STUDENT STRATEGY IN LEARNING VOCABULARY

A THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Magister Humaniora (M. Hum.)

in English Language Studies

By

Sutama 056332033

THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDY PROGRAM

GRADUATE SCHOOL

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

YOGYAKARTA

Dedicated to

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all I must express my greatest gratitude to God the Almighty who has guided and provided me with all His kindness. Without His blessing it would be impossible for me to finish this thesis. May He always be with us.

I would like to express my special gratitude to my respected lecturer and supervisor, Drs. F.X. Mukarto, M.S., Ph.D., who always advised and encouraged me to finish my study. His continuous encouragement inspired me to devote my struggle to complete this thesis.

I should also thank to my other invaluable lecturers; Dr. J. Bismoko who opened my mind with his fruitful lectures and progressive views on research particularly in English language education, Dr. BB. Dwijatmoko, M.A. for his interesting linguistic courses, Dr. Novita Dewi, M.S., M.A. (Hons) who taught me how to see the world through literary works, and Kuswandono M. Ed. who taught me how to make good scientific writing. Their valuable lectures during the course of my study encouraged me to be a better teacher.

Sutama, 2010. Student’s Strategy in Learning Vocabulary. Yogyakarta: English Language Study Program, Graduate School, Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta.

ABSTRACT

This study was designed to investigate student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary. It

investigated student‘s background experience, action, and intention in learning vocabulary.

The research question was: What is student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary? The goal of the research was to describe and identify student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary. More specifically, it aimed at reaching the subsequent objectives: (1) to describe student‘s background experience in learning vocabulary; (2) to describe student‘s actions in learning vocabulary and (3) to identify student‘s intentions in learning vocabulary.

The study adopted qualitative research design. The research setting was State Vocational High School 1 Kalasan (SMK Negeri 1 Kalasan) with two chosen student-participants involved. The research data was narrative. It was gathered through in-depth interviews with the two participants about their background experience, action, and intention in learning vocabulary. The data analysis was conducted by extracting the information from the data gathered through in-depth interviews. Then, the data was classified into categories and described in accordance with the research question.

The findings suggest that: (1) Student‘s background experience in learning, beliefs, affective states, and personality affect the choice of actions in vocabulary learning. (2) Various actions are taken to learn vocabulary depending on the stages of vocabulary learning; (a) the student discovers the meaning of new words by guessing from textual context, using bilingual dictionary, asking classmates, discovering through group work activity, and asking the teacher; (b) the student retains the word in long-term memory through written and verbal repetition, using new word in sentences, taking notes in class, doing English test items, using computer games, remembering affixes and roots, connecting the word to personal experience or interest, studying the sound of the word, and memorizing the word; (c) the student recalls the word by remembering its spelling, making use of note book, and relating the word with some previously learned knowledge; and (d) the student learns to use the word in spoken form by studying similar sounding words, using bilingual dictionary, asking teacher for the pronunciation of a word, saying new word aloud when studying, using English language media, and interacting with native-speaker; and learns to use the word in written form by studying the spelling of the word and using new words in sentences. (3) Student‘s intentions in learning vocabulary are to get better achievement, to pass the National Exam, to meet the demand of world of work, and to enter a university.

The study concludes that the student‘s background experiences underlie student‘s choice of action or strategy. The actions are taken based on student‘s background experiences dan student‘s beliefs and views on the efectiveness and appropriateness of the actions. It is important to provide the students with greater exposure to the variety of the strategy. In terms of classroom learning, the use of vocabulary learning strategy is also influenced by the classroom learning situation. Therefore, interesting vocabulary instruction is needed to reduce

Sutama, 2010. Student’s Strategy in Learning Vocabulary. Yogyakarta: Kajian Bahasa Inggris, Program Pasca Sarjana, Universitas Sanata Dharma, Yogyakarta.

ABSTRAK

Penelitian ini dimaksudkan untuk mengetahui strategi siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata. Lebih jelasnya untuk meneliti pengalaman, tindakan, dan maksud siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata. Pertanyaan penelitian ini dirumuskan sebagai berikut: Apa strategi siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata? Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk menggambarkan and mengenali strategi siswa untuk mempelajari kosakata. Lebih jelasnya penelitian ini bertujuan untuk: (1) menggambarkan pengalaman siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata, (2) menggambarkan langkah-langkah atau tindakan siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata, dan (3) mengidentifikasi maksud atau keinginan siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata.

Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian kualitatif. Tempat penelitian adalah SMK Negeri 1 Kalasan dengan menggunakan dua orang siswa sebagai peserta penelitian. Data penelitian bersifat naratif dan dikumpulkan melalui wawancara mendalam dengan kedua siswa tersebut tentang pengalaman siswa, langkah-langkah atau tindakan siswa, dan maksud atau keinginan siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata. Analisa data dilakukan dengan mengendapkan informasi yang diperoleh melalui wawancara mendalam, kemudian data dikategorikan, diuraikan berdasarkan kategori tersebut sesuai dengan pertanyaan penelitian.

Temuan penelitian menunjukkan bahwa: (1) pengalaman belajar, keyakinan, kondisi perasaan, dan kepribadian siswa mempengaruhi pilihan strategi dalam mempelajari kosakata. (2) berbagai tindakan dilakukan untuk mempelajari kosakata sesuai dengan tahapan belajar kosakata; (a) siswa menemukan makna kata baru dengan cara menebak dari konteksnya, menggunakan kamus dwi-bahasa, bertanya kepada teman, melalui kerja kelompok, dan bertanya kepada guru; (b) siswa menyimpan kosakata dalam ingatan dengan cara menulis dan mengucapkan kata tersebut secara berulang-ulang, menggunakan kata baru dalam kalimat, membuat catatan di kelas, mengerjakan soal-soal tes bahasa Inggris, menggunakan permainan dalam komputer, mengingat imbuhan dan kata dasar, menghubungkan kata baru dengan pengalaman atau kepentingan pribadi, mempelajari bunyi suatu kata, dan dengan mengingat-ingat kata tersebut; (c) siswa secara sadar mengmengingat-ingat kembali kosakata dengan cara mengmengingat-ingat ejaannya, membuka buku catatan, dan mengkaitkan kata tersebut dengan pelajaran atau pengetahuan yang telah dipelajari sebelumnya; dan (d) siswa belajar menggunakan kosakata secara lisan dengan cara mempelajari kata-kata yang berbunyi mirip, mengikuti cara membaca di dalam kamus, menanyakan pada guru tentang pengucapan suatu kata, mengucapkan dengan keras saat belajar, menggunakan media berbahasa Inggris, dan berinteraksi dengan penutur asli; dan belajar menggunakan kosakata secara tertulis dengan cara mempelajari ejaan suatu kata serta menggunakannya di dalam kalimat. (3) maksud atau keinginan siswa dalam mempelajari kosakata adalah untuk memperoleh prestasi yang lebih baik, untuk lulus dalam ujian nasional, untuk memenuhi permintaan dunia kerja, dan untuk mempersiapkan diri memasuki perguruan tinggi.

