Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Critical Incidents Approach to Outcomes

Assessment

Peter Bycio & Joyce S. Allen

To cite this article: Peter Bycio & Joyce S. Allen (2004) A Critical Incidents Approach to Outcomes Assessment, Journal of Education for Business, 80:2, 86-92, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.80.2.86-92

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.2.86-92

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 33

View related articles

he agencies responsible for accred-iting programs in higher education (e.g., International Association for Man-agement Education, AACSB [2001]) increasingly have been requiring evi-dence that universities are fulfilling their stated missions. When designing out-comes assessment programs to help meet the requirements of these agencies, universities face challenging decisions concerning the particular types of assessments to be used (DeMong, Lid-gren, & Perry, 1994). Some methods, such as student–teacher portfolios (Seldin, 1997) and the Educational Test-ing Service (ETS) Major Field Test in Business (Allen & Bycio, 1997) are intended to directly assess specific aspects of student learning. Others, such as the College Student Experiences Questionnaire (CSEQ; Pace & Kuh, 1998) are designed to elicit student opinions concerning a wide range of aspects of their university experiences.

When the assessment option chosen relies on student opinions, a wide range of issues associated with the validity of self-reported data come into play. A review of the literature by Schwarz (1999), for example, revealed that self-reports can differ dramatically as a result of (a) question context, (b) ques-tion wording, (c) the response scale used, and (d) the order in which ques-tions are asked.

The concerns raised by Schwarz (1999) have potential applicability to the interpretation of standardized question-naires such as the 169-item CSEQ. Ques-tionnaires of this type address a compre-hensive range of issues, including the general university environment and esti-mates of educational gains. One can eas-ily collect CSEQ data from large num-bers of students and directly compare the results with those of other schools. On the other hand, the standardized aspect of the CSEQ implies that student responses must be interpreted within the question-naire context.

The rater bias traditionally referred to as the halo effectis an example of a con-textual issue (Hoyt, 2000, among oth-ers). Specifically, the interpretation of the CSEQ can be ambiguous because most of the items refer to “the college.” This makes it difficult to determine whether the results reflect the university as a whole, the business college, the particular business major, or some com-bination of all three.

One method of obtaining a sense of the relative prominence of the depart-ments, colleges, and university from the student perspective is to supplement standardized questionnaire feedback with an open-response format. Schwarz (1999) noted the potential for dramati-cally different self-reported results from different response formats. For exam-ple, when parents were presented with a list and asked to rate “the most impor-tant thing for children to prepare them for life,” 61.5% picked “to think for themselves.” Yet, when asked the same question without a list of items to choose from, only 4.6% of parents iden-tified a similar theme (Schuman & Presser, 1981, pp. 105–107). Findings such as these raise the following ques-tion: In the absence of a standard list of items, what would student feedback mean to universities?

While considering the potential bene-fits of open-response formats, we

A Critical Incidents Approach to

Outcomes Assessment

PETER BYCIO JOYCE S. ALLEN

Xavier University Cincinnati, Ohio

T

ABSTRACT. Standardized ques-tionnaires often have been used to elicit student opinions on issues regarding accreditation by the Asso-ciation to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business—International (AACSB). These questionnaires require students to rate a wide range of items that may or may not be important to them. In this study, the authors supplemented these question-naires by asking graduating business students to evaluate their university experiences by describing aspects that were especially successful and factors that needed improvement. This open-format, “critical incidents” approach to outcomes assessment readily generated recollections of incidents useful in guiding program change. The incidents provided addi-tional perspective on data obtained from the College Student Experi-ences Questionnaire.

thought of a concept from the human resource management literature— criti-cal incidents. Originally described by Flanagan (1954), critical incidents essentially are stories that reflect espe-cially good or bad performance by an incumbent on a job. Ideally, they are specific, describing what the incumbent did, the context of the behavior, and its consequences. When large numbers of critical incidents are collected for a tar-get job (e.g., college instructor), the information aids in the development of management tools including job descriptions, training materials, and performance-appraisal systems (Bow-nas & Bernardin, 1988).

