Sonia Royo is senior lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the University of Zaragoza, Spain. She participates in the research team led by Lourdes Torres in accounting, management, and auditing of public sector reforms (http:// gespublica.unizar.es). Her primary research interests are in the fi elds of e-government and citizen participation. She has published articles in leading international journals, such as Public Administration, International Public Management Journal, and Government Information Quarterly.

E-mail: sroyo@unizar.es

Basilio Acerete is senior lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the University of Zaragoza. He participates in the research team led by Lourdes Torres in accounting, management, and auditing of public sector reforms (http://gespublica. unizar.es). His research interests are concerned with citizen participation and public–private partnerships. His articles have been published in top referenced jour-nals, and he has been a visiting researcher at the University of Manchester.

E-mail: bacerete@unizar.es

Public Administration Review, Vol. 74, Iss. 1, pp. 87–98. © 2013 by The American Society for Public Administration. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12156.

Ana Yetano is senior lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the University of Zaragoza and belongs to the Gespública research group (http:// gespublica.unizar.es). Her research interests include citizen participation, performance measurement and management in the pub-lic sector, and pubpub-lic sector accounting. She has published in international journals such as Public Administration, European Accounting Review, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, and Public Performance and Management Review.

E-mail: ayetano@unizar.es Sonia Royo

Ana Yetano Basilio Acerete

University of Zaragoza, Spain

Th ere is widespread acceptance that current institutions are inadequate to address the challenges of sustainable development. At the same time, there is an urgent need to build awareness and increase capacity for promot-ing action with respect to environmental protection at the local level. Th is article analyzes the Web sites of the environment departments of European local governments that signed the Aalborg Commitments to determine the extent to which they are using the Internet to promote e-participation in environmental topics and to identify the drivers of these developments. Potential drivers are public administration style, urban vulnerability, external pressures, and local government environmental culture. Findings confi rm that e-participation is a multifaceted concept. External pressures infl uence the transparency of environmental Web sites, while public administration style and local government environmental culture infl u-ence their interactivity.

T

here is widespread acceptance that current institutions are inadequate to address the chal-lenges of sustainable development and that new arrangements are needed to achieve economic, environmental, and social objectives in a balanced and integrated way. While sustainable development has received international attention and become a global philosophy,1 the economic and fi nancial crisis couldbe eroding social and environmental concerns and values and creating a sustainability downturn (Cooper and Pearce 2011; Correa-Ruiz and Moneva-Abadía 2011).

Th e failure to develop a global agreement on climate protection and the global fi nancial crisis are good reasons to consider the possible benefi ts of actions on a smaller scale (Ostrom 2009). According to Sheppard et al. (2011), there is an urgent need for meaning-ful information and eff ective public processes at the local level to build awareness and increase capacity for promoting environmental protection. Household con-sumption patterns and behavior have a major impact on natural resource stocks, environmental quality, and climate change. Furthermore, projections indicate that

these impacts are likely to increase in the near future (OECD 2011).

Th e literature has emphasized the strong role of stakeholder involvement in sustainability issues (Alió and Gallego 2002; Astleithner and Hamedinger 2003; Portney 2005, 2013; Wang et al. 2012). A citizen who is well informed about environmental policies and initiatives can become part of the global eff ort for environmental protection. Th e use of information and communications technologies and, in particular, the Internet may have an important role in this regard, given the potential for informing, educating, and empowering citizens. Th us, the use of e-participation may be a cost-eff ective tool to actively involve citizens in environmental protection.

Th is article analyzes the Web sites of the environment departments of European local governments that have signed the Aalborg Commitments. Th e aim is to estab-lish to what extent these presumably committed local governments are making use of the Internet to pro-mote environmentally friendly behaviors among their citizens and to off er them opportunities for strength-ening democracy by creating e-participation tools. Particular attention will be paid to the type of citizen participation being promoted: information, consulta-tion, or active involvement (Martin and Boaz 2000; OECD 2001). Th e article also analyzes why some local governments voluntarily make a greater eff ort in e-participation regarding environmental topics than others. It seeks answers to the following research ques-tions: (1) Does the signing of nonmandatory commit-ments, such as the Aalborg Commitcommit-ments, promote the use of environmental e-participation initiatives? (2) Are these initiatives oriented toward promoting higher levels of citizen participation and involvement or just toward enhancing transparency? And (3) what factors drive the diff erences in the development of these tools at local level?

Th is study is useful for two main purposes. First, it serves as a check for public sector managers to

active in sustainable development (such as Eurocites and ICLEI) have also joined this initiative.

Th e Aalborg Commitments were adopted in 2004 as a follow-up to the Aalborg Charter. Th e commitments envisage “cities and towns that are inclusive, prosperous, creative and sustainable, and that pro-vide a good quality of life for all citizens and enable their participa-tion in all aspects of urban life.” Signatories voluntarily agree to (1) produce a review of their city within 12 months; (2) set individual environmental targets, in consultation with stakeholders, within 24 months; and (3) monitor progress in delivering the targets and regularly report to their citizens.

Th ere are 10 Aalborg Commitments, and they understand sus-tainability in a very broad sense. Th ey have a strong focus on environmental protection and highlight the importance of citizen participation,2 although they do not specify the mechanisms or tools

that should be adopted and leave much leeway to the municipal governments to decide how to put the commitments into practice. As shown by Portney (2013), sustainability is a multidimensional concept, and not all cities have the same environmental problems, but, in any case, signatories are expected to promote both citizen participation and environmental protection.

The Role of E-Participation in Environmental Protection and Determining Factors

E-Participation and Environmental Protection

Citizen engagement is considered to have positive infl uences on citizen trust in government (Cooper, Bryer, and Meek 2006; Yang 2005), governmental legitimacy (Fung 2006) and governmental responsiveness (Buček and Smith 2000; Yang and Holzer 2006). All of this positive rhetoric has led to a reemergence of ideas and values of community, localism, and citizen participation in academic and political discourse (Reddel 2002; Summerville, Adkins, and Kendall 2008). However, the literature acknowledges that authentic public participation is rarely found (Cornwall 2008; Taylor 2007, Yang and Callahan 2007) and that a big gap remains between the rhetoric on participation that is present in political discourses, legal texts, and policy documents and the real-life implementation of participatory processes (Burby 2003; Rauschmayer, Van den Hove, and Koetz 2009; Yetano, Royo, and Acerete 2010).

A precondition for the success of sustainable development and environmental protection is that these initiatives are acknowledged and attain visibility in the eyes of citizens and local

stakehold-ers (Núñez, Alessi, and Egenhofer 2010). However, local governments are often unable to foster widespread interest and engage-ment in climate-related issues (Anguelovski and Carmin 2011). E-participation can help give the necessary visibility to environmen-tal protection initiatives and promote the engagement and cooperation of citizens and other key stakeholders. In fact, the potential of the Internet to enhance civic participa-tion has been highlighted since the very beginnings of the Internet (Kakabadse, Kakabadse, and Kouzmin 2003; Mahrer and Krimmer 2005). According to the United Nations (2012, 108), e-govern-ment can play a key role in supporting sustainable develope-govern-ment evaluate and benchmark their environmental e-participation

off erings. Second, it allows legislators and environmental associa-tions to understand the motivaassocia-tions that lead to the disclosure of environmental information and the development of e-partic-ipation, as well as to consider further improvements in current environmental agreements to achieve in-depth changes within local governments.

