Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

“Indonesian Monetary Policy”: A Comment

Stephen Grenville

To cite this article:

Stephen Grenville (2000) “Indonesian Monetary Policy”: A Comment,

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 36:3, 65-70

To link to this article:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331338963

Published online: 18 Aug 2006.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 34

View related articles

‘INDONESIAN MONETARY POLICY’:

*

A COMMENT

Stephen Grenville

Reserve Bank of Australia

There is a critical disconnect between the textbook view of how monetary policy is implemented and the practitioner ’s view. The textbook exposition builds a credit multiplier on the basis of the monetary authority’s control over money base. The ability of the central bank to control money base is never questioned—after all, the two components of money base (the public’s cash holdings and banks’ reserve balances) are part of the central bank’s balance sheet, aren’t they? Despite the near-universality of this analysis in the academic world, there is no OECD central bank that operates in this way, using money base as an operating target. The last central bank to do this—the Swiss National Bank—gave up in the mid 1980s.

Most of the time, the dichotomy between the textbook view and the practitioner’s view does not matter much. The money base model can be taught in the same way that Greek and Latin are taught, as a general discipline and exercise in logic. But sometimes the gulf between the academics and the practitioners matters, and Indonesia during the crisis was one such case. It mattered because financial markets (and others) were using the money base target (and other elements of IMF conditionality) as a measure of the commitment of the Indonesian authorities, and hence this was a key to market confidence. In January 1998, the ‘blow-out’ of money base was, along with the budget, the target of disparaging comment, with a resultant lowering of confidence and further dramatic fall in the exchange rate.

66 Stephen Grenville

I focused on the predominant component of money base—cash—and argued that the public’s demand for cash has to be met—it is ‘demand determined’. Whatever the demand for cash on a particular day, given the economic environment on that day, the authorities have to ensure that there is enough money base in the banking system to allow this demand for cash to be met. Depositors have to be allowed to withdraw their deposits if they want to. In this clear, simple and unambiguous sense, cash is always and everywhere demand determined. It is not an option for the central bank (the supplier of money base) to withhold supply— i.e. to confront the demand curve by a vertical supply curve, set at the quantity specified in the target, in the hope that the ‘price’ (i.e. the interest rate) clears the market.

The critical issue for those who claim that the authorities have direct control over money base is to explain how, day by day, the authorities could have changed the demand for cash so that money base remained close to the target. Let us explore this issue by following the events as they unfolded. The money base target set out in the initial (October 1997) agreement with the IMF envisaged money base growing by 4% over the six months to March 1998. By the end of 1997, i.e. two months into the program, money base had risen by 26% since the designated starting point of September, and the public’s cash holdings had risen by almost 20%. After only two months, the target increase had been overshot more than sixfold.

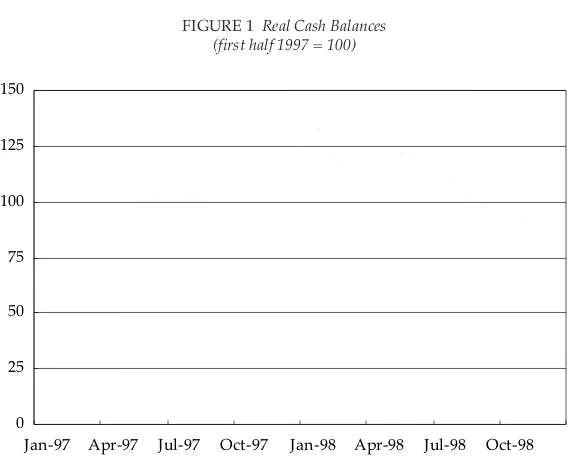

Could the authorities have prevented this? Fane argues that inflation caused the increase in the demand for cash. But that is unarguably not the case for this initial overshoot, as inflation at this stage was only 2% in this two-month period. Nor can it provide a full answer for the increased demand for cash in 1998: if it did, there would have been no rise in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) money base or real cash balances (figure 1).

