Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:06

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Comparing Textbook Coverage of Lean

Management to Academic Research and Industry

Practitioner Perceptions

Kathryn A. Marley , T. Michael Stodnick & Jeff Heyl

To cite this article: Kathryn A. Marley , T. Michael Stodnick & Jeff Heyl (2013) Comparing Textbook Coverage of Lean Management to Academic Research and Industry

Practitioner Perceptions, Journal of Education for Business, 88:6, 332-338, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.721024

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.721024

Published online: 26 Aug 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 108

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.721024

Comparing Textbook Coverage of Lean Management

to Academic Research and Industry Practitioner

Perceptions

Kathryn A. Marley

Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

T. Michael Stodnick

University of Dallas, Dallas, Texas, USA

Jeff Heyl

Lincoln University, Christchurch, New Zealand

Within operations management courses, most instructors choose to devote classroom time to teaching the topic of lean management. However, because the amount of time available for instructors to devote to this topic varies considerably, there is a great deal of latitude on which specific lean tools and techniques should be discussed. The authors reflect on this issue by considering the most important practices of lean from the perspective of three stakeholders: academic research, textbook authors, and industry professionals. Based on the comparison, the authors develop a list of recommendations to help instructors who are teaching lean at the undergraduate level.

Keywords: course design, lean management, operations management textbooks

INTRODUCTION

One challenge of teaching an introductory course is develop-ing a course schedule that represents the most critical areas of learning. An introductory course in operations manage-ment (OM) is a requiremanage-ment in most undergraduate business curriculums and most OM textbooks discuss a wide array of topics. However due to time constraints, instructors must make choices on which topics to cover. Many choose topics based on what they find most interesting to teach. Others select the topics that they believe are most critical to prepare for other courses in a curriculum or for future employment. The process of course design can take a considerable amount of time and should be taken seriously to keep the content of the course interesting and relevant for students.

Correspondence should be addressed to Kathryn A. Marley, Duquesne University, Department of Supply Chain Management, 600 Forbes Avenue, Rockwell Hall 470, Pittsburgh, PA 15282, USA. E-mail: marleyk@duq.edu

One topic that is included in all introduction to OM textbooks is lean management (production). Lean manage-ment is considered a business strategy that is focused on eliminating waste, creating value, implementing specific tools/techniques, and learning how to do work in a more efficient and effective way (Shah & Ward, 2007). Several universities have developed stand-alone courses to introduce students to lean in both business and engineering curricu-lums. An overview of these institutions can be found in Blanchard, Farrington, Harris, and Utley (2009). However, because of the depth and breadth of this topic, it becomes challenging to condense the amount of lean information cov-ered within one introductory operations management course. Indeed it is often difficult to determine which lean concepts are the most salient and by necessity must be included in teaching lean. Therefore, we embark on a research study to analyze the current state of lean management across three stakeholder groups: academic researchers, textbook authors, and lean practitioners. Understanding how lean is envisioned by these three groups lays a foundation for understanding how to teach the topic of lean in the most effective way.

COMPARING TEXTBOOK COVERAGE OF LEAN MANAGEMENT 333

STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS

Academic Research

We have identified three major areas within the lean man-agement academic research stream—the bundling of lean practices into categories, the link between lean practices and performance, and the expansion of case studies illustrating successful lean implementation among service firms. Within the lean management literature, there is general agreement that there are known categories of tools and techniques, some-times called bundles, present in lean systems (i.e., Furlan, Dal Pont, & Vinelli, 2011; Shah & Ward, 2003, 2007). These include just-in-time (JIT) practices, total quality manage-ment (TQM) practices, total productive maintenance (TPM) practices, and human resource management (HRM) practices (Shah & Ward, 2003, 2007). In addition to these four cate-gories, it is essential for lean firms to develop relationships with their supply chain partners to support their continu-ous improvement efforts (Jayaram, Vickery, & Droge, 2008; Shah & Ward, 2007).

