Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ubes20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:26

Journal of Business & Economic Statistics

ISSN: 0735-0015 (Print) 1537-2707 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ubes20

Comment

Søren Johansen

To cite this article: Søren Johansen (2004) Comment, Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 22:2, 169-172, DOI: 10.1198/043500104000000046

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1198/043500104000000046

Published online: 01 Jan 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 38

application to many public policy questions regarding bank su-pervision and regulation. However, given the differing concerns of monetary policy, we are less certain that the GVAR model would be as useful for this purpose. Aside from the fact that most central banks do not currently model global economic fac-tors directly, their current emphasis on policy simulations limits the GVAR model’s usefulness, due mainly to its atheoretic na-ture. Furthermore, although the model’s limited dynamic struc-ture should not overly hamper its usefulness with respect to credit risk concerns, it probably would limit its usefulness for macroeconomic analysis and policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Federal Reserve System. These comments were prepared for presentation at the 2003 meeting of the American Statistical Association. The authors thank Alastair Hall for the opportunity to discuss the article and Anita Todd for editorial assistance.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Allen, L., and Saunders, A. (2003), “A Survey of Cyclical Effects in Credit Risk Measurement Models,” Working Paper 126, Bank for International Settlements.

Amato, J. D., and Furne, C. H. (2003), “Are Credit Ratings Procyclical?” Working Paper 129, Bank for International Settlements.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2003), “The New Basel Capital Ac-cord,” manuscript, Bank for International Settlements.

Berkowitz, J. (2000), “A Coherent Framework for Stress Testing,”Journal of Risk, 2, 1–11.

Blume, M. E., Lim, F., and MacKinlay, A. C. (1998), “The Declining Credit Quality of U.S. Corporate Debt: Myth or Reality?”Journal of Finance, 53, 1389–1413.

Borio, C., Furne, C., and Lowe, P. (2001), “Procyclicality of the Financial System and Financial Stability: Issues and Policy Options,” Working Paper 1, Bank for International Settlements.

Carey, M. (2002), “Some Evidence on the Consistency of Banks’ Internal Credit Ratings,” manuscript, Board of Governors, Federal Reserve System. Clarida, R., Gali, J., and Gertler, M. (1999), “The Science of Monetary

Pol-icy: A New Keynesian Perspective,”Journal of Economic Literature, 37, 1661–1707.

Laxton, D., Isard, P., Faruqee, H., Prasad, E., and Turtleboom, B. (1998), “MULTIMOD Mark III: The Core Dynamic and Steady-State Models,” Occasional Paper 164, International Monetary Fund.

Lopez, J. A. (2003), “The Empirical Relationship Between Average Asset Cor-relation, Firm Probability of Default and Asset Size,”Journal of Financial Intermediation, forthcoming.

Lucas, R. (1976), “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique,” inThe Phillips Curve and Labor Markets, eds. K. Brunner and A. Meltzer, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 19–46.

McKibbin, W., and Sachs, J. (1991),Global Linkages: Macroeconomic In-terdependence and Cooperation in the World Economy, Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

Pagan, A. (2003), “Reections on Some Aspects of Macro-Econometric Modelling,” invited lecture to the African Econometrics Conference, Stellenbosch.

Pesaran, M. H., Schuermann, T., Treutler, B.-J., and Weiner, S. M. (2003), “Macroeconomic Dynamics and Credit Risk: A Global Perspective,” man-uscript, University of Cambridge.

Sims, C., and Zha, T. (2002), “Macroeconomic Switching,” manuscript, Prince-ton University.

Treacy, W. F., and Carey, M. (2000), “Credit Risk Rating Systems at Large U.S. Banks,”Journal of Banking and Finance, 24, 167–201.

Wagster, J. D. (1996), “Impact of the 1988 Basel Accord on International Bank-ing,”Journal of Finance, 51, 1321–1346.

Comment

Søren J

OHANSENDepartment of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 5, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark

1. INTRODUCTION

When building a global model of the economy, the main empirical problem is that by including many countries and many variables from each country and allowing them to inter-act arbitrarily via, for instance, a cointegrated VAR, produces an overwhelming amount of parameters to t. This is simply not possible in the sense that asymptotic inference is no longer reliable and the cointegrating relations are difcult to identify. In this sense we are asking too much. We must model the possi-ble interactions in some other way, which entails compromises. It is these compromises and their consequences that are the fo-cus of these comments.

My main points are that the problem faced is of importance and must be addressed, and all attempts to solve it are welcome, but the nature of the compromises rst needs to be discussed so we can get a feeling for the reliability of the results.

