www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

The influence of environmental change on the

behaviour of sheltered dogs

Deborah L. Wells

), Peter G. Hepper

Canine BehaÕiour Centre, School of Psychology, The Queen’s UniÕersity of Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN,

Northern Ireland, UK

Accepted 21 December 1999

Abstract

The majority of sheltered dogs are overlooked for purchase because they are considered undesirable by potential buyers. Many factors may determine a dog’s appeal, although of interest here are the dog’s behaviour and cage environment which can influence its desirability. People prefer dogs which are at the front rather than the back of the cage, quiet as opposed to barking, and alert rather than non-alert. Potential buyers also prefer dogs which are held in complex as opposed to barren environments. This study examined the behaviour of sheltered dogs in response to environmental change, to determine whether it influenced dog behaviour in ways that could be perceived as desirable to potential dog buyers, andror had any effect upon the incidence of dogs purchased from the shelter. One hundred and twenty dogs sheltered by the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals were studied over a 4-h period. The dogs’ position in the cage, vocalisation, and activity were investigated in response to increased human social stimulation, moving the dog’s bed to the front of the cage, or suspending a toy from the front of the dog’s cage. Social stimulation resulted in dogs spending more time at the front of the enclosure, more time standing, and slightly more time barking. Moving the bed to the front of the cage encouraged dogs to this position, but did not influence activity or vocalisation. Suspending a toy at the front of the pen exerted no effect on dog behaviour, although its presence in the pen may help to promote more positive perceptions of dog desirability. The incidence of dogs purchased from the rescue shelter increased whenever the dogs’ cages were fitted with a bed at the front of the pen, whenever the dogs were subjected to increased regular human contact, and whenever a toy was placed at the front of the enclosure. Findings highlight the important role that cage environment can play in

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q028-90-274386; fax:q028-90-66-4144.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] D.L. Wells .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

shaping the behaviour of sheltered dogs and influencing whether or not an animal will become purchased.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Behaviour; Captivity; Dogs; Rescue shelters; Welfare; Environment; Enrichment

1. Introduction

Rescue shelters provide temporary housing for thousands of stray and abandoned dogs every year. One of the main goals of most rescue shelters is to ensure that the dogs in their care find new homes. Many factors may influence whether or not a sheltered dog becomes purchased by a new owner, although of particular importance are the animal’s

Ž .

behaviour and, to a slightly lesser degree, its cage environment Wells, 1996 . Unfortu-nately, these are frequently considered undesirable by potential buyers, and many

Ž .

sheltered dogs are overlooked for purchase as a consequence Wells, 1996 . The following study examined the behaviour of sheltered dogs in response to three types of environmental change to determine whether they influenced dog behaviour in ways that could be perceived as desirable to potential dog buyers. The effect of manipulating the dogs’ cage environment on the incidence of dogs subsequently purchased from the shelter was also examined.

Recent years have witnessed an increasing concern for the welfare of dogs housed in rescue shelters and other captive conditions, e.g. laboratories. Much of this work has focused on ways of promoting the welfare of dogs whilst they are held in captivity by

Ž

improving their housing conditions see Hubrecht 1995a, Hubrecht and Turner, 1998, for

. Ž

reviews . Studies have explored the effects of cage size e.g., Hite et al., 1977; Hughes

. Ž

et al., 1989; Hetts et al., 1992; Hubrecht et al., 1992 , social contacts e.g., Hetts et al., 1992; Hubrecht, 1993; Hubrecht et al., 1992; Mertens and Unshelm, 1996; Wells and

. Ž

Hepper, 1998 , and the introduction of cage furniture andror toys Hetts et al., 1992; .

Hubrecht, 1993, 1995b; Wells, 1996; Wells and Hepper, 1992 on the behaviour and welfare of captive dogs. These studies indicate that dogs should ideally be housed in cages that allow for the fulfillment of the animal’s needs and promote both physical and psychological well-being.

Although there is obvious value to promoting the welfare of sheltered dogs whilst they are held captive, the most effective way to improve the long-term welfare of a sheltered dog is to ensure that the animal is adopted. Research indicates that a sheltered dog’s behaviour determines whether or not the animal will be regarded as desirable by

Ž .

potential buyers Wells, 1996 . Findings suggest that visitors to rescue shelters prefer Ž

dogs which are at the front rather than the back of the pen Wells, 1996; Wells and .