Another area of lean academic research involves examin-ing the relationship between lean (or JIT practices) and per-formance. There is empirical support that lean practices lead to improved market and business performance (Yang, Hong, & Modi, 2011), better overall performance (Furlan et al., 2011), and higher inventory turnover (Demeter & Matyusz, 2011). Other authors have examined and found relationships between JIT practices and aggregate performance measures (i.e., quality, manufacturing cost, inventory, cycle time, flexi-bility, and delivery; Mackelprang & Nair, 2010). An overview of research tying the impact of lean practices on firm perfor-mance is included in Eroglu and Hofer (2011). These studies have done an exemplary job of showing projected perfor-mance improvements through adopting lean at the tactical, operational, and strategic levels.

Lastly, the performance implications of adopting lean practices are also exemplified through the use of case stud-ies, specifically in service firms. Although the source of lean began with manufacturing automobiles (Womack, Jones, & Roos, 2007), firms in service industries are having success in applying the tenets of lean in a variety of contexts. These include applications in software services (Statts, Brunner, & Upton, 2011), healthcare facilities (LaGanga, 2011), logis-tics (Lee, Olson, Lee, Hwang, & Shin, 2008), and banking services (Wang & Chen, 2010). These case studies help read-ers contextualize lean theories and learn how to adopt lean practices in varied environments.

Summary of Textbooks

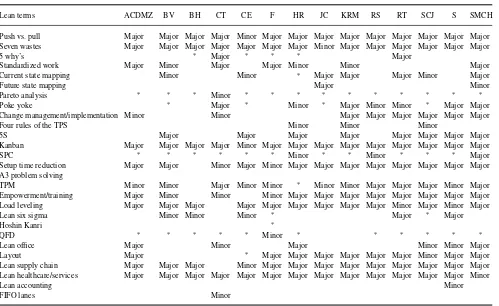

To understand the textbook coverage of lean, we analyzed a representative sample of introductory OM textbooks. The objective was to determine what content is being presented in these texts. To perform this analysis, three independent reviewers examined the textbooks and noted if and to what

extent each of a comprehensive list of lean topics was psented. Any disagreement between the reviewers was re-solved through a group discussion. The inclusion decision was quite straightforward in almost all cases as there was a high degree of correlation between reviewers with very few disagreements. When analyzing textbook coverage, it is rel-atively common to assess the degree of coverage of a topic (Kuo & White, 2004; Stambaugh & Trank, 2010) and for this project we use a relatively simple major–minor classification system. Under this scheme, if a topic was addressed with one or more paragraphs of material, it was classified as major coverage. If it was addressed in less than one paragraph it was classified as minor.

The detailed portion of the textbook analysis can be seen in Table 1 and a summary of the topics included in the lean chapter and within the textbook is included in Table 2. Most of the texts address a common set of core topics: push ver-sus pull (100% inclusion), the seven wastes (100%), kan-bans (100%), lean healthcare–services (100%), statistical process control (SPC; 100%), though not generally in the lean chapter), Pareto analysis (100%, again not generally in the lean chapter), load leveling (93%), lean supply chains (93%), setup time–batch size reduction (93%), and employee empowerment–cross training (85%). The least covered topics include future state mapping (14%), first in first out (FIFO) lanes (7%), lean accounting (7%), Hoshin Kanri (7%), and A3 (0%).

As we assess the textbook coverage of lean, three im-portant issues stand out. The first centers on the topic of kanbans. The expectation that most undergraduate students will be required to actually perform kanban calculations upon graduation is fairly low, despite the fact that every book in the analysis prominently includes kanbans. Typically this cover-age includes extended illustrations and supplementary mate-rial in the form of PowerPoint slides or videos. Beyond this, kanban calculation problems (e.g., kanban size, the number of containers to use) were the most common end of chapter exercises (10 of the 14 texts) and, when included, invariably represented the majority of the exercises.

The second issue is that several authors seem to be rely-ing on process flow diagrams, typically presented in prod-uct/process design chapters, to support their value stream mapping (VSM) content. The problem with this treatment is that process flow diagrams do not contain much of the im-portant information required for proper VSM analysis (see Rother & Shook, 2003) and are not a proper substitute. In addition, even when VSM is addressed, the development from current state to future state maps is not always de-scribed. While 57% of the texts address VSM, only 50% mentioned current state maps and only 14% described future state maps. Many authors choose to address only the basic concept of VSM. We believe this shortcoming is a major one as VSM is one of the most practical and inter-disciplinary lean tools and one that can benefit non-OM majors the most.

