Morten Jakobsen is assistant professor in the Department of Political Science and Government at Aarhus University. His research interests include coproduction of public services, the relationship between public administration and citizens, public employees, information and communication in bureaucracy, and various forms of politi-cal participation.

E-mail: [email protected]

Simon Calmar Andersen is associate professor in the Department of Political Science and Government at Aarhus University. His research examines different aspects of political institutions, as well as budgeting and management strategies and their impact on organizational performance, especially within education. He has published work in Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, and Public Administration, among other journals.

E-mail: [email protected]

Public Administration Review, Vol. 73, Iss. 5, pp. 704–713. © 2013 by The American Society for Public Administration. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12094.

Morten Jakobsen Simon Calmar Andersen

Aarhus University, Denmark

Public managers and researchers devote much attention to the benefi ts of coproduction, or the mixing of the produc-tive eff orts of public employees and citizens in public service design and delivery. One concern, however, is the distributional consequences of coproduction. Th is article proposes that disadvantaged citizens may be constrained by a lack of knowledge or other resources necessary to contrib-ute to and benefi t from the coproduction process. From this assumption, the authors develop the theoretical argument that if coproduction programs were designed to lift con-straints on disadvantaged citizens, they might increase both effi ciency and equity. Th is claim is

tested using a fi eld experiment on educational services. A coproduc-tion program providing immigrant parents with knowledge and mate-rials useful to their children’s early educational development had a substantial positive impact on the educational outcomes of disadvan-taged children, thereby diminish-ing inequity. Economically, the program was more effi cient than later compensation of low-perform-ing children.

O

ver the last decade, coproduction in public service delivery has become a major theme among public managers and public admin-istration researchers. In particular, interest in citizen input to the provision of public services has been growing —and for good reason. Most public services are not just delivered to users who passively receive them. In most public service delivery, citizens, in the form of service users or volunteers, play an active role in the provision process (that is, they “coproduce” the service) (see, e.g., Alford 2009; Bovaird 2007; Brandsen and Pestoff 2006; Osborne 2008; Pestoff , Brandsen, and Verschuere 2012). Examples include services such as health, education, waste recycling, and policing (Alford 2009, 1–3). Th us, citizen input to the service provision process is a central part of overall citizen participation in public services, which alsoincludes, for example, citizens’ involvement in deci-sion making and management of services (John 2009; O’Leary, Gerard, and Bingham 2006; Roberts 2004).

Th is article focuses on coproduction and equity in public service delivery specifi cally. Organizing services in a way that utilizes citizen input as an important resource is often associated with benefi ts such as improved service quantity and quality (e.g., Bovaird 2007; Ostrom 1996; Vamstad 2012). However, less is known about the distributional consequences of

governments’ coproduction strategies. Which citizens will experience improved service outcomes because of copro-duction? Does coproduction potentially increase the gap in service outcomes between advantaged and disadvantaged citizens? Or could coproduction programs be designed in ways that support the most disadvan-taged users in increasing their productive eff orts and service outcomes?

Traditionally, citizens with high socioeconomic status (SES) tend to coproduce more than low-SES citizens (Ostrom 1996; Warren, Rosentraub, and Harlow 1984). Th is article develops the theoretcial argu-ment that disadvantaged citizens may be constrained in their contribution to coproduction by a lack of knowledge (about how to coproduce and the impor-tance of their input) and by a lack of materials that facilitate their coproductive eff orts. Under these cir-cumstances, the way in which coproduction increases the quantity and quality of services may actually excacerbate the gap between service outcomes for advantaged and disadvantaged citizens. On this basis, the article proposes the argument that if programs are designed to lift these constraints, coproduction strate-gies may increase both effi ciency and equity in public service delivery.

Coproduction and Equity in Public Service Delivery

Does coproduction potentially

increase the gap in service

outcomes between advantaged

and disadvantaged citizens? Or

could coproduction programs

be designed in ways that

sup-port the most disadvantaged

users in increasing their

Th is claim is tested using a randomized fi eld experiment, providing an empirical examination of a coproduction program and the dis-tribution of service outcomes across diff erent types of coproducing service users. Th e experiment was conducted in cooperation with a local government. It tests the eff ect of a program providing parents with resources such as knowledge and materials relevant for the coproduction of their young (preschool) children’s Danish-language education. Th e experiment includes 284 children and their families, who were randomly assigned to the program or a control group. Administrative data on educational outcomes as well as parent and child characteristics enable the experiment to

examine the distributional consequences of the coproduction strategy. It was found that the coproduction program increased educa-tional outcomes substantially and that the increase was strongest among children from disadvantaged families, thereby diminishing inequity. Economically, the program is more effi cient than providing compensatory classes to low-performing children after the fact.

Th e next section introduces the concept of coproduction, discusses coproduction in relation to equity, and outlines the theoretical argu-ments. Subsequently, the fi eld experiment design and measures are presented. Th e design section is followed by the fi ndings, a discus-sion of the fi ndings, and a concludiscus-sion.

A Renewed Interest in Coproduction

Citizen participation in public service delivery has a long tradition in public administration research, and the literature includes studies on diff erent ways in which citizens contribute to the design and delivery of services. For example, a great number of studies inves-tigate the potential of citizen involvement in decision making and management of public services (see, e.g., Bingham, Nabatchi, and O’Leary 2005; John 2009; O’Leary, Gerard, and Bingham 2006; Roberts 2004). Another stream of research underscores the impor-tance of citizen input through the nonprofi t (or third) sector (see Bingham, Nabatchi, and O’Leary 2005; Osborne 2008).

Th e concept of coproduction has become an important part of the citizen participation literature since it was fi rst applied in connec-tion with public service delivery in the late 1970s and early 1980s (see Brudney and England 1983; Ostrom and Ostrom 1977; Parks et al. 1981). One of the fi rst defi nitions of coproduction was out-lined by Parks et al.: “Coproduction involves a mixing of the pro-ductive eff orts of regular and consumer producers. Th is mixing may occur directly, involving coordinated eff orts in the same production process, or indirectly through independent, yet related eff orts of the regular producers and consumer producers” (1981, 1002). Th e term “regular producers” refers to public employees and “consumer producers” to the service users. Th us, coproduction not only focuses on citizens’ participation through the decision-making or planning stage of public service programs but also captures citizens’ produc-tive eff orts in service delivery. After a period in which less attention was devoted to the concept (from the mid-1980s until around the millenium), interest in coproduction has been growing rapidly among public managers and public administration researchers once again (see, e.g., Alford 2009, 4–9; Bifulco and Ladd 2006; Bovaird 2007; Brandsen and Pestoff 2006; John et al. 2011, 43–65; Joshi

and Moore 2004; Löffl er et al. 2008; Marschall 2004; Osborne 2008; Pestoff 2008; Pestoff , Brandsen, and Verschuere 2012).

Following the early defi nition by Parks et al. (1981), a number of diff erent defi nitions of coproduction have been applied. Some have prefered narrower defi nitions by, for example, restricting coproduc-tion to instances in which the service is produced through regular, long-term relationships between public employees and citizens (Joshi and Moore 2004). Others prefer broader defi nitions. Notably, B ovaird (2007) expands the defi nition by including volunteers

and community members as coproducers. Furthermore, Bovaird (2007) outlines dif-ferent types of coproduction, distingiushing whether citizens contribute input to the plan-ning of services.

In line with Pestoff , Brandsen, and Verschuere (2012, 1), this article uses the general defi ni-tion of coproducni-tion outlined by Parks et al. (1981). Hence, the focus is on service users as coproducers (for discussions of other types of citizen coproducers such as volunteers and how coproduction relates to the third sector, see Alford 2009; Bovaird 2007; Osborne 2008; Pestoff 2012). Furthermore, the article centers on the provi-sion eff orts of service users rather than their input to planning and management.

Coproduction and Equity

Studies of coproduction have generally found that service user input to public service provision holds great potential to improve services. Th e benefi ts include better service quality and quantity (Bovaird 2007; Ostrom 1996; Percy 1984; Pestoff 2006; Vamstad 2012) and greater effi ciency in the provision of services (Brudney 1984; Marschall 2004).

However, the benefi ts of coproduction are not necessarily evenly distributed across service users. High-SES service users tend to copro-duce more than low-SES service users, even though the latter usually have the greatest need for public services. For example, this is the case in coproduction of education (Guryan, Hurst, and Kearney 2008) and safety (Percy 1987). Hence, to the extent that coproduction raises the quantity and quality of services, a heavy reliance on service user coproduction in public service delivery may exacerbate gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged service users (Rosentraub and Sharp 1981; Warren, Rosentraub, and Harlow 1984).

Even if governments are not pursuing coproduction strategies, in many cases, they are not able to avoid the distributional conse-quenses of coproduction. Th is is because service user input is most often an inevitable part of public service delivery. Furthermore, input from public employees and service users is in many cases complementary, in the sense that public employee input is sup-plemented by service user input and vice versa. In that case, output is maximized when it is infl uenced by a combination of the two inputs. For example, a teacher’s input to education is only eff ective if students engage in learning (Alford 2009, 2–3).

Inspired by Parks et al. (1981) and Ostrom (1996), we use sim-ple, two-input production functions to illustrate this. In fi gure 1,

It was found that the

copro-duction program increased

educational outcomes

substan-tially and that the increase was

strongest among children from

disadvantaged families, thereby

the horizontalaxis displays the amount of service user input (S), and the verticalaxis the amount of regular producer input (R). Th e isoquant lines (Q) show quantities of output for diff erent combinations of inputs. If the inputs from public employees and service users are complementary, the isoquant lines

are curved, as illustrated in fi gure 1. If the two inputs are perfect substitutes, the isoquant lines will be straight. Th e optimal mix of inputs depends on the cost of regular producer input compared to citizens’ costs of coproducing.

In fi gure 1, with regular producer input at R1 and service user input S1, the output will be Q1. However, disadvantaged service users who are constrained and thus only deliver input corresponding to S2 will only obtain output Q2, even if regular producer input is still R1. So even when service users are off ered the same public service, inequi-ties may exist because of diff erent service user input to the copro-duction of these services.

Th ere are at least two ways to counteract this. One is to increase regular producer input and target it at disadvantaged service users, who contribute a low amount of input themselves. However, assum-ing complementary inputs and that we are situated on the steep side of the isoquant (which would often be the case for low service user input), moving from Q2 to Q1 requires a relatively high increase in regular producer input. In fi gure 1, that would be an increase from R1 to R2.

Th e second option would be to lift the constraints that prevent serv-ice users from increasing their input from S2 to S1. A coproduction program with that aim, if eff ective, would reduce inequities of serv-ice outcomes by helping disadvantaged servserv-ice users increase their productive eff orts and thereby increase their outcomes. Th is may also be a more economically effi cient strategy compared to directly increasing regular producer input (i.e., increasing R in fi gure 1). From the perspective of the public sector budget (or a nonprofi t organization that fi nances the coproduction program), this would be the case when the costs of increasing the regular producer input are high relative to the costs of the coproduction program. From a

societal perspective, one should compare the costs of increasing pub-lic sector input with the costs of the program and the costs imposed on service users by their increase in input.

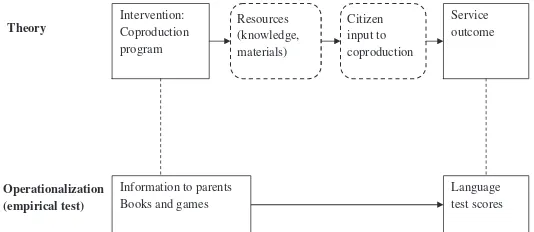

Th e question, then, is how to design a program that counteracts the inequities that may arise from coproduction processes. Figure 2

illustrates this article’s discussion of that question. Th e upper part of fi gure 2 dis-plays the theoretical model, including the assumed causal eff ects. Th e lower part displays the operationalization and empirical test (addressed in the next section).

Th eoretically, the starting point is the eff ect of service user input on outcomes: the fundamental idea in coproduction is that the produc-tive eff orts of service users have an eff ect on the outcome of services (Parks et al. 1981). Th is is illustrated by the causal arrow between service user input to coproduction and service outcome in fi gure 2. In relation to service outcome, the general assumption is made that service users prefer an increased and better service outcome over a diminished service outcome.

Second, it is assumed that the level of service user input to copro-duction is dependent on, among other things, the knowledge and other resources of the service users (see fi gure 2). Th ere are several reasons for this. Some types of coproductive eff orts require service users to have certain knowledge on how to coproduce. For instance, a patient may do physical training after surgery to recover faster and better. Yet if the patient does not know the right exercises and how to perform them, he or she is not able to eff ectively coproduce. Furthermore, the eff ort that service users are willing to invest in coproduction is likely to depend on the benefi t they expect from that eff ort. For example, the better the patient’s understanding of how to contribute to the recovery process—and the better his or her understanding of the relevance of self-contribution—the more the patient is willing to provide a high level of input. Additionally, many kinds of coproduction are more eff ective if service users have specifi c, tangible resources. For example, a patient may need specifi c training instruments in order to coproduce eff ectively and obtain the best possible outcome. (Similar points about the importance of abilities to coproduce have been made by Alford 2002; Percy 1984; Rosentraub and Sharp 1981.)

