Urban Regeneration for

Istanbul’s Golden Horn

Research Report based on the International

Summer School 2006 at Beykent University

S. Lenferink

J. Lingbeek

Groningen, December 2006 J.P. van Loon

Faculty of Spatial Sciences University of Groningen P.O. Box 800

Abstract

This report is the result of a research performed in project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn. The project areas are Galata Tower, Perşembe Pazari, and Eminönü. The study takes a first step in performing a comprehensive analysis for the three project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn. This is done by using the theoretical framework of the planning triangle that defines three major components within the field of urban planning, namely object, context, and process. The purpose of this study is to show how a sound analysis should be shaped, if the urban regeneration process is to be executed successfully. By doing this, opportunities for urban regeneration are identified.

Although the object description is only part of the analysis that should precede actual urban regeneration, it is the first step towards a thorough analysis of the existing urban environment and the creation of successful projects and plans. This description of the object side of the triangle is performed for the three project areas, leading to the conclusion that the connections between the areas are fairly good, but might be strengthened by making a more efficient use of the waterfronts. The most important improvement needed in the areas is the re-use of vacant and underused land and buildings.

Preface

This research report is the result of a short study in the old city centre of Istanbul. We participated in a workshop called “Two Faces of the Golden Horn” at the Beykent University, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, as part of the International Summer School 2006. The project was supported by the European Union through its Erasmus Youth Program. The workshop consisted of a six-day program, from August 27 till September 2, 2006. The goal of the workshop was to create new plans for several project areas in Istanbul. We did not completely participate in the creation of those new plans, because we thought more research was needed first. Within the limited time we had, we performed part of this research, which is presented in this report.

We would like to thank several persons for their advice, help and dedication to arrange our stay in Istanbul. First of all, this is Tom van der Meulen, for travelling with us, his advice during the week in Istanbul and his comments on this report. We would also like to thank Gert de Roo from Groningen and Altug Ocak from Istanbul for establishing contacts between the two universities and making it possible for us to visit Istanbul for our studies. Then, there are the staff and students of the Beykent Univerity in Istanbul, who worked hard to arrange our stay and guiding us through the city of Istanbul. Last, but not least, our gratitude goes out to the Faculty of Spatial Sciences, University of Groningen for funding our journey to Istanbul. We had a wonderful time in a city that is so different from our cities, but faces a lot of the same problems. It was an instructive experience.

Groningen, October 2006

Contents

Abstract 1

Preface 2

1 Introduction 4

2 The Object: Physical Environment 8

3 The Context: External Influences 12

4 The Process: Urban Regeneration 14

5 Conclusion 18

Description of the Project Areas

6 Project Area One: Galata Tower 21

7 Project Area Two: Perşembe Pazari 26

8 Project Area Three: Eminönü 31

1 Introduction

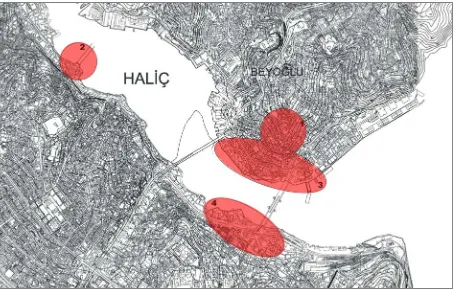

In August 2006, an international summer school was held at the Beykent University, Faculty of Engineering & Architecture. The purpose of this summer school was generating new plans for several project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn, which is a western side-branch of the Bosporus that cuts through Istanbul from North to South. Hence the title ‘Two Faces of the Golden Horn – Re-thinking, Re-generating, Re-using’. During a workshop of six days working groups had been formed and each group had to work on one of three project areas. The project areas are Galata Tower (number one), Perşembe Pazari (three), and Eminönü (four). Figure 1 shows the project areas along the Golden Horn. Project area two was not covered during the workshop.

Figure 1 Overview of the project areas along the Golden Horn of Istanbul. Source: Beykent University, Istanbul.

One of the reasons for organising the workshop is the fact that the project areas are dealing with problems, such as pressure on the available space, the deprivation of buildings, and underused and vacant lots. The lack of space is an issue in many parts of Istanbul, especially the historic parts of the city. In general, there is not much open space in the form of parks and plazas. These parts of the city therefore seem to have reached their limits for housing people. This is not true, however, because open space does exist in the form of underused and vacant lots and deprived buildings (Grava et al., 2002).

with. Important to note here is that urban regeneration as a process is more comprehensive than the urban regeneration described here. This is further explained in chapter 4, which describes the distinction between actual urban regeneration, in the sense of redevelopments, and the process of urban regeneration that includes the analyses, the search for solutions and the decision making process.

Before actual decisions and plans about redevelopment can be made and implemented, research should be performed in order to analyse all elements that influence the specific areas. It is only after a balanced analysis of the areas is obtained that decisions and plans can lead to successful implementation of redevelopment plans. Back in 1915 Patrick Geddes already stated that a comprehensive survey is necessary before drawing up a plan. In The City Reader

(LeGates and Stout (Eds.), 2000) this is still considered as one of the basic principles of modern planning practice.

