Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:45

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Impact of Faculty-Student Interactions on

Teaching Behavior: An Investigation of Perceived

Student Encounter Orientation, Interactive

Confidence, and Interactive Practice

Robert Frankel & Scott R. Swanson

To cite this article: Robert Frankel & Scott R. Swanson (2002) The Impact of Faculty-Student

Interactions on Teaching Behavior: An Investigation of Perceived Student Encounter

Orientation, Interactive Confidence, and Interactive Practice, Journal of Education for Business, 78:2, 85-91, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599703

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599703

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 30

View related articles

The Impact of Facu Ity-St udent

Interactions on Teaching Behavior:

An Investigation of Perceived

Student Encounter Orientation,

Interactive Confidence, and

Interactive Practice

ROBERT FRANKEL

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

East

Carolina

UniversityGreenville, North Carolina

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

SCOlT

R. SWANSON

University of Wisconsin-Whitewater Whitewater, Wisconsin

s a service that we deliver, teaching

A

has been identified as one of the most intangible of products. “This intan- gibility has implications not only for ‘tra- ditional’ service businesses, but also for classroom education” (Straughan, 1998, p.1). One consequence of the intangible nature of teaching is the variability in perceptions of the interactions that occur with students. During faculty-student encounters, a variety of things transpire that can create satisfaction or dissatisfac- tion for either party. Several recent stud- ies of higher education have examined student satisfaction through consumerperspectives (Davis

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Swanson, 2001;Guolla, 1999; McCollough & Gremier, 1999; Stafford, 1994). Unfortunately, the faculty member’s perspective is rarely, if ever, formally considered. In fact, previous research has examined sat- isfactory and dissatisfactory professor- student interactions and their impacts only from the student’s perspective (Davis & Swanson, 2001; Swanson &

Davis, 2000). Yet it is important to under-

ABSTRACT. Previous research has examined satisfactory and unsatisfac- tory faculty-student interactions from only the student’s viewpoint. In this research, the authors used a national sample of marketing professors’ self- reported satisfactory and dissatisfac- tory critical incidents with students. Their findings support previous inci- dent classification schemes. They identified five specific behavior out- comes resulting from critical interac- tions with students: method and material changes; requirements clari- fication; reinforcing actions; student praise; and greater authoritativeness. The authors also introduce three con- structs-student encounter orienta- tion, instructor interaction confi- dence, and instructor interaction practice-and discuss the relation- ship of constructs to incident classifi- cations, the (dis)satisfactory nature of an interaction, and behavioral responses.

stand them from the educators’ perspec- tive as well. We believe that identifying commonly occurring incident types and related response behaviors would help professional educators assess their expe-

riences and improving their teaching performance.

In this study, we examined professors’ self-reported (dis)satisfying critical inter- actions with students and the impact that these encounters have had on their subse- quent teaching behaviors. We also exam- ined (a) the reported incidents through faculty members’ perceptions of the stu- dent’s behavior during the encounter and (b) the faculty members’ interaction adaptability (i.e., confidence in, and practice of, a variety of approaches based on the teaching situation).

Specifically, we were guided by the following questions:

Are the incident group classifica- tions of (dis)satisfactory professor-stu- dent encounters, as provided by profes- sors, consistent with those identified in student samples?

How do incident group classifica- tions and the (dis)satisfactory nature of interactions with students influence pro-

fessors’ future teaching behaviors?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

NovembedDecember 2002 85

Is the student’s encounter orienta- tion, as perceived by the Iprofessor, associated with particular incident group classifications, the (dis)satisfac- tory nature of an interaction, and/or a professor’s future behaviors?

Is a professor’s interaction adapt- ability associated with the (dis)satisfac- tory nature of an interaction and/or with the professor’s future behaviors?

At a basic level, student-professor interactions can be classified as satisfy- ing or dissatisfying. Satisfaction is a postconsumption evaluation. An indi- vidual relies on his or her expectations to make a judgment regarding the extent of generated fulfillment associ-

ated with level of satisfaction (Oliver

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& DeSarbo, 1988; Yi, 1990). These

expectations constitute standards that are compared with what the individual believes or perceives has happened during the interaction.

