Table

of

Contents

Keynote Papeis

1.

Ludger Deitmer, Germany, Design and evaluation of work place learning partnerships in VET (1-10)2.

RupertMaclean, Hongkong, Vocationalisation of Higher Education: lssues and Challenges (11-18)3.

Wahid Razzaly, Malaysia, The Development of Competency of Vocational Teachers in Malaysia:Curriculum Development

Perspective

(t9-2714.

Zhiqun Zhao, China, Current development and problems of vocational education in China (28-34)Theme 1: Concepts for Competence Development in TVET

1.

Asep Setiadi Husen, lndonesia, lmplementation Concept of Training Management for IndustrialSector Human Resources

Development

(35-44)2.

Danny Meirawan, lndonesia, Behavior Schools Partnership with the World of lndustries and Business in lmplementation of the Dual System Education (45-54)3.

Fouziah Mohd, Ramlee Mustapha, Malaysia, The lnfluence of Personal and Contextual Aspects on Career Decision Making of Malaysian Technical Students (55-63)4.

lsma Widiaty, lndonesia, SDL (self Directed Learning) Through e- Learning Based on e-Pedagogy Principals for pre-Service Teacher in TVET (64-7215.

lwan Harianton, Agus Suryana Saefudin, lndonesia, Alternative approach to deliver competencehigher skills technicians from diploma program in lndonesian higher educations toward global

competition

(73-81)6.

Jailani Bin Md. Yunos,Tee Tze Kiong,Yee Mei Heong, Malaysia, The Level of Higher OrderThinking Skills for Technical Subject in

Malaysia

(82-90)7.

Jaja Kustija, lndonesia, Study Analysis of Curriculum Models For TVET Teacher Education(s1-ee)

8.

K lma lsmara, lndonesia, Health and Safety Performance in SMK Yogyakarta (100-107)9.

Mahazani bin Ali, Malaysia, Development of a New Empirical Based Competency Profile for Malaysian Vocational Education and Traininglnstructors

(108-117)10. Siscka Elvyanti, Wan Azlinda binti Wan Mohamed, Malaysia, lndonesia TVETTeacher

t4_

15.

11. Fulvia Jordan, US, A case Study on Agroforestry Education: seeking a paradigm for the

Sustainable Development of Rural Youth in Darien, Rep. of Panama 1474-483) 12. Han Xu, Shijie Song, China, The survey and research ofthe participation of enterprises in the

practical teaching of secondary vocational school (484-4921

13. lskandar Muda Purwaamijaya, Rina Marina Masri, lndonesia, Learning Development of Third

Engineering Mechanic by Structural Analysis Assisted Computer foi lncreasing Understanding of

Civil Engineering Students (493-s02)

Johar Maknun, M. Syaom Barliana, lndonesia, Analysis of Teacher Education lnstitutions (LPTK)

capability To support lncreasing Proportion of Vocational High school (sMK) students (s03-s08)

Kai GlelBner, Diana Nikolaus, Germany, Teacher training in lndonesia with a focus on

Sustainable Development - Concept for a Joint Project between the OvGU Magdeburg and p4TK Medan (s0s-s16)

,u.W,',{oonesia,DoesltPaytolnVestinVocationalEducation?:AnEmpirical

Evidence from lndonesian Data (s17-s25)

Mohd Ali Jasmi, Mohd Amin Zakaria, Sahul Hamed Abdul Wahab, Malaysia, perception of

Lecturers on Workload in Relation to Effectiveness in Teaching and Learning at Polytechnics

(s26-s33)

Mohd Amin zakaria, Norani Mohd Noor, Mohd Ali Jasmi, Malaysia, culinary Art Education : A Demanding Profession ln Culinary Tourism for Malaysian's New Economy

Niche

(534-s42)

Mumu Komaro, Amay Suherman, Yayat, lndonesia, Comparative Study of lmproving TVET

Student Learning Outcome using Competency-Based Module with Teacher centre at the Initial of a Different Ability (s43-ss0)

20. Norman Lucas, UK, Researching the Learning of TVET teachers in the workplace (ss1-ss6)

21. Ramlee Mustapha, Norhazizi Lebai Long, Fouziah Mohd, Malaysia, Career Decision Process among Women in Technical Fields (ss1-s6s)

22. Sahul Hamed Abdul Wahab, Mohd Amin Zakaria, Mohd Ali Jasmi, Malaysia, Transformational of Malaysian's Polytechnic into University College in 2015: lssues and Challenges for Malavsian Technical and Vocational Education (s70-s79)

23. Soeprijanto, lndonesia, The Role of Cooperation Partners to the lmplementation of Synergic

Partnership Scope in Preparing Vocational Teachers (s7e-s8s)

24. Wahono Widodo, Agus Setiawan, lndonesia, lmproving Problem Solving Skill on Prospective Teachers of Vocational School in Foods Programs through

"MiKiR"

(596-593)1,7.

