Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

Is autism spectrum disorder common in schizophrenia?

Maria Unenge Hallerbäck

a,b,⁎

, Tove Lugnegård

b,c, Christopher Gillberg

b aDepartment of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Central Hospital, 651 85 Karlstad, Sweden

bGillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

cDepartment of Adult Habilitation, Central Hospital, Karlstad, Sweden, and Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

a b s t r a c t

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 31 August 2011

Received in revised form 1 December 2011 Accepted 13 January 2012

Keywords:

Psychosis Asperger syndrome DISCO

SCID

A century ago, Kraepelin and Bleuler observed that schizophrenia is often antedated by“premorbid” abnor-malities. In this study we explore how the childhood neurodevelopmental problems found in patients with schizophrenia relate to the current concept of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Forty-six young adult individuals with clinical diagnoses of schizophrenic psychotic disorders were assessed. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID-I) was used in face-to-face psychiatric examination of each individual. In 32 of the 46 cases (70%), collateral information was provided by one or both parents. The Diagnostic Interview for Social and Com-munication Disorders—eleventh version (DISCO-11) was used when interviewing these relatives. This instru-ment covers, in considerable depth, childhood developinstru-ment, adaptive functioning, and symptoms of ASD—

current and lifetime. There is a strict algorithm for ASD diagnosis. About half of the cases with schizophrenic psychosis had ASD according to the results of the parental interview. The rate of ASD was strikingly high (60%) in the group with a SCID-I diagnosis of schizophrenia paranoid type. Thefindings underscore the need to revisit the DSM's“either or”stance between ASD and schizophrenia.

© 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Although the typical symptoms of schizophrenia usually appear in young adulthood, precursors of the disorder may be present during childhood. Children who, in their late teens or adulthood, develop schizophrenia have been described as slightly different from their age peers with regard to motor performance, cognitive development, activity control and social interaction. Even though there have been many of studies of these phenomena, the nature of the neurodevelop-mental deviations is still poorly understood.

In the prospective study of the British 1946 birth cohort, differ-ences between children who developed schizophrenia as adults and the general population were found in a range of developmental do-mains. Speech problems, low educational test scores, solitary play preference, and self-reported anxiety in social situations during child-hood were factors associated with schizophrenia in adultchild-hood (Jones et al., 1994). Another extensive cohort-study, the National Child De-velopment Study, found that individuals who later developed schizo-phrenia differed from schoolmates in several social and emotional domains (Done et al., 1994; Leask et al., 2002). Deviant behaviours at age 4 years and both social and language impairment by age 7 years were found in another prospective cohort study by (Bearden et al., 2000).

Home-videos of patients with schizophrenia as children have been analysed in comparison with siblings in a unique study by Elaine Walker (Walker et al., 1993, 1994). According to this, children who later developed schizophrenia showed more negative emotions and frequently had unusual motoric features compared with their healthy siblings. In 1972 a sample of young Danish children (age 11–13) were videotaped in a standardized condition as part of the Copenhagen High-Risk Study (Schiffman et al., 2004). Adult psychiatric status was later ascertained. The analysis of the videotapes showed that the individuals who developed schizophrenia, as a group, showed deficits in sociability.

Given that genetics are important risk factors for schizophrenia, several high-risk studies have longitudinally followed children who have one or two parents with schizophrenia. Problems in motor and neurological development, deficits in attention and verbal short-term memory, and poor social competence are factors that appear to predict schizophrenia in these studies (Erlenmeyer-Kimling and Cornblatt, 1987; Mednick et al., 1987; Weintraub, 1987; Erlenmeyer-Kimling et al., 2000; Niemi et al., 2003).

Greater awareness about children's circumstances and of the con-sequences of neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood has led to an increased concern regarding early identification and support of children with such difficulties. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is considered as a neurodevelopmental disorder with a spectrum of signs and symptoms, the essential features being a triad of impair-ments of social interaction, communication and imagination. ASD is recognised in children with normal as well as subnormal intelligence. ASD was, until recently, assumed to be a rare condition, but according ⁎Corresponding author. Tel.: +46 54 618301; fax: +46 54189491.

E-mail address:maria.hallerback@liv.se(M. Unenge Hallerbäck). 0165-1781/$–see front matter © 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.01.016

Contents lists available atSciVerse ScienceDirect

Psychiatry Research

to recent epidemiologic studies using DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria, the prevalence of ASD is 0.5–1% of the child population (Baird et al., 2006; Fombonne et al., 2009). Symptoms should be present from in-fancy or early childhood, but they may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities (www.dsm5.org). Au-tism is now diagnosed for thefirst time in adults and even in elderly people (van Niekerk et al., 2010). This confirms that although autism is present from childhood, it is not always recognized and addressed during the early years.

Genetic studies have shown numerous direct and indirect links between ASD and schizophrenia (McCarthy et al., 2009; Craddock and Owen, 2010). Specific copy number variants associated with schizophrenia are also linked to a range of neurodevelopmental dis-orders including ASD, intellectual disability and ADHD (Owen et al., 2011). Neurexin-1, a vulnerability gene for both schizophrenia and ASD, has been proposed to influence brain structure and cognitive function susceptible in both disorders (Voineskos et al., 2011). Family history data support a link between ASD and schizophrenia (Ghaziuddin, 2005).

Neuroimaging studies have shown appreciable brain structural con-cordances between autism and schizophrenia (Cheung et al., 2010). In a magnetic resonance imaging study byToal et al. (2009)adults with ASD with or without a history of psychosis and healthy controls were com-pared. The group with ASD differed from controls in brain regions that are also implicated in schizophrenia. The authors put forward ASD as an alternative‘entry-point’into schizophrenia based on developmental brain abnormalities, suggesting that people with ASD may only require relatively subtle additional abnormalities to develop the positive symp-toms of psychosis such as delusions and hallucinations.