Hepper, 1992 , dogs which are alert, i.e. moving, standing, sitting, to those which are

Ž .

non-alert, i.e. resting, sleeping Wells, 1996 , and dogs which are quiet as opposed to

Ž .

barking Wells, 1996; Wells and Hepper 1992 . Unfortunately, sheltered dogs do not always exhibit publicly ‘‘acceptable’’ manners, and their chances of purchase are

Ž .

consequently at risk Wells, 1996 .

The cage environment of sheltered dogs may also influence whether or not an animal Ž .

prefer dogs which are housed in what they perceive to be complex and stimulating environments. Thus, dogs which are housed in cages which have their beds visible to the

Ž .

public are much preferred to those dogs which are held in empty cages Wells, 1996 . The mere presence of a toy in the dog’s pen may also promote more positive perceptions

Ž of dog desirability, even if the animal is not actually viewed playing with the toy Wells

. and Hepper, 1992 .

By designing cages which encourage dogs to behave in publicly ‘‘acceptable’’ manners and which help to make dogs look more attractive to prospective owners, it may be possible to improve potential buyers’ perceptions of dog desirability and increase the number of animals which are purchased from rescue shelters. The following

Ž .

study examined the behaviour of sheltered dogs in response to: 1 increased human

Ž . Ž . Ž

contact social stimulation study ; 2 the addition of a bed to the front of the pen bed

. Ž . Ž .

study or; 3 the addition of a toy to the front of the animal’s cage toy study , to determine whether any of these environmental changes influenced dog behaviour in ways that could be perceived as desirable to potential dog buyers, andror improved a dog’s chances of becoming purchased.

2. Method

2.1. Study site

The main branch of the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals ŽUSPCA , in Carryduff, Down, was used as the study site. Dogs housed in this shelter. are generally held singly in two rows of cages, 29 cages per row. The centre is thus

Ž

capable of housing a total of 58 dogs singly at any one time. Each cage 1 m wide=4 m .

long=2 m high consists of a wire mesh front, a door at the back of the pen, and concrete floor and walls. The dog’s view from the front of the cage is of a concrete walled alley along which members of the public may walk. The enclosures are cleaned every morning and the dogs are fed once a day in the afternoon.

2.2. Experiment 1: the effects of enÕironmental change on the behaÕiour of dogs housed in a rescue shelter

This study examined the influence of environmental change on the behaviour of sheltered dogs to determine whether the cage manipulations encouraged dogs to behave in more publicly ‘‘acceptable’’ manners.

2.2.1. Subjects

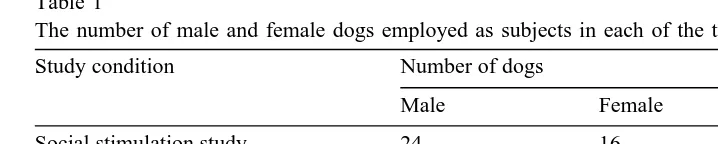

Table 1

The number of male and female dogs employed as subjects in each of the three study conditions and overall

Study condition Number of dogs

Male Female Total

Social stimulation study 24 16 40

Bed study 17 23 40

Toy study 13 27 40

Total 54 66 120

was therefore unavailable. Only those dogs on their 3rd, 4th, or 5th days of captivity were employed as subjects, since dogs on their first day in the shelter tend to behave

Ž

differently to those which have been in captivity for longer than 24 h Wells and .

Hepper, 1992 .

2.2.2. Procedure

The procedure for recording the dogs’ behaviour was exactly the same in all three studies. The behaviour of each dog was recorded over a 4-h period using a scan

Ž .

sampling technique e.g. Martin and Bateson 1986 . At 10-min intervals the experi-Ž .

menter DLW approached the front of each subject’s cage and recorded the dog’s behaviour as soon as she saw the animal.