TABLES OF CONTENTS

3. Relevant Research on L2 Vocabulary Learning and Acquisition ………. .. 6

B. Problem Identification ……… ... 9

e. Receptive vs. Productive Knowledge of Vocabulary ……….. ... 27

2. Vocabulary Learning ……… 29

a. Some Aspects in Vocabulary Learning ……… 29

b. Intentional vs. Incidental Vocabulary Learning ………... 31

3. Learning Strategy ………. 35

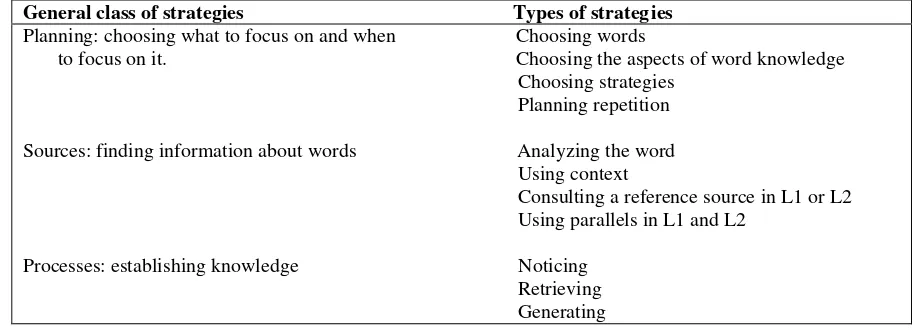

4. Strategies in Vocabulary Learning………. 39

a. Definitions ………..……….. 39

b. Types of Vocabulary Learning Strategy……… 41

1) Memorizing Strategies ………. 44

2) Cognitive Strategies ………... 46

3) Metacognitive Strategies ……….……….. 47

4) Social Strategies ……… 48

CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY

A. Research Design ……… ... 56

B. Nature of Data ……… .. 58

C. Data Setting and Participants ……… .... 58

1. Setting ……… . 58

2. Participants ……… .. 59

D. Data Gathering Instruments ………. 59

E. Data Collection Procedure ……… .. 60

F. Data Processing ……… ... 62

G. Data Analysis Procedure……… .. 63

H. Validating the Research Findings ……… 63

CHAPTER IV RESULTS AND DISCUSSION A. Student‘s Background Experience in Learning Vocabulary ……… 64

B. Student‘s Action in Learning Vocabulary……… 70

1. The Actions to Find the Meaning of Unknown Words ……… 70

2. The Actions to Retain the Words in Long-Term Memory ……..……… ... 79

3. The Actions to Recall the Words at will ……….………… ... 86

4. The Actions to learn Using the Words in Spoken and Written Mode……… ... 89

a. The Actions to learn Using the Words in Spoken Mode……… ... 89

b. The Actions to learn Using the Words in Written Mode……… ... 95

C. Student‘s Intention in Learning Vocabulary ……….. 97

CHAPTER V CONCLUSION A. Conclusion ………... 101

B. Suggestion ……….. . 104

REFERENCES ………. 106

LIST OF TABLES

1. Table 2.1 Knowing a word ……….. 20

2. Table 2.2 Kinds of vocabulary knowledge and the most effective kinds of learning …. 34 3. Table 2.3 Definitions of learning strategies ……… 34

4. Table 2.4 Features of language learning strategies ………. 35

5. Table 2.5 Classification of learning strategies ……… 38

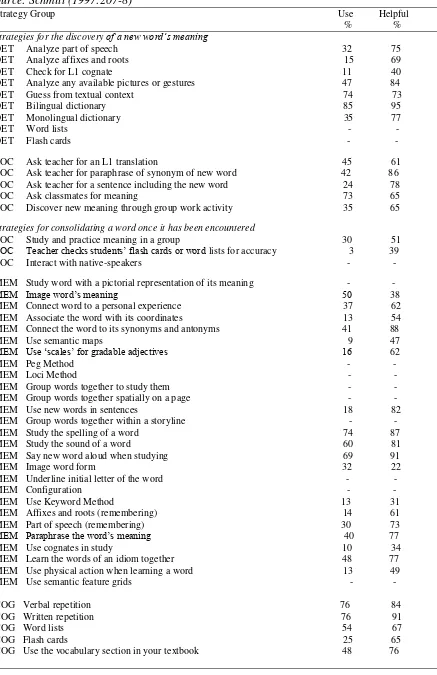

6. Table 2.6 A taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies ……… 41

7. Table 2.7 A taxonomy of kinds of vocabulary learning strategies ………. 43

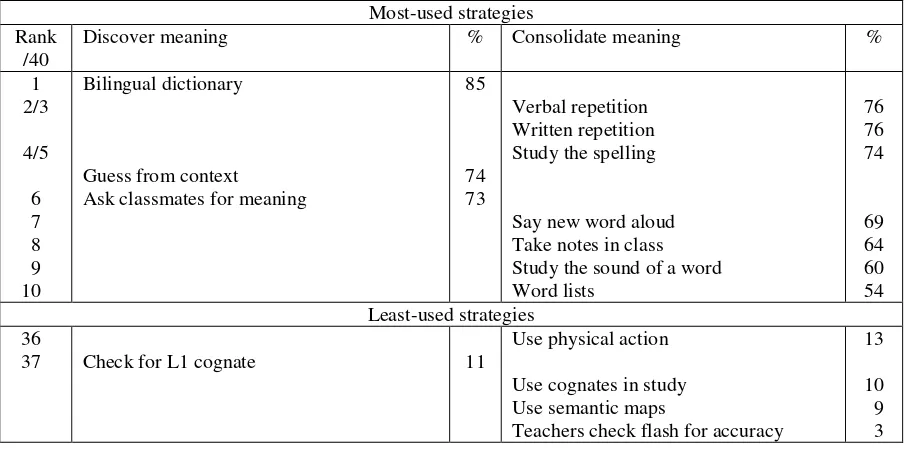

8. Table 2.8 Most- and least-used strategies ……… 49

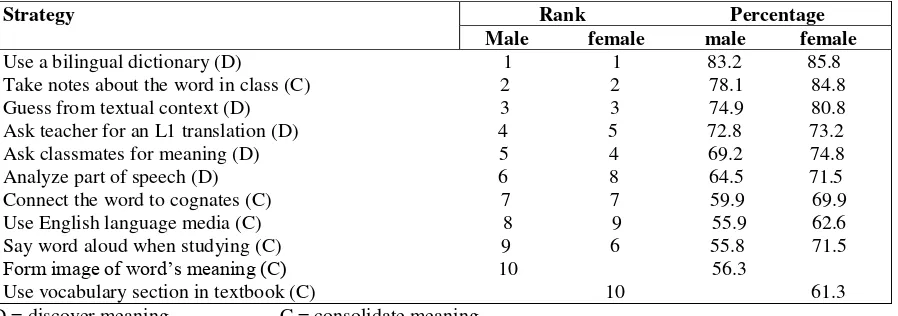

9. Table 2.9 The ten most frequently used vocabulary strategies……… 50

10. Table 2.10 The ten least frequently used vocabulary strategies ……….. 51

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF APPENDICES

1. The result of interview (in Indonesian) 2. The result of interviews (in translation) 3. Vocabulary test

4. The result of vocabulary test

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

This introductory chapter contains six major sections, namely; the background of the study, problem identification, problem limitation, research questions, research goal and objectives, and research benefits.

A. Background of the Study

This section presents three sub-sections forming the background of the current study. They are the role of learning strategy to the success of L2 learning, the role of vocabulary in the context of L2 learning and relevant research on vocabulary learning.