The authors are to be congratulated for attempting to present a possible solution to this problem. Their main new idea is to

build a global model from individual country models, by allow-ing cointegration with other countries to appear only through country-specic indices for the rest of the world. In this way this model represents an innovation compared with the many empirical analyses of one, two, or three countries only.

2. THE GLOBAL MODEL

The main, and very nice, idea is that the long-run relations or steady-state relations in the world economy can be expressed as relations between national variables and an index for the (country-specic) rest of the world. The price paid for this property is that any two countries can cointegrate only via these indices.

© 2004 American Statistical Association Journal of Business & Economic Statistics April 2004, Vol. 22, No. 2 DOI 10.1198/043500104000000046

Suppose, for instance, that we have only four countries, and that the variables include the prices measured in the same currency. Assume that prices in country one and country two cointegrate with the index for prices in the rest of the world; that is, we have the two relations

p0t¡c0.w01p1tCw02p2tCw03p3t/»I.0/

and

p1t¡c1.w10p0tCw12p2tCw13p3t/»I.0/:

In this case the prices in the two countries can cointegrate only if we can nd coefcientsa0anda1, so that by taking the linear combination with these weights, we can eliminatep2tandp3t,

that is,

In general, this will be possible only fora0Da1D0, but if

.w02;w03/D¸.w12;w23/;

so that in a sense the two extra countries enter in a proportional way, then we can takea0Dc1anda1D ¡¸c0:

If, however,p2also cointegrates with its world index, then

p2t¡c2.w20p0tCw21p1tCw23p3t/»I.0/;

which can always be found. Thus countries can cointegrate if the remaining countries enter in proportional ways or in suf-ciently many relations.

They cannot enter in too many relations, however, because ifp3also cointegrates with its world index, then

p3t¡c3.w30p0tCw31p1tCw32p2t/»I.0/;

and the results can be collected in

0

In general, this matrix has full rank, which implies that pit is

stationary foriD0;1;2;3, which is not usually found in data. If, however,ciD1,iD0;1;2;3;then the matrix is singular

and all spreadspit¡pjt become stationary, so that purchasing

power parity holds between all countries. This is only three in-dependent relations, however. Thus the four cointegrating rela-tions we get by just adding the country-specic cointegration ranks reduce in this particular case to three for the system to describe nonstationary price variables. This has implications for the discussion in Section 4 on the properties of the global model, and also in the application where the rank of the global system is set to rDPN

iD0ri, despite the extra near-unit root

of .9456.

3. IMPULSE RESPONSE ANALYSIS

Impulse response analysis is a way of gaining insight into the dynamic properties of the system. We give a shock to the system and follow the effect of the shock over time. This is studied in Section 6. Instead of shocking individual variables, or making attempts to interpret suitable orthogonal shocks as “structural” economic shocks, using the so-called “generalized impulse” shocks is recommended. These are dened as the av-erage “historical” shocks of the form

ciDE¡"tje0

whereeiis a unit vector; that is, the shocks are dened by

shift-ing a given variable by 1 standard deviation and all of the others by the expected value of"tgiven this choice.

For a cointegrated VAR model,

1XtD®¯0Xt

¡1C011Xt¡1C"t; "tiid.0;Ä/;

the effect of such a shockcigiven at timetto the system on the

value of the process attCh;is found from the Granger repre-sentation

by partial differentiation with respect to"tin the directionci,

@Xt

Ch

@"t

.ci/D.CCCh/ci; hD0;1; : : : :

Thus the effect is partly a long-run permanent effect,Cci, and

partly a transitory effect,Chci, which tends to 0.

Up to a factor.e0

iÄei/¡1=2, the generalized impulse shocks

are the columns of the variance matrix Ä. To illustrate this idea, take a stylized example with yUSt Dlog.GDPUS/t and yUKt Dlog.GDPUK/t;where the variance matrixÄof the

resid-uals could be (in some arbitrary units)

ÄD

One could ask about the effect over time of a shock toyUSt with-out shockingyUKt , but instead we investigate the effect of a shock of the form

Note that historically a shock to the U.S. has been accompanied by a shock to the U.K., that is, the shocks are correlated, and in fact on average the shock to the U.K. is larger than the shock to the U.S. This is a consequence of the denition, but the question is in what sense this is a shock to the U.S.; it seems more like a shock to the U.K., because this is in fact larger.

