and Barretto (2011)on teachers in

Brazil gives an overview of education in the country which, in turn, allows one to understand the obstacles and challenges for inclusive education. On a broad perspective, the authors emphasize the recent expansion of basic education (real growth in terms of public networks occurring in the late 1970s and early 1980s) which generated a demand for a larger number of teachers at all levels of education. It also expressed concern about enormous regional and local heterogeneity, the urgency imposed by social transformations, and poor school

performance. More specifically in terms of teacher education, they call attention to the crystallization of curricula in courses of encyclopedic

form, the lack of reliable information that may inform how teacher education is performed, supervised, and monitored, and the generic or descriptive approaches to educational issues such as special needs. As for in-service education, they argue:

The training model often follows the characteristics of a‘cascade’model, in which afirst group of professionals is trained and these

trainees become the trainers of a new group, which, in turn, trains the next one. Through this procedure, which generally passes through the different hierarchical levels of large teaching systems, technical-pedagogical staff, supervisors and specialists, although allowing the involvement of quite high numbers of trainees in numeric terms, has proven to be far from effective when it comes to disseminating the

foundations of a reform with all its nuances, depth, and implications. (Gatti&Barretto, 2011, p. 189).

Other initiatives often seen in both the public as well as the private sector are one-shot workshops, conferences, and seminars. Although they provide interesting opportunities for gathering teachers around certain topics, questions may be raised about the duration and degree to which they are content focused and centered on transmission models. Bearing in mind that implementing inclusive education may require shifts in the way teachers perceive diversity, the way teachers think about learners, themselves, their roles, capabilities, challenges, and identities, it may be necessary to adopt different approaches to teacher education.

1.3. Teacher attitudes towards inclusion and the Learning ObjectIncluir

A systematic review byDe Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert (2011)highlights three components of teachers' attitudes towards inclusion: teachers

do not rate themselves as very knowledgeable about educating students with SEND and, in general, they are undecided or negative in their

beliefs about inclusive education; they tend not to feel competent and confident in teaching these students; and they hold negative or

neutral behavioral intentions towards students with SEND. The same study also reports that teachers with less teaching experience and

teachers with previous experience with inclusive education held significantly more positive attitudes towards inclusion. They also found

that long-term training in special needs education positively influenced the attitudes of teachers and that teachers' attitudes are related to

disability categories. A Brazilian study byGomes and Barbosa (2006)on inclusion of students with cerebral palsy found similar results:

them had more positive attitudes. Consistently, these authors reported that the participation of teachers in one-day short trainings did not

have a significant impact in their attitudes.

Considering all these issues, we sought to develop a virtual learning object (LO) to be used as a complementary tool for pre-service and in-service teacher education with large or small groups and with teachers of different levels of expertise and previous knowledge. The

literature contains many discussions about the nature of learning objects. Following remarks byWiley (2002), McGreal (2004), andParrish

(2004), we understand learning objects as digital resources designed to support learning and, thus, have a clear educational purpose. They should be accessible, searchable, and reusable, thus allowing them to be combined with other teaching resources in a variety of instructional strategies.

Our educational purpose with LOIncluiris to promote reflection about inclusion aiming at contributing for a change in the way teachers

perceive diversity and for a resignification of teachers' practice. Therefore, more than the repetition of encyclopedic information that

nowadays can be easily found on the internet, the LOIncluirintends to promote discussions around issues such as stigma, prejudice,

normality, and diversity that might help teachers to revisit their beliefs and practices. Access is free athttp://www.objetoIncluir.com.br.

1.4. Pedagogical framework of the Learning ObjectIncluir

Constructivism is the specific pedagogical framework that guided the conception and development of LO Incluir. According to

constructivist theories, the learners' actions are essential for learning. Learners build new knowledge by interacting with the world, and

considering their systems of meanings. It is also important to recall that forPiaget (1971, 1976)the previous experiences constitute the

learners' systems of meanings. The object of knowing is the subject and the world. Learning is understood as a construction and recon-struction of knowledgeda continuous movement of increasing awareness about oneself and the world.

This movement of construction and reconstruction is a dialectical exercise in which subjects modify themselves due to provocations from

the outside world (Montenegro&Maurice-Naville, 1998). When they are mobilized to think about something, triggering provocations that

destabilize their previous certainties, the possibility for learning is createddthat is, the possibility to conceptual, procedural, and attitudinal novelty. Therefore, new paths open up for the subjects.

