Disability Discrimination Laws

Kathleen Beegle

Wendy A. Stock

a b s t r a c t

We present new evidence on the effects of disability discrimination laws based on variation induced by state-level antidiscrimination measures passed prior to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The evidence expands upon other research that focuses solely on the impact of the ADA by using a ‘‘quasi-experimental’ ’ framework that generates treatment and comparison groups. We nd that disability discrimination laws are associ-ated with lower relative earnings of the disabled, with slightly lower dis-abled relative labor force participation rates, but are not associated with lower relative employment rates for the disabled once we control for pre-existing employment trends among the disabled.

I. Introduction

A large segment of the U.S. population reports some level of disabil-ity related to functional activities or activities in daily living (McNeil 1997; DeLeire 2000). Previous studies have shown that persons with disabilities have lower eco-nomic status and that disability status is strongly associated with reduced labor force participation and wages. Partly in response to the large disparities in labor market outcomes across persons with and without disabilities, the Americans with

Disabil-Kathleen Beegle is an economist at The World Bank, Washington, D.C. Wendy A. Stock is an associate professor of economics at Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana. The authors thank Nico Och-mann and David Rumpel for thorough research assistance. They also thank Douglas Kruse, two anony-mous referees, and seminar participants at the Midwest Economics Association and Southern Econom-ics Association Meetings for helpful comments. These are the views of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank. The authors gratefully acknowledge funding support from National Insti-tute on Aging grant number R03 AG16788-01. The data used in this article can be obtained beginning April 2004 through March 2007 from Kathleen Beegle, MSN MC3-306, 1818 H Street NW, Washing-ton, D.C., 20009.

[Submitted July 2001; accepted May 2002]

ISSN 022-166XÓ2003 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

Beegle and Stock 807

ities Act (ADA) was signed into law by Congress in 1990. A fundamental assumption underlying the ADA is that disabled workers retain low economic status in part due to discrimination in the labor market and lack of access to employment opportunities. The ADA was thus purported to establish, among other things, equal access and opportunity to employment in public and private sectors for persons with disabilities. However, critics counter that the legislation has potentially raised the costs of em-ploying persons with disabilities and may worsen labor market outcomes for disabled persons relative to nondisabled persons. This paper presents new evidence on the effects of disability discrimination laws based on variation induced by state-level antidiscrimination measures passed prior to the ADA. We nd that disability discrim-ination laws are associated with slightly lower labor force participation rates of the disabled, relative to other disabled individuals in states without such laws and con-trolling for changes in outcomes for the nondisabled. We also nd negative effects of the laws on the relative earnings of the disabled. However, once we control for preexisting employment trends among the disabled and nondisabled, we do not nd a negative relationship between disability discrimination laws and the relative em-ployment rates of the disabled.

Previous research has also examined trends in labor market outcomes by disability status, concluding that the ADA resulted in lower employment rates for disabled persons (DeLeire 2000; Acemoglu and Angrist 2001). Kruse and Schur (2002), how-ever, nd both increases and decreases in disabled employment rates associated with the ADA, depending on how disability is dened. A fundamental problem with these and similar studies of public policies with such broad coverage (for example, the Civil Rights Act of 1964) is that because the policy was implemented at the federal level and covers nearly all disabled persons, it is difcult to identify a comparison group of disabled individuals that can be used to control for changes in the relative outcomes of the disabled that are unrelated to the legislation. For example, if the relative employment of disabled workers was falling prior to the passage of the ADA, then estimating the impact of the ADA requires a comparison of the relative employment levels for disabled individuals in the same time period who are and are not covered by the Act, a technique that is unworkable given the ‘‘before and after’’ framework available by focusing solely on the passage and implementation of the ADA.

Another motivation for examining the impact of state-level antidiscrimination ef-forts for the disabled stems from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions that substan-tially limit the scope of the ADA by excluding from coverage those whose conditions can be mitigated by medication or other corrective devices (Sutton v. United Airlines, Inc.U.S. Supreme Court No. 97–1943 1999;Murphy v. United Parcel Service, Inc.

U.S. Supreme Court No. 97–1992 1999). Largely in response to this interpretation of the ADA, some states are revisiting their disability discrimination laws and ex-panding them to explicitly cover workers whose conditions can be mitigated.1Thus, state-level policies may play an increasingly important role in antidiscrimination efforts.

Using data from the 1970– 90 decennial U.S. Censuses of Population, we nd that disability discrimination laws are associated with marginally lower labor force participation rates and lower relative earnings for the disabled, but nd no systematic relationship between the laws and disabled employment rates. Our results are poten-tially more appealing than earlier research that focuses on the impact of the ADA in that they are generated from a quasi-experimental empirical framework and ac-count for the applicable laws, whereas the earlier ‘‘time-series’’ studies of the federal law assume the ADA is the only applicable legislation.

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section provides a background for the research, with a discussion of related studies and an overview of state and federal disability discrimination laws. Section III presents the theoretical and empirical framework for examining and interpreting the effects of the laws. We discuss the data used in Section IV and our empirical results in Section V. The paper concludes in Section VI.

II. Background

People with disabilities are less likely to work and, when employed, earn less than nondisabled workers. Haveman and Wolfe (1990) found that, even with increased transfers from government programs in the 1960s, disabled persons remained economically disadvantaged from 1962 through 1984. Benneeld and McNeil (1989) found lower labor market attachment of disabled workers relative to the nondisabled and, on average, a reduction in the relative earnings of disabled men and women over the period 1980– 87. Yelin and Katz (1994) found that over the period 1970– 92, trends in labor force participation rates of persons with disabilities

Beegle and Stock 809

closely followed those of nondisabled persons of the same age and sex. Despite a multitude of programs targeted toward disabled workers, their labor market position had not improved relative to the nondisabled by the 1990s (McNeil 1993).

Although the disadvantaged relative economic position of disabled persons is well established, it is much less clear what role various factors play in propelling this outcome. Persons with disabilities obviously have health problems that can poten-tially limit their productivity and thus impact their employment status. In addition, the disabled may also face lower wage and employment levels due to employer prejudice or statistical discrimination. Earlier work has attempted to distinguish be-tween these competing effects. The estimates from these studies vary widely, with some nding that discrimination accounts for between 30 and 50 percent of the wage differential between disabled and nondisabled workers and also induces lower labor force participation among the disabled (Johnson and Lambrinos 1985; Baldwin and Johnson 1994; Baldwin and Johnson 1995). Alternatively, DeLeire (2001) nds that during the period 1984– 93, only 3.7 percent of the earnings differential was due to discrimination. Nonetheless, legislation protecting the disabled was enacted at least in part on the premise that disabled people faced discrimination in the labor market [see, for example, National Council on Disability (NCD) 1997].

existing trends in labor market outcomes among the disabled and nondisabled. By focusing on state-level variation in the timing of laws, our control group is effectively persons from other states in the same time period, which eliminates the impact of time or group effects that are common across states.

