The evaluation of a successful collaborative education model to expand

student clinical placements

Tony Barnett

a,*, Merylin Cross

a, Lina Shahwan-Akl

b, Elisabeth Jacob

a aSchool of Nursing and Midwifery, Monash University, Switchback Rd., Victoria, Australia 3842, Australia bDivision of Nursing and Midwifery, RMIT University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 3000, Australia

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Accepted 25 January 2009

Keywords: Clinical education Collaboration Preceptorship Student nurses

s u m m a r y

Worldwide, universities have been encouraged to increase the number of students enrolled in nursing courses as a way to bolster the domestic supply of graduates and address workforce shortages. This places pressure on clinical agencies to accommodate greater numbers of students for clinical experience who, in Australia, may often come from different educational institutions. The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate a collaborative model of clinical education that would increase the capacity of a health care agency to accommodate student placements and improve workplace readiness. The project was undertaken in a medium sized regional hospital in rural Australia where most nurses worked part time.

Through an iterative process, a new supported preceptorship model was developed by academics from three institutions and staff from the hospital. Focus group discussions and interviews were conducted with key stakeholders and clinical placement data analysed for the years 2004 (baseline) to 2007. The model was associated with a 58% increase in the number of students and a 45% increase in the number of student placement weeks over the four year period. Students reported positively on their experience and key stakeholders believed that the new model would better prepare students for the realities of nurs-ing work.

Ó2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The shortage of nurses in Australia and globally has been well documented (AHWAC, 2004; Buchan, 2005). Responses to this shortage have included; aggressive recruitment of nurses from other countries (Nelson, 2004; Ross et al., 2005), implementation of more effective workforce recruitment and retention strategies (VanOyen Force, 2005), introduction of new types or categories of health care worker, plus other changes to workforce composi-tion and skill mix (Duckett, 2004). Commentators have also sug-gested that the health care professions should critically examine the boundaries that restrict practices and constrain health care innovation and reform, and focus on developing a more flexible health care workforce (Malhotra, 2006).

A key strategy to build the nursing workforce is to increase domestic supply by: encouraging higher levels of participation from the existing workforce (i.e. reduce casualisation) and the re-entry of those who have left; reducing workforce separation rates; and increasing graduate numbers. Given that the ageing of the

nursing profession mitigates against many of these (Camerino et al., 2006) the single most effective and sustainable solution is to bolster the domestic supply of new graduates by increasing the number of students enrolled in nursing courses (Daly et al., in press).

An important component of nursing courses is that students undertake supervised and appropriately guided practice in a vari-ety of clinical settings (Murray et al., 2005). Whilst the amount of clinical is not uniformly mandated in Australia, all curricula leading to registration include a clinical component that typically increases as a student progresses through each year of the course. Any increase in student numbers will therefore impact on health care agencies, especially hospitals where much of this experience is gained. The ability of a clinical agency (‘‘hospital”) to accommo-date student nurses for clinical placement is a function of a number of factors including: bed capacity; occupancy; patient throughput; staffing profile, skill mix and workload; organisational culture and receptivity to students (Kilcullen, 2007). Cognisant of the burden students can place on staff, (Cowin and Jacobsson, 2003) further pressure to increase student numbers may make hospitals more reluctant to accept students for placement.

In order to graduate more nurses without contracting the time they spend in clinical settings as part of their education, new ways must be found to support clinical education without compromising

1471-5953/$ - see front matterÓ2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2009.01.018

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +61 3 99026636; fax: +61 3 99026527.

E-mail addresses: tony.barnett@med.monash.edu.au (T. Barnett),

merylin.-cross@med.monash.edu.au (M. Cross), lina.shahwan-akl@rmit.edu.au (L.

Shah-wan-Akl),Beth.Jacob@med.monash.edu.au(E. Jacob).