Childhood onset schizophrenia, i.e. schizophrenia with onset prior to the age of 13 years, is a rare, very severe condition with poor long-term prognosis. It is antedated by (and“comorbid”with) ASD in 30– 50% of the cases (Sporn et al., 2004; Rapoport et al., 2009).

The aim of the present study was to examine the rate of ASD in pa-tients with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, to analyse whether or not ASD is more common in any particular subtype of schizophre-nia or if any specific subtype of ASD is more strongly related to schizophrenia, and to evaluate the effect, if any, of gender on any pos-sible association between the two categories.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Subjects

The study group consisted of 46 young adult patients (29 male, 17 female) with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder or schizoaffective disor-der, henceforth referred to as schizophrenic psychoses.

Subjects werefirst recruited from the only adult psychiatric clinic in the county of Värmland, Sweden. Our original aim was to locate every patient in Värmland with schizophrenic psychosis born between 1972 and 1986, and to invite 30 men and 30 women from this cohort to participate in the study (which is part of a broader study of similarities and differences across schizophrenia and Asperger syndrome). Individuals with diagnosed intellectual disability would not be included.

In Värmland all adult psychiatric services were in the public domain at the time of the study and organized at the county level into one clinic. Staff members at the differ-ent psychiatric out-patidiffer-ent departmdiffer-ents around the county were informed about the study and asked to screen their service for patients with schizophrenic psychosis. They were asked to inform the patient about the study, to give a standard (oral and written) full description of the study (approved by the Ethics committee, see below). Patients who did not have a current contact were sent a participation inquiry. Individuals with currentseverepsychotic symptoms requiring hospitalisation were approached when symptoms were considered lessflorid. Patients accepting to participate were included only after written informed consent had been received from each individual. Because of recruitment difficulties, we decided to include three individuals with schizophrenia born in the beginning of 1987.

In due course, a total of 84 patients, 58 men and 26 women, were deemed eligible for the study. Thirty men from Värmland (52% of the whole eligible group) accepted to participate, but two of them withdrew before thefirst assessment. Seventeen women from Värmland (65% of all eligible women) accepted to participate. Two of them chan-ged their mind before entering the study. One woman was excluded because the diag-nosis was not confirmed by a psychiatrist. Thus, 28 men and 14 women with

schizophrenic psychosis from Värmland participated in the study. In order to increase the number of participants, we approached an outpatient clinic for patients with psy-chosis in the city of Gothenburg, from which we unfortunately only managed to recruit one man and three women.

We compared the number of eligible patients from Värmland in our study with re-sults from another study, a nation-wide Swedish study using register data, performed by Hultman and colleagues as part of the International Schizophrenia Consortium study (ISC, 2008). In that study cases were identified via the Swedish Hospital Dis-charge Register, which contains a register of all individuals hospitalized in Sweden since 1973. Each record contains the main discharge diagnosis, and secondary diagno-ses. Patients with discharge diagnoses of schizophrenia who had at least two admis-sions were included. From the county of Värmland a total of 80 individuals (50 men and 30 women) born in our target years 1972–1986 met these criteria. In contrast to our study, subnormal intelligence was not an exclusion criterion. Numbers are not widely discrepant from those that we found, providing some support for the notion that our eligible group of participants is as close to a representative sample of individuals with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenic psychosis as would be possible to identify and contact in a general population setting. According to these numbers, the prevalence of schizophrenic psychosis in Värmland for persons born in 1972 to 1986 was 0.2%.

2.2. Parents

Once included and contacted, the participants were asked for permission for us to contact their parents for an interview. Five participants did not give such permission. The other parents were contacted by mail with a separate participation inquiry. Parents of 21 men and 11 women accepted to participate and were interviewed.

2.3. Instruments used 2.3.1. SCID

All participants included had a definite or (in a few cases) preliminary clinical diagno-sis of schizophrenic psychodiagno-sis. In order to confirm these diagnoses, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (First and Gibbon, 2004) was used in face– to face interview with the participants (by the second author).

2.3.2. WAIS-III

Global intellectual ability was measured using the full-scale Swedish version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III (Wechsler, 1997). Ten participants were not able to participate in this testing due to practical reasons (for example: difficulties coming to the clinic at a set time, being overwhelmed by the thought of being tested). A full WAIS-III protocol was included for 21 men and 15 women.

2.3.3. DISCO-11

Since patients with schizophrenia often have marked difficulties in social interac-tion and communicainterac-tion along withflat affect due to negative symptoms, we decided not to assess the probands directly for ASD. There would be a marked risk that diffi cul-ties that are secondary to schizophrenia would be rated as primary deficits in social in-teraction and communication. Instead we focused on examining any presence of ASD during childhood and adolescence. Parents were interviewed with the Diagnostic In-terview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO-11) (Wing et al., 2002). The DISCO is a semi-structured interview and covers a wide range of developmental do-mains. An algorithm is included for different diagnostic categories: ICD-10 criteria for Autism, Asperger syndrome, Atypical autism with atypical onset age and/or atypical symptoms (World Health Organization, 2004), Kanner and Eisenberg criteria for Au-tism (Eisenberg and Kanner, 1956), Gillberg criteria for Asperger syndrome (Ehlers and Gillberg, 1993), and Wing and Gould criteria for Autistic spectrum disorder (Wing and Gould, 1979). The DISCO schedule is investigator based; the interviewer is to elicit enough information from the informant to make a judgement as to the most appropriate rating for each item. The interviewer is to encourage the informant to describe examples of behaviour or to relate illustrative anecdotes. Since recall of the timing of events is much less reliable than the memory of their occurrence, the age when a specific behaviour occurred is not coded, apart from a few items concern-ing developmental skills. The interviewer is to code behaviour that the informant re-members easily and clearly. If informants have to search their memory and remain uncertain, the item is coded as absent or not known. The interview is structured to col-lect information about the current situation (“current”) as well as information about development and previous (“ever”) behaviour. In the present study, one primary aim was to explore the behaviour during childhood development. Hence, in scoring the DISCO-11, the score“ever”was consistently usedonly for earlier behaviour, meaning that if behaviour was currently present but was not present during childhood it would be scored only as“current”.