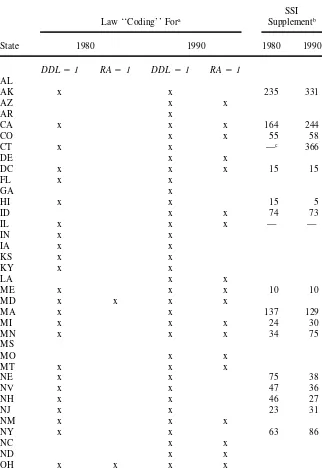

Table 1 documents the evolution of state-level legislation regarding disability dis-crimination as identied from several sources. Based on Table 1, Table 2 presents our ‘‘coding’’ of the state laws into dummy variables that we use in the regression analysis below. Because no state had a disability discrimination law covering the private sector by 1970, Table 2 only includes disability discrimination laws in place by 1980 and 1990. For each state, we list in Table 1 the year legislation was enacted, the type of handicap covered by the state’s statutes (physical, mental, or other handi-cap), whether the statute includes a reasonable accommodation provision, the sector covered (private or public), the statute number (where applicable), and the sources of the information. For example, in 1973 Arkansas (AR) passed an antidiscrimination law covering the disabled in public-sector employment (originally §82-2902 and later changed to §20-14-301). Sales et al. (1982) document that there existed no antidiscrimination coverage for the disabled in the private sector by 1982. Burgdorf (1995), however, reports that §20-14-303 covered the physically and mentally handi-capped in the public and private sectors in Arkansas in 1987. Thus, in Table 2, Arkansas is coded as having its disability discrimination law (DDL) equal to 0 in 1980 and equal to 1 in 1990.

Antidiscrimination provisions for disabled persons were in large part developed from earlier civil rights or fair employment practices legislation that initially covered such characteristics as race, sex and age. In many states, the predecessors to these laws were ‘‘White Cane’’ provisions and similar laws passed in the late 1960s and early 1970s that provided public sector employment protection to blind persons and others with physical disabilities (and, of course, legally established the white cane as a symbol of vision impairment). Subsequent to these White Cane laws, most states either amended their existing antidiscrimination statutes (such as Fair Employment Practices or Human Rights Acts) to expand coverage to the disabled, expanded ex-isting employment protection for the disabled to include the private sector, or initi-ated original disability discrimination laws.

As shown in Table 1, disability discrimination laws vary widely across states with respect to their coverage of physical and mental disabilities (although no state ever covered only mental disability and excluded physical disability), their application to private sector employment, and their requirements for reasonable accommodation by employers (with over half of states having some requirement by 1990). Moreover, they also vary according to the breadth of their enforcement and their establishment of stipulated penalties. Several studies detail the nuances across the state laws with respect to antidiscrimination for the disabled in the realm of employment and other areas (see, among others, Sales et al. 1982; Flaccus 1986; Goldman 1987; Advisory Committee on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR) 1989; and Burgdorf 1995).

man-B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

Table 1

State-Level Disability Discrimination Laws

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

AL

1975 PH PU §21-7-8 Text of statute No private sector coverage before

—d Sales et al. (1982) 1982

— PH PU §21-7-1 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU §21-7-8 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

AK

1978 PH PU MLRe(1979) PH given employment preference

without examination

1980 PH PU MLR (1981) Coverage already exists for private

sector

1987 MH MLR (1988) Extend discrimination prohibition to

MH in addition to PH

— PH §18.80.220 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU §18.47.080 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §18.80.220 ACIR (1989); text of

statute

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

AZ

1985 PH, RA PU, PR MLR (1986);

Burg-dorf (1995)

1986 PH PU, PR §41-1463 Text of statute

— PH §41-1463 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §41-1463 ACIR (1989)

— MH PU, PR §36-506 ACIR (1989)

AR

1973 PH PU §20-14-301 Text of statute Was §82–2902

— Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

— PH PU §82-2902 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

1987 PH, MH PU, PR §20-14-303 Burgdorf (1995)

— PH PU §20-14-301 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

CA

1973 PH PR Labor Code 1420 MLR (1974); Text

of statute

1975 Rehab/cured of MLR (1976)

cancer

1976 Color blindness/ PU MLR (1977)

weakness

1976 PH State MLR (1977)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

k

1978 PH PR Labor Code 1420 Sales et al. (1982)

1980 PH, RA PU, PR §12940-12996 Flaccus (1986)

1984 Alcohol rehab. PU, PR MLR (1985)

— PH §12940 Goldman (1987);

Text of statute

— PH PU, PR §12940 ACIR (1989); Text

of statute

— PH §54.5 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

CO

1974 PH PU §24-34-801 Sales et al. (1982) Public only

1975 Developmentally MLR (1976) Prohibit employment discrimination

Disabled if developmentally disabled can

meet standards set for others

1979 PH PU §24-34-801 Text of statute

1982 PH, RA PU, PR §24-34-402(1)(a) Flaccus (1986)

&§24-34-301 to -802

— PH §24-34-402 Goldman (1987)

— PH §24-34-801 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

1989 PH, MH MLR (1990) Expand coverage from PH to MH

and PH

— PH PU, PR §24-34-402 ACIR (1989); Text

of statute

— PH §24-34-801 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

CT

1973 PH PU, PR MLR (1974)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

DE

1979 PH MLR (1980) State human rights commission can

act as conciliator

— Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

1986 Flaccus (1986) No private sector coverage before

1986

1988 PH, MH, RA PU, PR Title 19 sec. 721 MLR (1989); Text 201Employees; coverage under of statute Handicapped Persons Employment

Protection Act enforcement in De-partment of Labor

— PH PU Title 16 sec. ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

9501

DC

1973 PH PR §6-1504 Sales et al. (1982)

1974 PH MLR (1975)

1981 PH, RA PU, PR §1-2501 to -2557 Flaccus (1986)

— PH §1-2512 Goldman (1987)

— PH §6-1504 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH PU, PR §1-2512 ACIR (1989)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

FL

1973 PH PU §413.20 MLR (1974); Text

of statute

1974 PH PU, PR MLR (1975) Constitutional amendment to prohibit

discrimination; also establishes penalties for PU employers

1978 PH PR §413.08(3) Sales et al. (1982)

1984 PH PU MLR (1985)

— PH PU, PR §760.10 ACIR (1989); Text

of statute

— PH PU §413.20 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

— PH PU, PR §760.10 Goldman (1987);

Text of statute

— PH §413.08 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

GA

1978 PH PU §45-19-21 MLR (1979); Text Has enforcement authority

of statute

1980 Deaf PU MLR (1981) Coverage for blind already exists;

FEPA for PH already exists

1981 PH PU, PR §36-6A-4 Text of statute

1981 PH PU, PR MLR (1982)

— Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

— PH §45-19-22 Goldman (1987)

— §34-6A-1 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §36-6A-4 ACIR (1989)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

HI

1975 PH PU, PR §378-2 MLR (1976); Text

of statute

1976 PH PR §378-2 Sales et al. (1982)

— PH §21-378 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §21-378 ACIR (1989)

ID

1969 PH PU §56-707 Text of statute

— Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

— PH PU §56-7 Goldman (1987)

1988 PH, MH, RA PU, PR Title 57 Ch. 59 MLR (1989); Burg- Amendment to Idaho HRA §5901 to -5912 dorf (1995)

— PH PU §56-707 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

IL

1971 PH PU, PR MLR (1972)

1975 PH PU, PR §68-2-102 MLR (1976); Text 151Employees (was 251

em-of statute ployees)

