AN ANALYSIS OF TEACHERS’ QUESTIONS AND STUDENTS’ RESPONSES IN AN EFL READING COURSE

Vicorio Talentino

Faculty of Language and Literature Satya Wacana Christian University

Salatiga

Maria Christina Eko Setyarini Faculty of Language and Literature Satya Wacana Christian University

Salatiga

Abstract

Classroom interaction between a teacher and students always exists. Through their talk, teachers have an important role in maintaining an alive classroom interaction. One type of the teacher talk is teacher‟s questions, which are the most important tools that teachers have for helping students understand their learning materials. This paper investigated the types of teacher questions and students‟ responses. The subjects of this study were 3 EFL reading courses teachers and all students in 3 Academic Reading classes at the Faculty of Language and Literature, Satya Wacana Christian University. The study used a mixed method in collecting and analyzing the data. Different from the results of previous research, the findings of this study show that in all the classes, open and referential questions were frequently asked by the teacher, followed by closed and display questions and yes/no questions.

Keywords: classroom interaction, teacher talk, teacher question

INTRODUCTION

There are some benefits to maintaining classroom interaction, oral or written communication between a teacher and his/her students or students with students (Dobinson, 2001). The interaction becomes more crucial since they can develop students‟ communication skills (Hall, 2002) that benefits students socially and academically (Beyazkurk & Kesner, 2005). Hence, such interaction will increase students‟ opportunities to use English, as the target language, for their communication. Second, according to Hall and Walsh (2002), classroom interaction is one of the main indicators in which learning is accomplished in the classroom. Thus, I possibly think that the better the classroom interaction is, the better benefit that both students and teachers can obtain.

classroom interaction, teachers need to manage “teacher talk” that means some adjustments to both language forms and language functions to assist communication.

According to Qu (2011), there are four types of teacher talks. The first one is informative teacher talk, in which teachers deliver their opinion, facts, and concepts through their words. The second one is directive teacher talk, which functions to direct classroom activities running in a classroom. The third one is eliciting teacher talk, which aims to inspire students and get students‟ answers to some questions asked in a class. The last type is feedback to students‟ answer.

Teacher talk is a part of classroom interaction that can create a harmonious atmosphere and promote a more friendly relationship between teachers and students (Liu & Zhao, 2010). As my experience in following a teaching-learning process, when a class had a friendly teacher-students relationship and harmonious atmosphere, I would freely participate through every class discussion. However, not all teachers could maintain teacher talk that led to such atmosphere. As I noticed, my classroom participation depended on teachers who taught in a particular class. Turner and Patrick (2004) who found that the pattern of teachers‟ interactions affected students‟ participation strengthen my experience.

Nevertheless, one of the teacher talk strategies that teachers can do to maintain a successful classroom interaction is by asking questions. Some previous international studies have discussed the issues. On her study, Xu (2010) stated that, in most of language classrooms, a teacher asking questions and students answering the questions generate a major part of classroom interaction. As a category of input provided by a teacher, teacher questions shape an integral part of classroom interaction (Ho, 2005). In a more recent year, Yang (2010) investigates effects of the types of questions that teachers ask to the students‟ discourse patterns. She found that yes/no questions and closed and display questions were frequently asked by the teachers. Meanwhile, open and referential questions were rarely or even never asked. In the following year, Khan and Inamullah (2011) explore the levels of questions teachers asked during their teaching at secondary level using Bloom‟s taxonomy. The result of their study showed that teacher questions dominated classroom interaction. The study also found that most of the questions were low-level cognitive questions that were quite contrast with the higher-level cognitive questions.

The study done by Ho (2005) and Khan & Inamullah (2011) were the background information in conducting this research. Unlike the two studies, this study was conducted in an Indonesian context. Besides, it is considering not only the teacher questions but also the student responses, which is expected to provide insights for teachers on which types of questions should be more prioritized.

The aim of this study was to investigate classroom interaction in Academic Reading courses, especially the teacher questions and the student responses, to classify and to analyze the questions asked by the teachers by classifying the questions and students‟ responses into types of questions in Bloom‟s taxonomy of educational objectives (1956), as cited in Anderson & Krathwohl (2000). More specifically, this study attempted to answer the following research questions: [1] What are the types of questions frequently asked by the teacher? [2] What are the students’ responses toward teacher’s question?