1. The Role of Learning Strategy to the Success of L2 Learning

It is very likely that the success of language learning process cannot be separated from the learning strategies used by the learners. Every time the students learn the language skills and elements, they most possibly apply some language learning strategies. The strategies are applied during the learning process so that they determine its result. The underlying problem apparently lies upon the condition whether the students realize their learning strategies or not, and whether they apply the strategies appropriately or not. If the learners use the learning strategies properly, the learning process will essentially give better result or vice versa. This indicates that language learning strategies constitute an important aspect that must be considered to get the success of language learning process. Learning strategies are viewed as the special thoughts or behaviors that individuals use to help them comprehend, learn, or retain new information (O‘Malley & Chamot, 1990:1). In other words, learning strategies are

It is quite understandable that language learning strategies enable the learners to manage their own learning. The language learning strategies will lead the learners to learn in a more intensive and more directive way. This is an important contribution of learning strategies to the success of language learning process. Oxford (1990) has given her prominent views on learning strategy. She insists that learning strategies are very important particularly

for language learning, in that they are tools for the learners‘ active and self-directed

movement, which is essential to develop communicative competence (p.1). Because they are tools, students must be able to make use of them to make their learning much easier, more directive, and more effective. She also argues that self-directed students gradually gain greater confidence, involvement, and proficiency (p.10). Using language learning strategies as tools for language learning, the students will not only be passive learners, but they will be active and self-directed in their learning. In a more detail definition, she describes learning strategies as specific actions taken by the learner to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations (p.8). This shows that the main purpose of using learning strategies is basically to make learning easier and more efficient. Moreover, it must also be applicable to different conditions so that it can increase students‘ control of their own learning.

learning is to be able to communicate in English, language learning strategies must be applied appropriately in the learning process. If not, it will be more difficult to reach the goal.

Looking into most English classes in Indonesia, however, it seems that reaching the goal of English learning is still far beyond the reality. Most of the students have little knowledge of how to learn English in an appropriate way. They also still do not understand what language learning strategies are. They do not know what learning strategies that must be used in learning certain language skills and language features, how to apply the strategies in the learning process, and why they should apply certain learning strategies to learn certain

language skills and elements. The conditions hinder students‘ success in learning English as a

foreign language. This means that students‘ knowledge and awareness of learning strategies

cannot be ignored in the learning process. Therefore, the important thing here is how to make the students realize their learning strategies and how to apply them in the learning process.

2. The Role of Vocabulary in the Context of L2 Learning

This research focuses on the strategy for learning vocabulary because vocabulary is one of the important elements in language learning. The main goal of studies on vocabulary learning strategy is to discover how words are learned and what part is played by different processes such as; lexical inferencing, guessing the meaning of words from context, memory processes, lexical simplification, and finally lexical transfer from L1 to L2 (Catalan, 2003:57). This indicates that vocabulary learning is not a simple matter. It needs serious attention from both learners and teachers. Furthermore, some other experts insist the importance of vocabulary in L2 learning. Gass (1999:325), for instance, states that learning a second language means learning its vocabulary, and knowing the meaning is the main point of knowing the lexical items. This indicates how important vocabulary learning in the context of L2 learning is. Moreover, vocabulary or lexicon may be the most important language component for learners (Gass & Selinker, 2001:372). It is not to say that vocabulary knowledge means everything in L2 learning. Nevertheless, it seems very influential among the various aspects which must be dealt with in L2 learning. It underlies all skills in language performance. This is in line with the opinion that words are an important part of linguistic knowledge because without words we would be unable to convey our thoughts through language (Fromkin, David Blair & Peter Collins, 2000:60). For that reason, knowing the how to get sufficient vocabulary knowledge must receive adequate attention in language learning.

In L2 learning, the learners do not only learn to understand the language but also to produce or to use it. In this case, vocabulary is always needed whenever the language learners

learn to improve their L2 performance and competence. Learners‘ language performance—

in using the language both receptively and productively if they do not have adequate vocabulary knowledge.

L2 learners may encounter difficulties in using the language receptively and productively. Many of the difficulties in both receptive and productive use of language are perceived by the learners as a result of their inadequate vocabulary (Nation, 1990: 2). This is in line with what I experience in my English class. When the students are asked to communicate in English, they cannot do it. They state that they get difficulties in using English because they do not know the words they want to use. They do reading but they do not know the meaning of the sentences and even the words they read. They want to speak English but they do not know the words to speak. They listen to spoken English but they cannot understand it. And they want to write but they do not have enough words to express their ideas. Feeling that they still lack of vocabulary, the students become reluctant to use the language.

At some point, L2 students are aware of their insufficient vocabulary. Their awareness is about the degree to which their limited vocabulary knowledge hinders their ability to communicate effectively in the target language (Read, 2004: 146). This indicates that

adequate vocabulary underlies students‘ ability to communicate in L2. The condition arises

from the fact that lexical items carry the basic information load of the meanings they expect to

comprehend and express (Read, 2004: 146). This means that students‘ insufficient vocabulary

becomes an obstacle for the development of their communicative competence. This condition

in turn hampers students‘ success in English learning.

point, the vocabulary learning strategy plays an important role to empower the students in learning vocabulary. That is why a research on this issue is quite relevant to do.

3. Relevant Research on L2 Vocabulary Learning and Acquisition

Studies on second language vocabulary reached a peak in the 1990s and early 2000s (Read, 2004: 146). Different issues on vocabulary learning have been the focus of the studies. Nevertheless, the new views in a series of diverse research fields have contributed to the understanding of vocabulary development and research on vocabulary acquisition has constructed itself as the main attention of language acquisition researchers (Henriksen, 1999:303). This shows that research on vocabulary learning is getting more meaningful and interesting.

Among the varieties of issues in vocabulary acquisition studies, the notion of incidental and intentional vocabulary learning is the one which may explain how the learners learn new words. In incidental vocabulary learning the students acquire word knowledge incidentally as the result of their major learning activity inside or outside the classroom, whereas in intentional vocabulary learning the students acquire word knowledge through the activity that is mainly aimed to improve their vocabulary knowledge (Read, 2004:147). In this case, we can see more clearly the difference between the two models of vocabulary learning. Since in incidental vocabulary learning the students learn the new words unintentionally, they

possibly do not apply any learning strategy in it. In this model of learning, the student‘s

attention in learning is not on the words but on something else—most likely the content of a text. Vocabulary learning in which the learners try to comprehend unknown words that they

hear or read in context is called ―incidental‖ because it occurs when learners are focused on

strategy because they already know the direction and the purpose of their learning, namely to improve their word knowledge. Therefore, they do it in a fully conscious and self-directed way.

A set of research reports was given by different researchers. An overview of the research findings and issues covering a set of research reports on incidental learning of L2 words both from spoken and written input was given by Wesche and Paribakht (Read, 2004:147). They conducted an introspective study on how the learners treat the unknown words in order to comprehend the written text they read. In the study they identified learners‘ lexical processing strategies and developed a taxonomy of learner knowledge sources and cues used in determining words meaning (Weshe and Paribakht, 1999:178). Meanwhile

Swanborn and de Glopper (2002) focused on the influence of readers‘ purpose and level of

reading ability in incidental learning of words (Read, 2004:147). Concerning the spoken input, a research by Vidal (2003) proved that the knowledge of small but significant number of words was keep in mind by the students by means of naming, definition, or description (Read, 2004:147). Differently, Wode conducted a research on the nature of the lexical knowledge acquired by learners in secondary school foreign language immersion (IM) program versus outcomes from alternative instructional settings (Wesche and Paribakht,

1999:178). He found that learners‘ L1 functions as the basis for their approach to the word

class system of the target language and IM provides a lot of chance for incidental learning (Wode, 1999:254). Another researcher, Hulstjin (2001) discussed incidental and intentional vocabulary learning from psycholinguistic point of view. He argued that in research studies the difference between the two models of vocabulary learning can be preserved by directing

learner‘s attention toward or away from the words although its significance in influencing

learners‘ long term memory of the words is theoretically slight (Read, 2004:147). This may

Furthermore, he stated that in the classroom context both incidental and intentional learning of vocabulary should be regarded as complementary activities (Read, 2004: 147-48). This means that the two learning models can be applied simultaneously to give better result of the learning process.