Originally FEPA, changed to HRA in 1980

1975 PH PU, PR §68-1-101 to 9- Flaccus (1986)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

1984 RA PU, PR 453:2742-43 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §68-2-102 Goldman (1987)

— §23-3363 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH PU, PR §68-2-102 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §23-3363 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

IN

1969 PH PU §16-7-5-6 Text of statute

1975 PH PU, PR §22-9-1-2 MLR (1976); Text

of statute

— PH, MH §22-9-3-1 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §4-15-12-2 ACIR (1989)

— PH, MH PU §16-7-5-6 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

IA

1972 PH MLR (1973) Law to prohibit employment

discrim-ination against handicapped

1975 PH PU, PR §601A.6 Sales et al. (1982);

Text of statute

— PH, MH PU, PR §601A.6 & Goldman (1987);

§216.6 Text of statute

— PH PU §601D.2 & Goldman (1987); White Cane Law

§216C.2 Text of statute

— PH, MH PU, PR §601A.6 ACIR (1989)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

KS

1969 PH PU §39-1005 Text of statute

1973–75 PH PR §44-1009(a)(b) Sales et al. (1982)

1974 PH PU, PR MLR (1975)

1978 PH PU MLR (1979) Applies to personnel actions; except

when a physical ability constitutes a bona-de occupational quali-cation

— PH PU, PR §44-1009 Goldman (1987);

Text of statute

— PH PU, PR §44-1009 ACIR (1989); Text

of statute

— PH PU §39-1105 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

KY

1976 PH PU, PR §207.150 MLR (1977); Text 81employees; has enforcement

of statute

1978 PH PR §201.150 Sales et al. (1982)

— PH §207.150 Goldman (1987)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

LA

1975 PH PU §46:1951 Text of statute

1978 Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1978

1980 PH PU, PR §46:2254 MLR (1981); Text CRA for handicapped

of statute

1982 RA PU, PR §46:2254(c)(1) Flaccus (1986)

1985 MH PU, PR MLR (1986) CRA for handicapped expanded to

include MH

— PH, MH §46-2254 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §46-2254 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §46-1951 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

ME

1971 PH PU §17-1316 MLR (1972); Text

of statute

1974 PH MLR (1975)

1975 PH, MH PU, PR §5-4572 and MLR (1976); Text Claried language of HRA to

explic-§5-784 of statute itly cover PH and MH

1978 PH PU, PR §5-4572 Sales et al. (1982)

1980 RA PU, PR 8A:455:534 Flaccus (1986)

1985 PH, MH PU MLR (1986) Extended discrimination prohibitions

to cover PH and MH

— PH, MH §5-4571 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §5-4572 and ACIR (1989)

§5-783

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

MD

1966 PH PU Art. 30-33 Text of statute

1972–78 PH PR §49B-19 Sales et al. (1982)

1974 PH MLR (1975)

1978 PH MLR (1979) Employer cannot ask applicants

about disability if it is not related to job requirements

1979 RA PR Tit. 14.02 §05(B) Flaccus (1986)

1981 PH PU MLR (1982) Teachers only

— PH, MH §49B-16 Goldman (1987);

Text of statute

— §30-23 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH PU, PR §49B-16 ACIR (1989); Text

of statute

— PH PU §30-33 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

MA

1972 PH MLR (1973) Law to remove employment

discrimi-nation against handicapped

1973 PH MLR (1974) Prohibit employment discrimination

against handicapped unless handi-cap is a deterrent to work

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

1980 PH PU, PR MLR (1981) Amended state constitution to

pro-hibit discrimination against handi-capped

1984 PH PU, PR MLR (1985) Amended FEPA to include

discrimi-nation against handicapped; Com-mission Against Discrimination as administrative agency

— PH, MH §151B-4 Goldman (1987);

text of statute

— PH, MH PU, PR §151B-4 ACIR (1989); Text

of statute

MI

1976 PH PU, PR §37.1202 MLR (1977); Text

of statute

1978 PH PR §37.1202 Sales et al. (1982)

1980 PH PU, PR MLR (1981) FEPA coverage extended to all

em-ployers; was 41employees

1981 PH, MH PU, PR MLR (1982) Extension of coverage of CRA to

previously mentally ill; already ex-isted in general

1985 RA PR §37.1102 (2) Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §37.1202 Goldman (1987)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

MN

1973 PH MLR (1974) Prohibit employment discrimination

against PH unless a deterrent to work; allows medical exam and medical history investigation

1978 PH PU, PR §363.03 Sales et al. (1982);

Text of statute

1983 RA PU, PR §363.03(6) Flaccus (1986); Text

of statute

1983 PH PU, PR MLR (1984) 501employees

1987 PH PU, PR MLR (1988) Accommodation in excess of $50 no

longer considered undue hardship under HRA; 501employees

— PH, MH §363.03 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §363.06 ACIR (1989)

MS

1974 PH PU MLR (1975) No enforcement

1978 Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1978

1984 PH PU §25-9-149 MLR (1985; Text of

statute

— PH PU §25-9-149 Goldman (1987)

— PH §43-6-15 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH PU §25-9-149 ACIR (1989)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

MO

1977 PH PU §209.180 Text of statute

1978 PH MLR (1979) Prohibits discrimination based on

dis-ability that is not job related

1982 Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

1986 PH PU, PR §213.055 Text of statute

1986 RA PR 8A:§455:1605 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §213.055 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §213.055 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §209.180 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

MT

1970–77 PH PR §64-306 Sales et al. (1982)

1974 PH §49-2-303 and MLR (1975); Text

§49-4-101 of statute

1975 PH PU MLR (1976) FEPA enforcement transferred to

hu-man rights commission

1984 PH PU MLR (1985) Preference in hiring for PH

1986 RA PR Ad. R.24.9.1404 Flaccus (1986);

Burgdorf (1995)

— §9-4-202 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH §49-2-303 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §49-2-303 and ACIR (1989)

§49-4-101

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

NE

1971 PH PU §20-131 MLR (1972); text of

statute

1973 PH PU, PR §48-1104 MLR (1974); text of

statute

1974 PH PR §48-1104 Sales et al. (1982)

1978 PH MLR (1979) Cities and villages can ban

discrimi-nation based on disability

1979 PH PU MLR (1980) FEPA as source for lawsuits

— PH, MH §48-1101 Goldman (1987)

1989 MLR (1990) FEPA redened to exclude current

al-cohol/drug/gambling addiction

— PH, MH PU, PR §48-1104 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §20-131 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

NV

1973 PH PR §613.330 Sales et al. (1982)

1973 PH MLR (1974)

1981 Deaf MLR (1982) Already coverage for blind, physical

handicap and ‘‘other bases’’

1985 PH PU MLR (1986)

— PH §613.330 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §613.330 ACIR (1989); text of

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

NH

1971 PH PU §167-C:5 Text of statute

1975 PH MLR (1976)

1977 PH PR §354-A:8 Sales et al. (1982)

— PH, MH §354-A Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §354-A:7 ACIR (1989); text of

statute

— PH PU §167-C:5 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

NJ

1972 PH PU, PR §10:5-4.1 MLR (1973); text of

statute.