In the case of LO Incluir, the provocations were constructed seeking possible deconstructions or destabilizations of some certainties about the possibilities and the limitations of people with disabilities, about the concepts of diversity, about teaching, and about deafness.

The cognitive imbalance generated by disturbances is what enables the advancement of knowledge. According toPiaget (1976), imbalances

are the triggers of learning and knowing and their fecundity is measured by the ability to overcome them. Many possible paths support the

reconstruction of a new equilibrium. In LOIncluir, we made use of animations, texts, images, and videos. We tried to maintain a reflective

stance by opening possibilities and not simply by providing information or reproducing concepts.

1.5. Thefinal version of Learning ObjectIncluir

Thefinal version of the LO was released in November, 2011. The homepage of the object shows an image that represents a neuron. The

image was chosen for its easy association with ideas of opening and nonlinearity: the multiple and rhizomatic connections immediately invite a free and non-hierarchical beginning and encourage further navigation. At the same time, it allows an easy aggregation of new modules as new topics of interest are developed. On the computer screen, the image moves and visual effects simulate synapses or energy exchanges.

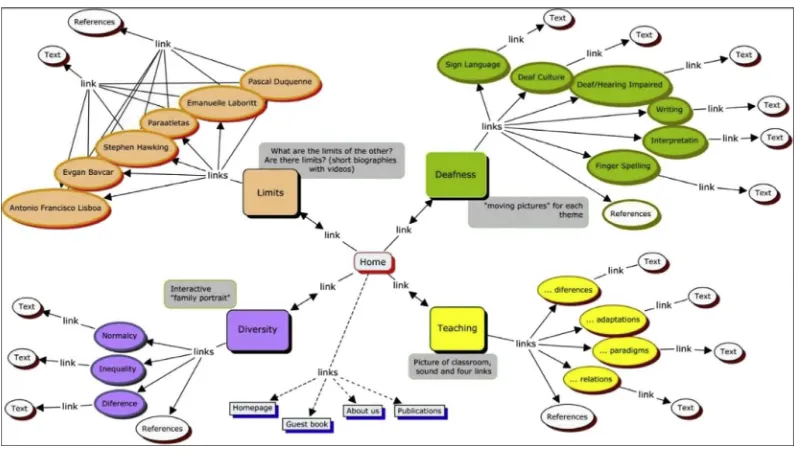

The LO is organized in four modules that integrate resources and materials (videos, animations, images, and texts) specially developed by

our team. The modules are entitled“Limits”, “Diversity”, “Teaching”, and“Deafness”. The first three modules explore general issues

regarding inclusion, and the fourth explores specific issues related to deafness, deaf culture, Sign Language, and so on.

Each of the four modules is independent from the others in terms of argument, problematization, interaction, and navigation, which allows their use separately or as required by users. However, all modules comply with the same pedagogical proposal and organization. The

final structure of the object respects the assumptions established during planning, as represented in the concept map that follows (Fig. 1):

The four modules are structured on three levels. Thefirst level was namedmobilization. Its purpose is to introduce the concepts and ideas

that will be furthered at the next level. In the second level, calledprovocation, multimedia resources such as images, sound, and text are used

to destabilize the users' preconceptions or worldviews. And in the third level, calledinformation, the user has access to information in texts

especially written for this LO.

Besides the four modules, the LO presents: a) a specific page entitled“guest book”that leads the user to the evaluation of the LO; b) a

page that provides basic information about the object and guidelines for conducting workshops with teachers; c) a page that lists scientific

publications associated with the project, and d) a page that offers information on the staff and supporters, and lists acknowledgments.

2. Learning object evaluation

It is widely accepted that the integration of computer mediated resources in distance learning or traditional classroom environments

must be evaluated. Recent studies assess the use of mobile technology (Motiwalla, 2007), gamesFurio, Gonzalez-Gancedo, Juan, Seguí, and

Rando (2013), geospatial technologies (Favier&Van der Schee, 2014), augmented reality (Zhang, Sung, Hou,&Chang, 2014), among others.

The importance of systematic evaluation of learning objects is also emphasized in the literature (Kay&Knaack, 2008; Krauss&Ally, 2005;

Nurmi&Jaakkola; 2006; Williams, 2000).Kay and Knaack (2009)state that research on the impact, effectiveness, and usefulness of learning objects is limited. Their review of evaluation of learning objects literature informs that qualitative analysis is prevalent in the form of in-terviews, written comments, email responses and think-aloud protocols. Quantitative studies have used surveys, performance data and statistics recording.