There are many reasons to suspect that critical incidents can yield useful supple-mental outcomes-assessment informa-tion. First, by definition, the feedback is critical. When examining a lengthy ref-erence period, respondents likely will focus on significant, nonmundane events (Schwarz, 1999). Second, compared with standardized questions providing a wide range of cues, the critical-incidents approach is more likely to indicate aspects that immediately come to mind about the college experience. Finally, to the extent that students are able and will-ing to provide them, critical incidents should offer more detail compared with standardized questionnaire ratings. For example, the following critical incident would be applicable to our university environment:

I often arrive at the university after 9:00 a.m. Many times there are no parking spots available. In one case, I had to park a mile or two from campus and did poorly on an exam because I was late to class.

If many incidents similar to this one emerged, the institution likely would conclude that parking was a student concern.

Although parking per se is of little interest from an accreditation perspec-tive, the institution using this approach would look for an overall pattern of inci-dents in line with areas of university focus. Importantly, whatever the specific pattern of results, critical incidents should reflect what the students are thinking without prompting from more structured formats.

Our purpose in this study was to examine the value-added in asking

busi-ness students who were near graduation to generate critical incidents based on their university experiences. Although our study was exploratory, we sought to examine at least three issues of interest. First, given the relatively open-ended assessment format, we wondered how many useful critical incidents the aver-age student would provide. A second area of interest involved the relative per-centages of incidents that would be related to the university, business col-lege, and business major. Finally, a question of obvious interest concerns the degree to which the critical-incidents content would correspond to data obtained from the CSEQ. A comparison was possible because an independent university-level mailing of the CSEQ had been conducted.

Method

Sample

During the final regular class meet-ing, we asked students in the undergrad-uate and gradundergrad-uate business capstone courses during spring 1999 to provide critical incidents. We surveyed all five capstone undergraduate offerings for a potential sample size of 105. We used 7 of the 8 MBA capstone courses, for a potential sample of 189 (one MBA pro-fessor forgot to administer the form). Because the capstone was the final pro-gram requirement, the respondents typi-cally were very near graduation.

Independently, the university mailed the CSEQ to all undergraduates who completed their degree program during the 1998–1999 academic year. The uni-versity’s potential sample of 122 busi-ness majors was slightly larger than our critical-incidents undergraduate group (n= 105), because it had included fall 1998 graduates. The university received 86 responses from business majors for a 70% response rate.

Critical Incidents Form: Administration and Analysis

The critical incidents form first asks students to think back over their expe-riences regarding the courses and the advising and general services that they received. Then they are asked to

pro-vide (a) up to three examples of things that they believed that a department, the college, or the university did well (Part A) and (b) up to three examples of things that the same groups did poorly (Part B). To give students a better understanding of the level of informa-tion requested, we presented them with the critical-incident example pertaining to parking noted earlier. We adminis-tered the critical-incidents forms in the same way that we treated teaching eval-uations: The instructor was not present while the students completed the forms, and a student was asked to col-lect the forms and return them to either the office of a department chair or to the dean.

One of us (the senior author of this article) read and counted the critical incidents. We then created content cate-gories appropriate to the responses. Very few of the responses were ambigu-ous. We placed critical incidents that were relatively idiosyncratic or unclear in a “miscellaneous” category.

We used ttests for dependent samples for statistical comparisons of the num-ber of college, department, and univer-sity incidents provided. We performed analysis of variance to examine the pos-sibility of differences by program (i.e., undergraduate and MBA).

The CSEQ

As noted earlier, the CSEQ (Pace & Kuh, 1998) is a standardized survey that asks students about a wide range of issues. These include college activities (e.g., experiences with faculty members and campus facilities), the college envi-ronment (e.g., emphasis on the develop-ment of scholarly and intellectual quali-ties), and estimates of gains from the college experience (e.g., the ability to write clearly or the ability to learn on own’s own).

Critical Incidents and CSEQ Correspondence

Given that the collection of critical incidents was exploratory and that the CSEQ had been administered and ana-lyzed independently by another unit of the university, we had little a priori idea of the degree to which these two forms of

assessment would correspond. At a mini-mum, we intended to examine the CSEQ for items and dimensions aligned with meaningful clusters of critical incidents.

Results

Response Rate

At the undergraduate level, 64 of the originally registered 105 (61%) students completed the form. The response rate among MBAs was 55% (105 of 189 original registrants). These response rates reflect less-than-perfect class attendance as well as the tendency for some students to drop the course as the semester progressed.

Quantity and Distribution of Critical Incidents

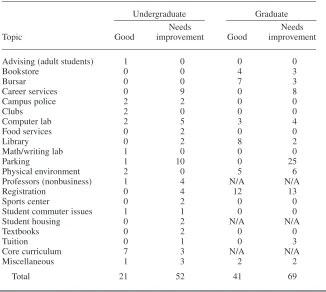

Neither group of students had diffi-culty with the open-ended format. The average undergraduate respondent gen-erated 4.42 critical incidents for a total of 284. MBAs provided 486 incidents, an average of 4.62 per student. The overall ratio of positive-to-negative inci-dents was close to 50/50. In Table 1, we present data pertaining to the number of critical incidents generated for the col-lege, department, and university.

As the data in Table 1 show, there was a tendency for both undergraduate (t = 2.39,p< .02) and master’s degree (t = 2.25,p< .03) students to report signifi-cantly more college-related incidents than department-related ones. Similarly, undergraduates (t = 2.98 p < .01) and master’s degree (t = 5.68, p < .01) respondents provided significantly more incidents that referred to the college than university-related incidents. Mas-ter’s degree students differed from undergraduates only in that they provid-ed significantly more (t= 2.89,p< .01) department-related incidents compared with university-related ones.

Critical Incidents Content

In Table 2, we display the categories and frequency of responses relating to the business college and its depart-ments, and in Table 3 we show similar information for the university as a whole. A broad range of issues were

TABLE 1. Number of Critical Incidents Generated per Student

College Department University

M SD M SD M SD

Undergraduate 1.98a 1.67 1.30b 1.52 1.16b 1.31

Graduate 2.09a 1.55 1.56b 1.63 .97c 1.23

Note. For undergraduates,n= 64; for graduates,n= 105. Means with different letters were signif-icantly different at the p< .01 level.

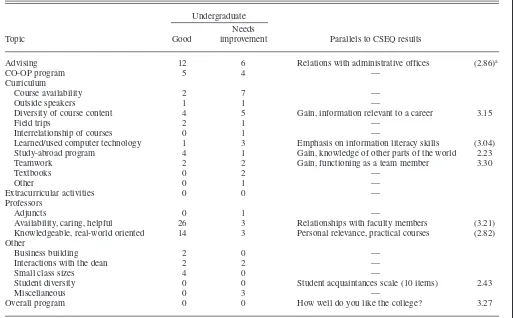

TABLE 2. Content and Quantity of College of Business and Department-Based Critical Incidents

Undergraduate Graduate

Needs Needs

Topic Good improvement Good improvement

College of business

Advising 12 6 22 11

CO-OP program 5 4 N/A N/A

Curriculum

Course availability 2 7 27 20

Outside speakers 1 1 0 2

Diversity of course content 4 5 7 7

Field trips 2 1 0 0

Interrelationship of courses 0 1 5 8

Learned/used computer

technology 1 3 0 8

Study-abroad program 4 1 N/A N/A

Teamwork 2 2 6 8

Textbooks 0 2 0 2

Other 0 1 0 8

Extracurricular activities 0 0 0 6

Professors

Adjuncts 0 1 4 4

Availability, caring, helpful 26 3 16 5

Knowledgeable, real-world

oriented 14 3 18 2

Other

Business building 2 0 0 0

Interactions with the dean 2 2 0 0

Small class sizes 4 0 0 0

Student diversity 0 0 3 0

Miscellaneous 0 3 1 2

Overall program 0 0 6 12

Total 81 46 115 105

Departments

Accounting 9 3 18 4

Information systems 1 3 5 12

Economics and HR 6 8 11 5

Finance 7 3 23 10

Management 3 8 37 21

Marketing 16 16 12 6

Total 42 41 106 58

raised in the critical incidents, some expected (e.g., incidents related to pro-fessors and curriculum) and others more surprising (e.g., cases regarding the campus police and food services). It was interesting to note that the content areas were very similar for undergradu-ates and MBA students.