Another adaptation of the DISCO-11 was to leave out the questions about schizo-phrenia. Schizophrenia is an exclusion criterion for autism in the algorithm which would preclude examination of whether or not the two conditions might co-exist.

The psychometric properties, including inter-rater reliability, of both the original and the Swedish version of the DISCO are excellent according to methodological stud-ies (Leekam et al., 2002; Nygren et al., 2009). The criterion validity is excellent when compared with clinical diagnosis as well as compared to another frequently used diag-nostic interview, the Autism Diagdiag-nostic Interview, ADI (Lord et al., 1994; Nygren et al., 2009). One advantage of the DISCO in comparison with the ADI is that it includes

valuable information about the broader autism phenotype. Thefirst author, who car-ried out the DISCO-interviews, was trained in the DISCO's administration by the origi-nators of the English and the Swedish versions of the interview.

2.3.4. Autism spectrum quotient (AQ)

As a complement to the parent interview, the Autism Quotient (AQ) (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001) was used. The AQ is a self-administered questionnaire developed for the explicit purpose of measuring autistic traits in adults of normal intelligence to assess autistic traits. The AQ is widely used in clinical settings as well as in research to screen for autism spectrum disorders. Participants rate to what extent they agree or disagree with 50 different statements about personal preferences and habits on a 4-point Likert scale. All the item scores are summed, which gives a maximum score of 50. A high AQ score has been proposed to indicate a likely diagnosis within the autism spectrum. In this study the mean total score in the group examined with the DISCO is compared to the mean total score in the group not examined in order to evaluate how represen-tative the DISCO examined group is.

2.3.5. Patient records

All participants were asked if they had been in contact with child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP). Four men and seven women recalled such contact and they all gave permission to use their psychiatricfiles in the study. The records were analysed according to age at contact, diagnoses, recorded developmental deviation, and type of care. Data relating to these 11 individuals are presented as short clinical vignettes in the Appendix.

2.3.6. Statistical methods used

Chi-square tests (with Yates' correction whenever appropriate) were used when comparing group frequencies.

2.3.7. Ethics

The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Board at Uppsala.

3. Results

3.1. SCID

The clinical diagnoses were re-evaluated with the SCID. Of the 46 participants, 12 men and 7 women met criteria for schizophrenia paranoid subtype, including one woman and one man who had had episodes of substance induced psychosis in addition to schizophrenia. One woman andfive men met criteria for schizophrenia undifferen-tiated subtype. Two men and six women met criteria for schizoaffec-tive disorder. Three men met criteria for schizophreniform disorder. Five individuals (three men, two women) met criteria for psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, and in two of these the psychosis was deemed to be substance induced. One man had substance in-duced psychosis“only”. Two men did not meet criteria for a psychosis in the schizophrenia spectrum according to the SCID, but met criteria for Bipolar disorder type I instead. For two participants (one man, one woman) psychoses could not be confirmed by the SCID.

3.2. DISCO-ASD-algorithm diagnoses

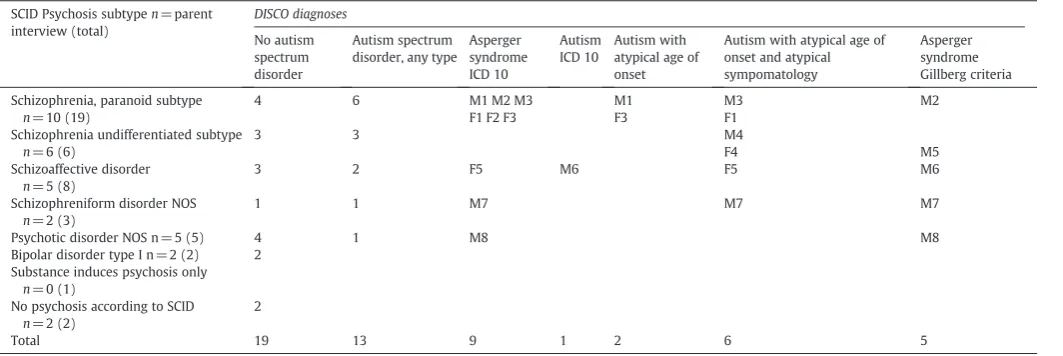

According to the results of the DISCO interview, 41% of the 32 cases examined had an algorithm diagnosis of ASD. Focusing solely on those for whom a schizophrenic psychosis (schizophrenia para-noid or undifferentiated subtype, schizoaffective disorder or schizo-phreniform disorder) was confirmed by the SCID and for whom a DISCO interview was attained, 12 out of 23 (52%) fulfilled criteria for ASD diagnosis according to the DISCO algorithm. The rate of ASD was particularly high (60%) in the group with a SCID diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia (seeTable 1).