1976–78 PH PR §10-5-4.1 Sales et al. (1982)

1978 Blind MLR (1979) Unlawful employment practice to

deny blind a job unless related to job performance ability

— PH, MH §10:5 Goldman (1987)

— §10:5:29 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH PU, PR §10:5-4.1 ACIR (1989)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

NM

1967 PH PU §28-7-7 Text of statute

1973 PH MLR (1974)

1974–75 PH PR §4-33-7(a-e) Sales et al. (1982).

1983 PH, MH, RA PR §28-1-7 J MLR (1984); Flac- HRA makes it discriminatory to

re-cus (1986) fuse or fail to accommodate PH or MH unless imposes unreasonable or undue hardship

— PH, MH §28-1-7 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §28-1-7 ACIR (1989); text of

statute

— PH PU §28-7-7 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

NY

1972–77 PH PR §296 (1,1a) Sales et al. (1982)

1974 PH PU, PR Exec Law 296 MLR (1974); text of

statute

1976 Blind PU, PR MLR (1977)

1976 PH PU §47-a text of statute

1979 PH MLR (1980) Criterion for assessing disability

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

1982 PH PR MLR (1983) 41Employees

1986 PH MLR (1987) Expanded coverage from blind and

deaf with dog to PH w/dog

— §47-a Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH Exec Law 296 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR Exec Law 296 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §47-a ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

NC

1976 PH PU §168-6 Sales et al. (1982); Statute covers public

accommoda-text of statute tions not employment

1985 PH PU, PR §168A-5 MLR (1986); text of 151employees; enforcement

statute through civil action

1985 RA PR §168A-4(b) Burgdorf (1995);

text of statute

— PH, MH §168A-5 and Goldman (1987)

§143-422.2

— PH, MH PU, PR §168A-5 ACIR (1989)

— PH, MH PU §126-16 ACIR (1989); text of

statute

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

ND

— Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

1983 PH, MH PU, PR MLR (1984) HRA enacted to prohibit disc on

ba-sis of PH or MH; 101employees; repeals or replaces state policy declaration applying to 151 em-ployees

— PH, MH §14-02.4 Goldman (1987)

1989 PH, RA PR, PR §14-02.4-01 MLR (1990); Burg- Amended to include reasonable

ac-dorf (1995); text commodation of statute

— PH, MH PU, PR §14-02.4 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU, PR §25-13-05 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

OH

1973–77 PH PR §4112.02 (A-F) Sales et al. (1982)

1976 PH PU, PR §41.4112 MLR (1977); text of 41employees

statute

1977 PH State §153.59 Text of statute

contractors

1978 RA PR 8A: 457:270a-b Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §41.4112 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §41.4112 ACIR (1989)

— PH State §153.59 ACIR (1989)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

OK

1981 PH PU, PR §25-1302 MLR (1982); text of

statute

1982 PH PU MLR (1983)

— PH, MH §25-1301 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §25-1302 ACIR (1989)

OR

1973 PH PR §659.425(1) Sales et al. (1982);

MLR (1974)

1975 State MLR (1976) Public contractors encouraged to

contractors reach afrmative action goals

1979 PH MLR (1980) Coverage expanded to unions and

employment agencies

1983 RA PR §659.425 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §659.400 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §659.400 ACIR (1989)

PA

1978–79 PH PU, PR §43.955 Sales et al. (1982);

text of statute

1978 RA PR 8A:457:867 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §43.955 Goldman (1987)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

RI

1973 PH MLR (1974)

1977 PH PU, PR §28-5-7 Sales et al. (1982);

text of statute

1981 MH MLR (1982) Adds MH to existing PH disc

prohi-bition

1983 PH PU, PR MLR (1984) Adds chapter to state affairs and

gov-ernment law; applies to any per-son or entity doing business in state; is in addition to earlier FEPA for PU and PR

1983 PH PU, PR §22-87-2 Text of statute

1986 RA §28-5-1 MLR (1987); Burg- FEPA amended to include

reason-dorf (1995) able accommodation

— PH, MH §28-5-7 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §28-5-7 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §40-9.1-1 ACIR (1989); text of White Cane Law

statute

SC

1976 Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1976

1983 PH MLR (1984) Bill of Rights for handicapped;

Hu-man Affairs Commission as admin-istrative agency

— PH, MH §43-33-530 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §43-33-530 ACIR (1989)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

SD

1973 PH PU §3-6A-15 Text of statute

1977 Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1977

1980 PH State MLR (1981) Preference in contracting for rms

contractors w/deaf (already exists for rms

w/blind)

1984 Blind PU, PR MLR (1985) Prohibited under state HRA

1985 RA PU, PR §20-13 Burgdorf (1995);

text of statute

1986 PH PU, PR MLR (1987) Coverage under Human Relations

Act

— PH, MH §20-13-10 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §20-13-10 ACIR (1989)

— PH PU §3-6A-15 ACIR (1989)

TN

1976 PH PU, PR §8-50-103 MLR (1977); text of No administrative agency named for

statute enforcement for private sector

1977 PH PR §8-4131 Sales et al. (1982)

1979 Blind MLR (1980)

1979 PH MLR (1980) Established procedure to le

disabil-ity discrimination complaints with state human development commis-sion

1981 PH PU MLR (1982) Testing accommodation allowed for

applicants for state employment

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

TX

1975 PH, MH PU, PR §4419e(3)(f ) MLR (1976); text of

statute

1976 PH PR §4419e(3)(f ) Sales et al. (1982)

1979 PH PU §121.003 Text of statute

1981 PH PU, PR MLR (1982) Alternative forms of testing PH job

applicants allowed

1983 PH PR MLR (1984) 151employees; administered by

Commission on HR

1983 PH, MH, RA PU, PR §5221(K) Flaccus (1986); text

§6.01(d) of statute

— PH, MH §121.003 Goldman (1987)

— §5547-300 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU §121.003 ACIR (1989) White Cane Law

— PH, MH PU, PR §5521K ACIR (1989)

— MH PU, PR §5547-300 ACIR (1989)

UT

1979 PH PU, PR §34-35-1 MLR (1980); text of

statute

— PH, MH §34-35-1 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §34-32-6 ACIR (1989)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

VT

1972 MLR (1973) Policy declaration to remove

employ-ment discrimination against handi-capped

1974 PH MLR (1975) Discrimination against PH unlawful

employment practice. Enforceable by civil action or complainant

1978 PH PR §21.498 Sales et al. (1982)

1981 PH MLR (1982) ADL amended to prohibit disc based

on PH or MH; an earlier provision protecting PH only was repealed

1985 RA PR §21.495(d) Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §21.494 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §21.495 ACIR (1989)

VA

1975 PH PU, PR MLR (1976) Prohibited all employers from

dis-crimination against handicapped

1976 PH PR §40.1-28.7 Sales et al. (1982)

1985 RA PR §51.01-41.C Flaccus (1986)

1987 PH PU, PR MLR (1988) HRA-enacted; conduct violating

state law, Title VII, or Federal FLSA unlawful; enforcement un-der Council on Human Rights

— PH, MH §51.01-41 Goldman (1987)

— §2.1-716 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §51.01-41 ACIR (1989)

T

h

e

Journal

of

H

um

an

R

es

ourc

es

Table 1 (continued)

