Journal of Multinational Financial Management 10 (2000) 29 – 62

Domestic and international practice of deposit

insurance: a survey

Wai Sing Lee

a,1, Chuck C.Y. Kwok

b,*

aDepartment of Business Studies,The Hong Kong Polytechnic Uni6ersity,Hung Hom, Kowloon,Hong Kong

bDarla Moore School of Business,Uni

6ersity of South Carolina,Columbia,SC29208,USA

Received 3 July 1998; accepted 11 January 1999

Abstract

The literature on deposit insurance tends to be mostly confined to a discussion of the reform proposals and risk-related premium assessment methodologies. The theoretical expla-nation of the alternatives to the major components of a deposit insurance scheme is sketchy. Comparisons on the international practice of deposit insurance are not extensive and comprehensive enough. To fill the gaps in the literature, this paper examines the theoretical foundations of the key issues of a deposit insurance scheme, provides a critical comparison on the international practice of deposit insurance, and makes suggestions on how a complete deposit insurance scheme can be properly designed and implemented. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Banking; Deposit insurance; Deposit protection

JEL classification:G10; G21; G28

www.elsevier.com/locate/econbase

1. Introduction

The usual devices used by a country to prevent banking instability include bank regulation and supervision, the provision of last resort lending, and the

establish-ment of a deposit insurance (DI) or deposit protection scheme (DPS)2

. These three

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-803-777-3606; fax:+1-803-777-3609.

E-mail addresses:[email protected] (W.S. Lee), [email protected] (C.C.Y. Kwok) 1Tel.: +852-2766-7132; fax:+852-2765-0611.

2Deposit insurance is also known as ‘deposit guarantee’ or ‘deposit protection’.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 30

mechanisms are complementary to each other and are collectively known as the safety net in a banking system.

Although the concept of deposit insurance is quite simple, deposit insurance systems are relatively complex mechanisms. When designing a deposit insurance system, one has to grapple with a sizable number of complicated issues, some of which are not easy to resolve. The special banking environment (of the country proposing to set up a DPS) has to be taken into account at the design stage. Evidence from countries with deposit insurance shows that no DPS can be perfect. Most of the existing literature on deposit insurance tends to be overly confined to a discussion of the reform proposals and risk-related premium assessment method-ologies. The theoretical explanation of the alternatives to the major components of a deposit insurance scheme is sketchy. Comparisons on the international practice of deposit insurance are not extensive and comprehensive enough. Furthermore, advice on the design of a complete deposit insurance scheme is literally absent. To fill the gap in the literature, this paper examines the theoretical foundations of the key issues of a deposit insurance scheme, provides a critical comparison on the international practice of deposit, and makes suggestions on how a complete deposit insurance scheme can be designed and implemented properly.

In this article, we will first state the unique role of deposit insurance. This is followed by a detailed discussion of each of the alternatives of the major features of a DPS including administration, coverage, protection ceiling, financing, premium assessment and contingency measures. Reference will be made to international practice wherever possible. A summary of recommendations regarding the design of a DPS will be given at the end.

2. Rationale for deposit insurance

According to Fama (1980), banking is different from other types of business. Diamond (1984) has developed a theory of financial intermediation to show that banks are unique as they enhance social welfare by funding illiquid assets with very liquid liabilities. Diamond and Dybvig (1983) have further shown that the liquidity transformation that enables banks to provide useful services is also a source of their susceptibility to disruptive deposit runs. Friedman (1962) has convincingly re-marked that a fractional reserve banking industry is ‘inherently unstable’ in the sense that no bank, however soundly managed, can withstand a sustained run without governmental intervention or an organized rescue operation by other banks. Bank runs are contagious and the most pernicious effect of a panic is that it may result in the closing down of sound financial institutions along with the unsound. In light of the vulnerability of banks, deposit insurance has a vital role to play.

prevent-W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 31

ing runs on depository institutions. Finally, deposit insurance promotes fair compe-tition in the banking industry. On the other hand, there are arguments against a DPS for the reasons that they are expensive, unnecessary, ineffective or impractical in some countries. If a DPS is properly designed, most of the undesirable effects will be greatly minimized if not completely eliminated. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that there is almost unanimous advocacy for deposit insurance in developing countries by the IMF, the World Bank and other such policy advisors (McKinnon, 1991).

Most advanced (as well as some developing) countries have created a DPS of one form or another. Currently, we are aware of 51 countries that have set up their DPSs. Another 20 countries either intend to have or are making preparations for a

DPS. Out of these countries, four have drafted their DPSs3

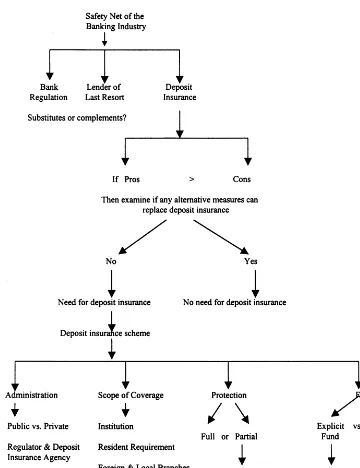

. In the next few sections, we shall discuss the components of a DPS in detail. For easy of reference, these major components are summarized in the bottom half of Fig. 1.

3. The administration of deposit insurance

3.1. Public 6s pri6ate schemes

Some academics advocate private sector solutions for deposit insurance. Their main argument is that private providers of insurance will encourage efficiency and effectiveness by removing institutions from the tangles of government bureaucracy.

England (1985)4 and Ely (1986) list the following advantages of a private deposit

insurance system:

1. a private insurer is more selective in choosing the insured;

2. a private insurer is not subject to political pressure and can therefore view each bank as a separate entity;

3. a private system is more flexible in monitoring and controlling risks undertaken by individual institutions;

4. a private insurer can move quickly to limit an insured institution’s incentive to take excessive risk; and

5. any private insurer who systematically under- or over-values the assets of an insured institution would soon be out of business.

Despite the above theoretical merits of private deposit insurance, the evidence supporting the superiority of private deposit insurance is not overwhelming. Unlike a public scheme, a private deposit insurance system can eliminate many potential

3As reported in the survey by the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (1993) and Fry et al. (1996), the countries that intend to set up deposit insurance schemes are: the Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Botswana, Bulgaria, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Lithuania, Malta, the Netherlands, Antilles, Pakistan, Portugal, Russia, and Sierra Leone. The countries that have already drafted deposit insurance are: Cyprus, Egypt, Jordan and Surinam. As reported in Foo (1998), China is preparing its DPS for medium- and small-sized banks.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 32

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 33

distortions. However, it faces many significant obstacles such as the problem of insurability, necessity of regulatory authority over insured members, lack of cred-itability, lack of risk measurement information to measure risk, possibility of higher premiums, diversification problems, and adverse selection. The main drawback is whether it can generate enough public confidence concerning the safety of their deposits. Diamond and Dybvig (1983), for instance, support public deposit in-surance on the grounds that ‘‘… the government may have a natural advantage in providing deposit insurance because private companies that have no power to tax would have to hold reserves in order to make their promises credible’’ (p. 416). Some scholars have demonstrated that deposit insurance cannot be provided successfully by the private sector. For example, Chan et al. (1992) (p. 243) concludes that ‘‘Subsidies are also shown to be necessary to cope with the moral

hazard5

associated with deposit insurance. Thus, fairly priced deposit insurance and by implication, competitive private-sector deposit insurance is impossible in a competitive banking system in which private information and moral hazard distort equilibrium.’’ Therefore, sufficient government involvement is needed to inspire the necessary public confidence. However, private deposit insurance schemes are nor-mally run under the control of the government. Thus the distinction between private and public is not as fundamental as it first appears.