Ž

Three separate aspects of behaviour all known to influence public perceptions of dog

. Ž .

desirability; Wells, 1996 were recorded at each observation, namely: 1 Position in the

Ž .

cage front, middle, back . Wire meshing on top of the concrete walls, and running the length of the dog’s cage, in both shelters, allowed the experimenter to immediately determine which section of the cage the dog happened to be in at each observation. The front of the cage was defined as the section closest to the experimenter, whilst the back

Ž .

of the cage was defined as the section furthest away from the experimenter; 2 ActiÕity Žstanding dog is supported upright with all four legs , sitting dog is supported by thew . Ž

. Ž

two extended front legs, and two flexed back legs , resting dog is reclining in a ventral . Ž

or lateral position, eyes open , sleeping dog is reclining in a ventral or lateral position,

. Ž . Ž .

eyes closed , moving dog is walking, running, or trotting about the cage ; 3

Ž w x w x w

Vocalisation barking self descriptive , quiet no vocalisation , other includes whining, x.

growling, whimpering . Each dog was studied for a period of 4 h, every 10 min, providing 24 observations of the dog’s position in the cage, activity, and vocalisation. Each behaviour was treated separately. For each behaviour, the number of times the

Ž

dog was observed in each category i.e. for Position in the cage: front, middle, back; for Activity: standing, sitting, resting, sleeping, moving, and; for Vocalisation: barking,

.

quiet, other was summed across the 4-h observation period.

2.2.3. Study conditions

2.2.3.1. Social stimulation study. Over the course of a week the number of visitors to the study site varied from day to day. To examine the influence of increased social

Ž .

Ž .

Sunday social condition , the day of the week that sees the greatest number of visitors

Ž . Ž .

to the shelter mean number of visitorss47 and on a weekday control condition ,

Ž .

when visitors to the shelter are much fewer in number mean number of visitorss12 . Each dog was studied in both the social and control conditions. The order of testing was counterbalanced.

2.2.3.2. Bed study. To examine the influence of moving the dogs’ bed to the front of the

Ž .

pen on dog behaviour, the subjects see Table 1 were studied on a day whenever the

Ž .

bed was placed at the front of the cage bed condition and on a day whenever the bed

Ž .

remained in its usual position at the back of the cage control condition . Each dog was studied in both the bed and control conditions. The order of testing was counterbalanced.

Ž .

2.2.3.3. Toy study. A gumabone chew Nylabone Products, Waterville, PO7 6BQ, UK was employed as the stimulus toy, since there is evidence that captive dogs enjoy toys

Ž .

they can chew DeLuca and Kranda, 1992; Hubrecht, 1993, 1995b . The toy was suspended from the front of the cage by a chain in order to prevent its contact with faeces, disinfectant, etc.

To examine the influence of adding the toy to the front of the dogs’ cage on their

Ž .

behaviour, the subjects see Table 1 were studied on a day whenever the toy was

Ž .

suspended at the front of the cage toy condition and on a day whenever the toy was not

Ž .

present in the cage control condition . Each dog was studied in both the toy and control conditions. The order of testing was counterbalanced.

2.2.4. Data analysis

Ž The analysis was performed separately on each of the three behaviours examined i.e.

.

position in cage, activity, vocalisation and was identical for each of the three studies

Ž .

conducted i.e. social stimulation, bed, and toy studies . Three mixed-design ANOVAs Že.g. Howell, 1992 were conducted for between subjects factor of dog sex male,. Ž

. Ž

female , and within subjects factor of dog behaviour, e.g. position in the cage front, .

middle, back , for each of the three studies.

2.3. Experiment 2: the effects of enÕironmental change on the incidence of dogs purchased from a rescue shelter

This study examined the influence of manipulating the cage environment of sheltered dogs on the incidence of dogs purchased from the study site.

2.3.1. Procedure

Information regarding the incidence of dogs purchased prior to and throughout three Ž

environmental manipulations i.e. the addition of a toy or bed to the front of the cage, .

and increased human social contact was collected from USPCA reports.

Thus, for the toy study, the incidence of dogs purchased whilst there was a gumabone

Ž .

chew present at the front of the cage throughout a 1-month period toy condition was compared to the incidence of dogs purchased from cages devoid of toys exactly 1 year

Ž .

previously control condition .

Similarly, for the bed study, the number of dogs bought during a 1-month period

Ž .

whilst there was a bed at the front of the animals’ cages bed condition was compared to the incidence of dogs sold exactly 1 year earlier whenever the dogs’ beds were at the rear of the pen.