18

Proceedings of the 1"tUPl lnternational Conference on Technical and Vocational Education and

Trairtrg Bandung, lndonesia, 10-1 1 November 2O1O

Does

lt

Payoff

to lnvest

in

vocational

Education?:

An

Evidence

from

lndonesian

Data

Losina purnastuti

Un ive rsitas Ne g eri Yogya karta (yogya ka rta state U n ive rsity) UNY, Kampus Karangmalang yogyakarta SS2B1, lndonesia

lpurnastuti@yahoo.com

Abstract

This paper compares estimates

of the

rateof

returnsto

schooling for workersGeneral

Senior

Secgldav

School

(GSSS)and

workers graduatedfrom

Vocationd Secondary School (vsSS). Utilising data from lndonesia Famil! Life Survey 4,thi;

papera the returns to general education and vocational education intnoonesi;;;;

ir,"

rrii,i#r;,,

function model' The estimates of the returns to education show that, in gJneral, thoseir

educationare not

likelyto

earn more than thosein

vocational education. This resultd

support the commonly held assumption that private returns to general education exceed returns to vocational education.

lntroduction

The

impetusfor

this

study arose fromthe

debateon

the

relative benefits of educationand

of

general educationthat

is

still

ongoingin

developing corntries, lndonesia. scholars have consistently raisedquestionsiuolt

the utility of Jducational invrin vocational education. Many studies show that, in

general, vocational education has lower

to

educationthan

general education.This

leads1o

the

generally accepted viewthat

rsecondary schooling is

a

better investment forthe

individrial [seepsachl.p"rr",

ig?i,

Using the lndonesian Family Life Survey - Wave

4

(zoozl2ooa;, tl.is stuoy aoosevidence

b

debate, identifiesthe

individual gainsfrom

educaiion,and

sheds,on.'l

tigr,ton the dsl

between vocational and general education advocates.

The

restof

this

paperis

organisedas

follows. Section2

presentsa

brief descriptirr vocational senior secondary schools in lndonesia. section 3 provides a critical literaturerevier

previous empirical studies. Section4

briefly describesthe data

and econometric rSection 5 discusses the results. The final section then offers some concluding remarks.

2

Briel Description on Vocational secondaryschools

in lndonesiaTechnical

and

vocational educationhad taken

into

operationin

lndonesia before proclamationof

independence.The

main purposeof

the

education

*as

to

providethe

ba knowledge and skills needed by lndonesian people. At that time, the knowledgeand the levd skills supporting national development were not taken into account. Before inde"pendence,

in lndonesia were classified as schools for women, schools of engineering, schools of aqri and schools of commerce. After independence, schools were classified as schools of house affairs,,engineering education, and agriculture education [Soenaryo et

al.

2oo2).Today, vocati secondary schools are classified as schools of agricultuie and fbrestry, tecrrnotogy and indusfiy6business and management, social/community welfare, tourism, arts and handicrafts, health,

ard

marine. Briefly, the structure of the education system in lndonesia can be oulined as follows.

P*ft*idiksc? **k+*Falt $s}:**l *dx*at6*n

F***i+$iic*,"! l"u*r 5allc*t*lr

**{-i} f-S*h{}m* ll*u***i*lv

{+ rtcr,:'r*l .l:f,:.,l*tr

#+rtfurfi?#f fr+j;:l*tulr!

fi ti

I

t[*rw*r#, .I Sp#r*#*k*+#rri l

?i

li li

; Sr*,€t{ i

t:

I

.FiF*&irtf, at:

tl

N

N" "'

:tf r Bi[ l*'! :H *' '.8 C

i;

sI*'''

ffir

tr*k*t a t&Er**l *

ltdExre*A !

S*rrn*e.;n I

Fi'ey Sr**r* :

i- --:*,1-"i

I I8&*A Pr&f;Saf, !

