http://pbi.sagepub.com

DOI: 10.1177/10983007070090030401 2007; 9; 159 Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions

Joel P. Hundert

Children With Disabilities: Generalization to New Intervention Targets

Training Classroom and Resource Preschool Teachers to Develop Inclusive Class Interventions for

http://pbi.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/9/3/159 The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

Hammill Institute on Disabilities

and

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions

Additional services and information for

http://pbi.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Email Alerts:

http://pbi.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Teachers to Develop Inclusive Class

Interventions for Children With Disabilities:

Generalization to New Intervention Targets

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions

Abstract: Four preschool supervisors were individually trained in a collaborative team ap-proach in which classroom and resource teachers together developed a plan to increase the peer interactions of the entire class, including children with disabilities. The purpose of the research was to assess the generalization of effects to a new program target (children’s on-task behavior during circle time) and over time (3 months). The experimental phases of baseline, supervisor training, and follow-up were introduced in a multiple-baseline design across four preschool classes, each containing 2 children with disabilities. Behaviors of teachers, 8 children with dis-abilities, and 8 comparison children were measured during daily 20-min training sessions (in-door play periods) and generalization sessions (circle time). Results indicated that following supervisor training, teachers increased their focus on groups of children that included children with disabilities in both training and generalization sessions. After supervisor training, children with disabilities and comparison children increased their peer interactions during training ses-sions and their on-task behavior during circle time. Changes in teachers’ and children’s behav-iors in both settings were maintained at the 3-month follow-up observation. Implications for teacher training and consultation are discussed.

Joel P. Hundert

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

159

There is no longer much debate about whether to include children with disabilities in general education settings. The major challenge is how to plan the involvement of children with disabilities so that they and their typically developing classmates benefit maximally from the arrangement. The placement of children with disabilities in close physical proximity to typically developing peers without associated interventions tends not to result in gains in the social ad-justment of the children with disabilities (Guralnick & Groom, 1988; Hundert, Mahoney, Mundy, & Vernon, 1998). Compared to typically developing peers, children with dis-abilities placed in general classroom environments tend to play by themselves or interact with an adult, engage in more immature forms of play, and be rated by peers as nonpreferred play partners (Koegel, Koegel, Frea, & Fredeen, 2001; McGrath, Bosch, Sullivan, & Fuqua, 2003; Pierce-Jordan & Lifter, 2005).

In addition to deficits in peer interactions, children with disabilities in inclusive classrooms have been found to show more frequent off-task behavior (Young, Simpson,

Myles, & Kamps, 1997), higher rates of disruptive behavior (Gadow, Devincent, Pomeroy, & Azizian, 2005; Reese, Rich-man, Belmont, & Morse, 2005), less developed academic skills (Simpson, de Boer-Ott, & Smith-Myles, 2003), and more difficulty following classroom routines (Bryan & Gast, 2000) than their classmates.

in-terventions to adapt classroom routines to accommodate the full range of needs of children in the class, including those with disabilities.

With few exceptions, teachers have not been trained to develop interventions for use in the inclusive setting to accommodate children with disabilities. Interventions tar-geting specific deficits of preschoolers with disabilities in inclusive settings tend to be developed by consultants or experimenters without close collaboration with those im-plementing the interventions and without teaching imple-menters how to develop interventions themselves (Hunt, Soto, Maier, Liboiron, & Bae, 2004).

Training teachers to adapt their class activities to ac-commodate the needs of children with disabilities in one programming area (e.g., increased peer interaction) has the potential to result in teachers’ applying that training to different programming areas for the same children. If that proves to be the case, training teachers to develop inclusive class interventions would be a cost-effective alternative to providing consultation and training for each child with disabilities and each intervention target individually.

In Hundert and Hopkins (1992), preschool supervi-sors trained pairs of classroom and resource teachers to adapt class plans to produce increased interactions among peers in the class, including children with disabilities. They found an increase in the peer interactions of children with disabilities and in the proportion of time that teachers spent interacting with groups that included children with disabilities. Changes in both child and teacher behaviors generalized from indoor play sessions to outdoor play ses-sions. In another intervention, three day care teachers re-ceived feedback from a “coach” on their teaching, followed by suggestions for improvement (Henderson, Gardner, Kaiser, & Riley, 1993). Based on these suggestions, teachers set goals for how they would improve their teaching. Coaching produced an increase in teachers’ use of effective teaching procedures and a corresponding increase in the social interactions of children with disabilities.

In the study by Peck, Killen, and Baumgart (1989), three preschool teachers received two individual sessions of nondirective consultation in which they viewed a video-tape or received a verbal review by a consultant of their interactions with children with disabilities. With guided questioning from the consultant, the teachers then gener-ated ideas for possible interventions for identified child objectives. The teachers evaluated the ideas, narrowed them down to one or two for implementation, and received positive feedback from the consultant. Following consulta-tion, there was an increase in teachers’ use of prompts and consequences and in children’s targeted behaviors, both in a training setting and a generalization setting.

These studies suggest that with instruction, feedback, and supervision, teachers of preschoolers with disabilities can improve their teaching practices in the classroom, help-ing to brhelp-ing about gains in child targeted performance. Yet

Kontos, Moore, and Giorgetti (1998) found that preschool teachers were significantly more likely to ignore children with, than without, disabilities in their classes. Similarly, Hundert, Mahoney, and Hopkins (1993) found that class-room teachers showed significantly less interaction with children with disabilities than did resource teachers in the same class.

Promising interventions for classroom teachers to as-sist children with disabilities in inclusive classrooms cannot require prohibitively high teacher effort (Kohler, Anthony, Steighner, & Hoyson, 2001) and need to be practical to implement within the typical organizational structure of general education classrooms (Polychronis, McDonnell, Johnson, & Jameson, 2004). Types of teaching tactics that are effective and practical and can be embedded within the instructional routines of inclusive classrooms would in-clude (a) tactics to structure the learning environment to elicit the targeted child behavior, such as peer groupings (Chandler, Fowler, & Lubeck, 1992; Laushey & Heflin, 2000) or the selection and placement of materials (Chand-ler, Fow(Chand-ler, & Lubeck, 1992; Kim et al., 2003); and (b) tac-tics to embed instructions within classroom routines, including correspondence training (Morrison, Sainato, Benchaaban, & Endo, 2002; Odom, McConnell, & McEvoy, 1992), constant time delay (Chiara, Schuster, Bell, & Wol-ery, 1995), prompting procedures (Tate, Thompson, & McKerchar, 2005), and group contingencies (McConnell, Sisson, Cort, & Strain, 1991). The increased use of these tactics would be expected to result in an increase in class-room teacher behaviors directed toward groups of children that include children with disabilities within the classroom. Hundert (1994) conducted an ecobehavioral analysis of the effects of teacher training delivered by supervisors on co-occurrences of teacher and child behaviors. He found that after teacher training there was a significant in-crease in the conditional probability of interactive play of children with disabilities when teacher behaviors were di-rected toward groups of children that included children with disabilities. Interventions that result in increased teacher prompting, instruction, or reinforcement directed toward children with disabilities within inclusive groups may be an important component of teacher training (Chandler, Lubeck, & Fowler, 1992; Tate, Thompson, & McKerchar, 2005).