Since sheltered dogs are generally only exposed to visitors on an irregular basis, particularly on weekdays, the social stimulation study examined whether more regular contact with humans would have an impact on the number of dogs bought from the study site. To investigate this, the incidence of dogs purchased during a 1 month period

Ž .

whenever one of the experimenters DLW was present in the shelter on a daily basis throughout opening hours, and made herselfÕisible to each of the dogs every 10 min by

Ž .

walking in front of the animals’ cages social condition , was compared to the incidence of dogs sold 1 year previously when dogs were not exposed to a similar level of

Ž .

consistent social stimulation control condition .

To allow for a comparison in the incidence of dogs purchased during the three study Ž conditions, all of the manipulations were conducted between September to November 1

.

month for each study , when the incidence of dogs sales from the USPCA tend to be very similar.

2.3.2. Data analysis

Ž .

A two-tailed paired t-test e.g. Robson, 1973 was conducted to determine whether the environmental manipulations exerted an effect on the incidence of dogs purchased from the study site. Simple descriptive statistics were also conducted to determine whether the incidence of dogs purchased differed according to the type of environmental manipulation.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: the effects of enÕironmental change on the behaÕiour of dogs housed in a rescue shelter

The results of the analysis on the effects of the three study conditions on the dogs’ position in cage, activity, and vocalisation are presented separately below. Only signifi-cant findings are reported.

3.1.1. Position in the cage

Table 2

Ž .

The mean number of times "s.e. that dogs were observed in each position of the cage during the three study conditions

Study condition Dog’s position in cage

Front Middle Back

Social stimulation study

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Social condition 10.32 "1.35 0.65 "0.19 13.02 "1.38

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 5.03 "1.11 0.40 "0.14 18.58 "1.16

ŽF 2,76w xs31.74, P-0.001. Bed study

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Bed condition 10.10 "1.46 0.50 "0.13 13.35 "1.46

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 5.60 "1.13 0.47 "0.13 18.12 "1.18

ŽF 2,76w xs7.48, Ps0.001. Toy study

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Toy condition 7.97 "1.33 0.47 "0.13 15.55 "1.35

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 6.32 "1.19 0.30 "0.08 17.38 "1.21

ŽF 2,76w xs3.10, n.s..

3.1.2. ActiÕity

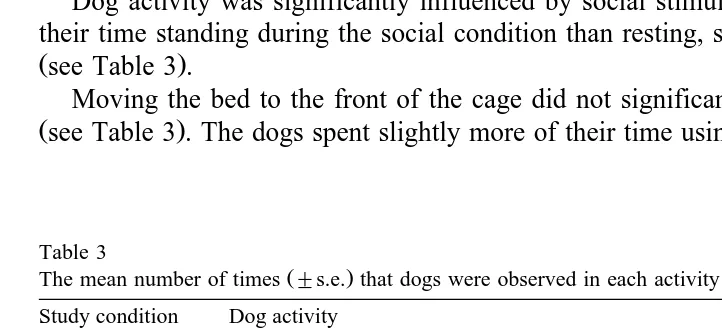

Dog activity was significantly influenced by social stimulation. Dogs spent more of their time standing during the social condition than resting, sitting, moving, or sleeping Žsee Table 3 ..

Moving the bed to the front of the cage did not significantly alter the dog’s activity Žsee Table 3 . The dogs spent slightly more of their time using the bed whenever it was.

Table 3

Ž .

The mean number of times "s.e. that dogs were observed in each activity during the three study conditions Study condition Dog activity

Standing Resting Sitting Moving Sleeping

Social stimulation study

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Social condition 14.23 "1.34 5.57 "1.24 3.58 "0.83 0.62 "0.22 0

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 8.82 "1.23 10.95 "1.41 3.58 "0.83 0.30 "0.13 0.35 "0.17

ŽF 4,152w xs11.64, P-0.001. Bed study

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Bed condition 11.75 "1.30 7.50 "1.29 4.57 "0.9 0.12 "0.05 0.05 "0.03

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 10.77 "1.49 9.07 "1.5 3.85 "0.84 0.10 "0.05 0.20 "0.14

ŽF 4,152w xs0.57, n.s.. Toy study

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Toy condition 10.90 "1.35 8.75 "1.28 3.90 "0.83 0.25 "0.09 0.22 "0.23

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 12.12 "1.4 7.88 "1.34 3.78 "0.81 0.05 "0.03 0.17 "0.18

Ž . placed at the back of the cage mean number of observationss6.1, s.e.s0.96

Ž .

compared to the front of the cage mean number of observationss5.0, s.e.s1.26 , but Ž w x .

this difference was not significant F 1,38 s0.44, n.s. .

