Sugeng Riyanto

Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Padjadjaran Sumedang and Dutch Language CenterErasmus TaalcentrumJakarta email:sugeng.riyanto@unpad.ac.id; sugengriyanto@erastaal.or.id

Introduction

This article tells about sentences of Dutch-Indonesian interlanguage of Indonesian students that are in process of learning of Dutch as a second language. It is a psycholinguistic study that is based on the Processability Theory (Pienemann 2006 en 2007).Interlanguageis a language system that is developed in the heads of language learners (Richards and Schmidt 2002: 267, O’Grady and Archibald 2005: 401, Wray and Bloomer 2006: 54, Tarone 2000: 182, Tarone 2006: 747). Elis and Barkhuizen (2005) named it alearner language. The reasearch questions are about: (1) the types of the interlanguage sentences; (2) the level of acquisition; (3) the prediction of the Processability Theory; (4) the stadium of interlanguage. The study tries to challenge the prediction of the theory, especially about the syntactical proficiency.

Processability Theory

The Processability Theory (hence PT) is a theory about development of second language (L2) acquisition by the learners. According to the theory L2-learners can produce and understand linguisctis items that can be processed in a given time by the language processor in the mind. Therefore it is important to know the structure of the language processor and how does the processor process the L2. In that way we can predict the development of L2 acquisition of the learners concerning the production en the comphrehension (Pienemann 1998a, 1998b, 2005, 2006, 2007, Jordan 2004, VanPatten and Williams 2007, Alhawary 2009, Riyanto 2010).

The PT aims to develop hypothesis about the universal hierarchy of several means in the processing of a language concerning the procedural skill that is necessary for the processing of the learning language. The process is executed by the language processor in the mind of the L2-learners (Pienemann 2005:3). Thus people can predict an verify the stadium of the L2-acquisition.

The structure of the language processor is responsible for the language processing in real time and is determined by psycholinguistic factors as the retrieving of words from mental lexicon en from the working memory. Research on the L2-acquisition takes also the language processor in to account, so that one has to pay attention to the psycholinguistic factors that influence the processing of a language, inclusive of the L2.

1

The PT proposes a hierarchy in the language processing in the mind of language learners (processing herarchy). The hierarchy is based on the idea that there is a grammatical information exchange between phrases in a sentence (Pienemann 1998a, 2005). The grammmatical information ‘third person singular’ is given tode kleine Peter(the little Peter) and gaat(goes) in the sentenceDe kleine Peter gaat naar de bakker(The little Peter goes to the bakery). There is a matter of agreement between the subject en the predicate. According to the Lexicale Functionele Grammatica (LFG) and de theory of Levelt (1989) about language production, the language processor scans whether for intancede kleine Peter and gaat contain the same grammatical information. If the information match each other then the phrases can fulfill the syntactic function in the sentence. The L2-learners have not sometimes any control to the grammatical informations between phrases. There is also grammatical information exchange within a phrase: twee(two) (grammatical information: plural); it needs a plural noun in a nominal phrase (i.e. boeken ‘books’). Thus twee boek (two book) is interlanguage. Noun phrase like een mooi auto (a beautiful car) is interlanguage because the article of auto is de. It should be een mooie auto. There is also a matter of grammatical exchange within a nominal phrase. The LFG calls it the process of feature unification. The feature unification between phrases needs more processing than that within a phrase and therefore the first mentioned has a higher position in the processing hierarchy.

The proces of grammatical agreement passes a fixed sequence. That is the principle of the processing hierarchy. The nominal phrase is for instance composed before the verbal phrase. A woord is a category, i.e. ‘noun’, ‘verb’, etc., and the categorial procedure is the place of the grammatical information as ‘singular’, ‘past, etc.. That’s why the categorial procedure comes before the procedure of the nominal phrase. This is the first version of the processing hierarchy (Pienemann 1998a, 2005):

1. No rocedure: e.g., producing a simple wordja(yes).

2. Categorial procedure: e.g., adding a past-tense morpheme to a verb -te for werkte(worked).

3. Nominal phrase: e.g., matching plurality as intwee woorden(two words). 4. Verbal phrase procedure: e.g., moving an adverd out of the verb phrase to the

front of a sentence: e.g.,Morgen ga ik naar Leiden(Tomorrow I go to Leiden). 5. Sentence procedure: e.g., subject-verb agreement: ik ga (I go), hij gaat (he

goes),wij gaan(we go).