The pattern of critical-incidents fre-quencies in Table 2 shows that the undergraduate students perceived the business college as having a very clear strength. Specifically, 26 of the 64 stu-dents made reference to available, car-ing, and/or helpful faculty members in the critical incidents reported. More-over, a relatively high number (14) referred to business professors as being knowledgeable and real-world oriented. Similarly, more than half of the positive department-specific incidents (23 of 42) referred to particular professors. There was less consensus regarding the areas needing improvement (see Table 2). Even the most frequently cited issue, course availability, was addressed in only 7 incidents.

Areas of strength were evident in the pattern of responses from master’s degree students, although these differed

somewhat from the areas of strength noted by undergraduates. Our 105 MBAs regarded course availability (27) and advising (22) as the top strengths, whereas they perceived knowledge (18) and availability of faculty members (16) as secondary strengths. On the other hand, like the undergraduates, the MBAs referred to specific professors in almost half (50 of 106) of their positive department-specific incidents.

As with the undergraduates, there was less consensus among MBAs con-cerning areas needing improvement. The most frequently cited concern was course availability. On the surface, it struck us as odd that course availability would be considered both a strength (27) and a weakness (20) (see Table 2). However, this pattern revealed that our MBAs, more that 90% of whom were part-time students, appreciated the opportunity to take courses on evenings and weekends and during the summer. Still, like some of the undergraduates, they wanted even more choice regarding the specific days and times.

One aspect of our findings not reflected in Tables 2 or 3 relates to the level of detail and, in some cases, the

colorful language provided by students in the incidents. On the positive side, there were stories about specific faculty members who stayed late in the evening or came in on a weekend to hold study sessions or to counsel individuals who were starting small businesses. On the other hand, there were occasional inci-dents in which stuinci-dents felt “blown off” by a professor or an administrator who, for example, barely looked at the course schedule proposed by a student during preregistration.

Many issues were more programmatic than interpersonal. For example, more than half of the positive critical incidents regarding the management department at the MBA level concerned the use of a multifaceted global computer business simulation. A similar percentage of neg-ative stories concerned inappropriate overlap among the management courses.

Correspondence Between the Critical Incidents and CSEQ Results

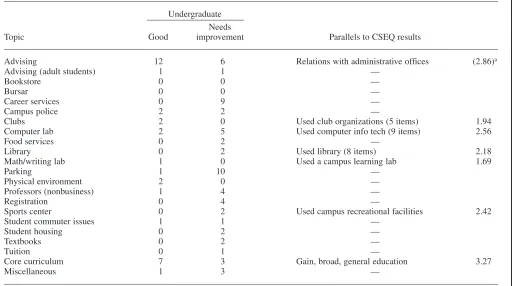

In Tables 4 and 5, we show the rela-tionship between the critical incidents content and the CSEQ for college and university issues. We limited this com-parison to the undergraduate sample because the university did not mail the CSEQ to MBA students.

The data in Table 4 show that the majority of critical incidents regarding the business college (90 of 127, 71%) were related, at least indirectly, to CSEQ content. The main areas lacking a CSEQ link were the co-op program and course availability, each of which yielded 9 incidents. In most cases, the links or lack thereof were quite clear. Besides comparing content correspon-dence per se, we also compared the strength of CSEQ ratings with the rela-tive percentages of posirela-tive and negarela-tive incidents in a given category. Although the CSEQ employs a mix of 4- and 7-point response scales, we converted all the findings to the 4-point metric for ease of comparison.

In some cases, high percentages of positive incidents (e.g., those referring to available, caring, and helpful professors) were associated with relatively high CSEQ ratings (e.g., 3.21 for relation-ships with faculty members). On the other hand, there were cases of poor

TABLE 3. Content and Quantity of University-Based Critical Incidents

Undergraduate Graduate

Needs Needs

Topic Good improvement Good improvement

Advising (adult students) 1 0 0 0

Bookstore 0 0 4 3

Bursar 0 0 7 3

Career services 0 9 0 8

Campus police 2 2 0 0

Clubs 2 0 0 0

Computer lab 2 5 3 4

Food services 0 2 0 0

Library 0 2 8 2

Math/writing lab 1 0 0 0

Parking 1 10 0 25

Physical environment 2 0 5 6

Professors (nonbusiness) 1 4 N/A N/A

Registration 0 4 12 13

Sports center 0 2 0 0

Student commuter issues 1 1 0 0

Student housing 0 2 N/A N/A

Textbooks 0 2 0 0

Tuition 0 1 0 3

Core curriculum 7 3 N/A N/A

Miscellaneous 1 3 2 2

Total 21 52 41 69

agreement that reflected differences in the assessments. For example, four stu-dents reported very positive study-abroad experiences, with the only nega-tive being that more such opportunities should be offered, yet the CSEQ item reflecting student-rated gains in knowl-edge of other parts of the world was only 2.23. Thus, although the CSEQ data indicate overall relative weakness in this area, the critical-incidents responses revealed the very positive experiences of a small group. Analogous examples of the assessments yielding different infor-mation included the application and use of computer technology.