The distribution of the different ASD diagnoses was explored. There was a marked overlap between the diagnoses. Nine partici-pants met criteria for more than one ASD diagnosis. One individual had classic autism (F 84.0, ICD 10). Two other individuals also met symptom criteria for classic autism, but parents were not sure about symptoms before age 3 years; hence the diagnosis“Autism with atypi-cal age of onset”(F 84.10, ICD 10) was applied. Six individuals met cri-teria for “Autism with atypical age of onset and atypical symptomatology”(F 84. 12, ICD 10), since, although there had been symptoms of autism during childhood, no clear symptoms before age 3 years were reported, and the autism criteria for communication were not quite met.

In the DISCO diagnostic algorithm, there is a diagnostic hierarchy: if any of the autism diagnoses mentioned above (autism and the variants of atypical autism) are met, then the Asperger syndrome diagnosis (F 84.5, ICD 10) is put in brackets, indicating that the“autism” diagno-sis is regarded as the more appropriate. InTable 1, all those who met criteria for Asperger syndrome as defined in ICD 10 are shown, includ-ing six who also met criteria for atypical autism.

The Gillberg criteria for Asperger syndrome are the only criteria for this disorder that are based on Hans Asperger's case studies (Gillberg and Gillberg, 1989; Gillberg, 1992). Five individuals (all male) met these criteria and thus conformed to the phenotype origi-nally described by Hans Asperger.

3.3. Gender aspects

The intention in the original study protocol had been to include 30 men and 30 women with schizophrenia. Since schizophrenia is rare among young adult women, the typical age of onset being later than in men, we had great difficulties recruiting women. Finally 17 women participated in the study, but parental information was only possible to attain from 11 of them. Five of these 11 (45%) had some

Table 1

Distribution of SCID- DISCO algorithm diagnoses in 32 DISCO examined individuals, M = Male, F= Female.

SCID Psychosis subtypen= parent interview (total)

DISCO diagnoses

No autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder, any type

Asperger syndrome ICD 10

Autism ICD 10

Autism with atypical age of onset

Autism with atypical age of onset and atypical sympomatology

Asperger syndrome Gillberg criteria

Schizophrenia, paranoid subtype

n= 10 (19)

4 6 M1 M2 M3 M1 M3 M2

F1 F2 F3 F3 F1

Schizophrenia undifferentiated subtype

n= 6 (6)

3 3 M4

F4 M5

Schizoaffective disorder

n= 5 (8)

3 2 F5 M6 F5 M6

Schizophreniform disorder NOS

n= 2 (3)

1 1 M7 M7 M7

Psychotic disorder NOS n = 5 (5) 4 1 M8 M8

Bipolar disorder type I n = 2 (2) 2 Substance induces psychosis only

n= 0 (1)

No psychosis according to SCID

n= 2 (2)

2

Total 19 13 9 1 2 6 5

kind of ASD according to the DISCO algorithm, yet none of them met Gillberg criteria for Asperger syndrome.

Twenty-nine men participated, and parents of 21 of them (72% of the men in the study) were interviewed. Eight (38%) had some kind of ASD according to the interviews.

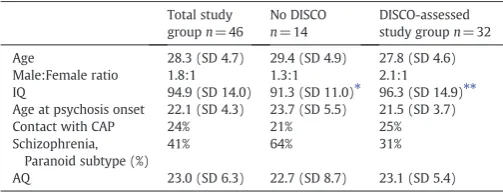

3.4. Effects of attrition from the DISCO-11 part of the study

The relatively largest drop-out rate from DISCO-11 interview with a collateral informant occurred in the subgroup of individuals diag-nosed with paranoid schizophrenia, 9/19 (47%), compared to 5/27 (19%) in the non-paranoid study group, chi-squarep= 0.0036. The following reasons were given for non-participation in the DISCO part of the study in the paranoid subgroup: (1) two individuals did not give permission to contact their parents, (2) parents offive indi-viduals actively declined participation, (3) parents of one individual lived abroad, and (4) parents of one individual never returned the par-ticipation inquiry despite reminders. The DISCO-examined subgroup with paranoid schizophrenia had a very high rate of ASD. The reasons for“DISCO attrition”did not help clarify whether the DISCO-examined subgroup was typical or not of the whole paranoid schizophrenia group. We examined if the participants with psychosis for whom we obtained parental DISCO information differed from those for whom we did not manage to get DISCO data (see Table 2). According to the AQ score, the groups were similar in terms of“degree of ASD”. The age at thefirst appearance of psychosis did not differ. The number of in-patient treatment episodes was compared, and there was no dif-ference between the groups.

3.5. Patient records

The clinical vignettes (see Appendix) from CAP (child and adolescent psychiatry), including three cases (one with paranoid schizophrenia and two with schizoaffective disorder) where parents declined DISCO, exemplify that severe problems during childhood often have preceded the onset of schizophrenia. For some the contact with CAP was very brief; for others contact continued over several years. The reports were from the 1980s and 1990s. None of them had a clear ASD diagnosis rec-ognized during childhood, but the descriptions for some of them are quite characteristic for ASD diagnosis as it is defined today.

4. Discussion

The majorfinding of this study was that about half of cases with a clinical and research diagnosis of a schizophrenic psychosis had ASD according to results obtained at parental DISCO interview. This is a strikingly high proportion, and one clearly at odds with the wide-spread clinical notion that there is little or no overlap between autism and schizophrenia.

