Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:43

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Cooperative Goals and Constructive Controversy

for Promoting Innovation in Student Groups in

China

Guoquan Chen & Dean Tjosvold

To cite this article: Guoquan Chen & Dean Tjosvold (2002) Cooperative Goals and Constructive

Controversy for Promoting Innovation in Student Groups in China, Journal of Education for Business, 78:1, 46-50, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599697

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599697

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 84

View related articles

Cooperative Goals and

Constructive Controversy for

Promoting Innovation in

Student Groups in China

GUOQUAN CHEN

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Tsinghua University Beijing, China

s organizations are increasingly

A

calling on teams to promote inno- vation and perform other important tasks, student teams have become inte- gral to business education programs of all kinds. Assigning students to groups may not always be effective. As in work organizations, appropriate conditions must be created for student teams to actually innovate. In this article, we pro- pose that environments where students are able to develop strongly cooperative goals allow them to discuss their con- troversies constructively, and that these open-minded discussions, in turn, pro- mote team innovation and loyalty.Researchers have emphasized the value of teams for innovation and other critical organizational competencies

(Hamel

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Prahalad, 1994; Mohrman,Cohen, & Mohrman, 1995). Researchers have also found that the diversity of per- spectives within a team and open discus- sion of conflicting points of view can facilitate organizational decisionmaking (Cosier, 1978; Eisenhardt, 1989; Sch- weiger, Sandberg, & Rechner, 1989). In this research, we address the usefulness of conflict-oriented teamwork that encompasses diverse viewpoints in the university business classroom. In partic- ular, we investigated the extent to which cooperative teamwork and open contro- versy promote effective student interac- tion and performance. We hypothesized

46

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for BusinessABSTRACT. In this study, the authors used the theory of cooperation and competition to identify conditions that promote student team innovation. Through an investigation of student teams in Beijing, China, the authors found that teams with cooperative goals engaged in open-minded, con- structive controversy, whereas teams with independent goals avoided open discussion. Teams with a high level of

constructive controversy rated them- selves as innovative and loyal.

that cooperative goals help student groups engage in constructive, open- minded controversy that results in effec- tive group work and classroom perfor- mance. Seeking to test the extent to which these ideas, developed in North America, apply to the classroom in East Asia (Hofstede, 1993), we conducted this study in mainland China.

Teamwork for Organizational Effectiveness

Teams are becoming critical, vital methods for organizations to accomplish

central goals. The majority of Fortune

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

500 firms have reported that they use project management, executive manage- ment, and production work teams; only a decade ago, a much smaller minority of firms used these methods (Lawler, Mohrman, & Ledford, 1995). Indeed, teams may be a critical, sustainable com- petitive advantage (Hamel & Prahalad,

DEAN

TJOSVOLD

Lingnan University

Hong Kong, China

1994). Teams are vehicles for combining tacit knowledge for innovation and there- by help the organization prosper in the demanding marketplace (Nonaka, 1990; Simonin, 1999). Groups are vital ways of developing and channeling intellectual conflict between diverse viewpoints into energy that results in new ideas and prod- ucts and effective strategic implementa- tion (Cosier, 1978; Eisenhardt, 1989; Eisenhardt & Bourgeois, 1988; Mason &

Mitroff, 1981; Schweiger, Sandberg, &

Ragan, 1986; Schweiger, Sandberg, &

Rechner, 1989; Schwenk, 1990).

Research on Productive Teamwork

However, teams themselves are not always effective (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Gruenfeld, Mannix, Williams & Neale, 1996). Theory and research indicate that goal interdependence is a useful way of understanding the kind of teamwork that promotes organizational objectives.

The basic premises of the theory of cooperation and competition are that (a) the way that goals are structured deter- mines how individuals interact and (b) the interaction pattern determines the outcomes (Deutsch, 1973; Johnson &

Johnson, 1989). Goals may be struc- tured so that individuals promote the success of others or obstruct the success of others. When a situation is structured

cooperatively, individuals’ goal achieve- ments are positively correlated; individ- uals perceive that they can reach their goals if, and only if, the others also reach their goals. When a situation is structured competitively, individuals’ goal achievements are negatively corre- lated; that is, each individual perceives that when one person achieves his or her goal all the others with whom he or she is competitively linked fail to achieve theirs.