I &n*h r

l&rr***u*rr* l

i.., ..., _,..,_.,, -",i

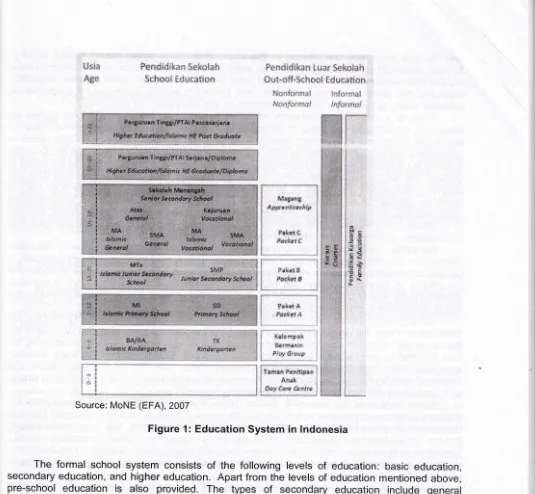

[image:5.595.28.563.13.507.2]Source: MoNE (EFA), 2007

Figure 1: Education System in lndonesia

The formal school system consists

of the

following levelsof

education: basic education, secondary education, and higher education. Apart from the levels of education mentioned above,pre-school education

is

also

provided.The

types

of

secondary education include general secondary school, vocational secondary school, religious secondary school, service secondaryschool,

and

secondaryschool.

General

secondary educationgives

priority

to

expanding knowledge and developing students' skills, and preparing them to continue their studies into highel education. Vocational secondary education gives priority to expanding specific occupational skills,and

emphasizesthe

preparationof

studentsto

enter

the

world

of

work and

to

lifting their professional aspirations. Vocational Education in lndonesia starts in the senior secondary school-grades 10,11,12 or 13.

3

Literature Reviews and Previous Empirical StudiesThe human capital model is the model most widely used to explain the relationship between education and labour market outcomes. lt was first introduced by Adam Smith

in

1776 in his bookThe

Wealthof

Nations. However,the

recent popularityof the

modelis

due

largelyto

the developments by Schultz [1961], Becker 119621, and Mincer 119741. The coreof

Human Capitat Theory (HCT)is the

ideathat

investmentsare

madein

human resourcesin

orderto

improve productivity, and therefore employment prospects and earnings. ln the human capital model, an individual invests time and forgone earnings in order to obtain higher future benefits. The primary means of assessing the value of the educational investment is the internal rate of return. A number of methodologies have been proposed to evaluate the magnitude of the return to schooling, but thef*.tjg* r{

, &ri**rt

one that has become

a

cornerstonein

this empirical research isthe

human capital eamiqgr function proposedby

Mincer 119741in

his study Schooling, Experience and Earnings.ilfrur

argues

that

investmentsin

human capital taketwo

complementary forms: formalschooQ"

measured

by

yearsof

school completed; and on-the-job training, which canbe

measuredfi

potential years inthe

labour force subsequentto

the

completionof

schooling.There is

a

vast bodyof

research on returnto

schooling. However, empirical studiesm

returnsto

schoolingin

the

caseof

lndonesiaare

sparse, particularly studiesthat

focusc

vocational education.This

section reports summariesof

selected researchon the

retumb

vocational education. With regard to both developed and developing countries, the focus intis

instance is on establishing the conventional wisdom with respect to the magnitude of the retumb

general and vocational education.

Six

studiesare

covered here. Psacharopoulos [1994]ad

Bennell [1996] reviewthe

returnto

general and vocational education using data fromvarixr

countries. Dearden et al. 120021 and Sakellariou [2003] evaluate the private return to generalad

vocational education in developed countries, namely Britain and Singapore, respectively.Moer**

et al. [2003] and El-Hamidi [2006] examine the private return to general and vocational educatin

in developing countries, namely Thailand and Egypt, respectively.

Generally, the literature that compares

the

returnto

vocational and academic educatincomes from less developed countries. Psacharopoulos [1994] reviews rates of return estimates

b

general and vocational secondary education from 24 countries. This review provides evidencetH

the

returnsto

general education are larger than returnsto

vocational education.In contrat

Bennell [1996] affirms that the average rates of return to general and vocational education:re

almost identicalfor Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Utilising data from the 1991 sweep of the National Child Development Study (NCDS) and

tlp

1998 Labour Force Survey (LFS), Dearden et al.120021 evaluate a comprehensive analysis oftln

labour market returnsto

academic and vocational education in Britain. Without considering the time investedto

acquire each qualification, Deardenet al.

120021 find that the wage premiunassociated

with

academic qualificationsis

typically higher thanthe

premium associatedwilr

vocational qualifications at the same level. However, after taking into account, the amount oftinp

taken to acquire different qualifications, the disparity narrows.Using data from

the

mid-1998 Labour Force Survey, Sakellariou [2003] examinestle

relationship between education and earnings in Singapore. This study utilises a Mincerian eamirgsfunction to estimate returns to formal and vocationalitechnical education. The main results suggest that the returns to vocational education (10.3 percent for secondary vocational education and 12-l

percent for post-secondary vocational education) are only slightly higher compared with the retune

to

formal education(9.4

percentfor

secondary formal educationand

1'1.3 percentfor

pos& secondary formal education).Moenjak et al. [2003] examine the relative returns between these two types of education