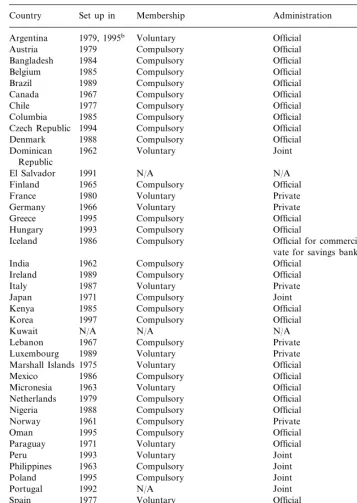

Information regarding the administration of deposit insurance schemes in differ-ent countries is summarized in Table 1. There are now 34 countries with public deposit insurance systems. Private deposit insurance systems are available in only seven countries. Iceland, Japan and five other countries have joint schemes. Information is not currently available for the remaining four countries.

3.2. Relationship between regulator and deposit insurance agency

Even if a DPS is public, it can be run as a separate unit of government administration or incorporated by the regulator of depository institutions. Good-hart (1988) strongly favors the combined functions of deposit insurance, supervi-sion and regulation undertaken by public-sector bodies.

There are several advantages to deposit insurance being organized and

adminis-tered by a regulatory authority. First, this would avoid any unnecessary and/or

undesirable duplication of facilities, particularly in the supervision and regulation of banks. Second, a deposit insurance scheme run by the government enjoys economies of scale in its fund investments. Third, a regulatory authority has both accumulated experience and valuable information on depository institutions. Such information is particularly useful for deciding on appropriate remedial action against troubled banks. Fourth, a deposit insurance fund run by the government has credibility with depositors. Fifth, a public deposit insurance system would eliminate another layer of bureaucracy, thus resulting in lower cost. This is especially important for a small economy.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 34

Table 1

Administration of deposit insurance schemesa

Administration Membership

Set up in Country

1979, 1995b Voluntary Official Argentina

1986 Official for commercial banks;

pri-Iceland

Trinidad and 1986 Compulsory Official

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 35

Table 1 (Continued)

Administration Country Set up in Membership

Official

Turkey 1983 Compulsory

Uganda 1995 Compulsory Official

UK 1982 Compulsory Official

US 1933 Compulsory for federal and state Official banks, varies by state

Venezuela 1985 Compulsory Joint

Yugoslavia 1985 N/A N/A

aSources: Abdulrahman (1995); Andre and Axel (1995) (pp. 18–20); Banker (1991) (p. 19); Bruyneel and Miller (1995); Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (1993); Carisano (1992); Economist (1990, 1995); Fry et al. (1996); Hong Kong Government (1992); Ko (1997); Kyei (1995); Fredbert (1995) (pp. 60–61); McCarthy (1980); Norwegian Banking Law Commission (1995); OECD (1995); Pennacchi (1987) (pp. 269–277); and Tally and Mas (1990, 1992).

bIn Argentina, explicit deposit protection was eliminated in 1991 and replaced with improved supervision and higher transparency. Explicit deposit guarantee was reintroduced in 1995.

In contrast, Kane (1985) emphasizes that regulators have their own objectives and therefore cannot be presumed to always have the best interests of the deposit insurance in mind.

There is no definite rule on whether the regulator and deposit insurer should be separate or combined in function. Garcia (1996) advises that one should take into consideration the history, institutional tradition, size and resources of the country. According to a survey conducted by the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (1993) on 20 DPSs, a separation of the two roles is found in 15 countries. Only Ireland, the Philippines and the US have combined the roles of the regulator and deposit insurance into one authority.

3.3. Compulsory 6s6oluntary membership

Assuming that a deposit insurance system is publicly run, should membership be voluntary or compulsory? To Baltensperger and Dermine (1986), voluntary in-surance may be enough if the only objective of a DPS is to offer bank customers the opportunity of holding a risk-free deposit.

There are strong arguments for compulsory membership, even though this involves greater government intrusion into the private sector. With a compulsory deposit insurance scheme, all depositors have a designated amount of protection. Compulsory deposit insurance is certainly in the best interest of the public. If the avoidance of bank runs and system crises is regarded as the main goal of deposit insurance, the scheme should be compulsory.

Voluntary deposit insurance allows each depositor to choose the amount of insurance coverage, but it may reduce aggregate social welfare if there is insufficient deposit insurance. A voluntary deposit insurance scheme would be exposed to the

problem of adverse selection6 in the sense that risk-prone banks are more likely to

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 36

join than those that are better managed. A voluntary system may fail to attract a sufficient number of members to accomplish its objectives. Also, large banks may be able to opt out of the system and avoid the cost of the premiums without markedly affecting depositors’ willingness to place funds with them. In countries with an uneven distribution of deposits, the cost of the scheme may become prohibitive for small banks without the full participation of large banks. Further-more, a voluntary deposit insurance scheme is likely to produce periodic large-scale transfers of deposits within the banking system — from insured to uninsured banks during good times and from uninsured to insured banks when individual banks are in trouble.

Unless a deposit insurance system is private7

, most of the current systems in force make membership compulsory. From Table 1, we can see that out of 51 countries’ deposit insurance schemes, membership is compulsory in 34 countries (e.g. Canada, Ireland, Japan, Sweden, the UK, and the US). Membership is optional in 13 countries, of which five (France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and Switzerland) have private systems. Membership of a DPS can also be based on type of depository institution. For example, in the US and Iceland, deposit protection schemes are compulsory for member banks and commercial banks, but are optional for private banks and other depository institutions. Details on membership of the remaining four systems are not currently available.

4. Scope of coverage

4.1. Institutions to be co6ered

One has to decide whether a deposit insurance scheme should cover all deposi-tory institutions or only some of them. Separate deposit insurance funds for banks and non-bank depository institutions have been created in the US, Iceland, Ireland, Finland, and Norway.

To arrive at a decision, one has to take into account several factors such as size of the economy, maximum deposit protection (as some countries have statutory minimum deposit constraints on some depository institutions), number and risk characteristics of the depository institutions concerned, their exposure to failure, cross subsidization, effect on the structure of the banking system, and the intended primary objective of the deposit insurance scheme. For a small economy which has the protection of small depositors as the deposit insurance objective, a single scheme may be adequate.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 37

4.2. Residential requirement

Should protection be provided only to local residents or extended to non-resident depositors? The exclusion of non-resident depositors is open to criticism since the possibility of a run by the uninsured still exists. The exclusion of non-residents from the DPS would incur additional administrative work and expenses, as banks do not typically distinguish accounts according to the residence of their customers.

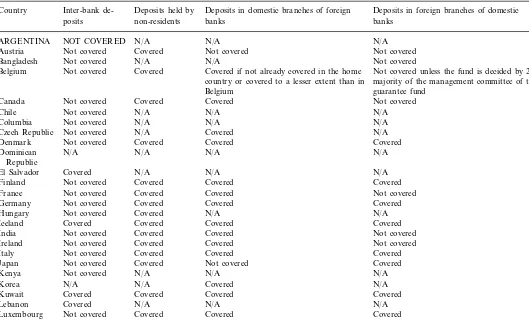

This issue is straightforward. As shown in Table 2, 31 schemes do not have any residency restrictions. Information is not available for the remaining 20 countries. That is to say, deposit insurance, once provided, is available to all depositors irrespective of their residency status (provided, of course, that such deposits meet all other necessary requirements for protection).