Cities, Citizens, and Environmental Protection: The Aalborg Commitments

As a growing proportion of the global population lives in urban areas, cities are emerging as key “battlegrounds for global sustain-ability” (Núñez, Alessi, and Egehofer 2010; Krause 2012). In 2011, more than half of the world’s population lived in urban areas, and this fi gure is expected to reach 67 percent in 2050 (UNDESA 2011). Cities are central to the sustainability policy challenge because they are home to the majority of global energy use—between 60 percent and 80 percent (OECD 2010). Th us, signifi cant advances in mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and environmental protection can be achieved at local level (Anguelovski and Carmin 2011).

Participation at the urban level tends to be regarded as an essen-tial tool for climate governance (Alió and Gallego 2002; Solomon 2011), and it is an integral aspect of how some defi ne sustainabil-ity (Portney 2013; Portney and Berry 2010). For Astleithner and Hamedinger (2003), the ideal model of locally sustainable policies is characterized as a new governance mix, based on procedures such as dialogue and participation. In the case of environmental protec-tion, citizen participation is particularly important because citizens not only should be consulted on governmental actions but also can make their own contributions by changing their behavior (for example, by reducing energy consumption and private motorized transport use). In fact, one of the features that helps distinguish cities’ sustainability eff orts is the extent to which such eff orts actu-ally seek to promote citizen participation and involvement (Portney 2013).

Because local governments are the level of government closest to cit-izens, they have unique opportunities to infl uence individual behav-ior toward sustainability through education and raising awareness. Municipal governments around the world are becoming involved in environmental protection, partly in response to having realized its impact (Krause 2011). To achieve this objective, some initia-tives have been implemented in Europe and worldwide, including the Aalborg Commitments, the Covenant of

Mayors, the European Green Capital Award, and the Network of Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI).

Th e European Commission sponsored the Aalborg Commitments to provide support in implementing European strategies and poli-cies for sustainable development. At the First European Conference on Sustainable Cities and

Towns, which took place in Aalborg, Denmark, in 1994, the Charter of European Cities and Towns Towards Sustainability (known as the Aalborg Charter) was adopted as a framework for the delivery of local sustainable development. A group of 10 networks of cities and towns

E-participation can help give

the necessary visibility to

envi-ronmental protection initiatives

and promote the engagement

and cooperation of citizens and

becomes a challenge (Portney and Berry 2010), especially in studies covering diff erent countries, such as this one.

Some quantitative large-N studies focusing on the factors that infl uence cities to make explicit environmental protection commit-ments have been conducted (Brody et al. 2008; García-Sánchez and Prado-Lorenzo 2008; Krause 2011; Portney 2013; Zahran et al. 2008). Based on previous studies of environmental protection and citizen partici-pation, the following discussion develops four diff erent rationales to explain why some sig-natories of the Aalborg Commitments show higher levels of development in environmental e-participation. For each area, a proposition to be tested is indicated.

Public administration style. Some authors have pointed out (Hood 1995; Pollitt, Van Thiel, and Homburg 2007; Torres 2004) that the dissemination of public management innovations is infl uenced by the organizational and administrative culture, historical background, and legal structure. Public administration style has been an important element for explaining the evolution of other areas of public sector reforms and recent developments in e-government related to transparency, accountability, and e-participation (García-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Gallego-Álvarez 2011; Pina, Torres, and Royo 2007, 2010).

Among the countries in this study, fi ve broad styles of public admin-istration can be identifi ed: Anglo-Saxon, Eastern European, Nordic, Germanic, and Napoleonic. With regard to citizen participation, studies characterize Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Germanic countries as leaders, while Napoleonic and Eastern European countries usu-ally lag behind (Allegretti and Herzberg 2004; Royo, Yetano, and Acerete 2011; Yetano, Royo, and Acerete 2010).

Anglo-Saxon and Nordic countries have a long-standing reputa-tion of public sector reforms, transparency, and citizen engagement. Germanic countries have a long tradition of consultation with social partners (Astleithner and Hamedinger 2003; OECD 2001). On the contrary, Napoleonic and Eastern European countries are considered laggards in introducing public sector reforms, and in some of these countries, such as Spain, associations have traditionally been the only legal participants in most participative processes (Allegretti and Herzberg 2004). Th e 2012 United Nations E-Government Survey (United Nations 2012) and the Voice and Accountability Index of the World Bank show a similar pattern, with higher levels of citizen participation in Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Germanic countries. Th erefore, a priori, a higher level of development of e-participation can be expected in these cities.3

Proposition 1: Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Germanic cities

will show greater development in environmental e-participa-tion initiatives.

Urban vulnerability. Environmental protection presupposes a certain degree of pressure from environmental problems or crises (Portney 2013, Astleithner and Hamedinger 2003). It is reasonable to expect that the extent to which a locality is vulnerable to

because of its potential contribution to enhancing the effi ciency, transparency, and responsiveness of public institutions and promot-ing the participation of key stakeholders.

In spite of the recent developments in envi-ronmental protection and e-participation, the eff ectiveness of the initiatives adopted has been questioned. Krause (2011, 2012) raises legitimate questions about the extent and type of follow-through on municipal envi-ronmental protection commitments. Other authors have indicated that, in some cases, the adoption of sustainability policies represents more “greenwashing” than actual

commit-ment (Astleithner and Hamedinger 2003; Feichtinger and Pregernig 2005; Portney 2013). Furthermore, existing initiatives have been criticized for being fragmented rather than global (Romero-Lankao 2012).

Despite the current rhetoric about the benefi ts of e-participation, previous research has shown that the use of the Internet in the public sector for external purposes has been mainly directed at the provision of public services and information to citizens and other stakeholders, neglecting the citizen participation dimension (Bonsón et al. 2012; Brainard and McNutt 2010; Coursey and Norris 2008; Mahrer and Krimmer 2005; Musso, Weare, and Hale 2000; Norris and Reddick 2013; Torres, Pina, and Acerete 2006; United Nations 2012). Th e search for legitimacy also seems to be behind the adoption of e-participation initiatives (García-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Gallego-Álvarez 2011; Mahrer and Krimmer 2005).

Th erefore, local governments can be expected to vary substan-tially in their e-participation off erings. Two types of adoption of e-participation in environmental topics can be anticipated: local governments with great commitment and development and local governments that exhibit symbolic behavior, that is, those that have introduced some soft e-participation mechanisms, mainly related to the provision of information, but without a real commitment to consultation and cooperation initiatives.

Determinants of E-Participation in Environmental Issues

Th e environment is a public good that cannot readily be fenced in or allocated according to need or willingness to pay (Zahran et al. 2008). Th e nonexcludability of collective benefi ts signifi -cantly undermines incentives to participate, leading to suboptimal provision of public goods. In addition, the local authority culture (political, managerial, and organizational) of short-termism militates against a realistic view of the long haul implied by sustainability.

Local-level characteristics are the dominant drivers of cities’ deci-sions to commit to environmental protection (García-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Gallego-Álvarez 2011; Krause 2011; Portney 2013; Prado-Lorenzo and García-Sánchez 2009). Very often, the context in which citizen participation processes take place, more than the methods used, determines the ability of public sector entities to succeed. However, the identifi cation of local fac-tors that might promote sustainability is a complex task (Alió and Gallego 2002, 129), and the lack of appropriate and robust data

Th e following discussion

devel-ops four diff erent rationales to

explain why some signatories

of the Aalborg Commitments

show higher levels of

devel-opment in environmental

Web site. Th e degree of external visibility of the city is measured by the number of city visitors (tourist nights per year). Finally, it is expected that in countries where the level of development of e-environment-related policies is higher, local governments will feel more pressure to adopt environmental e-participation initiatives.6

Proposition 3: Cities with more external pressures will

show greater development in environmental e-participation initiatives.