il

the

upper secondary levelin

Thailand. This study utilises data from Thailand's Labour Force Survey for the years 1989 to 1995. The OLS estimates of the Mincer earnings model suggestthd

upper secondary vocational education has higher earnings returns by 23.8 percent for men and20.7 percent for women, compared

to

general education at the same level. Furthermore, aftertaking into account possible self-selection and other factors, such

as

experience, marital and migration status,the gap

of

returnsto

education between vocational education and general education are even wider. Men with vocational education obtain returns to schooling 63.9 percenthigher than those

with

general education. Women with vocational educationgain

retums to schooling 49.4 percent higher than those with general education. lndeed, the overall resuhssuggest

that

investmentto

improve accessto

vocational education might proveto

be

more beneficial.Adopting Mincer's earning function, El-Hamidi [2006] identifies the relative returns between vocational and general education in Egypt. The empirical analysis of this study is based on a 1998 nationally representative household survey, the Egyptian Labour Market Survey (ELMS). ln order

to reduce self-selection bias, the author includes control variables that might capture part of the unobserved components in the error term such as family background characteristics. To solve the

problem

of

sample selection bias,the

2SLS approach,as

suggestedby

Heckman [1979],b

applied. The results indicate tlrat the private rates of returns to vocational secondary education are higher compared to general secondary education. The differences are 29.3 percent for men and 2.1 percent for

women.

,

h

and Econometric SpecificationDtta

The data to be used in the analysis were obtained from the lndonesian Family Life survey

-iJ[|.til^tl:-,Jlo:,?:,1.1"_:l,lr_

rcmrcand

hearth survey.The

!"_r,,"v iriiii"i"

,

continuins ronsitudinarsurvey coilects data

on

iroiriorrr'''r;;X#;Yr,

,n",,.P^".,:,[":":J"le:..t".communities

in_whicht"v-rir",'rnl"tn"

hearth and educationthev use. |FLS4 was fierded

in

rate 2oo7 and"rrry

zboa"r'ln"'=r1xl"1;isii:x1"d

fl:*:J*':il'j

rI'-1?rrq,hor"rords

andq+,toiind;iJu}.

*"r"

interviewed. 'e(]. tFLD4rFLS4a mllaborative effort by RAND, the center for Popuiation

ano poticy studies

(cpps)

of theersity of Gadjah Mada, and Survey Meter.

tftl

The Modetln estimatino returns to vocational and general education, the earnings function

method will

h

used' Both a Ystandard wtincerian;r9 *q"rr as an-'Lrg;"nt"d

Mincerian, specification of theffi;Jlnction

will be utilized. ln the standard specricaiion, returns to educaiion are estimated_\-.tlii

..-

/:c+

4.,)

i,r,_5.nitrr:.;_ +;?,8.i-._

.:,5.i:

+ ;:_J"*,:

{+where

Z

denotes a vector of variables that are held to capture the setof individual characteristics.

ln(E,) =

Fo*0,5,+FrW,+

B.EXI

+t,

(1)

flrere

Ei is log of monthly earnings, s; is the number.of years of schooling, EX1 is years in labour market or experience, EX;2 is expdrience squared, and eii

denotes the error term, which embodies

fte

effect of all of the determinants of wages or earningsbesides schooling and experience. The

ryecification

is

shown logarithmicallyin

orderfor

the"iegr"."o* io

be interpretedin terms of

nmarginal effects' ln this way index B is interpreted

as tre"rate of return to schooting. This semi-hgarithmic equation that

his

oeen'introouced byuincei llol+1is known;; th"

humancapital

enings

function' lt has been the basis of practically attreseaich on returns to education.

ln

orderto

allowfor

the estimated rateof

returnto

vary in termsof

levelof

schooling,8$'ation (1) needed to be modified. To add an educationar revel dimension to th"

rr"rrg"

rate of retum concept, one can sub.stitutes

(the number of years of schoolingl*iir,

u""ries

of dummy uariables for different educational leveL, such as primary, selonoary, university, etc. The modified fitincerian earnings function is:ln(E,)=

Bo+l1rs.Dum,o

+ B,EX,+ B.EXI +e,

.