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Nurse Education in Practice

the standard of care provided by the hospital or the learning expe-rience of the student (Hall, 2006). Clinical education can be pro-vided through a number of mechanisms, though confusion exists over the nomenclature used to describe the person who provides this service (Cope et al., 2000; Hayes, 2005; Mills et al., 2005). In Australia, the term ‘‘preceptor” rather than ‘‘mentor”, is commonly used to describe a nurse who provides direct patient care and works one-to-one with a student during their placement.

This paper reports on a project in which more students were able to be placed for clinical experience in a hospital. The project involved collaboration between a rural hospital, two universities and an institute of Technical and Further Education (TAFE). The aim of the project was to develop, implement and evaluate a col-laborative model of clinical education that would increase the capacity of a hospital to accommodate student placements and im-prove students’ workplace readiness.

The problem of providing suitable clinical experience for stu-dents is not unique to this setting (Hall, 2006). This model could therefore be used by others to help increase the domestic supply of graduates and reduce reliance on other sources such as in-migration.

Background and setting

The setting for this study was a health service located in rural Victoria, Australia. Over the study period (2004/2007), the hospital offered a range of clinical services and had 83 acute in-patient and 90 aged care beds. In 2007, this agency employed around 300 reg-istered nurses. The majority (70%) of nurses were aged forty or over and 87% worked part time, a profile similar to the broader nursing workforce in rural Australia (AHWAC, 2004). Largely because of its rural location, this organisation had difficulties attracting and retaining nursing staff. It was keen to support more students for clinical placement with a view to recruiting some of them as new graduates (Courtney et al., 2002).

As with other public hospitals in the state, it did not have an exclusive student clinical placement arrangement with any one university. It received requests from a number of education provid-ers who competed to place students for periods of clinical experi-ence that ranged from a single day to six continuous weeks. Requests for clinical places were often for the same weeks of the year and as a consequence, the hospital experienced significant peaks and troughs in student numbers.

In the past, students placed with the hospital were normally supervised by a full-time clinical teacher on a 1:8 teacher: student ratio and allocated either singly or in small groups of 2–4 across a number of patient care areas (wards). Each education provider had its own administrative requirements and appointed and funded their own clinical teacher. Sometimes, the clinical teacher was sec-onded from the clinical area, though due to staff shortages it had been difficult for the hospital to release staff for this role. As others have found, lack of continuity, potential problems with entitle-ments, different expectations and working conditions, together with lack of familiarity with various curricula, clinical objectives, and clinical evaluation tools, made the role stressful, demanding and relatively unattractive (McKenna and Wellard, 2004).

Methods

A project group was formed that included senior staff from the hospital and representatives from the three major education pro-viders that placed students at the hospital. A participatory action approach was adopted (Street, 2004) that involved regular face to face and video-conference meetings and workshops which allowed the group to identify and explore solutions to barriers that limited

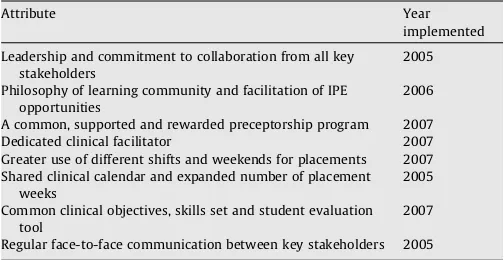

placement capacity (DHS, 2007). Through an iterative process and informed by a critical review of relevant literature (vide:Clare et al., 2003), a new model of clinical education was developed that addressed many of the problems identified. The model became the intervention for this study and had eight key attributes (Table 1).

Leadership and commitment to collaboration from all key stakeholders

The literature emphasises strong leadership, vision and a genu-ine commitment to work together as important to successful col-laboration (Griffiths and Crookes, 2006). With encouragement and support for the project from senior levels of participating organisations, a platform of shared governance (Moore and Hutch-ison, 2007) enabled stakeholders to freely discuss and respond to issues related to clinical education.