TABLE 1

Analysis of Textbook Coverage

Lean terms ACDMZ BV BH CT CE F HR JC KRM RS RT SCJ S SMCH

Push vs. pull Major Major Major Major Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Seven wastes Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major

5 why’s ∗ Major ∗ ∗ ∗ Major

Standardized work Major Minor Major Major Minor Minor Major

Current state mapping Minor Minor ∗ Major Major Major Minor Major

Future state mapping Major Minor

Pareto analysis ∗ ∗ ∗ Minor ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

Poke yoke ∗ Major ∗ Minor ∗ Major Minor Minor ∗ Major Major

Change management/implementation Minor Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major

Four rules of the TPS Minor Minor Minor

5S Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major

Kanban Major Major Major Major Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major

SPC ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ Minor ∗ ∗ Minor ∗ ∗ ∗ Major

Setup time reduction Major Major Minor Major Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major A3 problem solving

TPM Minor Minor Major Minor Minor ∗ Minor Minor Major Major Major Minor Major

Empowerment/training Major Minor Minor Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Load leveling Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Minor Major Minor Major

Lean six sigma Minor Minor Minor ∗ Major ∗ Major

Hoshin Kanri ∗

QFD ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ Minor ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗

Lean office Major Minor Major Minor Minor Major

Layout Major ∗ Major Major Major Major Major Major Minor Major Major

Lean supply chain Major Major Major Minor Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Lean healthcare/services Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Major Minor

Lean accounting Minor

FIFO lanes Minor

Note.ACDMZ=Anupindi, Chopra, Deshmukh, Van Mieghem, & Zemel; BV=Boyer & Verma; BH=Bozarth & Handfeld; CT=Cachon and Terwiesch; CE=Collier & Evans; F=Finch; HR=Heizer & Render; JC=Jacobs & Chase; KRM=KRajewski, Ritzman, & Malhotra; RS=Reid & Sanders; RT=Russell & Taylor; SCJ=Slack, Chambers, & Johnston; S=Stevenson; SMCH=Swink, Melnyk, Cooper, & Hartley; Major=greater degree of coverage; Minor=lesser degree of coverage;∗=the topic is not in the lean-focused chapter but is present in another chapter in the text.

The final issue relates to standardized work. Standardized work is a central tool in lean systems (Liker & Meier, 2006), yet only 50% of the textbooks include it in the lean chapter. Indeed only four of the 14 textbooks, 29%, give it major attention. The lack of textbook coverage of this topic is very surprising as standardization is one of the fundamental building blocks of lean upon which many other practices are dependent. For example, takt time, the driver of the pull system, is dependent on having standardized processes that can consistently meet time specifications.

In terms of the depth of coverage the texts provide for lean topics, there is some significant variability among them. Table 3 presents the level of coverage specifically within the lean chapter for the entire set of lean topics. As can be clearly observed, the textbook authors have made quite different decisions on the level of coverage provided in their books. When considering all the lean topics, the most exhaustive coverage is given by Swink, Melnyk, Cooper, and Hartley (2011) at 70%. Eight of the 14 texts cover more than 50% of the lean topics; the other six cover less than 50% with an average coverage of 52%.

Industry Insights

Aligning educational programs and courses with those prac-tices found within industry is becoming an increasingly com-mon and important imperative for business schools as they seek to prepare their graduates for employment. Much re-search investigates the gap between what business schools be-lieve is important to their undergraduates’ success and what potential employers are seeking (i.e., Abraham & Karns, 2009; Banerjee & Lin, 2006). One study that is critical to this research is the survey of the importance of lean practices conducted by Fliedner and Mathieson (2009). Their work is done at two different levels—a skill-based level and a tools-based level. At the skill-tools-based level, they find that employ-ers place a very high importance on human relations skills as related to lean; skills such as leadership, teamwork and change management. All of these skills have an importance rating of under 2.0 on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (highly important) to 7 (very unimportant). Interest-ingly enough, all of these HR skills are deemed more im-portant than the traditional operations and engineering skills such as process design, cellular layouts, or statistical process