To better understand the faculty mem- ber’s perspective of professor-student (dis)satisfactory interactions and the impact of these experiences on teaching behaviors, in this study we used the crit- ical incident technique (Flanagan, 1954). A critical incident is “an observable human activity that is complete enough in itself to permit inferences to be made about the person performing the act” and that “contributes to or detracts from the general aim of the activity in a significant way” (Bitner, Booms, & Tetreault, 1990, p. 73). We examined these critical inci- dents with respect to (a) the encounter orientation of the student (as perceived by the professor) and (b) the professor’s interaction adaptability.

Student encounter orientation repre- sents the professor’s perceptions of a stu- dent’s behavior during a critical interac- tion that resulted in (dis)satisfaction. We adapted the construct from Williams and Spiro (1985) and introduced it into an educational context. Specifically, we defined student encounter orientation as the student’s level of preoccupation with self and his or her level of concern regarding the instructor during a profes- sor-student encounter. It measures a stu- dent’s friendliness and attentiveness toward the instructor together with the student’s self-concern.

We relied on previous sales literature

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

86

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education f o r Busine(Porter & Inks, 2000; Spiro & Weitz, 1990) for our definition of interaction adaptability (the idea that instructors may interact differentially with differ- ent students). Although the objectives of selling and teaching can be quite dif- ferent, the ability and willingness of a salesperson to “connect” with his or her intended target and modify his or her strategy based on observed reactions to solve a problem would appear to be similar to that ability in an instructor. Arguably, there are no universally effective teaching methods. Student learning takes place in a variety of situ- ations (both inside and outside the classroom) involving multiple profes- sor-student interactions. We suggest that professors become involved in a variety of teaching situations and encounter a wide range of students; each situation and student may require the adaptation of unique approaches based on the learning objective at hand or the knowledge level and personality of the student. Some professors may be more flexible in how they approach stu- dent encounters than others. Instructors demonstrate an adaptive interaction style when they have confidence in their abilities and use a variety of instructional approaches across various learning encounters. They make adjust- ments based on the feedback that they receive during these interactions. Those with a nonadaptive interaction style, on the other hand, use of the same proce- dure or approach for all encounters with students.

Method

Data Collection

Using a commercially purchased list- ing, we randomly selected 1,508 market- ing professors in the United States for a questionnaire mailing. We sent a follow- up reminder card 1 week after the initial mailing. A total of 47 envelopes were returned as undeliverable. Out of 267 surveys (18.3%) returned by the respon- dents, 221 were complete and used in

= 86).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Seventy-six percent (168) of the respondents were men, and the respon-dents reported a college teaching expe- rience of 2 to 45 years (m = 18.9 years).

Our (nsatisfactory = 35; ‘dissatisfactory

ss

Data Analysis

As the starting point for the content analysis of the critical incidents collect- ed in this study, we relied on previous research on (dis)satisfactory service encounters (Bitner, Booms, & Mohr, 1994; Bitner et al., 1990; Gremler &

Bitner, 1992; Kelley, Hoffman, &

Davis, 1993) as well as instructor-stu- dent interactions based on student sam- ples (Davis & Swanson, 2001; Swanson

& Davis, 2000). We asked professors to (a) think of a recent particularly satisfy- ing or dissatisfying interaction with a student and (b) describe the particular situation in detail. Next, we asked each respondent to discuss in an open-ended question whether and how the student interaction influenced the respondent’s subsequent behaviors or actions.

After careful repeated readings, the second author sorted similar (dis)satis- factory incidents and the reported subse- quent behaviors into three and five cate- gories, respectively. The first author then independently sorted the 22 1 incident forms into one of the three incident clas- sification groups and five behavioral outcome categories to assess the inter- rater reliability (Ir) of the category assignments (Perreault & Leigh, 1989). Interrater reliability (Ir) for agreement among the three incident groups and five behavioral outcome groups was 3 9 and .9 1, respectively. We placed responses for which there was disagreement in a mutually agreed-upon category.

In the next section of the question- naire, we adapted previously developed scales to measure (a) the perceived stu- dent encounter orientation and (b) the professor’s interaction adaptability. We measured student encounter orienta- tion, as perceived by marketing profes- sors in the reported critical incidents, through six modified items from Willams and Spiro (1985). Higher scores on the scale suggest that the pro- fessor perceived that the student whom he or she interacted with was person- able and attended to what the professor said, whereas lower scores imply that the student was not easy to talk to or interested in what the professor had to say. We measured interaction adaptabil- ity through seven modified items from Spiro and Weitz (1990).