Citing Lewis (1993), Sokmen (1997) stated that at the entrance of 21st century vocabulary acquisition has held a more important role, that is, the central role in second language learning (in Schimtt & McCarthy, 1997:237). This is viewed as a change of concern, in that the teacher is encountered with the challenge of how best to assist students memorize and get back L2 words. Related to the effort for helping the students memorize and recall L2 words, the use of learning strategy may have meaningful contribution to students‘ learning.

Particularly in Indonesian context, research on vocabulary size shows that the vocabulary mastery of Indonesian students is still very limited. This can be seen in the study conducted by Quinn (1968) which revealed that on average the students had only mastered less than 1000 of the most frequent words after six years study in high school (Nurweni &

Read, 1998:162). Even eight years later, a study by Nation (1974) found that the students‘

recognition vocabulary was still around 600 words (Nurweni & Read, 1998:162). Although a more recent study by Nurweni (1990) showed that the students had known a larger number of

words than those in Quinn‘s research, their vocabulary size was still below 4000 words which

is the vocabulary size that they have to master in high school (Nurweni & Read, 1998:162). These indicate that Indonesian students still lack of English vocabulary and need to improve it in their further learning.

In their latest study, Nurweni & Read (1998) measured the vocabulary size of

first-year students of a university in Sumatra. They estimated students‘ vocabulary based on the

result proved that the students mastered an average of 1226 (44%) of the 2800 words. This also proved that their vocabulary size was far below the target of 4000 words recommended in the national curriculum for senior high schools in Indonesia.

Studies conducted by Quinn (1968), Nurweni (1990), and Nurweni and Read (1998) proved that vocabulary size of Indonesian students still did not meet the requirements stated in the national curriculum. This fact indicates that the students still have inadequate vocabulary mastery particularly to communicate in English. Hence, further research on the

aspects influencing students‘ vocabulary mastery is needed. One of the important aspects is

the strategy used in learning vocabulary. It seems to be the most important aspect to the success of vocabulary learning. Research on it may reveal what the student actually does to learn L2 vocabulary, how far she/he understands strategies for L2 vocabulary learning, how the strategies are employed, and how the strategies improve student‘s autonomy or independence learning L2 vocabulary. Theoretically if the student applies an appropriate strategy which is also suitable for her/him, the learning process will give better result. For that reason, the current research will focus on investigating student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary.

B. Problem Identification

more encouraged in using English both receptively and productively. This also means that the success in learning English becomes much closer and easier.

Dealing with vocabulary learning, the interesting questions to pose in this field are: How can vocabulary be learned effectively? What strategy should the student use in learning vocabulary? How should the student apply the strategies to learn vocabulary? What factors

influence student‘s vocabulary learning? What learning environment supports vocabulary

learning? What kind of curriculum must be developed and implemented in vocabulary learning-teaching process? What must the teachers do in managing their vocabulary instruction? And what are the roles of vocabulary learning in second language learning?

C. Limitation of the Study

Among the various interesting problems recognized in the problem identification, the important thing to be taken into account in the current study is what strategy the student may use in learning L2 vocabulary. It is impossible to investigate the problems altogether in the current study because of my limited time and capability. Besides, this study relies on the students who have the highest vocabulary size or who are considered as successful learners. Thus, it describes only the vocabulary learning strategy used by the successful students. It does not include the students having lower vocabulary mastery in the data gathering process. It is possible, therefore, that this study does not describe vocabulary learning strategy from the point of view of less successful students. In other words, the description of vocabulary learning strategy in this study is limited to the strategy applied by the successful students.

comprehensively. The experiences of using a vocabulary learning strategy in the previous learning can be used as a guide to determine the action which must be taken later and as a reflection for improving further vocabulary learning. Meanwhile, student‘s intention in vocabulary learning may affect student‘s seriousness in learning vocabulary and possibly in selecting the appropriate strategy.

The student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary becomes the focus of the study because it constitutes a factor by which the student can develop her / his ability in managing, controlling, and directing the learning, and finally she / he can be less dependent to the teachers. This means that the learning strategy helps the student become more autonomous, empowered, self-directing, and self-fulfilling in the learning process. This will finally lead the student to the success of vocabulary learning. For that reason, the study attempts to describe and identify student‘s experience, action, and intention in learning English vocabulary.

D. Research Question

Based on the problem identification and limitation, the study aims to address the research question below:

What is student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary?

E. Research Goal and Objectives

The study focuses on investigating how the student learns vocabulary. More

specifically, it investigates student‘s background experience, action, and intention in learning

vocabulary. Therefore, it attempts to reach the following goal and objectives. The goal of the research is to describe and identify student‘s strategy in learning vocabulary. More specifically, the research also aims at reaching the subsequent objectives: (1) to describe

(a) finding out the meaning of unknown words, (b) memorizing the words and their meaning, (c) recalling the meaning of words when they are met, and (d) learning how to use the words in written and spoken form; and (3) to identify student‘s present and future intention in learning vocabulary.

F. Research Benefits

The interpretation of the narrative will contribute to the language learning theories. Theoretically, the result of the study may explain how learning strategy becomes an important and decisive factor in L2 learning, particularly in learning vocabulary seen from student‘s

point of view. In this case, the description of student‘s background experience, action and

intention in learning vocabulary may bring one step further toward a more comprehensive and realistic theory of how vocabulary learning strategy works, seen from the student‘s perspective.

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter consists of two major sections, namely theoretical review, and theoretical framework. The first section, theoretical review, presents the review of related theories which elaborates the nature of vocabulary knowledge, language learning strategy, and vocabulary learning strategy. And the second section describes the theoretical framework of the current study.

A. Theoretical Review

1. The Nature of Vocabulary Knowledge

The discussion of vocabulary knowledge in this section begins with the existing definitions of a word, continues with the aspects of knowing a word, breadth vs. depth of vocabulary knowledge, and receptive vs. productive vocabulary knowledge.

a. Definition of a Word

words and the concept of meaning. The problem with this definition is on particular meanings which are carried by more than one word. It is not easy to determine whether they should be regarded as one word or more than one word. Another definition of a word is related to its pronunciation, that is, it will not have more than one stressed syllable (Carter, 1998:6). The problem with this definition lies upon the words, e.g. prepositions and conjunctions, which are not usually stressed.

b. Knowing a Word

In order to get clearer insight of a word, it is necessary to know the aspects of word knowledge. Generally, the discussions of what is meant by knowing a word emphasize the knowledge of word forms, their meanings, and their linguistic features, and the ability to use words in different modalities and varied linguistic settings (de Bot, T.S. Paribakht & M.B. Wesche, 1997:310). Besides, word knowledge has also been described as consisting of some components. Richards (1976:83) suggests some features or assumptions of word knowledge. He states that knowing a word entails: (1) knowing the degree of probability of encountering that word in speech or print and the sort of words most likely to be found associated with the word. This assumption suggest that word knowledge covers the knowledge of the frequency of the word and its collocation, (2) knowing the limitations imposed on the use of the word according to variations of function and situation, (3) Knowing a word means knowing the syntactic behavior associated with the word. This shows that knowledge of word comprises the understanding of relationships between specific grammatical features and the word, (4) Knowing a word entails knowledge of the underlying form of a word and the derivations that can be made from it. This feature implies that knowledge of words involves the knowledge of word inflections and the use of affixes, (5) Knowing a word entails knowledge of the network of associations between that word and other words in the language. This indicates that lexical knowledge includes the understanding of the association between the word and other words, (6) Knowing a word means knowing the semantic value of a word, and (7) Knowing a word means knowing many of the different meanings associated with a word. This covers the understanding of various meanings based on the context in which the word is used. The seven aspects provide clear points that must be considered in learning vocabulary.