FIGURE 1 Real Cash Balances (first half 1997 = 100)

This is a counterfactual, but there is a fair bit of evidence in figure 1 that the public’s demand for cash is not noticeably interest elastic (i.e. when an alternative asset such as SBIs offers an increased interest rate, this does not cause a noticeable shift out of cash). Not only did nominal cash balances increase in the latter months of 1997 and going into 1998, but real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) cash balances also increased. If real cash balances were interest elastic, they would be similarly inflation elastic— both interest rates and inflation reflect the opportunity cost of holding cash, and therefore have the same effect on demand for cash. So if cash balances were interest sensitive, we would expect to see a fall in real cash balances (compared with their pre-crisis level) in the first half of 1998, when inflation was running at an annualised rate well in excess of 100%. Instead, real cash balances were around 20–30% above their pre-crisis level. The loss of confidence in the banking system raised the public’s demand for cash, far outweighing the opportunity cost of 100%+ inflation. If this rate of inflation could not dent the public’s desire to increase their cash

0 25 50 75 100 125 150

68 Stephen Grenville

holdings, what rate of opportunity cost via SBI interest rates would have done the job? We cannot know this with any precision, but what is clear is that it would have to have been hugely greater than 100%. The same issue can be put this way: when currency runs on BCA (Bank Central Asia) and other banks in May 1998 caused currency to rise by 15% in a single month, could the authorities have stemmed the run on the banks by telling the depositors queuing up at the ATMs and tellers’ counters that they might like to hold SBIs rather than cash? Once the public is asking for its deposits to be converted into cash, then the authorities’ only choice is between facilitating this transaction and closing the bank. As we move through 1998 there is more evidence of the ineffectiveness of interest rates in influencing growth in demand for cash. Substantial increases in interest rates in May and June (to 60%) had no apparent effect in slowing the growing nominal demand, or in reducing the real demand. Real cash balances fell in July and August, coinciding with the peak in SBI interest rates, but they fell just as fast in October and November, despite substantial falls in the SBI interest rate. In short, it is hard to detect any effect of SBI interest rates on the demand for real cash balances, let alone an effect potentially big enough—and fast-acting enough—to contain the rise in real and nominal cash balances.

bankrupt companies never makes much sense at any interest rate, so it is hard to evaluate what was happening to bank lending in 1998 in commercially rational terms. But it is harder still to argue credibly that SBI interest rates of, say, 60 or 70% (as achieved later in 1998) would have caused much substitution of SBIs for loans, when these loans were being made for non-commercial reasons—i.e. to related companies facing imminent bankruptcy or, like Texmaco (Fane 2000a: 29–30), under instruction from the President.1

I should also respond to the claim that there is some inconsistency between my criticism of money base targeting and my advocacy of higher interest rates in the last months of 1997 and early months of 1998. Not only is this consistent, but it is the heart of the argument: interest rates of 50% or so might well have been appropriate for the period and would have helped the exchange rate, but would not have been enough to keep the demand for base money to its target.

One point, minor in itself, is symptomatic of the degree of disconnect in the debate: Fane misquotes me as saying that the US used money base targeting. What I said was that they targeted bank liquidity until a decade or two ago. The difference is central to the argument between us. If the authorities are targeting bank liquidity (i.e. banks’ reserve balances), they are doing this in the recognition that the other component of base money—cash—is ‘demand determined’.

There are other matters of disagreement, but perhaps to mention one will be enough. In quoting with approval the Korean and Thai experience with money base, Fane fails to mention that money base in both countries, targeted in the IMF programs to increase, actually decreased. Targets are there to be met, not to be re-interpreted as ceilings—a money base approach should be just as concerned about an undershooting as it would be about an overshooting. But recognition of this would require Fane to concede the basic point—that control over money base is so imprecise and uncertain as to make it an unsuitable guide for policy.

NOTE

* Fane (2000b), pp. 49–64 of this issue.

70 Stephen Grenville

REFERENCES

Fane, George (2000a), ‘Survey of Recent Developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (1): 13–44.

—— (2000b), ‘Indonesian Monetary Policy during the 1997–98 Crisis: A Monetarist Perspective’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (3): 49–64, in this issue. Grenville, Stephen (2000), ‘Monetary Policy and the Exchange Rate during the

Crisis’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (2): 43–60.

RAND Indonesia Data

Documentation Core

The RAND Labor and Population program, with support from its Popu-lation and Development Center Data Cores, has compiled an extensive set of documentation for Indonesian Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) survey-based data.

This documentation includes English and Indonesian versions of the questionnaires used in most of the nationally representative surveys conducted by CBS from the early 1980s to the present, readily accessible through Web-browsers/Adobe Acrobat. The documentation also includes interviewer manuals and other essential survey documentation.

Current documentation coverage includes the National Socio-economic Surveys (Susenas), the National Labor Force Surveys (Sakernas), Large & Medium Manufacturing Industry Statistics, Rural and Urban Price Data, Village Potential Statistics (Podes), Inter-Censal Population Surveys (Supas), Estates Wages, Special Household Savings and Investment Surveys (SKTIR), and portions of the Agricultural, Economic and Population Surveys.

For more detailed information, see: