Association between mitral annulus calcification and aortic

atheroma: a prospective transesophageal echocardiographic study

Yehuda Adler *, Mordehay Vaturi, Noam Fink, David Tanne, Yaron Shapira,

Daniel Weisenberg, Noga Sela, Alex Sagie

Cardiology Department,The Scheingarten Echocardiography Unit,Rabin Medical Center,Beilinson Campus,

Petah Tiq6a and Sackler Faculty of Medicine,Tel A6i6 Uni6ersity,Petah Tiq6a49 100Tel A6i6,Israel

Received 30 June 1999; received in revised form 12 October 1999; accepted 1 December 1999

Abstract

Background and purpose: Although mitral annulus calcification (MAC) has been reported to be a significant independent predictor of stroke, no causative relationship was proven. It is also known that aortic atheroma (AA), especially those ]5 mm thick and/or protruding and/or mobile are associated with stroke. This study was designed to determine whether an association exists between MAC and AA. Methods: We prospectively evaluated the records of 279 consecutive patients who underwent transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) for various indications to measure the presence and characteristics of AA. The 105 patients in whom a diagnosis of MAC was made on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) immediately preceding the TEE, were compared with 174 age-matched patients without MAC. MAC was defined as a dense, localized, highly reflective area at the base of the posterior mitral leaflet. We measured MAC thickness with two-dimensional-TTE in four-chamber view and AA thickness, protrusion and mobility with TEE. AA was defined as localized intimal thickening of ]3 mm. A lesion was considered complex if there was plaque extending ]5 mm into the aortic lumen and/or if it was protruding, mobile or ulcerated. Results: No differences were found between the groups in risk factors for atherosclerosis or in indications for referral for TEE. Significantly higher rates were found in the MAC group for prevalence of AA (91 vs. 44%,PB0.001), atheromas ]5 mm thick (68 vs. 19%, PB0.001), protruding atheromas (44 vs. 15%,PB0.001), ulcerated atheromas (10 vs. 1%,PB0.001) and complex atheroma (74 vs. 22%,PB0.001). Sixty patients had MAC thickness ]6 mm and 45B6 mm. AA thickness was significantly greater in the patients with a MAC thickness of ]6 mm (6.192.8 vs. 5.092.6 mm,P=0.03). On multivariate analysis MAC, hypertension and age were the only independent predictors of AA (P=0.0001, 0.005 and 0.007, respectively).Conclusions: There is a significant association between the presence and severity of MAC and AA. MAC may be an important marker for atherosclerosis of the aorta. This association may explain in part the high prevalence of systemic emboli and stroke in patients with MAC. © 2000 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Mitral annulus calcification; Aortic atheroma; Atherosclerosis; Stroke

www.elsevier.com/locate/atherosclerosis

1. Introduction

Calcification of the mitral annulus is a non inflamma-tory, chronic, degenerative process of the fibrous sup-port structure of the mitral valve [1 – 3]. It occurs more often in women and the elderly [4], especially in the presence of systemic hypertension [2,5 – 7], hypercholes-terolemia [5] and diabetes mellitus [5 – 7]. Mitral an-nulus calcification (MAC) has been found to play a role

in left atrial enlargement, left ventricular enlargement, atrial fibrillation, conduction defects, mitral regurgita-tion, mitral stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and bacterial endocarditis [3,8 – 14]. Its association with stroke has been suspected [1 – 3,10 – 24] since the 1946 report of Rytand and Lipsitch [9]. In 1981, Nair et al [3] followed two groups of age-and sex-matched patients (n=107 in each) with and without MAC for a mean of 4.4 years and noted a rate of 10% of cerebrovascular events in the MAC patients as compared with only 2% in the controls (PB0.01). Benjamin et al [25] in a population-based longitudinal study of the

Framing-* Corresponding author. Tel.: +972-3-9377056/7; fax: + 972-3-9377055.

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of MAC subjects and controlsa

Control group (n=174) Pvalue MAC group (n=105)

Cigarette smoking 27 (26%) NS

41 (24%)

25 (24%) NS

Diabetes mellitus

21 (12%) NS

Family history of CHD 18 (17%)

27 (16%) NS

21 (20%) Hypercholesterolemia (\200 mg/dl)

aMAC, Mitral annulus calcification; NS, Not significant; CHD, Coronary heart disease.

ham cohort, found that MAC was associated with a double risk of stroke in the elderly regardless of tradi-tional stroke risk factors. However, whether MAC con-tributes causally to the risk of stroke or is merely a marker of increased risk because of its association with other precursors of stroke remains unclear.

Aortic atheromas (AA), especially those ]5 mm thick [26,27], protruding [28 – 30], ulcerated [31] and mobile [32], have been linked to a higher prevalence of stroke both in retrospective and prospective studies. Thrombi, fibrinous material and cholesterol crystals may dislodge atherosclerotic plaque within the aorta and result in cerebral or peripheral embolism [30]. In a recent preliminary retrospective study, we found a sig-nificant association between the presence of MAC and AA [33].

The aim of the present work was to determine prospectively whether an association exists between MAC and AA, as detected by transesophageal echocar-diography (TEE).

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

Between 1997 and 1999, our laboratory prospectively followed 279 consecutive patients who underwent TEE, excluding patients with rheumatic valvular disease or prosthetic valves. The patients were divided into two groups: 105 patients in whom a diagnosis of MAC was made by transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) per-formed immediately before the TEE (45 females, 60 males, mean age 74910 years, ranged 35 – 93 years) and 174 age-matched patients without MAC (58 fe-males, 116 fe-males, mean age 7297 years, ranged 61 – 92 years). In order to reach age-matching patients younger than 60 years were excluded from the control group before recruitment. The clinical characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1 and the indications for referral for TEE in Table 2.

2.2. Echocardiography study

Complete transthoracic two-dimensional Doppler color flow examinations were performed in all patients using a Hewlett – Packard phased array sector scanner with a 2.5 MHz transducer (77020A). Transesophageal two-dimensional echocardiography was performed im-mediately after the TTE with a commercially available 5 MHz multiplane transducer (Hewlett – Packard 21363A). The sonographs used were Hewlett – Packard Sonos 1000 and 2000. After the cardiac examination, the transducer was rotated posteriorly to obtain aortic images. The transducer was advanced to the distal esophagus (:40 cm) and slowly withdrawn to obtain images from the distal thoracic aorta to the aortic arch; it was then rotated and advanced to image the ascend-ing aorta. If abnormalities of the aorta were detected, more detailed scanning at that level was performed. These procedures are part of our routine TEE examina-tion. All studies were recorded on super-VHS tape and evaluated independently by two specialists in echocar-diography. In cases of disagreement, a third examiner was consulted. MAC was defined as a dense, localized, highly reflective area at the base of the posterior leaflet

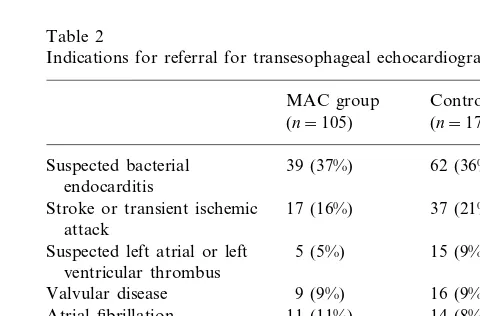

Table 2

Indications for referral for transesophageal echocardiographya

Control group* MAC group

(n=174) (n=105)

Suspected bacterial 39 (37%) 62 (36%) endocarditis

Stroke or transient ischemic 17 (16%) 37 (21%) attack

15 (9%) Suspected left atrial or left 5 (5%)

ventricular thrombus

Congestive heart failure 5 (5%) 3 (2%) 5 (5%)

Suspected aortic dissection 16 (9%)

Others 5 (5%) 4 (2%)

aMAC, Mitral annulus calcification.

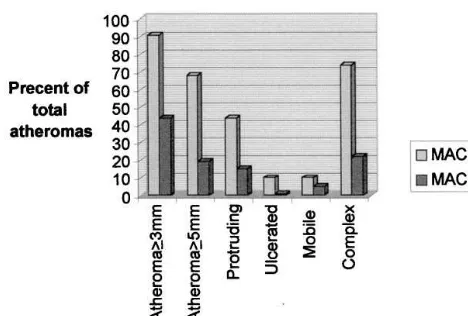

Fig. 1. Prevalence and characteristics of aortic artheromas in patients with and without mitral annulus calcification (MAC).

pharmacologic therapy. Hypertension was defined as either systolic or diastolic elevation in blood pressure (\140/90 mmHg) or ongoing antihypertensive phar-macologic therapy. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as a total cholesterol level of \200 mg/dl. Family history was coded as positive if a first-degree relative had a coronary event at B55 years. Ten or more pack-years of cigarette use was considered significant.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Numeric values are reported as mean9S.D. or as a proportion of the sample size. Comparisons between the study and control group were made with x-square

for categorical data and Student’st-test for continuous data. Multivariate analyses were used to identify pre-dictors for AA. The following variables were entered into the model: age, sex, MAC, diabetes mellitus, hy-pertension, hypercholesterolemia, positive family his-tory and smoking hishis-tory. The univariate correlation coefficients for these variables were determined and were then entered into a multivariate model for predic-tion of AA with use of the RS1 statistical package version 5.3.0 (Bolt, Beranek and Newman, 1997). For-ward stepping was used, with the F to enter and F to remove any variable selected so that the corresponding significance level (outer tail area) was B0.05; no vari-ables were forced into the model.

3. Results

There were no intergroup differences in risk factors for atherosclerosis (Table 1) or in indications for refer-ral for TEE (Table 2). There were significantly more women in the MAC group than in the control group (43 vs. 33%, P=0.038).

Table 3 and Fig. 1 compare the two groups for prevalence and characteristics of AA. Significantly higher rates were found in the MAC group for presence of AA (]3 mm) (91 vs. 44%, PB0.001), atheromas

]5 mm (68 vs. 19%,PB0.001), protruding atheromas (44% vs. 15%, PB0.001) and ulcerated atheromas (10 vs. 1%, PB0.001). Complex atheromas were also of the mitral valve and was evaluated for both presence

and severity (Fig. 1) [34]. The severity of MAC (ex-pressed as maximal thickness in millimeters) was mea-sured with a two-dimensional TTE in four-chamber view [25].

The aortic intima was evaluated for changes in thick-ening, calcification, protrusion, mobility and ulceration. AA was defined as localized intimal thickening of ]3 mm and was localized to the ascending aorta, the aortic arch or the descending aorta. Complex atherosclerotic plaque was defined as the presence of one or more of the following: (1) focal increase in echo density and thickening of the intima extending ]5 mm into the aortic lumen; (2) disruption or irregularities of the intimal surface (ulceration); (3) overlying, shaggy echo-genic material; (4) mobile component of the atheroma; and (5) protruding atheroma [26,35]. The observers who made the diagnosis of AA were blinded to the presence of MAC.

2.3. Risk factors

The atherosclerotic risk factors considered in this study were diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholes-terolemia, family history of coronary heart disease and smoking history. Diabetes was defined as hyper-glycemia requiring previous or the need for ongoing

Table 3

Prevalence and characteristics of aortic atheroma in patients with and without mitral annulus calcificationa

MAC group (n=105) Control group (n=174) Pvalue

96 (91%)

Aortic atheroma (]3 mm) 77 (44%) B0.001

39 (22%) B0.001

78 (74%) Complex atheroma

33 (19%) 71 (68%)

Atheroma]5 mm B0.001

B0.001 46 (44%)

Protruding atheroma 26 (15%)

10 (10%)

Ulcerated atheroma 2 (1%) B0.001

10 (10%) 8 (5%

Atheromas with mobile components 0.1

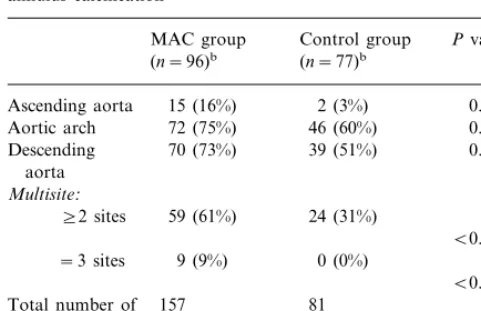

Table 4

Distribution of aortic atheromas in patients with and without mitral annulus calcificationa

MAC group Control group Pvalue (n=77)b Total number of 157 81

lesions

aMAC, Mitral annulus calcification.

bTotal number of patients with atheromas in each group.

Percent-ages andPvalues are calculated from the total number of patients with atheromas in each group.

MAC has long been suspected to be associated with stroke [1,2,9 – 24]. Nair et al [3], in a 4.4-year study of 107 MAC patients aged B61 years and an equal number of age and sex-matched control subjects, found that the MAC patients had a five-fold higher incidence of cerebrovascular events. Aronow et al [36] followed 976 MAC patients (mean age 82 years) for 39 months and noted that MAC was associated with a 1.7 times greater risk of new thromboembolic stroke. In a second study of elderly patients with extracranial carotid arte-rial disease, these authors reported that the presence of MAC increased the incidence of new thromboembolic stroke by 1.5-fold in those with 40 – 100% extracranial carotid arterial stenosis and by 2.2-fold in those with 0 – 39% stenosis [37]. In the Boston Area Anticoagula-tion Trial for Atrial FibrillaAnticoagula-tion [24], a 2.2-year follow-up of 420 patients (mean age 68 years), MAC was found to increase the incidence of ischemic stroke 4.0 times. Finally, Benjamin et al [25] examined the rela-tionship between MAC and the incidence of stroke in a longitudinal population-based study in elderly patients from the Framingham cohort. They concluded that MAC was associated with a double risk of stroke, independently of traditional risk factors for stroke; on multivariate analysis, each millimeter of calcification increased the relative risk of stroke by 1.24 (95% CI, 1.12 – 1.37; PB0.001). Yet, whether such calcification contributes causally to the risk of stroke or is merely a marker of increased risk because of its association with other precursors of stroke remains unknown.

Experimentally-induced systemic arterial atheroscle-rosis is associated with the deposition of fatty plaques on the aortic surface of the aortic valve cusps and on the ventricular surface of the posterior mitral leaflet [38], Roberts [39], in a necropsy study of persons aged

\65 years, showed that 100% of those with MAC or aortic valve calcification had calcific deposits in one or more coronary arteries. This finding was supported by pathological studies [38] showing that collections of foam cells, which represent early atherosclerotic lesions [40] may be observed on the endothelium of the epicar-dial coronary arteries, on the ventricular surface of the posterior mitral leaflet and on the aortic aspects of each of the aortic valve cusps already in adolescence and the second and third decades of life. These data suggest that coronary atherosclerosis, MAC and aortic valve calcium in the elderly have a similar etiology. As the fatty plaques get larger, their nutritional needs fail to be fulfilled and they degenerate into calcific deposits. Roberts [40] claimed, in an editorial on the senile cardiac calcification syndrome, that because calcific de-posits in the mitral annular area are observed only in a population that develops significant coronary atherosclerosis, it is reasonable to assume that the cause of MAC in the elderly is similar; that is, MAC in the elderly is a form of atherosclerosis. This explains the found significantly more often in the MAC group (74

vs. 22%, PB0.001). The presence of atheroma with a mobile component was not statistically significant (10 vs. 5%, P=0.1). The distribution of atheromas along the aorta is shown in Table 4. There were significantly more patients in the MAC group with diffuse athero-mas in the aorta, including the ascending, arch and descending aorta in the same patient (9 vs. 0%, PB

0.001). When comparing only atheromas in the ascend-ing aorta and aortic arch, we also found a significant difference between the two groups (91 vs. 62%, PB

0.001).

In the MAC group 60 patients had a MAC thickness of ]6 mm and 45 patients a thickness of B6 mm. AA thickness was significantly greater in the patients with MAC thickness of ]6 mm (6.192.8 mm vs. 5.0 9

2.6 mm, P=0.03). On multivariate analysis MAC, hypertension and age were the only independent predic-tors of AA (P=0.0001, 0.005 and 0.007, respectively). MAC emerged as the most powerful predictor identified for AA.

4. Discussion

coexistence of MAC and aortic atheroma in the same patients.

We recently demonstrated a significant association between MAC and carotid atherosclerotic disease [41], a well known risk factor for stroke. In a different study we found a highly significant association between MAC and coronary artery disease, including higher rates of 3-vessel disease and left main coronary artery disease among patients with MAC [42]. As a result of the body of evidence obtained from cased control and follow-up studies [26 – 32], the presence of plaques in the aortic arch can be accepted as a strong independent risk factor for brain infarction, with a causal relationship, particularly for large complex plaques. The significant association between the prevalence and severity of MAC and AA support the view that MAC is a marker of diffuse atherosclerosis, affecting both the aortic arch and the carotid arteries, both capable of causing stroke. Moreover, our results may explain the finding of Ben-jamin et al [25] regarding the correlation between MAC thickness and the relative risk of stroke.

The absence in our work of any significant differ-ences in risk factors between the MAC group and the controls and the finding on multivariate analysis that only MAC, age and hypertension were an independent predictors for aortic atheroma, further support our hypothesis that MAC and aortic atheroma are an ex-pression of the same systemic process. It is not surpris-ing that the MAC group had significantly more women than the controls. It has been well established that MAC occurs more often in women [4] and our results confirm this finding.

In conclusion, MAC can be detected by TTE, a simple, non invasive imaging method. Using MAC as a marker, can define a subgroup of patients with a very high prevalence of AA. We suspect the association between MAC and atherosclerosis, including aortic atheroma and carotid atherosclerotic disease explains the high incidence of stroke in MAC patients. The presence of MAC probably indicates a systemic atherosclerotic process which involves the aorta, aortic valve, carotid and coronary arteries and perhaps other parts of the arterial systems. This mounting evidence suggests that MAC should likely be considered, in most cases, as an atherosclerotic comorbidity in stroke and not its cause [43].

References

[1] Korn D, DeSanctis RW, Sell S. Massive calcification of the mitral annulus: a clinicopathological study of fourteen cases. New Engl J Med 1962;267:200 – 9.

[2] Fulkerson PK, Beaver BM, Auseon JC, Graber HL. Calcifica-tion of the mitral annulus: etiology, clinical associaCalcifica-tion, compli-cations and therapy. Am J Med 1979;66:967 – 77.

[3] Nair CK, Thomson W, Ryschon K, et al. Long term follow-up of patients with echocardiographically detected mitral annulus calcium and comparison with age and sex-matched control sub-jects. Am J Cardiol 1989;63:465 – 70.

[4] Savage DD, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Ander-son SJ. Prevalence of submitral (annular) calcium and its corre-lates in a general population-based sample (the Framingham study). Am J Cardiol 1983;51:1375 – 8.

[5] Waller BP, Roberts WC. Cardiovascular disease in the very elderly. An analysis of 40 necropsy patients aged 90 years or over. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:403 – 21.

[6] Roberts WC, Perloff JK. Mitral valvular disease: a clinicopatho-logic survey of the condition causing the mitral valve to function abnormally. Ann Intern Med 1972;77:939 – 75.

[7] Aronow WS, Schwartz KS, Koenigsberg M. Correlation of serum lipids, calcium and phosphorus, diabetes mellitus, aortic valve stenosis: a history of systemic hypertension with presence or absence of mitral annular calcium in persons older than 62 years in a long-term health care facility. Am J Cardiol 1997;59:381 – 2.

[8] Aronow WS. Mitral annular calcification: significant and worth acting upon. Geriatrics 1991;46:73 – 86.

[9] Rytand DA, Lipsitch LS. Clinical aspects of calcification of the mitral annulus fibrosus. Arch Intern Med 1946;78:544 – 64. [10] Zak FG, Elias K. Embolization with material from atheromata.

Am J Med Sci 1949;218:510 – 5.

[11] Ridolfi RL, Hutchins GM. Spontaneous calcific emboli from calcific mitral annulus fibrosus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1976;100:117 – 20.

[12] Furlan AJ, Cracium AR, Salcedo EE, Mellino M. Risk of stroke in patients with mitral annulus calcification. Stroke 1984;15:801 – 5.

[13] Lim CS, Schawtz IS, Chapman I. Calcification of the mitral annulus fibrosus with systemic embolization: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Arch Lab Med Pathol 1987;111:411 – 4. [14] Kirk RS, Russell JGB. Subvalvular calcification of mitral valve.

Br Heart J 1969;31:684 – 92.

[15] Burnside JW, DeSanctis RW. Bacterial endocarditis on calcifica-tion of the mitral annulus fibrosus. Ann Intern Med 1972;76:615 – 8.

[16] Greenland P, Knopman DS, Mikell FL, et al. Echocardiography in diagnostic assessment of stroke. Ann Intern Med 1981;95:51 – 3.

[17] Good DC, Frank S, Verhulst S, Sharma B. Cardiac abnormali-ties in stroke patients with negative arteriograms. Stroke 1986;17:6 – 11.

[18] Todnem K, Vik-Mo H. Cerebral ischemic attacks as a complica-tion of heart disease: the value of echocardiography. Acta Neu-rol Scand 1986;74:323 – 7.

[19] Rem JA, Hachinski VC, Boughner DR, Barnett HJM. Value of cardiac monitoring and echocardiography in TIA and stroke patients. Stroke 1985;16:950 – 6.

[20] Bogousslavsky J, Hachinski VC, Boughner DR, Fox AJ, Vineula F, Barnett HJM. Cardiac and arterial lesions in carotid transient ischemic attacks. Arch Neurol 1986;43:223 – 8.

[21] De Bono DP, Warlow CP. Mitral annulus calcification and cerebral or retinal ischaemia. Lancet 1979;2:383 – 5.

[22] Jespersen CM, Egeblad H. Mitral annulus calcification and embolism. Acta Med Scand 1987;222:37 – 41.

[23] Nishide M, Irino T, Gotoh M, Naka M, Tsuji K. Cardiac abnormalities in ischemic cerebrovascular disease studied by two-dimensional echocardiography. Stroke 1983;14:541 – 5. [24] The Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation

[25] Benjamin EJ, Plehn JF, D’Agostino RB. et al. Mitral annular calcification and the risk of stroke in an elderly cohort. N Engl J Med 1992;327:374 – 9.

[26] Katz ES, Tunick PA, Rsinek H, et al. Protruding aortic atheromas predict stroke in elderly patients undergoing car-diopulmonary bypass: experience with intraoperative trans-esophageal echocardiography. JACC 1992;20:70 – 7.

[27] Tunick PA, Rosenzweig BP, Katz ES, et al. High risk for vascular events in patients with protruding aortic atheromas: a prospective study. JACC 1994;23:1085 – 90.

[28] Tunick PA, Kronzon I. Protruding atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic arch of patients with systemic embolization: a new finding seen by transesophageal echocardiography. Am Heart J 1990;120:658 – 60.

[29] Tunick PA, Perez JL, Kronzon I. Protruding atheromas in the thoracic aorta and systemic embolization. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:423 – 7.

[30] Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, Ross JJ, Mintz GS. The recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. JACC 1991;17:73 – 8.

[31] Amarenco P, Duyckaertz C, Tzourio C, et al. The prevalence of ulcerated plaque in the aortic arch in patients with stroke. New Engl J Med 1992;326:221 – 5.

[32] Horowitz DR, Tuhrim S, Budd J, Goldman ME. Aortic plaque in patients with brain ischemia. Neurology 1992;42:1602 – 4.

[33] Adler Y, Zabarski RS, Vaturi M, et al. The association be-tween mitral annulus calcium and aortic atheroma as detected by transesophageal echocardiography study. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:784 – 6.

[34] D’Cruz I, Panetta F, Cohen H, Glick G. Submitral calcifica-tion or sclerosis in elderly patients: M-mode and

two-dimen-sional echocardiography in ‘mitral annulus calcification’. Am J Cardiol 1979;44:31 – 8.

[35] Khoury Z, Gottlieb S, Stern S, Keren A. Frequency and dis-tribution of atherosclerotic plaques on the thoracic aorta as determined by transesophageal echocardiography in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:23 – 7. [36] Aronow WS, Koenigsberg M, Kronzon I, Gutstein H.

Associ-ation of mitral annular calcium with new thromboembolic stroke and cardiac events at 39-month follow-up in elderly patients. Am J Cardiol 1990;65:1511 – 2.

[37] Aronow WS, Schoenfeld MR, Gutstein H. Frequency of thromboembolic stroke in persons (60 years of age with ex-tracranial carotid arterial disease and/or mitral annular cal-cium. Am J Cardiol 1992;70:123 – 4.

[38] Thubrikar MJ, Deck JD, Aduad J, Chen JM. Intramural stress as a causative factor in atherosclerotic lesion of the aortic valve. Atherosclerosis 1985;55:299 – 311.

[39] Roberts WC. Morphologic features of the normal and abnor-mal mitral valve. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:1005 – 28.

[40] Roberts WC. The senile cardiac calcification syndrome. Am J Cardiol 1986;58:572 – 4.

[41] Adler Y, Koren A, Fink N, et al. Association between mitral annulus calcification and carotid atheroscleroticdisease. Stroke 1998;29:1833 – 7.

[42] Adler Y, Herz I, Vaturi M, et al. Mitral annulus calcium detected by transthoracic echocardiography is a marker for high prevalence and severity of coronary of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:1183 – 6.

[43] Adler Y, Tanne D, Sagie A. Mitral annulus calcification and carotid atherosclerotic disease: letter to the editor. Stroke 1999;30:693.