Examples allow identifying the focus of interest of recent studies.Krauss and Ally (2005)asked faculty and students to evaluate an LO

designed to help students understand the therapeutic principles of drug administration, using a rating instrument and survey

and instructors on the use and re-use of learning objects in higher education cross-discipline classroom settings. Their assessment included

learning value, added value, design usability and technology function. More recently,Baki and Çakiroǧlu (2010)looked at the use of LOs in

secondary mathematics teaching in a real classroom environment, using qualitative and quantitative data obtained from teacher and students.

We conducted a survey designed to evaluate LOIncluirin its technical and pedagogical aspects. The major goals were to determine

participants' opinions about its usability, content, and learning resource and to learn whether the LO was capable of promoting reflection on

inclusion and resignification of teachers' practice.

2.1. Method

Participants were invited to answer a questionnaire available in the link entitled “guest book”after getting to know the LO in

three different contexts: as student teachers regularly enrolled for a teacher degree, who experienced the LO as a complementary resource in a course about inclusive education; as teachers who participated in in-service trainings offered by the State Secretariat for Education, based on the LO or that used it as a complementary resource; or, as university professors working in teacher education at the same university of the respondent students, invited by email to experience and evaluate the LO. Since it is an open and free resource, other respondents might have occasionally accessed and answered the questionnaire. The questions

were adapted from the works ofDutra and Tarouco (2006), Oliveira, Nelson, and Ishcitani (2007), andVieira, Nicoleit, and Gonçalves

(2007).

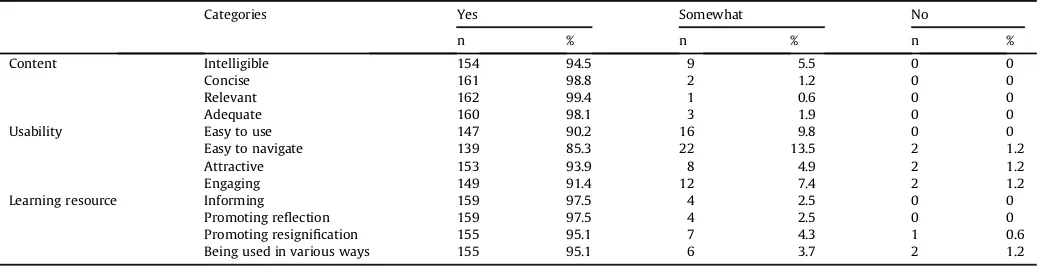

Quantitative data were gathered through 20 questions, eight of which were used to determine general characteristics of the participants. Twelve questions focused on content (intelligibility, conciseness, relevance, and adequateness), usability (easiness, navigability,

attrac-tiveness, and engagement) and learning resource (capacity to inform, to promote reflection, to promote resignification, and to be used in

various ways), allowing participants to rate “yes”,“somewhat”, or “no”. These data were analyzed using simple descriptive statistics

(proportion of subjects, percentages and average in order to summarize information).

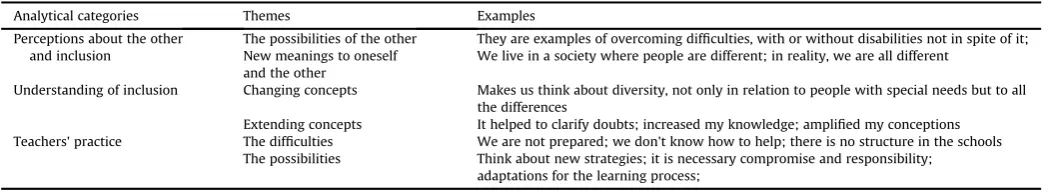

Qualitative data were generated through three open-ended questions. Participants were invited to respond if something changed the way they perceived diversity, difference, or special needs and what it could be, and if something changed how they conceived of inclusion.

Data were analyzed using thematic content analysis (Bardin, 2004) by four researchers, while two senior researchers conducted a

simul-taneous independent analysis. Analytical categories and themes were defined based on the best level of agreement reached when

comparing the results. The last question invited participants to identify what was most provocative or motivational regarding the videos,

images, texts, and animations (and they were prompted to describe, explain, suggest, or critique). A simple quantification and description of

answers was performed.