4.3. Protection of deposits at foreign and domestic banks

Another issue related to the scope of coverage is whether or not a DPS should protect deposits in domestic branches of foreign banks. If such deposits are covered, the local DPS would be exposed to external threat from foreign countries. As banks in countries with open financial markets are unavoidably subject to the same external risk, it may not be justifiable to exclude from protection deposits with foreign branches in the domestic country.

The practice of branch coverage is also presented in Table 2. Twenty-six countries including the US, the UK, Sweden, Italy, Germany, France and Canada extend protection to deposits in domestic branches of foreign banks. Such deposits should be covered as they are part of the banking system. A DPS would not be fully effective if deposits with foreign banks located in the home country were not protected.

To the best of our knowledge, deposits in foreign branches of domestic banks are not protected in 18 countries. Only 12 countries, including Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Mexico and Norway, extend protection to deposits in foreign branches of domestic banks.

4.4. Currency of deposits to be protected

Whether or not deposit insurance should be expanded to cover all domestic and foreign currency deposits is controversial. This issue was raised in a 1995 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) notice. It is sometimes argued that a deposit insurance system is not intended to protect, and therefore, should not protect foreign currency deposits, as they are more investment-oriented. Depositors who hold such accounts are deemed to be more willing to take risks.

W

Country Inter-bank de- Deposits held by Deposits in domestic branches of foreign Deposits in foreign branches of domestic banks

Austria Not covered Covered Not covered Not covered

Not covered N/A N/A Not covered

Bangladesh

Belgium Not covered Covered Covered if not already covered in the home Not covered unless the fund is decided by 2/3 majority of the management committee of the country or covered to a lesser extent than in

Belgium guarantee fund

Czech Republic Not covered Covered

Denmark Not covered Covered Covered Covered

N/A Finland Not covered Covered Covered

Not covered Covered Covered Not covered

France

Not covered Covered Covered Covered

Germany

India Not covered Covered Covered Not covered

Not covered Covered Covered Not covered

Ireland

Not covered Covered Covered Covered

Italy

Not covered Covered Covered Covered

W

Country Inter-bank de- Deposits held by Deposits in domestic branches of foreign Deposits in foreign branches of domestic banks

Not covered Covered Covered Covered

Norway

N/A

Peru Covered N/A N/A

Not covered Philippines Not covered Covered Covered

N/A

Sweden Covered Covered Not covered except in EEC countries

Not covered Covered Covered Not covered

Switzerland

N/A Taiwan Not covered Covered Covered

Not covered N/A N/A Not covered

Covered Covered Covered Not covered

US

N/A Venezuela Implicit covered N/A N/A

N/A

Yugoslavia N/A Covered N/A

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 40

21) argue that ‘‘…if foreign deposits were assessed, US banks would bear the cost directly. This would force these banks out of major wholesale markets abroad, with adverse effects on them and on the US’s role in the international economy’’. Nasser (1989) shares this view and reports that assessing premiums on foreign currency deposits may induce substantial cost and therefore jeopardize the competitive

positions of large US banks vis-a`-vis their foreign competitors8. He therefore

concludes that, with the internationalization of the banking business in the last several decades, this issue has become one of the more controversial topics dividing

bankers9. This remark is perhaps of special significance to those countries with

international financial centers. Another risk that arises from not protecting foreign currency deposits is the limited and partial protection to depositors, and conse-quently the threat to banking stability.

To arrive at a proper decision, a country should take into account the deposit structure, the primary objectives of a DPS, and interest differential between domestic and foreign currency deposits. If the majority of deposits in a country are in foreign currencies and the primary objective of a DPS is to prevent general bank runs, then there is a strong argument for protecting foreign currency deposits. For those countries with high interest differentials between local and foreign currency deposits, the need to protect foreign currency deposits is less strong, as the foreign currency deposits are more investment-oriented.

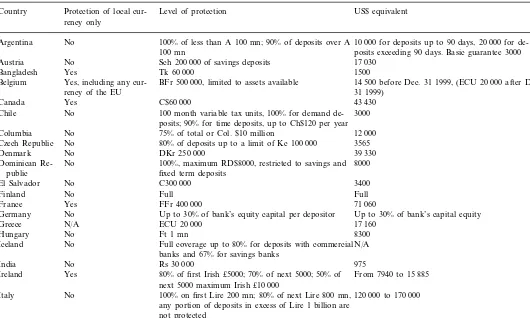

Table 3 shows that currently, 14 countries confine protection to deposits in their local currencies only. Thirty one countries protect both domestic and foreign currency deposits. Information is not currently available for the remaining six countries.

5. Level of protection

5.1. Full 6s partial protection

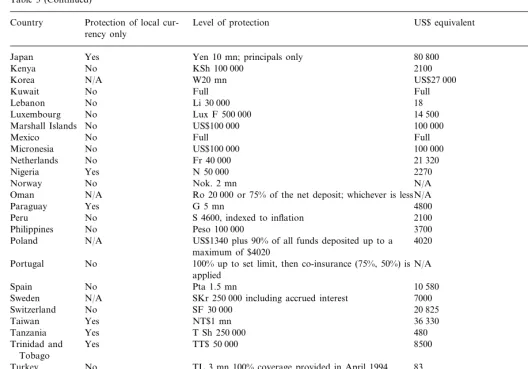

To gain the full benefit of a deposit insurance scheme, the extent of protection to depositors should be to achieve its objectives without inducing significant moral hazard. Fig. 2 presents the interrelated issues and problems connected with the decision on the extent of protection.

To Fry et al. (1996), full protection, or the American approach, is urged on the grounds of greater efficiency and equity. Another merit of full coverage is that it lowers the depositor’s incentive to withdraw funds from financially troubled banks and permits a bank to weather storms more successfully. It also enables the authorities to handle cases with greater ease. If the primary goal of deposit

8This is also the reason why the US Congress deliberately excluded deposits at foreign branches from the deposit insurance assessment base. See Huertas and Strauber (1986).

W

Argentina No 100% of less than A 100 mn; 90% of deposits over A 10 000 for deposits up to 90 days, 20 000 for de-posits exceeding 90 days. Basic guarantee 3000 100 mn

No Sch 200 000 of savings deposits 17 030

Austria

Yes Tk 60 000 1500

Bangladesh

BFr 500 000, limited to assets available

Belgium Yes, including any cur- 14 500 before Dec. 31 1999, (ECU 20 000 after Dec.

rency of the EU 31 1999)

Yes C$60 000 43 430

Canada

3000 100 month variable tax units, 100% for demand de-No

Chile

posits; 90% for time deposits, up to Ch$120 per year No

Columbia 75% of total or Col. $10 million 12 000

3565 80% of deposits up to a limit of Kc 100 000

Czech Republic No

No DKr 250 000 39 330

Denmark

100%, maximum RD$8000, restricted to savings and 8000 Dominican Re- No

Germany No Up to 30% of bank’s equity capital per depositor Up to 30% of bank’s capital equity ECU 20 000