The purpose of the present study was to examine whether, following training showing preschool classroom and resource teachers together how to develop an inter-vention with a specific focus on one interinter-vention target (peer interaction during play sessions), teachers would be able to apply the training to the development of a different intervention target (on-task behavior during circle time), for which no specific information was provided in train-ing. Maintenance of the effects of teacher training to a 3-month follow-up observation was also evaluated.

Method

PARTICIPANTS

Four teachers, 8 children with disabilities, and 8 compari-son children were drawn from four urban preschool cen-ters, each containing 40 to 60 children organized into classes of 14 to 18. Each preschool center was under the di-rection of a supervisor who was trained and experienced in early childhood education but had no specialized back-ground in planning for children with disabilities. Supervi-sors were responsible for the general operation of the preschools, including teachers’ programming for classes and individual children.

Four female classroom teachers had community col-lege diplomas in early childhood education and a mean of 17.8 years of teaching experience (range = 7–22 years). Each class was assigned a part-time resource teacher to fa-cilitate the inclusion of children with disabilities. Resource teachers were trained in early childhood education, with additional community college training in special educa-tion for children with disabilities. Resource teachers had a mean of 7.7 years of experience and worked at a center for a mean of 4.7 hr a day 3.8 days a week.

Resource teachers were responsible for developing In-dividualized Education Programs (IEPs) for children with disabilities, drawing on input from paraprofessionals or classroom teachers, but implementation of IEPs tended to rest with the paraprofessionals or classroom teachers. Sim-ilarly, resource teachers were not typically involved in the development or implementation of plans for an entire class.

All 8 children with disabilities in the four preschool classes participated in the study. No child with disabilities at any of the three preschools was excluded from the study. All 8 children with disabilities had difficulties in peer in-teraction and on-task behavior identified in their IEPs. The 5 boys and 3 girls were all identified as having a special need under Ontario guidelines. Class 1 contained 18 chil-dren ranging in age from 3.1 to 4.1 years. In that class Gary, age 3.1 years, and Linda, age 3.8 years, had each been diag-nosed with a moderate developmental delay. They had global delays in all areas of development, with particu-lar weaknesses in communication, social skills, and

pre-academic skills. Class 2 contained 15 children ranging in age from 3.3 to 4.1 years, including Ellen, age 3.4 years, who had been diagnosed with a communication disorder with a developmental delay, and Jennifer, age 3.4 years, who had been diagnosed with cerebral palsy and a moder-ate developmental delay. Both had significant delays in communication, social skills, and preacademic skills. Class 3 had 16 children ranging in age from 4.0 to 5.1 years, with Tom, age 4.1 years, and Sam, age 4.9 years, each diagnosed with a moderate developmental delay that included signif-icant delays in communication, social skills, and preacad-emic skills. Class 4 contained 14 children ranging in age from 4.1 to 5.8 years. In that class, Cam, age 5.5 years, had been diagnosed with autism, a behavior disorder, and a language delay, and Adrian, age 4.9 years, had been diag-nosed as having a language delay.

All of the children with disabilities were rated by classroom teachers as having few friends, difficulty staying on task during circle time, and problems following class-room routines. Subsequent observation of these children indicated that their interactions with peers during play pe-riods was about one half the level shown by typically de-veloping children in the same classes. Similarly, the level of on-task behavior shown by children with disabilities was substantially lower than that displayed by comparison children.

There were two purposes of involving comparison children in the study. The first was to determine if the in-clusive class plan developed by teachers would have a pos-itive effect on the behavior of typically developing children in the class. The second purpose was for the comparison children to serve as a benchmark for the behavior of the children with disabilities (Fox & McEvoy, 1993). Compar-ison children were selected by the classroom teachers at random from the typically developing children in the same class and matched for gender and age, plus or minus 3 months. The 5 boys and 3 girls who served as compari-son children ranged in age from 3.1 to 5.8 years, with a mean of 3.9 years. Written informed parental consent was obtained for the participation of all children.

SETTINGS

Daily 20-min observations of child and teacher behaviors were recorded during both indoor play sessions (training setting) and circle time sessions (generalization setting). Play sessions were selected because they tend to promote high rates of peer interaction (Honig & McCarron, 1988). Circle time was selected because it has been associated with low levels of task engagement for preschool children (Greenwood, Carta, Kamps, & Arreaga-Mayer, 1990).

class-rooms. During these sessions, children were seated on the floor and participated in such activities as music, story time, games, or calendar discussion. Children were ex-pected to watch, listen, and respond when asked.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

A concurrent multiple-baseline design across classrooms was used to examine changes in teacher and child behav-iors after the introduction of teacher training in the col-laborative development of an inclusive class intervention. During baseline, teacher and child behaviors were re-corded without the benefit of training. Following baseline, preschool supervisors trained resource and classroom teachers to develop a plan to increase the peer interactions of all children in a class, including the children with dis-abilities. Generalization of teacher training to children’s and teachers’ behaviors during circle time was monitored.

Baseline

After 3 days for participants to become accustomed to the presence of observers, coding of teacher and child behav-iors was conducted under natural conditions during daily play sessions and circle time. Teachers were unaware of what behaviors were being recorded. At the beginning of this condition, supervisors asked the teachers to improve the peer interactions and on-task behavior of the class, including the children with disabilities. Supervisors gave no direction to teachers about how to bring about these changes.