Philosophy of learning community and facilitation of Inter Professional Education (IPE) opportunities

The project team recognised that students, as adults, learn prac-tical knowledge in different ways and from a wide variety of peo-ple in addition to their clinical teacher or preceptor (Hall, 2006). The clinical environment was therefore conceptualised as a learn-ing community which comprised all staff who had some contact with students (Billett, 2004). In this way, it was planned that clini-cians would be engaged, empowered and recognised as an integral part of the educative process. To help promote positive inter pro-fessional relationships, a factor associated with job satisfaction and workforce retention, (VanOyen Force, 2005) the project team also planned expanded opportunities for students to participate in on-site education sessions taught by other disciplines (IPE).

A common supported and rewarded preceptorship program

Preceptorship has been widely used in nurse education though burnout is a common problem (Watson, 2000). Our goal was to en-sure clinical nurses who volunteered to act as preceptors were for-mally prepared and also supported in their teaching role (Magnusson et al., 2006). Each preceptor attended a workshop in which the background to the project was presented and topics such as: clinical education, the undergraduate curricula, prob-lem-solving, providing feedback and evaluating students were ad-dressed. A resource manual was developed for preceptors that included literature on clinical education, student learning activities and conflict resolution as well as a range of documentation associ-ated with student placements. Regular peer support meetings were scheduled for preceptors to de-brief and for their ongoing develop-ment. An overarching clinical facilitator position to support and develop preceptors was established at the hospital. Preceptors

Table 1

Key attributes and implementation of the model.

Attribute Year

implemented

Leadership and commitment to collaboration from all key stakeholders

2005

Philosophy of learning community and facilitation of IPE opportunities

2006

A common, supported and rewarded preceptorship program 2007 Dedicated clinical facilitator 2007 Greater use of different shifts and weekends for placements 2007 Shared clinical calendar and expanded number of placement

weeks

2005

Common clinical objectives, skills set and student evaluation tool

2007

were awarded certificates of recognition, CNE points, opportunities provided for honorary appointment to an education provider and credit toward formal post graduate studies. The resource efficien-cies generated by this model enabled some discretionary funds to be allocated to the clinical areas from which preceptors were drawn and students placed.

The project team estimated that around 40 preceptors would be needed. It was expected that these preceptors would maintain their patient case load though work closely with and be a role model for a student for the duration of their clinical placement block (from 1 to 4 weeks). The student would work the same shifts (including week ends) as the preceptor, thus be exposed to a range of experiences associated with nursing work.

Dedicated clinical facilitator

To provide continuity and consistency, a ‘clinical facilitator’ was appointed to manage the placement program and, as recom-mended by Watson (2000), to support ‘‘mentors”. The role in-cluded: supporting both preceptors and students, conducting preceptor training workshops and meetings, teaching and prob-lem-solving, assisting with student evaluations, organising rosters, facilitating student orientation and debriefs, rotating preceptors to prevent burnout, liaising with educators from the hospital and aca-demics from the education providers, and participating in research. A critical component of the role was to work with unit managers and engage other staff as part of the wider learning community. Funding for the position was apportioned across education provid-ers on the basis of student placement weeks.

Greater use of different shifts and weekends for placements

The project team was concerned to build clinical capacity in a way that exposed students to the realities of working life ( Magnus-son et al., 2006). The model allowed students to be placed with a preceptor across different shifts and at weekends, thereby spread-ing the student load over a greater period of time and in a larger number of patient care areas (wards). This reduced the saturation effect on patient care areas and increased opportunities for stu-dents to practice skills. The clinical facilitator was either present or on-call whenever students were at the hospital and both stu-dents and preceptors had access to the hospital educators and uni-versity staff as needed.

Shared clinical calendar and expanded number of placement weeks

A working group was formed to re-configure the student clini-cal placement timetables from each education provider. The group addressed areas of overlap, competition for placements, fragmen-tation and obvious peaks and troughs. Regular communication be-tween stakeholders provided an opportunity to examine, negotiate and make adjustments to increase the total number of weeks in the year that the hospital was able to accept students.