Before addressing these results in more detail, we need to stress some important limitations of the study. To begin with, the study

group is small; a replication of the study in a larger sample would be of great value. Despite our original aim to include 30 men and 30 women, only 46 actually participated, and two of these actually did not have psychosis according to the SCID interview. Also, it was more complicated than initially envisaged to get permission from both patient and parent to do the DISCO interview. This was particu-larly problematic in the group with paranoid schizophrenia given that among the 10 individuals who had DISCO-11 results, the rate of diag-nosed ASD was much the highest in the whole study. Old myths about parents causing schizophrenia may be one explanation for the reluc-tance to participate. One parent was openly disappointed at not hav-ing received needed support earlier, and did not want to participate for that reason. This might have been true for other parents. Schizo-phrenia often leads to strain on close relationship and an increased family burden (Lowyck et al., 2004; Hjärthag et al., 2010). Further-more, given that ASDs are more common among men and that the men are in a majority in the study partially due to the young ages of patients included, and some women have yet to develop schizophre-nia, the rates of co-morbid ASDs and schizophrenia spectrum disor-ders found here may have been overestimated.

Using retrospective parental interview for tapping into develop-mental and behavioural problems in the offspring is a method with advantages and disadvantages. Parents often know their children well and may better than anyone describe their strengths and weak-nesses, but recall bias needs to be considered. Certainly, the DISCO provides an opportunity for parents to describe their sons or daugh-ters more fully than do alternative methods such as questionnaires or highly restricted structured interviews. During the interviews, it became apparent that in general, parents were trying hard tofind an explanation for why their child had been affected. Frequently they blamed themselves or circumstances in their life. They some-times tended tofind the questions about peer relationships, commu-nication, and type of early childhood play pattern irrelevant. By encouraging parents to bring photos and starting the interview by let-ting them describe their child prior to school age, the recollection was facilitated, whereafter more direct questions could often be posed.

We decided not to try to assess directly for ASD by observational means, given that there is clearly no appropriate instrument for this purpose in schizophrenia. The most accepted observational instrument for assessing ASD is the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al., 2000; Gotham et al., 2009). The ADOS is a standard-ized instrument that assesses social interaction, communication, and imagination during a semi-structured interaction with the examiner. Since patients with schizophrenia often have difficulties in social inter-action, communication and imagination, a subjective evaluation of these abilities, albeit using a standardised method, may well be biased. Furthermore, it is not possible with the ADOS to differentiate between primary and secondary deficits. In a study by Bastinaansen et al., 93 adult males from four diagnostic subgroups (ASD, schizophrenia, psy-chopathy and typically developing controls) were examined with the ADOS. (Bastiaansen et al., 2011). Both the ASD and the schizophrenia group scored much higher than controls on both the communication and social interaction domains on the ADOS. The authors commented that individuals with schizophrenia and marked negative symptoms show behaviours that are very similar to those shown in ASD. They could not eliminate the possibility that ASD was present before the onset of schizophrenia, but stated that the possibility is minimized by the fact that the individuals were extensively tested in a specialized psychosis centre. However, according to our findings, their results may in fact be interpreted as yet another indication that these condi-tions frequently co-exist.

Several case reports have been published of patients with a diag-nosis of schizophrenia re-evaluated as having ASD. The results of these studies suggest that these disorders overlap from the symptomato-logical point of view (Roy and Balaratnasingam, 2010; van Niekerk et al., 2010; Woodbury-Smith et al., 2010). The patients in our study were Table 2

Study group characteristics including cases assessed using the DISCO.

Total study groupn= 46

No DISCO

n= 14

DISCO-assessed study groupn= 32 Age 28.3 (SD 4.7) 29.4 (SD 4.9) 27.8 (SD 4.6) Male:Female ratio 1.8:1 1.3:1 2.1:1

IQ 94.9 (SD 14.0) 91.3 (SD 11.0)⁎ 96.3 (SD 14.9)⁎⁎ Age at psychosis onset 22.1 (SD 4.3) 23.7 (SD 5.5) 21.5 (SD 3.7)

Contact with CAP 24% 21% 25%

Schizophrenia, Paranoid subtype (%)

41% 64% 31%

AQ 23.0 (SD 6.3) 22.7 (SD 8.7) 23.1 (SD 5.4)

⁎ n= 10. ⁎⁎ n= 26.

recruited on the basis of the clinical diagnosis and the diagnoses were confirmed by a SCID interview. Hence, our results indicate that a con-siderable proportion of those with aclear(clinical and research) diag-nosis of schizophrenia have apparent signs of ASD when an in-depth parent interview is performed. These findings have implications for clinical management of schizophrenia and challenge the existing views about the diagnostic separation between autism and schizophre-nia. According to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), the diagnoses Asperger's disorder, atypical autism and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified are by definition not given if criteria for schizophrenia are met. However, schizophrenia may co-exist with Asperger's disorder if the onset of Asperger's disorder clearly preceded the onset of schizophrenia. This is straightforward if the Asperger's disorder diagnosis has been assessed during childhood, but causes a dilemma for clinicians who meet young adults with clear schizophrenia and with a history of difficulties corresponding with Asperger's disorder (Nylander et al., 2008).

In a Danish study 89 individuals with atypical autism,first seen as children, were followedup through the nationwide Danish Psychiatric Central Register more than 30 years later. Matched controls from the general population were used as a comparison group. Schizophrenia spectrum disorders were the most common associated psychiatric disorders, diagnosed at least once in 35% of the cases compared to 3% in the comparison group (Mouridsen et al., 2008).