improvement (Jordan, 1997:149). The learners tend to view vocabulary mastery as meaningful development in their learning. This indicates that vocabulary knowledge is very important for them to evaluate their progress in learning L2. Therefore, it is necessary for them to know what skills involved in knowing a word. Wallace (1982) as cited by Jordan (1997:150) describes word knowledge as the ability to: (a) recognize it in its spoken or written form, (b) recall it at will, (c) relate it to an appropriate object or concept, (d) use it in the appropriate grammatical form, (e) pronounce it in a recognizable way, (f) spell it correctly, (g) use it with the words it correctly goes with (collocation), (h) use it at the appropriate level of formality and (i) be aware of its connotations and associations. The description also covers the knowledge of form, meaning and use of words.

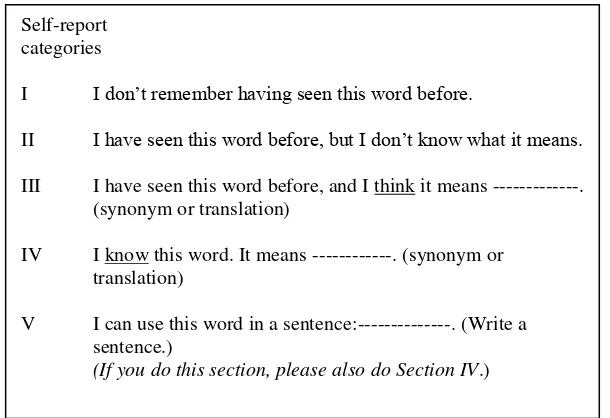

of vocabulary. At this stage the learners are able to use the word in a sentence. The five stages or categories are shown in Figure 2.1 below:

Figure 2.1 VKS elicitation scale—self report categories Source: Paribakht & Wesche ( 1997:180)

c. Categories of Word Knowledge

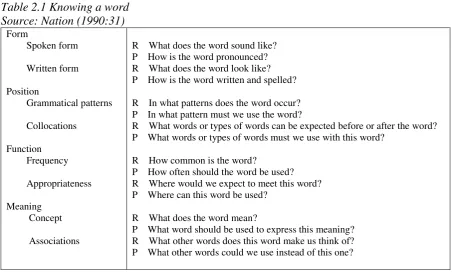

Different categories of word knowledge are pointed out by Nation (1990). He identifies four categories of word knowledge as shown in Table 2.1. According to Nation, knowing a word means; (1) knowing its form, (2) knowing its position, (3) knowing its function, and (4) knowing its meaning. Firstly, knowledge of word includes the knowledge of word form. This category covers both the spoken and written form of the word. It comprises three aspects, namely, knowledge of the spoken form, knowledge of the written form and knowledge of word parts. Knowing the spoken form of the word includes being able to recognize the word when it is heard and being able to produce the spoken form in order to express a meaning (Nation, 2001:40). When the learners know the spoken form of a word, it means that they are able not only to catch the spoken word but also to pronounce the word, including the particularly-stressed syllables in the word. While, knowing the written form of

Self-report categories

I I don‘t remember having seen this word before.

II I have seen this word before, but I don‘t know what it means.

III I have seen this word before, and I think it means ---. (synonym or translation)

IV I know this word. It means ---. (synonym or translation)

V I can use this word in a sentence:---. (Write a sentence.)

the word, is mainly related to the spelling of the word. One aspect of gaining familiarity with the written form of words is spelling (Nation 2001:44). It means that knowledge of word spelling is the centre of knowing the written form of the word. Furthermore, Nation argues that the ability to spell is most strongly influenced by the way learners represent the phonological structure of the language. This implies that the knowledge of sound system of the language underlies learners‘ capability to represent the spoken form of words into the written form. He also insists that the spoken form of words can be represented in learners‘ memory in different ways: as whole words, as onsets (the initial letter or letters) and rimes (the final part of a syllable), as letter names, and as phonemes. And, the last aspect of knowing word form is the knowledge of word parts. It is closely related with morphology--the internal structure of words and the rules by which words a re formed. Knowledge of a language implies knowledge of its morphology (Fromkin, David Blair & Peter Collins, 2000:66). It involves the understanding of affixes and stems in making up the words. This may help the learners learn both the meaning and the form of the words because of the fact that; the affixes often have their own meaning. For example, the prefixes il-, im-, ir-, dis- and un- carry negative meaning of the word. The specific meaning they carry may facilitate language learners to store the meaning in mind. And, some other affixes change the parts of speech. The prefixes em- / en-, for instance, and the suffixes; -en, -ize, -ate, and –ify change an adjective into a verb. In addition, there are also some suffixes forming noun, such as; –ion, -ment, -ness, -dom, -ity, -er / -or, -ant, -ance and –ence, some others forming adjectives and also adverbs. This process is covered in morphology or the study of word formation (Gass & Selinker, 2001:9). In brief, identifying various affixes forming different parts of speech may help learners remember the words.

a word is related to the use of the word in a sentence. Hence, it has close relationship with grammatical behavior of the word. For instance, in what sentence patterns the word may occur and can be used whether as subject, verb, object, adverb, complement, or other functions the word may have. Thus, the knowledge of parts of speech of a word and its grammatical patterns is needed. Grammatical learning burden of a word depends on the parallel in grammatical behavior between words of related meaning (Nation, 2001:56). This implies that the grammatical similarity of the words having related meanings will reduce the learning burden of the words. Therefore, knowing a word involves knowing its grammatical behavior. Furthermore, knowing a word also implies knowing the words it commonly collocates with. Knowing its collocations means knowing what words it typically occurs with (p.56). This feature includes the knowledge of the words or types of words most likely appear before or after the word, and that of the words or types of words that must be used with the word. Besides, the knowledge of collocation is important in vocabulary knowledge because it covers the stored sequences of words which serve as the bases of learning, knowledge and use (p.321). This indicates the apparent position of collocation in vocabulary knowledge.

distinctive frequency of a word. Moreover, it is said to be different across cultures. It is understandable, therefore, that it is most likely influenced by the context in which the word is used. Undoubtedly, different countries may provide different contexts of using the word because of their different cultural settings. It can be said that certain words or terms commonly used in a country, especially the terms referring to certain cultures, may not be frequently used in different countries. The term ‗bull-fighting‘, for example, will be familiar and frequently used in Spain but it will not in other countries which do not have the similar

culture. This happens because ‗bull-fighting‘ is one of the cultural backgrounds in Spain. The

use of the term is limited to particular cultural settings. In brief, knowledge of word use entails the understanding of usage limitations of the word.