N/A 17 160

Greece

No Ft 1 mn 8300

Hungary

Full coverage up to 80% for deposits with commercial N/A

Iceland No

banks and 67% for savings banks

No Rs 30 000 975

India

From 7940 to 15 885 80% of first Irish £5000; 70% of next 5000; 50% of

Yes Ireland

next 5000 maximum Irish £10 000

No 100% on first Lire 200 mn; 80% of next Lire 800 mn,120 000 to 170 000 Italy

W

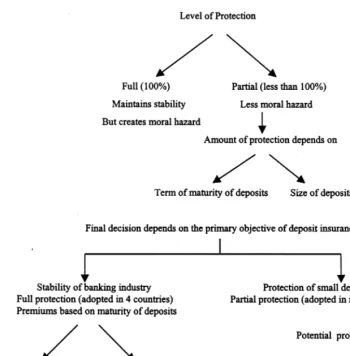

Protection of local cur- Level of protection

Country US$ equivalent

rency only

80 800 Yes

Japan Yen 10 mn; principals only

Kenya No KSh 100 000 2100

Korea N/A W20 mn US$27 000

Full

No Full

Kuwait

Lebanon No Li 30 000 18

No Lux F 500 000 14 500

Luxembourg

Marshall Islands No US$100 000 100 000

Full

No Full

Mexico

Micronesia No US$100 000 100 000

Netherlands No Fr 40 000 21 320

2270

No S 4600, indexed to inflation 2100

Peru

3700

Philippines No Peso 100 000

US$1340 plus 90% of all funds deposited up to a

N/A 4020

Poland

maximum of $4020

100% up to set limit, then co-insurance (75%, 50%) is

No N/A

N/A SKr 250 000 including accrued interest 7000 Sweden

Switzerland No SF 30 000 20 825

NT$1 mn

Yes 36 330

Taiwan

Tanzania Yes T Sh 250 000 480

Yes TT$ 50 000 8500

Trinidad and Tobago

83 TL 3 mn 100% coverage provided in April 1994

Turkey No

Yes USh 3 mn 3000

Uganda

Yes 75% of deposits up to £15 000 per depositor 24 638 UK

100 000 US$100 000

US No

Venezuela Yes Bs 4 mn 23 600

Yugoslavia No Full Full

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 43

Fig. 2. Determination of the level of protection.

insurance is to protect small unsophisticated depositors, as many have suggested, the protection limit does not need to be full. Full protection is preferred from a stability point of view, as it is especially effective in preventing over-reaction to groundless rumors by smaller unsophisticated depositors. Full protection can also reduce depositors’ needs to monitor behavior of their banks.

It can be counter-argued that even with full coverage of deposits, depositors still have every incentive to remove deposits from a failing bank due to the inconve-nience and temporary liquidity problem associated with having deposits blocked and having to wait for repayment. Therefore, even full protection reduces, but does not eliminate, the motivation for a run on a bank.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 44

is against the objective of stability in the banking system, which is one of the major reasons for deposit insurance.

The major rationale behind the proposal for not providing full deposit protection is to reduce the extent of moral hazard on the part of both depositor and depository institution. Therefore, Hoskins (1990) advises that ‘‘to truly reap the benefits of deposit insurance reform in the US, the current statutory limit (US$100 000) should be reduced, and co-insurance should be made available for coverage on balances that exceed the limit’’. To us, the high and comprehensive protection of the US deposit insurance scheme may be the root cause of the current

problems in that country’s deposit insurance10

.

Baer and Brewer (1986) support their view that uninsured depositors are an important source of market discipline with empirical evidence from the certificates-of-deposit market. In a co-insurance system, a price will be attributed to the risk of bank borrowing by the interest rates prevailing in the market.

It is questionable whether market discipline from the depositors who are partially protected is reliable. It should be noted, however, that the difficulty to judge the financial condition of intermediaries, coupled with low level of financial sophistica-tion of the typical depositor, may make market discipline by depositors an unfair and inefficient way to ensure prudent investments by financial institutions.

Ely (1986) points out an important fact that depositor monitoring is not reliable, as depositors are creditors and they have no upside disciplinary incentive, such as the opportunity for higher interest rates or principal appreciation. Instead, they run at the first sign of bank trouble. Furthermore, those who consistently and aggres-sively monitor their depository institutions are the first to run. To test whether market discipline anticipates banks’ downgrade to problem bank status, Simons and Cross (1991) employ residual analysis. Again, their results cast doubt on the supposed advantages that investors, and especially uninsured depositors, would have over bank regulators in restraining risk-taking by banks and in monitoring their management. Therefore, market discipline associated with co-insurance may not necessarily lessen the need for regulation.

On the decision of whether to provide full or partial protection, one has to take into account several considerations. First, if the primary objective of a DPS is to prevent system-wide bank runs, then protection should preferably be full. As Baltensperger and Dermine (1986) remark, the ‘small deposit’ criterion can be questioned if the objective is to protect the less-wealthy depositor. Income or wealth criteria may be more appropriate as the basis for premium assessment. Second, partial protection reduces the moral hazard impact, but the existence of effective explicit and implicit mechanisms within the banking system can help minimize the moral hazard problem even if protection is close to full. Third, ready availability and greater efficiency of the lender of last resort facilities and regulation and supervision place less reliance on a DPS as a means to prevent general banking

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 45

instability. In such a case, full deposit protection is less relevant. These two factors were highlighted by Tally and Mas (1992) as aspects that policymakers should

consider when weighing the pros and cons of alternative coverage arrangements11.

Fourth, full or partial protection, with the resulting amount of premiums charged, has an implication on the burden to the deposit insurance fund and the bearing of costs to the depository institutions or depositors. Fifth, the extent of protection to depositors depends on the extent of market discipline desired. Sixth, the availability of other channels of safe investment to small depositors may lessen the need to protect naive small depositors through a DPS. Finally, the protective ceiling also depends on the reliability of market discipline from the uninsured depositors and other bank creditors.

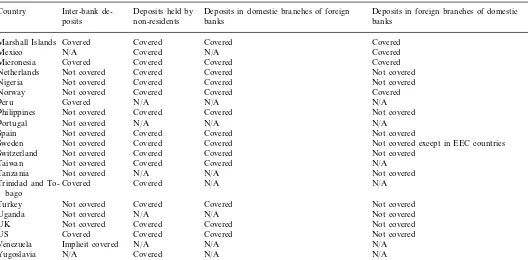

Table 3 shows the protective ceilings in 51 countries. Currently, only four countries, Finland, Kuwait, Mexico, and the former Yugoslavia, provide unlimited or full deposit insurance protection.

5.2. Rationale for protection ceiling

As full insurance undermines market discipline, it is frequently argued that there should be a ceiling on deposit insurance. If protection is not full and market discipline from uninsured depositors is not always reliable, what should be the cut-off line and how can we determine the percentage of maximum protection? Several proposals have been put forward to answer these questions.

From Fig. 2, we can see that if the main objective of deposit insurance is to enhance the stability of the banking system, it is more appropriate to base insurance coverage mainly on terms of maturity, with short-term deposits receiving insurance coverage. Regarding the definition of short-term deposits, Furlong (1984) advises that the deposit maturity chosen should allow an adequate period of time for evaluating the financial condition of banks.