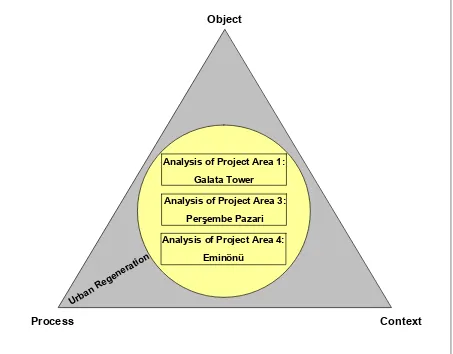

This study takes a first step in performing a comprehensive analysis for the three project areas along Istanbul’s Goden Horn. This is done by using the theoretical framework of the planning triangle (Bertolini and Spit, 1998) that defines three major strands within the field of urban planning, namely object, context, and process. The purpose of this study is showing how a sound analysis should be shaped, if the urban regeneration process is to be executed successfully.

In the remaining of this chapter, we will first clearly state the problem that is at the heart of this study, followed by the objective and research questions. Then, after a concise explanation of the theoretical framework, we move on to the conceptual model that outlines all elements that have been researched and their linkages. The chapter is finished by an overview of the structure of rest of the report.

Problem Definition

In order to make successful urban designs, which is the goal of the Summer School, an analysis of the project areas has to be made. Successful urban regeneration can only be accomplished after a thorough analysis of the project areas. As far as we know, the analysis, which encompasses all the elements of the areas, was not performed for Istanbul’s Golden Horn Region. This means that the characteristics of the area and the external influences on the area are not taken into account sufficiently.

Research Objective

Main Research Question

What are the opportunities for urban regeneration in the three project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn?

Sub Questions

1. What are the characteristics of the three project areas?

2. What are the external influences that have the potential to change the urban environment in the project areas?

Theoretical Framework

The planning triangle (Bertolini and Spit, 1998, p. 3-8) will serve as a theoretical framework in this study. The planning triangle structures the field of an urban land use planner and consists of three components: object, process and context. The object represents the substance of the problem. The process involves actors and their powers in the planning arena and shows the organization of the planning arena. The context defines the limiting conditions of the object and process. These limiting conditions, however, should be interpreted broadly, because they can also be seen as opportunities; certain contextual developments can provide new possibilities for changing the urban environment. One of the three components can be emphasised, depending on the problem and the way the problem is approached. In general, urban land use planners emphasise the object. While this object approach is a major part of this study in order to describe the project areas, an attempt to include the process and context has also been made. The emphasis is placed on the process, once the object and context, without which the process could never take place, are analysed.

Process

Object

Context

The Planning Triangle

Conceptual Model

three project areas in accordance with the planning triangle therefore leads to a comprehensive overview of all factors involved in urban regeneration.

Taking actual urban regeneration, i.e. the rebuilding of certain parts of the urban environment, as the ultimate goal, the object, the context, and the process are all analysed in order to provide insight into some opportunities for this urban regeneration. The concept of urban regeneration is placed in the process corner of the planning triangle, because it functions as a process that guides the field of urban planning, as will become clear in chapter 4. However, urban regeneration needs the object and context to be successful, which is symbolised by the direct linkages between the process on the one hand and the object and context on the other.

Analysis of Project Area 1:

Galata Tower

Analysis of Project Area 3:

Perşembe Pazari

Analysis of Project Area 4:

Eminönü

Object

Process Context

Urba n Reg

ener ation

Figure 2 The conceptual model

Structure of the Report

2

The Object: Galata Tower, Per

ş

embe Pazari,

and Eminönü

The planning triangle, as mentioned earlier, consists of three components: object, process, and context. The object, which represents the substance of the problem, is discussed in this chapter. In this study the object consists of the three project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn. These project areas can be considered as one place, but also as three separate places. The first thing we need to know is what the term place exactly means. In order to describe the term place, the more abstract term space is discussed. Namely, space encompasses place or, in other words, place is just a part of space.

Jenkins (2005) distinguishes absolute and relative space. He argues that absolute space is “abstract and real, existing whether it is filled or not – framing and containing all physical elements” (2005, p.19). Relative space is “space that exists only through definition of the things it contains – i.e. that space is relational” (2005, p.19). According to Knox and Marston (2003) absolute space is a mathematical space. It can be determined through mathematical reasoning, for example through points, lines and planes. Relative space can be either socioeconomic space or cultural space. Socioeconomic space can be determined through measures of time, cost, profit, production, and physical distance. Examples are routes and distribution patterns. Cultural spaces are spaces whose attributes carry special meaning for groups of people with common ties. These spaces can be for example places and territories.

Knox and Marston their descriptions of absolute, relative, and cognitive space point out that place is just a part of space. Namely, place is cultural space, which is relative space. Jenkins (2005) discusses the term space in relation to the term place. He argues that the term space is used to denote physical location, while place relates to physical attributes. Due to the fact that place was described as relative space – space that exists only through definition of the things it contains – and that place relates to physical attributes, we specified a list of physical attributes, together with general characteristics, to describe the three project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn. This list contained the following elements:

• Function of the Area • Infrastructure and Traffic • Heritage and Landmarks • Open and Green Spaces • Use of Waterfront

The three project areas are discussed based on these physical attributes. The attributes can be judged positively or negatively. In order to make a more comprehensive judgment of the project areas we formulated three, more abstract terms, which encompass a number of, or all of the physical attributes. These more abstract terms are:

• Walkability • Connectivity • Liveability

Walkability is the pedestrian-friendliness of an area. The pedestrian system must provide clear, comfortable, and direct access to the core commercial area and transit stop. Walkability is associated with pleasurable urban environments, compact development, and functional mass transit (Steuteville and Langdon, 2003). Connectivity is simply the connection(s) between the physical attributes. It indicates the extent to which areas and attributes contrast to or complement others. Liveability is the quality that humans experience in their daily environment. It relates to all sectors of the built environment and is determined by social, spatial, economic, and environmental qualities (De Roo, 2001).