Empirical studies have found that low-SES service users coproduce less than high-SES service users (see, e.g., Guryan, Hurst, and Kearney 2008; Percy 1987). Th is can hardly be explained by lack

Regular producer input

S1

S2

R2

Q1

Service user input Q2 R1

Figure 1 Mix of Regular Producer and Service User Input

Intervention: Coproduction program

Resources (knowledge, materials)

Citizen input to coproduction

Service outcome

Language test scores

Operationalization (empirical test)

Information to parents Books and games

Theory

Figure 2 Theoretical Model and Its Operationalization

Th

e question, then, is how to

design a program that

counter-acts the inequities that may arise

of need. Rather, this is likely partly attributable to a lack of the knowledge and materials needed to make additional coproductive eff orts eff ective. Th e lack of economic resources among low-SES service users reduces their opportunities to buy materials that would help them coproduce their own or their family’s health, education, and so on (Jakobsen 2013; Warren, Rosentraub, and Harlow 1984). Lower levels of education may reduce service users’ understanding of the relationship between their own contributions and ultimate outcomes. Th is variance in service user knowledge and resources and its relationship with service user input (see fi gure 2) is expected to explain much of the inequity in outcomes found empirically.

Th ird, following the foregoing arguments, this article argues that in order to increase equity and service outcomes simultaneously, coproduction programs should aim to lift the constraints on low-SES service users’ input by providing knowledge and materials relevant for their coproduction. Obviously, coproduction strategies that aim to increase and improve service users’ coproductive eff orts depend on the ability of public organizations to eff ect such eff orts. A number of studies outlining various ways to infl uence service users’ coproduction indicate that this is in fact possible. For exam-ple, Marschall (2006) and Ostrom (1996) show that schools’ eff orts to involve parents have a positive eff ect on parents’ input to school services. Other examples can be found in John et al. (2011).

Against this backdrop, a fi eld experiment was conducted to inves-tigate the distributional consequenses of coproduction—and more specifi cally, whether improving both effi ciency and equity in service outcomes is possible through a coproduction program targeted at increasing service user participation in coproduction.

The Field Experiment

Coproduction of education is an illustrative example of the impor-tance of service user input for service outcomes.1 Family input—

especially the early family environment—plays a crucial role in a child’s education (Cunha et al. 2006; Esping-Andersen 2002; Rowe and Goldin-Meadow 2009). Th erefore, parents are important coproducers of their children’s educational outcomes (as are the children themselves), and there are good reasons to consider parents’ coproduction eff orts in educational services as a form of service user input (for discussions of coproduction of education, see Davis and Ostrom 1991; Ostrom 1996).

Education is also a good example of coproduction that features a great diff erence between low- and high-SES service users in terms of the amount and quality of service user input. Existing research shows that low-SES parents spend less time and communicate less with their children than high-SES parents

(Bonke and Esping-Andersen 2011; Guryan, Hurst, and Kearney 2008; Rowe and Goldin-Meadow 2009). Th is diff erence can partly be explained by low-SES families having less knowledge about skill formation (Rowe 2008). Th ey may also be constrained by lack of materials, for example, children’s books. Th us, education is an area in which public organizations might adopt constraint-lifting strategies when employing service user input in service production in order to improve

both educational outcomes and equity. Of course, the resources that a program must provide to enhance service user input must be tailored to each specifi c case.

In collaboration with a local government in Denmark, a fi eld experi-ment was conducted to examine coproduction and equity in rela-tion to educarela-tion. Specifi cally, the experiment focused on publicly provided language support for immigrant preschool children. As illustrated in the lower part of fi gure 2, the coproduction program was operationalized as a suitcase program (described further later), providing parents with information and basic knowledge about second-language development and materials for their coproduction of this skill. Th e program was aimed at reaching disadvantaged par-ticipant families and lifting potential constraints on their coproduc-tion of their children’s language development in order to increase educational outcomes.

Examining the causal eff ect of coproduction programs empirically, and how the eff ect varies for high- and low-SES service users, entails a number of methodological challenges. Th e fi rst issue is the prob-lem of endogeneity. Service users are almost never selected randomly into programs, which produces bias in comparisons of service users who have been exposed to an intervention and those who have not. Second, a government’s decision to initiate such programs is often aff ected by the existing level of coproduction, which produces two-way causation. Additionally, an empirical examination requires a relatively large study population that varies with regard to SES and includes solid measures of the service outcome and SES. To meet these challenges, a randomized fi eld experiment was used, which enables circumvention of the endogeneity problems but also use of fi eld data. Th e next sections describe the coproduction program, the experimental design, and the data.

The Coproduction Program

Th e coproduction program was rather simple. Each family in the program was off ered a suitcase containing various children’s books, games, and a tutorial DVD about language development tech-niques. Even when parents speak very little Danish themselves, they can contribute substantially to their children’s second-language learning by improving their children’s language profi ciency in general (Collier and Th omas 1989). Th e content of the suitcase was developed by experts in second-language learning.

Th e suitcase was introduced to the families in April 2009 by the employees at the child care centers, and the employees used it in their ongoing communication with the families. Th e program did not include investments or strategies aimed at increasing child care

employee input, but it did aim to facilitate a better mixing and linking of employee and service user inputs. Th e program was gener-ally well received by children, parents, and employees.

One possible challenge is that families and child care employees may change their behavior because they know they are being examined (the Hawthorne eff ect). When starting the program, the families were noti-fi ed that the program was conducted by the

Th

us, education is an area in

which public organizations

might adopt constraint-lifting

strategies when employing

service user input in service

production in order to improve

both educational outcomes and

municipality in cooperation with researchers. However, no further emphasis was placed on the research element. Hence, the treat-ment was organized and delivered by the governtreat-ment as a normal government program, which reduces any potential researcher eff ect considerably.

The Experimental Design

Th e families in the study population were randomly assigned to either a treatment group, which was included in the coproduction program, or a control group, which was not exposed to the pro-gram. Th e random assignment prevents selection bias and two-way causation. Furthermore, the study population varied considerably with regard to SES. Th is enabled examination of the equity question by evaluating the program’s eff ect at diff erent levels of SES.

Th e study population consisted of fi ve-year-old children born in 2004, enrolled in public child care, and learning Danish as their second language. In all, 284 children from 61 child care centers were included in the study, most of whom spoke Arabic as their fi rst language.