Local government environmental culture. Betsill (2001) observed

that most of the cities belonging to environmental networks had a prior interest in environmental issues. There are many multilateral environmental agreements in effect.7 The participation of cities in

networks and competitions, namely, the Local Governments for Sustainability network, the Covenant of Mayors, and the European Green Capital Award, is considered an indicator of their willingness to implement environmental initiatives. Local Governments for Sustainability is an association of more than 1,220 local governments worldwide that are committed to sustainable development (http://www.iclei.org). Given its specifi c focus on sustainable energy and climate change, this article also takes into account whether the cities analyzed have joined the Covenant of Mayors and submitted the requested action plan for reducing their carbon emissions.8 The European Green Capital initiative is an

award that aims to provide an incentive for cities to inspire each other and share best practices while engaging in friendly competition.

Proposition 4: Cities with a higher-profi le environmental

culture will show greater development in environmental e-participation initiatives.

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

Th is article examines the signatories to the Aalborg Commitments, which, by signing, show some degree of interest in environmental protection and citizen participation. By January 2013, a total of 665 local governments had signed the Aalborg Commitments. Th ey belonged to 35 diff erent countries (some of them non-European, for example, Egypt, Israel, Morocco, Senegal, and Tunisia). Th e sample of the study was defi ned as European cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants. However, because of disproportionate representation, the number of cities studied in Italy and Spain was limited.9 Bigger

local governments were selected for this study, as they are usually the most innovative in the adoption of new technologies and, at the same time, have more need for them because the distance between the governors and the governed is greater. Th e fi nal sample com-prised 67 European cities. Th e countries covered and the number of cities per country are as follows: Austria (1), Belgium (1), Bulgaria (2), Denmark (3), Estonia (3), Finland (5), France (4), Germany (5), Greece (4), Iceland (1), Italy (8), Latvia (1), Lithuania (2), Norway (3), Portugal (3), Spain (7), Sweden (8), Switzerland (2), and the United Kingdom (4).

A comprehensive Web content analysis of the cities selected was carried out. Th e Web sites were accessed between February and April 2011, and each was analyzed for 134 items (see tables 1, 2 and

environmental problems will affect its level of commitment to promoting environmental protection (including its willingness to voluntarily introduce environmental e-participation initiatives). However, previous studies have found mixed results. Brody et al. (2008) and Zahran et al. (2008) indicated that urban vulnerability may be an explanatory factor of interest in environmental topics (defi ned as membership). However, Portney (2013), who measured the number of policies and programs adopted, found no relationship.

Th e extent of urban vulnerability to environmental problems has been measured using proxy variables such as population density, population growth rate,4 and whether the city is located on the

coast. People living in densely populated urban areas are more exposed to air pollutants, and the limits of air quality fi xed by the European Commission are often exceeded (Urban Ecosystem Europe 2007). Similarly, urban growth and development pat-terns are contributing to increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, the expected impacts of climate change are particularly harmful to coastal settlements because of the increasing risk of sea-level rise (Brody et al. 2008; Zahran et al. 2008).

Proposition 2: Cities that are more vulnerable to

mental problems will show greater development in environ-mental e-participation initiatives.

External pressures. There is increasing pressure on public sector

organizations to lead the way with sustainability practices. Environment-related behaviors, in both the public and private sectors, are often used as a public relations tool to enhance the public image of organizations (Anguelovski and Carmin 2011; Correa-Ruiz and Moneva-Abadía 2011; Solomon 2011). Recent research has shown that the online disclosure of information about policies on air pollution at the local level responds to external group demands (Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch 2012) and that the pressure exerted by interest groups is a key factor in the development of e-participation (García-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Gallego-Álvarez 2011).

Th is study considers that external pressures to adopt e-participation in environmental topics come from diff erent actors, namely, local residents, city visitors, and the central government. Th e pressure exerted by citizens is measured using the percentage of citizens with tertiary education and the share of Internet access in the region where the city is located.5 Several studies have shown that highly

educated citizens increase their involvement in pro-environment campaigns (Brody et al. 2008; Zahran et al. 2008) and that residents of cities that are more serious about sustainability are more likely to have higher educational levels (Portney and Berry 2010). According to García-Sánchez , Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Gallego-Álvarez (2011), a higher level of development of e-participation is strongly linked to countries with high technological development. Internet penetration creates demand for the information and services off ered by local government Web sites. Th us, as the level of Internet pen-etration increases, local governments will feel more social pressure to provide environmental information, online services, and e-participa-tion initiatives.

Table 1 Transparency Dimension: Average City Scores (percent)

1. Transparency-Accountability (71 items) 71.2

1.1. General information about the department (6)

Address and telephone, organization chart, number of employees, budget, annual sustainability report, mission statement 67.3

1.2. Citizen consequences (4)

Information about environmental procedures, instructions about environmental procedures, searchable index for downloadable forms or forms to submit online, instructions for appealing decision-making processes or address of an ombudsman

82.8

1.3. General information about environmental issues (14)

Strategic plan for a sustainable city, information about causes and probable impacts of climate change, index for reports and publications, drafts of new regula-tions regarding sustainability, environmental publicaregula-tions in electronic format for free, participation in national or European environmental networks/projects, Agenda 21 project and information, Agenda 21 schools program and information, information about activities linked to Agenda 21, policies for sustainable local public service delivery, local government sustainable procurement policy, FAQ (environmental topics), environmental glossary, and “What’s new” section about environmental matters

74.5

1.4. Information about specifi c policies and initiatives (41)

Carbon dioxide/energy (5), water (5), waste management/recycling (6), air quality (5), transport and mobility (11), parks and green spaces (5), noise pollution (4) 74.3

1.5. Indicators and data about sustainability (3)

Sustainability indicators defi ned, objectives and time frame established regarding these indicators, sustainability indicators reported 32.3

1.6. Information about citizen participation processes in environmental issues (3)

Information about current participatory processes (online/offl ine), information about the level of participation and results of past participatory processes (online/ offl ine), information about future participatory processes

43.8

Note: Numbers in parentheses represent the number of items in each dimension.

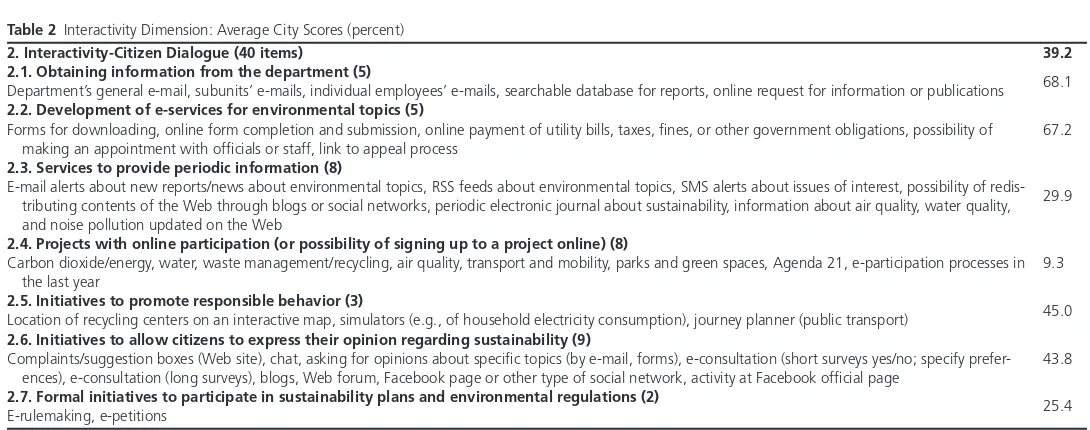

Table 2 Interactivity Dimension: Average City Scores (percent)

2. Interactivity-Citizen Dialogue (40 items) 39.2

2.1. Obtaining information from the department (5)

Department’s general e-mail, subunits’ e-mails, individual employees’ e-mails, searchable database for reports, online request for information or publications 68.1

2.2. Development of e-services for environmental topics (5)

Forms for downloading, online form completion and submission, online payment of utility bills, taxes, fi nes, or other government obligations, possibility of making an appointment with offi cials or staff, link to appeal process

67.2

2.3. Services to provide periodic information (8)

E-mail alerts about new reports/news about environmental topics, RSS feeds about environmental topics, SMS alerts about issues of interest, possibility of redis-tributing contents of the Web through blogs or social networks, periodic electronic journal about sustainability, information about air quality, water quality, and noise pollution updated on the Web

29.9

2.4. Projects with online participation (or possibility of signing up to a project online) (8)

Carbon dioxide/energy, water, waste management/recycling, air quality, transport and mobility, parks and green spaces, Agenda 21, e-participation processes in the last year

9.3

2.5. Initiatives to promote responsible behavior (3)

Location of recycling centers on an interactive map, simulators (e.g., of household electricity consumption), journey planner (public transport) 45.0

2.6. Initiatives to allow citizens to express their opinion regarding sustainability (9)

Complaints/suggestion boxes (Web site), chat, asking for opinions about specifi c topics (by e-mail, forms), e-consultation (short surveys yes/no; specify prefer-ences), e-consultation (long surveys), blogs, Web forum, Facebook page or other type of social network, activity at Facebook offi cial page

43.8

2.7. Formal initiatives to participate in sustainability plans and environmental regulations (2)

E-rulemaking, e-petitions 25.4

Note: Numbers in parentheses represent the number of items in each dimension.

3).10 As the study aims to analyze the use of the Internet to promote

environmental protection and e-participation, the items included refer to e-participation in its broader sense, including the online disclosure of information and some e-services (permits, licenses, and grants) related to environmental topics. Most items are rated 1 if they appeared on the Web site and 0 if not. Some items are scored 0.5 if they partially fulfi lled the coding criteria. Th is method has been used previously in the analysis of local government Web sites (Pina, Torres, and Royo 2007, 2010; Torres, Pina, and Acerete 2006).

Dimensions Analyzed

Th e level of development of e-participation regarding environmental issues was assessed by grouping the 134 items into four dimen-sions: transparency, interactivity, usability, and Web site maturity, which are adapted from Pina, Torres, and Royo (2007). Most of the items analyzed belong to transparency and interactivity, the two key dimensions of the study. Citizen participation eff orts can take many forms that can be classifi ed into three main types (Martin and Boaz 2000; OECD 2001): information, consultation, and active partici-pation (also known as cooperation). Th e transparency dimension is

related to the fi rst type (information). As a clear distinction between consultation and active participation is diffi cult to draw in practice (OECD 2001), the interactivity dimension includes items related to these two types of citizen participation. Th e other two complemen-tary dimensions analyze the usability and accessibility of Web sites and aspects related to Web site sophistication. Th ese are key aspects to ensure that citizens can easily access the information and facilities provided (usability) and indicate standards of Web site quality (Web site maturity).

usability, and Web site maturity and weighting each of the fi rst two dimensions by 40 percent and each of the last two dimensions by 10 percent to refl ect their relative importance to e-participation. As indicated earlier, the fi rst two dimensions are the most important in this research because they measure the development of e-partici-pation on environmental topics. Th e other two are complementary dimensions that represent the capacity of the local government Web site to support e-participation developments. Th e analysis of the development of e-participation requires the study of these four dimensions, but with a greater weight in transparency and inter-activity. Pina, Torres, and Royo (2007, 2009) previously used this weighting method. According to O’Sullivan, Rassel, and Berner (2007), index defi nitions should be consistent with past research unless a rationale exists for doing otherwise.

Statistical Techniques

Th e research fi rst carried out descriptive analysis to provide a general perspective on the use that European local governments that are signatories to the Aalborg Commitments make of the Internet in environment-related activities. Th en, univariate and multivari-ate analyses analyzed which factors cause divergences in the level of development of e-participation. Besides the variables used to measure public administration style, urban vulnerability, external pressures, and local government environmental culture, the popula-tion of each city was also included as a control variable.

Pearson correlations tested the infl uence of the continuous inde-pendent variables, while the Mann-Whitney U test assessed the infl uence of dichotomous independent variables. Th e independent variables for which a signifi cant relationship was found with the e-participation indices were then included in the regression analysis (using the ordinary least squares estimation11). Th is multivariate

analysis enabled us to study more deeply the determinants that infl uence the decision of the local governments analyzed to volun-tarily implement environmental e-participation initiatives. Interactivity (40 items) is a measure of the degree of immediate

feedback and the development of possibilities to interact with the environment department, either through online services or through citizen dialogue and e-participation initiatives. Th e items analyzed are classifi ed into seven categories related to (1) the possibilities of obtaining information from the department, (2) the development of e-services, (3) services to be updated with periodic information, (4) projects with online participation (or the possibility of signing up for a project online), (5) initiatives to promote environmentally friendly behaviors, (6) initiatives to allow citizens to express their opinion regarding sustainability processes (complaint/suggestion boxes, chats, e-consultations, blogs, online forums, social media), and (7) more formal online initiatives to participate in sustainable planning and local environmental regulations by sending comments or promoting discussion on drafts about environmental regulations (e-rulemaking) or by using an e-petitions system.

Usability (9 items) refers to the ease with which users can access information and navigate the Web portal. Th is dimension has been included because Web portals deliver value to users according to how accessible and usable the specifi c contents are. Th e features included in this section refer to general characteristics of the local entity Web site and online facilities for people with some kind of disability. Finally, Web site maturity (14 items) embraces those aspects that indicate a high degree of Web site sophistication, such as regular updating of the Web site, the existence of an interactive database of environmental indicators, the possibility of downloading them in Microsoft Excel format, audio/video fi les for environment-related activities, and the possibility of commenting on them.

Th e partial scores in transparency, interactivity, usability, and Web site maturity were obtained by adding the individual scores for each item in each dimension and dividing the total by the maximum pos-sible score in each dimension. Th e total scores of Web sites by city were obtained by adding the scores for transparency, interactivity,

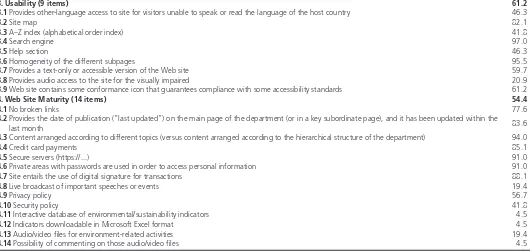

Table 3 Usability and Web Site Maturity Dimensions: Average City Scores (percent)

3. Usability (9 items) 61.2

3.1 Provides other-language access to site for visitors unable to speak or read the language of the host country 46.3

3.2 Site map 82.1

3.3 A–Z index (alphabetical order index) 41.8

3.4 Search engine 97.0

3.5 Help section 46.3

3.6 Homogeneity of the different subpages 95.5

3.7 Provides a text-only or accessible version of the Web site 59.7

3.8 Provides audio access to the site for the visually impaired 20.9

3.9 Web site contains some conformance icon that guarantees compliance with some accessibility standards 61.2

4. Web Site Maturity (14 items) 54.4

4.1 No broken links 77.6

4.2 Provides the date of publication (“last updated”) on the main page of the department (or in a key subordinate page), and it has been updated within the

last month 83.6

4.3 Content arranged according to different topics (versus content arranged according to the hierarchical structure of the department) 94.0