Common clinical objectives, skills set and student evaluation tool

Differences in curricula, clinical objectives, skill sets and stu-dent evaluation tools from the various education providers can cause confusion and create an additional burden on clinical staff and preceptors (Watson, 2000). The project team was committed to reducing the supervisory impost, simplifying the administrative workload and where possible eliminating ambiguity and differ-ence. Whilst some clinical objectives were unique to a course, sim-ilarities in clinical skills sets allowed the project team to consolidate these by year level for all students. Analysis of the range of clinical evaluation tools used by each educational provider

also identified many similarities as they were all based on national competency standards (http://www.anmc.org.au/). This feature al-lowed the project team to develop a simplified evaluation tool based on common skills sets and competencies.

Regular face-to-face communication between all key stakeholders

Communication, much of it face-to-face, inclusion and partici-pation were critical to: achieving a genuinely collaborative out-come, preparing preceptors for their role, resolving difficulties as they arose and providing support to all participants (Clare et al., 2003; Woods and Craig, 2005). Regular face-to-face meetings (up to 10 per year) were scheduled for the project group and aug-mented by video and teleconferencing to bridge the geographic distances between stakeholders.

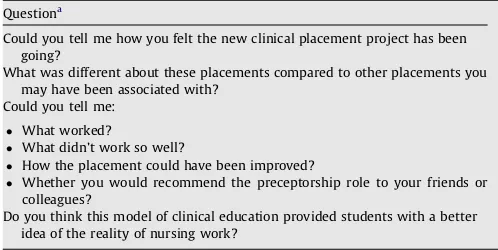

Procedures

Components of the model were phased in from 2005 and all ele-ments fully implemented during 2007 (Table 1). It was evaluated by the assessment of student placement metrics and feedback obtained from a survey (n= 79), focus group discussions (9 groups) and interviews (n= 5). Feedback was obtained from preceptors, students, education and management staff of the hospital during 2007. All discussions followed a semi-structured format (Table 2); were taped, transcribed and subjected to thematic and content analysis then verified with participants.

Students and preceptors were surveyed at the completion of a clinical placement block. The 26 items contained in the survey sought information about the: (a) adequacy of preparation for clin-ical, (b) learning environment and learning community, (c) value of shifts and weekends (d) ways to improve learning outcomes and (e) perceptions of work readiness. The information generated was presented to participants for discussion and recommendations incorporated for subsequent placements.

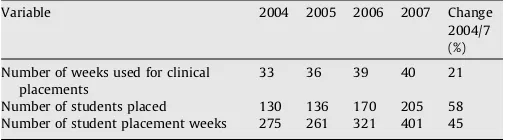

Student placement data for the years 2004 (baseline) to 2007 was collected to assess the impact on student placement metrics. The information gathered included: the total number of students placed at the hospital, the total number of weeks used for student placements, and the total number of student placement weeks. Student placement weeks represented the total number of weeks students had spent at the hospital. For example; three students, each placed for two weeks represented six student placement weeks (2 + 2 + 2 = 6).

Approval for the evaluative components of the project was ob-tained from the relevant institutional human ethics committee and from each participating institution.

Table 2

Preceptor focus group and interview questions.

Questiona

Could you tell me how you felt the new clinical placement project has been going?

What was different about these placements compared to other placements you may have been associated with?

Could you tell me:

What worked?

What didn’t work so well?

How the placement could have been improved?

Whether you would recommend the preceptorship role to your friends or

colleagues?

Do you think this model of clinical education provided students with a better idea of the reality of nursing work?

a

Results and discussion

Implementation of the model was associated with a major in-crease in the hospital’s capacity to accommodate student place-ments. Feedback received from key stakeholder groups was predominantly positive and students generally reported favour-ably on the quality of their learning experience.