Teacher Training

After 16 to 24 days of baseline, classroom and resource teachers were trained as a team to develop interventions to increase the peer interactions of all children in the class, with particular focus on the children with disabilities. During an initial 45-min meeting, the supervisor gave each teacher a written manual (available from the author) that indicated how to adapt a class plan to accommodate the needs of children with disabilities. The specific interven-tions covered by the training included both tactics to arrange the environment to elicit the child target behavior and tactics to embed teacher instruction, prompting, and reinforcement within inclusive groups of children. The manual described intervention components associated with adapting class programming under the headings of organizational arrangement (e.g., arranging the groupings of children), curriculum and activities (e.g., play materials), and instructional behaviors (e.g., prompting, reinforce-ment). Specific examples of applying intervention compo-nents to increasing peer interactions (e.g., clear demarcation of play areas, use of “social” toys, use of peer initiation training) were included in the training. Teachers were also provided with a planning form that guided them to con-sider whether they had each of several identified

compo-nents of an effective inclusive class plan in place, and if not, to plan how to make adaptations to incorporate these components. Resulting inclusive class plans were expected to include measurable objectives and a description of meth-odology for direct measurement of program outcomes.

During a second 45-min meeting with supervisors, classroom and resource teacher teams presented their in-clusive class plans on the form provided (see Table 1) and received positive feedback from supervisors. Supervisors evaluated whether each of 18 criteria of the training con-tent were included in the play session plans developed by teacher pairs. Supervisors also commented on the com-pleteness of the plans and ensured that all components of the training that teachers received were considered in their plans. All teacher plans did show that the teacher pairs at-tended to all of the training components. Within 2 weeks of implementation of the teachers’ plans, supervisors ob-served the plans in the classrooms and commented on pos-itive aspects of the intervention during a third 45-min session. No additional information was provided on how to develop interventions, nor did supervisors comment on the plans developed for on-task behavior. The number and length of training sessions were the same for all teacher pairs. A summary of the class plans developed by teacher pairs is shown in Table 1.

Prior to training, there were no systematic plans in place in any of the classes to increase child–peer interac-tions or foster improvement in any other area. The plans developed by each teacher pair were submitted to a judge naive to the purpose of the research who rated the plans on each of 18 criteria representing the content of training. All plans for play sessions and circle time sessions were rated as meeting at least 17 of the 18 criteria.

Follow-Up

Three months after the end of teacher training, three fur-ther observations were conducted of teacher and child be-haviors during both play and circle time sessions. Teachers were asked to conduct their classroom routines and inter-act with children as usual.

SUPERVISOR PREPARATION

MEASUREMENT SYSTEM

Three trained coders recorded the behaviors of the class-room teachers, the children with disabilities, and the comparison children during play and circle time sessions. Observers were situated outside the immediate area of ac-tivity but close enough to observe and hear the interac-tions of teachers and children. Observers recorded a child’s or teacher’s behavior on a momentary time sampling basis using 10-s signals emitted by an audiotape via earphones. Observers then recorded the behaviors of another partici-pant 10 s later. To control for possible order effects, each participant was observed once a minute, with the sequence randomly determined each session.

Teacher Behaviors

Prior to the study, classroom teachers did not use many strategies to involve children with disabilities in class rou-tines outside of circle time sessions. Teacher behavior cate-gories were adopted from the teacher focus subcategory of the Eco-Behavioral System for Complex Assessments of Pre-school Environments (ESCAPE; Carta, Greenwood, & At-water, 1986). Classroom teacher behavior directed toward groups of children that included a child with disabilities was selected because that measure has been associated with increased peer interactions of children with disabilities in inclusive classrooms (Hundert, 1994) and was expected to reflect general changes in teacher behavior associated with

the teachers’ use of the specific tactics introduced in the teacher training. Definitions of teacher focus codes and interobserver reliability results are shown in Table 2.

Child Behaviors

Child social interaction codes, adopted from Odom and McEvoy (1988), are shown in Table 2, along with inter-observer reliability results. Of particular interest were changes in children’s interactive play (IP).

Coder Training

The coders were four paid research assistants who had completed, or were about to complete, undergraduate de-grees in the social sciences. They each received 12 hrs of training in the response definitions and the observation system. Training consisted of written instructions, model-ing, feedback, and practice observation using videotapes of a play session at a preschool class not participating in the study. Training continued with individual observers until each achieved 90% accuracy on a paper-and-pencil quiz similar to that described by Stanley and Greenwood (1981) and at least 80% agreement with the author on three con-secutive practice observations.

Reliability checks of observers’ coding were conducted on approximately one third of sessions. Here, a second observer simultaneously but independently observed the same individual as the first observer, using sound cues

Table 1. Programs Developed by Teachers to Promote Peer Interaction and Increase On-Task Behavior

Program Teacher 1 Teacher 2 Teacher 3 Teacher 4

Peer interaction

Planned the position of children in the circle Used signs to prompt

di-rect following Increased rotation of play

material

Increased teacher physi-cal and verbal prompts

Increased child attending

Used two small circles

Used mats indicating

Varied toys that are available

Rehearsed how to ask peer to play

Increased child attending

Changed order of activities

Table 2. Response Definitions and Interobserver Reliability for Teacher and Child Behavior Codes

Interobserver reliability: M (range)

Code Abbreviation Definition %

Teacher behavior codes

Individual child with (I+) 95.9

disabilities (67–100)

Individual child (I–) 100.0

without disabilities

Group with 1 or (G+) 96.2

more children (75–100)

with disabilities

Group without a (G–) 75.0

child with (0–100)

disabilities

Other teacher (OT) 100.0

No response (NR) 87.8

(0–100)

Child behavior codes

Training sessions

Isolated/ (IO) 81.0

occupied play (0–100)

Proximity play (PP) 95.0

(85–100)

Interactive play (IP) 93.0

(75–100)

Negative play (NP) 100.0

Teacher (TI) 89.8

interaction (75–100)

No play (No) 87.1

(40–100)

Generalization sessions

Disruptive (D) 84.9

behavior (67–100)

On-task (On) 98.4

(93–100)

Off-task (Off) 81.9

(40–100) Teacher was located within 3 m of 1 child with disabilities (who

may have been in a group or isolated), and her verbal or non-verbal behavior was directed exclusively toward that child.

Teacher was located within 3 m of 1 child without disabilities (who may have been in a group or isolated), and her verbal and nonverbal behavior was directed exclusively toward that child.

Teacher’s verbal or nonverbal behavior was directed to a group that included 1 or more children with disabilities (e.g., asking children to put away their toys).

Teacher’s verbal or nonverbal behavior was directed toward a group that did not include a child with disabilities (e.g., dis-tributing aprons to a group of children without disabilities who were about to play with water toys).

Teacher directed her behavior toward the other teacher.

Teacher made no observable response directed to another indi-vidual or group (e.g., looking at a child).