Dog activity was not significantly influenced by the addition of a toy to the front of the animal’s pen. Most of the dogs spent several seconds sniffing the toy when it was

Ž . Ž

introduced into the cage; however, only 7 of the 40 dogs 17.5% actually used it i.e. .

very briefly chewed, pawed at, tugged the toy . Dogs were recorded using the toy for a Ž .

mean of 1.25 s.e.s0.65 observations.

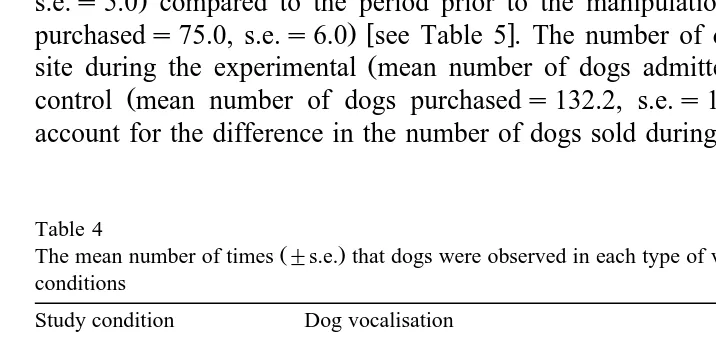

3.1.3. Vocalisation

Social stimulation significantly influenced dog vocalisation. Dogs spent more of their time barking during the social condition than the control condition. Neither the presence

Ž of a bed nor a toy at the front of the pen significantly influenced dog vocalisation see

. Table 4 .

3.2. Experiment 2: the effects of enÕironmental change on the incidence of dogs purchased from a rescue shelter

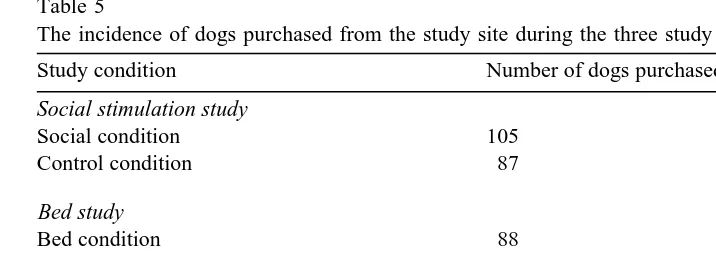

Ž .

Significantly paired t-tests5.42, P-0.05 more dogs were purchased during the Ž

period of the environmental manipulations mean number of dogs purchaseds97.7,

. Ž

s.e.s5.0 compared to the period prior to the manipulations mean number of dogs . w x

purchaseds75.0, s.e.s6.0 see Table 5 . The number of dogs admitted to the study

Ž .

site during the experimental mean number of dogs admitteds130.0, s.e.s5.7 and

Ž .

control mean number of dogs purchaseds132.2, s.e.s11.6 conditions could not account for the difference in the number of dogs sold during these study periods.

Table 4

Ž .

The mean number of times "s.e. that dogs were observed in each type of vocalisation during the three study conditions

Study condition Dog vocalisation

Quiet Barking Other

Social stimulation study

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Social condition 21.82 "0.5 1.55 "0.45 0.43 "0.28

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 23.40 "0.29 0.38 "0.28 0.22 "0.1

ŽF 2,76w xs7.42, Ps0.001. Bed study

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Bed condition 23.80 "0.1 0.22 "0.1 0 "0

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 23.90 "0.05 0.05 "0.03 0.05 "0.03

ŽF 2,76w xs1.77, n.s.. Toy study

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Toy condition 23.33 "0.45 0.45 "0.43 0.22 "0.18

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Control condition 23.20 "0.54 0.57 "0.52 0.22 "0.16

Table 5

The incidence of dogs purchased from the study site during the three study conditions

Study condition Number of dogs purchased

Social stimulation study

Social condition 105

Control condition 87

Bed study

Bed condition 88

Control condition 69

Toy study

Toy condition 100

Control condition 69

Ž . Ž .