Both Benston (1983) and Furlong (1984) recommend that all liquid deposits should be insured while those relatively illiquid ones should remain at risk. Kane (1986) also suggests that ‘‘authorities should investigate the effects of relating progressive declines in coverage directly to account size or interest rates and inversely to an account’s maturity’’ (p. 184). It is hoped that in this way the uninsured depositors will not have the incentive to withdraw their assets. The rationale for this proposal is that short-term or demand deposits typically constitute the major source of a bank run. This recommendation has several merits. It is obviously consistent with the classic deposit insurance objective of avoiding the cost of a bank run while encouraging banks to take fewer risks. Since the mismatch of asset and liability duration is a source of banking instability, linking deposit protection to deposit maturity may encourage depositor discipline on a bank’s risk-taking attitude.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 46

However, Carns (1989) states several problems connected with the adoption of a maturity-based insurance scheme. First, he points out the lack of a proper defini-tion of short-term maturity deposits. The sensitivity to bank runs varies even for deposits of the same maturity. Second, short-term deposits are usually of smaller amount as they carry lower interest rates. Third, to ensure that short-term depositors do not withdraw their deposits early, the penalty for doing so must be sufficiently high. The final, and indeed the most important problem, is caused by possible maturity switching over time. This would render the whole scheme ineffective and result in undesirable resource allocation in the economy. Carns (1989) accordingly warns that there may be some intervention in the financial market as a result of the change in the deposit structure due to the switching of deposits. Moreover, no concrete evidence supports the view that runs are often initiated by withdrawals of demand deposits.

According to the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (1993), current, savings and time deposits are covered by most deposit insurance schemes. Savings deposits are only protected in Switzerland and Turkey; wage accounts are also protected in Switzerland. In Chile, demand deposits are fully protected while savings deposits are protected up to 90%. Unfortunately, further information on deposit insurance based on the maturity of deposits is not available for comparison.

Fig. 2 shows that a variation of the above approach is a legislatively mandated co-insurance provision, based on deposit size, as the one currently used in the UK. Such a mechanism was proposed as a market-based incentive to reform the deposit insurance system in Canada (Gordon, 1994). Under such a scheme, deposit balances are fully insured up to a maximum amount, with balances above this limit subject to a reduced level of coverage. Depositors of amounts exceeding the fully insured ceiling can ‘co-insure’ the excess deposits. Goodhart (1988) is in favor of

such a partial protection system12

. However, Hall (1988) warns that in the UK, the degree of risk the depositors are asked to assume (25%) is too high if banking stability is the prime objective of deposit insurance.

Several problems plague the implementation of co-insurance that is based on deposit size. There is the possibility of bank runs and their contagion effects as a result of withdrawals by large risk-averse depositors. Some of the uninsured depositors may simply withdraw their deposits rather than wait to get their accrued interest at the maturity of their deposits. The uninsured depositors may not be attracted by the higher interest rate offered by their banks because the cost of a potential loss may be too high in the event of a bank failure. This is complicated by the fact that many large depositors are also more knowledgeable and better informed about the credit-worthiness of their banks, and thus may withdraw their deposits at the very first sign of problems. Some of the uninsured deposits may be of short-term nature and that they can easily be withdrawn at the first sign of trouble.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 47

Effective implementation of co-insurance, no matter which format is adopted, is very difficult, if not impossible. Although coverage is applied on a per depositor per bank basis, loopholes to circumventing such rule exist. A depositor may hold accounts under different names within a single bank. If the objective of a DPS is to protect small depositors rather than prevent system-wide bank runs, inter-bank deposits should be excluded from protection coverage. From Table 2, we can see that this is practiced in 32 countries. Inter-bank deposits are only covered in nine countries including Kuwait, Peru, the US, Trinidad and Tobago.

5.3. Le6el of protection ceiling

If we are in favor of some kind of co-insurance or partial protection, our next task is the determination of the protection ceiling. This is necessary as we have to keep the costs of a DPS within affordable limits and at the same time ensure that the major benefits go to small depositors. Such objectives cannot be easily achieved, as we cannot assess the wealth of depositors merely on the basis of their deposits in a single bank, unless the protection is on a per depositor per bank basis. The ceiling that is too low increases the number of depositors at risk and, therefore, these depositors are more likely to exert market discipline on their banks. On the other hand, if the ceiling is too high, it enables more depositors to enjoy greater protection but with a greater degree of moral hazard. Therefore, Dreyfus et al. (1994) assert that the choice of a cap on insured deposits does not need to be trivial. Their study shows that a liability less than that calculated on an actuarial basis by the insurer will affect the probability that a bank will be optimally closed by the insurer. Dreyfus et al. (1994) warn that if the insured ceiling is set ‘too low’, a bank may be unable to pay the interest rate or risk premium required by uninsured depositors. As a result, the bank will have to be closed.

According to Walker (1994), the primary cause of the financial distress of US thrift institutions that failed in recent years appears to be the increase in the deposit insurance limit to US$100 000. Consequently the FDIC has considered the

possibil-ity of curtailing the scope of deposit protection to improve market discipline13.

However, some other countries are moving in the opposite direction. The EU has proposed to extend the scope of deposit protection within its member countries,

and has raised the limit on the coverage from 15 000 to 20 000 ECU14. Dale (1993)

contends that the idea of depositor protection and the simultaneous restriction of that protection are paradoxical.

Of course, any limit on the ceiling of protection would be irrelevant if depositors could make use of loopholes in the scheme by establishing separately insured deposits in the names of various household members. The opportunistic use of other means, such as partnerships and nominee companies, to obtain multiple coverage must be strictly forbidden.

13See Di Nuzzo (1991), p. 10.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 48

Table 3 shows the protection ceilings in 51 countries. Currently, only four countries, Finland, Kuwait, Mexico, and the former Yugoslavia, provided unlim-ited or full deposit insurance protection. As it is not always possible to protect all deposits, the scope of any deposit insurance should be limited in one way or another. However, several patterns can be grouped for discussion. First, for those countries with partial protection, the protection ceiling ranges from 50 to 90% on all deposits. Second, many countries (such as Italy, Argentina, Chile, Iceland, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the UK, Taiwan and the Netherlands) adopt a tiered approach and give full protection up to a certain limit, with excessive deposits subject to co-insurance. Thirty-six countries provide full protection for deposits below a certain amount, ranging from US$200 in Lebanon to US$170 000 in Italy. Any deposits exceeding the limit are at risk. Third, the extent of protection can be based on the type of deposit. In Chile, protection is full for demand deposits but savings deposits are protected only up to 90%. Informa-tion for the remaining four countries is not currently available.

Indeed, the only way to really accomplish the objective of deposit insurance is to restrict the maximum amount of protection available to one person from all depository institutions. With the extensive use of computers nowadays, such a rule can be implemented easily in many countries.

5.4. Incenti6e-compatible protection ceiling

In order to reduce the moral hazard and to encourage banks to provide information to the deposit insurance agency for premium assessment purposes, it has been proposed that deposit insurance should be voluntary. The incorporation of a certain element of voluntarism into the amount of deposit insurance has been proposed in the literature. A simple way is to provide banks with an option of securing additional protection for their depositors. Kane (1986) proposes the extension of the optional insurance to depositors themselves. A scheme which allows a depository institution to choose its preferred combination of capital requirements that are inversely related to deposit insurance premiums is suggested by Chan et al. (1992). Fan (1995) proposes a deposit insurance scheme which allows a depositor to choose either ‘full’ or ‘partial’ insurance from the deposit insurance fund. If a depositor chooses to be ‘fully’ insured, he will have to forgo some of the interest on his deposit in order to pay for the cost of deposit insurance. If a depositor buys ‘partial’ insurance, he earns the market interest rate from his deposit when his bank is sound, but he will be fined if his bank goes bankrupt or fails to meet specified criteria. In this proposal, a depositor can change his form of insurance at any time. The main defect of this proposal is that the incentive to earn the market rate may not be strong enough for a depositor to maintain his deposits when his bank runs into trouble.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 49

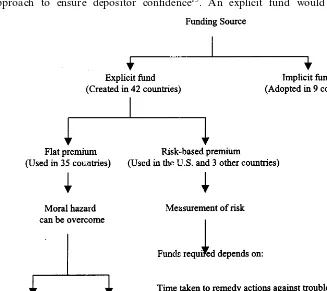

6. Funding of the deposit insurance scheme

There are two main funding arrangements. One is to set up a fund with regular contributions from insured banks out of which claims can be met. The other approach is unfunded, or with a relatively small initial fund, taking an ex post approach with premium assessments levied after bank failures. Fig. 3 shows the decisions that need to be made with regard to the financing of a deposit insurance fund. Some have argued that since a government may be responsible for the failure of a bank and yet also benefits from banking stability, it should bear part of the deposit insurance costs. Both types of funding arrangement have a moral hazard impact and Fry et al. (1996) have remarked that the conversion from implicit deposit protection to explicit deposit insurance would result in less moral hazard for banks but more moral hazard on the part of the depositors (pp. 366 – 367).