Handicap Sector

State/Year Covereda Coveredb Statute/Code/Law Source Otherc

WA

1969 PH PU §70.84.080 Text of statute

1973 PH MLR (1974)

1977 PH, MH PU, PR §49.60.180-200 Sales et al. (1982);

text of statute

1979 RA PR 8A:457:3069-70 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §49.60.180 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §49.60.180 ACIR (1989)

WV

1969 Blind PU §5-15-7 Text of statute

1978 PH PU, PR §5-11-9(a-e) Sales et al. (1982);

text of statute

1981 PH MLR (1982) HRA amended to prohibit disc on

ba-sis of handicap; already existed for blind

1982 RA PR 8A:457:3069-70 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §5-11-9 Goldman (1987)

— §5-15-4 Goldman (1987) White Cane Law

— PH, MH PU, PR §5-11-9 ACIR (1989)

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

WI

1973–79 PH PR §111.32 Sales et al. (1982)

1976 PH PU, PR MLR (1977) Unfair labor practices enumerated

1976 PH, develop- State MLR (1977) State contractors must take

afrma-mental dis- contractors tive action to employ the disabled

ability

1982 PH, MH MLR (1983) FEPA amended to dene handicap

as including MH or PH

1985 RA PR §111.34 Flaccus (1986)

— PH, MH §111.321 Goldman (1987)

— PH, MH PU, PR §111.31 ACIR (1989)

WY

— Sales et al. (1982) No private sector coverage before

1982

1985 PH, RA PU, PR §27-9 MLR (1986); Burg- Coverage under FEPA

dorf (1995); text of statute

— §27-9-101 Goldman (1987)

— PH PU, PR §27-9-105 ACIR (1989)

a. PH5disabled/physical handicap; MH5mental handicap; RA5reasonable accommodation clause in statute.

b. PU5public sector covered; PR5private sector covered.

c. HRA5Human Rights Act; CRA5Civil Rights Act; FEPA5Fair Employment Practices Act.

d. Year of the legislation is not reported by the source.

Table 2

State Disability Discrimination and Equal Opportunity Laws Covering Private-Sector Workers and SSI payments

SSI

Law ‘‘Coding’’ Fora Supplementb

State 1980 1990 1980 1990

DDL51 RA51 DDL51 RA51

AL

AK x x 235 331

AZ x x

AR x

CA x x x 164 244

CO x x 55 58

CT x x —c 366

DE x x

DC x x x 15 15

FL x x

GA x

HI x x 15 5

ID x x 74 73

IL x x x — —

IN x x

IA x x

KS x x

KY x x

LA x x

ME x x x 10 10

MD x x x x

MA x x 137 129

MI x x x 24 30

MN x x x 34 75

MS

MO x x

MT x x x

NE x x 75 38

NV x x 47 36

NH x x 46 27

NJ x x 23 31

NM x x x

NY x x 63 86

NC x x

ND x x

Beegle and Stock 837

Table 2 (continued)

SSI

Law ‘‘Coding’’ Fora Supplementb

State 1980 1990 1980 1990

DDL51 RA51 DDL51 RA51

OK x 79 64

OR x x x 12 2

PA x x x x 32 32

RI x x 42 64

SC x

SD x x 15 15

TN x x

TX x x x

UT x x 10 6

VT x x x 41 63

VA x x x

WA x x x x 43 28

WV x x

WI x x x 100 103

WY x x 20 20

Source: State statutes and references in: Monthly Labor Reviews (1970– 1990); Burgdorf (1995); ACIR (1989); Goldman (1987); Flaccus (1986); Sales et al. (1982). See Table 1 for complete details. 1970 is not included because no state had a law covering the private sector by 1970.

a. DDL: state has disability discrimination law covering private sector by census decade; RA: state disabil-ity discrimination law includes a reasonable accommodation clause. ‘‘x’’ indicates DDL (RA) coded as 1 for state/year, otherwise DDL (RA) is coded as 0.

b. Columns report monthly values of state supplements to the Federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payments. Source: Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives (1996).

c. Connecticut and Illinois decided their supplements to SSI on a case-by-case basis, and awarded supple-ments to SSI only in certain cases.

who are presumed to be unable to work, and toward the establishment of antidiscrim-ination rights and accommodations needed for access to jobs to which disabled per-sons are qualied (NCD 1997; Yelin 1997). In some sense as a capstone to this trend, in July 1990, Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which established access to public and private employment. The ADA also mandates the provision of reasonable accommodation of disabilities by employers that encom-passes both physical barriers to facilities as well as job restructuring with respect to the scheduling, pace, or ow of work.

There are at least two reasons why the implementation of the ADA did not render the state laws obsolete. First, as the ADA does not preempt state law that offers greater protection, covered entities must comply with the more stringent law in their respective state (Burgdorf 1995). For example, as of July 1994, the ADA applied to all businesses with 15 or more employees, but 34 states had statutes that extended coverage for businesses with fewer than 15 employees. Thus, even with federal pro-tections in place, individuals may still seek protection via their respective state’s statutes.2

Second, although the ADA denes ‘‘disability’’ in very broad terms to mean, ‘‘with respect to an individual— (A) a physical or mental impairment that substan-tially limits one or more of the major life activities of such individual; (B) a record of such an impairment; or (C) being regarded as having such an impairment’’ (ADA 1990, Sec. 3(2)), its scope has recently been limited by the U.S. Supreme Court. In a 1999 decision, the Court held that ‘‘those whose impairments are largely corrected by medication or other devices are not ‘‘disabled’’ within the meaning of the ADA’’ (Sutton v. United Airlines, Inc.,U.S. Supreme Court No. 97–1943 1999). In response, some states (for example, Rhode Island) are reformulating their disability discrimina-tion laws to explicitly cover this group. As a result, state-level legisladiscrimina-tion may play an increasingly important role in determining outcomes for disabled individuals.

III. Theoretical and Empirical Framework

for Examining Discrimination Laws

The theoretical impacts of disability laws on the labor market have previously been modeled (Acemoglu and Angrist 2001) and we only briey summa-rize the theory here. The laws’ impacts are most easily analyzed by focusing on three separate aspects of the laws: nondiscrimination in hiring and ring, nondiscrim-ination in wages, and laws mandating reasonable accommodation on the part of employers. First, regulations that require nondiscrimination in hiring and ring im-pose costs on rms due to an increased risk of lawsuits. Nondiscrimination in hiring

Beegle and Stock 839

effectively provides a subsidy to hiring disabled workers, since not hiring a disabled worker increases the risk of a costly lawsuit for the rm. As a result, such laws should be associated with increased demand and increased employment for disabled workers.3

Alternatively, regulations requiring nondiscrimination in ring raise the costs of hiring disabled workers (by raising the risk of suit associated with ring that particu-lar class of worker), and would be likely to decrease demand and employment of the disabled. If the perceived penalties for not hiring disabled workers are relatively larger than the rm’s (discounted) costs of ring disabled workers, the net effect would be increased demand and employment of disabled workers. Empirically, most lawsuits brought under the ADA have been for wrongful termination, rather than for discrimination in hiring (Mudrick 1997; DeLeire 2000), implying that the rm’s perceived costs of ring would be higher than for not hiring, with the net result that demand and employment would decrease.

