Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 21:40

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Institutional determinants of Indonesia's sugar

trade policy

Tim Stapleton

To cite this article: Tim Stapleton (2006) Institutional determinants of Indonesia's sugar trade policy, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 42:1, 95-103, DOI: 10.1080/00074910600632401

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910600632401

Published online: 18 Jan 2007.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 125

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/06/010095-9 © 2006 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074910600632401

* The author thanks Andrew MacIntyre and the Asia Pacifi c School of Economics and

Government, ANU, where he undertook this project as a visiting scholar; Peter Drysdale for his encouragement and guidance throughout; three anonymous referees for valuable feedback on earlier drafts; and a number of people in Indonesia for their time and advice.

INSTITUTIONAL DETERMINANTS OF

INDONESIA’S SUGAR TRADE POLICY

Tim Stapleton*

Australian National University

An analysis of contemporary sugar trade policy in Indonesia highlights problems in the institutional framework for trade policy making. The institutions through which sugar trade policy is formulated entrench the interests of rent-seeking bureaucrats, import licence holders and traders to the detriment of consumers and downstream producers of processed products. Moreover, the resulting trade policy regime has problematic effects on sugarcane farmers. The structure of regulatory interven-tion is due less to democratic pressures than to the inclusion of vested interests in the institutions that formulate policy. Further, the lack of effective mechanisms for inter-ministerial coordination and for resolving confl icting policy preferences

among ministries hinders the development of coherent trade policy and obstructs reform efforts. An institutional framework that facilitates representation of all ests affected by sugar trade policies and public scrutiny of the effects of policy inter-vention is likely to deliver better outcomes for consumers and producers alike.

INTRODUCTION

The institutional framework for trade policy making is a critical element in the political economy of regulation in the sugar sector in contemporary Indonesia. Sugar, like other traded agricultural products, has a long history of protection. In 1998 the highly regulated and protectionist sugar trade regime that prevailed under Soeharto’s New Order government was liberalised to meet the loan condi-tions of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Yet despite subsequent demo-cratic reforms, the sugar sector has been heavily re-regulated since 2002. Seasonal import quotas, import licensing arrangements, inter-island trade restrictions, specifi c tariffs, and a high minimum price for domestic sugarcane procurement

have been instituted. Consequently, consumers and downstream industries are once again burdened with domestic prices approximately twice the international level, just as they were during the Soeharto era when the national logistics agency, Bulog, was afforded a virtual monopoly over imports, domestic procurement and marketing (Iqbal et al. 1999: 1, 8).

BIESApr06.indb 95

BIESApr06.indb 95 27/2/06 5:18:06 PM27/2/06 5:18:06 PM

96 Tim Stapleton

As the IMF’s infl uence over trade policy diminished in the post-crisis period,

overlapping, contradictory and protectionist sugar trade policies began to emerge. This new policy regime is of limited benefi t to smallholder cane farmers,

particu-larly on Java, where nearly 50 outdated, predominantly state-owned mills pro-duce approximately 60% of domestic sugar (Stapleton 2005: 28). As argued in detail below, the regulatory regime discourages procurement of sugarcane culti-vated domestically, fails to address declining sucrose extraction rates, and deters diversifi cation into more profi table agricultural activities. At the same time, two

relatively new, lower cost, private sector plantations are able to derive excess profi ts in Sumatra’s Lampung province (Abidin and Ismono 2004), which now

accounts for up to 40% of sugar production (Stapleton 2005: 28).1

Thus intensifi ed lobbying from producer interests—in particular, smallholder

cane farmers—in the post-crisis transition to democracy cannot adequately explain current regulatory distortions in the sugar sector. Although sectional interests may have a more powerful bearing on trade policy during democratic transitions (Liu 2002, cited in Basri and Hill 2004: 639), and can unduly infl

u-ence economic policy outcomes (Boediono 2005: 316), factors other than pressure from cane growers appear to have underpinned the re-regulation of Indonesia’s sugar industry—despite the fact that intervention is typically undertaken in their name. This paper argues that the nature of intervention in the sugar sector, and the ‘creeping protectionism’ evident in Indonesia generally (Basri and Soesastro 2005: 10–12; World Bank 2005: 4), are largely attributable to defi ciencies in the

institutional framework for trade policy making.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN SUGAR TRADE POLICY