The creation of an explicit deposit insurance fund, with premiums collected from insured banks on the basis of their deposits, would seem to be the most sensible

approach to ensure depositor confidence15. An explicit fund would give more

Fig. 3. Funding arrangement.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 50

psychological comfort to depositors, and the financial burden of the DPS could be more evenly spread.

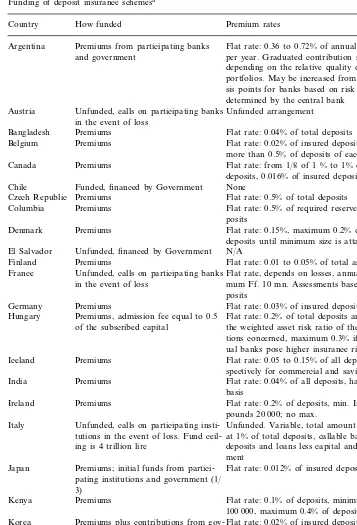

From Table 4, we can see that 49 countries have explicit deposit insurance funds with premiums collected from insured members. In the nine countries that do not maintain explicit funds, calls for premiums are made on insured banks only when necessary. In Chile, El Salvador and Kuwait, insurance funds are financed by the government. Tally and Mas (1992) report that in the former Yugoslavia, costs of the deposit insurance system are absorbed entirely by the government. In Argentina, Japan, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Taiwan, Trinidad and Tobago, and Uganda, the government contributes at least one-third of the funds.

6.1. Premium assessment

The most formidable technical problem in the design of a deposit insurance scheme is the determination of an appropriate premium structure. A properly structured premium system can be used to lessen moral hazard and reduce adverse selection effects. The acceptability of deposit insurance to the participating banks depends, to a great extent, on the design of the premium structure. The decision has great significance upon additional types of bank regulation required.

Fig. 3 shows the choice of premium structure between a flat rate for all banks and a variable rate related to the riskiness of each bank. A flat-rate premium system is easy to implement, but leaves much to be desired. A premium structure related to the risk of each insured bank is sound in theory, but difficult to implement.

The problem of how to assess premiums is complicated by the difficulty in calculating the amount of insurance funds necessary to meet the claims of deposi-tors. The loss to a deposit insurance fund depends on (1) the ceiling of protection; (2) the difference between the amount of insured deposits and the market (sale)

value of the failed bank’s assets; and (3)when a problem bank is detected, and how

fast the failing bank is closed, rather than on the riskiness of its portfolio. Horvitz (1983) has pointed out that the losses of a deposit insurance system are not closely related to the riskiness of insured institutions. Losses are for the most part, a function of when a failed bank or savings institution is closed. If a bank is immediately closed when its net worth is exhausted, then the premiums are only needed to cover the operational expenses of the deposit insurance agency.

6.2. Risk-related premiums

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 51

Table 4

Funding of deposit insurance schemesa

How funded Premium rates

Country

Premiums from participating banks Flat rate: 0.36 to 0.72% of annual deposits Argentina

and government per year. Graduated contribution structure depending on the relative quality of bank’s portfolios. May be increased from three ba-sis points for banks based on risk indicators determined by the central bank

Unfunded arrangement Austria Unfunded, calls on participating banks

in the event of loss

Premiums Flat rate: 0.04% of total deposits Bangladesh

Belgium Premiums Flat rate: 0.02% of insured deposits, not more than 0.5% of deposits of each bank Flat rate: from 1/8 of 1 % to 1% of insured Premiums

Canada

deposits, 0.016% of insured deposits Chile Funded, financed by Government None

Flat rate: 0.5% of total deposits Premiums

Czech Republic

Premiums

Columbia Flat rate: 0.5% of required reserves on de-posits

Flat rate: 0.15%, maximum 0.2% of total Premiums

Denmark

deposits until minimum size is attained El Salvador Unfunded, financed by Government N/A

Flat rate: 0.01 to 0.05% of total assets Premiums

Finland

France Unfunded, calls on participating banksFlat rate, depends on losses, annual maxi-mum Ff. 10 mn. Assessments based on de-in the event of loss

posits

Flat rate: 0.03% of insured deposits Premiums

Germany

Hungary Premiums, admission fee equal to 0.5 Flat rate: 0.2% of total deposits and from the weighted asset risk ratio of the institu-of the subscribed capital

tions concerned, maximum 0.3% if individ-ual banks pose higher insurance risk Flat rate: 0.05 to 0.15% of all deposits re-Premiums

Iceland

spectively for commercial and savings banks India Premiums Flat rate: 0.04% of all deposits, half yearly

basis

Flat rate: 0.2% of deposits, min. Irish Premiums

Ireland

pounds 20 000; no max.

Italy Unfunded, calls on participating insti- Unfunded. Variable, total amount fund set at 1% of total deposits, callable based on tutions in the event of loss. Fund

ceil-ing is 4 trillion lire deposits and loans less capital and reassess-ment

Japan Premiums; initial funds from partici- Flat rate: 0.012% of insured deposits pating institutions and government (1/

3) Premiums

Kenya Flat rate: 0.1% of deposits, minimum K Sh

100 000, maximum 0.4% of deposits Premiums plus contributions from gov- Flat rate: 0.02% of insured deposits, up to Korea

0.05% of insured deposits if risk-related ernment

Kuwait Funded, financed by Government None

Premiums Flat rate: between 0.02 and 0.05% of in-Lebanon

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 52

Table 4 (Continued)

How funded Premium rates

Country

Insured deposits of surviving institutions, Unfunded, calls on surviving

institu-Luxembourg

tions based on percentage of loss to be met Marshall Islands Premiums Variable, follows the US model

Premiums

Mexico Flat rate: 0.3% of insured deposits, regular monthly contributions

Premiums Variable, follows the US model Micronesia

Unfunded, calls on participating

insti-Netherlands Flat rate, annual contribution from individ-tutions in the event of loss ual institution not to exceed 10% of its core

capital Premiums

Nigeria Flat rate: 0.94 of 1% of all deposits

Norway Premiums and contribution from gov- Flat maximum rate: 0.015% of total assets; government contributes an equal amount ernment

Contributions from banks and

govern-Oman Flat rate: 0.01–0.03% of total deposits

ment on an equal basis

Premiums Flat rate: 0.25% of deposits Paraguay

Premiums Flat rate: 0.75% of total deposits, quarterly Peru

basis Premiums

Philippines Flat rate between 0.083 and 025% of total deposits, average 0.0667% of total deposits Poland Premiums Flat rate: 0.2% of deposits