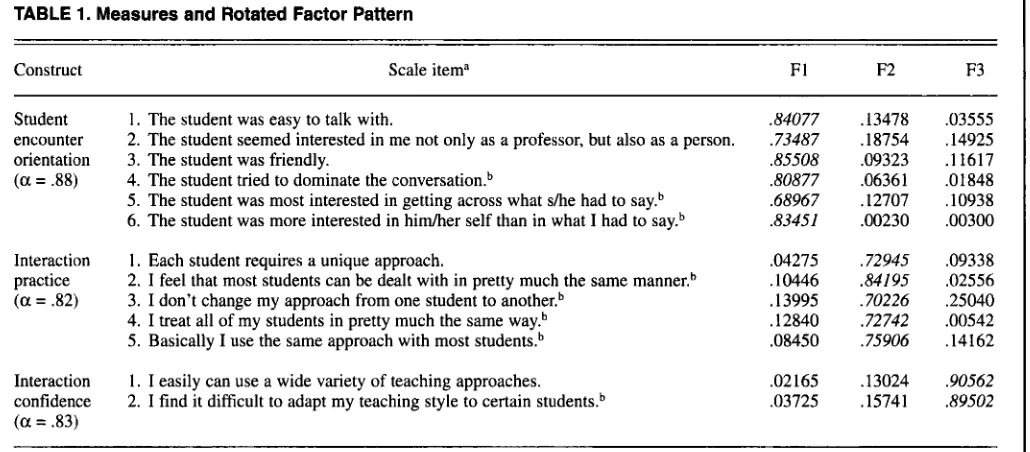

We conducted exploratory factor analysis to determine the factor struc- ture of the scales that we used. Princi- pal components analysis with varimax rotation revealed a three-factor struc- ture. All factors had eigenvalues of 1.0 or greater, surpassed a minimum factor loading of .40, demonstrated strong levels of reliability (alphas of 0.82-0.88), and exhibited no substan- tially significant crossloadings. Taken together, the three factors accounted for 66.0% of the total variance. These results support previous research

(Marks, Vorhies,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Badorick, 1996) intheir suggestion that adaptive behaviors may be two-dimensional. We provide the factor loadings and corresponding

questions in Table 1.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Findings

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Critical Incident Groups

Three general group classifications emerged from our analysis of the pro- vided incidents. These group classifica- tions are similar to those found in both the general services literature (Bitner et al., 1994; Bitner er al., 1990) and previ- ous professor-student interaction research (Davis & Swanson, 2001; Swanson & Davis, 2000). Thus, they provide support to the generalizability

of the classification scheme found in those previous studies.

Critical Incident Group 1: Service sys- tem failure. This category, representing professor response to service delivery system failures ( n = 20), comprises inci- dents directly related to failures in the core services offered. These included incidents in which the services normal- ly available were absent or delayed. Failing to acknowledge a problem or ignoring student requests for help in understanding materials were associat- ed with reported dissatisfactory experi- ences. Satisfactory encounters were reported when things were well explained and detailed feedback was provided for the creation of a complete understanding of the issues involved.

Critical Incident Group 2: Response

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

to student needs and requests. In thisgroup of incidents ( n = 107), students were viewed as responsible for creating the initial situation. Specifically, student errors and preferences (e.g., the familiar refrain “I have a problem”) fell into this category. Responses to student prefer- ences included incidents in which the student made requests to m i s s a class or change a test or presentation date, paper due date, or grade. Admitted student error occurred if the triggering event

involved student acknowledgment of his or her own mistake (e.g., not following directions when performing work, miss- ing scheduled exams and classes, or los- ing assignments).

Critical Incident Group 3: Unprompted professor actions. This final category consisted of incidents ( n = 84) that were directly attributable to the professor’s actions, which often exceeded students’ current expectations or adjusted stu- dents’ future expectations. Incidents in this group were related to particularly extraordinary professor actions or expressions, attention paid to the stu- dent, and professor behaviors related to norms such as honesty and fairness.