4.4 Credit card payments 85.1

4.5 Secure servers (https://...) 91.0

4.6 Private areas with passwords are used in order to access personal information 91.0

4.7 Site entails the use of digital signature for transactions 88.1

4.8 Live broadcast of important speeches or events 19.4

4.9 Privacy policy 56.7

4.10 Security policy 41.8

4.11 Interactive database of environmental/sustainability indicators 4.5

4.12 Indicators downloadable in Microsoft Excel format 4.5

4.13 Audio/video fi les for environment-related activities 19.4

“initiatives to promote responsible behavior” and “initiatives to allow citizens to express their opinion regarding sustainability” obtain intermediate scores of around 45 percent. Again, important variations in the categories exist, with a sharp decrease in those that imply opening the debate to the citizens (e-rulemaking and e-petitions) and the existence of projects with online participation.

Similar results can be found in the usability and Web site maturity dimensions (table 3). Usability shows a high degree of development in technical items (search engine, homogeneity of subpages, and site map) but low percentages of development in items that enhance the accessibility of Web sites and bring about social inclusion, such as text-only versions, audio access for the visually impaired, diff erent languages, or compliance with international accessibility standards. Likewise, in the Web site maturity dimension, the technical items (no broken links, last update) and those related to service delivery (credit card payments, secure servers for transactions, private areas, digital signature) are the most developed, whereas the items related to innovation and citizen participation, such as live broadcasts of important speeches or events, interactive database of environmen-tal indicators, indicators downloadable in Microsoft Excel format, audio/video fi les for environment-related activities, and the possibil-ity of commenting on them, show the lowest scores.

Th e average total score of the sample is 55.7 percent (see table 4), showing a moderate degree of development of e-participation among the biggest European cities that have signed the Aalborg

Analysis of Results

Tables 1–3 show the average score of each dimension and the aver-age frequency of implementation of each category of items or indi-vidual items. In the transparency dimension (table 1), the category related to service delivery, “citizen consequences,” is the most highly developed. High scores are also obtained for “general information about environmental issues” and “information about specifi c poli-cies and initiatives.” Conversely, the items included in “indicators and data about sustainability” and “information about citizen par-ticipation processes in environmental issues,” which allow citizens to access updated data about the state of the environment and infor-mation about past and future participatory processes, present levels of implementation below 45 percent. Th us, the disclosure levels are lower when the information requires a greater eff ort of elaboration or when it is related to participatory processes.

In regard to the interactivity dimension (table 2), an important drop in the global mean can be seen (39.2 percent versus 71.2 percent for transparency). Th e categories related to the possibility of obtaining information from the environment department and the development of e-services are the most highly developed, with average scores of 68.1 percent and 67.2 percent, respectively. Th e least developed groups of items are those related to the existence of projects with online participation (9.3 percent), formal initiatives to participate in sustainability plans and environmental regulations (25.4 percent), and the possibility of receiving periodic informa-tion about environmental topics (29.9 percent). Th e categories

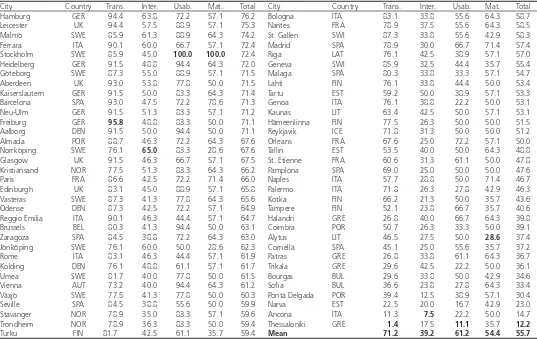

Table 4 Ranking of Cities and Scores of E-Participation Dimensions (percent)

City Country Trans. Inter. Usab. Mat. Total City Country Trans. Inter. Usab. Mat. Total