Based on previous year’s average monthly Premiums, half from government

Portugal

deposits

Flat rate: 0.25% of deposits, 1/2 from gov-Contributions from banks and

govern-Spain

ment on an equal basis ernment

Sweden Premiums Flat rate: 0.25% of deposits, annual basic fees may be varied, based on each bank’s capital ratio and aggregate result of the guarantee system

Switzerland Unfunded, calls on participating insti- Flat and variable rates, depends on banks’ balances and total deposits

tutions in the event of loss

Flat rate: 0.015% of insured deposits Premiums and contributions from

gov-Taiwan

ernment

Banks and government Flat rate: 0.1% of deposits Tanzania

Premiums; government also partici- Flat rate: 0.2% of average deposits Trinidad and

To-bago pates in the financing

Premiums Flat rate: 0.3% of insured deposits Turkey

Flat rate: 0.2% of deposits Uganda Premiums; government provides some

funding

Premiums, initial contribution of Flat rate but progressive levy with max. of UK

0.3% of domestic sterling deposits £10 000, further calls when necessary

up to £300 000

US Contributions from participating insti- Between 0.195 and 0.23% of domestic de-posits (from 1990), risk-based since 1993, tutions

depends on individual bank rating, average 0.2435 for banks and 0.248% for thrifts in 1994

Venezuela Premiums Flat rate: 0.5% of total deposits every 6 months

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 53

application of some key variables such as credit risk, interest rate risk and liquidity risk, in order to assess the specific risk of each bank for premium assessment purposes. Clearly, such a list cannot be exhaustive. The appearance of new sources of risk as a result of financial innovation (e.g. derivatives) has made any attempt at the precise measurement of risk factors very difficult. Therefore, Goodman and Shaffer (1983) argue that a risk-related insurance premium system will generally fail to cope adequately with new, previously unanticipated, sources of risk. They say it is like ‘a dog chasing its own tail’. A similar view is held by Berger (1994).

The major problem of variable insurance premiums is the identification and measurement of risk characteristics of banks. For a variable premium structure to be successful, an extensive degree of information, continuous surveillance and supervision by regulators is required. This is a formidable task that requires advance knowledge of the precise risk-return schedules of all current on and off balance sheet activities. Thus far, researchers have not been able to identify any objective way of assessing insurance premiums. Horvitz (1983) and Kane (1986) warn that mispriced deposit insurance generates subsidies to stockholders, man-agers, and deposit brokers. They are the ones who are regarded as the true beneficiaries of deposit insurance. Several studies have also shown objections to the use of risk-sensitive premiums. For example, Goodman and Santomero (1986) advise that a variable-rate system raises the cost of funds to the real sector and increases the probability of bankruptcy for the borrowing firms. When such bankruptcies occur, society experiences a dead weight loss. Goldberg and Hariku-mar (1991) claim that in the absence of symmetric information between bank managers and the insurance agency, insurance premiums based on projected and actual risk levels do not control risk-taking incentive. They hold that the only way to control this incentive is to levy a relatively high premium, which is not fair in the actuarial sense. According to Chan et al.’s model (Chan et al., 1992), when banks hold non-traded private-information assets, no equilibrium price for deposit in-surance exists, unless banks earn rent or are subsidized. Furthermore, Crane (1995) notes that the fair pricing of deposit insurance eliminates inequitable wealth transfers, but does not necessarily lead to an efficient equilibrium.

Even if risk-based premiums could be objectively estimated and effectively implemented, we would still have to consider the problem that variable premiums may force weak institutions to seek even higher risk investments in order to absorb the higher premiums charged. It is unfortunate that a risk-based deposit premium structure does not automatically eliminate moral hazard.

The practice of risk-sensitive premiums is extremely limited and only the United States, Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Argentina (since 1995) relate their

in-surance premiums to the riskiness of each bank16. Ko (1997) reports that Korea

wishes to adopt a risk-related premium structure when such techniques are available.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 54

It is fair to say that assessment of premiums is the most problematic issue of

deposit insurance17. The complex nature of implementing a risk-sensitive deposit

premium system is summed up in the following quote from the FDIC (1983a)18:

The ‘ideal system’ with premiums tied closely to risk is simply not feasible. Such a system would require the FDIC to be given an extreme amount of authority. Moreover, it would entail unrealistic data requirements and much more advanced risk quantification techniques than are currently imaginable.

6.3. Flat premium rate structure

Because risk-related premiums are difficult to implement, a flat-rate premium schedule may be a possible alternative. A flat-rate premium structure is easy to understand and to implement. Indeed, a flat-rate deposit premium schedule can

meet many of the criteria of a good deposit insurance structure19.

As expected, criticisms of the flat-rate deposit insurance scheme are abundant. Among them are comments made by Buser et al. (1981), Benston et al. (1986), Goodman and Santomero (1986), Mussa (1986), Kane (1985, 1987), Duan et al. (1992), Wheelock (1992) and Shiers (1994). Most criticisms center on amplification of the moral hazard problem. Risk-seeking institutions are charged the same rate per insured dollar as conservative institutions. Thus, risk takers are not penalized for their aggressiveness. Many concede that the flat-rate premium structure in a sense, actually encourages risk-taking by insufficiently allocating the commensurate costs of risk. A related criticism is that sound banks, in essence, subsidize excessive risk-taking behavior of their competitors.

With flat-rate insurance premiums and the way that the FDIC in the US always supports large banks with all the means at its disposal, depositors enjoy greater protection at large banks than at small banks. Thus, Keeton (1990) concludes that a flat-rate insurance premium system can unfairly discriminate against small banks. Needless to say, a combination of flat-rate premium system and full protection significantly exacerbates the moral hazard problem. The former may lead to excessive risk-taking by depository institutions, and the latter reduces the incentive

17There has been a continuous stream of literature discussing the deposit insurance premium. Some examples of recently published studies are Hwang et al. (1997), Karels et al. (1997), and Hazlett (1997).

18Also quoted in Scott (1986), p. 94.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 55

for depositors to monitor the depository institutions in which they place their money.

Only the US, Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Argentina (since 1995) use a risk-sensitive premium system. Thirty-five countries use a flat-premium system with premium charged on deposits ranging from 0.0125% in Japan to 0.94% in Nigeria. Deposit insurance with a flat-rate premium alone may not cause bank failures. Some scholars offer other causes for an increasing number of bank failures in the US. For example, Schwartz (1987) states that the recent problems of the US banks are due more to inflation instability and the consequent interest rate instability, than to deposit insurance. Keeley (1990) attributes the recent increase in bank failures in the US to lower capital-asset ratios caused by declining bank charter values. This decline is triggered by increased competition faced by commercial banks. Other causes of bank failures include poor management, infrequent and lax bank examination. The Basle Capital Adequacy Ratio, implemented in 1993 in many countries, may lessen moral hazard on the part of depository institutions. If necessary, additional measures to restrict and penalize banks’ excessive risk-taking behavior may be imposed under a flat-rate deposit premium system.

Recently, scholars such as Nagaragan and Sealey (1995) (p. 1100) have argued that ‘‘even flat-rate deposit insurance can be optimal when combined with a sound forbearance policy and a minimum capital standard’’. The appropriateness of a flat-rate premium structure should be evaluated with reference to the existing regulatory framework of a country. Usually, implicit premium mechanisms within a regulatory system may reduce the moral hazard associated with deposit insurance. For example, potential financial losses of a bank may curtail the risk-taking incentive of bank management. Bank management may also exercise self-constraint in order to avoid the damage to their careers in case of bank failures.