Table 2.1 Knowing a word

R What words or types of words can be expected before or after the word? P What words or types of words must we use with this word?

knowing the form and meaning—because it establishes the learners‘ readiness in retrieving the meaning when seeing or hearing the word form or getting back the word form when wishing to express the meaning (p.48). It seems that knowing the meaning of the word cannot be separated from the knowledge of its form. Therefore, the relationship between meaning and form constitutes a significant concept of knowing a word. Knowing a language means knowing how to relate sounds and meaning (Fromkin, David Blair & Peter Collins, 2000:4). It can be concluded, then, that form-meaning connection finally may lead the learners to be able to understand and produce the word.

stored in human memory. In this case, language users have a fundamental concept of a word which is suitable with a set of meanings of the word in use, and language learners have to determine what real items the word refers to (Nation, 2001:50). It is in line with what Carter (1998:15) says that lexical words have a referent and it is almost impossible to communicate in a language without reference. Seeing the importance of reference in communication, it is necessary to identify what is meant by referent. A referent is the object, entity, state of affairs, etc. in the external world to which a lexical item refers (Carter, 1998:15). For this reason, it is acceptable that knowing the meaning of a word also entails the knowledge of concept—what the word means, and referents—what the word refers to.

Dealing with vocabulary learning, Bogaards (2000) argues that L2 learners may be assumed to learn not only word but lexical units. In this case, he identifies six aspects of lexical knowledge, namely; form, meaning, morphology, syntax, collocation, and discourse. The first five elements are the similar aspects mentioned by other experts. The sixth aspect— discourse, however, is a deeper knowledge of vocabulary. It deals with knowledge of styles, register, and appropriateness of particular senses of a same word which is not easy for L2 learners to acquire (Bogaards, 2000:493). In other words, the last aspect—discourse—is strongly related with the context of language use. It means that there is certain role played by vocabulary in a discourse. In this case, Nation (2001:205) identifies two aspects related to vocabulary use in a text, namely; vocabulary use signals and contributes to the uniqueness of the text—what makes the text different from other texts, and vocabulary use carries general discourse messages shared with other similar texts. This shows the importance of vocabulary use in carrying the communicative purposes of a text.

Knowledge of vocabulary can be viewed from different perspectives. Among the

various views, the notion of ‗breadth and depth of knowledge‘ and ‗receptive and productive

description of vocabulary knowledge, the following sub-sections present the discussion of various ideas given by different experts.

d. Breadth vs. Depth of Knowledge of Vocabulary

The term ‗breadth of vocabulary knowledge‘ usually refers to vocabulary size of the

learners. Vocabulary size refers to the number of words that a person knows (Read, 2000:31). Learners‘ vocabulary size is most likely related to their ability in understanding both written and spoken texts. This implies that the greater vocabulary size the learners have, the more easily they understand the texts they read or listen. This also means that vocabulary knowledge mainly deals with the range of different words and proper understanding of the words. Nonetheless, it should not be supposed that if a learner has adequate vocabulary then all aspects in language learning become easy and it should not also be thought that significant vocabulary knowledge is always a prerequisite to language skill performance (Nation & Waring, 1997 in Schmitt & McCarthy, 1997:6). To this extent, knowledge of words is operationalized as the ability to translate L2 vocabulary into L1, to define the word correctly, or to say the word differently and therefore, vocabulary knowledge is defined as precise comprehension (Henriksen, 1999:305). This stage of vocabulary knowledge falls into the

‗partial-precise knowledge‘ of vocabulary.

Various studies on vocabulary size, lexical growth, and the number of words gained overtime have been conducted by different researchers. The focus of such studies is mainly on measuring the number of vocabulary, such as; counting the number of words recognized by

native speakers (D‘Anna, Zechmeister, & Hall, 1991; Goulden, Nation, & Read, 1990), the

applying different exercises, techniques and strategies (Avila & Sadoski, 1996; Cohen & Aphek, 1980). Such research, however, does not lead to sufficient understanding of vocabulary acquisition and does not explain how individual words are acquired (Schmitt, 1998:282). This condition underlies the emergence depth of knowledge perspective which likely clarifies the issue.

The proponents of depth of vocabulary knowledge (Paribakht & Wesche, 1993, 1997; Read, 1993; Schmitt, 1996; Viberg, 1993; Wesche & Paribakht, 1996) state that most of the existing vocabulary tests or the traditional vocabulary tests only measure partial knowledge, particularly recognition. Therefore, they develop tests to measure wider and deeper aspects of lexical knowledge. Using such tests, they assess the aspects such as; basic understanding, full understanding, correct use, sensitivity to collocation and word association. Nevertheless, different test models should be accommodated in order to cover various features of knowledge being tested. Henriksen (1999) argues that researchers must use a combination of tests formats tapping distinct aspects of knowledge to describe a learner‘s lexical competence related to the aspects of quality or depth of vocabulary knowledge (p.306). In their research, Laufer & Paribakht (1998) classify word knowledge into three types, namely, passive, controlled active and free active knowledge. Passive vocabulary knowledge is defined as understanding its most frequent meaning. Controlled active knowledge is described as a cued recall of the word. And free active knowledge is referred to spontaneous use of a word in context. The three aspects show that what they investigate is fairly deeper than merely word recognition which is the concern of breadth of vocabulary knowledge.

Furthermore, he argues that the ability to measure the degree of depth of knowledge for each word is needed in investigating the incremental acquisition of individual words. Involving the four aspects in the study will likely lead to a better explanation of how the words are acquired.

e. Receptive vs. Productive Knowledge of Vocabulary

Knowledge of a language makes it possible to understand and produce new sentences (Fromkin, David Blair & Peter Collins, 2000:7). This implies the notion of receptive and productive use of language. Hence, the knowledge of vocabulary is essentially needed to support the language use. This signifies the emergence of the term ‗receptive‘ and

‗productive‘ knowledge of vocabulary. This term is widely used although in terms of lexicon

1997:88). This shows that there is still not any clear definition of what is meant by reception and production. Nevertheless, vocabulary knowledge can be best represented as a continuum with the initial stage being recognition and the final being production (Gass & Selinker, 2001:375). It means that reception or recognition cannot be separated from production but it must be viewed as an interrelated process.

The dichotomy between reception and production looks convenient for vocabulary teaching especially for some practical and pedagogical purposes but the two notions should be avoided and even abandoned because of their fuzziness (Melka, 1997:99). This is overtly contradictory to the fact that empirically the term is commonly used to refer to the ‗passive‘

and ‗active‘ use of language. As a matter of fact, vocabulary, as the centre of the language,

always plays its role in both passive and active use of language. Besides, most models of lexical knowledge distinguish between passive/receptive and active/productive vocabulary (Laufer & Paribakht, 1998:368). The passive use of language is mostly related to two language skills, namely, listening and reading. This can be seen in that the aim of listening activity is to understand the spoken language and that of reading is to comprehend the written text. The process of understanding occurs in mind. The language users most likely use their knowledge of vocabulary to comprehend the meaning of the spoken / written texts. Researchers agree that word comprehension does not automatically determine the accuracy of word use and that passive/receptive knowledge generally precedes active/productive knowledge (Laufer & Paribakht, 1998:369). At passive/receptive level, therefore, the language users mostly do not produce any spoken / written language. That is why it is called the passive use of language.

communicating the writer‘s ideas to the reader. Therefore, written language is produced as a means of conveying the ideas. It seems clearer now that in listening / reading the listener / reader uses the language passively, whereas in speaking and writing the language is used actively.