On 1 January 2000, a 20% tariff on sugarcane and industrial-grade refi ned sugar

and a 25% tariff on white plantation sugar for human consumption (hereafter ‘white sugar’) were imposed (Finance Ministry decree 568/KMK.01/1999) and the minimum price paid on domestic sugarcane was set at Rp 2,600/kg of white sugar equivalent extracted by the mills (Forestry and Plantations Ministry decree 145/KPTS-VII/2000). Following President Megawati’s July 2001 election victory, low import prices and widespread smuggling2 to evade the tariff were damag-ing farm-gate returns, and threatendamag-ing the agriculture ministry’s legitimacy with farmers (JP, 1/5/2002). Agriculture minister Bungaran Saragih pushed for the imposition of higher tariffs on sugar, rice, soybeans and corn (JP, 26/6/2002)— notwithstanding the likelihood that this would boost smuggling and therefore do little to protect farmers. His proposal was successfully opposed by fi nance

minister Boediono, however. The Ministry of Finance (MoF) is responsible for tariff implementation, although other ministries are generally consulted and their advice sought through a Tariff Committee (Tim Tarif). This committee comprises trade experts and representatives from the agriculture, trade and industry minis-tries, but is responsible to the fi nance minister.

1 A small quantity of sugar is also produced in Sulawesi and Kalimantan, and in other provinces of Sumatra.

2 Including physical smuggling and administrative smuggling by collusion with cus-toms offi cials to avoid import duties.

BIESApr06.indb 96

BIESApr06.indb 96 27/2/06 5:18:06 PM27/2/06 5:18:06 PM

Although the traditionally protectionist Ministry of Trade (Basri and Hill 2004: 638) cannot impose tariffs, it has authority over various non-tariff barri-ers (NTBs). Previously, as the Ministry of Industry and Trade (MIT),3 it publicly advocated either an import quota system or a fl oor/ceiling price mechanism (JP,

4/5/2002)—its then minister, Rini Soewandi, asserting that consumers would be burdened with higher prices if tariffs were increased (JP, 26/4/2002), though in fact quotas or fl oor prices would have the same effect.

On 3 July 2002 (MoF decree 324/KMK.01/2002), Boediono sought to curb ram-pant under-invoicing by replacing the prevailing ad valorem tariffs with specifi c

tariffs of Rp 550/kg on sugarcane and Rp 700/kg on industrial-grade and white sugar (based on the logic that the quantity is easier to validate than the purchase price). These specifi c tariffs were equivalent to 30% and 35% ad valorem import

duties, according to the World Trade Organization (WTO 2003: 5–6), or an average of about 45% according to the World Bank (2005: 4). The Association of Indonesian Sugarcane Farmers (APTRI) played a signifi cant role in pushing for the new sugar

tariffs in 2002.4 Its supporters applied pressure by staging disruptive rallies and ransacking warehouses suspected of containing illegal imports (JP, 26/4/2002, 4/7/2002). Arum Sabil, head of APTRI in the operating region of one of the larg-est state-owned sugar plantations, lobbied key decision makers involved in the policy process (personal communication, 9/9/2005); again, such tactics ignored the reality that smuggling is encouraged rather than curbed by tariffs.