A total of 163 participants answered the questionnaire: 57% were teachers, 14% were undergraduate and graduate students, 12%

had jobs related to thefield of education, and 17% worked in otherfields. Participants reported on how they got in contact with LO

Incluir: 42% experienced it during an undergraduate course; 20% while participating in in-service training; 33% chose the alternative

“others”, and 10% did not answer to this question. The high percentage of people who chose the alternative“others”might be including

the university professors who were invited to participate by email but did not identify themselves as so. As for teachers' school level, 36% of them work in primary schools (students ages 6e14); 23% in preschool (children ages 0e6); 18% in higher education; 11% in high

school; and 12% did not answer to this question. The percentage of participants working in higher education confirms that university

professors did participate but did not identify themselves specifically in the category of participants that were invited by email.

Seventy-three percent claimed to have already had students with special needs. The average number of years of teaching experience was 12.36.

2.2. Results and discussion

Participants (N¼163) responded very positively to both the technical as well as the pedagogical aspects of LOIncluirin the close-ended

questions (Table 1):

Although all items were very positively rated, we observe that usability is the aspect that deserves a closer review, especially in terms of

user-effective navigation. This may reveal a difficulty when creating learning objects intended to invite users to a free and non-hierarchical

navigation, as mentioned in item 1.5. However, the results suggest that the problems found do not overshadow the positive qualities. The total number of participants who answered the two open-ended questions was 130. The questions were: a) has anything changed in your way of thinking about diversity, difference or special needs? Please explain; b) has anything changed in your way of thinking about inclusion? Please explain. The answers were analyzed as a unique corpus. A preliminary examination of the data was made searching for recurrent themes, which were then grouped together in three analytical categories that allowed us to understand

whether the LO was capable of promoting reflection on inclusion and resignification of teachers' practice.Table 2illustrates the process

of analysis:

The category“perceptions about the other and inclusion”consisted of answers that expressed a different way of perceiving the

possi-bilities of the people with SEND (first theme), or in the way the participant perceives him/herself and the other (second theme). In thefirst

case, we can observe that the person with SEND comes to be seen in a more positive fashion:

“For me yes, it changed my way of thinking about and admire even more those people who have certain limits. How special they are, and they make a difference. They are admirable people, their willpower is spectacular.”(P 90)

“Yes, the videos show many realities, often we do not believe what people with disabilities can do, considering that the so called“normal” people often do not have the capacity to do so.”(P 113)

“Yes. One can perceive the difficulty of the other, putting yourself in the shoes of the one who is included, you get a bigger view, and things are not easy!”(P 115)

This kind of answer reveals that the LO was an efficient instrument in provoking users to resignify the way they perceive what is

commonly seen as a disadvantage or a disability. The item named Leaning resource inTable 1also pointed that the LO is capable of

pro-moting resignification. This is important, considering that 73% percent of participants who identified themselves as teachers have already

had students with special needs. For inclusive education to be effective, changes in the expectations and beliefs teachers have about stu-dents with SEND are mandatory, as well as the capacity to thoughtfully consider the experiences of others (as very explicit in P 115).

The presence of negative attitudes like stigma and discrimination in some of the answers reinforces the need to provide teachers and student teachers the appropriate education for inclusion. This is one example of change that at the same time denotes previous negative

attitudes:“The way you see the student as a person who is capable and not as a poor thing”(P 15).

The second theme was less frequent; however, it seems very important because these participants seem to have been able to deconstruct

previous meanings attributed to oneself and the other. This kind of answer allows us to think of a deep process of reflection. Participants

seem to surpass the traditional and dichotomist organization of the world that separates the so-called“normal”individuals from the ones

that for one reason or another do notfit this group and they move to a more dialectical and complex view. The following excerpts are good

examples:

“Navigating in Learning Object Incluir, added to my previous knowledge about inclusion and my experiences in the classroom, confirm that in fact we are all different and that as a teacher we must understand that this does not necessarily make the individuals abnormal. Working with the different is the challenge for all those involved, with the need of acceptance and preparation.”(P 127)

“I realized that the subjects of inclusion are all people.”(P 88)

“We were talking/thinking on how we are apparently normal and efficient and what are our limits and what is to be efficient.”(P 124)

Navigating LOIncluir seems to have provoked questions and generated disturbances in some users' conceptions. To deconstruct

meanings previously attributed to oneself and the other, an intense cognitive movement between the subject (user) and the environment

Table 1

Technical and pedagogical aspects of LOIncluir.