LITERATURE REVIEW Teacher Questions

Commonly, questioning becomes a popular strategy for eliciting responses from students during a teaching and learning process. Teachers have some purposes in asking questions in a classroom. They are to test their students‟ previous knowledge, recall and recognize something, to think and reason about something, to elicit something from their students, to promote initiative and originality, to stimulate the interest and effort on the part of their students to focus attention on a particular issue, to develop an active approach to learning, and to keep children mentally alert (Raymond, 2004). Al-Aweiny (2002) states that questioning might be used to stimulate the curiosity of their students, to revise a lesson as well as to check whether their students are following the lesson or not, to link new aspects of knowledge with the previous ones, to create a type of cooperation among students, and to discover the weak points of their students. It would seem to indicate that teacher questions play an important role in managing classroom routines.

Three question categories (Tsui, 1995 as cited by Yang, 2010) were used in this study. They are [1] open and closed questions, [2] display and referential questions, and [3] yes/no questions. Firstly, open and closed questions are classified according to the kind of elicited responses. Open questions can have more than one acceptable answer. An example of this type of question is “What do you think of?” Meanwhile, closed questions only accept one possible answer. Secondly, display and referential questions are more on the nature of conducted interaction. These types of questions emphasize more on their purpose. In the display questions, teachers have already known the answer to their questions that aim to check students understanding. On the other hand, in referential questions, teachers have not known the answer to their questions.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

In analyzing the types of teacher questions and student responses, Bloom‟s (1956) taxonomy of educational objectives, as cited in Anderson and Krathwohl (2000) was used. According to Orlich (2004) as cited in Balasundaram and Ramadoss (2009), there are three domains in the Bloom taxonomy, namely affective, psychomotor, and cognitive educational learning objectives. However, due to the time limitation to conduct the study, this research only concerned the cognitive domain, as it has the closest relation to teacher questions types and students responses.

The Bloom‟s taxonomy components were arranged from the lowest to the highest order. The levels of categorization of this cognitive domain are knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Knowledge is recalling facts. Comprehension is describing in one‟s words. Application is applying information to produce some results. Analysis is subdividing something to show how it is put together. Synthesis is creating a unique, original product. Evaluation is making value decisions about issues. The first three levels of this system deal with lower-order thinking skills that are essential in laying the foundation for deeper understanding. The other last three levels employ higher-order thinking skills (Hopper, 2009).

referential questions, because the type of response is known but the actual response is not. In that case, students are free to respond in their way. Lower order questions are knowledge, comprehension and application based. They encourage lower levels of thinking. Higher order questions develop students‟ ability to analyze and evaluate critically concepts and ideas. Here, teacher question is very important to elicit students‟ level of thinking. The higher the level of questions is asked, the higher the students‟ level of thinking will be. A teacher must be able to frame questions that are challenging, structured open or referential questions with some minor information, and supports higher order thinking.

THE STUDY

This study employed a mixed method: quantitative and qualitative. According to Creswell (2003), researchers, for many years, have collected both quantitative and qualitative data in the same studies, but to put both forms of data together as a distinct research design or methodology is new. Other mixed methods writers emphasize the techniques or methods of collecting and analyzing data (for example, Creswell; Onwuegbuzie & Teddlie, 2003; Morse, 2003). Mixed method research involves both collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data includes closed-ended information that, for instance, is found in attitude, behavior, or performance instruments. In contrast, qualitative data consists of open-ended questions. In short, it is not enough to simply collect and analyze quantitative and qualitative data; they need to be “mixed” in some way so that they form a more complete picture of a problem.

Context of the Study

Due to the time limitation to conduct the study, the study was only focused on English teaching-learning processes in a classroom, Academic Reading, at English Language Education Program at Satya Wacana Christian University (ED-SWCU). The class is the last advanced level of reading courses in ED-SWCU. This course focuses on how to give critical responses to an academic journal articles. In the class, students need to have a deep critical thinking, since they have to give their opinions on a particular topic.

Research Participants

This study involved three English teachers from three different Academic Reading courses at ED-SWCU. Besides, all students in those three classes also participated in this study.

Instrument of data collection

In conducting this research, primary data were used in a form of transcriptions that were obtained from a video recording. The recording device helped us recording all questions uttered by the teachers during the whole teaching-learning process in the classrooms completely. A manual field note taking was also done during the observation in the classroom as a non-participant observer.

Data Collection Procedure

researchers are non-participant observers during the teaching learning process that means that we did not take any in-class participation to make the classroom run naturally.

The observations were conducted once for each teacher. Each observation took 2 hours as equal as one teaching learning process. Then the recordings were transcribed, only on the teacher question sections. After that, the teacher question transcriptions were gathered with the field note taken on the student responses. We categorized them according to Bloom‟s taxonomy categories for question and responses.

Procedure of Data Analysis Teacher questions

First, after the primary data were obtained on transcription of the teacher questions and students‟ responses, we categorized them into the types of questions categories (Tsui, 1995 as cited by Yang, 2010). Some examples of procedural questions in the data were “Open up your handout at page 4 and read it please?”. Then, some rhetorical questions were “That was tasty, wasn„t it?” were not analyzed. In analysing and calculating the data, symbols: “1)” for yes/no questions, “2)” for closed or display questions and “3)” were used for open or referential questions. Second, using Bloom‟s taxonomy, the teacher questions were categorized again to determine the level of thinking. The categorization of Bloom‟s taxonomy of teacher questions helped me more to decide whether the observed classes have high-level thinking or low-level thinking.

Effects of teacher questions on students’ responses

To analyze the students‟ responses, the lesson transcripts of students‟ responses were analyzed quantitatively. In this case, the average length or the number of words of the students‟ responses on the questions categories were calculated using Yang‟s (2010) method in counting the length of students‟ responses.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Types of Teachers’ Questions in Academic Reading Classes at ED-SWCU Based on a Study Done by Tsui (1995) as cited by Yang (2010)

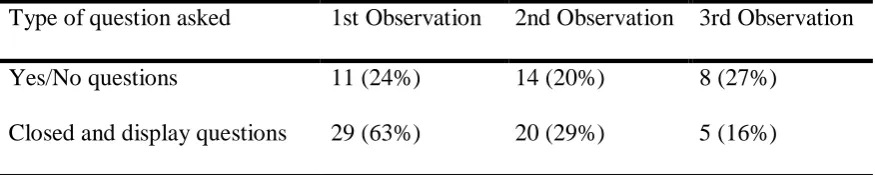

The lesson transcripts of the present study show that in three observations done in the classes, except for the lesson in first observation, open and referential questions were frequently asked. Meanwhile, yes/no questions, and closed and display questions were asked less frequently. Table 1 details the findings.

Table 1. The Types of Questions Used by the Teachers in Each Observation

Type of question asked 1st Observation 2nd Observation 3rd Observation

Yes/No questions

Closed and display questions

11 (24%)

29 (63%)

14 (20%)

20 (29%)

8 (27%)

Open and referential questions 6 (13%) 37 (52%) 17 (57%)

Total no. of questions asked 46 71 30

In the first observation, the type of questions asked most frequently by the teacher was closed and display questions (63%). Mainly, the teachers asked them to check their students understanding about a particular text:

(1) “How big is the Walt Disney influence to the world?” (2) “What is the topic of the second essay?”

The teachers had already known the answer, but they wanted to check their students understanding. There were 29 closed and display questions, followed by 11 yes/no questions and 6 open and referential questions. Some examples of yes/no questions are:

(3) “Have you ever had fruit smoothie?” (4) “Can you see the fruit after mixing?”

(5) “Can you still taste the fruit when it is mixed”

Importantly, questions (3), (4), and (5) possibly trigger students‟ critical thinking that can get them to be more interested in the discussion. For the open and referential questions, they were asked mainly at the beginning of the lesson. For example, the teacher asked open question:

(6) “After looking at the picture, what comes to your mind about synthesizing?”

Here, the open question accepts more than one answer. Question (6) was followed by another question:

(7) “Any other point or thought?”

This incompletely structured question was effective to trigger another different answer from the students and to trigger more participation. Some referential questions related to reasoning were also asked. One example is:

(8) “Why do you make it as fact?”

In the second observation, more than half of questions (37 out of 71 questions) were open and referential questions, which indicated that the students had more chances to deliver their personal thought. From the beginning, open and referential questions (9-12) were asked to make different students came up with their critical thinking even questions.

(9) “What kind of question would we ask?” (10) “Why no why yes?”