6. Subordinate clause procedure: e.g., use of subjunctive in subordinate clauses triggeed by information in a main caluse:Ik zeg dat hij morgen naar Leiden gaat (I say that I go to Leiden tomorrow).

the next procedure; and (b) the hierarchy mirrors the time-course in language generation (Pienemann 2007:141). Therefore the learner has no choice other than to develop along this hierarchy. Phrases cannot be assembled without words being assigned to categories such as “noun” and “verb,” and sentences cannot be assembled without the phrases they contain and so forth. The fact that learners have no choice in the path that they take in the development of processing procedures follows from the time-course of language generation adn the design of processing procedures. For example, if learners are in stage 3 of pocessing (they can only exchange information in a phrase), they find problems to produce a sentence, because they have to exchange grammatical information between phrases.

De Informanten en de Taaldata

De informanten bestaan uit studenten van Vakgroep Nederlands Universitas Indonesia. In mei 2007 hebben ze het examen van het Certificaat Nederlands als Vreemde Taal (CNaVT) gedaan. Ze zaten toen op de tweede, vierde, zesde, en achtste semester. In het onderzoek is de groepsvorming niet gebasseerd op hun semesters maar wel op de profielen van het CNaVT-examen, namelijk PTIT (toeristisch profiel; A2), PMT (maatschappelijk profiel; B1), en PTHO (hoger onderwijs profiel; B2). Er kwamen tien informanten in aanmerking voor ieder profiel. De keuze is gebasseerd op hun examenresultaat, zowel zwakke, gemiddelde, als sterke informanten.

De data bestaan uit gesproken materiaal van het CNaVT-examen, het zogenaamde C-gedeelte. De afname van het examen is in mei 2007 gedaan door docenten van Universitas Indonesia en docenten van het Erasmus Taalcentrum op het Erasmus Taalcentrum Jakarta gedaan. De opname is opnieuw manueel opgenomen op het hoofdkwartier van het CNaVT in de Katholieke Universiteit Leuven op eind september 2009.

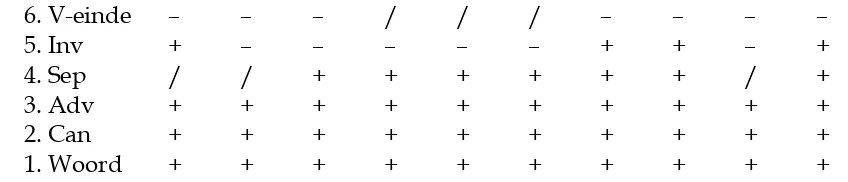

De theorie maakt gebruik van de zogenaamde implicationele schaal om onderzoeksresultaten te presenteren (Pienemann 1998a en 2005b). Met de schaal kan men de ontwikkeling van syntactische vaardigheid (de vaardigheid in de woordvolgorde van de zinnen) van de T2-leerders voorspellen. De V-einde constructie is bijvoorbeeld de moeilijkste constructie om te verwerken in de hoofden van de taalleerders in vergelijking met de andere constructies. Als ze de constructie heeft verworven (in de kolom ziet men een ‘+’), dan hebben ze de andere makkelijkere constructies ook verworven. In de onderstaande kolommen moeten dus ook plus-tekenjes staan. De plus-tekentjes houden in dat de genoemde constructies verworven zijn (minimaal 70% goed). De tussentaal is in ontwikkeling, dus men streeft niet naar een hoger percentage.

De Verwerving van de Constructies 1. Één woord constructie

De constructie bestaat maar uit één woord. Alle informanten beheersen deze gemakkelijkste verwerkbare constructie. In de constructie verwerken ze alleen woorden en de grammaticale elementen hebben ze niet nodig. De grammaticale elementen hebben ze pas nodig als ze minimaal een woordgroep vormen. Ze beschikken dus al kennis dat een zin minimaal uit een S en een PV bestaat. Ze zijn volwassen T2-leerders die bijna zeker andere vreemde talen hebben geleerd. Ze hebben het Nederlands intensief geleerd in de vakgroep van ervaren docenten. Als ze toch één woord constructie uitten dan was het meestal: ja/nee. Dat is normaal bij het antwoord van een ‘ja/nee’-vraag.