Behavioral Responses to Critical Incidents

After describing a (dis)satisfactory incident, respondents stated whether the interaction influenced their subsequent behaviors or actions. Several respon- dents (n = 18) provided indefinite state- ments such as “it is too early to know how it will influence my future actions,” “the interaction was too recent to respond to this question,” or “time will

tell.” The majority of the subjects ( n =

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

203), however, reported a behavioral

response to the provided critical inci-

TABLE 1. Measures and Rotated Factor Pattern

Construct Scale itema F1 F2 Student 1 . The student was easy to talk with. .84077 .13478 encounter .I8754 orientation 3. The student was friendly. .85508 .09323

( a = 38) 4. The student tried to dominate the conversation.b .80877 .06361

.68967 .I2707

33451 .00230 2. The student seemed interested in me not only as a professor, but also as a person. ,73487

5. The student was most interested in getting across what s h e had to say.b 6. The student was more interested in himher self than in what I had to say.b

Interaction 1. Each student requires a unique approach. .04275 .72945

practice ,10446 .84195

( a = .82) .13995 .70226

.I2840 .72742

.08450 .75906

2. I feel that most students can be dealt with in pretty much the same manner.b 3. I don’t change my approach from one student to another.b

4. I treat all of my students in pretty much the same way:

5. Basically I use the same approach with most students.b Interaction

confidence

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(a = 3 3)

1. I easily can use a wide variety of teaching approaches. 2. I find it difficult to adapt my teaching style to certain studenkb

,02165 .13024 ,03725 .I5741

F3 .03555 .14925

.I 1617 .O 1848

,10938

.00300

.09338 .02556 .25040 .00542 .I4162

.90562 .89502

Note. Italic figures represent items that loaded on the respective factor.

“All questions were answered on a 7-point response scale ranging between 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).bThese items were reverse scored.

NovembedDecember 2002 87

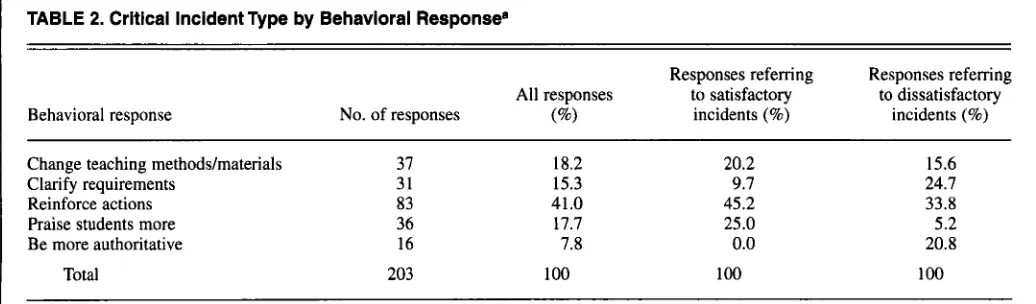

[image:4.612.53.568.484.710.2]dent. Five specific categories emerged from the analysis; we summarize these

findings in Table 2.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Behavior Change 1: Change in teaching methods or materials. Responses classi-

fied into this group (n

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= 37, 18.2%).focused on the instructor’s incorpora-

tion of new material into classes (e.g.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

“Ihave tried to be more creative in terms of problems, cases, and projects within the course structure”), making adjust- ments in response to student requests (e.g., “I now both formally and infor- mally survey my students to determine how effective my techniques have been. Then I modify my approach to

reachhnfluence others in the future”), and providing additional attention to

identified problem areas (e.g., “I now

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

try to integrate a review of key concepts before tests”). All the cases in this cate- gory focused on changing either the method of presentation of the class materials (e.g., “I will take unpopular

stands in order to encourage and foster student debate and increase student- teacher interactions in class”) or actual- ly changing the class materials (e.g., “focus on more challenging papers and assignments”).

Behavior Change 2: Clar$cation of requirements. A number of professors

(n = 31, 15.3%) suggested that the reported critical incident had influ- enced them to do a better job in clarify- ing their course requirements or assign- ment instructions. Responses in this category involved the professors’ focus- ing “on developing more objective

standards, clearer standards” that “communicate to students that certain things are expected-whether written or not.” Other representative responses included “be more detailed in my com- ments” and “explain to the entire class the nature of my expectations in the course.” In addition to class discussion, clarifying syllabi was also widely emphasized (e.g., “reworded syllabus to emphasize adherence to course requirements”; “included in my syl- labus a clear statement of policy regard- ing how the corrections to exam scores shall be handled”).