As an example, Figure 2 shows that a negative (¡1¾ /shock to the U.S. real equity prices seems to have the strange per-manent positive impact on real output in the U.K. (and China) of .2% in the long run. It could be the case that when using the generalized shock to the U.S., one is in reality shocking the U.K. more and perhaps in some other direction, depend-ing on the value of the covariance. Therefore, the nature of the suggested shocks seems to be not quite as obvious as the term suggests.

4. THE MATHEMATICAL ASSUMPTIONS

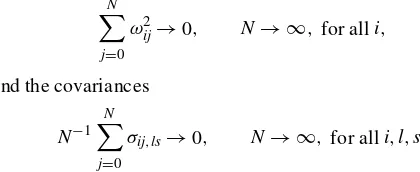

Section 7 outlines the author’s mathematical assumptions. The assumptions are the usual ones on the eigenvalues of the global model, and the new ones are on the weights

N

There is also a condition of weak exogeneity, and one could add the obvious condition of parameter constancy in the period under consideration.

The conditions sufce for cov.x¤it; "it/to tend to 0, but there

it stops. IfN! 1, then the number of parameters increases; this is usually the situation where maximum likelihood is not working and where special theorems must be established for making valid inference.

So a natural question is what exactly are the mathematical results on asymptotic distributions that can be obtained in this framework. There should be results forNandT tending to1.

On a more practical matter, in the applicationND11, which is not necessarily very big, and weights of the size of 2=3 (see Table 2), which do not appear small. No details are given about the cross-correlations.

Instead of discussing whether these values are sufciently large to justify asymptotic theory, it is probably more helpful to discuss whether one could develop corrections that would take into account the actual values of the quantitiesthat are supposed to be either 0 or1:

The authors discuss small-sample problems for the rank test statistics, but for the trace tests I have in fact worked out a cor-rection factor that would possibly be a good idea to use in view of the moderate value ofTD80:

The assumption for which I am most worried about the consequences is that of constant parameters in the period 1979Q1–1999Q1, that is, 20 years of quarterly data, giving T D80. I am sure that one can nd major political events that change the economic and statistical models in the period 1979–1999. This casts doubt on the assumption of constant pa-rameters, which is implicit in the analysis. Not many applied researchers nd constant parameters when performing analy-sis of either single country or pairs of countries. Disregarding this can have disastrous effects on the impulse response analy-ses, which can also change completely if the wrong lag length is chosen.

The authors perform many tests for misspecication, includ-ing lag length and weak exogeneity, and there is not a lot of overall evidence that the decisions made are against the data. Still, one feels uneasy about this summary treatment of many countries, and in particular the assumption of constant parame-ters is not checked.

It is possible to dismiss such qualms as nit-picking, and I am reasonably sympathetic with that standpoint, because the scope of the whole investigation is to paint with a broad brush and look at solutions rather than problems. But we must then at least

follow up the analysis by a sensitivity analysis of the conclu-sions to a break down of the various assumptions. I would of course prefer to develop asymptotic (and nite sample) results that are less demanding on the statistical properties of the data. I am thinking in particular of the assumptions of stationarity of the differences of the data, the so-called “I.1/assumption.” There ought to be limit theorems that state that even if the dif-ferences are not exactly stationary but have deterministic breaks and possibly nonconstant parameters or strange deterministic terms, the basic asymptotics should still hold.

The reason that I brought this up is that I do not believe that such theorems can be found. We have looked at many cases where the deterministics change during the period and found that for each special case we need new limit theorems; that is, the fact that the differences are not quite stationary, or only so in subperiods, has serious implications for asymptotic results and hence need to be modeled. In this respect, the article offers a host of problems that remain for later contributions to work out in detail.

5. WEAK EXOGENEITY

The weak exogeneity property of the model is necessary for making inference on the partial models, not just to get efcient inference, but also to make asymptotic inference free of nui-sance parameters. The weak exogeneity of the oil price, which means that the oil price does not react to a disequilibrium error in any of the world economies, is tested in the application.

In modeling a single economy, one can sometimes assume this, even though assuming it for the U.K. has created much discussion, as I know from personal experience. The authors state that they want to model it as weakly exogenous for the whole world economy with the argument that it is “geopolitical factors” that determine oil prices. The authors nd that the only country for which it seems to be invalid is the U.S. and decide to assume it anyway. Why is this so important to assume? Why not let it be endogenous for the U.S. model? After all, they are involved in geopolitical factors. Are you not worried about the consequences for the impulse response functions of incorrectly assuming weak exogeneity?