The extent to which team members understand that the relationships among their individual goals are cooperative as opposed to competitive critically affects their expectations, interaction, and out- comes. In cooperation, people believe that as one person moves toward goal attainment, others move toward reach- ing their goals. They understand that others’ goal attainment helps them; they can be successful together. With cooper- ative goals, people want each other to perform effectively, so they interact in ways that promote mutual goals and resolve issues for mutual benefit.

In competitive environments, people, believing that one individual’s success- ful goal attainment makes others less likely to reach their goals, conclude that they are better off when others act inef- fectively. When others are productive, they are less likely to succeed them- selves. They pursue their interests at the expense of others, seeking to “win” and have the other “lose.”

Cooperative goals have been found to lead to constructive controversy, the open-minded discussion of diverse views. Experimental research has docu- mented that people with cooperative goals engage in direct discussions and full exchange of views, which leads to understanding of perspectives and issues (Tjosvold, 1998). Confronted with an opposing view and doubting whether their own position is fully ade- quate, those individuals have been found to be curious and in search of opposing views. They ask questions and demonstrate understanding of the other position. Through defending and under- standing opposing views and reasons, participants begin to integrate ideas to create new, useful solutions. These dynamics lead to quality solutions that participants accept and implement when

they emphasize their cooperative goals. The participants also develop confi- dence in working together in the future. Field studies in the East and West also support the view that cooperative goals foster an open-minded, productive dis-

cussion

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of opposing views that result inquality decisions and implementation

(Alper, Tjosvold,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Law, 1998;Tjosvold & Wang, 1998).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Hypotheses

Because students are likely to work in organizations that are relying more heavily on teams, groups may be impor- tant vehicles for their learning. Thus, in this study we sought to determine how ideas about cooperative goals and con- structive controversy can help in identi- fying effective teamwork in the class- room, particularly as these ideas apply to the collectivist society of China.

We used the research and theory dis- cussed above to formulate our two hypotheses:

H,: Student groups that have coopera- tive goals engage in constructive contro- versy, whereas groups with competitive and independent goals avoid the open-

minded discussion of opposing views.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5:

To the extent that student groups rely on constructive controversy, they are able to innovate and develop team loyalty.We tested these hypotheses in class- rooms in a university in Beijing. Although previous research has focused on differences between the West and the East, we believed that an investigation of how theories developed in one cul- ture are applicable in another would be useful to educators and researchers (Morris, Leung, Ames, & Lickel, 1999). In this study, we tested the universal aspirations of the theory of cooperation and competition.

Method

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Participants

We asked students in learning groups to participate in a study on how they worked together. The groups were an important part of the organizational behavior course in a program for a mas- ter’s in business administration (MBA).

Groups were assigned to make a class presentation and a formal report on a course topic-such as organizational change, organizational structure, cul- ture, cross-functional teams, and lead- ership-for analysis of an actual orga- nization.

Students formed their own groups of six persons or fewer and identified the topic and company by the fourth week. After visiting and interviewing compa- ny managers, they wrote a formal report analyzing the current situation and making recommendations. They gave their presentations in the 16th week of the 18-week course. The group project accounted for 40% of each team member’s final grade. The students completed the survey in about 20 min-

utes at the end of the semester. Only students who volunteered completed the survey. A total of 10 students in two groups did not agree to complete it. One hundred twenty-six students from

32 teams completed the questionnaire;

we used these data in the study. As the hypotheses involved groups, we col- lapsed the responses of team members into one score and analyzed those team level data.