Child was engaged in a play activity (e.g., pushing a toy truck, coloring) but was more than 2 m away from any other child. Child was engaged in a play activity within 2 m of at least 1

other child but was not interacting either verbally or non-verbally with another child.

Child was engaged in a play activity within 2 m of at least 1 other child and was interacting with another child, either ver-bally (e.g., talking about a play activity) or nonverver-bally (e.g., allowing another child to take turns playing with a toy, listen-ing when another child was talklisten-ing specifically to him or her). Child exhibited an aggressive, hostile, or rejecting behavior—

verbal (e.g., yelling) or nonverbal (e.g., pushing, sticking out tongue, threatening to hit)—toward another child.

Child displayed a verbal (e.g., talking) or nonverbal (e.g., sitting on lap) behavior directed to a teacher or other adult in the classroom.

Child was not engaged in any play activity (e.g., watching other children).

from the first observer’s audiotape via earphones with a

Y-adapter. Reliability calculations were based on occur-rences only and consisted of the number of agreements plus the number of disagreements multiplied by 100. Mean reliability coefficients for teacher and child behavior codes are shown in Table 2.

Results

TEACHER BEHAVIORS

All four teachers increased the amount of time they fo-cused on inclusive groups of children from baseline to

teacher training and maintained those heightened levels 3 months later (see Figure 1). Mean levels of teacher be-havior directed toward inclusive groups (G+) in play ses-sions were low during baseline but increased more than sixfold after the introduction of teacher training (from 7.6% to 21.6% for Teacher 1, from 3.9% to 22.2% for Teacher 2, from 1.3% to 29.6% for Teacher 3, and from 0.5% to 13.2% for Teacher 4). Except for Teacher 1, there was very little overlap in the data points between baseline and teacher training phases. These enhanced levels of teacher G+ were maintained 3 months later, with teachers spending a mean of 28.2% of their time focused on inclu-sive groups of children during play sessions.

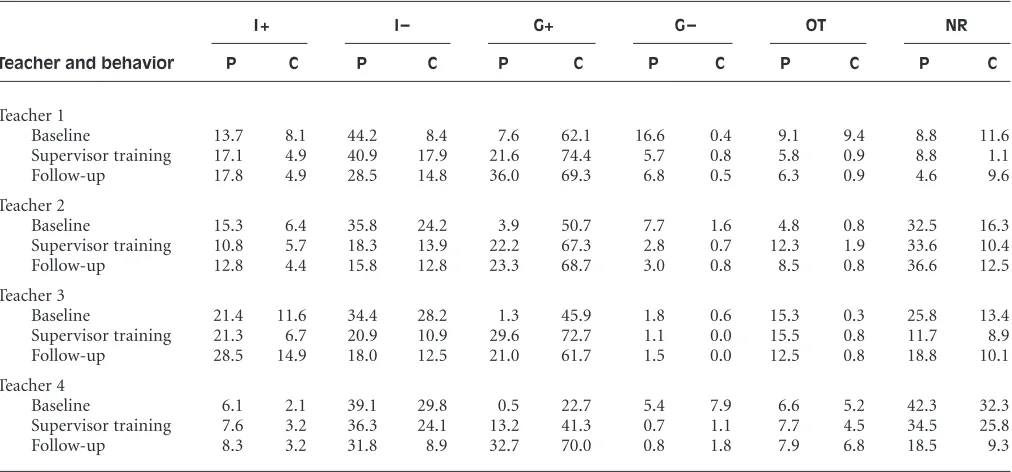

Similar, but more moderate, increases in teacher be-havior occurred during circle time sessions. As shown in Figure 1, baseline levels of teacher G+ during circle time sessions were higher than during play sessions, likely due to classroom teachers’ addressing comments to the entire group in circle. Table 3 shows the mean teacher behaviors during experimental phases. Each teacher showed an im-mediate increase in the mean amount of G+ after teacher training (from 62.1% during baseline to 74.4% during teacher training for Teacher 1, from 50.7% to 67.3% for Teacher 2, from 45.9% to 72.7% for Teacher 3, and from 22.7% to 41.3% for Teacher 4). Teacher 4 showed an in-creasing trend in G+ over the course of baseline, which ob-fuscates any further increase during teacher training. These increases in teacher G+ were maintained 3 months later, when means were 69.3% for Teacher 1, 68.7% for Teacher 2, 61.7% for Teacher 3, and 70.0% for Teacher 4. With some exceptions, a reduction in teacher focus on noninclusive groups (G−) and individual children without disabilities (I−) was associated with the increases in teacher G+. There was little or no change in teacher focus on indi-vidual children with disabilities (I+). Following training, teachers had more interactions with inclusive groups than with noninclusive groups and individual children without disabilities.

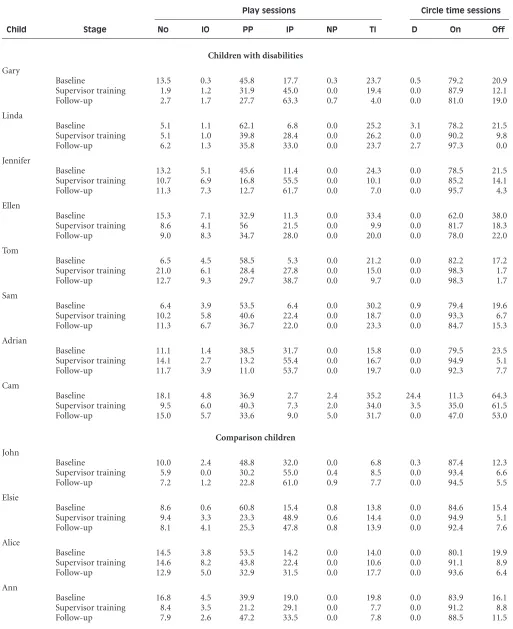

CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES

Figure 2 shows the percentage of interactive play for each child with disabilities during play sessions in the baseline,

teacher training, and follow-up phases. The results suggest that there was a slight increase in interactive play for some of the participants (Gary, Ellen, and Tom), no increase in interactive play for other participants (Jennifer, Sam, Adrian, and Cam), and unclear results for Linda. Levels of child IP, including any gains, were maintained during follow-up, with a mean of 33.8% across the 8 children.

Figure 3 represents the percentage of each child’s on-task behavior during circle time sessions and suggests that there was a slight to moderate increase in the on-task be-havior of children with disabilities after the introduction of teacher training. The mean percentage of on-task be-havior for the 8 children with disabilities increased from 68.8% during baseline to 83.3% during teacher training. Increased levels of children’s on-task behavior during cir-cle time sessions were maintained 3 months later, with a mean of 72.0%.