6.4. Basis for premium assessment

Deposit insurance premiums can be assessed on either total deposits or insured deposits. Alternatively, assessments can be based on, for example, average monthly or quarterly deposit balances during a certain period, rather than on balances as of a given assessment date.

To prevent switching of insured deposits to uninsured deposits at the end of the year, premiums should be charged on total deposits. Switching deposits is a real possibility if insurance premiums are charged only on year-end insured deposits. Applying the same premium rate to all depositors is administratively simpler but involves cross-subsidization. Some may argue that charging premiums on total deposits instead of on insured deposits is not fair to depositors with deposits exceeding the protection limit. This is particularly unfair to large banks, as they

may have a greater number of large uninsured depositors20

. However, we should not ignore the fact that large banks, are less likely to fail because they can more

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 56

easily obtain financial support from the government. As referred to above, deposits with foreign banks located in the home country are usually not subject to insurance premiums, which puts the large banks on an equal footing with their smaller counterparts.

Table 4 shows that 28 countries assess their premiums on total deposits while 10 countries set their premiums only on insured deposits. In Norway and Finland, premiums are set on banks’ assets. In Korea, Sweden and Italy, premiums are directly or indirectly related to banks’ assets. Such an approach was acknowledged by the FDIC as a substantial departure from tradition without any direct

relation-ship between assessed items and those items insured21. Insurance premiums should

not be charged on bank assets, as only bank deposits are protected. Furthermore, liquidity and diversification of assets are more relevant than just absolute value of assets as a measurement of bank risk.

6.5. Contingency funding arrangement

The adequacy of the deposit insurance fund depends on four major cash flows, namely premium payments, investment income, claims payments, and administra-tive expenses. Of these, the insurance fund has some control over the premium payments and administrative expenses. Of course, the fund has no control at all over investment income and claims payments. Therefore, it is difficult to predict the amount of funds that would be sufficient to meet any claims made upon the deposit

insurance agency22,23.

According to a survey by the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (1993), there exists no formal mechanism to determine the size of deposit insurance funds. Only six countries out of a total of 20 countries responding to the survey, have a target fund size. Both the UK and Denmark have a minimum target fund size. In the other four countries, target fund size ranges from 0.5% of insured deposits in India to 1.5% of total assets in Norway. As Dale (1984) reports, the size of insurance funds, relative to the insured deposits, varies considerably among coun-tries (i.e. about 1% in the US and 0.067% in Japan). In councoun-tries outside North America, funds are maintained at a significantly lower level. Benston (1983) does

21ABA (1995), p. 10.

22According to Tally and Mas (1992), one way to structure financing of a deposit insurance system is to set a target range for the fund’s capital ratio (i.e. capital plus reserves to insured deposits), and then overtime, and maintain the fund’s actual capital ratio within that range. Besides capital injection, the size of the fund depends on four major cash flows.

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62 57

not regard insurance fund size as the key to maintenance of the public’s confidence in the deposit insurance system. ‘‘The fund itself is irrelevant, and the ultimate guarantor is the US Treasury, whose resources are inexhaustible’’ (p. 20). Bal-tensperger and Dermine (1986) (p. 78) also regard the size of the insurance fund as ‘‘…a rather meaningless number, … as the insurance fund must be seen in relation to potential payouts and the possibility of raising additional funds.’’

There is always a risk of a funds shortage particularly for a new scheme. Contingency funding measures for dealing with situations where the accumulated resources of the DPS are inadequate are an essential part of a DPS. Table 5 shows different measures adopted in different countries. First, the protection ceiling can be limited to the available resources of a DPS, even though it has guaranteed deposits up to a specified amount. This measure is adopted in Iceland and Ireland. Second, as in the case of Belgium, the level of coverage can be reduced if assets are inadequate to meet the claims. This adversely undermines public confidence and renders the DPS ineffective in preventing bank runs. The third measure, used in Italy, is to defer the payment of claims. This option is better than the first two, but the slow payment of claims runs contrary to the original objective of a DPS. The

uncertainty of when protection is available to depositors could reduce public

confidence in the DPS. The fourth measure is to make advance calls on insured banks in order to make additional premium contributions. This could create an uncertain financial burden on banks. Making advance premium calls on participat-ing banks is the primary measure of contparticipat-ingency fundparticipat-ing in France, Germany, Luxembourg, Oman and the UK. Last but not least, a DPS may be allowed to borrow either from the government or from the public. From the depositors’ point of view, government support would be ideal. Tally and Mas (1992) conclude that one of the basic requirements for the success of a DPS is that the government should exhibit a willingness to adequately fund a DPS and give it necessary backup

to get the system through a period of stress24. Government support is necessary

particularly during the transitional period when a fund has not yet accumulated sufficient resources. Experience suggests that government support is necessary to secure the confidence of depositors. Financial support from the government, as a contingency funding option, is adopted in 16 countries including Austria, Canada, Denmark, India, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, the Philippines, Spain, the UK and the US.

7. Summary and conclusions

In this review we have presented details with justifications, of the essential components of a deposit insurance scheme. We have also reviewed how these DPS components are practiced in different countries. The controversial nature of deposit insurance is clear from our discussion of the issues concerned. The paradox of

W.S.Lee,C.C.Y.Kwok/J.of Multi.Fin.Manag.10 (2000) 29 – 62

Argentina Advanced contributions from banks up to 1 year’s regular contributions, target amount of US$2 billion or 5% of total deposits whichever is higher Austria Government backed bonds may be issued

Belgium Can call for additional annual contribution up to 0.4% of deposits. Guar-antee from state, up to Bfr 3 billion for any institution, may proportion-ally reduce reimbursements

Borrowing from government up to C$6 billion, further borrowing subject Canada

to parliamentary approval

Borrowing from government and the central bank, premiums will be dou-Czech Republic

bled until the loans are repaid

Borrowing from banks with guarantee from government, minimum size Denmark

DKR 3 billion

France Extra calls up to FFr 1000 million can be made in regard to a 5-year period

Annual levy may be doubled Germany

Fund is recalculated annually Iceland

India May borrow from the central bank, government backing subject to parlia-mentary approval, healthy level estimated at 0.5% of insured deposits Ireland Fund may be reconstituted once per year

Defer payment or diminish the compensation to be paid Italy

Permitted to borrow up to Y500 billion from central bank, callable contri-Japan

butions may be increased up to an additional limit of 0.05% of total deposits

Borrowing up to a maximum of W500 billion Korea

Lebanon Borrowing from the central bank Additional contributions from participants Luxembourg

Netherlands Government backing

Loans from government, target fund size 1.5% of total assets Norway

Additional or special contributions Oman

Borrowing from the central bank and other banks Philippines

Government contribution may increase fourfold Spain

Sweden Annual fee may be varied based on the aggregate result of the guarantee system

Underwritten by member banks Switzerland

Long-term loans from the central bank Trinidad and Tobago

Funds from government Turkey

UK Government has authority to borrow £10 million. Government may raise the maximum percentage payable; £125 million advance facility from the Bank of England. Minimum and maximum size of fund are £5 and £6 million respectively

US Borrowing up to 3 billion from the Treasury, maintained reserves equal to 1.25% of insured deposits, up to 1.5% if necessary