Goal Interdependence

We developed instruments for coop- erative, competitive, and independent goal interdependence from a previous questionnaire study conducted in North America (Alper, Tjosvold, & Law, 1998, see Appendix A). The four coop-

erative goal items measured the empha- sis on mutual goals, shared rewards, and common tasks and had a coefficient alpha of .70. A sample item for the cooperative goal instrument was “The goals of team members go together.” Participants were asked to rate their degree of agreement with five state- ments on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly dis- agree). The competitive goal scale instrument had five items with a coeffi- cient alpha of .75 and with similar anchors for measuring the emphasis on incompatible goals and rewards. A sam- ple item was “Team members’ goals are incompatible with one another.” The independent goal instrument had 6

items with a coefficient alpha of .79. A

September/October 2002

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

47TABLE 1. Correlations Among Variables Within Student Teams

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Constructive

Cooperation Competition Independence Controversy Innovation Team loyalty Cooperative (.70)

Competition -.46* (.75)

Independence -.53* .63* (.79)

Constructive

Innovation .09

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

-.26 -.32 .54* (.93)Team loyalty .48* -.60* -.53** .67* .68* (.76)

controversy .56*

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

-so*

-.71** (.81)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. N = 126. A total of 32 teams participated in the study. Values in parentheses denote reliability (coefficient alpha) estimates. * p < .01.

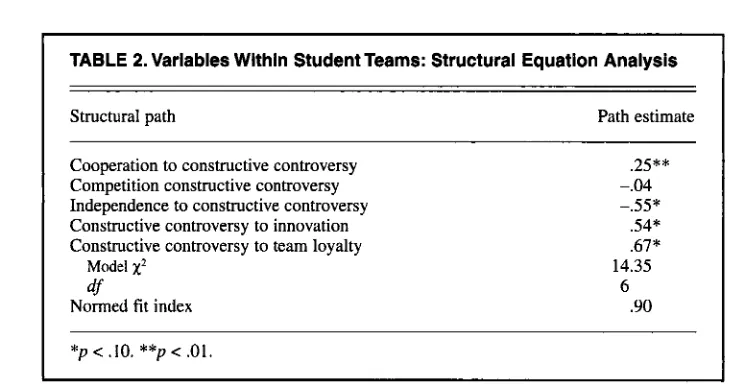

TABLE 2. Variables Within Student Teams: Structural Equation Analysis

Structural path Path estimate Cooperation to constructive controversy

Competition constructive controversy Independence to constructive controversy Constructive controversy to innovation Constructive controversy to team loyalty

Model

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

x2

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

dfNormed fit index

.25**

-.04

-.55*

.54*

.67* 14.35

.90 6

* p < .lo. **p < .01.

sample item was “Team members work for our own independent goals.”

Constructive Controversy

Constructive controversy is the set of behaviors that have been found to devel- op from cooperative goal interdepen- dence in problem-solving situations. People with cooperative, as opposed to competitive, goals have been found to seek a mutually beneficial solution, take each other’s perspectives, directly and

openly discuss their opposing views, and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

try to integrate them for the best solution. We developed the 6-item instrument from a set of experimental studies

(Tjosvold, 1998) and a questionnaire study in North America (Tjosvold, Wed- ley & Field, 1986) that focused on mea- suring the social interaction of team members when the team was engaged in decisionmaking. Subjects were asked to rate their degree of agreement with six statements on a 7-point scale ranging

48 Journal of Education for Business

from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly dis- agree). A sample item was “We use our

opposing views to understand the prob- lem.” The coefficient alpha of the instru- ment was .81.

Innovation and Team Loyalty

Students were asked to rate the inno- vativeness of the team on an 8-item scale developed by Burpitt and Bigo- ness (1997) (see Appendix A). A sample item was “This team identifies and develops skills that can improve its abil- ity to serve existing business needs.” The scale had a Cronbach alpha of .93.

Team members also used a 9-item scale to rate their team loyalty. A sample item was “I feel a strong loyalty to my team members.” The scale had a Cron- bach alpha of .76.

Two research team members who were native Chinese translated the ques- tionnaires, originally written in English, into Chinese. To ensure conceptual con-

sistency, we translated the questionnaires back into English to check for possible deviation (Brislin, 1970). We pretested the questionnaires to make sure that respondents clearly understood every phrase, concept, and question. To prevent and eliminate potential concern for being involved in evaluating others, we assured participants that their responses would be held totally confidential.