(2)nfiere s'Dum consists of dummies for levels of education. ln this specification, the private rate of returns to education to the kth level of education i"

""tirui"o'by

the following formula:,o

- ll"-i:{

:jj

nfrere B1 is the coefficient of a specific

'*i|ri

education, B1-1 is the coefficient of the previous tevetof education, and An is the diffeience in years

of

schoolinj-["t*""n

k and k_1.ln this paper, the standard Mincerian wage equation is augmented with the set

of individual characteristics summarized by Zi

(e.g.a

resilentiat oummylurban

or

rural), dummyfor

beingmarried' and dummy for provinces. 'Th]e augmented modified Mincerian earning

function is:

4.3

Estimation lssuesEstimates of returns to education using

a

simple/standard method (OLS) may suffgr several shortcomings. These include omissionof

relevant variables (omitted variable bias[endogeneity of schooling (endogeneity bias). Although several approaches to these problenrs been developed, this study does not fully benefit from them due to data limitations. Many st employ some relatively sophisticated methods, such as using proxies for unobserved utilising natural variation, and methods of exploring twins or siblings to handle the omitted rrai and endogeneity problems. However, many of the previous studies have provided evidence there are no significant differences between results obtained from innovative methods and

from the standard method. Thus, the majority of the empirical studies confirm that the method is a reasonably robust way to assess the link between schooling and earnings [see G

and Harmon 1999; Cheidvasser and Silva 2007; Comola and Mello 2010; Dufto ZOOi; Lam

Schoeni 1993; Miller et aI.20061

4.4

VariablesDescriptionTo

evaluatethe

returnsto

educationin

lndonesia,a

worker's specific human capild inapproximated by dummy variables to represent the levels of schooling of workers and by the

yean

of

potential experience. The dependent variable in the earning equation isthe

togbf

mr;rflf

earnings. There

are six

dummy variablesfor

education indicatingthe

level

of

educatinrd attainment, namely Primary School, Junior Secondary School, General Senior Secondary Sctrod Vocational Senior Secondary School, College, and University. An experience variable isindud

in the model since, ceteris paribus; workers with more years of job experience are likely toean

more. Higher experience is often associated with higher skills and higher productivity. We

defiret

worker's potential experience as his/her age minus the number of years of schooling, minus seugr, years' This is based on two assumptions. First, it is assumed that all individuals start schootirgil

seven years old. Second,it

is assumed that people get employed immediately aftercomptaig

school.

The

potential experience squared variableis

includedin

additionto

the

poteil-experience variable to capture the possibility of a non-linear relationship between experience

ad

earnings. ln general, differences in labour market conditions exist between rural and urban arelirc Control for these differences is achieved by including residential dummy (urban or rural) inilp

earnings equation. Other control variables in this respect include dummy for provinces inorderb

proxy

for

potential differencesin

education level, production structure, and other socialad

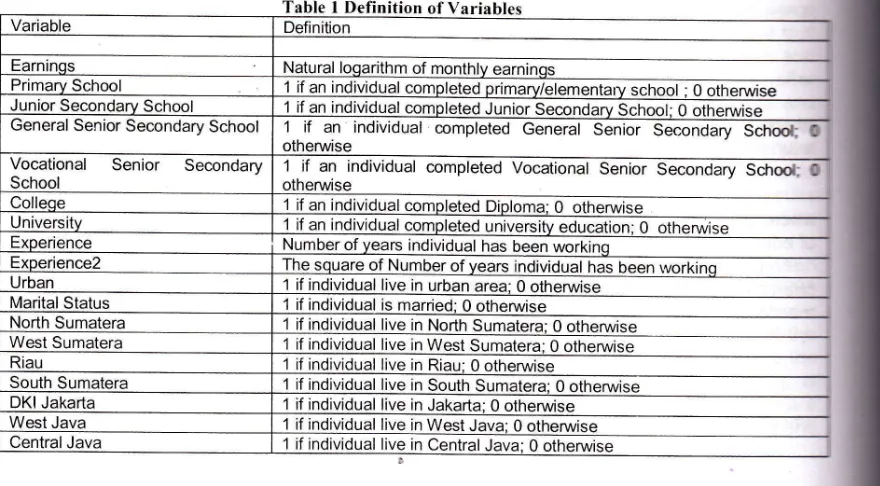

economic indicators. All the variables used in the analysis are defined in Table 1. Table I Definition of Variables

Variable Definition

Earninqs Natural logarithm of monthlv earninos

Primary School 1 if an individual completed primary/elementarv school : 0 otherwise Junior Secondarv School 1 if an individual completed Junior Secondary School: 0 otherwise General Senior Secondary School

1

if

an individual completed General Senior Secondary SChml; Ootherwise Vocational Senior Secondary

School

1 if an individual completed Vocational Senior SeconOary Scfro* O othenruise

Colleqe 1 if an individual completed Diploma; 0 otherwise

Universitv 1 if an individual corlpleted university education; 0 otherwise Experience Number of years individual has been workino

Experience2 The square of Number of years individual has been workino Urban 1 if individual live in urban area: 0 otherwise