Cheng et al. (2003, p.90) state that place is “not simply an inert container for biophysical attributes; place is constructed—and continuously reconstructed— through social and political processes that assign meaning”. According to Jenkins (2005, p.20) place is “the predominantly socio-cultural perception and definition of space, and is an important element of social identity – whether individual or collective”. This can be understood by describing how Yi-Fu Tuan and Rose define place. Yi-Fu Tuan (1977, p.6) argues that “what begins as undifferentiated space becomes place as we get to know it better and endow it with value”. He also points out that places are spaces, which serve as “centers of meaning to individuals and to groups” (2004, p.387). Rose (1995, p.88) discusses that a “place is something created by people, both as individuals and in groups”. She argues that “places are significant because they are the focus of personal feelings” (1995, p.88). The arguments of Yi-Fu Tuan and Rose point out that places are filled with meaning and feeling, which are the consequence of social interactions. The meanings that people give to places and the feelings they have about these places can be so strong that these become part of their identity, whether it is an individual sense of identity or group identity. Therefore places serve as an important component for both types of identity. It should be noted that both individual identity and group identity are influenced by social interactions.

The previous paragraph indicates that place and identity are closely related terms. It is not surprising that these two terms have been combined into what is called place identity. Proshansky et al. (2000, p.319-20) define place identity as a “substructure of the self identity of the person consisting of broadly conceived cognition about the physical world in which the individual lives”. Twigger-Ross and Uzzell (2000, p.320) argue that place identity is not only a substructure of identity, but that “all aspects of identity have place related implications”. Rutherford (1995, p.88) states that “identity marks the conjuncture of our past with the social, cultural and economic relations we live within”.

memories that they associate with a place, and to the symbolism that they attach to it”. This definition displays that sense of place is personal; it is based on individual feelings and meanings. However, as discussed in Rose (1995) feelings and meanings are also shaped by social, cultural, and economic relations. Now, when Rutherford’s definition of identity and Knox and Marston’s definition of sense of place are combined this leads to the following definition: place identity marks the conjuncture of the feelings evoked among people as a result of the experiences and memories that they associate with a place, and to the symbolism that they attach to it, with the social, cultural and economic relations we live within.

According to Hague (2005) place identity is attracting increasing interest in planning practice as well as in social science research. An example of Jenkins (2005) about the fact that physical space is registered mentally in so-called mind-maps will clarify why place identity could be interesting for this study. Jenkins uses the example that members of the same household will use different physical attributes to describe the area they live in. Due to different perceptions and activities a person will describe a physical space differently than others would do. Furthermore, people will describe the same physical space in a different way to others and, as time passes by, they will describe that physical space in another way. Therefore, in order to describe the object of this study, not only the physical attributes of the places should be investigated, but also the place identities of these places. However, due to time and language restrictions, we were not able to perform interviews with the people who live in the project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn in order to find out what the place identities of these places are.

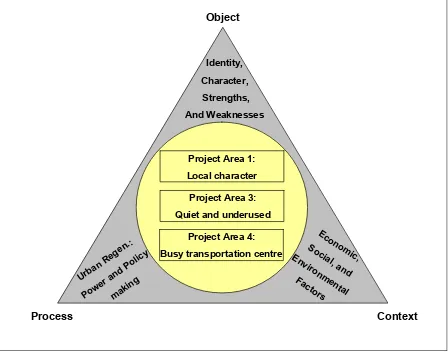

Project Area Description

We will give an overview of the three project areas, which form the object within the planning triangle. This overview is based on the defined physical attributes, the walkability, the connectivity, and the liveability of each area. A detailed description of each project area can be found in part two. We will start with an overview of project area one, Galata Tower. Subsequently, project area three, Perşembe Pazari, and project area four, Eminönü, are described. Finally, the project areas are discussed in relation to each other.

In theory, project area one could attract tourists because of its location, lying between the old part of Istanbul across the Golden Horn, and the new commercial area of Beyoğlu. This is not the case, because the walkability, connectivity and liveability of project area one is poor. This could explain the fact that the area still keeps its local character and does not attract a lot of tourists. It is questionable to what extent the local character forms a problem. The local character could be the charm of project area one. The liveability for example could be poor according to Western standards, but the local Turkish people are used to the conditions, and maybe have lower standards. They can live their lives in the area; happy with the absence of hordes of tourists.

and open spaces make the area contrasting with the busy areas of Beyoğlu and Eminönü. The strength of this area is the quietness, and possible urban regeneration plans, to improve the sights of this area, should take this fact into consideration.

The key elements for project area four are transportation in many forms, shopping and religion. Heritage is directly related to this, because religion is being ‘practised’ in old, remarkable mosques that stand out of their environment and are thus landmarks. The busy character of project area four is not attractive in terms of liveability, but should not be tried to get rid of. In contrast, it can be considered as an opportunity and should be strengthened. This could be done by improving transportation facilities, e.g. a rearrangement of the bus station and the creation of piers for the passenger boats. Another aspect that needs to be altered is the vacant and underused land or buildings. The space that emerges by re-using that land or those building can help solve some of the problems of the area, such as the limited parking opportunities. Urban regeneration should be performed with the busy character of the area in mind. Therefore, technical solutions in terms of physical adjustments and civil engineering will be of most concern at this point in time.