COMPARING TEXTBOOK COVERAGE OF LEAN MANAGEMENT 335

TABLE 2

List of Topics and Their Coverage in the Lean Chapter and Entire Book for All Texts

Coverage in Coverage Not lean chapter book covered

Topic (%) (%) (%)

Push vs. pull 100 100 0

Seven wastes 100 100 0

5 whys 14 43 57

Standardized work 50 50 50

Current state mapping 50 50 50

Future state mapping 14 14 86

Pareto analysis 7 100 0

Poka yoke 50 79 21

Change management/implementation 57 57 43

Four rules of TPS 21 21 79

5S 57 57 43

Kanban 100 100 0

SPC 21 100 0

Setup time reduction 93 93 7

A3 0 0 100

TPM 86 93 7

Employee empowerment/training 85 85 15

Load leveling 93 93 7

Lean six sigma 36 50 50

Hoshin Kanri 0 7 93

QFD 7 71 29

Lean office 42 42 58

Layout 71 79 21

Lean supply chains 93 93 7

Lean healthcare/services 100 100 0

Lean accounting 7 7 93

FIFO lanes 7 7 93

TABLE 3

Distribution of Coverage in the Lean-Focused Chapter, by Text

All topics

Major coverage Minor coverage Total coverage

Text (%) (%) (%)

Note:ACDMZ= Anupindi, Chopra, Deshmukh, Van Mieghem, & Zemel; BV=Boyer & Verma; BH=Bozarth & Handfeld; CT=Cachon and Terwiesch; CE=Collier & Evans; F=Finch; HR=Heizer & Render; JC=Jacobs & Chase; KRM=KRajewski, Ritzman, & Malhotra; RS=

Reid & Sanders; RT= Russell & Taylor; SCJ=Slack, Chambers, & Johnston; S=Stevenson; SMCH=Swink, Melnyk, Cooper, & Hartley.

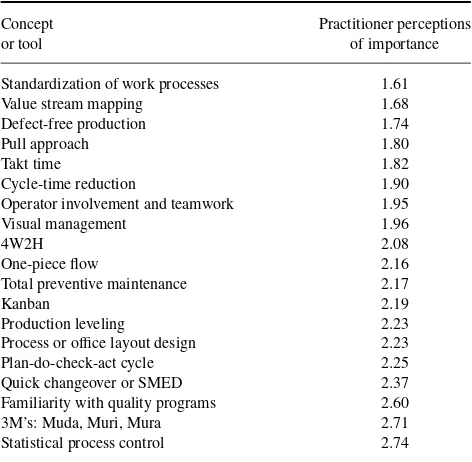

control. At the lean tools-based level, the authors find the most important skills to be standardization of work, value stream mapping, defect-free production, and push versus pull—all very conceptual type tools and practices. The more technical tools, such as kanban, production leveling, and sta-tistical process control, are deemed much less important. Because of its relevance to this study, their findings are repli-cated in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

The overall intent of this research is to provide an analysis of how lean is presented across the three stakeholder groups and to use this analysis to develop guidelines for teaching lean in the context of an introductory undergraduate OM course. Because our primary focus is on improving teaching, our comparative reference point will be the textbook authors, which we will compare to the academic research and industry survey.

Our first comparison is between the textbook authors and current academic research. Most textbook authors present the lean material as a singular collection of tools and practices and focus on the hard tools such as kanbans, takt time, and setup time reduction. Less attention is given to the softer side of lean such as employee empowerment and change management. This finding is a bit surprising given that in research looking at continuous improvement programs such as lean, six sigma, or TQM, often it is the intangible, softer sides of these programs that are a major factor in determin-ing their successful implementation (Lander & Liker, 2007).