Marital Status 1 if individual is married; 0 othenailse

North Sumatera 1 if individual live in North Sumatera: 0 otherwise West Sumatera 1 if individual live in West Sumatera: 0 otherwise Riau 1 if individual live in Riau; 0 otheruyise

South Sumatera 1 if individual live in South Sumatera; 0 otherwise DKI Jakarta 1 if individual live in Jakarta: 0 otherwise West Java 1 if individual live in West Java: 0 othenruise

Central Java 1 if individual live in Central Java; 0 otherwise

[image:8.595.111.551.526.769.2]Yogyakarta

East Java

Banten 1 if individual live in

Ban[en; 0 o

1 if indirridr ral lh,^ i^

Bali

South Kalimantan

-

t if individual live in South S 1 if individual live in WestSouth Sulawesi

West Sulawesi

5

Estimation Resultsln this section we present the study's empirical results assessing

the effects of vocational and general education on earnings . Table 2 shows the six regressions that will be

the basis for the analysis' There are three set oispecifications:

iil

rtrro"J'Mincerian

and augmented Mincerian estimate for all samples; (ii) standard Mincerian uno

,rg;"nted

Mincerian estimate for men; and

(iii) standard Mincerian and' augmented Mincerian estim"ate for women. gou"aiion

level, potential experience' and potential experience square explain

about 1B percent or

in"

changesin

logmonthly earnings for all workers and male workeri,

,nd-ii

percent for female workers. Education

level' potential experience, potential experience square,

Liation

dummy variable, marital status dummy variable, gender dummy variable, and provincial dummy variable explain about

27 percent of the changes in log monthly earnings for all workers, 23 percent for workers, and 29 percent for female workers' The coefficients for "most of the independent variables are statisiicatty significant and have the expected signs.

The coefficients of the education dummies all have the expected positive sign, and most of

them are significantly different from zero at

the

1 percent revel. Experlenc"#s

6e

expectedprofile'

A

positive signof the

experience variableindicates.

wgrfilo

experienceis

likely to contributeto

the growth of an individual's human"rpitJ.-Erh

additional year of experience isrelated to an increase in wages of about 1.4

-

L 9 percent. A negative"o"m"i"nt

of experience square as marginal returns from experience tend to decline over the lifetime. The results imply that, on average' there is a wage increase with experience until a peak at 30 years,and then a decline. All the coefficients of oulnmy for area

luiuanirurarl is positivJ

rhis

impries-t#t*Jrr."rs

berongingto urban areas obtain a higher benefii than workers belonging to rural areas. Another

interesting result from the earnings function estimates is that married w-orkers

are more llkely to receive higher earnings' The reason for this fact is probably because

,roi"J

workers have ahigher motivation to work harder and thus spend more time working since they

r",rr" to look after theiriamily.

The main difference between

the

results fromihe

standard Mincerian model andthe augmented Mincerian model

lie

in

the differencesin the

estimatesof

the

relative returns to vocational education as compared to general education. The results show that the coefficient of education level for vocational educati6n is higher ttrangenlral

education

fo;

;ii

specifications, unless the augmented model for men. The magnitudesoithe

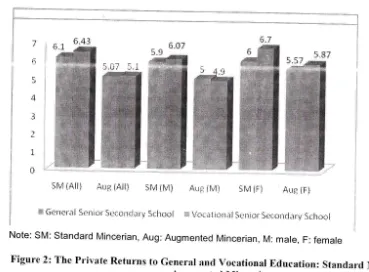

[image:9.595.62.484.85.160.2]estimated returns are lower for the augmented Mincerian approach. However, the differences are subfle.

Table 2 Estimated earnings equations (standard

Mincerian and Augmented Mincerian)

Alt Male

Female

Variable Standard Augmented

5.283 (272.90\*** Standard Augmented Constant 5.315 (315.82)*"* StanOard Auomented 5.380

(269.61)*. 5.275(231 .27)"** 0.10 (7.20\**"

5.234

(177.74\*** 5.091(146.67).. Primary

School

0.092

(2.58)**" 0.079(6.89)**" 0.104(7 .34\*** 0.019(0.89) 0.205 (8.02)"** 0,013 (1.s0) Junior Secondary School 0.228

(16.16)*** 0.194(14.34)"*. 0.216( 13.12)*""

0393

(23.99)*"*

0.1 94

(12.10)*". 0.194(7.79)** General

Senior Secondary School

0.411

(2g.gg)*** 0.346(25.12)**" 0.344(21.13r.. 0.385(14.73) 0.361 (14.01)***

Vocational Senior Secondary School 0.421 (27.07)**" 0.347

(22.79)*** (22.21)**"0.398 0.341(19.94)"** 0.406(14.06)***

0.370

(12.93r**

College 0.591

(0.22\*** 0.565(27.79\"** (20.89)"**0.585 0.530(19.28r 0.622(18.66)** 0.610(18.70)"** University 0.704

(39.17)*** 0.661(37.77\** 0.683(31 .47\**" 0.639(29.65)"** 0.730(23.93)"** 0.703(23.21\*** Experience 0.019

(19.62)"** (15.20)"**0.015 0.018( 1 6.31 ).