2. Canonische constructie

De canonische constructie heeft de volgende volgorde: S-PV-(O)-(Bep). Minimaal heeft de zin een S en een PV. Deze constructie is moeilijker te verwerken dan de eerst genoemde. De taalverwerker in het hoofd van de leerder moet minimaal een nominale groep verwerken (voor de syntactische functie S en O) en een verbale groep (voor het gezegde). De taalverwerker weet ook de grammaticale informatie tussen woorgroepen te uitwisselen: eerst binnen de groepen en daarna tussen de groepen. De woordvolgorde is het eenvoudigst omdat de agens vóór de daad (in de vorm van een verbum) staat terwijl de agens daarop volgt. Die volgorde is ongemarkeerd. Daarom kunnen de informanten de canonische constructie verwerken.

In tussentaalzin (1) probeert de informant te vertellen dat haar trui gekrompen is. Blijkbaar kent zij het woord niet en ten onrechte kiest zeverkleinen. Ze zou beterkleiner wordenkiezen.

(1) Het is verkleinen. (PMT 4) (profiel PMT, informant 4)

S PV

3. Adv-constructie

De structuur van Adv constructie is: Bep/O-S-VF/P-(O)-(Bep). De verwerking van deze constructie is een stuk moeilijker dan de canonische omdat er sprake is van gemarkeerdheid. Het op de eerste plaats staande zinsdeel is geen S, maar bijvoorbeeld een Bep of een O. Er is sprake van een topicalisatie. De constructie is echter een tussentaalsconstructie omdat het S vóór de PV/P blijft staan. De goede volgorde voor die structuur is de Inv-structuur, namelijk de inversiezinnen waarin het S achter de PV/P staat. De informanten beheersen de Adv-constructie. Het Indonesisch heeft ook zulke volgorde. Hieronder ziet men een voorbeeld van de tussentaalzin:

(2) De eerste ik heb gegevens over de meest gebruikte communicatiemiddel in

Bep S PV

4. Sep-constructie

De zin in de separabel constructie heeft meer dan één werkwoord. Het predicaat bestaat uit een PV en één of meer rest van gezegdes (RG). Wat de betekenis betreft, horen de werkwoorden bij elkaar, maar in de zin staan ze gescheiden. De PV staat naast het S. De betekenis en de vorm stemmen niet overeen en daarom is de constructie moeilijker te verwerken dan de vorige constructies. Als voorbeeld neemt men de volgende tussentaalzin:

(3) Vandaag moet ik fietsen in zee. (PTIT 2)

Bep VF S RG

De PV en het RG staan wel gescheiden maar niet zo ver. Het is normaler als het RG achter in de zin staat. Men fietst ook nooit in zee. Zin (3) kan men veranderen bijvoorbeeld in zin (3a).

(3a)Vandaag wil ik langs (de) zee fietsen.

K VF S RG

Zin (4) is tussentaal door het gebruik van tussenwerpsel ja. In het gesproken Indonesisch is het gebruik van tussenwerpsels erg normaal. Indische Nederlanders gebruiken ook vaak tussenwerpsels in hun Nederlands om een apart sfeer te creëren. In het Nederland kan men de zin (4) veranderen in bijvoorbeeld (4a).

(4)Dus ik kan niet ruilen, ja. (PMT 1)

S VF RG

(4a)Mag ik dus de trui niet ruilen?

VF S RG

5. Inv-constructie

Deze constructie lijkt op Adv-constructie. Het verschil ligt bij de positie van het S. Bij de Adv-constructie staat het S vóór de PV en bij de Inv-constructie staat het S achter de PV. De Adv-constructie is tussentaal terwijl de Inv-constructie een goede Nederlandse zin is. Inv is de afkorting van inversie. De verwerking van Inv-constructie is moeilijker dan Sep-constructie omdat een deel van de verbale groep, bijvoorbeeld een bepaling, in de eerste plaats staat in de zin en het S moet zich verplaatsen naar de plaats achter de PV. Er is sprake van een topicalisatie. De woordvolgorde van zin (5) is structureel goed maar de zin bljift tussentaal want hij heeft nog aanpassingen nodig om een goede Nederlandse zin te worden (5a).

(5)In de slaapkamer staat een twee bed. (PMT 1)

Bep VF S

(5a)In de slaapkamer staan er twee bedden.

Bep VF Sv S

Zin (6) heeft een Adv-constructie want het S staat vóór de PV. De goede volgorde ziet men bij inversiezin (6a).

(6) Misschien het is toch genoeg…. (PTHO 6)

Bep S VF

(6a)Misschien is het toch genoeg….