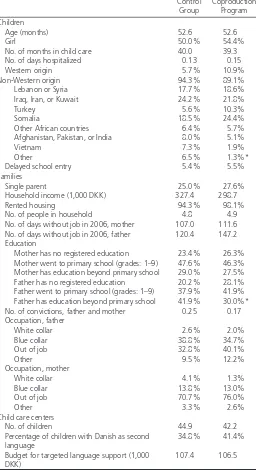

To avoid experimental contamination (the dilution of the treat-ment because control group subjects are exposed to it; see Donner and Klar 2000), a cluster randomization was used to construct the experimental groups. Th e child care centers were organized in clusters of one to fi ve centers. Th e study included 27 such clusters, which were stratifi ed and randomly assigned to either the treatment group or the control group.2 Summary statistics of the experimental

groups are presented in table 1, which shows that the assignment procedure generally resulted in a balanced set of experimental groups. No more signifi cant diff erences are observed than would be expected by chance.

Th e analysis applies the intention-to-treat principle (see Hollis and Campbell 1999). Hence, the children are analyzed in the experi-mental groups in which they were randomly placed, regardless of any shifting between groups, leaving child care before the tests, or use of the suitcase. Th is is done to estimate the eff ect as it occurs in the actual service delivery setting, including all possible implemen-tation issues, and to avoid self-selection bias.

Th e theoretically assumed relationships between parental resources and input to coproduction were not measured (the dotted boxes in fi gure 2). What was tested is the observable implication that if the coproduction program has an eff ect on disadvantaged parents’ input, we should fi nd that the intervention group performs systematically better than the control group—especially among the disadvantaged children. In other words, the diff erence between the control and intervention groups does not express the absolute gain in language development. Parents in the control group also coproduce, and their children experience progress in their language development. Th e diff erence between the treatment and control groups represents the marginal gain in service outcomes produced by the intervention.

Data on Outcomes and Parental Background

Th e service outcome is operationalized by language tests conducted at preschool exit, before the children enter primary school (see fi gure 2). Th is is standard procedure in the municipality. Th us, the study did not introduce any tests for research purposes, which also reduces a potential Hawthorne eff ect. Th e tests are conducted by

language consultants from the elementary school system and not the child care employees who have been providing language instruction, which provides a more objective test measure. Th ree tests are used, each providing a score indicating language profi ciency. Th e children were tested approximately 10 months after the intervention was initiated.

Th e municipality combines the tests into a single categorization that determines the children’s school process. Th is is an important outcome measure: children with critically low language profi ciency are enrolled in special classes before entering the regular school system. Only 2.8 percent of children from the child care pro-grams enter this track (post-treatment statistic). We examined the Table 1 Summary Statistics of Control and Treatment Groups

Control Group

Coproduction Program Children

Age (months) 52.6 52.6

Girl 50.0% 54.4%

No. of months in child care 40.0 39.3

No. of days hospitalized 0.13 0.15

Western origin 5.7% 10.9%

Non-Western origin 94.3% 89.1%

Lebanon or Syria 17.7% 18.6%

Iraq, Iran, or Kuwait 24.2% 21.8%

Turkey 5.6% 10.3%

Somalia 18.5% 24.4%

Other African countries 6.4% 5.7%

Afghanistan, Pakistan, or India 8.0% 5.1%

Vietnam 7.3% 1.9%

Other 6.5% 1.3%*

Delayed school entry 5.4% 5.5%

Families

Single parent 25.0% 27.6%

Household income (1,000 DKK) 327.4 298.7

Rented housing 94.3% 98.1%

No. of people in household 4.8 4.9

No. of days without job in 2006, mother 107.0 111.6

No. of days without job in 2006, father 120.4 147.2

Education

Mother has no registered education 23.4% 26.3%

Mother went to primary school (grades: 1–9) 47.6% 46.3%

Mother has education beyond primary school 29.0% 27.5%

Father has no registered education 20.2% 28.1%

Father went to primary school (grades: 1–9) 37.9% 41.9%

Father has education beyond primary school 41.9% 30.0%*

No. of convictions, father and mother 0.25 0.17

Occupation, father

White collar 2.6% 2.0%

Blue collar 38.8% 34.7%

Out of job 32.8% 40.1%

Other 9.5% 12.2%

Occupation, mother

White collar 4.1% 1.3%

Blue collar 13.8% 13.0%

Out of job 70.7% 76.0%

Other 3.3% 2.6%

Child care centers

No. of children 44.9 42.2

Percentage of children with Danish as second language

34.8% 41.4%

Budget for targeted language support (1,000 DKK)

107.4 106.5

Notes: * p < .05; ** p < .01, two-tailed signifi cance tests of the differences between the control group and the treatment group. Random effects models are used to conduct signifi cance tests.

program eff ects on (1) each of the three tests and (2) the propor-tion of children subsequently enrolled in special classes. Table 2 summarizes the tests.

Th e educational levels of the children’s mothers were used to deter-mine whether the children belonged to an advantaged or disad-vantaged family. Parents’ education is generally a very important predictor of children’s educational chances (Cunha et al. 2006), including among children learning Danish as their second language (Egelund, Nielsen, and Rangvid 2011). Additionally, an analysis was conducted using household income as an alternative indica-tor of SES. Th is produced similar results to the maternal education measurement.

Data on maternal education was obtained through the Danish Civil Registration System and coded as a three-category variable (sum-mary statistics of education are shown in table 1). Th e highest level of education consists of those who have education beyond lower sec-ondary school (i.e., beyond the ninth grade). In the middle category are mothers with a lower secondary education (fi rst to ninth grade). Th e lowest category consists of mothers without registered educa-tion. Mothers in this category have no formal education from the Danish education system, and it was not possible to establish their formal education through surveys of immigrants (every second year, the Civil Registration System surveys immigrants in order to register

their past education). Data on household income were also obtained from the Civil Registration System.