Here, the teacher was likely to become a facilitator who helped the students learned by their various opinions. Besides, a simple form of questions asked just after the open, and referential questions were also considered as open and referential questions:

(13) “Any other thought of the overall text whether it is convincing or less convincing?” (14) “Other reason?”

(15) “Any Other?”

Closed and display questions were in the second place with 29% of responses. The questions (16-17) mainly focused on the students‟ knowledge about the journal text that was being discussed.

(16) “What are some other experts who are quoted?” (17) “What are some samples or evidence used?”

Here, the teacher has already known the answer but s/he wants to check whether the students can find any correct information from the journal text or not. The third type, yes/no questions, covered only 14 questions (20%). The questions in this lesson were asked to attract students‟ attention. For example:

(18) “So, let‟s see on the first statistic. Is it convincing or less convincing?”

In that case, the teacher also provided some examples of imaginary cases (see examples 19-20) to grab students‟ attention by the yes/no responses.

(19) “So, for example, let I say that all students in UKSW want to volunteer, but I only interviewed people of FBS. Would that be representative of the whole campus?”

(20) “What if I said that I only interviewed only female students, Would it be representative?”

Finally, in the third observation, open and referential questions were dominant (57%). Contrary, closed and display questions were low, only 5 questions (16%), even lower than yes/no questions that covered 8 questions (27%). Here, just from the beginning of the lesson, the teacher asked open and referential questions as a discussion opener to check the level of students‟ familiarity with a concept of a topic. Some questions (21-23) that led students to share their opinion or thought were dominant.

(21) “After you read, what comes to your mind?” (22) “Murti, want to share?”

(23) “Why does the writer start the essay with some chained questions?”

The closed and display questions were aimed to draw students‟ attention back to the knowledge of the discussed essay text. For example:

(24) “What does in paragraph 7 tell us about?”

(25) “So, the hypothetical technique is stated in a paragraph?”

(26) “If I say that Fatiah is such a feminine lady because she likes to wear jasmine perfume. Is that stereotyping?”

(27) “Do you believe that Martin is more handsome than Bejo?”

To sum up, in three observed classrooms, open and referential questions were frequently asked. Moreover, open and referential questions were being used as a classroom interaction opener (asked at the beginning of the lessons). Hence, the teachers expected that, from the beginning, opinions or thought from the students would dominate the classroom interaction. Also, such type of questions would make the discussion alive. Then, the rest types of questions; closed and display questions and yes/no questions, were asked to help teachers check their students‟ understanding and getting their attention.

Types of Teachers’ Questions in Academic Reading Classes at ED-SWCU Based on Bloom’s Taxonomy

In the first observations, teacher questions were absolutely in the level of lower-order thinking skill, since the questions were only knowledge, comprehension, and application based (see Table 2).

Table 2. The Number and Percentage of the Types Teacher Question in the First Observation

No. of questions

Lower-order thinking skill High-order thinking skill Knowledge Comprehension Application Analysis Synthesis Evaluation

46 25

54,3%

19 41,3%

2 4,4%

- -

- -

- -

Total 100% 0 %

This finding was quite reasonable since there were only 4 (9%) open and referential questions asked by the teacher. The knowledge and comprehension base mainly could be found in the yes /no questions, closed, and display questions. Therefore, in this observation, students were not critically enough in responding teacher questions.

Table 3. The Number and Percentage of the Types Teacher Question in the Second Observation

No. of questions

Lower-order thinking skill High-order thinking skill Knowledge Comprehension Application Analysis Synthesis Evaluation

71 13

18,3%

16 22,5%

11 15,5%

15 21,2%

- -

16 22,5%

Total 56,3% 43,7%

a high number of evaluation based (22,5%), which was the highest level of thinking skill. Although there was no synthesis based found, the number of analysis and evaluation based could determine that the teacher questions could develop students‟ ability to analyze critically and evaluate the concepts and ideas.

Table 4. The Number and Percentage of the Types of Teacher Question in the Third Observation

No. of questions

Lower-order thinking skill High-order thinking skill Knowledge Comprehension Application Analysis Synthesis Evaluation

30 3

10% 9 30% 6 20% 8 26,7% - - 4 13,3%

Total 60% 40%

The third observation also indicated that the teacher questions were lower-order thinking skill. However, the high-order thinking skill still had a quite big portion (40%). Moreover, the teacher questions in this observation could reach 13,3% of evaluation based which was the highest level of thinking skill.