Boediono had engaged Soewandi in negotiations to formulate the tariff decree. However, immediately after it was issued the MIT erected an elaborate licensing system that limited the importation of industrial-grade sugar (10 August 2002) and of white sugar (23 September 2002) (MIT decrees 456/MPP/Kep/6/2002 and 643/MPP/Kep/9/2002). The new arrangements reallocated white sugar imports from 800 private importers (JP, 26/5/2003) to just fi ve entities: three of the

larg-est state-owned sugar plantation and mill management units, PTPN IX, PTPN X, PTPN XI5—which account for over 90% of white sugar produced on Java and over 60% in total (Stapleton 2005: 19)—and two state-owned trading fi rms, PT

Rajawali Nusantara Indonesia and PT Perdagangan Indonesia.6 The more market-oriented MoF lacked the authority or mandate to prevent MIT from instituting these arrangements, which effectively circumvented the tariff decree negotiated between the two ministers.

According to Marks (2004: 169),

… the Business Competition Supervisory Commission (Komisi Pengawas Per-saingan Usaha) … observed that the sugar import restraint system could give rise to cartel practices, and suggested that it be revised (Tempo Interaktif, 29/3/04). Nev-ertheless, the value of sugar imports increased by 54.2% between 2002 and 2003, even though the decree was issued in late September 2002. The cartel seems to have worked most imperfectly!

3 The trade and industry portfolios were formally separated in the October 2004 cabinet. 4 Interview with a senior member of the Megawati administration, 28/7/2005.

5 ‘PTPN’ stands for Perusahaan Terbatas Perkebunan Negara (state plantation company). 6 These fi ve designated importers lack suffi cient fi nancial and warehousing capacity, and

so engage traders to operate on their behalf.

BIESApr06.indb 97

BIESApr06.indb 97 27/2/06 5:18:07 PM27/2/06 5:18:07 PM

98 Tim Stapleton

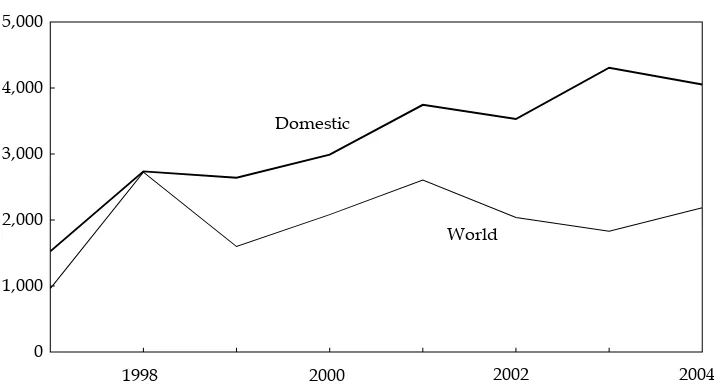

Marks goes on to detail new decrees issued early in 2004, which seemed likely to make the cartel more effective. By April 2003 the domestic retail price of sugar had surged to Rp 5,000–6,000/kg in some areas (JP, 22/4/2003, 1/5/2003), which, as fi gure 1 shows, was not attributable to any increase in the international price.

The price increases may refl ect the fact that with so few licensed importers there

is indeed a strong possibility of earning high profi ts through oligopolistic

behav-iour. MacIntyre and Resosudarmo (2003: 151–2) suggest that the price surge may have stemmed from a dispute between the licensees and the Directorate General for Customs and Excise over the division of these profi ts, which precipitated a

supply shortage by trapping a signifi cant quantity of white sugar in the ports.

Domestic prices have remained around twice the international level, despite Indonesia’s proximity to highly effi cient exporters such as Thailand and

Aus-tralia. High prices are a signifi cant burden for consumers and erode the

com-petitive position of the food, beverage and pharmaceutical industries. Production costs for biscuits and bread, and candy and syrup, rose by approximately 30% and 60% respectively as a result of the increased sugar prices (World Bank 2005: 4).7

MIT ostensibly attempted to protect sugarcane farmers by permitting imports only for a four-month period outside the milling season (527/MPP/Kep/9/2004), and only on condition that at least 75% of licensees’ raw material originated from local farmers (643/MPP/Kep/9/2002), that the Indonesian Sugar Council deemed domestic production inadequate (527/MPP/Kep/9/2004), and that farmers received at least the minimum guaranteed price (643/MPP/Kep/9/2002). Set at Rp 3,100/kg of refi ned sugar equivalent in September 2002 and increased

subse-7 Presumably these estimates relate to the cost of materials only.