Findings

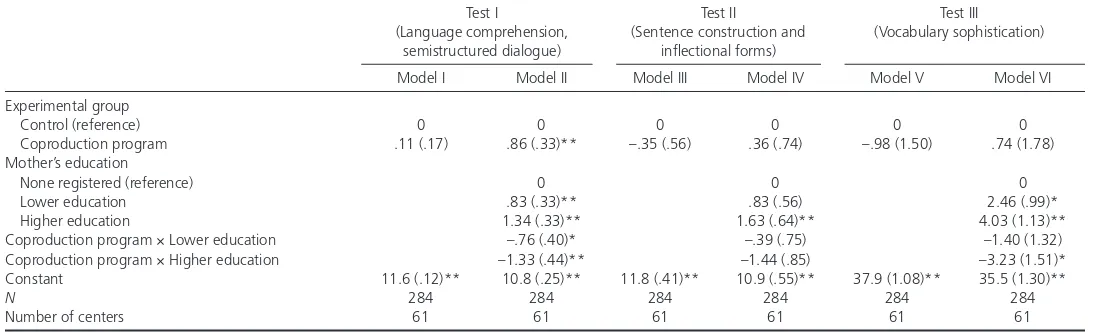

Table 3 shows the eff ect of the coproduction program on the three language tests. All models are estimated by random-eff ects regres-sions using the child care center as the grouping variable (see rec-ommendations of Green and Vavreck 2008). Th e fi rst two models include test I as the dependent variable. Test II is the dependent variable in models III–IV and test III is the dependent variable in models V–IV. Models I, III, and V only include the experimental group as independent variable (1 = treatment, 0 = control) to test the overall eff ects. As models I, III, and V show, the coproduction program has no signifi cant average eff ect on any of the tests.

However, in accordance with the purpose of facilitating coproduc-tion that decreases inequity, the program was primarily designed to reach disadvantaged families. Th erefore, it is likely that the program aff ected this group of families but not the more advantaged families. Hence, models II, IV, and VI examine the eff ect for diff erent levels of maternal education by including interaction terms for the experi-mental group and mother’s education. Th e constitutive term of the experimental group estimates the eff ect of the coproduction pro-gram for families in which the mother has no registered education.

In model II, the program has a statistically signifi cant eff ect of 0.86 (p < .01) for children whose mothers have no registered education.3

Th e overall standard deviation of test I is 1.38, and the treatment eff ect therefore corresponds to about 0.6 standard deviation of the dependent variable. Th is eff ect is substantial in size. Th e eff ect is about as large as the diff erence between having a mother with lower secondary education and a mother with no registered education (this diff erence is 0.83 in the control group). Furthermore, the eff ect is larger than the diff erence between having a mother with higher education levels and a mother with lower education (0.51 for children in the control group). Th e group of children whose mother has no education constitutes one-quarter of the study popula-tion. Hence, the reason that a signifi cant eff ect is observed among low-SES children but not for the entire population is that all of the positive treatment eff ect is located in the low SES-group.

Table 3 Effect of Coproduction Program on Educational Outcomes

Test I

(Language comprehension, semistructured dialogue)

Test II

(Sentence construction and infl ectional forms)

Test III

(Vocabulary sophistication)

Model I Model II Model III Model IV Model V Model VI

Experimental group

Control (reference) 0 0 0 0 0 0

Coproduction program .11 (.17) .86 (.33)** –.35 (.56) .36 (.74) –.98 (1.50) .74 (1.78)

Mother’s education

None registered (reference) 0 0 0

Lower education .83 (.33)** .83 (.56) 2.46 (.99)*

Higher education 1.34 (.33)** 1.63 (.64)** 4.03 (1.13)**

Coproduction program × Lower education –.76 (.40)* –.39 (.75) –1.40 (1.32)

Coproduction program × Higher education –1.33 (.44)** –1.44 (.85) –3.23 (1.51)*

Constant 11.6 (.12)** 10.8 (.25)** 11.8 (.41)** 10.9 (.55)** 37.9 (1.08)** 35.5 (1.30)**

N 284 284 284 284 284 284

Number of centers 61 61 61 61 61 61

Notes: *p < .05, **p < .01. P-values test the one-sided hypothesis. Standard errors are shown in parentheses. Dummy variables on eight twin pairs are included but not shown in the table. Random effects regressions are used to estimate the models (grouping variable: child care center). Dependent variables: Language profi ciency test scores.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of the Individual Language Tests (test score points)

Individual Tests Mean of

Test Score Points

Standard Deviation of Test

Score Points

Observed Test Score Range

N

Test I

(language comprehension, semistructured dialogue)

11.68 1.35 5–13 284

Test II

(sentence construction and infl ectional forms)

11.66 2.62 0–15 284

Test III

(vocabulary sophistication)

37.90 5.12 0–55 284

Th e eff ects of the program on tests II and III (see models IV and VI) are positive for children whose mothers have no registered education, as expected, but not statistically signifi cant. Finding a signifi cant eff ect when examining test I but not when examining tests II and III is not surprising. Th e reason is that the suitcase treatment is, in many regards, aimed at improving language comprehension, which is cap-tured by test I, while other elements are capcap-tured by tests II and III.

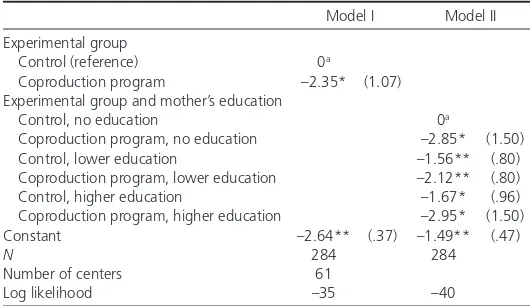

Th e eff ect of the program on the children’s school process was also examined. Th e municipality categorizes the children according to an overall assessment of their language test results, as described earlier. Th is categorization has signifi cant consequences for children’s school process. Children with critically low language profi ciency are enrolled in special classes before entering the regular school system.

Table 4 examines whether the program reduced the proportion of children sent to special classes. Model I examines the average eff ect using a random-eff ects logistic regression. As shown in model I, the coproduction strategy did reduce the group of children enrolled in special classes (p = .01).4 When calculating the predicted

probabili-ties (not shown), the eff ect of the program corresponds to reducing the special class category from 6.7 percent to 0.7 percent, which is a reduction of about 89 percent.

Th e strong treatment eff ect on the proportion of children enrolled in special classes also proves that the coproduction program mainly aff ected children from disadvantaged families, as the risk of being enrolled in special classes is negatively associated with mother’s education. To examine this further, model II in table 4 includes the interaction between the treatment and mother’s education. To avoid interaction terms in the logistic regression, dummy variables are included for the diff erent combinations of mother’s education and the treatment.

Control group children whose mothers have no reported education (no treatment, no education) are used as a reference group. When

this group is compared to the treatment group of children whose mothers have no education (treatment, no education), a treatment eff ect of –2.85 (p = .014) is observed. Th ere are no signifi cant treat-ment eff ects when examining children whose mothers have either lower secondary or higher education (not shown).