Behavior Change 3: Reinforcement of actions. Most responses in this catego- ry (n = 83, 41%) related to the inci- dent’s having motivated the respondent to continue or strengthen his or her resolve or reinforce the approach used during the student encounter. Some rep- resentative responses to satisfactory incidents were “I will continue to try to notice behaviors that indicate problems and will try to help where I can” and “it reinforced my conviction that students who are advised and encouraged thoughtfully and caringly, with atten- tion to both their intellectual and their emotional situation, virtually always respond positively.” Many of the behav- iors associated with reported dissatis- factory incidents also reinforced, or failed to result in changes to, respon- dents’ actions (e.g., “I don’t know how

to deal with these situations in a man- ner which will please a student. I try to get them to see things from my per- spective, which is difficult”).

Behavior Change 4: Praising students more. This category involved responses related to additional efforts to encour- age, strengthen, and praise students (n =

36, 17.7%). Instructors noted that they now “focus on the positive instead of the negative” and “have tried to be even more courteous and helpful” as a result of the reported critical incident. This emphasis on complimenting students more was tempered by some respon- dents’ preference for using additional praise under only certain conditions related to class work (e.g., “I have tend- ed to increase my use of praise of good work as opposed to negative comments about less good work” and in-class behaviors (e.g., “I try to make sure I praise those who come to class and are prepared for discussion”).

Behavior Change 5: Increase in author- itativeness. These responses ( n = 36, 17.7%) were all associated with dissat- isfactory incidents (20.8%). In all of these cases, the professors noted that they were taking a more authoritative and less friendly stance in confronta- tions with students. This stance appeared to be brought on by breaches of trust (e.g., “I am not as trusting

regarding these students”) or professor expectations not being met (e.g., “it is embarrassing to coddle them”). As a result, respondents became less flexible (e.g., “I have become more hard-

nosed”) and began setting policies “with no exceptions.”

Through a chi-square analysis, we found that professor behavioral

[image:5.612.46.564.564.716.2]response was related to the (dis)satisfac-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 2. Critical incident Type by Behavioral Responsea Behavioral response

Responses referring Responses referring

All responses to satisfactory to dissatisfactory

No. of responses (%) incidents (%) incidents (%)