The receptive and productive knowledge of vocabulary is discussed comprehensively by Nation (1990:31-33). He argues that the receptive dimension of vocabulary knowledge entails; (1) being able to recognize it when it is heard or when it is seen, (2) having an expectation of what grammatical pattern the word will occur in, (3) having some expectation of the words which will collocate with it, (4) knowing its frequency and appropriateness, (5) being able to recall its meaning, and (7) being able to make different associations with other related words. Similarly, productive knowledge also covers some aspects of vocabulary knowledge which expand the receptive knowledge. Productive knowledge of vocabulary involves; (a) knowing how to pronounce the word, (b) how to write and spell it, (c) how to use it in correct grammatical patterns along with the words usually collocate with, (d) how to avoid using low frequency word too often and use it in suitable situations, (e) how to use the word to stand for the meaning it represents, and (f) how to be able to think of suitable replacement of the word (if there are any). Those aspects including the scope of receptive and productive knowledge are classified into four categories of knowing a word; knowing its form, knowing its position, knowing its function, and knowing its meaning. (see Table 2.1).

2. Vocabulary Learning

a. Some Aspects in Vocabulary Learning

observe how well it has been learned and used (Nation, 2001:395). This indicates the complexity of the aspects of vocabulary learning goals. It means that reaching the goals of vocabulary learning is not as simple as it is suppose to be. Therefore, believing that a learner hears or memorizes a word with the consequence being full knowledge of the word is unrealistic (Gass & Selinker, 2001:381). It is enough, possibly, to consider what learners do when they face with unknown words. In the context of foreign vocabulary learning, the learners do not only learn words but lexical units (Bogaards, 2000:492). What must be made clear, in this case, is what is meant by ‗lexical units‘. Following Cruse (1986), Bogaards (2001) describes ‗lexical units‘ as the smallest parts that must have at least one semantic constituent and must consist of at least one word (p.325). The definition shows that in terms of lexical unit a meaning can be represented by one word or more. In this sense, affixes are not lexical units because they are not words. Although they have their own meaning, the meaning will come true only when they are bound with suitable words. According to Bogaards, foreign vocabulary learning entails one or more of the following features; (1) learning unknown form and a new meaning, (2) learning a new meaning for an already known form, (3) learning a new meaning for a combination of already known forms, (4) learning semantic relations between lexical units, (5) learning morphological relations between lexical units, (6) learning correct grammatical uses of lexical units, (7) learning common collocations, and (8) learning the proper use at pragmatics and discourse level. In general, the aspects fall into three kinds of vocabulary knowledge introduced by Nation (1990) -- knowledge of form, meaning, and use.

consisting of the basic free morpheme, word derivations and inflections, (c) syntactic pattern of the word, (d) meaning including referential (range of meanings and metaphorical meanings), affective (connotations) and pragmatic (suitability of word in context), (e) lexical relations with other words (synonymy, antonymy and hyponymy) and (f) collocations. Preferably, language learners must be familiar with all of the aspects. But, it seems unlikely to do because the aspects are very complex and too complicated for L2 learners to master. In the context of L2 learning, therefore, partial knowledge of the aspects is reasonable and acceptable. The learners may be have mastered some properties of words but not the others (Laufer, 1997:142). This implies that incomplete mastery of word knowledge is normal in language learning, particularly L2 learning.

Taking into account what learners do or try to do with words, Gass & Selinker (2001:382-93) describe four lexical skills involved in vocabulary learning, namely; (1) production in which the learners attempt to use the words they learn to create sentences, (2) perception which deals with learners‘ effort to perceive the words in the ongoing speech or conversation, (3) word formation in which the learners learn to combine derivational elements forming new words, and (4) word combination, collocations, and phraseology which concern

with learners‘ attempt to recognize idioms and multiword structures that signify a particular

meaning. Thus, the aspects of word knowledge may serve as the base for vocabulary learning process.

b. Intentional vs. Incidental Vocabulary Learning

Dealing with vocabulary learning, it is commonly associated with the term ‗intentional

vs. incidental‘ vocabulary learning. This term is identical with the notion of ‗explicit vs.

1999:182). The distinction between the two models of learning lies upon learners‘ goals in learning. It is called incidental, implicit, or unconscious vocabulary learning when it aims at comprehending the meaning, whereas intentional or explicit or conscious vocabulary learning occurs when its goal is explicitly to learn new words.

Wode‘s definition is possibly the most specific in this sense, that is, language learning is a by-product of language use by the teacher or by anyone else in the classroom, without the linguistic structure itself being the focus of attention or the target of teaching maneuvers (Wode, 1999:245). In the same way, most papers in this issue define incidental as something that is learned without the object of that learning being the specific focus of attention in a classroom context, that is, incidental learning is a by-product of the classroom focus (Gass, 1999:320). This means that in incidental vocabulary learning the focus of learning activity is on something else rather than on learning words. Further, Gass (1999:322) suggests three requirements for learning words incidentally; (1) there are known cognates between L1 and L2, (2) there is large L2 exposure, and (3) the L2 related words are recognized. In addition, he views the notion of intentional vs. incidental learning as a continuum shown in the following figure.

Intentional Incidental

no cognate cognate

first exposure more exposure lots of exposure

no known L2-related words known L2-related words

Figure 2.2 Intentional versus incidental learning Source: (Gass, 1999:322)

learning can be identified at experimental level, particularly in investigating the learning. Experimentally, the learners in incidental vocabulary learning are asked to do a task processing of some information without being told that they will be tested afterwards. On the other hand, in explicit learning they are told that their recall of information will be tested in advance (Laufer & Hulstijn, 2001:10). The information about what will be given after the learning process, particularly a test, increases learners‘ consciousness in the learning process. For that reason they perform explicit learning.

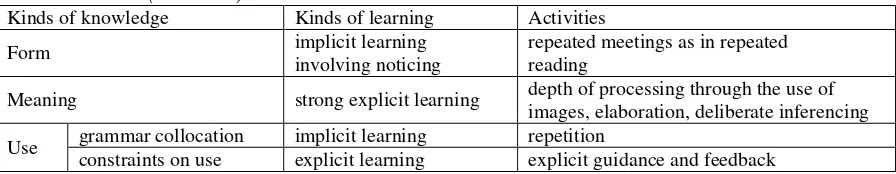

Different aspects of word knowledge lead to the discussion of implicit and explicit learning. N. Ellis (1994) as cited in Nation (2001:33) states that knowing a word involves two aspects, that is, the form aspects (Input/Output aspects) and the meaning aspects of vocabulary learning. The base of this differentiation is on the kind of learning which is matched with the two distinct aspects. In this case, two kinds of learning are identified, that is, explicit and implicit learning. The distinction between explicit and implicit learning is that the formal recognition and production rely on implicit learning, while the meaning and linking aspects rely on explicit, conscious process (N. Ellis, 1994. cited in Nation, 2001:33). This implies that both receptive and productive knowledge can be acquired through implicit or unconscious learning. According to Ellis, implicit learning focuses on the stimulus and is strongly influenced by repetition. On the other hand, learning the meaning and the related aspects is done consciously. The quality of mental processing (memorizing and recalling the word meaning) dominates this kind of learning. Therefore, teachers are suggested to give explanation of the word meanings, assign exercises to the students, and ask them to look up in dictionaries and to think about the meanings.

Table 2.2 Kinds of vocabulary knowledge and the most effective kinds of learning

Use grammar collocation implicit learning repetition

constraints on use explicit learning explicit guidance and feedback

Although the various views on incidental vocabulary learning seem to postulate that it is the most common way of learning new words, some questions remain unanswered. For example: How do the teachers know that the students perform incidental learning? How can

the teachers control students‘ learning? And, how can the teachers be sure that students apply

or do not apply any strategy in such kind of learning? If they do so, what strategy and how learning which in turn results in successful language learning. The following table provides the definitions of learning strategy given by the experts.