Means of children’s behaviors during play and circle time sessions for the children with disabilities are shown in Table 4. It can be seen that increases in IP during play ses-sions were associated with reductions in proximity play (PP) for all of the children with disabilities except Elaine, and with a decline in teacher interaction (TI) for Gary, Jennifer, Ellen, Tom, and Sam.

COMPARISON CHILDREN

Also shown in Table 4 are the results for the comparison children during the play and circle sessions. The occur-rence of IP in comparison children increased from a mean

Table 3. Mean Teacher Behavior Percentages in Play and Circle Time Sessions

I + I – G+ G – OT NR

Teacher and behavior P C P C P C P C P C P C

Teacher 1

Baseline 13.7 8.1 44.2 8.4 7.6 62.1 16.6 0.4 9.1 9.4 8.8 11.6

Supervisor training 17.1 4.9 40.9 17.9 21.6 74.4 5.7 0.8 5.8 0.9 8.8 1.1

Follow-up 17.8 4.9 28.5 14.8 36.0 69.3 6.8 0.5 6.3 0.9 4.6 9.6

Teacher 2

Baseline 15.3 6.4 35.8 24.2 3.9 50.7 7.7 1.6 4.8 0.8 32.5 16.3

Supervisor training 10.8 5.7 18.3 13.9 22.2 67.3 2.8 0.7 12.3 1.9 33.6 10.4

Follow-up 12.8 4.4 15.8 12.8 23.3 68.7 3.0 0.8 8.5 0.8 36.6 12.5

Teacher 3

Baseline 21.4 11.6 34.4 28.2 1.3 45.9 1.8 0.6 15.3 0.3 25.8 13.4

Supervisor training 21.3 6.7 20.9 10.9 29.6 72.7 1.1 0.0 15.5 0.8 11.7 8.9

Follow-up 28.5 14.9 18.0 12.5 21.0 61.7 1.5 0.0 12.5 0.8 18.8 10.1

Teacher 4

Baseline 6.1 2.1 39.1 29.8 0.5 22.7 5.4 7.9 6.6 5.2 42.3 32.3

Supervisor training 7.6 3.2 36.3 24.1 13.2 41.3 0.7 1.1 7.7 4.5 34.5 25.8

Follow-up 8.3 3.2 31.8 8.9 32.7 70.0 0.8 1.8 7.9 6.8 18.5 9.3

of 23.9% during baseline to a mean of 39.5% during teacher training, averaged across the 8 comparison chil-dren, and continued with a mean of 41.8% during follow-up. Increases in the children’s IP tended to be associated with a decline in PP for all comparison children except Ann (M= 49.6% during baseline to 38.6% during teacher training). It is interesting to note that the mean IP among the children with disabilities during teacher training (32.9%) approximated the mean IP among the comparison children during teacher training (38.6%) and was higher than the mean IP shown by the comparison children dur-ing baseline (23.9%).

The on-task behavior of the comparison children during the circle time tended to be high during baseline

(M= 82.0%) and increased further during teacher training (M= 92.5%), an increase that was maintained in follow-up (M= 91.8%).

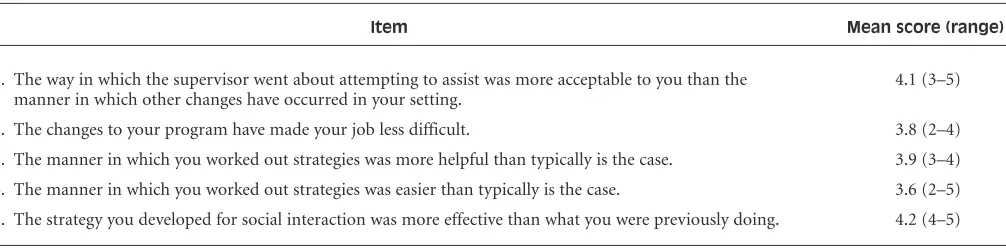

CONSUMER SATISFACTION

At the end of the study, resource and classroom teachers were asked to rate their satisfaction with the training. Teachers rated their agreement with statements about the acceptability of the intervention on a 5-point Likert scale. Results are shown in Table 5.

Teachers rated teacher training as acceptable, result-ing in more effective programs to promote social

tions; helpful; and making their job less difficult. Although still positive, teachers rated the ease of working out strate-gies lower than the other questions. Subsequent discus-sions with teachers during a debriefing suggested that although they found the intervention effective, it took a considerable amount of their time to plan and execute.

Discussion

This study found that after teacher training, teacher teams developed inclusive class interventions, and there was an

associated increase in teacher interactions with inclusive groups of children, mixed results for child target behaviors in the training situation (peer interaction in play sessions), and slight to moderate increases in child target behaviors in the generalization situation (on-task behavior during circle time). Any increases in teacher and child behaviors continued 3 months later. The intervention plans devel-oped by the teachers to address (a) peer interactions and (b) on-task behavior (see Table 1) were quite different from one another, but both were associated with increases in teacher behaviors directed toward inclusive groups of

Table 4. Mean Behavior Percentages of Children With Disabilities and Comparison Children