0.014

fi1.24\***

0.017

(10.69)"** 0.018(10.52)**" Experience2 -0.0003

(-17.47\**" -0.0003(-13.96)*** -0.0003(-14.60)*** -0.0002(-10.67)*"* -.0003(-9.70)*** -0.0003(-9.25)***

Urban 0.096

(12.03)*** 0.098(10.32)**" 0.921(6.26)***

Marital Status 0.081

(8.52)*"* o.117(9.09)*"* 0.026 (1.78)

North

Sumatera 0.106(5.91)*** 0.114(5.32)*** 0.092(2.89)***

West

Sumatera 0.1 (7.99)""*58 0.1 (7 .14\***68 0.138(3.87)"**

Riau 0.239

(5.60)*** 0.230(4.7 5\**' 0.259(2.93)*"* South

Sumatera {6.93)***0.148 0.1 (6.90)**"67 0.063(1.40)

DKI Jakarta 0.1 90

(1 1 .1 3)***

0.'165

(8.03)*"* 0.246(8.07)*""

West Java 0.062

(4.29\""* 0.040(2_31\** 0.114(4.25\***

Central Java -0.083

i-5.61)***

-0.073

(-4.1 0)**"

-0.086 (-3.26)*"*

Yogyakarta -0.059

(-3. 1 0 )***

-0.058

(-2.53)*" -0.045(-1.38)

East Java 0.008

(0.56) -0.010(-0.60) 0.059(2.17)**

Banten 0.187

(8.49)**" 0.110(4.20)"** 0.362(8.92)***

Bali o.042

(2.17\* 0.007 (0.32) o.120(3.52)*""

South

Kalimantan 0.124(6.51)**" o.134(6.08)"** 0.089(2.38r

South Sulawesi

-0.095

(-4.39)*** -0.102(-4.05)*** -0.790(-1.93y

West

Sulawesi 0.102(1.15) 0.204(2.04\** -.0245

G1.32\

Observations 12,840 12,840 8.675 8.675 4,165 4,165

R, 0.18 0.27 0.18 0.23 0.22 0.29

Source: Author's calculation

Note: Robust

t

statistics in*significant at 10% level.

parentheses; *** significant

at

1% level; **Significantat

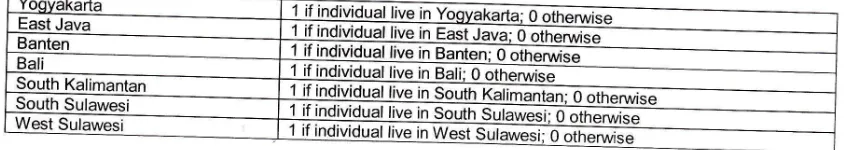

5% tevel:Turning to the private returns to schooling, in particular for general and vocational education, Figure

2

presents the findings. The private retumsto

schoolingfor

vocationaleducation are

generally slightly higher than those for general education. The retuins to schooling range between

5

-

6'1

percent and about 4.9-

6.7 percent for general educationand vocaional education, respectively.

on

average, the earning gap between general senior secondary school graduate workers and vocational senior secondary school grad-uate workersis

less than 1 percent.This figure does not support Psacharopoutos'[tss+1 coiclusion. Hence, this confirms Bennell,s t1996l argument, that the average rates of return to general and vocational education are very similar in the context of lndonesia.

5.07 5.1 r

.l

f,

:

,.

t:

:i

0r.

6

Concluding RemarksThe lndonesian Family Life survey-provides

an

opportunityto

estimate returnsto

general and vocational education in the context of'this particular country. Adopting the Mincerian earning function, this paper analyses the returns to general and vocational education study has shown that educationin

lndonesia. This significantly improves the earningsof

individuals. Moreover this study adds new evidenceto

the

debateon the

relative meritsof

vocational senior secondary education and of general education at the same level. Theresults challenge the common argument

that

a

general education provides higher returnsto

schoolingthan

vocational education.On average, the returns to vocational education and general education are almost identical.