Categories Yes Somewhat No

n % n % n %

Content Intelligible 154 94.5 9 5.5 0 0

Concise 161 98.8 2 1.2 0 0

Relevant 162 99.4 1 0.6 0 0

Adequate 160 98.1 3 1.9 0 0

Usability Easy to use 147 90.2 16 9.8 0 0

Easy to navigate 139 85.3 22 13.5 2 1.2

Attractive 153 93.9 8 4.9 2 1.2

Engaging 149 91.4 12 7.4 2 1.2

Learning resource Informing 159 97.5 4 2.5 0 0

Promoting reflection 159 97.5 4 2.5 0 0

Promoting resignification 155 95.1 7 4.3 1 0.6

(in this case, LOIncluir) is required. Openness to new possibilities of understanding the world involves making inferences, experiencing new

possibilities, coordinating actions, and making abstractions (Nevado, 2007; Piaget, 1987). With this, the subject builds new possibilities. In

other words, a virtualfield of possibilities is accessed and new meanings for oneself and the other may be engendered.

The second category focuses on the examination of how the object might have helped to increase the understanding of inclusion. The

first theme, named“changing concepts”, allows us to think that LOIncluirseems to have had a deep affect on changing previous ideas and

concepts. This excerpt points to very specific changes that have had an impact on this teacher's practice:

“My way of thinking about diversity, difference, and special needs changed. I was able to think about diversity, about being different, put myself facing the other, causing a change in the way of perceiving, analyzing, and reflecting as I navigated the different modules in the object. I emphasize the module about teaching. With this one, I could think of a new paradigm to myself regarding these differences, relations, and also the adjustments we face when we“try”to include these differences in our schools.”(P 36)

Most answers that could be categorized as related to understanding, however, indicate the LO has a less in-depth effectdthat is, an effect more related to extending the concepts that the subject is building, or has built, based on several previous experiences such as their teaching practice or other studies:

“By reason of being enrolled in a course on inclusion and based on the readings I've done, I had an idea regarding diversity and difference, but the Learning Object Incluir accentuated and added to my way of thinking about these issues.”(P 67)

“There was a further deepening of some thoughts about diversity, teaching, and limits. On the issue of deafness, there was a review of knowledge gained from other learning objects.”(P 151)

However, it is important to remember that this LO is not intended to be a“complete”educational experience. As stated in item 1.3, this LO

was thought to be used as a complementary tool. The pedagogical value of LOs can only be fully defined when the context of use and the

instructional arrangements are also considered (Nurmi&Jaakkola, 2006). Based on the point of view of constructivism, the context of use

and the instructional arrangements must be capable of mobilizing subjects to think, destabilize certainties and trigger provocations.

The answers grouped in the analytical category entitled“Teacher's practice”lead to a more delicate terrain. We sometimes think of

inclusion in a general, abstract manner (concepts, ideas, values, and so on). The picture is somewhat different when it comes to daily life in a classroom. Two different themes emerged, one that shows teachers thinking about new possibilities and one that shows teachers pointing

to their difficulties. The participants who answered negatively to a possible contribution of the LO to a change in the way they perceive

diversity, difference, or special needs and the way they conceive inclusion, pointed: to the difficulties that surround inclusion and to how

teachers feel inclusion was imposed on them (P 146); to the lack of structure in the schools (P 59); and confessed to a lack of preparation (P 146 and P 59). Examples are:

“Maybe it helped to raise doubts about this concept of inclusion. I say this because I have a student with moderate mental retardation and autism, and the process that is offered of inclusion makes me doubt about its effectiveness or adequacy for these students. I am not against inclusion, but I am against the way many school systems have imposed such inclusion on teachers. These students come into our classrooms with a particular diagnosis and we have minimal preparation to make a real inclusion. We still need to study hard

…

and put into practice all these learnings.”(P 146)“Despite all the valid arguments that are in the LO, after some period in teaching in a public school, I realize that the best inclusion is not inserting the person with disability in the classroom as we have today. The teacher who is there is not ready and the schools have no structure. Thinking about an ideal school, where we would have few students per teacher, then yes it would be possible to include the way it is argued in the texts of the LO.”(P 59)

Although the infrastructure can be questioned in a very practical and realistic manner (as shown in items 1.1 ad 1.2), it is also true that

many times the subjects may avoid reflecting about themselves using the strategy of blaming others (the state, the infrastructure, the lack of

economic resources, and so on). It is a way of thinking that excludes the subjects' own responsibilities. It is hard to disregard this reflection

exactly because the complaints are reasonable.

Participants that focused on the possibilities commented on the adaptations and movements needed with what it seems to be hope and willingness to change the way the school is thought of and maintained in most settings. Teachers seem to include themselves when considering the need for change:

Table 2

Analytical categories and examples of quotations extracted from the answers.