FIGURE 1 Retail Domestic and World Prices of White Sugar, 1997–2004 (Rp/kg)

Source: Data provided by the Ministry of Trade.

1998 2000 2002 2004

0 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000

World Domestic

BIESApr06.indb 98

BIESApr06.indb 98 27/2/06 5:18:07 PM27/2/06 5:18:07 PM

quently to Rp 3,410/kg, the minimum equivalent price paid for domestic sugarcane was, and remains, well above sugar import prices (fi gure 1).

Consequently, there is a signifi cant incentive for sugar import licensees (in

par-ticular, the PTPNs) and associated traders to extract rents by importing low-cost foreign sugar, and even to engage in smuggling, to the detriment of domestic sug-arcane producers. The 73,000 tonnes of sugar imported illegally from Thailand, purportedly under PTPN X’s licence (JP, 17/7/2004, 19/6/2004), was a small por-tion of the estimated 500,000 metric tonnes smuggled in 2003/04 (Ordon and Tho-mas 2004: 32).8

To the limited extent that smallholders are able to sell at the high minimum price for cane, they are still unable fully to capitalise on it, since farmer returns also depend on the average amount of sucrose extracted by the mills over a given period, rather than simply on the quantity of sugarcane delivered. The state-owned mills on Java have low levels of effi ciency, which helps explain the steady

decline of average sucrose extraction rates to less than one-third of the level before World War II, when Indonesia was the world’s second largest exporter.9

While internationally competitive cane is cut only twice and then replanted, smallholders in Java prune the cane up to 12 times during the productive life of the plant, cultivating ratoon (second and subsequent) crops with progressively lower sucrose content. It has been argued that excessive pruning refl ects

substan-tial land preparation costs, high input prices, scarcity of fertiliser, inadequate irri-gation infrastructure, insuffi cient access to timely credit, and the many taxes and

levies imposed by local governments (Asia Foundation and World Bank 2005: 72–5; USDA-ERS 2003: 22). Micro-level trade and agricultural policies directed at alleviating these problems are lacking, but the more fundamental problem is the lack of economies of scale inherent in smallholder cane cultivation on Java. This is a legacy of the 1975 Smallholder Cane Intensifi cation Program (TRI),10 which,

until 1998, formally compelled farmers periodically to cultivate cane.11

Viewed from this perspective, it is unfortunate that the artifi cially high

min-imum price guaranteed under the trade regime (even though partially offset by low sucrose extraction rates) deters smallholders from shifting into higher-yielding agricultural activities: horticulture, vegetables and shrimp farming all offer potentially better opportunities for income growth on Java, according to Athukorala (2002: 157). On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, regulatory intervention generates large excess profi ts to lower cost producers in Lampung

that derive economies of scale from plantation-style cultivation.

Licensed state-owned millers and trading fi rms, and effi cient plantations in

Lampung, appear to have been the primary benefi ciaries of changes in the

regula-tory regime since September 2002, rather than Javanese smallholders. Neverthe-less, representatives of the Java-based APTRI strongly defend the MIT licensing

8 The basis for this estimate is not explained.

9 The marginal recovery of sucrose extraction rates after 1998 has been driven largely by rapid expansion of privately owned plantations in Lampung (Stapleton 2005: 24–8). 10 Presidential decrees 9/1975, Smallholder Sugarcane Development Program, and 5/1998, Discontinuation of Implementation of Presidential Decree No. 5/1997 on the Smallholder Sugarcane Development Program.

11 Irrigated sugarcane cultivation under the TRI system was found to be unprofi table for

farmers for this reason (Nelson and Panggabean 1991: 708–12).