Play sessions Circle time sessions

Child Stage No IO PP IP NP TI D On Off

Children with disabilities

Gary

Baseline 13.5 0.3 45.8 17.7 0.3 23.7 0.5 79.2 20.9

Supervisor training 1.9 1.2 31.9 45.0 0.0 19.4 0.0 87.9 12.1

Follow-up 2.7 1.7 27.7 63.3 0.7 4.0 0.0 81.0 19.0

Linda

Baseline 5.1 1.1 62.1 6.8 0.0 25.2 3.1 78.2 21.5

Supervisor training 5.1 1.0 39.8 28.4 0.0 26.2 0.0 90.2 9.8

Follow-up 6.2 1.3 35.8 33.0 0.0 23.7 2.7 97.3 0.0

Jennifer

Baseline 13.2 5.1 45.6 11.4 0.0 24.3 0.0 78.5 21.5

Supervisor training 10.7 6.9 16.8 55.5 0.0 10.1 0.0 85.2 14.1

Follow-up 11.3 7.3 12.7 61.7 0.0 7.0 0.0 95.7 4.3

Ellen

Baseline 15.3 7.1 32.9 11.3 0.0 33.4 0.0 62.0 38.0

Supervisor training 8.6 4.1 56 21.5 0.0 9.9 0.0 81.7 18.3

Follow-up 9.0 8.3 34.7 28.0 0.0 20.0 0.0 78.0 22.0

Tom

Baseline 6.5 4.5 58.5 5.3 0.0 21.2 0.0 82.2 17.2

Supervisor training 21.0 6.1 28.4 27.8 0.0 15.0 0.0 98.3 1.7

Follow-up 12.7 9.3 29.7 38.7 0.0 9.7 0.0 98.3 1.7

Sam

Baseline 6.4 3.9 53.5 6.4 0.0 30.2 0.9 79.4 19.6

Supervisor training 10.2 5.8 40.6 22.4 0.0 18.7 0.0 93.3 6.7

Follow-up 11.3 6.7 36.7 22.0 0.0 23.3 0.0 84.7 15.3

Adrian

Baseline 11.1 1.4 38.5 31.7 0.0 15.8 0.0 79.5 23.5

Supervisor training 14.1 2.7 13.2 55.4 0.0 16.7 0.0 94.9 5.1

Follow-up 11.7 3.9 11.0 53.7 0.0 19.7 0.0 92.3 7.7

Cam

Baseline 18.1 4.8 36.9 2.7 2.4 35.2 24.4 11.3 64.3

Supervisor training 9.5 6.0 40.3 7.3 2.0 34.0 3.5 35.0 61.5

Follow-up 15.0 5.7 33.6 9.0 5.0 31.7 0.0 47.0 53.0

Comparison children

John

Baseline 10.0 2.4 48.8 32.0 0.0 6.8 0.3 87.4 12.3

Supervisor training 5.9 0.0 30.2 55.0 0.4 8.5 0.0 93.4 6.6

Follow-up 7.2 1.2 22.8 61.0 0.9 7.7 0.0 94.5 5.5

Elsie

Baseline 8.6 0.6 60.8 15.4 0.8 13.8 0.0 84.6 15.4

Supervisor training 9.4 3.3 23.3 48.9 0.6 14.4 0.0 94.9 5.1

Follow-up 8.1 4.1 25.3 47.8 0.8 13.9 0.0 92.4 7.6

Alice

Baseline 14.5 3.8 53.5 14.2 0.0 14.0 0.0 80.1 19.9

Supervisor training 14.6 8.2 43.8 22.4 0.0 10.6 0.0 91.1 8.9

Follow-up 12.9 5.0 32.9 31.5 0.0 17.7 0.0 93.6 6.4

Ann

Baseline 16.8 4.5 39.9 19.0 0.0 19.8 0.0 83.9 16.1

Supervisor training 8.4 3.5 21.2 29.1 0.0 7.7 0.0 91.2 8.8

Follow-up 7.9 2.6 47.2 33.5 0.0 7.8 0.0 88.5 11.5

children and an increase in targeted behavior among the children both with and without disabilities.

The increases in classroom teacher behaviors directed toward inclusive groups of children is likely a product of the teachers’ implementation of the interventions they de-veloped. Prior to the study, responsibility for objectives for children with disabilities would have fallen to resource teachers and paraprofessionals, who would have tended to design interventions for these children in isolation from class plans.

In the training delivered by supervisors, teachers were taught tactics for arranging environments to elicit child target behaviors and tactics to embed instruction, prompts, and feedback within classroom routines. With supervisor feedback, teacher teams then considered the content of training to modify their class plans. With the introduction

of the inclusive class plans, there was an increase in the amount of teacher behavior (instruction, prompts, and re-inforcement) directed toward inclusive groups of children. There was a reduction in teacher focus on individual children without disabilities and noninclusive groups of children, and no change in teacher interactions with indi-vidual children with disabilities. Associated with increased teacher interactions with inclusive groups was a mixed in-crease in child–peer interactions during play sessions and a slight to moderate increase in child attending during cir-cle time sessions. This study suggests that teachers can learn strategies previously found to be effective in inclusive classrooms through training delivered by their supervisors. This study replicates that of Hundert and Hopkins (1992), which found that teacher training to develop in-clusive class interventions increased child and teacher be-(Table 4 continued)

Play sessions Circle time sessions

Child Stage No IO PP IP NP TI D On Off

Bradley

Baseline 5.4 7.5 78.0 23.9 0.0 15.2 0.0 83.4 13.6

Supervisor training 11.1 0.0 40.8 41.8 0.0 6.4 0.0 93.3 6.7

Follow-up 9.3 3.3 31.8 43.5 0.0 12.1 0.0 90.1 19.9

Mike

Baseline 10.3 1.3 54.6 22.8 0.4 10.4 0.4 83.2 16.3

Supervisor training 6.4 0.0 52.9 37.4 0.0 3.3 0.0 95.0 5.0

Follow-up 8.2 1.0 48.8 29.7 0.8 11.5 0.6 91.1 8.9

Tom

Baseline 6.3 1.1 47.2 34.9 0.0 10.5 0.0 75.1 24.9

Supervisor training 9.3 0.7 36.4 43.6 0.0 10.0 0.0 87.4 12.6

Follow-up 11.2 0.7 29.7 48.9 0.0 9.5 0.0 89.1 10.9

Sam

Baseline 9.8 3.6 44.9 29.2 0.0 12.6 0.0 78.9 21.2

Supervisor training 8.7 2.2 33.2 31.5 0.0 21.0 0.0 93.8 8.2

Follow-up 6.0 4.5 29.5 38.1 0.0 21.9 0.0 95.6 4.4

Note. No = no play; IO = isolated or occupied play; PP = proximity play; IP = interactive play; NP = negative play; TI = teacher interaction; D = disruptive behavior; On = on-task behavior; Off = off-task behavior.

Table 5. Mean Responses to Items on the Teacher Feedback Questionnaire

Item Mean score (range)

1. The way in which the supervisor went about attempting to assist was more acceptable to you than the 4.1 (3–5) manner in which other changes have occurred in your setting.

2. The changes to your program have made your job less difficult. 3.8 (2–4)

3. The manner in which you worked out strategies was more helpful than typically is the case. 3.9 (3–4)

4. The manner in which you worked out strategies was easier than typically is the case. 3.6 (2–5)

5. The strategy you developed for social interaction was more effective than what you were previously doing. 4.2 (4–5)

haviors during indoor play sessions and generalized to in-creases in the same behaviors during outdoor play. The current study adds to the knowledge about teacher train-ing by findtrain-ing that followtrain-ing traintrain-ing to develop inclusive class interventions, teachers applied the training to the development of interventions for a different child target, with associated increases in teacher and child behaviors. It also illustrates a collaborative planning approach in which general and special education teachers together developed class plans to address targeted outcomes for all children in the class, including children with disabilities.

