A Modular Approach to Quality Evaluation of Tourist

Destination Web Sites: The Quality Model Factory

Luisa Mich

aMariangela Franch

bUmberto Martini

ba

Department of Computer and Telecommunication Technology

University of Trento, Italy

b

Department of Computer and Management Sciences

University of Trento, Italy

{luisa.mich; mariangela.franch; umberto.martini}@unitn.it

Abstract

One of the most important steps in Web site quality evaluation projects is the choice of which aspects of the site to consider. The aspects constitute the model of the site itself and should be identified and evaluated based on the objectives of all stakeholders. In some cases it is possible to adopt standard “syntactic” models. Where this is not possible it is necessary to “personalize” the evaluation model so that it takes into account the semantics of the site or sites under assessment. This adaptation takes time and resources. In this paper we put forth a modular approach that supports the definition of detailed semantic models for the evaluation of Web sites of tourist destinations, starting from a common meta-model. The methodology – referred to as “quality model factory” – is based on the identification of unique elements of diverse types of tourist destinations.

Keywords: Web site; quality model; tourist destinations; modular approach; 7Loci.

3

Introduction

Vidgen, 2000) and the 7Loci meta-model – and in particular the standard evaluation table derived from the latter (Mich et al. 2003a).

Yet in some cases it is nonetheless necessary to explicitly state the unique semantic aspects of a site or sites that will undergo evaluation. This is the case with evaluation projects aimed at redesigning or reengineering a site in order to attain higher levels of excellence (Mich et al. 2004); this can be done only by reaching high quality standards: correct site functioning, maintenance and updating, ease of access to the site, and other similar aspects, all necessary to achieve the status of a “high-quality Web site.” That said, merely meeting these standards does not guarantee that a site can be defined as excellent; this requires targeted interventions to “semantic” dimensions of the site, and the presence of services and content that is superior than that generally available from the competition. To this end it becomes necessary to adapt the evaluation model so that it considers the unique semantics of the site under the microscope, a process requiring adequate time and resources.

In this paper we propose a methodology based on a modular approach. Called the “quality model factory,” it starts from the 7Loci meta-model to support the definition of detailed semantic models. We aim to facilitate the definition of a model able to consider with each separate evaluation the realities of diverse tourist destinations without having to make laborious adaptations during the setup phase every time the model is applied to a new site. The unique elements of the different types of destination are identified based on a classification scheme. These elements are used to classify into two modules the aspects of the Web site that will undergo evaluation: the first module groups important features that are common to all tourist destinations; the second groups features for each type of destination. It is thereby possible to have a model that is flexible and exhaustive at the same time, and that can be easily revised to take into account new or previously unidentified aspects that have been deemed important for the quality of a tourist destination Web site. The paper is structured as follows: the next section introduces the classification of tourist destinations used to apply the methodology to these types of Web sites. The third section contains a description of the “quality model factory” and its application for the development of personalized and modular evaluation schemes. The final part summarizes results of these applications, noting specifically the principal theoretical implications regarding the instantiation of models for Web site quality evaluation.

4

Classification of tourist destinations

- a well-defined geographic area with identifiable borders and a territorial identity;

- a tourist offering consisting of attractions and services specifically catering to tourists in the location; the presence of numerous operators with different prospectives and objectives makes it necessary to devise a shared strategy in presenting the offering;

- an understanding of the nature of the potential demand for the tourist products offered;

- awareness of the need to balance tourism’s exploitation of resources with ecological, environmental and community stewardship (Martini, 2002).

-Given its relative newness, the theme of tourist destination classification can still be considered a developing area of study. In our approach we refer to a classification, which dealt with the leisure tourist segment (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of leisure destinations based on their principal attractions

Type of

destination Main reasons for visiting

Well-known examples

Typical attractions found at the destination

Urban Culture, art, architecture,

shopping Capital cities

Nature trails, views, ski trails and slopes, ski-lifts

Rural

Get back to nature, local traditions in agriculture and production

Tuscany, Provence

With this framework it is possible to identify eight distinct types of destination based on the purpose of the vacation and the principal attractions present at the destination. (For another classification, see Buhalis, 2000). The table shows key information about the defining features of a destination. Once established, these aspects can then serve as input when determining the requirements for the Web site of the destination. For example, the images of religious tourist destinations should obviously contain scenes that reflect the primary attraction or activity while the content of the site and services provided at the site should help the user to take advantage of the full offering.