Hamburg GER 94.4 63.8 72.2 57.1 76.2 Bologna ITA 83.1 33.8 55.6 64.3 58.7

Leicester UK 94.4 57.5 88.9 57.1 75.3 Nantes FRA 78.9 37.5 55.6 64.3 58.5

Malmö SWE 85.9 61.3 88.9 64.3 74.2 St. Gallen SWI 87.3 33.8 55.6 42.9 58.3

Ferrara ITA 90.1 60.0 66.7 57.1 72.4 Madrid SPA 78.9 30.0 66.7 71.4 57.4

Stockholm SWE 85.9 45.0 100.0 100.0 72.4 Riga LAT 76.1 42.5 38.9 57.1 57.0

Heidelberg GER 91.5 48.8 94.4 64.3 72.0 Geneva SWI 85.9 32.5 44.4 35.7 55.4

Göteborg SWE 87.3 55.0 88.9 57.1 71.5 Malaga SPA 80.3 33.8 33.3 57.1 54.7

Aberdeen UK 93.0 53.8 77.8 50.0 71.5 Lahti FIN 76.1 33.8 44.4 50.0 53.4

Kaiserslautern GER 91.5 50.0 83.3 64.3 71.4 Tartu EST 59.2 50.0 38.9 57.1 53.3

Barcelona SPA 93.0 47.5 72.2 78.6 71.3 Genoa ITA 76.1 38.8 22.2 50.0 53.1

Neu-Ulm GER 91.5 51.3 83.3 57.1 71.2 Kaunas LIT 63.4 42.5 50.0 57.1 53.1

Freiburg GER 95.8 48.8 83.3 50.0 71.1 Hämeenlinna FIN 77.5 26.3 50.0 50.0 51.5

Aalborg DEN 91.5 50.0 94.4 50.0 71.1 Reykjavik ICE 71.8 31.3 50.0 50.0 51.2

Almada POR 88.7 46.3 72.2 64.3 67.6 Orleans FRA 67.6 25.0 72.2 57.1 50.0

Norrköping SWE 76.1 65.0 83.3 28.6 67.6 Tallin EST 53.5 40.0 50.0 64.3 48.8

Glasgow UK 91.5 46.3 66.7 57.1 67.5 St. Etienne FRA 60.6 31.3 61.1 50.0 47.8

Kristiansand NOR 77.5 51.3 83.3 64.3 66.2 Pamplona SPA 69.0 25.0 50.0 50.0 47.6

Paris FRA 86.6 42.5 72.2 71.4 66.0 Naples ITA 57.7 28.8 50.0 71.4 46.7

Edinburgh UK 83.1 45.0 88.9 57.1 65.8 Palermo ITA 71.8 26.3 27.8 42.9 46.3

Vasteras SWE 87.3 41.3 77.8 64.3 65.6 Kotka FIN 66.2 21.3 50.0 35.7 43.6

Odense DEN 87.3 42.5 72.2 57.1 64.9 Tampere FIN 52.1 23.8 66.7 35.7 40.6

Reggio Emilia ITA 90.1 46.3 44.4 57.1 64.7 Halandri GRE 26.8 40.0 66.7 64.3 39.8

Brussels BEL 80.3 41.3 94.4 50.0 63.1 Coimbra POR 50.7 26.3 33.3 50.0 39.1

Zaragoza SPA 84.5 38.8 72.2 64.3 63.0 Alytus LIT 46.5 27.5 50.0 28.6 37.4

Jönköping SWE 76.1 60.0 50.0 28.6 62.3 Cornellá SPA 45.1 25.0 55.6 35.7 37.2

Rome ITA 83.1 46.3 44.4 57.1 61.9 Patras GRE 26.8 33.8 61.1 64.3 36.7

Kolding DEN 76.1 48.8 61.1 57.1 61.7 Trikala GRE 29.6 42.5 22.2 50.0 36.1

Umea SWE 81.7 40.0 77.8 50.0 61.5 Bourgas BUL 29.6 33.8 50.0 42.9 34.6

Vienna AUT 73.2 40.0 94.4 64.3 61.2 Sofi a BUL 36.6 23.8 27.8 64.3 33.4

Växjö SWE 77.5 41.3 77.8 50.0 60.3 Ponta Delgada POR 39.4 12.5 38.9 57.1 30.4

Seville SPA 84.5 38.8 55.6 50.0 59.9 Narva EST 22.5 20.0 16.7 42.9 23.0

Stavanger NOR 78.9 35.0 83.3 57.1 59.6 Ancona ITA 11.3 7.5 22.2 50.0 14.7

Trondheim NOR 78.9 36.3 83.3 50.0 59.4 Thessaloniki GRE 1.4 17.5 11.1 35.7 12.2

Turku FIN 81.7 42.5 61.1 35.7 59.4 Mean 71.2 39.2 61.2 54.4 55.7

dimensions, although higher in transparency and usability. Th ese results show that the signing of the Aalborg Commitments has not

promoted convergence in the level of use of e-participation in environmental issues at the local level in Europe. Th e results also suggest that in order to improve their e-participation off erings, most cities are promoting the devel-opment of transparency and usability (the dimensions that require less eff ort and cost), creating great diff erences in the development of these two dimensions in comparison with interactivity and maturity.

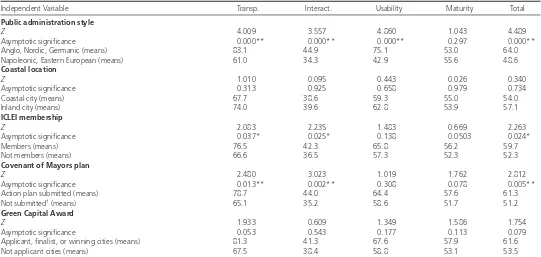

Tables 5 and 6 include the results of the univariate analyses. Table 5 shows a positive correlation between the total e-participation index and the population growth rate, tourist nights per year, the level of Internet access, and the level of development of e-environment policies at the central level. While transparency shows a similar behavior, interactivity is not related to tourist nights per year. Usability is related to the same variables, except for tourist nights, and with the addition of tertiary education. Web site maturity only shows a relationship with three variables: population growth, tourist nights, and population. Th e results of the Mann-Whitney tests show that public administration style, ICLEI membership, and having a Covenant of Mayors plan all have a positive and signifi cant correlation with the total, transpar-ency, and interactivity e-participation indices (see table 6). None of the dichotomous independent variables, except public administration style, is related to usability, and none of them with Web site maturity.

Th ese results show that some, but not all, variables from the four areas—public administration style, urban vulnerability, external Commitments. Th e transparency of local governments about

inter-nal works and decision processes dealing with procedures to reach environmental commitments is the dimension

that scores the highest average value (71.2 percent). On the contrary, the possibility of citizens interacting online with the corre-sponding local government department is the dimension with the lowest score, only 39.2 percent. Th e other two dimensions, usability and sophistication of the Web site, have values quite close to the average e-participation score.

Looking at the data from the individual cit-ies (table 4), most local governments obtain transparency scores of more than 75 percent (44 local governments). On the contrary, the maximum score obtained in interactivity is 65 percent, and only 12 local governments

obtain scores over 50 percent in this dimension. Th e diff er-ences between the minimum and maximum are great in the four

Table 5 Pearson Correlations (continuous independent variables)

Transp. Interact. Usability Maturity Total Population density –0.136 –0.133 –0.099 0.101 –0.134 Population growth rate

(% 2001–11)

0.324** 0.296** 0.362** 0.311* 0.377**

% Tertiary education 0.116 0.115 0.279* 0.052 0.155 % Internet access in the

region

0.568** 0.373** 0.621** 0.000 0.564**

Tourist nights per year (log) (N = 48)

0.373** 0.203 0.264 0.424** 0.373**

National e-environment 0.485** 0.306* 0.550** 0.020 0.482** Population (log) 0.203 0.126 0.035 0.434** 0.208

** Signifi cant at the 1% level; * signifi cant at the 5% level.

Table 6 Mann-Whitney Tests (dichotomous independent variables)

Independent Variable Transp. Interact. Usability Maturity Total

Public administration style Anglo, Nordic, Germanic (means)

Napoleonic, Eastern European (means)

Not submitted† (means)

78.7 Applicant, fi nalist, or winning cities (means)

Not applicant cities (means)

**Signifi cant at the 1% level; *signifi cant at the 5% level.

†Not submitted or not adhering to the Covenant of Mayors initiative.

Th ese results show that some,

but not all, variables from the

four areas—public

administra-tion style, urban vulnerability,

external pressures, and local

government environmental

culture—are related to

devel-opments in e-participation,

especially to the key dimensions

of this study: the total,

Discussion

Th is article analyzed the level of development of environmental e-participation initiatives in European local governments that were signatories to the Aalborg Commitments. Results show that, in gen-eral terms, the use of environmental e-participation initiatives is still in its infancy in these presumably committed cities. Membership in some environmental networks frequently results in symbolic adop-tion because of the minimal costs associated with membership and the lack of follow-through actions, which makes it easy for weakly committed cities to join (Krause 2012).

Th e total e-participation average (55.7 percent) indicates a low level of development among cities that are interested in environmental topics and citizen participation. Furthermore, results show impor-tant variations among signatory cities. Th is suggests that becoming a signatory to the Aalborg Commitments has not fostered conver-gence in the development of e-participation in environment-related topics and that other variables need to be studied to understand the developments in this area. Similar results were obtained by Krause (2011) and Wang et al. (2012) when analyzing membership in climate protection networks in the United States. It could be argued that signing the Aalborg Commitments, in some cases, is just a symbolic act to present an image of modernity, global citizenship, and commitment to the environment and citizen participation but without promoting signifi cant changes in government-to-citizen relationships.

A further objective was to see whether e-participation in envi-ronmental issues was being used only to inform citizens about policies and practices (transparency) or also to promote debate and active participation (interactivity). The results show that, similar to other citizen participation studies (Yetano, Royo, and Acerete 2010), the developments in e-participation are higher in transparency. However, it is noticeable that when this information requires a greater effort from the local government, the level of disclosure decreases. The level of development of interactivity and citizen dialogue is much smaller. The offer of

real participative projects, up-to-date indicators, or e-petition initiatives is hardly present. These findings are consistent with previous research (Bonsón et al. 2012; Coursey and Norris 2008; Norris and Reddick 2013), indicating that local e-gov-ernment is mainly informational, with some transactions but virtually no indication of the high-level functions predicted at the theoretical level.

pressures, and local government environmental culture—are related to developments in e-participation, especially to the key dimen-sions of this study: the total, transparency, and interactivity scores. In order to show whether these factors are driving the development of local governments in environmental e-participation initiatives, regression analysis has been applied.