Effects of teacher questions on students’ responses

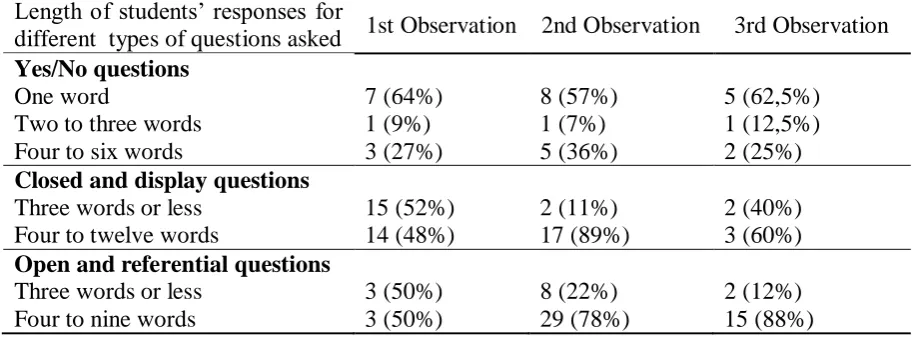

Yang (2010) has shown positive correlation between asking referential questions and students‟ production of the target language. Nevertheless, Yang‟s study states a negative correlation between asking display questions and the length of students‟ responses. The result of the present study shows a similar pattern. The effects of different types of questions asked by the teachers in the Academic Reading classes on the length of students‟ responses are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. The Length of Students‟ Responses for Different Types of Questions Asked in Each Lesson

Length of students‟ responses for

different types of questions asked 1st Observation 2nd Observation 3rd Observation Yes/No questions

One word

Two to three words Four to six words

7 (64%) 1 (9%) 3 (27%) 8 (57%) 1 (7%) 5 (36%) 5 (62,5%) 1 (12,5%) 2 (25%) Closed and display questions

Three words or less Four to twelve words

15 (52%) 14 (48%) 2 (11%) 17 (89%) 2 (40%) 3 (60%) Open and referential questions

Three words or less Four to nine words

3 (50%) 3 (50%) 8 (22%) 29 (78%) 2 (12%) 15 (88%)

words only indicated 3 questions, which students didn‟t answer directly using yes/no. They added some explanations found in the text.

In the second observation, still one-word responses led the numbers although two to three words even four to six words long were quite high. The same as the first observation, the students seemed not to feel satisfied with only yes/no response on yes/no types of questions, they added more explanation. Question 28 shows the teacher‟s yes/no question.

(28)“How If I choose female only, is it representative?”

was followed by the students four to six words response,

(29) “No, because there are not only just females but also males”

Moreover, longer responses with more than six words on the yes/no questions can also be found:

(30) “Does this example help to convince?”

The response was followed by a student‟s long response:

(31) “Less convincing. There is no quantity of the students. So, there is no percentage of how many people in a specific sample. We don‟t know how many people involved.”

Then in the last observation, the yes/no questions still dominantly response with a one-word response. For the other long response, only because the students preferred to give complete grammar answer, such as for the teacher yes/no question,

(32) “If a child has a best friend, and the best friend told the child about „such and such‟, will the child believe to his/her best friend?”

was followed by student‟s response,

(33) “Yes, usually the child will believe.”

The closed and display questions asked by the teachers during their classroom also generally elicited long responses. In the first observation itself, the number of long responses reached 48%. Mainly, the long responses occurred by reading sentences in the text that students thought it as a correct response. Question 34 provides an example.

(34) “What does Kamisar suggest about Euthanasia?”

Then, a student responded the question:

(35) “The active participation of physicians in active euthanasia violates the code of medical ethics.”

short responses were also found in the second and third observations. Question 36 was an example of short responses in third observation.

(36) “So, the hypothetical technique is stated in a paragraph?”

It was followed by a student‟s response:

(37) “Nine.”

When the open and referential questions were asked, the students‟ responses tended to be longer. Moreover, Table 5 showed that the four to nine words responses were higher than the three words or less response in all three observations. Open and referential questions elicited original responses as the product of students‟ critical thinking. One of the examples that I took from the third observation is:

(38) “And why are those comment sections not good enough?”