3 The Context: External Influences

In the previous chapter, the object of planning was discussed. To be able to provide a better insight into the external influences, which can change the urban environment in the project areas, the context of the object has to be investigated. According to the American Heritage Dictionary (2006), the context is “the circumstances in which an event occurs”. In our study the context is defined as the emerging topics and themes that can influence the object. It can broadly be divided in three categories: economic, social and environmental factors. This chapter will point out some of the external influences and the possible consequences for the urban environment.

Economic Factors

Economic factors could include economic developments on a higher level of scale, for example regarding the national economy, which subsequently influence the local economy. In recent years the economy of Turkey grew by 7,9; 5,8; and 8,9 percent (OECD Statistics, 2006). This growth has implications for Turkey, and especially for Istanbul. The growing economy could stimulate the demand for houses and office buildings, having the potential of real estate prices in the city rising. This could make the less densely developed and cheaper areas become more attractive for investments. Project area three seems to be a perfect opportunity for real estate agencies to gain profit. The location of the area seems perfect, in between the old, historic centre and the new, commercial centre of Istanbul. Therefore, the location is great and the prices of the buildings are not high. This is illustrated by the high degree of vacant buildings. The low prices and the great location provide developing opportunities for this area, e.g. the project area could be developed into a living area for rich people. The area is less suitable for other, more commercial functions, because these will have a negative influence on the quiet character of the area. Another economic issue which could have major impacts on Istanbul, is Turkey’s entrance to the European Union. The last couple of years Turkey is becoming a serious candidate for admission to the Union. If this would happen, Istanbul’s real estate market could become better accessible for foreign investors. Project area one, the former international quarter of Istanbul, contains old foreign buildings. These buildings could be interesting investments for foreign developers. They could make use of the past of the project area to create a regenerated, international quarter.

Social Factors

This changing role of family changes the number of people living in one house just like the individualisation does. The two combined, subsequently influence the demand and supply of houses, the real estate market, which is a part of the urban environment.

Environmental Factors

The environment is also an emerging source of change. A change in environmental context could be the changing climate. The rise in sea level is just one example of the changing climate. According to the National Research Council (1987, in Nicholls, 1995) the most serious impacts of sea-level rise are:

• an increased risk of flooding and impeded drainage • salinisation of freshwater supplies

• higher water tables which may reduce the safety of foundations • beach erosion

A sea-level rise could have dramatic consequences for the city of Istanbul. Istanbul is surrounded by water. The sea of Marmara, the Bosporus and the Golden Horn are waters which border the city, or are part of it. If the sea-level rise continues, Istanbul will have to face the consequences. Building on land close to the water would become impossible, except when adapting the design to the water. Amphibious houses or floating houses like in Maasbommel (Dura Vermeer, 2006) could proof to be the new way of building in Istanbul.

The context illustrates the diversity of external influences which could affect the object. It is not possible to account for all these influences in the urban regeneration process. However, one should be aware of the impact that the external influences could have, especially their ability to set limitations and provide opportunities. Awareness of the context guarantees an early recognition of the opportunities, providing the decision-makers with time to deal with these adequately.

4 The Process: Urban Regeneration

The ultimate goal of the workshop week in Istanbul was to generate creative solutions for the urban problems of three project areas along the Golden Horn of Istanbul. Although this study will not cover possible solutions for these urban problems, it is useful to discuss the concept of urban regeneration, because it is necessary to think of all aspects of this concept, before actual solutions to urban problems can be provided. Urban regeneration functions as the process over time, as was proposed in our conceptual model. In this chapter the concept of urban regeneration will be explained and discussed.

Urban regeneration is often used to address the rebuilding and redevelopment of urban slums, i.e. deprived, underused, and vacant land and buildings in an urban area. We could call this actual urban regeneration (the term urban renewal is used also), characterised by the action of changing the urban environment. At this point, it is important that the process of urban regeneration is more than merely changing the urban environment. As will become clear in this chapter, the process of urban regeneration is more comprehensive and complex.

The problems in an urban area are caused by the change of cities over time. This change, for example a different economic base (service industries instead of manufacturing) or decentralisation, leads to different needs within the urban area. The problems that result from these changes are for example physical, such as underused or vacant land and abandoned buildings, but also social, such as unemployment and social deprivation. The search for and creation of solutions for these problems is known as urban regeneration, which usually takes the form of public policy in order to regulate urban processes and attempt to improve the urban environment (Couch, Fraser and Percy, 2003, p. xv).

Although this description sounds fairly simple and straightforward, the opposite is true. In order to show how complex urban regeneration is, it is useful to see how Home (1982) describes the concept of inner city regeneration (which is practically the same as urban regeneration): it “involves complex social, economic, environmental and political issues, no profession or academic discipline can claim a monopoly over it. To list them alphabetically (but not to claim completeness), architects, economists, environmentalists, geographers, historians, planners, political scientists, sociologists and surveyors have all contributed to ‘the inner city debate’, which has become increasingly confused and formless” (p. xi).