BIESApr06.indb 99

BIESApr06.indb 99 27/2/06 5:18:07 PM27/2/06 5:18:07 PM

100 Tim Stapleton

decrees. This may perhaps be explained by the fact that senior APTRI fi gures have

been linked to sugar traders that profi t signifi cantly from the sugar trade regime,

although these links are fl atly denied by Arum Sabil (personal communication,

9/9/2005). The requirement for APTRI representatives to certify that potential licensees adhere to the 75% domestic procurement criterion prior to licensing (MIT decree 527/MPP/Kep/9/2004) creates a lucrative opportunity to generate rents. APTRI offi cials therefore have a keen interest in the maintenance of the

sugar trade regime, irrespective of the interests of sugarcane farmers.

In implementing restrictive sugar quota licensing systems, Rini Soewandi appears to have been infl uenced heavily by her ministry, which had direct control

over licensing trading activity—and the rents from it. There is no transparency in the allocation and revocation of import licences and inter-island trade licences (regulated by MIT decrees 61/MPP/Kep/2/2004 and 334/MPP/Kep/5/2004) by the trade ministry’s Directorate General of Foreign Trade and Directorate General of Domestic Trade, respectively. These directorates general are afforded signifi

-cant discretion in approving the quantity and timing of each inter-island ship-ment and white sugar import.

Moreover, senior bureaucrats from various ministries dominate the Indonesian Sugar Council (Dewan Gula Indonesia, DGI), which apportions the annual sugar import quota among appointed licensees. The rents that accrue to licensed PTPNs and state-owned trading enterprises are proportional to the amount of sugar they are permitted to import. Authority over quota allocations is therefore likely to be a lucrative asset for bureaucrats in Indonesia’s civil service, where jobs and promo-tions are commonly bought and sold based on the opportunities they present for generating informal income (ADB 2004: 62).

INSTITUTIONAL IMPEDIMENTS TO REFORM

Beyond Tim Tarif there is no formal framework for coordination among economic ministries. This places a signifi cant burden on ministers to negotiate and

coor-dinate policy formulation, so the inclinations of individual ministers are criti-cal. Often from non-political backgrounds, ministers in economics portfolios do not have the advantage of inter-ministerial structures that demand and facilitate cooperation and transparency in policy development. Inadequate mechanisms for inter-ministerial coordination, and for resolution of confl icting policy

prefer-ences among ministries, thus represent a signifi cant obstacle to the development

of a coherent trade regime in Indonesia. As the former fi nance minister, Yusuf

Anwar, has acknowledged, Tim Tarif has been plagued historically by an overly sectoral focus, which has resulted in the formulation of inconsistent and ill-meas-ured policies (MoF decree 71/KMK.010/2005: 1). This is compounded by a lack of expertise and capacity to analyse the opportunity costs of trade policies. In short, the limited capacity of individual ministries to analyse and coordinate policy development effectively is an institutional weakness that enlarges the scope for entrenched interests to capture the policy process.

Sugar trade policy reform is also hindered by the narrow composition of the DGI, which was established during the Soeharto era as a forum for consul-tation on sugar industry problems. The Council is directly responsible to the president, who appoints and dismisses all members. Reformed by Presidential

BIESApr06.indb 100

BIESApr06.indb 100 27/2/06 5:18:07 PM27/2/06 5:18:07 PM

Decree 63/2003 issued by the Megawati government on 11 August 2003, the DGI is dominated by ministers and senior bureaucrats from various ministries. Critically, and in contrast to its composition under Presidential Decree 109/2000 issued by the Wahid government, interest group representation on the DGI’s primary decision-making body is now confi ned to farmer associations (APTRI

and the Indonesian Farmers Association), sugar mills (the Indonesian Sugar Association) and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Unlicensed import-ers, independent experts and consumers (as well as plantation and mill work-ers) no longer have a role on this body, and lack any direct input into sugar trade policy decisions. Direct representation from the food, beverage and pharmaceu-tical industries is similarly foreclosed.