TABLE 4

Results of Fliedner and Mathieson Study (2009)

Concept Practitioner perceptions

or tool of importance

Standardization of work processes 1.61

Value stream mapping 1.68

Defect-free production 1.74

Pull approach 1.80

Takt time 1.82

Cycle-time reduction 1.90

Operator involvement and teamwork 1.95

Visual management 1.96

4W2H 2.08

One-piece flow 2.16

Total preventive maintenance 2.17

Kanban 2.19

Production leveling 2.23

Process or office layout design 2.23

Plan-do-check-act cycle 2.25

Quick changeover or SMED 2.37

Familiarity with quality programs 2.60

3M’s: Muda, Muri, Mura 2.71

Statistical process control 2.74

Note:Responses were ranked on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (highly important) to 7 (very unimportant).

As highlighted by Spear and Bowen (1999) in their descrip-tion of the essence of the Toyota producdescrip-tion system, simply implementing lean tools and practices may not provide com-petitive advantage. They argued that lean management firms can achieve success because of the underlying way that work is designed and the way products flow through their systems. Though all the texts reviewed did address lean in health-care or services to some degree, the specific coverage of lean services within the chapters is modest and typically lacks detail. In particular, the textbooks fail to discuss how the lean production principles must be changed in order to be applied to service environments. As highlighted in aca-demic research, any firm adopting lean is likely to be facing a significant shift in operational practices, internal and ex-ternal relationships, and the core culture of the organization (Shah & Ward, 2003; Spear & Bowen, 1999; Womack et al., 2007). This shift is not going to happen without a significant amount of attention being paid to change management and implementation strategies. Yet the textbooks, with the excep-tion of Swink et al. (2011), provide little informaexcep-tion relating to these issues in either the lean chapter or anywhere else in the book.

When we compared the textbooks to the industry sur-vey we found that the textbooks tend to place much more emphasis on the technical elements and less on the con-ceptual, practice-based topics. As previously mentioned, the textbooks spend a significant amount of time covering the technical details of kanban calculations. Indeed it is interest-ing that very few of the textbooks actually provide an ap-plied conceptual example of how kanbans are implemented. Textbooks also devote large portions to the discussion of production scheduling concepts such as load leveling and mixed model sequencing. Alternatively, textbooks dedicate much less attention to the softer, more applied side of lean – the side of lean that practitioners think is most important. For example, 50% or less of the textbooks cover the topics of current state mapping, future state mapping, standardized work and the four rules of TPS—all topics that headed the list of the most important lean tools to practitioners. Also, the HR and behavioral practices that Fliedner and Mathieson (2009) found so important are not generally covered at all in the lean chapters.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The overall objective of this research is to provide some sup-port and guidance for the delivery of lean-focused material in an introductory undergraduate OM course. As a result of our analysis of the three related perspectives, we think the following comments and recommendations are in order.

1. Add supplements: Instructors should not rely simply on their chosen text itself to cover all the important material—they are going to have to supplement it.

In-structors can use Table 1 as a guide to find material in other textbooks that they think their chosen text-book is weak on. Furthermore, two online resources offer a collection of teaching material as well as fo-rums to discuss teaching lean: www.teachinglean.org and www.lean.org.

2. Be selective: Instructors should not assume that just be-cause a text discusses topics in detail that those topics are the most important ones and they must be covered thoroughly—and vice versa. This research provides a useful guide that instructors can reference when de-signing their course content.

3. Think strategic: Instructors should consider spending time on the strategic nature of lean and the higher level, conceptual tools and approaches (i.e., seven wastes, performance implications, push vs. pull). This may be accomplished through group projects where students have the opportunity to observe real-life processes, identify problems, and suggest ways that lean tools can be beneficial.

4. Map processes: Instructors should teach value stream mapping. The best textbook we found in presenting VSM is Jacobs and Chase (2010). This text provides both an exemplary discussion of VSM including cur-rent and future state mapping as well as an end of the chapter in-depth case. In addition, the practitioner-oriented bookLearning to See,by Rother and Shook (2003), is an outstanding source for supplemental material.