3.

The quality model factory

The main difficulty in devising a quality model lies in clearly identifying the features of the entity under examination, in this case the individual Web site, a difficulty compounded by the specificity of tourist destination Web sites. Therefore, when defining these key characteristics it is necessary to take into account:

- the purpose of the evaluation itself; the model that will be devised must be applicable in comprehensive quality evaluation projects for diverse types of tourist destination Web sites, and it must allow for comparative analyses of positive and negative points of different sites;

- the perspective of all stakeholders; the model must include aspects of quality that are geared toward potential tourists, the owner(s), for the DMO (Destination Management Organization), for local actors and the local population, and also for anyone engaged in the development, maintenance and updating of the site.

A problem-solving approach is best used as a systematic way to define a “personalized” evaluation framework. Specifically, our approach is based on the reuse of artefacts. More widespread in software engineering and especially in programming, the notion of reuse is also helpful in conceptual modelling; it is, in fact, the basis of some of the most recent methods employed in software development (examples being development based on patterns (Fowler, 1997) or components (Heineman and Councill, 2001).

reader to the literature for a more in-depth look at the 7Loci (www.economia.unitn.it/ etourism/pubblicazioni.asp).

3.1 The process of defining the “modular” model

Suppose that we have a class of sites and we want to develop a detailed model to evaluate them. The foundational procedure that serves as the starting point in developing the modular model is outlined in the steps in table 2.

Table 2. Procedure for the quality model factory

{FIRST PART: DEVELOPMENT OF COMMON AND SPECIALIZED MODULES} IF no model for the class of sites currently exists

THEN FOR each of the 7Loci dimensions pertinent to the project

Identify the requirements common to all sites in the class and convert them into a question; then add the question to the Common module in the evaluation model; Identify the specific requirements for the type of site under evaluation and convert them into a question; then add the question to the Specialized module in the evaluation model;

ELSE FOR each dimension of the 7Loci:

FOR each question of the existing model

IF the question is applied to the type of sites in its current form

THEN Add the question to the Common module in the evaluation model

ELSE IF the question requires only a formal modification

THEN Modify the question and add it to the Specialized

module in the evaluation model

IF the question is inapplicable to the type of site under evaluation THEN check whether there is an alternative question and add it to the Specialized module of the evaluation model

{SECOND PART: COMPLETION OF COMMON AND SPECIALIZED MODULES} FOR each requirement for the type of site under evaluation

Identify the 7Loci dimension it refers to

IF no question exists for it in the Common or Specialized module THEN IF the question regards all the sites in the class

THEN Add a question to the Common module

ELSE Add a question to the Specialized module.

sake of simplicity we refer to “questions” to insert in the evaluation modules. In reality this is only one way of formulating the points of the evaluation model; besides interrogatives (usually in Boolean questions) they can also be described in declarative form.

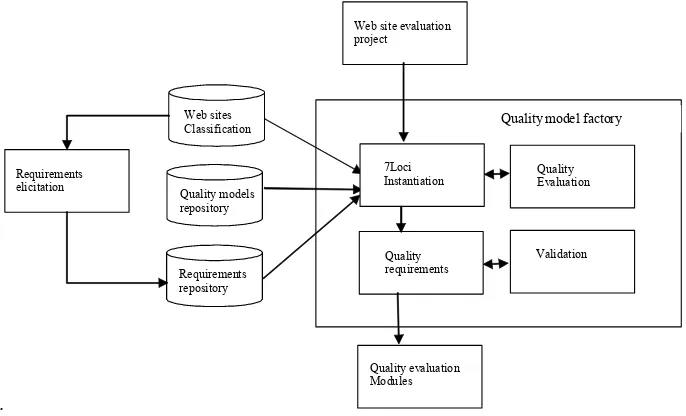

The logic of the structure of the quality model factory is depicted in figure 1, where the necessary input are also shown. Moreover, we can see how the evaluation modules are the result of a validation procedure that is an integral part of the definition of a quality model.