Following a call to clinical nurses interested in participating as a preceptor with this new model, two preparatory one day work-shops were held to orientate preceptors to their new role. Of the 39 RNs who attended the workshops, 36 went on to preceptor students. In 2007, a total of 75 preceptors were needed, close to double that predicted. This was almost singularly due to the staffing profile of this agency; a very high proportion of part-time staff employed at a low fraction. The mismatch flags the need for more sophisticated planning when dealing with the con-temporary reality of a large part-time or casual workforce.

Students valued access to and working one-on-one with a preceptor: ‘‘I had the same preceptor so I followed her shifts. She was amazing; I did not want to leave her” though in reality, most students had 2–3 preceptors. When this was the case, one was designated the primary preceptor, the second a ‘‘secondary preceptor” and the third (and subsequent preceptors), as a ‘‘buddy”. Those who had three or four preceptors also felt the experience was rich and felt supported, ‘‘Even with different pre-ceptors it was still a rich experience.” Not surprisingly there was also feedback that too many preceptors compromised the place-ment experience ‘‘I had seven preceptors, some were helpful, some were not”.

How students perceive the clinical learning environment and re-late to preceptors is known to affect their learning (Mamchur and Myrick, 2003). A number of students commented on variation in style, skill and attitudes of preceptors. Some they found helpful and made them feel welcome, whereas others made them feel as if they were a burden or nuisance and had unrealistic expectations of them.

Most preceptors reported that they enjoyed the role though as noted byWatson (2000), the combination of maintaining a case-load in addition to the preceptor role is demanding. As one RN wrote:

I don’t believe that there are any negative points with this sys-tem, only positive aspects, and so far it has been exhausting for the preceptors but hopefully we will achieve an enhanced qual-ity of graduates to care for us in our advancing years. We reap what we sow.

Preceptors appreciated the support received from the clinical facilitator with this new model, particularly in monitoring their dual clinical/educative workload and need for respite from the role.

Have previously acted in the preceptor role; this placement model was different because the clinical facilitator was avail-able for support and visited the clinical areas regularly to check up on preceptors and students. This had not been the case with previous preceptoring experiences where there was no or very little backup.

Where possible, students worked the same roster as their des-ignated preceptor. Preceptors were almost unanimous that work-ing different shifts increased students’ work readiness. As one commented: ‘‘was more realistic than the clinical teaching model for practicum. Students are immersed in the real workplace.” Stu-dents also reported on the benefits; ‘‘working shifts teaches us about workload and time management.” Another explained, ‘‘showed what goes on in each shift. . .different skills in each

shift. . .so was good to get a mix.” Student and preceptor comments

on the value of weekend shifts were mixed. Most favoured the inclusion of late (pm) and early (am) shifts over the clinical place-ment period though were concerned that weekend shifts interfered with students’ need for paid employment.

Students perceived the majority of staff to be approachable and clinical units pleasant to work in. Their feedback suggested that the philosophy of learning community was central to a positive learn-ing environment, enriched their clinical experience and contrib-uted to their sense of belonging (Levett-Jones and Lathlean, 2008). Students appreciated learning from and interacting with other members of the health team and cited other nurses (RNs), followed by doctors, allied health workers and other students as important contributors to their clinical learning. They participated in 11 out of a possible 12 scheduled in-service IPE learning oppor-tunities. These sessions were attended by staff and students from other health disciplines and included topics such as: basic life sup-port, managing ‘‘difficult” patients, palliative care and wound care products. A further outcome of this project was that it provided an opportunity for the agency to collate the in-service learning ses-sions offered by different departments and advertise these more widely.

Some rationalisation of students’ clinical objectives was achieved across education providers. Of greater impact, were the introduction of a common ‘skills set’ list that allowed preceptors to quickly identify the intended skill capability of a student by their year level and a common clinical evaluation tool. Feedback from preceptors was overwhelmingly positive: ‘‘The standardised evalu-ation form was a noticeable improvement. Didn’t have to fill in reams of paper, it was a very practical form to use.”