Among the university-related critical incidents, only 28% of the content (24 of 74 incidents) corresponded to items in the CSEQ (see Table 5). Parallels were lacking for concerns regarding parking, career services, campus police, and registration, among others. Also, much like the study-abroad example in the business college, CSEQ ratings for

specific university services could be quite low (e.g., 1.69 for “used a campus learning lab” and 1.94 for clubs and organizations), even though some stu-dents found this category very memo-rable and valuable.

Discussion

Usefulness of Critical Incidents for Outcomes Assessment

Critical-incidents information has helped us focus both our college and department resources on issues that are especially important and memorable to students. For example, we have used clusters of incidents (good and bad) involving business college staff as a basis for feedback during performance evaluations. Another example involved the formation of a department commit-tee in response to a critical-incidents cluster concerning undue overlap among MBA-level management courses. We

subsequently made substantial adjust-ments to one of the courses, and the issue no longer surfaces in our assess-ments. These examples illustrate how critical-incident content can be used for continuous improvement.

Furthermore, we found that even small numbers of critical incidents yielded potentially useful assessment data. The clearest example related to the Study Abroad Program. This was important supplemental information, given the relatively low CSEQ scores for gain in knowledge of other parts of the world (2.23, or “some” on a 4-point scale). On an administrative level, with-out the critical incidents, one would be left guessing as to how to address this issue. In our case, we discovered that the business college clearly would ben-efit from a greater promotion of study abroad.

Although we were pleased with the level of detail yielded by the critical incidents, we encountered some

unan-TABLE 4. Relationship of Critical Incidents to CSEQ Content: College of Business

Undergraduate Needs

Topic Good improvement Parallels to CSEQ results

Advising 12 6 Relations with administrative offices (2.86)a

CO-OP program 5 4 —

Curriculum

Course availability 2 7 —

Outside speakers 1 1 —

Diversity of course content 4 5 Gain, information relevant to a career 3.15

Field trips 2 1 —

Interrelationship of courses 0 1 —

Learned/used computer technology 1 3 Emphasis on information literacy skills (3.04) Study-abroad program 4 1 Gain, knowledge of other parts of the world 2.23

Teamwork 2 2 Gain, functioning as a team member 3.30

Textbooks 0 2 —

Other 0 1 —

Extracurricular activities 0 0 —

Professors

Adjuncts 0 1 —

Availability, caring, helpful 26 3 Relationships with faculty members (3.21) Knowledgeable, real-world oriented 14 3 Personal relevance, practical courses (2.82) Other

Business building 2 0 —

Interactions with the dean 2 2 —

Small class sizes 4 0 —

Student diversity 0 0 Student acquaintances scale (10 items) 2.43

Miscellaneous 0 3 —

Overall program 0 0 How well do you like the college? 3.27

aTo facilitate comparison across items, we converted items in brackets from 7-point to 4-point scales.

ticipated administrative issues associ-ated with their use. For example, a small number of the incidents were highly personal and derogatory, which potentially raises confidentiality con-cerns. Another practical issue was the time required to read and categorize the critical incidents, even with the rel-atively small sample involved in this study. Thus, large institutions likely would need to employ a sampling strategy to make the use of critical incidents tenable. Of course, the capa-bility to collect data efficiently from large numbers of students is a strength of standardized assessments such as the CSEQ.