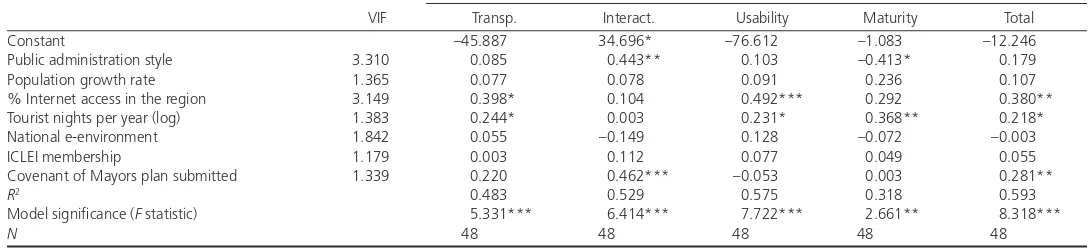

Five regression analyses were run, one per e-participation score, tak-ing the scores in table 4 as dependent variables. As table 7 shows, all of the models are statistically signifi cant, the signs of the signifi cant coeffi cients are in the expected direction, and high R2 coeffi cients are

obtained (ranging from 0.32 to 0.59).12 Th e variables that explain

the total environmental e-participation index of the cities are tour-ist nights, the level of Internet access in the region, and having a Covenant of Mayors plan. Th erefore, the implementation of e-partic-ipation in environmental issues is driven by a combination of external pressures and local government environmental culture. However, important insights are obtained by analyzing the infl uence of the independent variables on transparency and interactivity separately.

External pressures, in particular the Internet access and tourist nights variables, infl uence the transparency of local government environmen-tal Web sites. Cities seem to be interested in creating a good image for visitors who may use the municipal Web site to look for information about the city they plan to visit. Similar reasoning can be used to explain the infl uence of the level of Internet access in the region, as it refl ects potential visits to the Web site by local residents. Local govern-ment environgovern-mental culture (represented by having a Covenant of Mayors plan) and public administration style infl uence the interactiv-ity of the environmental section of the local government Web site, confi rming what other studies about the use of new technologies have concluded in diff erent areas of public management.

To summarize, these empirical results provide support for propo-sitions 1 (public administration style explains the level of inter-activity of environmental Web sites) and 4 (local government environmental culture, measured by the Covenant of Mayors plan, explains both the level of interactivity and the total score). In regard to proposition 3 (external pressures), it has been found to explain a higher disclosure of environmental information (informa-tion-transparency side of citizen participation) but not the consul-tation-active participation side of citizen participation. Finally, no empirical evidence supporting proposition 2 (urban vulnerability) has been found.

Table 7 Standardized Regression Coeffi cients and Statistical Signifi cance

Dependent Variable

VIF Transp. Interact. Usability Maturity Total

Constant –45.887 34.696* –76.612 –1.083 –12.246

Public administration style 3.310 0.085 0.443** 0.103 –0.413* 0.179

Population growth rate 1.365 0.077 0.078 0.091 0.236 0.107

% Internet access in the region 3.149 0.398* 0.104 0.492*** 0.292 0.380**

Tourist nights per year (log) 1.383 0.244* 0.003 0.231* 0.368** 0.218*

National e-environment 1.842 0.055 –0.149 0.128 –0.072 –0.003

ICLEI membership 1.179 0.003 0.112 0.077 0.049 0.055

Covenant of Mayors plan submitted 1.339 0.220 0.462*** –0.053 0.003 0.281**

R2 0.483 0.529 0.575 0.318 0.593

Model signifi cance (F statistic) 5.331*** 6.414*** 7.722*** 2.661** 8.318***

N 48 48 48 48 48

Th e creation of a true e-dialogue seems to remain a pending issue for European local governments, even in local governments that are presumably committed to promoting citizen participation in environmental topics. As Romero-Lankao (2012) argues, given the complexity of the interconnected processes involved in the relationships between cities and the environment, it is not surprising that local authorities tend to move toward rhetoric rather than meaningful responses. As a con-sequence, it does not seem that the Internet

is going to lead to a revolution in government-to-citizen relation-ships or to a convergence in governance styles and decision-making structures (at least in the short term). Th us, the theoretical claims that indicate that the Internet is going to foster a revitalization of the public sphere must be taken with caution.

Th e article also aimed to identify the factors that foster the develop-ment of e-participation in environdevelop-mental topics. Th ese factors are classifi ed into four areas: public administration style, urban vulner-ability, external pressures, and local government environmental culture. Overall, the fi ndings confi rm that e-participation is a mul-tifaceted concept, with diff erent perspectives whose development is driven by diff erent rationales. Empirical results show that although some correlation exists between public administration style and the development of the e-participation indices, this variable is only explanatory for interactivity in the regression

analysis. Th is suggests that the steps toward

real e-participation are only taken by local governments that have a public administra-tion style that is more friendly toward citizen participation, which confi rms the fi ndings of García-Sánchez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Gallego-Álvarez (2011).

In regard to urban vulnerability, our results show that it does not explain developments in e-participation related to environmental protection, which is consistent with Portney (2013). External pressures have a greater infl uence on the disclosure of environmental information (information-transparency side of citizen participation) than on the

consul-tation-active participation side. Th ese external pressures seem to be favoring a narrow approach to the implementation of environ-mental e-participation initiatives, centered more on the diff usion of information than on really promoting the active participation of citizens in environmental policies and processes.

With regard to local government environmental culture, only local governments with an active commitment (having submitted the Covenant of Mayors plan) show greater developments in interactiv-ity and higher total e-participation scores. Overall, these results are an example of “politics as usual” in the adoption of new technolo-gies, as local governments that are traditionally more concerned about citizen participation and environmental issues are those that make more use of new technologies to promote environmentally friendly behaviors among citizens and off er more possibilities

for e-participation. Th us, e-government is confi rmed as mainly an add-on to traditional government-to-citizen relationships (Coursey and Norris 2008).

Finally, the limitations of this study should be acknowledged and the avenues for further research indicated. As in all Web content analyses, this study is just a snapshot of local government practices at a specifi c moment in time, and future research should update the fi ndings obtained here. Future studies could compare cities that are members of environmental associations with nonmembers to clarify the eff ects of membership. Perhaps the main extension for future research should be a greater emphasis on the real impact of environmental e-participation projects, reinforcing the qualitative analysis of the specifi c online initiatives of the local entities and the changes in governmental actions resulting from the use of e-participation tools.

Conclusions

Local governments have adopted a narrow approach to the imple-mentation of environmental e-participation initiatives, using their Web sites mainly as a public relations tool. As a consequence, they are missing out on opportunities to make use of the Internet to promote e-participation and citizen engagement in environmental protection. All of this shows that previous studies focusing only on

membership in environmental associations may have overlooked the real commitments resulting from these memberships. As mem-bership does not equal action, it is necessary to evaluate local government developments so as to identify best practices and determine local governments’ levels of commitment.

Legislators and environmental associations need to take additional steps to foster action. Initially, membership seemed to be enough to promote environmental awareness and has been fruitful in diff using the importance of environmental protection. But now, further initiatives, which may include incentives, more specifi c guidelines or requirements, and follow-through actions, are needed. Future research should try to shed light on which measures are more eff ec-tive to achieve in-depth changes within local governments.

Acknowledgments

Th is study was carried out with the fi nancial support of the Spanish National Research and Development Plan through research project EC02010-17463 (ECON-FEDER) and of the European Science Foundation/European Collaborative Research Projects through project EUI2008-03788.

Notes

1. Earth Summit in Rio (1992), Kyoto Protocol (1997), Copenhagen Climate Change Conference (2009), and Rio+20 Conference (2012).