Recently, a hypothesis of psychosis and autism as diametrical dis-orders of the social brain has been proposed byCrespi and Badcock (2008). They suggest that individuals with psychosis, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, have superior social cognition, "hyper-mentalistic" cognition, in contrast to the deficits in social cog-nition that are typical in autism. The hyper-mentalistic cogcog-nition leads to delusions of being spied on, paranoid delusions and conspirato-rial delusions etc. Ourfindings do not provide support for this type of spectrum or distinction between autism and psychosis. One main argument against the Crespi and Badcock theory is that many studies have shown that people with schizophrenia perform poorly on tests of social cognition (Couture et al., 2006, Sprong et al., 2007; Sparks et al., 2010;Lugnegård et al., submitted for publication). Furthermore, it is not uncommon that individuals with Asperger syndrome develop paranoid ideas due to misinterpretations and insecurity in social situa-tions (Wing, 1996, Blackshaw et al., 2001).

Psychiatric diagnoses are at present based on behaviour, behaviour that may be interpreted differently depending on the perspective and knowledge of the examiner. We need to regard the diagnostic classifica-tions as helpful instruments in order to recognise and treat psychiatric suffering, but always remember that they do not represent the defi ni-tive truth.

Funding

This work was supported by Värmland County Council, Wilhelm och Martina Lundgrens Vetenskapsfond II. The funding sources had no involvement in the study.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Irene Westlund, Magnus Segerström, Per-Nicklas Olofsson, Anna Göransson and Inga-Lill Sverkström for their help with WAIS-III assessment.

Appendix 1. Clinical vignettes

F1 Refered by school psychologist to the CAP at age 16 because of depression. Found personal relationships difficult, few friends, no close friends since age 11. Did not want to look people in the eyes, found it difficult to understand their behaviour. Preferred intellectual dialogues to social small talk. The depression was treated successfully with medication and supportive therapy. Contact ended after 7 months. First psychosis at age 23. - Schizophrenia paranoid subtype according to SCID, DISCO algorithm diagnosis autism with atypical age of onset and symptomatology.

F2 Contact with CAP at age 14 and 16. Psychiatric problems de-scribed were: Obsessions and compulsions, anxiety, self-injurious be-haviour, sleep problems, schoool refusal and conflicts in the family. Described as being hyperactive during early childhood. First psycho-sis at age 21. - Schizophrenia paranoid subtype according to SCID, DISCO algorithm diagnosis Asperger syndrome ICD-10.

F4 Referred for neurodevelopmental examination at age 12. Hy-peractive with verbal and motor tics. Teacher described some difficul-ties in relation to classmates, did not know how to relate to them, controlling, made naïve comments. Diagnosed with Tourette syn-drome and ADHD. First psychosis at age 20. - Schizophrenia undiffer-entiated subtype according to SCID. DISCO algorithm diagnosis was autism with atypical age of onset and symptomatology.

F5 Mother contacted CAP on behalf of her 17-year-old daughter. The daughter had, after moving for studies to a nearby town, estab-lished relationships with delinquent teenagers. Few friends during childhood and was therefore pleased finally finding friends but were drawn to alcohol and drug use and was badly beaten in a dis-pute. Parents and the social services decided she should move back home. She was offered therapy but refused. The situation resolved and contact ended after 2 months. First psychosis at age 22. - Schi-zoaffective disorder according to SCID. DISCO algorithm diagnosis au-tism with atypical age of onset and symptomatology.

F6 Contact with CAP acute at age 15. Depressed, signs of psychosis. In-patient treatment for 3 years for schizophrenia. Described as al-ways odd, difficulty making friends, school problems. Schizoaffective disorder according to SCID. Parents did not participate in an interview.

F7 Contact with CAP at age 17 because of self-injurious behaviour, anxiety and phobia. Difficulties in relation to classmates, had been bullied. School problems. First psychosis at age 18. - Schizoaffective disorder according to SCID. Parents did not participate in an interview. F8 Referred to CAP at age 17. Compulsions, obsessed with her ap-pearance, few friends, very demanding. Attended clinic only once. Re-fused further contact. Parents came three times. First psychosis at age 25. - Schizophrenia paranoid subtype according to SCID. Parents ac-tively declined participation.

M2 Contact with CAP at age 9 because of depression. Always avoided other children, anxious in new situation and with change. Preferred to stay at home, temper tantrums. First psychosis at age 22. - Schizophrenia paranoid subtype according to SCID. DISCO algo-rithm diagnosis Asperger syndrome ICD-10.

M5 Mother contacted CAP because her 16-year-old son was de-pressed. Was ambitious in school until the last year when he started to fail. Brooding about his appearance, avoided crowds. Alcohol and drug misuse. First psychosis at age 20. - Schizophrenia undifferen-tiated subtype according to SCID. DISCO algorithm diagnosis Asperger syndrome (Gillberg criteria).

M6 Referred acutely to CAP because of confusion at age 15. In-patient treatment several times due to psychosis. Delayed language development, later a correct somewhat pedantic speech. Major diffi -culties in relation to peers during childhood. Intelligent and had great knowledge in certainfields. - Schizoaffective disorder according to SCID. DISCO algorithm diagnoses autism and Asperger syndrome (Gillberg criteria).

M9 Referred for a neuropdevelopmental examination at age 16. Other family members have Asperger syndrome, and the patient was concerned about having the same diagnosis. The patient had some personality traits in the broader phenotype but did not meet criteria for diagnosis. First psychosis at age 21. - Bipolar I according to SCID. No ASD according to DISCO algorithm.

References

American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition (text revision (DSM-IV-TR)). APA, Washington, DC. Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D., Charman, T.,

2006. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). The Lan-cet 368, 210–215.

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., Clubley, E., 2001. The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning au-tism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and De-velopmental Disorders 31, 5–17.