Urban Regeneration is defined by Roberts (p. 17, in Roberts and Sykes, 2000) in

Urban Regeneration: A Handbook as “comprehensive and integrated vision and action which leads to the resolution of urban problems and which seeks to bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental condition of an area that has been subject to change”. This definition implies that urban regeneration is different from other forms of action that change the urban environment. Below, this difference is further explained.

themes from the past (in chronological order), whereas the sixth theme is the dominant issue of the present and the future. The dominance of the sixth theme does not implicate that other themes are irrelevant for the present and future. Throughout time, all themes have different levels of importance and it is possible that a theme regains attention in the future.

1. Physical conditions and social response: The responses made to the questions of improvement and maintenance of urban areas change over time, depending on the socio-political and economic circumstances.

2. Housing and health: Improvement of living conditions of urban residents by providing pure water, open space, suitable housing, etc.

3. Social welfare and economic progress: The linking of economic prosperity to better social welfare and physical conditions, such as the Garden City Movement tried to achieve with their Garden cities in which the good aspects of town and country were combined (Roberts, p. 13, in Roberts and Sykes, 2000).

4. Containing urban growth: The attempt to restrain urban growth and protect nature from the ever-growing cities by using urban space more efficiently. 5. Changing urban policy: Since the mid-twentieth century urban policy changed

from a central-led activity to a regional or local approach, with a style of consensus politics and more attention for environmental problems.

6. Sustainable development: The last and latest theme of urban regeneration which will influence the future of urban areas. “[Sustainable development is] development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, in: Rosen and Dincer, 2001, p. 8).

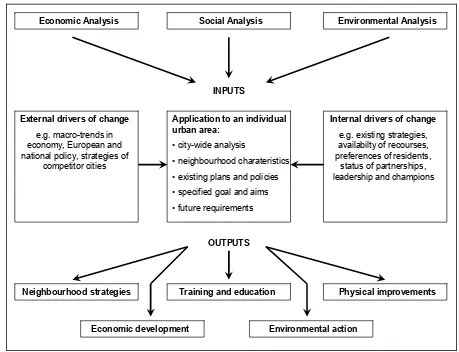

Roberts (in Roberts and Sykes, 2000) provides a list with principles that should be considered when working on urban regeneration. This list goes from the necessity of a detailed analysis and sustainability to ensuring consensus and the constant need of adapting strategies and policies. Figure three, which is taken from Roberts, gives a more detailed overview of all principles related to urban regeneration and their interaction and, in fact, shows how the process part of the planning triangle could look.

Urban Regeneration as a Process

In the broader perspective of the theoretical framework that was proposed in the introduction – the planning triangle – urban regeneration functions as the process; it shapes the system of analysis, problem definition, solution/strategy propositions, decision/policy making, and, eventually, implementation. Decision/policy making is an essential part of the process. It is determined by the input for the process of urban regeneration, which is the current urban environment – the object – and other influencing factors, such as internal and external drivers of change – the context (see figure 3). Also, the output of decisions and policies possibly leads to changes in all elements of the urban environment.

the project areas fall into different districts, the governmental structure is not considered to differ between the districts; they are all part of the governmental structure that is present throughout Turkey (Wikipedia, 2006). We are unfamiliar with the exact structure of the government in Istanbul and the decision/policy making procedures. It was not possible to research this due to the limited time that was available on the one hand and the language restrictions on the other. Nevertheless, government and power should be considered in practising urban regeneration. It is possible that the different governments in the city districts come to different decision, merely because the persons involved in the decision making process are not the same and the problems at hand differ. They might also have trouble with working together and link separate plans together, so that the connections between the areas will be improved.

Neighbourhood strategies Training and education Physical improvements

Economic development Environmental action INPUTS

OUTPUTS

An important lesson that can be learned from this overview is that analysis of the object, context and process, within the urban environment, is essential for urban regeneration. It is only after thorough research has been done that strategies and policies can be shaped in order to successfully change the physical and/or social environment. This corresponds to one of the basic principles of modern planning practice, as Geddes (1915) had already stated: “survey before plan”.

5 Conclusion

One of the ways to improve spatial quality in urban areas is through urban regeneration. Urban regeneration can be defined as comprehensive and integrated vision and action which leads to the resolution of urban problems and which seeks to bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental condition of an area that has been subject to change. To be able to apply urban regeneration in an effective way, the characteristics of an area need to be taken into account together with the external influences on the area. The need for thorough analysis of the existing urban environment and the external influences, as an essential step in the urban regeneration process, resulted in the following research question:

What are the opportunities for urban regeneration in the three project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn?

In order to structure the field of the urban planning process and thus the scope of this study, the framework of the planning triangle was used. This framework consists of three components: object, process and context. Each component was used to describe part of the forces that could influence the physical environment of the project areas. The actual analysis that was performed focused on the object descriptions of the areas, of which the most striking characteristics are described below.

Project area one, the area around the Galata Tower, is characterised by its small, steep streets. These steep streets constrain the development of the area. Tourists skip the area, because of the poor walkability and connectivity. But the resulting local character could be the charm of the area. Urban regeneration could focus on keeping the local character intact but improving the liveability for the Turkish people that have their homes in this area.

Project area three, Perşembre Pazari, is isolated from the surrounding areas by means of an arterial road and two bridges. This isolation guarantees the quietness of the area, and keeps the walkability at a high level. There are a lot of possibilities to improve the liveability, for example by regenerating the abandoned and derelict buildings. The regeneration should take into account that the area keeps its local character, contrasting with the busy areas of Beyoğlu and Eminönü.