Table 2.3 Definitions of learning strategies approach employed by the language learner, leaving techniques as the term to refer to particular forms of observable learning behaviour.‘

‗Learning strategies are the behaviours and thoughts that a learner engages in during learning that are intended to influence the learner‘s encoding process.‘

‗Learning strategies are techniques, approaches or deliberate actions that students take in order to facilitate the learning, recall of both linguistic and content area information.‘

‗Learning strategies are strategies which contribute to the development of the language system which the learner constructs and affect learning directly.‘

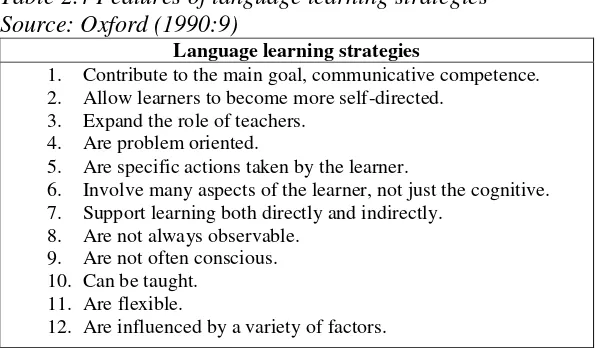

One of the experts, Oxford, identifies the main characteristics of language learning strategies as presented in Table 2.4. It implies that language learning strategies cover various aspects of learning including goals, problems, learners, teachers, and other factors influencing the learning process.

Table 2.4 Features of language learning strategies Source: Oxford (1990:9)

Language learning strategies

1. Contribute to the main goal, communicative competence. 2. Allow learners to become more self-directed.

3. Expand the role of teachers. 4. Are problem oriented.

5. Are specific actions taken by the learner.

6. Involve many aspects of the learner, not just the cognitive. 7. Support learning both directly and indirectly.

8. Are not always observable. 9. Are not often conscious. 10. Can be taught.

11. Are flexible.

12. Are influenced by a variety of factors.

Besides, it also shows that language learning strategies do not only give benefit to the students but also to the teachers, particularly to their role in the teaching-learning process. Their status is now based on the quality and importance of their relationship with students (Oxford, 1990:11). The presence of learning strategies in the process helps them play new roles, namely, as facilitator, helper, consultant, coordinator, adviser, guide, and co-communicator. This encourages them to be more creative in managing the class.

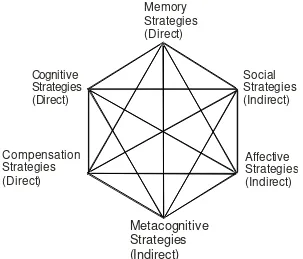

to organize the learning process, affective strategies which are helpful for managing emotions, and social strategies which are beneficial for learning with others.

Memory Strategies (Direct)

Social Strategies (Indirect) Cognitive

Strategies (Direct)

Compensation Strategies (Direct)

Metacognitive Strategies (Indirect)

Affective Strategies (Indirect)

Figure 2.3 The classification of language learning strategies. Source: Oxford (1990:15)

Defining language learning strategies as the processes consciously selected by the learners to enhance their learning or use of L2, Cohen (1998:5) argues that L2 learner strategies cover the strategies for learning and strategies for using L2. According to Cohen, language learning strategies involve the strategies for identifying the learning material, differentiating it from other material, grouping it to make learning easier (for example, grouping vocabulary based on its parts of speech), repeating the contact with the material particularly through classroom tasks or take home assignments, and memorizing the material if it cannot be acquired naturally. In other words the strategies can be applied to cope with material during the learning process. Furthermore, he mentions four subsets of strategies for using the material; (1) retrieval strategies used to recall through memory searching the language material from storage, (2) rehearsal strategies used to practice L2 structures, (3) cover strategies to create impression that they cope the material though they do not, and (4) communication strategies mainly used to convey a meaningful and informative message.

O‘Malley & Chamot (1990:44-45) provide another classification of learning

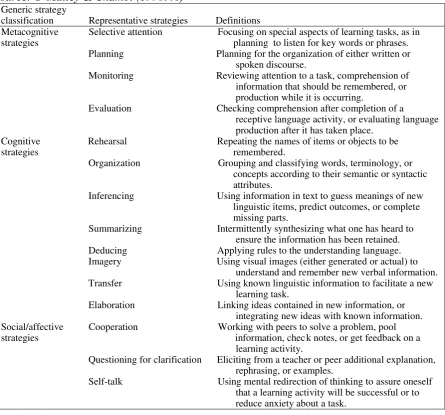

Table 2.5 Classification of learning strategies

This section presents the definitions of vocabulary learning strategy proposed by some experts, continues with the types of the strategy and ends with the most- and least-used strategies found in some studies.

a. Definitions

convincingly important to the success of the vocabulary learning process. Despite the existing research on vocabulary learning strategies, only few researchers have tried to define it. The definition of vocabulary learning strategies is commonly developed from that of language learning strategies which is then expanded to vocabulary learning. Catalan (2003:56) defines vocabulary learning strategy as ‗knowledge about mechanisms (processes, strategies) used in order to learn vocabulary as well as steps or actions taken by students (a) to find out the meaning of unknown words, (b) to retain them in long-term memory, (c) to recall them at will, and (d) to use them in oral or written mode‘. Covering the stages in vocabulary learning, it is likely the most comprehensive one among the existing definitions. Adapting Rubin (1987), Schmitt (1997:203) gives a rather broad definition of vocabulary learning strategy. He describes vocabulary learning strategy as ‗the process by which information is obtained,

stored, retrieved, and used‘. In this sense, ‗use‘ is not meant as interactional communication

but it is defined as vocabulary practice.

Interviewing a number of good language learners, Naiman (1978) identified what they

called ―techniques‖ for L2 learning which are regarded as different from strategies because

their focus in on specific aspects of language learning (O‘Malley & Chamot, 1990:6). They consist of the techniques for sound acquisition, grammar, vocabulary, listening comprehension, and learning to talk, write, and read. Among them, the techniques for vocabulary learning are most frequently used (O‘Malley & Chamot, 1990:7). The techniques include six techniques; (1) making up charts and memorizing them, (2) learning words in context, (3) learning associated words, (4) using new words in phases, (5) using a dictionary when necessary, and (6) carrying a notebook to note new items. These techniques are undoubtedly suitable for learning new words.

strategies to choose, (2) be complex, namely, it has several steps to learn, (3) require knowledge and benefit from training, and (4) increase the efficiency of vocabulary learning and vocabulary use. Because many strategies have such characteristics, it is necessary for the students not only to know the strategies and but also to be skillful in using them.

Ruutmets (2005:8) views a vocabulary learning strategy from three different angles. Firstly, he defines a vocabulary learning strategy as any action taken by the learner to aid the learning process of new vocabulary. This definition is based on the assumption that whenever necessary for a learner to study words, he or she uses a strategy or strategies in doing it. Secondly, a vocabulary learning strategy could be connected to any such actions which improve the efficiency of vocabulary learning. In this sense a vocabulary learning strategy is viewed from its benefit or effectiveness in the learning process. Thirdly, a vocabulary learning strategy might be associated to conscious (as opposed to unconscious) actions taken by the learner in order to study new words. It means that a strategy needs to be consciously employed by the learner. For that reason, it is necessary for the learners to be made aware of good or efficient strategies, so that they can freely and consciously select the ones suitable for them.

b. Types of Vocabulary Learning Strategy