Analytical categories Themes Examples

Perceptions about the other and inclusion

The possibilities of the other They are examples of overcoming difficulties, with or without disabilities not in spite of it; New meanings to oneself

and the other

We live in a society where people are different; in reality, we are all different

Understanding of inclusion Changing concepts Makes us think about diversity, not only in relation to people with special needs but to all the differences

Extending concepts It helped to clarify doubts; increased my knowledge; amplified my conceptions Teachers' practice The difficulties We are not prepared; we don't know how to help; there is no structure in the schools

“[My ideas] have been changing for some time. As a result of navigating LO Incluir I feel that this change becomes more evident and necessary. Change that invites us to‘displace’ourselves to understand that we need to act, because our usual way of teaching no longer meets the needs of all.”(P 119)

“Yes, because one can see that the educator needs training, knowledge, insight, commitment, and responsibility for that to happen inside and outside the classroom. For me, what has changed is the view that it is necessary to have a commitment to the existing public policies.”(P 118)

“Yes, I realized that inclusion is a consequence of a quality education for all students. It provokes and requires new attitudes from the school. It is one more reason to modernize education and to [help] teachers improve their practices.”(P 42)

“I was able once again to reaffirm my idea that inclusion is being OPEN without prejudice and full of creativity andflexibility! Willing to be challenged every day because we are the result of a culture of standardization!”(P 137)

These answers also relate to the way these teachers perceive themselves as being responsible for changing attitudes. More specifically,

they illustrate a critical reflection about their teaching practice (P 119 and P 118) and a critical reflection about the school culture (P 42 and P

137). This indicates that the LO has affected participants beyond information transmission or reproduction of concepts.

The last open-ended question was answered by 99 participants, and not all of them cared to identify what was more provocative or motivational in the four aspects presented (videos, images, texts, and animations). Explicitly positive opinions were 57 regarding the videos,

58 the images, 72 the texts, and 56 the animations. Opinions classified as positive sometimes ranged from very simple answers like“the

videos are great”,“the animations are good”to more elaborate ones, such as:

“[The videos] because they were representative and also had significant information about various characters who made history.”(P 23)

“All texts are interesting and stimulating. The vocabulary is accessible, understandable and they bring practical content, without becoming a tiring or discouraging reading.”(P 50)

“The animations enable interaction which makes us better identify with the situations and subsequently we became aware of the situation. (P 29)

Criticisms and suggestions were few (six regarding the videos, texts and animations and three regarding the images). They refer to the size of the videos or their presentation format (full screen, subtitles), poor resolution, addition of controllers for pause/play/volume, or addition of other videos and stories. Participants also referred to the need for the insertion of pictures, more explanations or links in the timeline, general improvement of pictures, hyperlinks in the texts, information regarding laws, more interaction in some animations and extra explanations are referred as well. Other answers were general comments about the object or about inclusion, or answers in which participants named a video, image, text, or animation they liked but did not describe, explain, suggest, or criticize. The small number of criticisms and suggestions in this open-ended question is consistent with the positive quantitative evaluation of content, usability and

learning resource described inTable 1.

3. Conclusions

Navigability was the aspect that was not evaluated as positively as the rest. This feedback helped us to focus on improvements to facilitate effective user navigation. We reviewed all the patterns of the links aiming to avoid disorientation, repetition, and unnecessary backtracks.

We also chose more intuitive and standardized symbols, reviewed colors, and redefined the main menu. A concept map will be included in

the new version of the LO that is under construction. The view of the learning object from the perspective of the participants is extremely helpful to correct planning, design and development mistakes, and to improve items when possible.

As a complementary tool for teacher education for inclusion, LOIncluirhas proven to be a useful resource. Through the qualitative

evaluation, we were able to identify examples of movements of construction and reconstruction of knowledge. Therefore, we understand

that the pedagogical framework chosen is coherent with the aim of promoting reflection and was able to sustain the conception and

development of this LO. Learning objects might have a more pragmatic approach or have a more informative or instrumental purpose. For those situations, different learning theories or a combination of learning theories might be more appropriate.

How deep discussions will be and how far the resignification of the way teachers perceive the other and the process of inclusion will

depend greatly on how the LO is integrated in classroom or distance learning experiences in pre-service or in-service teacher education. Our work allows us to visualize one perspective on how to enhance this process.