Critical Incidents and CSEQ Correspondence

At first glance, some might be both-ered by the relative lack of convergence between the critical-incidents content and the CSEQ results, especially those pertaining to the university as a whole. Perhaps the content validity of the CSEQ could be enhanced by adding

items concerning course availability, career services, the registration process, and the hours that university services are available. Alternatively, institutions could take advantage of the CSEQ option of adding custom items. Never-theless, responses to those findings that focus on the addition of CSEQ items miss the more fundamental issue of response format differences (Schwartz, 1999). For example, CSEQ responses to items related to the quality of relation-ships with administrative offices or fac-ulty members cannot provide the same perspective as positive and negative incidents that name faculty and staff members individually. In some sense, the assessments are simply different, with each offering a relevant piece of the overall picture.

Generalizability of the Findings

Any determinations concerning the relationship of critical-incidents assess-ment to the CSEQ obviously must be made cautiously, because of the relative-ly small sample sizes in this study. For

example, one might wonder to what degree the critical-incident content is stable from year to year. Analysis of subsequent critical incidents revealed that the overall content framework pre-sented in Tables 2 and 3 was virtually unchanged at a later, more recent period. Moreover, the strong points have remained the same.

Future Research

Beyond generalizability issues, future researchers should address the effects of cueing in outcomes assessment. A format issue relates to our use of a negative inci-dent as an example to aid the stuinci-dents in understanding the kind of responses requested. This leaves open a question as to what impact a positive incident might have had on the responses.

Another interesting possibility for research has arisen from the recent AACSB effort to develop standardized surveys targeted to business programs per se (Detrick, 1999). Obviously, it would be of interest to examine the level of convergence obtained between

TABLE 5. Relationship of Critical Incidents to CSEQ Content: University

Undergraduate Needs

Topic Good improvement Parallels to CSEQ results

Advising 12 6 Relations with administrative offices (2.86)a

Advising (adult students) 1 1 —

Bookstore 0 0 —

Bursar 0 0 —

Career services 0 9 —

Campus police 2 2 —

Clubs 2 0 Used club organizations (5 items) 1.94

Computer lab 2 5 Used computer info tech (9 items) 2.56

Food services 0 2 —

Library 0 2 Used library (8 items) 2.18

Math/writing lab 1 0 Used a campus learning lab 1.69

Parking 1 10 —

Physical environment 2 0 —

Professors (nonbusiness) 1 4 —

Registration 0 4 —

Sports center 0 2 Used campus recreational facilities 2.42

Student commuter issues 1 1 —

Student housing 0 2 —

Textbooks 0 2 —

Tuition 0 1 —

Core curriculum 7 3 Gain, broad, general education 3.27

Miscellaneous 1 3 —

aTo facilitate comparison across items, we converted items in brackets from 7-point to 4-point scales.

business college critical incidents and AACSB data. However, we should note that the AACSB item content is compa-rable to the CSEQ in terms of its level of generality. Moreover, factors such as cost and student willingness to respond also will affect the choices that individ-ual institutions ultimately make.

REFERENCES

AACSB. (2001). Standards for business accredi-tation. St. Louis, MO: Author.

Allen, J. S., & Bycio, P. (1997). An evaluation of

the educational testing service major field achievement test in business. Journal of Accounting Education,15,503–514.

Bownas, D. A., & Bernardin, H. J. (1988). Criti-cal incident technique. In S. Gael (Ed.),The job analysis handbook for business, industry and government(pp. 1120–1137). New York: Wiley.

DeMong, R. F., Lindgren, J. H., & Perry, S. E. (1994). Designing an assessment program for accounting. Issues in Accounting Education,9, 11–27.

Detrick, G. (1999, February 28–March 2). AACSB/EBI assessment and continuous improvement tools. Outcome assessment: From strategy to program improvement. Clearwater Beach, FL.

Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident tech-nique. Psychological Bulletin,51, 327–358. Hoyt, W. T. (2000). Rater bias in psychological

research: When is it a problem and what can we do about it? Psychological Methods,5, 64–86. Pace, C. R., & Kuh, G. D. (1998). College student

experiences questionnaire(4th ed). Bloomington, IN: Center for Postsecondary Research and Plan-ning, Indiana University School of Education. Schuman, H., & Presser, S. (1981). Questions and

answers in attitude surveys. New York: Acade-mic Press.

Schwarz, N. (1999). Self-reports: How the ques-tions shape the answers. American Psycholo-gist,54,93–105.

Seldin, P. (1997). Improving college teaching. Bolton, MA: Anker.