Bep VF S

6. V-einde constructie

Deze bijzinsconstructie is volgens de PT de moeilijkste constructie om te verwerken. Semantisch horen het subject en het gezegde bij elkaar maar in de bijzin staan ze ver uit elkaar. Het ver uit elkaar zetten van de zinsdelen is een moeizaam proces in het geheugen. Het Indonesisch kent het taalfenomeen niet en Engels evenmin. Indonesisch is een SVO taal en de informanten hebben Engels geleerd die ook een SVO taal is. Er is sprake van SVO-fanatisme in de hoofden van Indonesiërs. In de Sep-constructie wordt er één woordgroep gescheiden terwijl er bij V-einde constructie twee woordgroepen worden gescheiden. Soms lukt het wel bij de informanten om het subject en het gezegde te scheiden maar de gesproken zin wordt niet altijd een goede Nederlandse zin zoals bij (7). In het Indonesisch isnaar daar(ke sana) normaal.

(7) …als we naar daar gaan, …. (PTHO 3)

konj S VF

(7a) …als we daar naartoe/ernaartoe gaan, ….

konj S VF

Bijzin (8) begint met met een voegwoorddat en de PV moet dus achter in de zin staan dichtbij het rest van het gezegde en ver van het subject. De PV is kunnen in plaats van kan want het subject is de mensen. Als alles geregeld is dan leest men zin (8a). De Sep-constructie mag zich niet voordoen bij een bijzin maar de informant PTHO 4 houdt niet aan de regel. Hij kiest voor de Sep-constructie. Dat heeft hij ook gedaan bij twee andere tussentaalzinnen.

(8) …dat mensen kan zelf kiezen…. (PTHO 4)

konj S VF RG

(8a) …dat de mensen zelf kunnen kiezen….

konj S VF RG

De Implicationele Schaal

In Tabel 1 ziet men het resultaat van de implicationele schaal van PTIT. Tabel 1: De implicationele schaal van PTIT

6. V-einde – – – / / / – – – –

5. Inv + – – – – – + + – +

4. Sep / / + + + + + + / +

3. Adv + + + + + + + + + +

2. Can + + + + + + + + + +

1. Woord + + + + + + + + + +

Toelichting: 1 = informant PTIT 1; 2 = informant PTIT 2; enzovoort.

Uit Tabel 1 ziet men dat vier informanten de Inv-constructie beheersen. Informant PTIT 1 beheerst Inv wel maar Sep niet want hij produceert minder dan vier Sep-constructie (vandaar ziet men “/”) zodat er niet bepaald kan worden of hij de consructie beheerst. Als hij de constructie niet beheerst dan ziet men “–” en als men onder een plus-tekentje een minus-tekenje ziet dan wordt de theorie onwaar. Het tekentje “/” stelt de theorie in veiligheid.

De informanten bij PMT presteren beter dan die van PTIT. Zes informanten beheersen Inv en Sep is mooi gevuld met plusjes in de implicationele schaal. Informant PMT 1 doet iets raars want hij produceert minder dan vier zinnen met Adv-constructie zodat men niet kan bepalen over zijn beheersing van de constructie. De informant heeft de theorie in veiligheid gesteld. In de implicationele schaal bij PMT zijn er nog vier “/”-tekentjes.

De implicationele schaal van PTHO is het mooist gevuld. Men ziet geen “/” meer. De PTHO-informanten produceren meer zinnen dan de andere groepen informanten. Hun prestatie is toch bijna hetzelfde als PMT. Ze beheersen Sep-constructie goed. Vijf informanten beheersen Inv. Één informant beheerst V-einde.

De Volgorde van de Beheersing

In Tabel 2 ziet men de positie van iedere informant wat hun syntactische vaardigheid betreft. Er wordt rekening gehouden dat ze minimaal vier zinnen in iedere constructie produceren .