Second, if the productivity of disabled workers is lower than that of nondisabled workers (or if rms have discriminatory tastes or statistically discriminate against disabled workers), laws mandating equal pay for disabled and nondisabled workers in the same job would increase the relative cost of disabled workers. If disabled and nondisabled workers are equally productive substitutes and assuming that there is adequate supply of nondisabled labor at the prevailing wage, such laws would imply that the demand for disabled workers would fall to zero as rms choose only to employ cheaper, nondisabled labor. Even if the two types of labor are not equally productive, as long as the elasticity of substitution between disabled and nondisabled workers is positive (implying that an increase in the price of one type of labor is associated with an increase in the demand for the other type of labor), employment of disabled workers would fall as rms substitute nondisabled for disabled workers in the face of higher disabled-worker costs. Similarly, depending on their technology and relative input prices, rms may also substitute toward increased use of capital in response to relative wage increases.

Finally, regulations requiring reasonable accommodation on the part of employers also make it more costly to employ disabled workers. The disabled worker must not only be paid his wage, but must also be provided a potentially costly accommodation that the rm would not have provided in the absence of legislation, resulting in a decrease in the relative demand for disabled workers. If laws also restrict the ability of rms to cut wages in response to the increased worker cost, this would imply further decreases in demand. However, these negative employment effects may be somewhat offset if reasonable accommodation requirements (or other favorable labor market conditions for disabled workers) induce an increase in the supply of disabled workers. In the face of constrained wages, however, this increase in supply may simply result in increased unemployment. The extent to which accommodation af-fects employment will depend on the costs of accommodation and these costs are

difcult to estimate considering their nonmonetary aspects such as exibility in the schedule and pattern of work.4

In sum, the theoretical predictions of the impact of disability discrimination laws imply that the laws should be associated with decreased demand for disabled workers and decreased employment rates. Although all else equal, the reduction in demand (or increase in supply) would imply a reduction in earnings, the wage restrictions of disability laws may stie the negative earnings effect.5

Obviously, the actual impact of these laws will also depend on other characteristics of the labor market for several reasons. First, given the degree of heterogeneity in labor markets, disabled workers may select into occupations or sectors where their disability does not have much impact on productivity or in which disabled persons have traditionally not been discriminated against. In this case, the impact of legisla-tion will be muted as disabled persons are least likely to be in sectors in which legislation would theoretically have the largest impact on outcomes. Second, the impact of laws, even with enforcement mechanisms in place, may evolve over time from the date of passage. If employers are uncertain of the ramications of noncom-pliance or if disabled employees are unaware of the process of pursuing complaints against employers, laws may have an impact only several years after their enactment. On the other hand, uncertainty could lead employers to react more severely initially. Third, trends in the availability of nonlabor transfer income will inuence the labor force participation rates of disabled workers. For example, the enactment of the ADA coincided with a general expansion in the number of people receiving payments from the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Disability Insurance (DI) programs in the early 1990s and a drop in denial rates starting in 1988 (Acemoglu and Angrist 2001; Stapleton et al. 1998).6

Our empirical analysis is designed to assess the labor force participation, employ-ment, and earnings effects of disability legislation for disabled and nondisabled workers using the data described below. Following the theoretical framework de-scribed above, we compute regressions of employment outcomes that identify the net impact of disability laws for disabled workers using a

difference-in-difference-4. The Job Accommodation Network (JAN) reports on the costs of accommodation, estimating the median cost per accommodation at $500.00 or less, and the average cost at $920.00 (JAN 1999). As noted by DeLeire (2000), however, the actual cost of mandated accommodations would likely be higher than these gures indicate, since the JAN report includes accommodations that resulted in zero out-of-pocket costs for employers (for example, allowing a disabled employee a more exible schedule) and would likely have been undertaken voluntarily by rms. Accommodations that rms are less likely to make voluntarily are more likely to be those that are more expensive.

5. As noted by Acemoglu and Angrist (2001), assumptions about the ease of entry and exit for rms in the market may change these straightforward predictions. If the number of rms in the industry is xed, increased costs of not hiring disabled workers may increase employment of disabled workers, while if there is free entry and exit by rms, rms at the margin will exit the market in response to increased costs of nonhiring, resulting in decreased employment of the disabled. In either case, ring costs imply decreased employment of disabled workers. Because we note above that rms are likely to perceive ring costs as relatively higher than costs of not hiring disabled workers, we conclude negative employment effects in either case.

Beegle and Stock 841

in-difference approach. This type of assessment can be done using regressions of the basic form:

(1) Yist5a1Xistb1(DDLst*DISist)g1DISistq1DDLstj1Ssbs1Ttbt1eist

whereYistindicates an outcome (alternately labor force participation, employment, and the log of annual earnings) of individual iin states in yeart.

In Equation 1,Xis a vector of standard demographic controls (age and its square and indicators for female, black, white, residence in an SMSA, educational attain-ment, and marital status),DISis an indicator of disability status, andDDLis a dummy variable indicating the presence of a disability discrimination law in statesat time

t. (In the earnings regressions, we also include industry and occupation dummies and weeks and hours worked controls.)Trepresents a set of year dummy variables andS is a set of state dummy variables. Thus, the coefcients bs andbt identify

differences inYacross states (for all years) and across time (for all states) for all individuals. With this specication, we are able to evaluate the net impact of disabil-ity discrimination laws on disabled workers, differencing out changes in outcomes among disabled workers in states with and without laws and similar changes for nondisabled workers in these states. The coefcient gisolates this difference-in-difference-in-difference estimator.7,8

In some specications, we also include interactions between state and year to allow for common, xed effects for observations in the same state and year that are not persistent across years or states. Because such interactions are dened by state and year, however, including them prevents estimation ofj, since the interactions generate a common intercept shift for all observations in a state and year (and would thus be perfectly collinear withDDL). In addition, we also include interactions be-tween disabled and state and disabled and year to allow for separate shifts inYfor the disabled in different states, and particularly, for a separate time trend inYfor the disabled. This specication is shown in Equation 2:

(2) Yist5a1Xistb1(DDLst*DISist)g1DISistq 1(Ss*DISist)rs

1(Tt*DISist)rt1Ssbs1Ttbt1(Ss*Tt)bst1eist

We also report other modications to the basic specication. First, because it is likely that individuals of different ages had different trends in labor market outcomes over the period, in some specications we also include a vector of age group dummy by year dummy interactions to capture differences in trends in outcomes by age group. Second, as noted above, nonlabor income changes may affect the labor force participation, employment, and earnings outcomes for the disabled. In some

cations, therefore, we include an interaction between disabled and a dummy indicat-ing whether the individual’s state supplements the federal SSI payments to the dis-abled. Over the last 25 years, roughly half of the states have chosen to provide optional state supplementary payments to the federal SSI payments, as summarized in Table 2 (Committee On Ways and Means 1996). Third, another important aspect of many of these laws is their provision requiring reasonable accommodation by employers. To capture the incremental effect of this requirement, we also introduce an interaction between disabled (DIS) and the presence of a reasonable accommoda-tion clause in the individual’s respective state statute (RA).9

Finally, as noted above, Acemoglu and Angrist (2001) found the most signicant effects of disability laws for males and for younger females. Thus, we also estimate the models separately for older and younger individuals. In addition, we estimate the models separately by sex and race, since other laws barring discrimination based on race and sex may have also played a role in outcomes across these groups.