.

Requirements elicitation

Web sites Classification

Quality models repository

Requirements repository

Web site evaluation project

Quality evaluation Modules

7Loci Instantiation

Quality Evaluation

Quality requirements

Validation Quality model factory

Fig. 1. The Quality Model Factory

3.2 Application of the Quality Model Factory methodology in defining evaluation models for Web sites of tourist destinations

as to result in a framework that was adaptable to the specific type of tourist destination.

In practice, this process, starting from the procedure described in Table 2, involved the following activities:

- The decision of which characteristics to consider in the model. Starting with the7Loci meta-model used as a reference framework, it was decided not to include the dimension Feasibility because it includes aspects that can determine the success of the Web site that are at a different level from other characteristics.

- Substitution of the title RTB and other such specific references with the more generic “entity/organisation representing the destination” or “destination.”

- Notation of indications about the use of software tools that enable to automate the answer to specific questions, in particular those regarding Location, Maintenance, and Usability. Also studied were the references to hardware and software configurations to use in the evaluation, as well as threshold values (for example, the maximum percentage of broken links admitted, maximum download time allowed, etc.). These are not merely general assumptions but rather are precise indications coming from ad hoc studies (for example, the database compiled on the maximum download time accepted by users, information gathered on hardware and software configurations most often preferred by users, etc.).

- Some questions containing specific references to the Alpine reality but that also had a wider application were made more general, introducing the possibility to personalize the type of destination and the examples used to define it. Within the questions, the elements that can be specialized are included within brackets < > which indicate the possibility to choose from among a limited number of options. As for the type of destination, there are the eight classes previously listed, while in the other cases this is defined in relation to the unique features of the destination and the environment in which it is considered.

- Revision of the detailed table, specifically of the questions that make up the table. This is done using the output generated in the previous phase of generalization. This made it possible to identify three groups of questions: a) queries that can be applied to the Web site of any type of tourist destination; b) questions that are valid in a general sense but their formulation must be adapted according to the type of destination or a few key characteristics of the destination; c) questions related to specific features of the destination, characteristics of only one type of destination or a subgroup of destinations.

Table 3. Identity questions for rural destinations

Is there a logo/trademark on the home page that identifies the destination (or on the first important page if the home page is secondary, for example, only for language selection)? Is this logo/trademark visible also on other pages of the site?

Is the style of graphic design homogeneous throughout the site?

Does the site contain links to the site of entities or tourist organizations at a higher or lower level, if they exist?

Are external links opened by means of an external window or by means of a frame within the site under evaluation? (Check on the home page or on the first important page if the home page is secondary, for example, only for language selection.)

Are external links encountered while paging through the site coherent with the goals of the entity/organization representing the destination?

Are banners and other advertising (pop ups, links, etc.) present on the site coherent with the goals of the entity/organization representing the destination?

For destinations that belong to more than one category, is it easy to identify the information on the site that is relative only to the type of destination currently under evaluation?

Does the logo/trademark itself somehow inform the user that the site belongs to an entity/organization representing a rural tourist destination?

On the whole, is the graphic design appropriate for the type of site and does it evoke the image of an entity/organization representing a rural tourist destination?

On the whole, is it evident that this is the official site of an entity/organization representing a rural tourist destination?

Is there information or sections/pages dedicated to different market segments (families, elderly, singles, etc.)?

Do the images used bring to mind the idea of a vacation in a rural destination? Is the information provided distinguished by season?

Does the tourist who visits the site come away with an adequate understanding of the type of holiday possible in the region (relaxation, cultural experience, contact with nature, etc.)?