Hypotheses Testing

We used correlational analyses as an initial test of the hypotheses. To test the hypotheses more vigorously, we used structural equation analysis with the EQS for Macintosh program to examine the underlying causal structure between goal interdependence, constructive controver- sy, and team innovation and loyalty (Bentler & Wu, 1995). These analyses involved only the structural model, not the measurement model. The research reviewed suggests that constructive con-

[image:4.612.108.473.226.418.2]troversy mediates the relationship between goal interdependence and team innovation and loyalty. We used a nested model test commonly adopted in causal model analysis when comparing the Mediating Effects model with the Direct Effects model. The Direct Effects model posited that goal interdependence influ-

ences team innovation directly.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Results

Zero-order correlations provided an initial examination of the hypotheses linking goal interdependence, construc- tive controversy, and outcomes (see Table 1). Results support the first hypothesis, which states that groups with cooperative goals engage in more constructive controversy and that groups with more competitive and inde- pendent goals have fewer open discus- sions. Our results also support the sec- ond hypothesis, which states that groups that engage in constructive controversy rate themselves as more innovative and as having higher levels of team loyalty. We used sructural equation analyses to explore the relationship between goals, constructive controversy, and out- comes. In Table 2, we show the path estimates for the model tested in this study. Cooperative goals had a margin- ally significant effect on constructive

controversy

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(I3zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= . 25, pzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

< .lo). Compet-itive goals did not have a statistically significant negative effect on construc- tive controversy (13 = -.04, ns), but inde-

pendent goals had a significant negative

effect on constructive controversy (13 = -

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.55,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

p<

.05). With respect to the out-come variables, constructive controver- sy had the expected positive effect on innovation (13 = .54, p < .01) and on team loyalty

(B

= .67, p < .01).In regards to model fit, the model indicating that constructive controversy mediates between goal interdependence and outcomes had a model chi-square of

14.35 with 6 degrees of freedom. The Normed Fit Index for the model was .90, indicating good model fit (Bentler

& Chou, 1987).

Discussion

This study provides assistance to business and other educators who

employ student teams to promote learn- ing. Our results suggest that cooperative, but not competitive or independent, goals provide a foundation for team members to discuss their opposing ideas openly and constructively within the classroom. Our results also support the theory that constructive controversy complements cooperative goals and con- tributes to team innovation and loyalty. To the extent that students developed cooperative goals in their groups, they were able to discuss their opposing views open-mindedly; and teams engag- ing in constructive controversy in turn rated themselves as innovative and loyal. The theory of cooperation and compe- tition, although developed in the West, proved useful for understanding student team dynamics in East Asia. Despite the evidence that Chinese culture stresses harmony and a lack of animosity in rela- tionships, we found the open-minded dis- cussion of opposing views supportive of innovation. Traditionally, researchers have compared samples from different cultures and explored a cultural variable with an indigenous theory (Leung, 1997). This study’s approach of identifying con- ditions that affect group dynamics and outcomes in China and using a theory with universal aspirations may be a viable addition to these traditional approaches.

Limitations

The results of this study are, of course, limited by the sample and oper- ations. The data are self-reported and subject to biases and thus may not accu- rately describe the relationships, although recent research suggests that self-reported data are not as limited as commonly expected (Spector, 1992). These data are also correlational and do not provide direct evidence of causal links between goal interdependence, constructive controversy, and outcomes.

Practical Implications

In addition to developing theoretical understanding, the findings of this research have important practical impli- cations for student learning teams. Our results indicate that the theory of coop- eration and competition is useful for understanding student group dynamics in China. Chinese students responded to

cooperative and competitive goals simi- larly to previously studied samples of students in the West. These results sug- gest that the considerable research and professional practice developed in the West may be useful in making student teams more cooperative and innovative in China as well (Johnson & Johnson, 1999; Johnson & Johnson, 1989; Tjosvold & Tjosvold, 1995, 1994).