Change teaching methoddmaterials 31 Clarify requirements 31

Reinforce actions 83

Praise students more 36

Be more authoritative 16

Total 203

18.2 15.3 41.0 17.7 7.8

100

20.2 9.7 45.2 25.0 0.0

100

15.6 24.7 33.8 5.2 20.8

100

~~~~~ ~

2*(4, N = 203), = 45.44; p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

< ,00100 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businesstory nature of critical student-professor

interactions

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(p < .001). Satisfactoryincidents overwhelmingly generated one of three reactions: (a) reinforcement of respondent behaviors, (b) engaging in additional efforts to praise students, or (c) changing teaching methods or materials to create similar experiences in the future. Dissatisfactory incidents generated a somewhat broader, more balanced set of reactions: (a) reinforce- ment of professor behaviors, (b) work- ing to clarify course requirements or assignment instructions, and (c) becom- ing more authoritative or changing teaching methods or materials to avoid similar experiences in the future.

It is interesting to consider the five

response behaviors with regard to the three incident group classifications. Dif- ferences in reported teaching behavior changes emerged across critical incident

types (see Table

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3). Reinforcement ofthe professors' actions was the most prominent response in each critical inci- dent group type. No other response behavior exhibited the same consistency

across critical incident group type.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The Role

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of (Perceived) Student Encounter OrientationTo explore further professor-student interactions and postincident professor behaviors, we used perceived student encounter orientation. As shown in

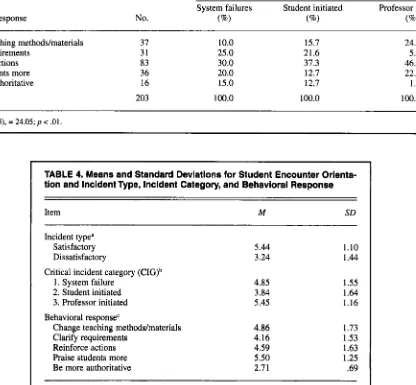

Table 4, analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated a statistically significant rela- tionship (p < .001) between perceived student encounter orientation and (a) whether the incident reported was satis- factory or dissatisfactory, (b) the critical incident classification, and (c) reported behaviors.

First, not surprisingly, compared with the responses of professors report- ing dissatisfactory encounters, the responses of professors discussing sat- isfying incidents referred to students' being easier to talk with, friendlier, and more interested in the professors' view- point. Duncan's posthoc test findings suggested that orientation scores were

[image:6.612.104.520.325.710.2]significantly lower in incidents attrib-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 3. Critical Incident Categories (CIG) by Behavloral Responsea 5 P e of

behavioral response

System failures Student initiated Professor initiated

No. (%)

(%I

(%I

Change teaching methods/materials 37 10.0 15.7 24.1

Clarify requirements 31 25.0 21.6 5.1

Reinforce actions 83 30.0 37.3 46.8

Praise students more 36 20.0 12.7 22.8

Be more authoritative 16 15.0 12.7 1.3

Total 203 100.0 100.0 100.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

%*(8, N = 203), = 24.05; p < .01.

TABLE 4. Means and Standard Deviations for Student Encounter Orienta- tion and Incident Type, Incident Category, and Behavioral Response

Item M SD

Incident type" Satisfactory Dissatisfactory

1 . System failure

2. Student initiated

3. Professor initiated Behavioral responseC

Change teaching methoddmaterials Clarify requirements

Reinforce actions Praise students more Be more authoritative

Critical incident category (CIG)b

5.44 3.24 4.85 3.84 5.45

4.86 4.16

4.59 5.50 2.7 1

1.10 I .44 1.55

1.64

1.16 1.73 1.53 1.63 1.25 -69

T ( I , 207) = 154.98, p < .001. bF(l, 206) = 28.45, p c ,001. 'F(4, 195) = 10.58.p c .001.

NovembedDecember 2002 89

[image:6.612.133.477.490.710.2]TABLE 5. Means and Standard Deviations for Professor Interaction Prac-

tice and Incident Type and Behavioral Response

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Item

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M SDIncident typea Satisfactory Dissatisfactory Behavioral responseb

Change teaching methoddmaterials Clarify requirements

Reinforce actions Praise students more

Be more authoritative

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4.88 4.3 1

4.35 4.40 4.81 5.12 4.27

1.19

1.27

1.16 1.16 1.37

I .02

1.27

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

aF(l, 208) = 10.77, p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

< .01. bF(4, 197) = 2.85, p < .05.zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

uted to student actions. In addition, rel- ative to all other behavior categories, the category involving students’ being perceived as having tried to dominate a critical classroom interaction elicited the most professor responses involving a desire to increase authoritativeness in the future. Higher perceived student encounter orientation scores were asso- ciated with praising behaviors, rein- forcement, and the clarifying of requirements.

The Role of Interaction Con3dence and Interaction Practice

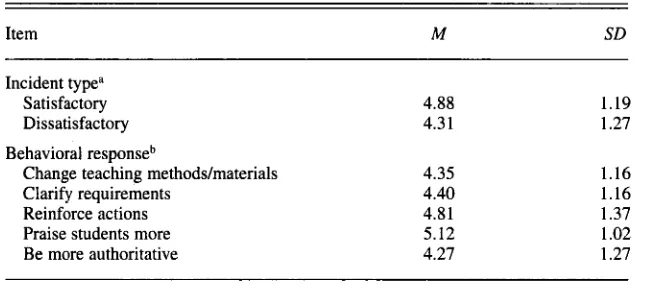

We next sought to explore the poten- tial relationship of the professors’ inter- action confidence and interaction prac- tice to the (dis)satisfactory nature of the critical incidents and the reported behaviors. We display these results in Table 5. Self-reported confidence in using a variety of different teaching approaches was not significantly related

(p > .05) to the (dis)satisfactory nature

of the reported incident or to subsequent reported behaviors. However, interac- tive practice was significantly related to the satisfactory or dissatisfactory nature of a reported incident (p