5. Introduce implementation strategies: Instructors should address the behavioral components of the system—standardized work, four rules of the TPS, and change management. Again, these topics are deemed important by all practitioner groups, and are under-represented in the texts. Spear and Bowen (1999) pro-vided an excellent discussion of how a lean culture is built upon standardization of job design, material flow, and informational flow and there is an excel-lent teaching note for the case that uses a clip from an

I Love Lucyepisode to apply the rules (Spear & Bowen, 2006).

6. Minimize the mechanics: Instructors should minimize the time spent on detailed, mechanistic tools and tech-niques. The primary example of this is kanbans. Rather than having students complete multiple kanban calcu-lations, instructors could actually simulate a produc-tion system using kanbans.

7. Bundle practices: Instructors should try to provide stu-dents with an idea of how the lean tools are related to each other. Academic research uses bundles such as TPM, TQM, JIT, and HRM to provide a structure for these tools. However, texts generally present the mate-rial simply as a list of practices without discussing how they are all interrelated. One text that provides a good

COMPARING TEXTBOOK COVERAGE OF LEAN MANAGEMENT 337

example of how this can be done is the Finch (2008) text, which groups the lean practices into four cate-gories: those related to inventory, capacity, facilities, and workforce.

8. Link to other chapters: Instructors should tie mate-rial from the lean chapter to other chapters within the book. This type of synthesis gives students a better context of how lean tools can provide operational im-provements in areas such as inventory management, planning, scheduling, and capacity management. 9. Make it fun: Instructors should consider using cases,

simulations, or games to show how the lean practices and principles can be applied in real-life business sit-uations. Too often it seems the texts treated the lean material as an abstract listing of practices with little re-gard for their application. For example, many authors have developed innovative games to illustrate pull pro-duction techniques (e.g., Ashenbaum, 2010; Snider & Eliasson, 2009) and general lean concepts (Fawcett & Fawcett, 2010; Swanson, 2008).

CONCLUSION

In our research, we highlight an important topic for OM in-structors to consider as they devote attention to developing detailed schedules for their core undergraduate operations management courses. Lean management is undoubtedly a topic that should be covered within a core course. However, choosing which topics to cover when faced with time con-straints has not been previously addressed. By comparing the results from our three stakeholders, it is apparent that there is some divergence between what is considered important by researchers and industry professions and what is being em-phasized within textbooks. Our research highlighted the most critical areas of difference and provides instructors with rec-ommendations on how to improve their lean teaching. As new materials are developed to help instructors teach lean more effectively, others could expand our research to include how practitioner books compare to our stakeholders. Designing an entire course around lean content would best exemplify how the lean tools and practices are pervasive within each area of operations management and how they can be integrated in an optimal manner.

REFERENCES

Abraham, S., & Karns, L. (2009). Do business schools value the compe-tencies that businesses value? Journal of Education for Business,84, 350–356.

Anupindi, R., Chopra, S., Deshmukh, S.D., Van Mieghem, J. A., & Zemel, E. (2006).Managing business process flows: Principles of operations management(2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. Ashenbaum, B. (2010). The twenty minute just-in-time exercise.Decision

Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,8, 269–274.

Banerjee, S., & Lin, W. (2006). Essential entry-level skills for systems analysts.Journal of Education for Business,81, 282–286.

Blanchard, L., Farrington, P., Harris, G., & Utley, D. (2009, October).The coverage of lean principles in higher education curricula. Paper presented at the American Society of Engineering Management Annual Conference, Springfield, MO.

Boyer, K., & Verma, R. (2011).Operations and supply chain management for the 21st century. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning. Bozarth, C., & Handfield, R. (2008).Introduction to operations and supply

chain management(2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Cachon, G., & Terwiesch, C. (2009).Matching supply with demand: An in-troduction to operations management(2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Collier, D., & Evans, J. (2007).Operations management: Goods, services and value chains(2nd ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western. Demeter, K., & Matyusz, Z. (2011). The impact of lean practices on

in-ventory turnover.International Journal of Production Economics,133, 154–163.

Eroglu, C., & Hofer, C. (2011). Lean, leaner, too lean? The inventory-performance link revisited. Journal of Operations Management, 29, 356–369.

Fawcett, S. E., & Fawcett, A. M. (2010). The PB&J challenge: Using value-stream mapping to drive learning loops.Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,8, 257–268.