Our findings also indicate that con- structive controversy is an important complement to cooperative goals in making student teams innovative and loyal. Students can be oriented and trained in the skills of constructive con- troversy. With these skills, they will express their opposing ideas and posi- tions, ask each other for more informa- tion and arguments, and try to put the best ideas together to create the most innovative solution. In this way, students can make their groups innovative and prepare themselves for working effec- tively in team-oriented organizations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The authors would like to thank Helen Liu for her able assistance and the Hong Kong University Grants Council for its support of this study, grant project No: TDG199LC-3.

REFERENCES

Alper, S., Tjosvold, D., & Law, S. A. (1998). Interdependence and controversy in group deci- sion making: Antecedents to effective self-man- aging teams. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Processes, 74, 33-52. Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained

competitive advantage. Journal of Manage-

ment, 17, 99-120.

Barney, J., Edwards, F, L., & Ringleb, A. H.

(1992). Organizational responses to legal liabil- ity: Employee exposure to hazardous materials. vertical integration, and small firm production.

Academy

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Management Journal, 35,Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological

Methods & Research. 16, 78-1 17.

Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What makes teams work Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23(3), 239-290.

Cohen, S. G., & Ledford, G. E., Jr. (1994). The effectiveness of self-managing teams: A quasi- experiment. Human Relations, 47, 1 3 4 3 . Cosier, R. A. (1978). The effects of three potential

aids for making strategic decisions on predic- tion accuracy. Organizational Behavior and

Human Performance, 22, 295-306.

Deutsch, M. (1980). Fifty years of conflict. In L.

Festinger (Ed.), Retrospections on-social psy-

chology (pp. 4 6 7 7 ) . New York: Oxford Uni- versity Press.

328-349.

September/October 2002 49

Deutsch, M.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(1973).zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The resolutionzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of conJ2ict.New Haven, C T Yale University Press. Deutsch, M. (1949). A theory of cooperation and

competition. Human Relations, 2, 129-152.

Eisenhardt,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

K. M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high velocity environments. Acad-emy of Management Journal, 32, 543-76.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Bourgeois, L. J., III. (1988).

Politics of strategic decision making in high- velocity environments: Toward a midrange the- ory. Academy of Management Journal, 31,

737-770.

Gruenfeld, D. H., Mannix, E. A., Williams, K.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Y., & Neale, M. A. (1996). Group composition anddecision making: How member familiarity and information distribution affect process and per- formance. Organizational Behavior and

Human Decision Process, 67(1), 1-15. Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1994). Competing

for the future: Breakthrough strategies for seiz- ing control of your industry and creating the markets of tomorrow. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in man- agement theories. The Academy of Management Executive, 7, 81-94.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1999). Learning together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning (5‘h ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1989). Cooper- ation and competition: Theory and research.

Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Lawler, E. E.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

111, Mohrman, S. A,, & Ledford, G. E., Jr. (1995). Creating high performance orga-nizations: Practices and results of employee involvement and total quality management in

Fortune

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I000 companies. San Francisco:Jossey-Bass.

Leung, K. (1997). Negotiation and reward alloca- tions across cultures. In P. C. Earley & M. Erez

(Eds.), New perspectives on international

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

industrial/organizational psychology (pp.

640-675). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Mason, R. 0.. & Mitroff, I. I. (1981). Challenging

strategic planning assumptions. New York: Wiley.

Mohrman, S. A., Cohen, S. G . & Mohrman, A. M.

(1995). Designing team-based organizations: New forms for knowledge work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Morris, M. W., Leung, K., Ames, D., & Lickel, B.

(1999). Views from inside and outside: Inte- grating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Academy of Management Review, 24, 781-796.

Nonaka, I. (1990). Redundant, overlapping orga- nization: A Japanese approach to managing the innovation process. California Management

Review, Spring, 27-38.

Parker, G. M. (1994). Cross-functional teams: Working with allies, enemies, and other strangers. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publish- ers.