Given the current composition of the DGI, its decisions are inevitably skewed towards rent-seeker interests at the expense of consumers, downstream producers and potential importers. The DGI appears to exemplify the type of institution that privileges groups opposed to reform and denies political representation to groups that would benefi t from it (Keohane and Milner 1996: 250–4). It will be diffi cult for

reform-minded ministers and civil servants to counter -balance entrenched pro-tectionist interests as long as the DGI is overwhelmingly weighted toward per-petuating the status quo on sugar.

Meaningful improvements to the sugar trade policy regime and the sugar industry are therefore unlikely without reform of the DGI itself. The removal of rent-seeking bureaucrats and the inclusion of representatives of downstream producers (such as the Indonesian Food and Beverages Association), unlicensed importers (such as the Indonesian Association of Sugar and Flour Traders and Distributors) and consumer groups on the Council’s primary decision- making body would provide a counterweight to entrenched interests. It is costly for con-sumers to organise independently, and they are commonly ineffective against concentrated producer or trader interests. However, representation of con-sumer groups on the DGI may facilitate the collective projection and defence of consumer interests. In addition, the inclusion of independent experts would enhance the Council’s capacity to analyse policy options for the sugar industry. To allow it to focus on evaluating proposals to lift productivity and improve competitiveness in the industry, the DGI’s infl uence over trade policy could

be confi ned, for example, to advising Tim Tarif and the Minister of Finance on

sugar industry developments that affect the appropriateness of tariff levels and other intervention measures.

As we have seen, individual ministries can circumvent the trade policy deci-sions of others, since no ministry has authority over policy coordination. Moving forward, one ministry—most logically the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs—could be given the mandate to resolve confl icting policy preferences

among ministries on trade and industry policy decisions. Alternatively, a new or existing agency could be given authority to coordinate trade and industry pol-icy making. The trade minister’s current responsibilities could, for example, be expanded to those of a Trade and Productivity portfolio, with authority to coor-dinate all aspects of trade and industry policy, subject to representations by other relevant ministries. Tim Tarif is the body with perhaps the greatest potential to analyse policy alternatives, yet its role is presently confi ned to tariff policies. It

might be worthwhile for this team to be developed into an independent agency

BIESApr06.indb 101

BIESApr06.indb 101 27/2/06 5:18:08 PM27/2/06 5:18:08 PM

102 Tim Stapleton

with responsibility for analysing and publicising the opportunity costs of alterna-tive trade and industrial policies.

However, unless much better analytical expertise is developed within the bureaucracy, institutional reforms in themselves are unlikely to foster the formula-tion of trade policies that uphold the broader public interest. In turn, enhancing the analytical capacity of the bureaucracy may not be feasible in the absence of broader civil service reforms directed at attracting individuals with appropriate skill sets to senior positions in the public service (McLeod 2005a: 154–6; 2005b: 377–82).

CONCLUSIONS

Recent developments in sugar trade policy suggest that even the most determined and reform-minded political leaders are unlikely to prevail unless priority is given to reform of institutional arrangements. The composition of the Indonesian Sugar Council effectively prevents proper consideration of trade policy alternatives, and constitutes a signifi cant barrier to reform of the sugar trade regime and the

sugar industry. By privileging entrenched bureaucrats, import licence holders and traders, and effectively denying representation to groups that would benefi t from

sugar trade policy reform, the framework for policy formulation distorts trade out-comes—as is consistent with the predictions of broader institutional theories on policy making (MacIntyre 2003: 53, 106; Keohane and Milner 1996: 250–4). In effect, institutions such as the DGI can be conceptualised, in Riker’s (1980: 445) terms, as representing ‘congealed preferences’.12 Their re-emergence in recent years is no cause for surprise, nor is it a consequence of democratic reform; rather, they are a throwback to an earlier bureaucratic era.