c

.Ol), as well as to postincident behaviors (p < .05).Duncan’s posthoc test results indicated that professors who had a higher level of interaction practice were significantly more likely to engage in encouragement and praising of students than in clarifi- cation of requirements, changing teach- ing materials or methods, or being more authoritative.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered new information pertaining to critical pro- fessor-student encounters by examining professors’ perspectives of these inci- dents rather than the student viewpoint, as previous researchers have done. Despite its exploratory nature, this research adds to the business education literature in several notable ways.

First, similarly to previous critical incident research in the services (Bitner et al., 1994; Bitner et al., 1990) and edu- cation (Swanson & Davis, 2000), this study indicates three incident group- ings: service system-based, student- based, and professor-based groupings. Thus, our results are consistent with the findings of a limited but growing body of work aimed at developing a rigorous taxonomy of critical incidents. Our results suggest that education is in fact similar to services in its delivery and evaluation processes.

Research comparing professor-stu- dent interactions based on a student per- spective rather than the professor’s viewpoint appear to have an attribution bias (Heider, 1958; Weiner, 1980, 1985). In this study, professors report- ing a student-provoked incident over- whelmingly indicated that the interac- tion was dissatisfying (82.9%), and

critical incidents based on system deliv- ery failures (1 1 .O%) or unprompted and unsolicited professor actions (6.1 %)

were dramatically less likely to be reported as dissatisfying. Swanson and Davis (2000) noted that a student sam-

ple reported dissatisfactory events most frequently when professors’ responses were unprompted and unsolicited (55.1%). They found that, from the stu- dents’ perspective, system delivery fail- ure (26.5%) and student-provoked inci-

dents (1 8.4%) were less likely to create dissatisfying encounters. Professors willing to consider this difference in perspective (or perhaps even query their own students) may discover avenues for self-improvement in their teaching style and process.

Discovering where a professor-stu- dent “disconnect” exists provides a potential opportunity for teaching improvement. Finally, these findings imply that the faculty member’s per- spective must be considered in an administration’s attempt to measure stu- dent satisfaction. Education is an inter- active process; an attribution bias sug- gests that only one party’s perspective is being measured and that the results may be distorted.

An additional insight concerns our finding that professors’ responses to these critical incidents do influence a broad spectrum of future teaching-relat- ed behaviors. It is interesting to note that, despite frequent commentary sug- gesting that professors are unwilling to experiment or alter their classroom approach because they have little moti- vation to do so, respondents in our study indicated that they were making changes in response to both satisfactory and dissatisfactory encounters with stu- dents. In other words, professors are indeed interested and willing to change and experiment.

We also found that student encounter orientation plays an influential role in faculty perceptions. Specifically, the more a student is perceived to be preoc- cupied with him- or herself, the more likely that the incident will be recalled as dissatisfying and the more likely that the instructor will become more authorita- tive in similar future situations. Con-

versely, when a student is perceived as entering

an

encounter with interest in the instructor’s viewpoint, the encounter is more likely to be recalled satisfactorily and to result in greater student praise and better clarification of course require- ments and assignment instructions in the future. It should come as no surprise that90 Journal of Education for Business

[image:7.612.58.384.77.222.2]most professors would find themselves more receptive to students who show interest and concern for their teacher’s role in their learning. Conversely, instructors should be conscious of not overreacting to a dissatisfactory incident in such a way that it punishes future stu- dents with overly authoritative actions.

Finally, we suggest that professors should encounter a variety of learning situations that require (a) confidence in using different approaches when neces- sary and (b) the practice of those differ- ent approaches. Confidence in using a

variety of interaction methods was

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

notsignificantly related to the (dis)satisfac- tory nature of the reported incidents or to subsequent faculty behaviors. This result is very interesting and contrary to our expectations. We interpret this lack

of statistical significance as

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an indica-tion that such a characteristic is a belief or self-confidence that a professor inherently develops and possesses. In most cases, this development is an important component of the “training” experience for (new) professors during a doctoral program. On the other hand,

interaction practice

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