Specifically, more dogs were purchased during the social ns105 and toy ns100 Ž . w x

conditions than during the bed condition ns88 see Table 5 . USPCA reports indicated that dog sales were similar to those during the control conditions 1 month prior

Ž . Ž

to mean number of dogs purchaseds74.0, s.e.s5.2 and 1 month following mean .

number of dogs purchaseds77.0, s.e.s6.7 the 3 months of the environmental manipulations.

4. Discussion

Findings from the above study indicate that certain environmental changes have a positive effect upon the behaviour of sheltered dogs, encouraging dogs to behave in more publicly ‘‘acceptable’’ manners and increasing their chances of becoming pur-chased.

4.1. The effects of social stimulation

Increased social stimulation had a positive effect on the behaviour of sheltered dogs, encouraging them to spend more of their time standing at the front of the pen. This change in behaviour may be considered largely advantageous from a welfare point of view, facilitating dog–human interactions and increasing the amount of stimulation a dog receives. Providing sheltered dogs with increased social contacts may also allow an

Ž .

animal to gain more control over its environment Hubrecht et al., 1992 , thereby decreasing the chances of the individual failing to cope with the pressures of confine-ment.

Standing alert at the front of the cage may also improve a sheltered dog’s chances of becoming purchased. Potential buyers show a much greater preference for dogs which

Ž

.

and Hepper, 1992 , and dogs which are alert, i.e. standing, sitting, moving, to dogs

Ž .

which are not alert, i.e. resting, sleeping Wells, 1996 . By exhibiting more publicly acceptable behaviours in the presence of larger number of visitors to the shelter environment, dogs may significantly improve their chances of being viewed as desirable and their ultimate chances of being re-housed.

Unfortunately, dogs showed a slightly greater tendency to bark in the presence of a larger number of visitors to the shelter. This may reflect negatively upon potential dog

Ž

buyers given their preference for dogs which are quiet Wells, 1996; Wells and Hepper, .

1992 . On a more positive note, the increase in barking during the condition of social stimulation was only slight, suggesting that sheltered dogs are used to the intermittent sight of humans. Furthermore, dogs may not necessarily bark at the visitors, but rather in response to the disturbance caused by the presence of a relatively large number of humans in the shelter.

4.2. The effects of moÕing the dogs’ beds to the front of the cage

Moving the dogs’ beds to the front of their enclosures resulted in the dogs spending more of their time at the front of the cage, despite using the bed slightly less in this particular position of the pen.

Dogs appear to want to spend time in the vicinity of their own bed, possibly regarding it as their own territory. Moving the bed to the front of the cage may be regarded by the dogs as a novel change to an otherwise predictable environment, encouraging them to investigate the modification.

The simple act of placing a dog’s bed at the front of the pen may indirectly improve Ž .

the welfare of sheltered dogs. Wells 1996 discovered that the public have a much greater preference for dogs which are viewed with a bed in the cage to those which have no bed in the cage, and findings from the present study suggest that the presence of a bed at the front of the pen can improve a dog’s chances of being adopted. This is an issue which could be easily addressed by most animal shelters.

4.3. The effects of suspending a toy to the front of the cage

Very few of the dogs showed any interest in the addition of a toy to the cage. This concurs with previous work reporting that dogs housed in rescue shelters show little or

Ž

no interest in toys, possibly because there is no one to induce play Wells and Hepper, .

1992 .

Despite the dogs’ lack of enthusiasm towards the cage stimulus, it may still be in their best interests to have such an item present in the cage, even if it is not utilised.

Ž .

Wells 1996 reported that potential buyers prefer dogs which have an enrichment item Žin this case, a toy ball in the cage to dogs which are held in a barren pen, even if the.

Ž .

encourage potential buyers to view the dog within the pen as a desirable pet rather than an unwanted animal. Obviously shelters are constrained as to what toys they can place into a dog’s cage because of the ease of disease transmission between dogs. Given the fact that very few sheltered dogs seem to make any use of a cage toy however, simply suspending a toy from the front of a dog’s cage so that it is within the view of the visitors, may serve to indirectly improve the dogs’ welfare by enhancing the public’s perceptions of the caged animals.