There is no such thing as afinal answer to the challenges and dilemmas of educating teachers for inclusion. Education is complex and this

is most certainly true of inclusive education. As well, there are also complexities from one country to another and differences between regions within a country. Brazil can certainly attest to these challenges.

Two new grants from Brazilian funding agencies are allowing us to make these improvements and to develop a version of the LO

compatible with mobile devices, usinghtml5. This version will include translation into English and Spanish and two new modules, one about

physical disability and the other about intellectual disability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Donald Cochrane, University of Saskatchewan, for his writing assistance. We were supported by funding from Brazilian

Na-tional Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq, 43/2013 - MCTI/CNPq/MEC/CAPES) and State of Rio Grande do Sul

References

Artiles, A. J., & Kozleski, E. (2007). Beyond convictions: Interrogating culture, history, and power in inclusive education.Language Arts, 84, 357e364.

Baki, A., & Çakiroǧlu, Ü. (2010). Learning objects in high school mathematics classrooms: Implementation and evaluation.Computers&Education, 55(4), 1459e1469.

Bardin, L. (2004).Analise de conteúdo(3rd ed.). Lisboa: Ediç~oes 70.

Bisol, C. A., Stangherlin, R. G., & Valentini, C. B. (2013). Educaç~ao inclusiva: estudo de estado da arte das publicaç~oes científicas brasileiras em Educaç~ao e Psicologia [Inclusive

education: study of state of the art of Brazilian scientific publications in Education and Psychology].Cadernos de Educaç~ao, 44, 240e264.

Booth, T., Nes, K., & StrØmstad, M. (2003).Developing inclusive teacher education. London and New York: Routledge Falmer.

Brasil. (2013).Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo da educaç~ao basica: 2012eresumo tecnico. Brasília: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Retrieved October 21, 2014, fromhttp://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_basica/censo_escolar/resumos_tecnicos/resumo_tecnico_

censo_educacao_basica_2012.pdf.

Brasil. (2008).Ministerio da Educaç~ao. Secretaria de Educaç~ao Especial. Política Nacional de Educaç~ao Especial na Perspectiva da Educaç~ao Inclusiva. Brasília: MEC/SEESP.

Brasil. (2010).Ministerio da Educaç~ao. Secretaria de Educaç~ao Especial. Marcos político-legais da Educaç~ao Especial na perspectiva da Educaç~ao Inclusiva. Brasilia: MEC/SEESP.

Brasil. (1994).Ministerio da Educaç~ao e do Desporto. Portaria n1.793, de 27/12/94. Di

ario Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, DF, 28/12/1994. Seç~ao 1 (p.

20767). Brasília: Imprensa Oficial.

Brasil. (2005).Ministerio da Saúde. Decreto 5626/05 que regulamenta a Lei n10436 de 24 de abril de 2002. Brasília: Minist

erio da Saúde.

Cury, C. R. J. (2005). Políticas inclusivas e compensatorias na educaç ~ao basica [Inclusive and compensatory policies in elementary education].Cadernos de Pesquisa, 35(124),

11e32.

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., & Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers' attitudes towards inclusive education: a review of the literature.International Journal of Inclusive

Education, 15(3), 331e353.

Dutra, R. L. S. D., & Tarouco, L. M. R. (2006). Objetos de Aprendizagem: Uma comparaç~ao entre SCORM e IMS Learning Design. RENOTE.Revista Novas Tecnologias na Educaç~ao,

4(1), 1e10.

Favier, T. T., & Van der Schee, J. A. (2014). The effects of geography lessons with geospatial technologies on the development of high school students' relational thinking.

Computers&Education, 76, 225e236.

Furio, D., Gonzalez-Gancedo, S., Juan, M. C., Seguí, I., & Rando, N. (2013). Evaluation of learning outcomes using an educational iPhone game vs. traditional game.Computers&

Education, 64, 1e23.

Gatti, B., & Barretto, E. S. de Sa. (2011).Teachers of Brazil: Obstacles and challenges. Brasília: UNESCO.

Gomes, C., & Barbosa, A. J. G. (2006). Inclus~ao escolar do portador de paralisia cerebral: atitudes de professores do ensino fundamental [Inclusion of individuals with cerebral

palsy in school: elementary school teachers' attitudes].Revista Brasileira de Educaç~ao Especial, 12(1), 85e100.

Kay, R. H., & Knaack, L. (2008). A multi-component model for assessing learning objects: the learning object evaluation metric (LOEM).Australasian Journal of Educational

Technology, 24(5), 574e591.