The current study differs in at least two ways from previous studies in which training or consultation was provided to teachers to help them develop interventions for children with disabilities (Henderson et al., 1993; Peck et al., 1989). First, the teachers were teamed and followed a general collaborative process through which they designed their own interventions, rather than being coached indi-vidually. Odom et al. (2004) have identified a collaborative planning process as an important component of the inclu-sion of children with disabilities, especially when the roles of the classroom and resource teachers are unclear.

A second difference is that teacher training was deliv-ered by the teachers’ supervisors, and supervisors’ active involvement in training may have been an important com-ponent in the obtained effects. Graden, Casey, and Bon-strom (1985) reported that one of the differences between schools that were and were not successful at implementing a prereferral intervention system was the visible support of administration. Similarly, there was little change following in-service instruction of residential staff in treatment pro-cedures for persons with mental retardation until supervi-sors were also trained in the procedure and how to instruct staff (Shore, Iwata, Vollmer, Lerman, & Zarcone, 1995). Teachers may be able to acquire programming skills, but their generalized application of those skills may depend upon supervisor actions that encourage and reinforce teacher efforts (Ingham & Greer, 1992). The level of behavior change found in the current study might not have been achieved had training been delivered by people other than the supervisors. The approach of using indigenous super-visors as trainers and encouraging a collaborative process for the development of interventions is consistent with the directions of positive behavior supports as described by Carr et al. (2002).

Training staff to develop their own interventions has a number of advantages over training staff to implement ready-designed programs. First, there is evidence of in-creased commitment to implementation when imple-menters are involved in the development of programs (Burgio, Whitman, & Reid, 1983; West & Idol, 1987; York & Vandercook, 1990). At a debriefing session held after the study, several teachers and supervisors commented that being involved in the design of the program made them

feel “proud of their accomplishments” and “confident in themselves.”

Second, helping teachers develop their own interven-tions allows them to fit the intervention to the needs of the particular children and routines of the setting. A process-oriented approach invites participants to tailor an inter-vention to fit their situations so that it is acceptable and feasible to implement. Moes and Frea (2000) found that a prescriptive treatment program for a child with autism that was not developed in collaboration with the family and was not sensitive to family routines produced little im-provement in the child’s challenging behaviors and com-pliance. In contrast, a treatment plan developed with the family was effective in reducing the child’s challenging be-haviors and in improving compliance.

A third advantage of the teacher training is that it may be a low-cost way to deliver service. In most preschool set-tings, it is simply not feasible to have a consultant design a program for each identified need of each child with dis-abilities and train teachers in its implementation. In the present study, teacher training took approximately 2 hrs to conduct for each supervisor. Even greater efficiency for consultants may be achieved by training supervisors as a group or using a pyramid training strategy (Neef, 1995).

There are several limitations to this study. Although there was a check on the fidelity of teacher training imple-mented by supervisors and on whether interventions devel-oped by teacher teams met the criteria established during training, there was no direct measure of whether teachers implemented their plans as designed. Without information on the consistency between planned and implemented teacher activities, it is difficult to attribute changes in teacher and child behaviors to the developed interventions. A second limitation is the lack of demonstration of which components associated with teacher training were responsible for the obtained effect on teacher and child be-haviors. The obtained effects of teacher training may not require all of the components that were introduced. A component analysis of teacher training in a collaborative team approach would help to identify which aspects of the procedure are critical and how to enhance the effect fur-ther.

teacher have a preexisting relationship. Training classroom and resource teachers as a team to develop inclusive class interventions, with supervisors providing the training, may hold promise as a strategy to foster effective, contex-tually sensitive, and collaborative supports for children with disabilities in general education settings.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joel P. Hundert, PhD, BCBA, is director of the Behaviour In-stitute, an agency serving children with autism, and an asso-ciate clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences at McMaster University. His cur-rent research interests include supported inclusion of children with disabilities, social skills interventions, and early in-tensive behavioral intervention. Address: Joel P. Hundert, Behaviour Institute, 57 Young Street, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, L8N 1V1; e-mail: hundert@mcmaster.ca

REFERENCES

Bryan, L. C., & Gast, D. L. (2000). Teaching on-task and on-schedule behav-iors to high-functioning children with autism via picture activity sched-ules.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30,553–567. Burgio, L. D., Whitman, T. L., & Reid, D. H. (1983). A participative

manage-ment approach for improving direct care staff performance in an institu-tional setting.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 16,37–53.

Carr, E. G., Dunlap, D., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., et al. (2002). Positive behavior supports: Evolution of an applied science.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4,4–16.

Carta, J. J., Greenwood, C. R., & Atwater, J. B. (1986).ESCAPE: Eco-behavioral system for complex assessments of preschool environments. Unpublished manual. Kansas City: University of Kansas, Bureau of Child Research, Ju-niper Gardens Children’s Project.

Chandler, L. K., Fowler, S. A., & Lubeck, R. C. (1992). An analysis of the ef-fects of multiple setting events on the social behavior of preschool chil-dren with special needs.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25,249–263. Chandler, L. K., Lubeck, R. C., & Fowler, S. A. (1992). Generalization and maintenance of preschool children’s social skills: A critical review and analysis.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25,415–428.

Chiara, L., Schuster, J. W., Bell, J. K., & Wolery, M. (1995). Small-group massed-trial and individually-distributed-trial instruction with pre-schoolers.Journal of Early Intervention, 19,203–217.

Fox, J. J., & McEvoy, M. A. (1993). Assessing and enhancing generalization and social validity of social skills interventions with children and adoles-cents.Behavior Modification, 17,339–366.

Gadow, K. D., Devincent, C. J., Pomeroy, J., & Azizian, A. (2005). Comparison of DSM-IV symptoms in elementary school-age children with PDD versus clinic and community samples.Autism, 9,392–415.

Graden, J. L., Casey, A., & Bonstrom, O. (1985). Implementing a prereferral intervention system: Part II. The data.Exceptional Children, 51,487–496. Green, C. W., Rollyson, J. H., Passante, S. C., & Reid, D. H. (2002).

Maintain-ing proficient supervisor performance with direct support personnel: An analysis of two management approaches. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35,205–208.

Greenwood, C. R., Carta, J. J., Kamps, D., & Arreaga-Mayer, C. (1990). Ecobe-havioral analysis of classroom instruction. In S. R. Schroeder (Ed.), Ecobe-havioral analysis and developmental disabilities (pp. 33–63). New York: Springer.