A comparison of the effects of the three environmental manipulations revealed that social stimulation exerted the greatest influence on dog behaviour, encouraging dogs to behave in a more publicly acceptable manner. Social stimulation also exerted the most notable impact upon dog sales, resulting in a greater increase in the incidence of dogs purchased compared to the addition of a toy or a bed to the front of the pen. Unfortunately, rescue centres cannot always rely on large numbers of visitors to their shelters. As this study has demonstrated, however, it may only take a very small increase in human–dog interactions to promote more publicly acceptable dog behaviour and improve the animal’s chances of subsequent adoption. By restricting shelter opening hours it may also be possible to increase the number of visitors in the dogs’ environment at any one time, thereby increasing the chances of dogs exhibiting more publicly acceptable behaviours and improving their chances of subsequent adoption.

Ž

Modifying the cage environment in simple and cost-effective ways e.g. adding a .

toyrbed to the front of the pen may also have positive implications on a sheltered dog’s chances of becoming re-homed. By increasing the complexity of the cage environment it may be possible to stimulate interest from passersby and also encourage dogs to behave in more publicly acceptable manners. As this study has demonstrated, these changes can improve the chances of a sheltered dog becoming purchased by a new owner.

It must be borne in mind that a wide variety of factors may influence the desirability of a sheltered dog in addition to the animal’s cage environment, e.g. its sex, age, breed,

Ž .

colour Wells 1996; Wells and Hepper 1992 . It was not possible to control all of these factors during the study. USPCA reports, however, indicated a relative consistency in the types of dogs admitted to their shelters every month, suggesting that the increase in the number of dogs sold during the experimental conditions in Experiment 2 were due largely to the environmental manipulations as opposed to any other factor pertaining to the animal.

Many rescue organisations are now paying more attention to the cage environment of sheltered dogs and the important relationship between cage design, dog behaviour and public perceptions of dog desirability. The on-going research in this area will hopefully ensure that developments continue to be made in our understanding of how to ideally house sheltered dogs in order to promote their welfare whilst in captivity and improve their chances of becoming purchased.

Acknowledgements

this research to be undertaken. D.L.W. acknowledges the financial support of the European Social Fund.

References

DeLuca, A.M., Kranda, K.C., 1992. Environmental enrichment in a large animal facility. Lab. Anim. 21, 38–44.

Hetts, S., Clark, J.D., Calpin, J.P., Arnold, C.E., Mateo, J.M., 1992. Influence of housing conditions on Beagle behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 34, 137–155.

Hite, M., Hanson, H.M., Bohidar, N.R., Conti, P.A., Maltis, P.A., 1977. Effect of cage size on patterns of activity and health of Beagle dogs. Lab. Anim. Sci. 27, 60–64.

Howell, D.C., 1992. Statistical Methods for Psychology. 3rd edn. Duxbury Press, CA.

Hubrecht, R.C., 1993. A comparison of social and laboratory environmental enrichment methods for laboratory housed dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 37, 345–361.

Ž .

Hubrecht, R.C., 1995a. The welfare of dogs in human care. In: Serpell, J. Ed. , The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, pp. 180–198. Hubrecht, R.C., 1995b. Enrichment in puppyhood and its effects on later behaviour of dogs. Lab. Anim. Sci.

45, 70–75.

Hubrecht, R.C., Serpell, J.A., Poole, T.B., 1992. Correlates of pen size and housing conditions on the behaviour of kennelled dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 34, 365–383.

Hubrecht, R.C., Turner, D.C., 1998. Companion animal welfare in private and institutional settings. In:

Ž .

Wilson, C.C., Turner, D.C. Eds. , Companion Animals in Human Health. Sage Publications, London, pp. 267–289.

Hughes, H.C., Campbell, S., Kenney, C., 1989. The effects of cage size and pair housing on exercise of Beagle dogs. Lab. Anim. Sci. 39, 302–305.

Martin, P., Bateson, P., 1986. Measuring Behaviour. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Mertens, P.A., Unshelm, J., 1996. Effects of group and individual housing on the behaviour of kennelled dogs in animal shelters. Anthrozoos 9, 40–51.¨

Robson, C., 1973. Experiment, Design, and Statistics in Psychology. Penguin Books, London.

Wells, D.L., 1996. The welfare of dogs in an animal rescue shelter. PhD Thesis. School of Psychology. The Queen’s University of Belfast, UK.