Kay, R. H., & Knaack, L. (2009). Assessing learning, quality and engagement in learning objects: the Learning Object Evaluation Scale for Students (LOES-S).Educational

Technology Research and Development, 57, 147e168.

Krauss, F., & Ally, M. (2005). A study of the design and evaluation of a learning object and implications for content development.Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 1. Retrieved February 14, 2015, fromhttp://ijklo.org/Volume1/v1p001-022Krauss.pdf.

McGreal, R. (2004). Learning objects: a practical definition.International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(9), 21e32.

Mendes, E. G. (2006). A radicalizaç~ao do debate sobre inclusao escolar no Brasil [Radicalization of the debate on school inclusion in Brazil].~ Revista Brasileira de Educaç~ao,

11(33), 387e405.

Michels, M. H. (2006). Gest~ao, formaç~ao docente e inclus~ao: eixos da reforma educacional brasileira que atribuem contornosa organizaç~ao escolar [Management, teacher

training and inclusion: pivots of the Brazilian educational reform which attribute configurations to school organization].Revista Brasileira de Educaç~ao, 11(33), 406e423.

Montenegro, J., & Maurice-Naville, D. (1998).Piaget ou a intelig^encia em evoluç~ao. Porto Alegre: Artes Medicas.

Motiwalla, L. F. (2007). Mobile learning: a framework and evaluation.Computers&Education, 49, 581e596.

Nevado, R. A. de (2007).Aprendizagem em Rede na Educaç~ao a Distancia: estudos e recursos para formaç^ ~ao de professores. Porto Alegre: Ricardo Lenz.

Nurmi, S., & Jaakkola, T. (2006). Effectiveness of learning objects in various instructional settings.Learning, Media and Technology, 31(3), 233e247.

Oliveira, E., Nelson, M. A. V., & Ishitani, L. (2007). Ciclo de vida de objetos de aprendizagem baseado no padr~ao SCORM. InSimposio Brasileiro de Informatica na Educaç~ao. S~ao

Paulo: Anais do Simposio Brasileiro de Informatica na Educaç~ao.

Parrish, P. E. (2004). The trouble with learning objects.Educational Technology Research and Development, 52(1), 49e67.

Paulon, S. M., Freitas, L. B. de L., & Pinho, G. S. (2005).Documento subsidiarioa política de inclus~ao. Brasília: Ministerio da Educaç~ao, Secretaria de Educaç~ao Especial.

Piaget, J. (1971).Biology and knowledge: An essay on the relations between organic regulations and cognitive processes. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Piaget, J. (1976).A equilibraç~ao das estruturas cognitivas[The Equilibration of Cognitive Structures]. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar.

Piaget, J. (1987). O possível, o impossível e o necessario: as pesquisas em andamento ou projetadas no Centro Internacional de Epistemologia Genetica. In L. B. Leite, &

A. A. Medeiros (Eds.),Piaget e a Escola de Genebra(pp. 51e71). S~ao Paulo: Cortez.

Rahme, M. M. F. (2013). Inclus~ao e internacionalizaç~ao dos direitosa educaç ~ao: as experi^encias brasileira, norte-americana e italiana [Inclusion and internationalization of the

rights to education: the Brazilian, North American and Italian experiences].Educaçao e Pesquisa, 39~ (1), 95e110.

Schoner, V., Buzza, D., Harrigan, K., & Strampel, K. (2005). Learning objects in use:‘Lite’assessment forfield studies.Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 1e18. Retrieved February 15, 2015, fromhttp://jolt.merlot.org/documents/vol1_no1_schoner_001.pdf.

Vieira, C., Nicoleit, E. R., & Gonçalves, L. L. (2007). Objeto de Aprendizagem baseado no Padr~ao SCORM para Suportea Aprendizagem de Funç~oes. InXVIII Simposio Brasileiro de

Informatica na Educaç~ao. Anais do XVIII Simposio Brasileiro de Inform atica na Educaç ~aoeSBIE 2007(pp. 473e482). S~ao Paulo.

Wiley, D. A. (2002).The instructional use of learning objects. Bloomington, IN: Agency for Instructional Technology.

Williams, D. D. (2000). Evaluation of learning objects and instruction using learning objects. In D. A. Wiley (Ed.),The instructional use of learning objects: Online version. Retrieved February 13, 2015, fromhttp://reusability.org/read/chapters/williams.doc.

Zhang, J., Sung, Y. T., Hou, H. T., & Chang, K. E. (2014). The development and evaluation of an augmented reality-based armillary sphere for astronomical observation