In the case of sugar regulation (and regulation more generally), democratic proc-esses potentially open the way to a more transparent and balanced consideration of trade and industry policy alternatives. For this to occur, however, the institu-tional framework for trade policy making in Indonesia itself requires reform. Imple-menting and sustaining meaningful sugar trade policy reform in the short term may hinge on the incorporation of a broader cross-section of interests in the DGI and increased transparency in the policy-making process. In the longer term, the strategic formulation of balanced and productivity-improving trade policies will be aided by effective cross-ministerial coordination mechanisms and by building up the capacity to expose and analyse policy alternatives. Until such reforms are implemented, trade policy will continue to be deployed as a redistributive mecha-nism that serves the interests of a well placed few, rather than as a forward-looking instrument operating in the interests of the broader public.

REFERENCES

Abidin, Z. and Ismono, H. (2004) The impact of government policy on the competitiveness of sugarcane farming in Lampung Province, Unpublished paper, University of Lampung, Bandar Lampung.

ADB (Asian Development Bank) (2004) Country Governance Assessment Report, Republic of Indonesia, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

12 In essence, ‘congealed preferences’ are policy preferences that are served and perpetu-ated by an institutional structure.

BIESApr06.indb 102

BIESApr06.indb 102 27/2/06 5:18:08 PM27/2/06 5:18:08 PM

Asia Foundation and World Bank (2005) Improving the Business Environment in East Java: Views from the Private Sector, Jakarta.

Athukorala, P. (2002) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Stud-ies 38 (2): 141–62.

Basri, C. and Hill, H. (2004) ‘Ideas, interests and oil prices: the political economy of trade reform during Soeharto’s Indonesia’, The World Economy 27 (5): 633–55.

Basri, C. and Soesastro, H. (2005) ‘The political economy of trade policy in Indonesia’,

ASEAN Economic Bulletin 22 (1): 3–18.

Boediono (2005) ‘Managing the Indonesian economy: some lessons from the past’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (3): 309–24

Iqbal, M., Rusastra, W. and Suprihatini, R. (1999) ‘The sugar development strategy with an economic crisis and competitive markets’, Australian Centre for International Agricul-tural Research (ACIAR) Indonesia Research Project Working Paper 99.19: 1–29. Keohane, R. and Milner, H. (1996) Internationalisation and Domestic Politics, Cambridge

Uni-versity Press, New York.

Liu, M.-C. (2002) ‘Determinants of Taiwan’s trade liberalization: the case of a newly indus-trialized country’, World Development 30 (6): 975–89.

MacIntyre, A. (2003) The Power of Institutions: Political Architecture and Governance, Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London.

MacIntyre, A. and Resosudarmo, B. (2003) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 39 (2): 133–56.

Marks, S. (2004) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

40 (2): 151–75.

McLeod, R. (2005a) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

41 (2): 133–56.

McLeod, R. (2005b) ‘The struggle to regain effective government under democracy in Indo-nesia’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (3): 367–86.

Nelson, G. and Panggabean, M. (1991) ‘The costs of Indonesian sugar policy: a policy anal-ysis matrix approach’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics 73 (3): 703–12.

Ordon, D. and Thomas, M. (2004) ‘Agricultural policies in Indonesia: producer support estimates 1985–2003’, MTID (Markets, Trade, and Institutions Division) Discussion Paper No. 78, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington DC.

Riker, W. (1980) ‘Implications from the disequilibrium of majority rule for the study of institutions’, American Political Science Review 74: 432–46.

Stapleton, T. (2005) The political economy of Indonesian trade policy: the case of sugar, available at: http://members.optusnet.com.au/stapes/PolEcoIndoSugarTradePolicy.pdf. USDA-ERS (Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture) (2003) ‘World

Sugar Policy Review’, in Sugar and Sweeteners Outlook/SSS-236/31 January.

World Bank (2005) ‘Regaining Competitiveness’, Indonesia Policy Brief, World Bank, Jakarta. WTO (World Trade Organization) (2003) Trade Policy Review Indonesia: Minutes of

Meet-ing Addendum, WT/TPR/M/117/Add.1, WTO Trade Policy Review Body, 11 Septem-ber 2003: 1–105.

BIESApr06.indb 103

BIESApr06.indb 103 27/2/06 5:18:08 PM27/2/06 5:18:08 PM