wus significantlyrelated to what a professor reported as a defining critical student encounter and subsequent faculty behaviors. Profes- sors who used a variety of interaction approaches were more likely to recall satisfying encounters with students. In addition, these instructors were signifi- cantly more likely to make additional efforts to encourage, strengthen, and praise students to support appropriate behaviors. The implication is that prac- ticing adaptability creates a “win-win” or positive feedback atmosphere more effectively than does clarification, changes in materials, or increased levels

of authority.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Future Research Directions

Findings of this study suggest several important and interesting future research avenues. First, replication of this study is necessary to validate the differences in satisfactory versus dissat- isfactory professor perceptions. Such

studies hold promise for excellent appli- cation of attribution theory. Second, teaching has traditionally occurred in an environment where students directly interact with each other and their pro- fessors. The growth of Internet-based course delivery raises questions in regard to the types of interactions that may lead to satisfactory or dissatisfacto- ry experiences when there is naphysical classroom. Similarities and differences in critical incidents for environments where it is difficult to duplicate the face- to-face experience need investigation. Third, replicating this study in a global environment ( e g , several different countries and cultures) would be intriguing. Education is an important

component of the global economy.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Asmore professors become involved in teaching outside of their home country and classroom setting, understanding the similarities and differences (of pro- fessors) will likely be an important resource for those entering a culturally “different” classroom.

Finally, we can assume that greater experience developed over time will improve professors’ interaction skills and enable them to recognize a wider variety of incident situations and thus facilitate a greater range of responses when interacting with students. Never- theless, in this study we found that years of experience was not significantly related to either greater interaction con- fidence or practice in this study. Other researchers may wish to consider other variables antecedent to these constructs to provide a more complete understand- ing of what leads to both confidence in and actual practice of greater adaptabil- ity in teaching encounters. Exploring these research avenues should con- tribute to a better understanding of pro- fessor-student encounters.

REFERENCES

Bitner, M., Booms, B.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Mohr, L. (1994). Criti-cal service encounters: The employee’s view- point. Journal of Marketing, 58(October), Bitner, M., Booms, B., & Tetreault, M. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. Journal of Market- 95-106.

ing, 54(January), 71-84.

Davis, J., & Swanson, S. (2001). Navigating satis- faction and dissatisfactory classroom incidents.

Journal of Education f o r Business, 76(5), Flanagan, J. (1954). The critical incident technique.

Psychological Bulletin, Sl(July), 327-358. Guolla, M. (1999). Assessing the teaching quality

to student satisfaction relationship: Applied customer satisfaction research in the classroom.

Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice,

7(Summer), 87-97.

Gremler, D., & Bitner, M. (1992). Classifying ser- vice encounter satisfaction across industries. In C. Allen et al. (Eds.), Marketing theory and

application (pp. 11 1-1 18). Chicago, IL: Amer- ican Marketing Association.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interperson-

al relations. New York, N Y John Wiley and Sons.

Kelley, S., Hoffman, D., & Davis, M. (1993). A typology of retail failures and recoveries. Jour-

nal of Retailing, 69(Winter), 429-452. Marks, R., Vorhies, D., & Badovick, G. (1996). A

psychometric evaluation of the ADAPTS scale: A critique and recommendations. Journal of

Personal Selling & Sales Management, 16 (Fall), 5 3 4 5 .

McCollough, M., & Gremler, D. (1999). Guaran- teeing student satisfaction: An exercise in treat- ing students as customers. Journal ofMarketing

Education, 2I(August), 11 8-130.

Oliver, R., & DeSarbo, W. (1988). Response determinants in satisfaction judgments. Journal

of Consumer Research, 14(March), 495-507. Perreault, W., & Leigh, L. (1989). Reliability of

nominal data based on qualitative judgments.

Journal of Marketing Research, 26(May). 135- 148.

Porter, S., & Inks, L. (2000). Cognitive complexi- ty and salesperson adaptability: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Personal Selling &

Sales Management, l(Winter), 15-21. Spiro, R., & Weitz, B. (1990). Adaptive selling:

Conceptualization, measurement, and nomo- logical validity. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(February), 61-69.

Straughan, R. (1998). Delivering a satisfactory educational experience: The other half of the picture. Marketing Educator; 17(Spring), 1.5. Stafford, T. F. (1994). Consumption value and the

choice of marketing electives: Treating students like customers. Journal of Marketing Educa-

lion, 16(Summer), 26-33.

Swanson, S., & Davis, J. (2000). A view from the aisle: Classroom successes, failures, and recov- ery strategies. Marketing Education Review, lO(Summer), 17-25.

Weiner, B. (1980). Human motivation. New York, N Y Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psycho-

logical Review, 92(0ctober), 548-573. Williams, K., & Spiro, R. (1985). Communication

style in the salesperson-customer dyad. Journal

of Marketing Research, 12(November), 434-442.

Yi, Y. (1990). A critical review of customer satis- faction. In V. Zeithaml (Ed.), Review of market-

ing (pp. 68-123). Chicago, L: American Mar- keting Association.

245-250.

NovembedDecember 2002 91