Grisham-Brown, J., Schuster, J., Hemmeter, M. J., & Collins, B. C. (2000). Using an embedding strategy to teach preschoolers with significant dis-abilities.Journal of Behavioral Education, 10,139–162.

Guralnick, M. J., & Groom, J. M. (1988). Peer interventions in mainstreamed and specialized classrooms: A comparative analysis.Exceptional Children, 54,415–435.

Henderson, J. M., Gardner, N., Kaiser, A., & Riley, A. (1993). Evaluation of a social interaction coaching program in an integrated day-care setting.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26,213–225.

Honig, A. S., & McCarron, P. A. (1988). Prosocial behaviors of handicapped and typical peers in an integrated preschool.Early Child Development and Care, 33,113–125.

Hundert, J. (1994). The ecobehavioral relationships between teachers’ and disabled preschoolers’ behaviors before and after supervisor training. Jour-nal of Behavioral Education, 4,77–93.

Hundert, J., & Hopkins, B. (1992). Training supervisors in a collaborative team approach to promote peer interaction of children with disabilities in integrated preschools.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25,385–400. Hundert, J., Mahoney, B., & Hopkins, B. (1993). The relationship between

re-source teacher and classroom teacher behaviors and the peer interaction of children with disabilities in integrated preschool.Topics in Early Child-hood Special Education, 13,328–343.

Hundert, J., Mahoney, B., Mundy, F., & Vernon, M. L. (1998). A descriptive analysis of developmental and social gains of children with severe disabil-ities in segregated and integrated preschools in Southern Ontario.Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13,49–65.

Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., Liboiron, N., & Bae, S. (2004). Collaborative teaming to support preschoolers with severe disabilities who are placed in general education early childhood programs.Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 24,123–142.

Ingham, P., & Greer, R. D. (1992). Changes in student and teacher responses in observed and generalized settings as a function of supervisor observa-tions.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25,153–164.

Kim, A., Vaughn, S., Elbaum, B., Tejero Hughes, M. T., Sloan, C. V., & Sridhar, D. (2003). Effects of toys or group composition for children with disabili-ties: A synthesis.Journal of Early Intervention, 25,189–205.

Koegel, L. K., Koegel, R. L., Frea, W. D., & Fredeen, R. M. (2001). Identifying early intervention targets for children with autism in inclusive school set-tings.Behavior Modification, 25,745–761.

Kohler, F., Anthony, L., Steighner, S. A., & Hoyson, M. (2001). Teaching social interaction skills in the integrated preschool: An examination of natural-istic tactics.Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 21,93–103. Kontos, S., Moore, D., & Giorgetti, K. (1998). The ecology of inclusion.

Top-ics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18,38–48.

Laushey, K. M., & Heflin, L. J. (2000). Enhancing social skills of kindergarten children with autism through the training of multiple peers as tutors. Jour-nal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 183–193.

McConnell, S. R., Sisson, L. A., Cort, C. A., & Strain, P. S. (1991). Effects of so-cial skills training and contingency management on reciprocal interaction of preschool children with behavioral handicaps.The Journal of Special Education, 24,473–495.

McGrath, A. M., Bosch, S., Sullivan, C. L., & Fuqua, W. (2003). Training re-ciprocal social interactions between preschoolers and a child with autism.

Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions, 5,47–54.

Moes, D. R., & Frea, W. D. (2000). Using family context to inform interven-tion planning for the treatment of a child with autism.Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2,40–46.

Morrison, R. S., Sainato, D. M., Benchaaban, D., & Endo, S. (2002). Increas-ing play skills of children with autism usIncreas-ing activity schedules and corre-spondence training.Journal of Early Intervention, 25,58–72.

Neef, N. A. (1995). Pyramid parent training by peers.Journal of Applied Be-havior Analysis, 28,333–337.

Odom, S. L., & McEvoy, M. A. (1988). Integration of young children with handicaps and normally developing children. In S. L. Odom & M. B. Karnes (Eds.),Early intervention for infants and children with handicaps(pp. 241– 268). Baltimore: Brookes.

Odom, S. L., Viztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., Hanson, M. J., et al. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective.Journal of Research in Special Education, 4,17–49.

Peck, C. A., Killen, C. C., & Baumgart, D. (1989). Increasing implementation of special education instruction in mainstream preschools: Direct and generalized effects of nondirective consultation.Journal of Applied Behav-ior Analysis, 22,197–210.

Pierce-Jordan, S., & Lifter, K. (2005). Interaction of social and play behaviors in preschoolers with and without pervasive developmental disorder. Top-ics in Early Childhood Special Education, 25,34–47.

Polychronis, S. C., McDonnell, J., Johnson, J. W., & Jameson, M. (2004). A comparison of two-trial distribution schedules in embedded instruction.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 190,140–151. Reese, R. M., Richman, D. M., Belmont, J. M., & Morse, P. (2005). Functional

characteristics of disruptive behavior in developmentally disabled children with and without autism.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35,416–428.

Sarokoff, R. A., & Sturmey, P. (2004). The effects of behavioral skills training on staff implementation of discrete-trial teaching.Journal of Applied Be-havior Analysis, 37,535–538.

Shore, B. A., Iwata, B. A., Vollmer, T. R., Lerman, D. C., & Zarcone, J. R. (1995). Pyramidal staff training in the extension of treatment for severe behavior disorders.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28,323–332. Simpson, R. L., de Boer-Ott, S. R., & Smith-Myles, B. (2003). Inclusion of

learners with autism spectrum disorders in general education settings.

Topics in Language Disorders, 23,116–133.

Stanley, S. O., & Greenwood, C. R. (1981).Code for instructional structure and student academic response (CISSAR): Observer’s manual. Kansas City: Uni-versity of Kansas, Bureau of Child Research, Juniper Gardens Children’s Project.

Tate, T. L., Thompson, R. H., & McKerchar, P. M. (2005). Training teachers in an infant classroom to use embedded teaching strategies.Education and Treatment of Children, 28,206–221.

West, J. F., & Idol, L. (1987). School consultation (part I): An interdisciplinary perspective on theory, models, and research.Journal of Learning Disabili-ties, 20,388–408.

York, J., & Vandercook, T. (1990). Strategies for achieving an integrated edu-cation for middle school students with severe disabilities.Remedial and Special Education, 11,6–16.

Young, B., Simpson, R. L., Myles, B. S., & Kamps, D. M. (1997). An examina-tion of paraprofessional involvement in supporting inclusion of students with autism.Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 12,

31–38.