In order to provide a more intuitive presentation of the interaction between mother’s education and the treatment, fi gure 3 portrays the eff ect on the proportion of children enrolled in special classes contingent on maternal education. For children whose mothers have no reported education, the treatment substantially reduced the proportion enrolled in special classes (from about 17 percent to 0 percent). For children whose mothers have either lower secondary or higher education, no substantial treatment eff ect is found. In sum, the results show a positive eff ect from the coproduction program on educational outcomes for children from disadvantaged families. Sim ilar results were found in an analysis (not shown) in which household income was used as an indicator of advantaged/disadvan-taged families.

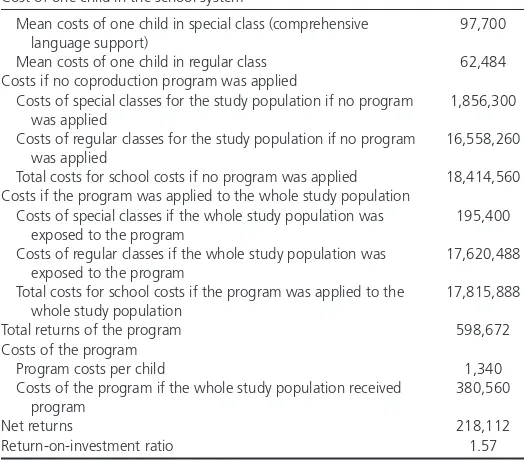

Short-Term Return on Government Investment

Th e coproduction program’s reduction in the proportion of children requiring special classes also entails a reduction in the municipal-ity’s costs of education (which should be contrasted with the costs of the program). Table 5 shows the annual costs (in Danish kroner, DKK) and returns of the coproduction program in a scenario where the program is applied to the whole study population (all 284 children).5 Th e calculation is based on the program eff ects found in

the previous analysis (model I in table 4)—that is, the eff ect on the number of children entering special classes.

Th e mean costs per child in special classes (97,700 DKK) are much higher than the mean costs per child in regular classes (62,484 DKK). Th erefore, from a public sector investment perspective, there are good reasons to ensure that children’s language skills are devel-oped to a level that enables them to enter the regular school system. Th e costs of the program are 1,340 DKK per child (380,560 DKK Table 4 Effect of Coproduction Program on Proportion of Children Sent to

Special Classes

Model I Model II

Experimental group

Control (reference) 0a

Coproduction program –2.35* (1.07)

Experimental group and mother’s education

Control, no education 0a

Coproduction program, no education –2.85* (1.50)

Control, lower education –1.56** (.80)

Coproduction program, lower education –2.12** (.80)

Control, higher education –1.67* (.96)

Coproduction program, higher education –2.95* (1.50)

Constant –2.64** (.37) –1.49** (.47)

N 284 284

Number of centers 61

Log likelihood –35 –40

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01. P-values test the one-sided hypothesis. Standard er-rors are shown in parentheses. Dummy variables for each of eight twin pairs are included but not shown in the table. A random effects logistic regression is used to estimate model I (grouping variable: child care center). The penalized maxi-mum likelihood estimation (Firth 1993) is used in model II to deal with the prob-lem of separation. To avoid interaction terms in the logistic regression in model II, we include dummy variables for the different combinations of SES and treatment groups (there are six combinations, so fi ve dummy variables are included). aReference group.

0 .02 .04 .06 .08 .12 .14 .16 .18

.10 .20

No education registered

(n = 71)

Lower education (n = 133)

Higher education

(n = 80)

Control

group Coproductionprogram Controlgroup Coproductionprogram Controlgroup Coproductionprogram

if the whole study population received the intervention), and the estimated return-on-investment ratio is no less than 1.57.

Th is study did not collect data on the cost of parental input, so the societal cost–benefi t analysis cannot be made. However, long-run cost–benefi t analyses of other child care programs, such as the Perry Preschool Program (see, e.g., Heckman 2006), indicate that there may be substantial long-run gains from the examined program as well. Th e present economic analysis is restricted to the short-run eff ects.

Discussion of the Results

Th e experimental design of the fi eld study avoids the methodo-logical challenges associated with investigating causal eff ects using fi eld data in citizen participation research. Consequently, it can be stated rather confi dently that the coproduction program had a causal eff ect on low-SES children. In the control group, a strong relationship between maternal education and children’s educational achievements was observed (see fi gure 3), which underscores the risk of inequity in services such as education that rely on service user coproduction. Th e coproduction program was able to break that relationship, thereby reducing inequities while effi ciently increasing outcomes.

Th e experimental study design, however, provides less evidence about the external validity of the fi ndings. Th e study was conducted within the area of education and child care in which service user input is known to be of great importance and in which there is great variation between high- and low-SES service users. Th e potential for eff ective coproduction programs may be smaller in other areas in which service user input is less important for outcomes. On the other hand, because most schools and child care centers are already

engaged in parent involvement activities, it may be more diffi cult for new coproduction programs to create a marginal eff ect in educa-tion. In areas in which service user involvement is less pronounced, the potential for eff ective coproduction programs may be greater. Th e theoretical model advanced in this study may provide guide-lines for the design of coproduction programs in other areas that increase both effi ciency and equity, namely, by focusing on the (lack of ) resources that may constrain low-SES service users from coproducing.

Th is article does not contend that direct investments in service users’ coproduction resources, rather than increasing regular producer input, is always the best solution. Th is determination should be based on an evaluation of the specifi c case, and a number of factors should be considered when assessing the generalizability of these results to a given case. When regular producer and service user inputs are complementary and the service user input is low (i.e., a scenario at the steep side of the isoquant in fi gure 1), the likelihood that coproduction programs are the most effi cient strategy increases. Furthermore, the likelihood that coproduction programs are the most effi cient strategy increases when the costs of regular producer input are high relative to the costs of programs aimed at increasing service user input. Additionally, managers should consider whether it is possible to aff ect service users’ coproduction resources and whether managers have suffi cient knowledge about the kinds of resources that should be provided.

Finally, this study does not directly measure parental knowledge and resources or their eff ect on parental time spending. Parents were provided with both information and materials that support their communicative interaction with their children, and it is therefore not possible to separate the eff ect of the two. However, the observ-able outcomes of this study correspond to the empirical implications of the theoretical model, which lends support to the notion that knowledge and material resources are important constraints on low-SES service users’ coproductive eff orts.

Conclusion

Despite the recently revived interest in service user coproduction in public service delivery, less attention has been devoted to the potential trade-off between governments’ reliance on it and equity in service outcomes. Th is arises because disadvantaged service users tend to coproduce less—partly because of resource constraints— than advantaged service users. To the extent that service user copro-duction increases the quantity and quality of service, making service user coproduction an important part of public service delivery may increase inequity in service outcomes. For example, with respect to education, recent research on parental investments in children’s education demonstrates large diff erences between parents with high versus low SES.