Project area four, Eminönü, functions as a transportation, shopping and religious centre. Liveability is not a primary concern, because not many live in the area. Traffic congestion is a major problem in the area, a problem which affects the liveability, connectivity, and walkability. Therefore, civil engineering in order to solve the congestion problem seems to be the primary concern.

Historicity and modernity go together well in each area and the connections between the areas are fairly good, but might be strengthened by making a more efficient use of the waterfronts.

Besides the current situation in the three project areas, there are several contextual factors that have the potential to influence this environment in the future. This was argued in the description of the external influences (context), in which economic, social, and environmental factors come to the fore.

The final factor that potentially influences the project areas, besides the object and the context, is the process of urban regeneration itself. The structure of the government and decision/policy making was argued to be important in this process. In

Overall, this short study showed that the opportunities for urban regeneration in the three project areas along Istanbul’s Golden Horn are certainly present. By analysing the physical environment, the external influences, and the decision making process, different ways of looking at the same problem were provided. Examples of opportunities and limitations for urban regeneration were given for each viewpoint. Together, the different viewpoints provided a broad overview of the complex dynamics that play a role in urban regeneration.

Project Area 1:

Description of

5 Project Area One: Galata Tower

In this chapter, the first project area will be discussed: Galata Tower. The Galata Tower area centres around the Galata or Genoese Tower, built by Genoese in 1348. The Galata Tower area lies in the old part of Beyoğlu (see figure 1 on page 4 and figure 4 below). In the past, this part of Istanbul functioned as the international quarter called Pera. One can still notice the international past in the style of the buildings, and the presence of a church and an English hospital. Project area one lies completely within the former city walls, of which only a small part still remains.

Figure 2 The Galata Tower area on a satellite image. Source: Google Earth, 2006.

Function of the Area

Infrastructure and Traffic

The infrastructure in this part of the city is not developed enough to meet the modern-day standards. It is not easy to cross the area by car. The street surface is uneven and scattered with holes. Most of the streets are designated to facilitate two-way traffic. But, the narrow streets make it virtually impossible for cars to pass each other. It is unclear how the local people reach the small shops in the area. Buses and trams do not cross the area. This could have something to do with the small streets; there simply is no room for buses or trams. The easiest way to travel through the narrow streets is by foot. But this is only relatively easy, compared to travelling by car. The streets are very steep and it is hard to walk up the hill towards the Galata Tower. The earlier mentioned uneven street surface and holes make the walk even more difficult.

Heritage and Landmarks

The Galata Square is a meeting point for the local people. The benches provide a nice possibility for resting and waiting. Trees, an uncommon sight in this area, can provide the people with some shade. The trees and benches make the Galata Square a point of rest in the busy city life of Istanbul.

The Galata Tower (figure 5) is only one of the minor attractions in Istanbul, but one can find tourists climbing it the whole day. In the top of the tower is a restaurant and night club (figure 6). In this way the Galata Tower has found a new use and that guarantees a proper maintenance of the heritage. But the restaurant and night club were not packed with people during the hours that we visited them. The business on top of the tower seems not to be thriving during the day. At night, this is different.

Another piece of heritage that is present in project area one is the former city wall. The wall is in a deteriorated state and seems to play no significant role in the area. The fact that the wall plays no significant role can be explained by the size of the remnants of the wall and the visibility of it. Only one piece of the wall is still standing; it is now being used as a part of a building. This makes the wall not easy to notice, especially if you are not familiar with the area.

Open and Green Spaces

Project area one has little open or green space. There is one vacant lot (figure 7), which is quite large in comparison to the total size of the project area. Also, Galata Square (figure 8), discussed above as a landmark, can be classified as open space. The rest of the area is very densely built; this effect is strengthened by the narrow and steep streets (figure 9). This creates a dense atmosphere, where one can feel locked up. The narrow streets and the little amount of open space also cause disorientation. The Galata Tower is clearly visible from the Galata Bridge. But if one walks through the area towards the tower, one has no orientation, the tower out of sight. The tower only becomes visible when standing directly under it.

Figure 7 Vacant/underused lot Figure 8 The Galata Square

Environment

In case of a rain shower, the rain water flows over the streets. This water carries all kinds of rubbish through the streets. To improve the looks of the streets and prevent the dirt getting into the water system, a better sewage system should be constructed.

Parking

The parking facilities that are available in the area seem to be sufficient. They suit the needs of the shops that are present. Even a parking garage (figure 10) is available for visitors of the Galata Tower Region. A real problem is the delivery of supplies to the shops that only have a front entrance. Small cargo trucks are therefore blocking the narrow streets when they are making a delivery (figure 11). This cannot be seen as a parking problem as such, but it does cause congestion in the area.

Figure 10Parking Garage Figure 11 Obstruction by delivery of supplies

Walkability

Figure 52 Constrained walkability

Connectivity

Project area one is not well connected to its surrounding areas. To the North of the project area lies the new part of Beyoğlu which is internationally oriented. Commercial buildings and consulates are situated along a big shopping street, the Istiklal Caddesi (figure 13). A good connection between the old and the new part, between Galata Tower and the Istiklal Caddesi, is missing.

To the South of the area lies the Persembre Pasari (project area three) and the Galata Bridge. Tourists do not travel through project area one, because the roads cannot accommodate traffic through the area, and trams and buses cannot cross the area. As a result tourists take the underground train (the Tünel, figure 14) from Galata Bridge to Istiklal Caddesi and walk into this very busy shopping street, skipping the Galata Tower and its region.