Bastiaansen, J.A., Meffert, H., Hein, S., Huizinga, P., Ketelaars, C., Pijnenborg, M., Bartels, A., Minderaa, R., Keysers, C., de Bildt, A., 2011. Diagnosing autism spectrum disor-ders in adults: the use of Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) Module 4. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 41, 1256–1266.

Bearden, C.E., Rosso, I.M., Hollister, J.M., Sanchez, L.E., Hadley, T., Cannon, T.D., 2000. A prospective cohort study of childhood behavioral deviance and language abnor-malities as predictors of adult schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26, 395–410. Blackshaw, A.J., Kinderman, P., Hare, D.J., Hatton, C., 2001. Theory of mind, causal

attri-bution and paranoia in Asperger syndrome. Autism 5 (2), 147–163.

Cheung, C., Yu, K., Fung, G., Leung, M., Wong, C., Li, Q., Sham, P., Chua, S., McAlonan, G., 2010. Autistic disorders and schizophrenia: related or remote? An anatomical like-lihood estimation. PloS One 5, e12233.

Couture, S.M., Penn, D.L., Roberts, D.L., 2006. The functional significance of social cogni-tion in schizophrenia: A review. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32 (Suppl1), S44–S63. Craddock, N., Owen, M.J., 2010. The Kraepelinian dichotomy—going, going…but still

not gone. The British Journal of Psychiatry 196, 92–95.

Crespi, B., Badcock, C., 2008. Psychosis and autism as diametrical disorders of the social brain. Behavioral and Brain Science 31, 241–261.

Done, D.J., Crow, T.J., Johnstone, E.C., Sacker, A., 1994. Childhood antecedents of schizo-phrenia and affective illness: social adjustment at ages 7 and 11. BMJ 309, 699–703. Ehlers, S., Gillberg, C., 1993. The epidemiology of Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry 34, 1327–1350.

Eisenberg, L., Kanner, L., 1956. Childhood Schizophrenia Symposium 1955, Early infan-tile autism 1943–55. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 26, 556–566. Erlenmeyer-Kimling, L., Cornblatt, B.A., 1987. The New York High-risk Project: a

followup report. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13, 451–461.

Erlenmeyer-Kimling, L., Rock, D., Roberts, S.A., Janal, M., Kestenbaum, C., Cornblatt, B., Adamo, U.H., Gottesman, I., 2000. Attention, memory, and motor skills as child-hood predictors of schizophrenia-related psychoses: the New York High-Risk Pro-ject. The American Journal of Psychiatry 157, 1416–1422.

First, M.B., Gibbon, M., 2004. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disor-ders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II DisorDisor-ders (SCID-II). In: Hilsenroth, M.J., Segal, D.L. (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Psy-chological Assessment.: Personality Assessment, Vol. 2. John Wiley & Sons Inc, Ho-boken, NJ (US).

Fombonne, E., Quirke, S., Hagen, A., 2009. Prevalence and interpretation of recent trends in rates of pervasive developmental disorders. McGill Journal of Medicine 12, 73. Ghaziuddin, M., 2005. A family history study of Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders 35, 177–182.

Gillberg, C., 1992. The Emanuel Miller Memorial Lecture 1991. Autism and autistic-like conditions: subclasses among disorders of empathy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 33, 813–842.

Gillberg, I.C., Gillberg, C., 1989. Asperger syndrome–some epidemiological consider-ations: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 30, 631–638. Gotham, K., Pickles, A., Lord, C., 2009. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of

se-verity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disor-ders 39, 693–705.

Hjärthag, F., Helldin, L., Karilampi, U., Norlander, T., 2010. Illness-related components for the family burden of relatives to patients with psychotic illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 45, 275–283.

ISC, 2008. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature 455, 237–241.

Jones, P., Rodgers, B., Murray, R., Marmot, M., 1994. Child development risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. The Lancet 344, 1398–1402. Leask, S.J., Done, D.J., Crow, T.J., 2002. Adult psychosis, common childhood infections

and neurological soft signs in a national birth cohort. The British Journal of Psychiatry 181, 387–392.

Leekam, S.R., Libby, S.J., Wing, L., Gould, J., Taylor, C., 2002. The diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders: algorithms for ICD-10 childhood autism and Wing and Gould autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43 (3), 327–342.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., 1994. Autism diagnostic interview-revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive de-velopmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Dede-velopmental Disorders 24 (5), 659–685.

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook Jr., E.H., Leventhal, B.L., DiLavore, P.C., Pickles, A., Rutter, M., 2000. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of au-tism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 30, 205–223.

Lowyck, B., De Hert, M., Peeters, E., Wampers, M., Gilis, P., Peuskens, J., 2004. A study of the family burden of 150 family members of schizophrenic patients. European Psy-chiatry 19, 395–401.

McCarthy, S.E., Makarov, V., Kirov, G., Addington, A.M., McClellan, J., Yoon, S., Perkins, D.O., Dickel, D.E., Kusenda, M., Krastoshevsky, O., Krause, V., Kumar, R.A., Grozeva, D., Malhotra, D., Walsh, T., Zackai, E.H., Kaplan, P., Ganesh, J., Krantz, I.D., Spinner, N.B., Roccanova, P., Bhandari, A., Pavon, K., Lakshmi, B., Leotta, A., Kendall, J., Lee, Y.H., Vacic, V., Gary, S., Iakoucheva, L.M., Crow, T.J., Christian, S.L., Lieberman, J.A., Stroup, T.S., Lehtimaki, T., Puura, K., Haldeman-Englert, C., Pearl, J., Goodell, M., Willour, V.L., Derosse, P., Steele, J., Kassem, L., Wolff, J., Chitkara, N., McMahon, F.J., Malhotra, A.K., Potash, J.B., Schulze, T.G., Nothen, M.M., Cichon, S., Rietschel, M., Leibenluft, E., Kustanovich, V., Lajonchere, C.M., Sutcliffe, J.S., Skuse, D., Gill, M., Gallagher, L., Mendell, N.R., Craddock, N., Owen, M.J., O'Donovan, M.C., Shaikh, T.H., Susser, E., Delisi, L.E., Sullivan, P.F., Deutsch, C.K., Rapoport, J., Levy, D.L., King, M.C., Sebat, J., 2009. Microduplications of 16p11.2 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature Genet-ics 41, 1223–1227.