No. Informant Percent Semester No. Informant Percent Semester

1 PTHO 1 86,53 4 16 PMT 6 59,26 4

2 PMT 9 79,17 6 17 PMT 10 53,68 6

3 PTHO 9 74,99 6 18 PTIT 5 51,67 2

4 PMT 5 74,44 4 19 PMT 4 50 6

5 PTHO 8 72,22 4 20 PTHO 7 49,72 6

6 PMT 3 71,69 6 21 PTIT 3 49,17 2

7 PTHO 5 69,87 4 22 PTHO 4 45,83 4

8 PTIT 7 66,89 6 23 PTIT 6 43,33 2

9 PTIT 10 65,09 6 24 PTIT 4 38,89 2

10 PTIT 8 65 2 25 PTHO 10 38,15 4

11 PMT 7 62,50 2 26 PMT 2 35,35 4

12 PTHO 6 62,33 6 27 PMT 1 33,33 6

13 PTHO 3 62,24 8 28 PTIT 2 27,94 4

14 PMT 8 61,11 8 29 PTIT 1 25 2

15 PTHO 2 60 6 30 PTIT 9 19,85 4

Zes informanten (drie PTHO en drie PMT) beheersen meer dan 70%. Ze zijn het best bij de verwerking van de drie constructies. Onder hen zit geen informant van PTIT. Bij tien van de besten zitten er drie informanten van PTIT. De informanten van PTIT domineren wel bij tien laagste percentage waaronder ook twee informanten van PTHO en twee informanten van PMT zitten. Er wordt hier alleen gekeken naar de goede volgorde van het subject en de PV/het gezegde.

Conclusie

The results of the study provide evidence for the correctness of Pienemann’s theory. Learners who have acquired sentences with the highest level of processing will also already have acquired sentences with a lower level of processing. The results from learners with a high level of proficiency in Dutch verify the processability theory with more certainty than the results of learners with a lower proficiency. Learners tend to rely on meaning if they are not confident of their grammatical proficiency. Interlanguage is the result of the immediate need to encode in the mind concepts and ideas into the form of linguistic items, within a fraction of a millisecond, whilst the supporting means are limited, and whilst learners already have acquired a first language and possibly another language as well.

The same result is found by Het resultaat stemt overeen met het onderzoek van bijvoorbeeld Kawaguchi (2005) naar tussentaal Japans-Engels, Mansouri (2005) naar tussentaal Arabisch-Engels, Zhang (2005) naar tussentaal Chinees-Engels, en Håkanson (2005) naar tussentaal Syrisch, Zweeds-Karamanji, Zweeds-Turks, Zweeds-Arabisch bij kinderen.

de vorm en de betekenis zodat de informanten het woord makkelijk verwerken. Met andere woorden er is sprake van een mapping tussen de vorm en de betekenis.

De aanpassing van de grammaticale informaties tussen de woorden en tussen de woordgoepen blijft bij de informanten een struikelblok. Bij de tussentaalzinnen worden de grammaticale informaties niet altijd uitgewisseld. Om goede Nederlandse zinnen te worden moeten ze rekening houden met de juiste uitwisseling van de grammaticale informaties. Bij de begin fase van de tussentaal letten de taalleerders meer op de betekenis dan op de grammatica. De betekenis moet uitgedrukt worden door middel van talige elementen en de grammatica maakt de ordening van de betekenis doelmatig en doeltreffend. Riyanto (1990) heeft onderzocht dat Indonesiërs die Nederlands beheersen meer op de betekenis letten dan de grammatica terwijl de eerste taal sprekers van het Nederlands het omgekeerde hebben gedaan.

De Processability Theorie speelt veel te veilig. De theorie bepaalt het percentage van 70% als minimale beheersing bij Sep, Inv, en V-einde. Met zo’n percentage is het moelijk om de theorie uit te dagen. De theorie moet open stellen voor een hoger percentage, bijvoorbeeld 80%. Met een hoger percentage zal het resultaat van het onerzoek er anders uitzien. De theorie past dus eerder bij beginnende taalleerders. Voor de gevorderden of near native heeft men een veel hoger percentage, bijvoorbeeld 90%. Dat is een uitdaging voor een verder onderzoek.

Onderzoeken naar tussentaal inspireren de mensen om niet negatief te oordelen over taalproducten van tweede taalleerders. Negatieve reacties op de tussental passen hierbij ook niet. De docenten en leraren mogen de leerders zeker niet ontmoedigen. Ze moeten de leerders juist aanmoedigen. De zinnen die ze produceren hebben een ingewikkeld proces doorgelopen in hun hoofden. Ze hebben een beperkte tijd om alles te verwerken. Hun woordenschat is nog beperkt en ze kennen ook nog weinig grammaticale regels. De tussentaal is het resultaat van de noodzaak bij de leerders om in een snelle tempo ideën en concepten uit te drukken in talige elementen terwijl ze nog een beperkte woordenschat en een beperkte grammatica hebben en ze de eerste taal of een vreemde taal al hebben. Dat ze toch iets kunnen zeggen in de tweede taal in welke vorm dan ook moet men accepteren als een geweldige prestatie. Ze hebben in hun hoofden veel moeite gedaan.