This study only assesses the gross effect of

the

education pathway.with

additional data, providing a more detailed education track, it would be possibleto divide vocational education with more precision than the relatively global tracks (vocational) examining the differential returns

in that manner' Private returns to schooling, particularl'y return to general and vocational education,

is the focus for this study. However, it is widely perceived that

thl

effect of eoucaiion-is not onty private economic effects, but also externalities for individuals and society atlarge.

ft woufo be a valuable contribution to estimate the externalities of vocational education in further research.REFERENCES

Bennell, P (1996): "Generalversus vocationalsecondary

education in developing countries: a

review of the rates of return evidence", Journal of Development Studies, Vof -

ga,"pp

230-247. Callan, Tim and Harmon, Colm (1999): "The Economic Returnto

Schoolingin

lreland,,, Labour Economics, Vol. 6, pp. 543-550Sh,4

{.All}

ALrgiAtli

Srvlitvll

ALrg. itr,1} 5t!1iFi

ALrs iFli

ffi tlicnr..r;l 5enjor 5tcorrrJary School ::S \.ioi-:irtion.rlsrnior Sp1on{nrirSrjhoDl

i

i

rvrrrrrJgrilur rl.L.u[1tril\]

[image:11.595.60.429.101.373.2]Note: SM: Standard Mincerian, Aug: Augmented Mincerian, M: mare, F: femare

Figure 2: The Private Returns to General and vocational Education: Standard Mincerian

and

Augmented Mincerian

cheidvasser, sofia and silva, Benitez Hugo (2007): "The Educated

Russian,s curse: Returns to Education in the Russian Federation during the 1gg0s,,, Labour. yor.

21, No.

2.

pp.1_14comola' Margherita and Luiz de Mello (2009): "The Determinants_

of Employment and Earnings in

rndonesia", oECD Economics Department

wortinj

ea;;;;,

N;

690, oECD FuUii"ning Dearden, Lorraine., Mcrntosh, Steven.,Mv:\:

Michar and Vignores,Anna (2002):,,The Returns to Academic and Vocational Qualification in-Britain", pp.249-274 Bulletin oi'E"onomic Research, Vol. 54, No. 3

pu.flo, Esther

QaU):

"schooting and lndonesia: Evidence from an Unusual 91, No.4. Pp. 793-813.Labor Market Consequences

of

School Construction in Policy Experiment", The American Economic Review, Vol.El-Hamidi, Fatma (2006): ',General or Vocational schooling?

Evidence on school choice, Returns,

and '$heepskin' Effects fron: Egypt 19g8',

The Journal oi Foricy Reform vot.

9,

No. 2, 1 s7-176.Becker' Gary

s

(1962): "lnvestment in Human capital: A TheoreticalAnalysis, ,, Journat of potiticat Economy, Yol. LXX. pp. g - 4g.

Hawley' J'D (2003): "comparing the payoff to vocational and academic credentials

in Thailand over time". lnternationalJournal ot fOucaiionaf Oeveiop-men,l uo,. 23, pp.6ot_62s.

Lam' David and schoeni F. Robert (1993):

laT"^"r:.:, Famiry Background on Earnings and Returns

to schooling: Evidence from Brazil", Journal of Political Economy,

Vol. 101, No.

4.

pp. 710-740.Miller' Paul, Mulvey, charles, and Martin, Nick (2000): "The return to schooling: Estimates from a sampre of young Austrarian twins", Labour Economics" vot.

ig.

pp.571_587.

il#v;*

(97$:

schooling, Experience and Earnings. Nationat Bureau of Economic Research.Ministry of National Education (2007): EFA Mid Decade Assessment: lndonesia. EFA secretariat Ministry of National Education, nepuntic of lndonesia

Moenjak, Thammarak and worswick, christopher (2003): "Vocational education

in

Thailand: astudy of choice and Returns", Economics of Education nlriiew

, vor. 22. pp. 99_107. Psacharopoulos, G (1973): "Returns to Education: An

lnternational comparison

(san

Fransisco,CA, Elsevier, Jossey-Bass).

Psacharopoulos,

G

(1994): "Returnsto

investmentin

education:

a

global update,,, wortdDevelopment, Vol. 22, pp. 1325_1343.

sakellariou'

chris

(2003): "Ratesof

Returnto

lnvestmentsin

Formaland rechnical/Vocationat Education in Singapore,,. Education Economics, Vol.1f ,'frf".f

, pp.73_87.

schultz, T'

w

(1961): lnvestment in human capital, AmericanEconomic Review,March.

smith'

volumes Adam' 1776 I and rt. R. H. [1981]- campbeilAn

lnquiryinto the

Nature and causesof

the wealthof

Nations, and A. S. skinner, eds. linertv Fund: rndianoporis.soenaryo

et al,

(2002): sejarah Pendidikan Teknik dan Kejuruandi

lndonesia: Membangun Manusia Produktif, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, Direktorat Jenderal pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah, Direktorat pendidikan Menengah Kejuruan,

.lat<arta.