It is important to note some caveats to the empirical strategy. First, the passage of a state disability discrimination law is not a random outcome but instead may be endogenous. This raises the concern that some ‘‘sorts’’ of states were predisposed to enact legislation to protect disabled citizens and their employment opportunities. Holbrook and Percy (1992) explore the status of state disability rights laws as of 1989 and their correlation to variables traditionally successful at explaining other types of state policies. They nd that these variables are generally much less success-ful at explaining the status of disability rights laws and that an explanation of differ-ences in these laws across states requires other, less orthodox approaches such as understanding the political dynamics in each state. Evidence we present below indi-cates that the states that adopted legislation earliest were, in fact, those in which disabled workers were seemingly doing better than their disabled counterparts in states that adopted laws later. To the extent possible, we address this issue after we present our empirical results.

A second caveat is that our classication of states with respect to having disability discrimination legislation is crude, since it relies only on the presence of a law in the state at timetand does not control for nuances in the laws with respect to enforce-ment, stipulated penalties, size of employers covered, etc. Indeed, one could question whether it is accurate to uniformly classify state laws at all. We noted earlier that state laws vary widely with respect to several characteristics, but we cannot see a practical, parsimonious way to implement controls for all the differences using our estimation scheme and instead we simply estimate the average effects of these laws and the differences in outcomes across states with and without reasonable accommo-dation provisions in their laws.

There is also an issue of the timing of the laws. By using Census data, we effec-tively identify three time periods (1970, 1980, and 1990), but not the years in be-tween. We do not sort out the possible variation in responses to the law due to length

Beegle and Stock 843

of time since enactment but instead only estimate the average effect of laws passed earlier and later. One benet of using only three time periods, however, is that it substantially reduces concerns of serial correlation, which may bias the standard errors in difference-in-difference estimates (see Bertrand, Duo, and Mullainathan 2002).

Finally, assessing an individual’s disability status is clearly a key component of the analysis sincedisabilityis the variable that identies those protected by disability discrimination laws. Unlike studies evaluating legislation pertaining to race or sex, disability is multidimensional and difcult to measure (certainly more than sex and arguably more so than race). Moreover, our measure of disability is self-reported and thus subject to bias relative to a more objective measure (assuming, of course, that a perfectly objective measure could exist, since one could argue that even em-ployers or other outsiders may not objectively or consistently classify individuals as being disabled). In addition, more than one-third of state laws (and the ADA) cover ‘‘perceived handicaps.’’ In these cases, individuals who do not have a handicap may still be in the protected class if they are vulnerable to being perceived as having a handicap (for example, if an employee has a heart condition that is currently under control, but his employer reassigns him to less strenuous work out of fear that strenu-ous work will hasten a heart attack). Perhaps most importantly, as the rights of the disabled come increasingly to the forefront of policy discussions, individuals may actually change how they self-dene their disability status. That is, disability itself may be endogenous if individuals are more (or less) inclined to identify themselves as disabled in response to the disability discrimination legislation itself. For example, unemployed people might be disproportionately likely to self-report a work disability after disability discrimination legislation is passed in their state. On the other hand, the propensity to self-identify as disabled among employed people may be lower in states with laws if, for example, employees fear potential negative consequences of the laws. Acemoglu and Angrist (2001) describe this process as ‘‘composition bias.’’ In their analysis, however, Acemoglu and Angrist conclude that their results are not generated by such bias. Nonetheless, we address the issue to the limited extent possi-ble below, where we also nd no strong evidence of composition bias.

IV. Data Sources

ex-clude those with missing data (for example, those who reported being employed, but did not report their industry or earnings). For the earnings analysis, we limit the sample to full-time workers (those working 27 or more weeks per year and 30 or more hours per week), dening an individual as employed if we observe positive earnings and hours and weeks worked for the previous calendar year. Our earnings variable is the log of annual earnings, and we control for weeks and hours worked as regressors.11In addition, we exclude from the earnings regressions those whose real hourly wages would be less than $1.00 (in 1980 dollars), based on half-time half-year work. Finally, as mentioned above, the measure of disability in the Census that we use is drawn from self-reports of the presence of any disability that limits work.12

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics by each Census year for disabled and nondis-abled individuals. Approximately 10 percent of the population reports a disability limiting work, with slightly more reporting a disability in the 1970 Census than the 1990 Census (10.6 versus 9.4 percent). In comparison, DeLeire (2000) nds a similar proportion of individuals in the SIPP classied as disabled (covering the period 1986– 95), while Acemoglu and Angrist (2001), using individuals aged 21–58 in the 1988– 97 CPS, report a smaller fraction of the population as disabled.13

As expected, labor force participation and employment rates are low for the dis-abled, with an average of 34 percent of disabled individuals participating in the labor force during the 1970– 90 period, and 26 percent of disabled individuals employed. The labor force participation and employment rates for the nondisabled population are signicantly higher (73 and 65 percent, respectively). Similarly, a smaller fraction of disabled than nondisabled individuals were engaged in full-time employment. Among the employed, disabled workers worked fewer weeks and hours and had an average of 40 percent lower annual earnings than nondisabled workers.

Across-time comparisons reveal that the labor force participation rates of disabled workers declined from 39 to 33 percent over the 1970– 90 period, while employment rates for this group fell from 32 to 23 percent. At the same time, however, the

educa-11. We use annual earnings because wages are not reported in the Census. The Censusweeks of work variable refers to the weeks worked in the previous calendar year, whilehours of workrefers to usual weekly hours in the Census year. These variables are coded in the Census data as categorical variables; we use the midpoints of the categories.

12. In 1980 and 1990, the Census question stipulated that the disability had to have lasted at least six months. The 1970 Census did not include this stipulation, but did ask how long the disability had lasted. To make 1970 comparable with the other years, we do not classify persons as disabled unless their disability lasted at least six months (Ruggles and Sobek 1997). The Census also includes a more restrictive question about a disability thatpreventswork, which we do not use here.