Th e identifi cation of such a potential trade-off should give rise to interest in the equity issue as it relates to research on coproduction and to citizen participation in public service delivery in general. Most of the recent wave of research on coproduction has focused primarily on the potential of harnessing citizens’ coproductive eff orts. Less attention has been paid to the potential eff ects (both positive and negative) on equity that may result from an increased focus on coproduction.

Table 5 Annual Short-Term Return-on-Investment Ratio

Cost of one child in the school system

Mean costs of one child in special class (comprehensive language support)

97,700

Mean costs of one child in regular class 62,484

Costs if no coproduction program was applied

Costs of special classes for the study population if no program was applied

1,856,300

Costs of regular classes for the study population if no program was applied

16,558,260

Total costs for school costs if no program was applied 18,414,560 Costs if the program was applied to the whole study population

Costs of special classes if the whole study population was exposed to the program

195,400

Costs of regular classes if the whole study population was exposed to the program

17,620,488

Total costs for school costs if the program was applied to the whole study population

17,815,888

Total returns of the program 598,672

Costs of the program

Program costs per child 1,340

Costs of the program if the whole study population received program

380,560

Net returns 218,112

Return-on-investment ratio 1.57

Th is study contributes a theoretical understanding of how copro-duction of public services—in spite of the potential trade-off mentioned earlier—could instead increase equity. Based on the argument that disadvantaged service users’ input to the coproduc-tion of services may be constrained by lack of knowledge and other resources needed to coproduce, this article argues that if coproduc-tion programs are designed to lift such constraints, coproduccoproduc-tion strategies may increase both effi ciency and equity in public service delivery.

Th e fi eld experiment presented here supports this claim. Th e pro-gram was aimed at lifting knowledge and resource constraints faced by disadvantaged families. Th e results show

that the program signifi cantly reduced the group of children enrolled in special classes by no less than 89 percent, with the largest eff ects found among children from low-SES families. In other words, the inequities in educational outcomes were reduced. By reducing the costs devoted to special classes, the strategy has an immediate return-to-investment ratio of about 1.57. Hence, from a public sector perspective, the program is more

effi cient than providing remedial or compensatory services for low-performing children after the fact.

Th ese fi ndings have several implications for the literature on citizen participation in service delivery and on coproduction in particu-lar. First, they underscore the importance of the equity issue. In the control group, maternal education is highly predictive of child educational achievements, even though all children were off ered the same level of public child care service.

Second, the results clearly show that a coproduction program specifi cally targeted at lifting constraints in terms of knowledge and tangible resources eff ectively benefi ts the most disadvantaged group of children. Th e results show that a coproduction program can

improve equity in service delivery while, at the same time, improv-ing outcomes. As discussed, however, the extent to which these results can be generalized to other service areas or other countries cannot be determined from these data.

Th ird, while not directly tested in the study, the fi ndings also lend support to the theoretical model of coproduction presented—that is, the notion that knowledge and resources are important con-straints on service user input to the production of public services. Th is opens the door for a more nuanced understanding of the coproduction processes that generate inequity. In particular, atten-tion should be devoted to understanding the kinds of constraints that prevent disadvantaged service users from coproducing. Th is study assumed that both knowledge and resources were important constraints but did not determine which of those is more important. Another concern is whether the same kinds of constraints will be relevant in other areas, such as health or elderly care, or whether coproduction programs in these areas should aim at lifting other kinds of constraints.

Th e practical implication of the study is that reducing inequities in coproduction programs does not necessarily require extra public

resources. Th is study tested a low-cost program providing parents with information and basic materials, and it had a great impact on the most disadvantaged group of children and a high immediate return-to-investment ratio.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Aarhus municipality, especially Catharina Damsgaard and Anette D. Knudsen, for excellent collaboration on this project. We are also grateful to Søren Serritzlew for his numer-ous comments and suggestions. Furthermore, the project has ben-efi ted signifi cantly from comments provided by participants of the European Group for Public Administration Study Group on Public

Governance of Societal Sectors (Toulouse, France, 2010), the Public Management Research Association Conference (Syracuse University, 2011), the European Consortium for Political Research Workshop on Citizens and Public Service Performance, and col-leagues at the Department of Political Science and Government, Aarhus University. We also thank Dr. Michael McGuire and three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. Finally, we would like to thank the Danish Institute for Local and Regional Government Research for funding this project’s data collection.

Notes

1. Th e production functions commonly used in education research fi t very well with the subdivision of input to public sector and citizen inputs (see Hanushek 2008).

2. Stratifi cation variables: (1) the children’s statistically predicted language profi -ciency at school start, (2) the child care employees’ attitudes toward language support, and (3) the centers’ share of immigrant children.

3. Robustness analyses show results similar to table 3 if the unbalanced covariates are included in the model or an alternative cluster variable or diff erent estima-tion approaches are used.

4. Robustness analyses confi rm the results.

5. 1 U.S. dollar equaled about 5.2 DKK, and 1 euro equaled about 7.5 DKK at the time of estimation.

References

Alford, John. 2002. Defi ning the Client in the Public Sector: A Social-Exchange Perspective. Public Administration Review 62(3): 337–46.

———. 2009. Engaging Public Sector Clients: From Service-Delivery to Co-Production.

Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bifulco, Robert, and Helen F. Ladd. 2006. Institutional Change and Coproduction of Public Services: Th e Eff ect of Charter Schools on Parental Involvement.

Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 16(4): 553–76.

Bingham, Lisa Blomgren, Tina Nabatchi, and Rosemary O’Leary. 2005. Th e New Governance: Practices and Processes for Stakeholder and Citizen Participation in the Work of Government. Public Administration Review 65(5): 547–58. Bonke, Jens, and Gösta Esping-Andersen. 2011. Family Investments in

Children-Productivities, Preferences, and Parental Child Care. European Sociological Review 27(1): 43–55.

Bovaird, Tony. 2007. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services. Public Administration Review 67(5): 846–60. Brandsen, Taco, and Victor Pestoff . 2006. Co-Production, the Th ird Sector and the

Delivery of Public Services: An Introduction. Public Management Review 8(4): 493–501.

Th

e results show that the

pro-gram signifi cantly reduced the

group of children enrolled in

special classes by no less than 89

percent, with the largest eff ects

found among children from

Brudney, Jeff rey L. 1984. Local Coproduction of Services and the Analysis of Municipal Productivity. Urban Aff airs Review 19(4): 465–84.