It was followed by a student‟s response:

(39) “I think it is not clear enoughbecause the writer doesn‟t mention the statistic. So, how can we measure it? And he/she write most but most from what? It is unclear.”

Moreover, there was another student who responded the same question with his/her long answer:

(40) “Because how people commenting in Jakarta post reader forum is are representing people awareness of whole Indonesia, and people have a positive attitude toward English.”

Surely, there is no doubt that the open and referential questions that are dominant in the three observations elicited long and complex critical thinking of students‟ responses.

Based on the analysis of all three observations, students were able to elicit long responses to teachers‟ questions, especially for open and referential questions even they sometimes gave long responses for only yes/no questions. By that finding, It can be interpreted that the students in Academic Reading courses were ready for the more dominant high-order level of thinking, as Table 2 – 4 obviously showed that high-order thinking skill was quite comparable with the lower-order thinking skill.

CONCLUSION

The study concluded that in all the classes, open and referential questions were frequently asked by the teachers, followed by closed and display questions and yes/no questions. Moreover, although low-level cognitive questions were higher than high-level cognitive questions, they did not so contrast like the one stated by previous research. Besides, most of the students in all classes produced long responses.

differently if it is conducted with different subjects. The education background of the subject is the most significance factor that determines the result.

To maintain a balance classroom interaction between the teacher‟s questions and students‟ responses, It is suggested that a teacher has to apply open and referential questions. The long responses indicate that students understand better and have big interests in following the classroom interaction. Also, the other two types of questions still need to be applied to attract students‟ attention on their learning materials.

REFERENCES

Al-Aweiny, B. (2002). Insights into Pencil and Paper English Language Tests and Their Alternatives.Forum, 6. Sultan Qaboos University. Oman.

Anderson, L., &Krathwohl, D.R. (2000). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives, abridged edition (paperback). Allyn& Bacon 2nd Edition.

Beyazkurk, D. &Kesner, J. E. (2005) „Teacher-child relationships in Turkish and United States schools: a cross-cultural study‟, International Education Journal,6, 547–554. Retrieved April 4, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Chi Cheung Ruby, Y. (2010). Teacher Questions in Second Language Classrooms: An Investigation of Three Case Studies. Asian EFL Journal, 12(1), 181-201. Retrieved April 20, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed meth-ods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dobinson, T. (2001). Do Learners Learn From Classroom Interaction and Does the Teacher Have a Role to Play? Language Teaching Research, 5 (3). 189-211. Retrieved April 4, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Hall, J.K. (2002). Methods for teaching foreign languages: Creating a community of learners in the classroom .New Jersey: Merill Prentice Hall.

Hanaas, K. (2009). Decision-making Tasks in Computer-mediated Communication (CMC), in Teaching English with Technology:A Journal for Teachers of English. (1), 1642. Retrieved April 5, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: Teachers perceptions of their interactions with students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16 (8), 811–826. Retrieved April 5, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Ho, D. G. E. (2005). Why do teachers ask the questions they ask? Regional Language Centre Journal, 36(3), 297-310. Retrieved April 4, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Hopper, C.H. (2009). Practicing College Learning Strategies.(5thEd). Cengage Learning, Inc.

Liu, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2010). A Study of Teacher Talk in Interactions in English Classes.Chinese Journal Of Applied Linguistics, 33(2), 76-86. Retrieved April 6, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Moguel, D. (2004) „What does it mean to participate inclass?: integrity and inconsistency in classroominteraction‟, Journal of Classroom Interaction, 39 (1),19–29. Retrieved April 7, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Morse, J. M. (2003). Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral resea rch (pp. 189–208). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nunan, D., & Lamb, C. (1996).The self-directed teacher.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Teddlie, C. (2003). A framework for analyzing data in mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 351–383). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Raymond, E. (2004). Questioning Skills: Asking Questions in the Classroom. On Line Article Retrieved April 6, 2012 from the World http//www.Catb.org/

Tsui, A (1995). Introducing Classroom Interaction. London: Penguin Group

Turner, J.C., and H. Patrick. 2004. Motivational influences on student participation in classroom learning activities. Teachers College Record 106, no. 9: 1759–85. Retrieved April 4, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com

Qu, Y. (2011). The Influence of Communicative Teacher Talk on College Students Interlanguage. Sino-US English Teaching, 8(9), 572-612. Retrieved April 4, 2012 from www.ebscohost.com