2. Th e fi rst commitment (governance) deals with participatory democracy, while other commitments deal with environmental protection, including the second

Local governments have

adopted a narrow approach to

the implementation of

envi-ronmental e-participation

initiatives, using their Web sites

mainly as a public relations

tool. As a consequence, they are

missing out on opportunities to

make use of the Internet to

pro-mote e-participation and citizen

engagement in environmental

protection.

Th e creation of a true e-dialogue

seems to remain a pending

issue for European local

ernments, even in local

gov-ernments that are presumably

committed to promoting citizen

(local management toward sustainability), fourth (responsible consumption and lifestyle choices), and sixth (better mobility, less traffi c). A full description of the Aalborg Commitments can be found at http://www.sustainablecities.eu. 3. To test this proposition, a dummy variable is defi ned the takes the value of 1 for

Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Germanic cities and 0 otherwise.

4. Th is variable is measured as the percentage of variation of the city’s popula-tion during a 10-year period (2001–2011). Data obtained from http://www. citypopulation.de.

5. It is not possible to obtain data on Internet access at the city level. Internet access at the regional level is taken from the Eurostat database.

6. To measure the level of pressure from the central government, the e-environ-ment scores of the United Nations E-Governe-environ-ment Survey have been used (2012, 135).

7. By 2005, the United Nations Environmental Programme listed more than 200 (UNEP 2005).

8. Th e Covenant of Mayors is a European Commission initiative launched in January 2008 that asks mayors to compromise to cut carbon emissions by at least 20 percent by 2020 (http://www.eumayors.eu/).

9. In Italy and Spain, the inclusion of all of the signatory cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants would have distorted the composition of the sample. According to García-Sánchez and Prado-Lorenzo (2008), the number of municipalities that have signed on in Italy and Spain is too high to be assumed realistically. Th e public management literature (Hood 1995; Pollitt, Van Th iel, and Homburg 2007; Torres 2004) often distinguishes Southern European coun-tries for adopting symbolic policies. In these two councoun-tries, only the fi ve most populated cities have been included, together with some other cities with a good reputation regarding sustainability and environmental policies.

10. Most of the items have been derived from the lists of the Aalborg Commitments and the European Commission framework Cohesion Policy and Cities (European Commission 2006) and refer specifi cally to the environment. Other relevant items usually included in local governments’ Web site content analyses have also been included. Because of space requirements, tables 1 and 2 only include a summary of the items analyzed. Th e complete tables with data on individual items are available from the authors upon request.

11. Th e results of the regression analysis are almost the same if all possible ent variables are included in the model. However, the exclusion of the independ-ent variables with no signifi cant relationship found in the univariate analysis is preferred because of higher VIF coeffi cients that could suggest the existence of multicollinearity problems when including all the variables.

12. As can be seen in table 7, only 48 cities have been included in the regression analysis. Th e reason is that the variable for tourist nights per year has missing data for 19 cities.

References

Al ió, M. Àngels, and Albert Gallego. 2002. Civic Entities in Environmental Local Planning: A Contribution from a Participative Research in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona. GeoJournal 56(2): 123–34.

Alle gretti, Giovanni, and Carsten Herzberg. 2004. Participatory Budgets in Europe: Between Effi ciency and Growing Local Democracy. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute. http://www.tni.org/sites/www.tni.org/archives/reports/newpol/partici-patory.pdf [accessed November 7, 2013].

Angu elovski, Isabelle, and JoAnn Carmin. 2011. Something Borrowed, Everything New: Innovation and Institutionalization in Urban Climate Governance.

Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 3(3): 169–75.

Astl eithner, Florentina, and Alexander Hamedinger. 2003. Urban Sustainability as a New Form of Governance: Obstacles and Potentials in the Case of Vienna.

Innovation: Th e European Journal of Social Sciences 16(1): 51–75.

Bets ill, Michele M. 2001. Mitigating Climate Change in U.S. Cities: Opportunities and Obstacles. Local Environment 6(4): 393–406.

Bons ón, Enrique, Lourdes Torres, Sonia Royo, and Francisco Flores. 2012. Local E-Government 2.0: Social Media and Corporate Transparency in Municipalities.

Government Information Quarterly 29(2): 123–32.

Brain ard, Lori A., and John G. McNutt. 2010. Virtual Government–Citizen Relations: Informational, Transactional, or Collaborative? Administration & Society 42(7): 836–58.

Brody , Samuel D., Sammy Zahran, Himanshu Grover, and Arnold Vedlitz. 2008. A Spatial Analysis of Local Climate Change Policy in the United States: Risk, Stress, and Opportunity. Landscape and Urban Planning 87(1): 33–41.

Buček , Ján, and Brian Smith. 2000. New Approaches to Local Democracy: Direct Democracy, Participation and the “Th ird Sector.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 18(1): 3–17.

Burby, R aymond, J. 2003. Making Plans that Matter: Citizen Involvement and Government Action. Journal of the American Planning Association 69(1): 33–49. Cooper, Stuart, and Graham Pearce. 2011. Climate Change Performance

Measurement, Control and Accountability in English Local Authority Areas.

Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 24(8): 1097–1118. Cooper, Terry L., Th omas A. Bryer, and Jack W. Meek. 2006. Citizen-Centered

Collaborative Public Management. Special issue, Public Administration Review

66: 76–88.

Cornwall , Andrea. 2008. Democratising Engagement: What the UK Can Learn from International Experience. London: Demos.

Correa-R uiz, Carmen, and José Mariano Moneva-Abadía. 2011. Special Issue on “Social Responsibility Accounting and Reporting in Times of Sustainability Downturn/Crisis.” Supplement, Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review 14: 187–211.

Coursey, Da vid, and Donald F. Norris. 2008. Models of E-Government: Are Th ey Correct? An Empirical Assessment. Public Administration Review 68(3): 523–36.

European Co mmission. 2006. Cohesion Policy and Cities: Th e Urban Contribution to Grow and Jobs in the Regions. http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/regional_ policy/review_and_future/g24239_en.htm [accessed November 7, 2013]. Feichtinger , Judith, and Michael Pregernig. 2005. Participation and/or/versus

Sustainability? Tensions between Procedural and Substantive Goals in Two Local Agenda 21 Processes in Sweden and Austria. European Environment 15(4): 212–27.

Fung, Archon. 2006. Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance. Special issue, Public Administration Review 66: 66–75.

García-Sánche z, Isabel M., and Jose-Manuel Prado-Lorenzo. 2008. Determinant Factors in the Degree of Implementation of Local Agenda 21 in the European Union. Sustainable Development 16(1): 17–34.

García-Sánchez, Isabel-María, Luis Rodríguez-Domínguez, and Isabel Gallego-Álvarez. 2011. Th e Relationship between Political Factors and the Development of E-Participatory Government. Information Society 27(4): 233–51.

Grimmelikhuijsen, Ste phan G., and Eric W. Welch. 2012. Developing and Testing a Th eoretical Framework for Computer-Mediated Transparency of Local Governments. Public Administration Review 72(4): 562–71.

Hood, Christopher. 19 95. Th e New Public Management in the 1980s—Variations on a Th eme. Accounting Organizations and Society 20(2–3): 93–109. Kakabadse, Andrew, Na da K. Kakabadse, and Alexander Kouzmin. 2003.

Reinventing the Democratic Governance Project through Information Technology? Public Administration Review 63(1): 44–60.

Krause, Rachel M. 201 1. Symbolic or Substantive Policy? Measuring the Extent of Local Commitment to Climate Protection. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 29(1): 46–62.