Collaborations and partnerships can be resource and time con-suming (Clare et al., 2003). In this project, some participants had to travel considerable distances (up to 250 km) to attend face-to-face meetings. The ability of video and tele-conferencing to replace these meetings and defray travel costs was, unfortunately, limited by system incompatibilities and demand from other service users. The development of a shared clinical calendar increased the number of weeks in which the hospital could accept students for placements. In 2004, 33 weeks were utilised to place a total of 130 students. In 2007, 40 weeks were used and 205 students were able to be placed (Table 3). Student placements were better aligned and there were fewer (wasted) periods when no students were placed (Magnusson et al., 2006). With some minor adjustments to on-campus teaching schedules and the addition of several smal-ler specialist areas to the placement roster, more students were able to be accommodated more evenly, whilst ensuring that the venue was not saturated with students at any one time.

In addition to positive feedback from key stakeholders, the model was also associated with a major increase in placements. From 2004 to 2007, the number of students placed at the health service increased by 58% from 130 to 205 and the number of stu-dent placement weeks increased from 275 to 401 (45%). The poten-tial capacity to accommodate students was greater than these figures indicate as some planned placements did not eventuate. In 2004, the potential capacity of the hospital was to accommodate 317 student placement weeks and this increased to 455.4 weeks in

Table 3

Student placement metrics.

Variable 2004 2005 2006 2007 Change

2004/7 (%)

Number of weeks used for clinical placements

33 36 39 40 21

2007. The major reason for this capacity not being achieved was the cancellation (and non-replacement) of placements. The issue of cancellations does not feature in the clinical education literature but in this study, surfaced as a significant issue that can erode capacity and frustrate stakeholders (DHS, 2007).

Conclusion

In this project, a collaborative model of clinical education was developed that supported an increase in the capacity of a hospital to accept students for placement. Feedback suggested that as a consequence, workplace readiness was likely to be improved. Fea-tures of the model included: creation of a learning community, in-creased IPE opportunities, changes to the clinical timetable, development of a clinical preceptorship program supported by a full-time clinical facilitator and development of common; clinical objectives, skill sets and a clinical evaluation tool.

A limitation to this study was that it was conducted at one hos-pital with its own particular structure, culture and staffing profile. A workforce reality however, is that many nurses work part time. A challenge for the profession is to test models of preceptorship that can build the capacity of a hospital when there are fewer full time and more part-time RNs available to act as preceptors. Further evaluative studies are needed to assess how these changes may af-fect student learning and how best to reward and support precep-tors to ensure the role is valued and job satisfaction is maintained. The problem of providing sufficient, cost-effective quality clini-cal experiences for students and supporting their learning without unnecessary duress or burden on clinical agencies and their staff is not unique to this setting or to this country. Elements of this model could therefore be used or adapted by others to help increase the number of students entering health professional courses. The cur-rent shortage of nurses points to the importance of a continued supply of sufficient numbers of new graduates to sustain the health care system into the future. An increase in domestic supply of nurses could reduce reliance on in-migration as the solution to shortages in the longer term.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and students who participated in this project and the Department of Human Services (Victoria) who provided funding for the study.

References

AHWAC (Australian Health Workforce Advisory Committee), 2004. Nursing Workforce Planning in Australia, AHWAC Report 2004.1. Sydney.

Billett, S., 2004. Workplace participatory practices: conceptualising workplaces as learning environments. Journal of Workplace Learning 16 (6), 312–324. Buchan, J., 2005. Workforce statistics, global shortage in health care skills reaches

crisis point. Employing Nurses and Midwives.

Camerino, D., Conway, P.M., Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M., Estryn-Behar, M., Consonni, D., Gould, D., Hasselhorn, H-M., 2006. Low-perceived work ability, ageing and intention to leave nursing: a comparison among 10 European countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing 56 (5), 542–552.