Mednick, S.A., Parnas, J., Schulsinger, F., 1987. The Copenhagen High-risk Project, 1962–86. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13, 485–495.

Mouridsen, S.E., Rich, B., Isager, T., 2008. Psychiatric disorders in adults diagnosed as children with atypi-cal autism. A case control study. Journal of Neural Transmis-sion 115, 135–138.

Niemi, L.T., Suvisaari, J.M., Tuulio-Henriksson, A., Lonnqvist, J.K., 2003. Childhood de-velopmental abnormalities in schizophrenia: evidence from high-risk studies. Schizophrenia Research 60, 239–258.

Nygren, G., Hagberg, B., Billstedt, E., Skoglund, Å., Gillberg, C., Johansson, M., 2009. The Swedish Version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disor-ders (DISCO-10). Psychometric properties. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (5), 730–741.

Nylander, L., Lugnegård, T., Unenge Hallerbäck, M., 2008. Autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adults–is there a connection? A literature review and some suggestions for future clinical research. Clinical Neuropsychiatry 5, 43–54. Owen, M.J., O'Donovan, M.C., Thapar, A., Craddock, N., 2011. Neurodevelopmental

hy-pothesis of schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry 198, 173–175. Rapoport, J., Chavez, A., Greenstein, D., Addington, A., Gogtay, N., 2009. Autism

spec-trum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: Clinical and biological contri-butions to a relation revisited. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48, 10–18.

Roy, M., Balaratnasingam, S., 2010. Missed diagnosis of autism in an Australian Indige-nous psychiatric population. Australasian Psychiatry 18, 534–537.

Schiffman, J., Walker, E., Ekstrom, M., Schulsinger, F., Sorensen, H., Mednick, S., 2004. Childhood videotaped social and neuromotor precursors of schizophrenia: a pro-spective investigation. The American Journal of Psychiatry 161, 2021–2027. Sparks, A., McDonald, S., Lino, B., O'Donnell, M., Green, M., 2010. Social cognition, empathy

and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 122, 172–178. Sporn, A.L., Addington, A.M., Gogtay, N., Ordonez, A.E., Gornick, M., Clasen, L.,

Greenstein, D., Tossell, J.W., Gochman, P., Lenane, M., Sharp, W.S., Straub, R.E., Rapoport, J.L., 2004. Pervasive developmental disorder and childhood-onset schizophrenia: comorbid disorder or a phenotypic variant of a very early onset ill-ness? Biological Psychiatry 55, 989–994.

Sprong, M., Schothorst, P., Vos, E., Hox, J., Van Engeland, H., 2007. Theory of mind in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry 191, 5–13. Toal, F., Bloemen, O.J.N., Deeley, Q., Tunstall, N., Daly, E.M., Page, L., Brammer, M.J.,

Murphy, K.C., Murphy, D.G.M., 2009. Psychosis and autism: magnetic resonance imaging study of brain anatomy. British Journal of Psychiatry 194, 418–425. van Niekerk, M.E.H., Groen, W., Vissers, C.T.W.M., van Driel-de Jong, D., Kan, C.C., Oude

Voshaar, R.C., 2010. Diagnosing autism spectrum disorders in elderly people. Inter-national Psychogeriatrics 1, 1–11.

Voineskos, A.N., Lett, T.A., Lerch, J.P., Tiwari, A.K., Ameis, S.H., Rajji, T.K., Muller, D.J., Mulsant, B.H., Kennedy, J.L., 2011. Neurexin-1 and frontal lobe white matter: an overlapping intermediate phenotype for schizophrenia and autism spectrum dis-orders. PloS One e20982 (United States).

Walker, E.F., Grimes, K.E., Davis, D.M., Smith, A.J., 1993. Childhood precursors of schizophre-nia: Facial expressions of emotion. The American Journal of Psychiatry 150, 1654–1660. Walker, E.F., Savoie, T., Davis, D., 1994. Neuromotor precursors of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia Bulletin 20, 441–451.

Wechsler, D., 1997. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 3rd ed. Psycho-logical Corporation, San Antonio, TX.

Weintraub, S., 1987. Risk factors in schizophrenia: the Stony Brook High-risk Project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13, 439–450.

Wing, L., 1996. The Autistic Spectrum: A Guide for Parents and Professionals. St Edmundsbury Press, London.

Wing, L., Gould, J., 1979. Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnor-malities in children: epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Develop-mental Disorders 9, 11–29.

Wing, L., Leekam, S.R., Libby, S.J., Gould, J., Larcombe, M., 2002. The Diagnostic Inter-view for Social and Communication Disorders: background, inter-rater reliability and clinical use. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43, 307–325. Woodbury-Smith, M.R., Boyd, K., Szatmari, P., 2010. Autism spectrum disorders,

schizo-phrenia and diagnostic confusion. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 35 (5), 360. World Health Organization, 2004. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and

Related Health Problems : ICD-10, 2nd ed. WHO, Geneva.