Finch, B. (2008).Operations now: Supply chain profitability and perfor-mance(3rd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Fliedner, G., & Mathieson, K. (2009). Learning lean: A survey of industry lean needs.Journal of Education for Business,84, 194–199.

Furlan, A., Dal Pont, G., & Vinelli, A. (2011). On the complementarity between internal and external just-in-time bundles to build and sustain high performance manufacturing.International Journal of Production Economics,133, 489–495.

Heizer, J., & Render, B. (2010).Operations management(10th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Jacobs, F. R., & Chase, R. (2010).Operations and supply management: The core(2nd ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Jayaram, J., Vickery, S., & Droge, C. (2008). Relationship building, lean strategy and firm performance: An exploratory study in the automo-tive supplier industry.International Journal of Production Research,46, 5633–5649.

Krajewski, L., Ritzman, L., & Malhotra, M. (2010).Operations manage-ment: Processes and supply chains(9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Kuo, C., & White, R. E. (2004). A note on the treatment of the center-of-gravity method in operations management textbooks.Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,2, 219–227.

LaGanga, L. R. (2011). Lean service operations: Reflections and new direc-tions for capacity expansion in outpatient clinics.Journal of Operations Management,29, 422–433.

Lander, E., & Liker, J. K. (2007). The Toyota production system and art: Making highly customized and creative products the Toyota way. Inter-national Journal of Production Research,45, 3681–3698.

Lee, S. M., Olson, D. L., Lee, S., Hwang, T., & Shin, M. S. (2008). En-trepreneurial applications of the lean approach to service industries. Ser-vice Industries Journal,28, 973–987.

Liker, J., & Meier, D. (2006)The Toyota way fieldbook.New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Mackelprang, A. W., & Nair, A. (2010). Relationship between just-in-time manufacturing practices and performance: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Operations Management,28, 283–302.

Reid, R. D., & Sanders, N. R. (2010).Operations management: An inte-grated approach(4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rother, M., & Shook, J. (2003).Learning to see. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute.

Russell, R. S., & Taylor, B. W., III. (2011).Operations management: Cre-ating value along the supply chain. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Shah, R., & Ward, P. T. (2003). Lean manufacturing: Context, practice bun-dles, and performance.Journal of Operations Management,21, 129–149. Shah, R., & Ward, P. T. (2007). Defining and developing measures of lean

production.Journal of Operations Management,25, 785–805. Slack, N., Chambers, S., & Johnston, R. (2010).Operations management

(6th ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson.

Snider, B. R., & Eliasson, J. B. (2009). Push versus pull and mass cus-tomization: A Lego Inukshuk demonstration.Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,7, 411–416.

Spear, S. J., & Bowen, H. K. (1999). Decoding the DNA of the Toyota production system.Harvard Business Review,77, 96–106.

Spear, S. J., & Bowen, H. K. (2006).Decoding the DNA of the Toyota produc-tion system: Rules for managing self-improving work systems. Teaching Note Reference No. 5–604–086. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School. Stambaugh, J. E., & Trank, C. Q. (2010). Not so simple: Integrating new re-search into textbooks.Academy of Management Learning and Education, 9, 663–681.

Statts, B., Brunner, D. J., & Upton, D. M. (2011). Lean principles, learn-ing and knowledge work: Evidence from a software services provider. Journal of Operations Management,29, 376–390.

Stevenson, W. (2009).Operations management(10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Swanson, L. (2008). The lean lunch.Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,6, 153–157.

Swink, M., Melnyk, S. A., Cooper, M. B., & Hartley, J. L. (2011).Managing operations across the supply chain(1st ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Wang, K., & Chen, K. (2010). Applying lean six sigma and TRIZ method-ology in banking services.Total Quality Management & Business Excel-lence,21, 301–315.

Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (2007).The machine that changed the world. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Yang, M. G., Hong, P., & Modi, S. B. (2011). Impact of lean manufacturing and environmental management on business performance: An empiri-cal study of manufacturing firms.International Journal of Production Economics,129, 251–261.