Clare, J., Edwards, H., Brown, D., White, J., 2003. Evaluating Clinical Learning Environment: Creating Education-Practice Partnerships and Clinical Education Benchmarks for Nursing. Learning Outcomes and Curriculum Development in Major Disciplines: Nursing Phase 2 Final Report. Flinders University, Adelaide. Cope, P., Cuthbertson, P., Stoddart, B., 2000. Situated learning in the practice

placement. Nursing 31 (4), 850–856.

Courtney, M., Edwards, H., Smith, S., Finlayson, K., 2002. The impact of rural clinical placement on student nurses’ employment intentions. Collegian 9 (1), 12–18. Cowin, L., Jacobsson, D., 2003. Addressing Australia’s nursing shortage: is the gap

widening between workforce recommendations and the workplace? Collegian 10 (4), 20–24.

Daly, J., Clark, J.M., Lancaster, J., Bednash, G., Orchard, C., in press. The global alliance for nursing education and scholarship: delivering a vision for nursing education. International Journal of Nursing Studies.<www.elsevier.com/locate/ijnurstu>. doi:10.1016/j.injnurstu.2007.08.002.

DHS (Department of Human Services),, 2007. Clinical Placement Innovation Projects Report. Victorian Government Department of Human Services, Melbourne. Duckett, S.J., 2004. The Australian Health Care System, third ed. Oxford University

Press, Melbourne.

Griffiths, R., Crookes, P., 2006. Multidisciplinary teams. In: Daly, J., Speedy, S., Jackson, D. (Eds.), Contexts of Nursing, second ed. Churchill Livingstone, Sydney, pp. 184–198.

Hall, W.A., 2006. Developing clinical placements in times of scarcity. Nurse Education Today 26, 627–633.

Hayes, E., 2005. Approaches to mentoring: how to mentor and be mentored. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 17 (11), 442–445.

Kilcullen, N.M., 2007. Said another way: the impact of mentorship on clinical learning. Nursing Forum 42 (2), 95–104.

Levett-Jones, T., Lathlean, J., 2008. Belongingness: a prerequisite for nursing students’ clinical learning. Nurse Education in Practice 8, 103–111.

Magnusson, C., O’Driscoll, M., Smith, P., 2006. New roles to support practice learning – can they facilitate expansion of placement capacity? Nurse Education Today 27, 643–650.

Malhotra, G., 2006. Grow Your Own: Creating The Conditions For Sustainable Workforce Development. Kings Fund, London.

Mamchur, C., Myrick, F., 2003. Preceptorship and interpersonal conflict: a multidisciplinary study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 43 (2), 188–196. McKenna, L.G., Wellard, S.J., 2004. Discursive influences on clinical teaching in

Australian undergraduate nursing programs. Nurse Education Today 24 (3), 229–235.

Mills, J.E., Francis, K.L., Bonner, A., 2005. Mentoring, clinical supervision and preceptoring: clarifying the conceptual definitions for Australian rural nurses: a review of the literature. Rural and Remote Health 410, 1–10.

Moore, S.C., Hutchison, S.A., 2007. Developing leaders at every level; accountability and empowerment actualized through shared governance. Journal of Nursing Administration 37 (12), 564–568.

Murray, C., Borneuf, A.M., Vaughan, J., 2005. Working collaboratively towards practice placements. Nurse Education in Practice 5, 127–128.

Nelson, R., 2004. The nurse poachers. The Lancet 364, 1743–1744.

Ross, S.J., Polsky, D., Sochalski, J., 2005. Nursing shortages and international nurse migration. International Nursing Review 52, 253–262.

Street, A.F., 2004. Action research. In: Minichiello, V., Sullivan, G., Greenwood, K., Axford, R. (Eds.), Research Methods for Nursing and Health Science, second ed. Pearson Education, Frenchs Forest, pp. 278–294.

VanOyen Force, M., 2005. The relationship between effective nurse managers and nursing retention. Journal of Nursing Administration 35 (7/8), 336–341. Watson, S., 2000. The support that mentors receive in the clinical setting. Nurse

Education Today 20, 585–592.