B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

Table 3

Summary Statistics for Disabled and Nondisabled Individuals by Census Year

1970 1980 1990 All Years

Percent disabled 0.106 0.098 0.094 0.099

Da ND D ND D ND D ND

In labor force 0.392 0.659 0.309 0.726 0.328 0.781 0.341 0.728

Employed 0.319 0.597 0.223 0.643 0.234 0.700 0.256 0.652

Ln(earnings)b 8.29 8.47 8.88 9.12 9.34 9.66 8.81 9.17

Weeks employed 43.85 45.76 43.39 45.83 43.42 46.27 43.58 45.90

Hours worked 38.35 39.35 37.83 39.41 37.40 40.18 37.89 39.70

Full-time employment 0.248 0.498 0.162 0.525 0.164 0.573 0.190 0.535

Age 46.11 37.48 46.74 35.96 45.58 36.66 46.13 36.63

Female 0.513 0.557 0.512 0.539 0.491 0.531 0.505 0.541

White 0.848 0.891 0.807 0.849 0.800 0.823 0.817 0.852

Black 0.142 0.097 0.155 0.101 0.140 0.094 0.145 0.097

Less than high school 0.635 0.396 0.528 0.263 0.390 0.168 0.511 0.264

High school graduate 0.245 0.390 0.310 0.418 0.350 0.373 0.305 0.393

Some college 0.083 0.139 0.112 0.194 0.196 0.292 0.133 0.216

Four years of college 0.024 0.050 0.030 0.078 0.045 0.121 0.034 0.086

More than four years of college 0.012 0.026 0.019 0.046 0.019 0.046 0.017 0.040

SMSA 0.614 0.654 0.782 0.825 0.758 0.814 0.722 0.773

Observations 93,441 784,473 103,915 953,736 109,598 1,061,383 306,954 2,799,592

Note: The denition of disability is based on the U.S. Census and includes those reporting a disability limiting work.

tional attainment of the disabled improved substantially. The fraction of the disabled with less than a high school education fell from 64 percent in 1970 to 39 percent in 1990, while the fraction of the disabled with at least some college rose from 12 to 26 percent over the same period. Other demographic characteristics of the disabled do not appear to have changed much over the two decades.

Table 3 also allows us to compare labor market outcomes for disabled individuals relative to the nondisabled. For example, the gaps in labor force participation and employment rates between the disabled and nondisabled grew over the time period, from a labor force participation rate gap of 0.27 (that is, the nondisabled labor force participation rate was 0.27 higher than that of the disabled) and an employment rate gap of 0.28 in 1970, to gaps of 0.45 and 0.47, respectively, in 1990. The wage gap between disabled and nondisabled workers also grew over the period, from 0.18 log points in 1970 to 0.32 log points in 1990. Thus, the period 1970– 90 is one of an absolute decline in labor force participation and employment of the disabled, as well as relative declines in these outcomes (and relative earnings) as compared to the nondisabled. In the next section, we assess the impact of disability discrimination legislation on these outcomes.

V. Empirical Results

As a rst step toward examining the impact, if any, of state-level disability discrimination laws, in Table 4 we explore the differences in mean out-comes for disabled workers in states that passed a law by 1980 and those that had no law by 1980. This breakdown allows us to generate a simple comparison of the status of the disabled in states that passed laws relative to that of the disabled in states that did not pass laws (and both relative to the nondisabled), before and after the laws were passed.

For 1970, before any state-level disability laws were enacted, we see that disabled people in states that enacted legislation by 1980 had higher rates of labor force participation, employment, and earnings than the disabled in states that did not enact disability discrimination laws by 1980. For example, in 1970, the mean labor force participation rate for the disabled was 40 percent in states that enacted legislation by 1980 but was only 35 percent in states that did not enact legislation by 1980. The nondisabled, on the other hand, had roughly similar labor market participation rates across the two sets of states, with the additional implication that the labor market status of the disabled relative to the nondisabled was also better in the states that passed laws.

participa-B

ee

gle

and

Stoc

Table 4

Summary Statistics for Disabled and Nondisabled Individuals in States with and without Discrimination Laws by 1980

1970 1980 1990

States without States with States without States with States without States with Law by 1980 Law by 1980 Law by 1980 Law by 1980 Law by 1980 Law by 1980

Percent disabled 0.123 0.102 0.114 0.094 0.109 0.090

Da ND D ND D ND D ND D ND D ND

In labor force 0.350 0.646 0.404 0.663 0.284 0.720 0.317 0.727 0.291 0.773 0.340 0.783

Employed 0.291 0.584 0.327 0.601 0.208 0.642 0.227 0.644 0.209 0.691 0.241 0.702

Ln(earnings)b 8.07 8.30 8.35 8.50 8.80 9.04 8.90 9.14 9.24 9.55 9.37 9.69

Weeks employed 43.44 45.67 43.96 45.77 43.25 45.73 43.44 45.85 43.31 46.15 43.45 46.30 Hours employed 38.19 39.95 38.40 39.21 37.94 39.83 37.80 39.31 37.63 40.46 37.34 40.11 Full-time employment 0.221 0.489 0.255 0.500 0.150 0.528 0.166 0.524 0.147 0.570 0.170 0.574 Number of observations 20,786 147,521 72,655 636,952 24,258 188,672 79,657 765,064 25,473 208,260 84,125 853,123

a.D5disabled;ND5nondisabled.

b. The variablesln(earnings),weeks employed,andhours employedare conditional on employment. The number of observations for these variables is lower than that

tion rates, the slightly larger decline in labor force participation among the disabled in those same states led to a narrowing of the gap in participation rates by 1980. Disabled workers’ earnings, on the other hand, rose in both sets of states, but rose by more in the states that did not pass disability discrimination laws.

Note that because all but two states had laws by 1990, the comparison of outcomes between 1980 and 1990 is effectively a comparison among states that passed laws earlier (by 1980) relative to states that passed laws later (by 1990). From 1980 to 1990, the disabled in states with the more recently enacted laws (states without a law by 1980, but primarily with laws by 1990) had stagnant employment rates, while the disabled in states with older laws (states with laws by 1980) had slight increases in employment. Disabled workers’ earnings increases were similar across the sets of states, rising by 0.47 log points in the states with the earlier laws and by 0.44 log points in the states that passed laws after 1980. Thus, it appears that the states that passed laws earlier were those where the disabled were faring relatively better in terms of labor force participation and employment rates.

Finally, as shown in Table 4, there are also differences in labor market outcomes for the nondisabled over the same period, some of which change differently across the states with and without disability discrimination laws, implying differences in aggregate trends in the states with and without such laws. In our regression esti-mates below, we control for these trends and obtain the difference-in-difference-in-difference estimates by subtracting from the difference-in-difference-in-difference-in-difference-in-difference-in-differences described above for the disabled the same difference-in-differences for the nondisabled. Thus, we estimate an impact of a disability discrimination law only if an outcome changes differently for the disabled in states with laws relative to the disabled in states without laws, and only if this difference-in-differences changes differently for the disabled and the nondisabled.

Table 5 presents our estimates of the impact of the disability discrimination laws on labor force participation (Panel A) and employment (Panel B) using a linear probability model (probit and logit estimates yielded similar results). Column 1 in-cludes the variable for the presence of a disability law (DDL), while Columns 2– 5 include state by year interactions, which preclude inclusion of DDL. In Column 3 we includeyear dummy * disabled andstate dummy *disabled interactions to allow for differing state effects and time trends inYfor the disabled and nondisabled. In Column 4 we add additional controls for age and age trends. We also expand the specication to include an interaction between disabled and a dummy variable indicating supplemental SSI payments by state and year to address the prediction from theory that nonlabor income for the disabled that varies across states may bias our results, particularly if the nonlabor income moves systematically with state laws. In the nal column, Column 5, we add an interaction term for disabled persons whose state disability law includes a reasonable accommodation clause.

In all specications, disabled individuals had signicantly lower levels of labor force participation and employment than the nondisabled. The estimate on theDIS

variable is stable across specications and similar in size for the labor force participa-tion and employment models, indicating roughly 28 to 44 percentage point lower labor force participation and employment rates among the disabled than the nondis-abled.