Table 4. Questions per dimension for rural destinations

7Loci Dimension Questions (Total - %Specialized questions)

Identity 15 - 87.5% specialized

Content 26 - 85.7 % specialized

Services 13 - 30% specialized

Location 12 - 0% specialized

Maintenance 8 - 14.3% specialized

Usability 18 - 12.5% specialized

aspects of each type/class, it is possible to use “syntactic” models that are independent of the domain and the specific objectives of the site. In the case of the 7Loci meta-model such aspects are found principally in the dimensions Location, Maintenance and Usability (Deflorian, 2004). A comparison with the model being adopted for the joint project between IFITT (International Federation for IT and Travel & Tourism) and the WTO (World Tourism Organization) aimed at defining a framework to evaluate Web sites of tourist destinations further confirms this duality. On the other hand, the pursuit of excellence presupposes a concept of high quality and differentiation that goes beyond quality performances (already taken for granted by the user). Also for destinations this means intervening on semantic aspects – Content and Services – and on pragmatic aspects, particularly the Identity of the site. It is therefore logical that the greater number of questions deal with the Content and Services dimensions: the first is linked to the information that the site should contain and the second to the variety of target user groups for this type of site.

4

Conclusions

The notion of quality is relative, and this is no less true when talking about Web sites. This helps to explain the numerous methods and models put forth as evaluation tools. Here we have proposed a modular approach that can be used to define evaluation frameworks, calling it the Quality Model Factory. Our goal is to favour reuse at the highest level of the evaluation model. We propose a systemic approach that takes into account the needs of all stakeholders, reducing simultaneously the time and financial investments necessary to define detailed models. The application of the method in evaluating the sites of tourist destinations led to the definition of eight models, which correspond to the eight types of tourist destination in consideration. Experience gained when developing the first detailed model – used to evaluate the sites of Alpine tourist destinations – allowed us to confirm through practical application that the method requires substantially fewer resources. Moreover, by separating the questions for a particular type of site into specialized modules, it was easier to update the evaluation modules. This is particularly important for detailed models, which tend to require frequent modifications. For example, the opening to the Chinese tourist market requires interventions to the site that are primarily cultural and linguistic in nature; the required changes can be more easily and rapidly identified by using an evaluation model that is modular in structure. Future developments of the research could address the comparison of different categories of destinations, which, for example, a national DMO may wish to do within a nation.

References

Barnes, S. J., Vidgen, R. T. (2000). WebQual: An Exploration of Web Site Quality. Proc. of the 8th European Conf. on Information Systems, Vienna, July 3-5.

Browne G.J., Rogich, M. (2001). An empirical investigation of user requirements elicitation:

comparing the effectiveness of prompting techniques. Journal or Management

Information Systems. M.E. Sharpe Inc. 17(4): 223-249.

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future, Tourism Management

Deflorian, E. (2004). Guidelines for Excellence in the Web Sites of Alpine Tourist Destinations.

Degree Thesis. University of Trento, Faculty of Economics. In Italian.

Fowler, M. (1997). Analysis Patterns: Reusable Object Models. Addison-Wesley, 1997.

Heineman, G.T., Councill W.T. (2001). Component Based Software Engineering: Putting the

Pieces Together. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co.

ISO/IEC 9126 (1991). SW product evaluation - Quality characteristics and guidelines for their use; ISO/IEC 9126-1 (2001). SW engineering - Product quality - Part 1: Quality model

Martini, U. (2002) Hypothesis of Destination management in Alpine tourism. In Franch, M. (Ed.), Destination management: Managing tourism from local to global. (pp. 67-111). Turin: Giappichelli. In Italian.

Menapace, M. (2003). Evaluting the Quality of Tourism Destination Web sites: A modular

Approach based on the 7Loci Meta-model. Degree Thesis. University of Trento, Faculty of Economics. In Italian.

Mich, L., Franch, M., Gaio, L. (2003). Evaluating and Designing the Quality of Web Sites.

IEEE Multimedia 10(1): 34-43.

Mich, L., Franch, M., Novi Inverardi, P., Marzani, P. (2003a). Choosing the "rightweight" model for Web site quality evaluation. Springer Verlag, LNCS 2722: 334-337.

Mich, L., Franch, M., Marzani, P. (2004). Guidelines for Excellence in the Web Sites of Tourist Destinations: A Study of the Regional Tourist Boards in the Alps. Int. Conf. e-Society 2004, Avila, Spain, 16-19 July.

Mich, L., Franch, M., Cilione, G., Marzani, P. (2003). Tourist Destinations and the Quality of Web Sites: a Study of Regional Tourist Boards in the Alps. CDRom ENTER 2003.

Olsina, L., Rossi, G. (2002). Measuring Web Application Quality with WebQEM. IEEE