Brudney, Jeff rey L., and Robert E. England. 1983. Toward a Defi nition of the Coproduction Concept. Public Administration Review 43(1): 59–65. Collier, Virginia P., and Wayne P. Th omas. 1989. How Quickly Can Immigrants

Become Profi cient in School English? Journal of Educational Issues of Language Minority Students 5: 26–38.

Cunha, Flavio, James J. Heckman, Lance Lochner, and Dimitriy V. Masterov. 2006. Interpreting the Evidence on Life Cycle Skill Formation. In Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by Eric A. Hanushek and Finis Welch, 697–812. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Davis, Gina, and Elinor Ostrom. 1991. A Public Economy Approach to Education: Choice and Co-Production. International Political Science Review 12(4): 313–35. Donner, Allan, and Neil Klar. 2000. Design and Analysis of Cluster Randomization

Trials in Health Research. London: Arnold.

Egelund, Niels, Chantal P. Nielsen, and Beatrice S. Rangvid. 2011. PISA Etnisk 2009—Etniske og danske unges resultater i PISA. Copenhagen, Denmark: AKF. Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 2002. A Child-Centred Social Investment Strategy. In Why

We Need a New Welfare State, edited by Gøsta Esping-Andersen, 26–67. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Firth, David. 1993. Bias Reduction of Maximum Likelihood Estimates. Biometrika

80(1): 27–38.

Green, Donald P., and Lynn Vavreck. 2008. Analysis of Cluster-Randomized Experiments: A Comparison of Alternative Estimation Approaches. Political Analysis 16(2): 138–52.

Guryan, Jonathan, Erik Hurst, and Melissa Kearney. 2008. Parental Education and Parental Time with Children. Journal of Economic Perspectives 22(3): 23–46. Hanushek, Eric A. 2008. Education Production Functions. In Th e New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, vol. 2, edited by Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume, 749–52. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heckman, James J. 2006. Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children. Science 312: 1900–1902.

Hollis, Sally, and Fiona Campbell. 1999. What Is Meant by Intention to Treat Analysis? Survey of Published Randomised Controlled Trials. British Medical Journal 319: 670–74.

Jakobsen, Morten. 2013. Can Government Initiatives Increase Citizen Coproduction? Results of a Randomized Field Experiment. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 23(1): 27–54.

John, Peter. 2009. Can Citizen Governance Redress the Representative Bias of Political Participation? Public Administration Review 69(3): 494–503. John, Peter, Sarah Cotterill, Hanhua Lui, Liz Richardson, Alice Moseley, Hisako

Nomura, Graham Smith, Gary Stoker, and Corinne Wales. 2011. Nudge, Nudge, Th ink, Th ink: Using Experiments to Change Civic Behavior. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Joshi, Anuradha, and Mick Moore. 2004. Institutionalised Co-Production: Unorthodox Public Service Delivery in Challenging Environments. Journal of Development Studies 40(4): 31–49.

Löffl er, Elke, Salvador Parrado, Tony Bovaird, and Gregg Van Ryzin. 2008. “If You Want to Go Fast, Walk Alone. If You Want to Go Far, Walk Together”: Citizens and the Co-Production of Public Services. Report prepared for French Ministry of Budget, Public Finance, and Public Services.

Marschall, Melissa J. 2004. Citizen Participation and the Neighborhood Context: A New Look at the Coproduction of Local Public Goods. Political Research Quarterly 57(2): 231–44.

———. 2006. Parent Involvement and Educational Outcomes for Latino Students.

Review of Policy Research 23(5): 1053–76.

O’Leary, Rosemary, Catherine Gerard, and Lisa Blomgren Bingham. 2006. Introduction to the Symposium on Collaborative Public Management. Special issue, Public Administration Review 66: 6–9.

Osborne, Stephen P. 2008. Th e Th ird Sector in Europe: Continuity and Change.

London: Routledge.

Ostrom, Ellinor. 1996. Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development. World Development 24(6): 1073–87.

Ostrom, Vincent, and Elinor Ostrom. 1977. Public Goods and Public Choices. In

Alternatives for Delivering Public Services: Toward Improved Performance, edited by E. S. Savas, 7–49. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Parks, Roger B., Paula C. Baker, Larry L. Kiser, Ronald J. Oakerson, Ellinor Ostrom, Vincent Ostrom, Stephen L. Percy, Martha B. Vandivort, Gordon P. Whitaker, and Rick K. Wilson. 1981. Consumers As Co-Producers of Public-Services— Some Economic and Institutional Considerations. Policy Studies Journal 9(7): 1001–11.

Percy, Stephen L. 1984. Citizen Participation in the Coproduction of Urban Services.

Urban Aff airs Review 19(4): 431–46.

———. 1987. Citizen Involvement in Coproducing Safety and Security in the Community. Public Productivity Review 10(4): 83–93.

Pestoff , Victor. 2006. Citizens and Co-Production of Welfare Services: Childcare in Eight European Countries. Public Management Review 8(4): 503–19. ———. 2008. A Democratic Architecture for the Welfare State: Promoting Citizen

Participation, the Th ird Sector and Co-Production. New York: Routledge. ———. 2012. Co-Production and Th ird Sector Social Services in Europe: Some

Crucial Conceptual Issues. In New Public Governance, the Th ird Sector, and Co-Production, edited by Victor Pestoff , Taco Brandsen, and Bram Verschuere, 13–34. New York: Routledge.

Pestoff , Victor, Taco Brandsen, and Bram Verschuere, eds. 2012. New Public Governance, the Th ird Sector, and Co-Production. New York: Routledge. Roberts, Nancy C. 2004. Public Deliberation in an Age of Direct Citizen

Participation. American Review of Public Administration 34(4): 315–53. Rosentraub, Mark S., and Elaine B. Sharp. 1981. Consumers as Producers of Social

Services: Coproduction and the Level of Social Services. Southern Review of Public Administration 4(4): 502–39.

Rowe, Meredith L. 2008. Child-Directed Speech: Relation to Socioeconomic Status, Knowledge of Child Development and Child Vocabulary Skill. Journal of Child Language 35(1): 185–205.

Rowe, Meredith L., and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2009. Diff erences in Early Gesture Explain SES Disparities in Child Vocabulary Size at School Entry. Science 323: 951–53.

Vamstad, Johan. 2012. Co-Production and Service Quality: A New Perspective for the Swedish Welfare State. In New Public Governance, the Th ird Sector, and Co-Production, edited by Victor Pestoff , Taco Brandsen, and Bram Verschuere, 297–316. New York: Routledge.