Bibliografie

Håkanson, G. 2005. “Similarities and differences in L1 and L2 development,” in M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Processability Theory.

Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 179─197.

Kawaguchi, S. 2005. “Argument structure and syntactic development in Japanese as a second language,” in M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Procesaability Theory. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 253─298. Kridalaksana, H. 2008. Kamus Linguistik. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. Mansouri, F. 2005. “Agreement morphology in Arabic as a second language,” in

M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Processability Theory.

Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 117─153.

O’Grady, W., J. Archibald, M. Aronoff, and J. Rees Miller. 2005. Contemporary Linguistics: An Introduction. New York: Bedfort/St. Martins.

Pienemann, M. 1998a. Language Processing and Second Language Development: Processability Theory.Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pienemann, M. 1998b. “Developmental dynamics in L1 and L2 acquisition: Processability Theory and generative entrenchment.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(1), 1─20.

Pienemann, M. and G. Håkansson. 1999. “A unified approach towards the development of Swedisch as L2: a processability account.” Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 383─420.

Pienemann, M, B. Di Biase, and S. Kawaguchi. 2005. “Processability, typological distance and L1 transfer,” in M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Procesaability Theory. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 85─116. Pienemann, M. 2005a (ed.). Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Procesaability Theory.

Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Pienemann, M. 2005b. “An introduction to Processability Theory,” in M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Processability Theory.

Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1─60.

Pienemann, M. 2005c. Discussing PT, and M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Processability Theory. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins,

61─83.

Pienemann, M. 2006. “Language processing capacity,” in C.J.Doughty and M.H. Long (eds.) The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Maden, MA:

Blackwell, 679─714.

Pienemann, M. 2007. “Processability theory,” in B. VanPatten and J. Williams (eds.), Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction. Mahwah, NJ, London: Lawrence Erlbaum,137─154.

Richards, J.C. and R. Schmidt. 2002.Longman Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. Harlow, London: Perason Education Limited.

Riyanto, S. 1990. “Syntactische en semantische middelen bij de interpretatie van Nederlandse zinnen.” MA-thesis Universiteit Leiden.

en K. Groeneboer (eds.) Empat Puluh Tahun Studi Belanda di Indonesia; Veertig Jaar Studie Nederlands in Indonesië. Depok: Fakultas Ilmu

Pengetahuan Budaya Universitas Indonesia, 247─266.

Riyanto, S. 2011b. “Basantara Belanda-Indonesia: Kajian Psikolinguistik pada Tataran Sintaksis.” Disertation. Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya Universitas Indonesia.

Selinker, L. 1972. “Interlanguage.” International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 10, 1972: 209─231.

Selinker, L. and D. Douglas. 1985. “Wrestling with ‘context’ in interlanguage theory.”Applied Linguistics vol. 6 no. 2: 190─202.

Selinker, L. 1988. “Papers in interlanguage. Seameo Regional Language Centre, Occasional Papers” no. 44, January.

Selinker, L. 1997. Rediscovering Interlanguage. London : Longman.

Selinker, L. and U. Lakshmanan. 1992. “Language transfer and fossilization: the ‘Multiple Effects Principles’”, in S. Gass en L. Selinker (eds.) Language Transfer in Language Learning. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 197─216.

Tarigan, H.G. 1988.Pengajaran Pemerolehan Bahasa. Bandung: Angkasa.

Tarigan, H.G. and D. Tarigan. 1988. Pengajaran Analisis Kesalahan Berbahasa. Bandung: Angkasa.

Tarone, E. 2000. “Still wrestling with ‘context’ in interlanguage theory.”Annual Review of Applied Linguistics20: 182-198.

Tarone, E. 2006. “Interlanguage,” in K. Brown (ed.)Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Oxford: Elsevier, 747─752.

Wray, A. and A. Bloomer. 2006. Projects in Linguistics: A Practical Guide to Researching Language. New York, Londen: Hodder Arnold.

Zhang, Y. 2005. “Processing and formal instruction in the L2 acquisition of five Chinese grammatical morphemes,” in M. Pienemann (ed.), Cross-Linguistic Aspects of Processability Theory. Amsterdam: John