Figure 13 Istiklal Caddesi Figure 14 The Tünel

Liveability

6 Project Area Three: Per

ş

embe Pazari

Project area three is called Perşembre Pasari, which means Thursday market. The area contains the small strip between around an arterial road, the Yüzbaşi Sabahattin Evren Caddesi, and the waterfront of the Golden Horn (see figure 1 on page 4 and figure 15 below) In the past, there stood a great wall that bordered the Golden Horn in this area, but from this wall there are no remnants.

Figure 15 The Perşembe Pazari area on a satellite image. Source: Google Earth, 2006.

Function of the Area

The Northern side of the Golden Horn is characterised by its clustered specialised shops. Here, one can find paint shops, hardware stores and fishing industry-related functions. The eye catcher of this area is the fishing market, on the shores of the Golden Horn (figure 16).

The area has a recreational function as well. Small private boats and green and open spaces occupy the shoreline. These boats and spaces stimulate the recreational fishing in the area.

Figure 16 Fishing market on the shores of the Golden Horn

Infrastructure and Traffic

The area is enclosed by an arterial road to the North, and the Atatürk and Galata Bridge on both sides. The area is easy accessible from Galata Bridge, but the other infrastructure forms a barrier for pedestrians. It is not easy to cross the streets because of the amount of traffic and the lack of pedestrian crossings (figure 17). Therefore, it is difficult for pedestrians to go through this area to a destination in another area.

Heritage and Landmarks

Only a small amount of heritage is present in project area three. The only building that could be regarded as heritage is the Azap Kapi Mosque, a building that was rescued from ruin when the Atatürk Bridge was built in 1942. The mosque is somewhat overshadowed by the amount of noise caused by the traffic that crosses the bridge.

The rest of the buildings in project area three cannot be regarded as heritage; most of them are derelict, underused buildings. The collapsed buildings give the area a negative image. The sites of the collapsed buildings look very disorderly with all the rubble and rubbish.

Open and Green Spaces

There is a lot of green and open space in project area three, but most of the space is deprived (figure 18). The buildings in the first line (seen from the water) are deteriorated or collapsed, creating open spaces. This makes the area seemingly less busy, and the sunlight can create an open atmosphere. The collapsed buildings provide the city planners and architects with opportunities. Housing prices are probably low in this area, so regeneration or renewal can easily be afforded.

Figure 18 Garbage on vacant lot near waterfront Figure 19 Small fishing boats at the waterfront

Use of Waterfront

Environment

The derelict buildings provide opportunities to dump garbage illegally. The same accounts for the neglected parks, where a lot of rubbish can be found in the grass (figure 20). Of course, this is an environmental problem, which should be dealt with appropriately. A solution could be to place garbage cans. These garbage cans are totally absent in the area.

Figure 20 Deteriorated green space at the waterfront

Parking

The opportunities to park differ in the area. Along the Yüzbaşi Sabahattin Evren Caddesi it is virtually impossible to find an open spot to park your car. On top of that, the road is meant for through traffic which makes it hard to exit the road. So the visitors of the shops and the commercial buildings this road can have problems finding a place to park their cars.

It could prove to be easier to park your car in the area between the waterfront and the Yüzbaşi Sabahattin Evren Caddesi. This area contains a lot of open space which could be used for parking purposes.

Walkability

Connectivity

The arterial road in the North of project area three forms a barrier to the Galata Tower Region, project area one. The connection between the Galata Bridge and project area three is good; the area is easy to reach by foot. At the other side of the area, it is hard to reach the area from Atatürk Bridge by foot. By car, the area is also hard to reach. The roads that surround the area mainly serve ongoing traffic. Overall, the poor connectivity makes the area a bit isolated. This isolation causes the area to remain quiet and peaceful, in contrast to project area four.

Liveability

7 Project Area Four: Eminönü

Eminönü is the third area researched in this study and is situated south of the Golden Horn (see figure 1 on page 4 and figure 21 below). The most noticeable aspect of the area is its busy traffic, but of course there is more than just that. In the following the area is discussed according to the elements outlined in the introduction.

Figure 21 The Eminönü area on a satellite image. Source: Google Earth, 2006.

Function of the Area

Figure 22 The Spice Bazaar in Eminönü Figure 23 Shopping street in Eminönü

Infrastructure and Traffic

Main transportation routes from both east and west are meeting in the middle of the Eminönü area. They connect to the Galata Bridge. These roads are rather large and form a large contrast with the small, alley-like roads further from the coast line, down south. The whole area is crowded with traffic. Congestion is very common. The small roads are blocked once a car is driving thru, which happens all day long. The main roads suffer from the same problem; not due to their size, but due to the enormous amount of traffic, especially during peak hours (figure 24).

Besides cars, there are many other forms of transportation being used in this area. First of all, there are many pedestrians, coming from all directions, but mainly north-south and vice versa. The main reasons for this are the public transportation facilities along the south shore of the Golden Horn. There is the light rail that crosses the Galata Bridge and, not to forget, many taxis. There also is a bus station just west of the bridge, which is crowded with both passengers and buses. It has a chaotic appearance, because buses and pedestrians cross each other unregulated and there are no special bus platforms, merely a large asphalt area (figure 25). Finally, there are many passenger boats, bringing their passengers in virtually every direction. They are all anchored along the shore, without the use of piers.