6. THE MODEL–FREE ESTIMATOR

In the section on the risk of a portfolio, I noticed that the so-called “model free” estimator of the variance, var.r/, was given as

leaving out some indices. There are some assumptions un-derlying this that could be explicitly stated. To take a simple example, if rt is generated by rt D½rt¡1C¹C½t, then for

The usual decomposition

T X

iD1

.rt¡¹/2D T X

iD1

.rt¡ Nr/2CT.Nr¡¹/2

shows that

E Á T

X

iD1

.rt¡ Nr/2 !

» ³

T¡1C½ 1¡½

´ var.r/;

so that a better estimator of the var.r/would be

1

T¡.1C½/=.1¡½/

T X

iD1

.rt¡ Nr/2:

The question now is how large is ½. Just as a warning, if ½D:95, then 11C½

¡½ D39, and with T D80, there is a serious

bias in using the factor.T¡1/¡1. Usually returns are not that predictable from the past, but eq. (69) seems to indicate pre-dictability from macro variables that are usually predictable from the past. Hence the “model-free” estimate should perhaps be used only if the predictability is small.

7. CONCLUSION

I nd the idea behind the GVAR model fascinating and points to a possible path toward a satisfactory answer to the problem of modeling the whole world. But the ideas in the article seem also to point to a number of problems that must be addressed in the future.

Comment

Kenneth F. W

ALLISDepartment of Economics, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, U.K. (K.F.Wallis@warwick.ac.uk)

Pesaran, Schuermann, and Wiener have proposed a new ap-proach to global economic modeling in their GVAR model. Their article contains a clear exposition of the modeling princi-ples that they espouse and the theoretical and practical problems that they have had to solve in implementing their approach. In addition to its intellectual contribution, the article represents a heroic data organization and management effort. It concludes with an application in which forecasts generated by an illus-trative GVAR model feed into a credit risk management prob-lem. This comment focuses on some econometric modeling and forecasting questions from a comparative standpoint, to help place the present contribution in a broader context. The com-ment draws on recent comparative research on multicountry models (Mitchell, Sault, Smith, and Wallis 1998; Wallis 2003), together with similar research on models of the U.K. economy (Jacobs and Wallis 2003) that includes the model of Garratt, Lee, Pesaran, and Shin (2000, 2003a) referred to by the authors.

GLOBAL ECONOMIC MODELS

Currently operating global models include the NiGEM model and the IMF’s MULTIMOD (Laxton, Isard, Faruqee, Prasad, and Turtelboom 1998), mentioned by the authors. Other multicountry models that have featured in the compar-ative research referred to earlier, along with these two, are the MSG2 model (see McKibbin and Sachs 1991), forerun-ner of the G-Cubed model (McKibbin and Wilcoxen 1999), and the QUEST model of the European Commission (Roeger and in’t Veld 1997). These models can be taken as typical modern-day representatives of the mainstream structural global modeling tradition to which the present authors seek an alter-native. Like the GVAR model, each of them is constructed, maintained, developed and used by a single research team, un-like Project LINK, mentioned by the authors, which, moreover,

was never a continuously operational system in the same sense. Also like the GVAR model, they contain separate models of national economies of central interest, then aggregate the re-maining economies into various groups. The basic Mark III version of MULTIMOD, for example, contains separate mod-els for each of the G-7 countries—the U.S., Canada, Japan, France, Germany, Italy, and the U.K.—and for an aggregate grouping of 14 smaller industrial countries; the rest of the world is then aggregated into two separate blocks of devel-oping and transition economies. The GVAR model comprises a similar number of submodels, whereas NiGEM and QUEST are more disaggregated.

The mainstream multicountry models were developed from national economy models to facilitate the study of macroeco-nomic interactions among nations, principally the transmis-sion of the effects of economic policy. To this end, explicit modeling of linkages through trade and nancial ows is un-dertaken. Each country model is a structural model in the tradi-tional sense, representing the behavior of households,rms, and the government and the markets in which they interact. Flows cumulate into stocks, and consistent global modeling requires that trade balances and net foreign asset positions sum to 0 at all times. The complete national economy submodels typi-cally have a common theoretical structure, whereas the remain-ing blocks are modeled in much less detail, focusremain-ing on trade and payments in a more reduced-form than structural manner. Whereas some models are engaged in real-time forecasting, others eschew forecasting and concentrate exclusively on pol-icy analysis.

© 2004 American Statistical Association Journal of Business & Economic Statistics April 2004, Vol. 22, No. 2 DOI 10.1198/073500104000000055