Schweiger, D. M., Sandberg, W. R., & Ragan, J. W. (1986). Group approaches for improving strategic decision making: A comparative analysis of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy, and consensus. Academy of Management Jour- nal, 29, 51-71.

Schweiger, D. M., Sandberg, W. R., & Rechner, P. L. (1989). Experiential effects of dialectical inquiry, devil’s advocacy, and consensus approaches to strategic decision making. Acad-

emy of Munugement Journal, 32, 745-712.

Schwenk, C. R. (1990). Conflict in organizational

decision making: An exploratory study of its effects in for-profit and not-for-profit organiza- tions. Management Science, 36, 4 3 H 4 8 .

Simonin, B. L. (1999). Transfer of marketing know-how in international strategic alliances: An empirical investigation of the role and antecedents of knowledge ambiguity. Journal

of International Business, 30, 463490.

Spector, P. E. (1992). A consideration of the valid- ity and meaning of self-report measures of job conditions. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 123-15 I). Chichester: Wiley.

Tjosvold, D. (1998). The cooperative and compet- itive goal approach to conflict: Accomplish- ments and challenges. Applied Psychology: An

International Review, 47, 285-313.

Tjosvold, D., & Tjosvold, M. M. (1995). Cooper- ation theory, constructive controversy, and effectiveness: Learning from crises. In R. A. Guzzo & E. Salas (Eds.), Team effectiveness

and decision making in organizations. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 79-1 12.

APPENDIX A

MEASURES FOR VARIABLES WITHIN STUDENT TEAMS Goal Interdependence

Cooperation

together. succeed. er.

er, we usually have common goals.

competition

5. Team members structure things in ways that favor their own goals rather than the goals of other team members.

6. Team members have a “win-lose” rela- tionship.

7. Team members like to show that they

are superior to each other.

8. Team members’ goals are incompatible with one other.

9. Team members give high priority to the things they want to accomplish and low pri- ority to the things other team members want to accomplish.

Independence

10. Each team member does his or her

own thing.

11. Team members like to be successful through their own individual work.

12. Team members work for our own inde-

pendent goals.

13. One team member’s success is unrelat- ed to others’ success.

14. Team members like to obtain their rewards through their own individual work.

15. Team members are most concerned about what they accomplish when working by themselves.

1. Our team members “swim or sink”

2. Our team members want each other to 3. The goals of team members go togeth-

4. When our team members work togeth-

Constructive Controversy

views directly to each other. opinions.

other’s concerns.

1. Team members express their own

2. We listen carefully to each other’s

3. Team members try to understand each

4. We try to use each other’s ideas.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 . Even when we disagree, we communi- 6. We work for decisions we both accept.

7. All views are listened to, even if they

8. We use our opposing views to under- cate respect for each other.

are in the minority. stand the problem.

Team Innovation

1. Using skills we already possess, this team learns new ways to apply those skills to develop new products that can help attract and serve new markets.

2. The team seeks out information about

new markets, products, and technologies from sources outside the organization.

3. This team identifies and develops skills that can improve its ability to serve existing business needs.

4. This team identifies and develops skills to help attract and serve new business needs.

5. This team learns new ways to apply its knowledge of familiar products and techniques to develop new and unusual solutions to familiar, routine problems.

6. This team seeks out information on products and techniques that are new to the operation and learns how to apply them to develop new solutions to routine problems.

7. This team seeks out and acquires

information that may be useful in develop- ing multiple solutions to problems.

8. This team seeks out and acquires

knowledge that may be useful in satisfying needs unforeseen by the client.

Team Loyalty

1. I feel quite confident that my team members will always try to treat me fairly.

2. I have complete faith in the integrity of my team members.

3. I feel a strong loyalty to my team members.

4. My team members would never try to gain an advantage by deceiving each other. 5. I have found that my team members are the kind of persons that keep their promises.

6. At times I am reluctant to trust my team members, because I am suspicious of their motives.

7. I would support my team members in almost any emergency.

8. I have a divided sense of loyalty toward my team members.

9. My team members perform the role of team members the way I would like them to do so.