Heritage and Landmarks

The area is rich in religious and cultural heritage. The Yeni Camii (New Mosque) is the most recognisable (figure 26). This mosque is still being used by lots of people. It also functions as a clear landmark, being a large building and at the foot of the Galata Bridge, which makes it perfectly visible from the opposite side of the Golden Horn. Directly next to the New Mosque, there is another large building, the Spice Bazaar. The market stands in- and outside the building are very busy during opening hours. Besides these two large buildings, there are two other mosques in the west part of the area, located at the opposite side of the plaza. These are the Ahmet Paşa Camii and the Rüstem Paşa Camii. Other heritage is some small city-wall remaining and the structure of small, narrow streets with many shops.

Open and Green Spaces

Green space is not present in the project area. There are some trees, but only a few. Open space is present in the form of a large plaza in between the shore, New Mosque and the shopping area (figure 27 and 28). This contrasts with the narrow shopping streets, where underused and vacant lots are the only form of open space, which is not a lot.

Figure 27 The plaza seen from the New Mosque Figure 28 The plaza and the Rüstem Paşa Camii

Use of the Waterfront

The waterfront is merely used for the anchoring of passenger boats (figure 29 and 30). This makes the waterfront a crowded place, but the people are only transferring here and thus passing by. There is no place where the waterfront is used for some kind of leisure activity, like people sitting on benches along the shore. However, it is understandable that leisure does not take place in such crowded transport areas as this part of Eminönü. The only exception to this are some fishermen who do not seem to mind the traffic and noise.

Environment

The area has a decent and clean appearance. There is not much garbage on the streets, except for some places in the narrow shopping streets. Although the visual appearance might be alright, the air for example cannot be very clean. The exhaust of many cars, old buses and old boats causes this. However, this cannot be proved in this research and environmental research will be needed here. The final aspect that is remarkable is the near-flooding of the open spaces when rain is falling, because there is little drainage and virtually no permeable surface.

Parking

Except for a few parking spaces at the side of the plaza there is almost no parking space available in the area. Logically, the pressure on those parking spaces is high and parking is a real problem in the area.

Walkability

Overall, it is fairly easy to get around the area by foot, especially when the transportion function of the area is taken into account. Coming form the Galata Bridge, there is an underground passage of the main road, leading pedestrians to the plaza (figure 31 and 32). Although a lot of stairs have to be taken, which is undoable for disabled persons, the majority of the people can easily use these passages. The passages are also used for shops that are located under the road. Because of this the passages have a public and lively character.

The disadvantages for the remaining of the area consist of three main points. First of all, there is the problem of the cars going through the crowded and narrow streets, making the pedestrians wait against the shop windows. Secondly, the lack of drainage makes the uncovered areas not easily accessible. The consequence of that is less pedestrian activity during rainy periods. The final point of concern is the lack of signage. An example of this is the underground passage of the main road. A first-time visitor will not have the slightest idea where that passage leads to and will probably decide to cross the road on ground level. Signage might solve this.

Connectivity

In terms of function the area fits into its surroundings. Therefore, in general, the area is well connected to its surroundings, being a major transportation hub. The only setback at this point might be the traffic congestion, which makes it more difficult to cross the area, mainly by car. The connection to the waterfront, however, is almost not present. It is only a connection in terms of transportation (the ferry boats).

Liveability

References

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (2006), Context, fourth edition, http://www.answers.com/context&r=67. Accessed November 14, 2006

Bertolini, L. and T. Spit (1998), “Railway Station Area Redevelopment in the Spotlight”. In: L. Bertolini and T. Spit,

Cities on Rails: The Redevelopment of Railway Station Areas. London: Routledge.

Couch, C. et al. (Eds.), (2003), Urban Regeneration in Europe, Blackwell Science Ltd, Oxford.

De Roo, G. (2001), Planning Per Se, Planning Per Saldo, third edition, Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag.

Dura Vermeer (2006), Amphibious Houses at Maasbommel, The Netherlands,

http://www.drijvendestad.nl/sites/drijvendestad/tekst_ddwoning_uk.html. Accessed November 15, 2006.

Geddes, P. (1915), Cities in Evolution, Williams & Norgate, London.

Grava, S. et al. (2002), Disaster Resistant Istanbul: Urban Planning Studio Spring 2002. Columbia University, New York (unpublished).

Hague, C. (2005), “Planning and Place Identity”. In: Place Identity, Participation and Planning, Hague, C. and P. Jenkins (eds.) Routledge, Oxfordshire.

Home, R.K. (1982), Inner City Regeneration, E. & F.N. Spon Ltd., London.

Jenkins, P. (2005), “Space, Place and Territory: an Analytical Framework”. In: Place Identity, Participation and Planning, Hague, C. and P. Jenkins (Eds.) Routledge, Oxfordshire.

Knox, P.L. and S.A. Marston (2003), Places and Regions in Global Context: Human Geography, updated second edition, Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

LeGates, R.T. and F. Stout (Eds.) (2000), The City Reader, third edition, Taylor & Francis, London.

Nicholls, R.J. (1995), “Coastal Megacities and Climate Change”. In: GeoJournal, vol.37, no.3, pp.369-79, Kluwer Academic Publishers

OECD Statistics (2006), Turkey OECD.Stat data,

http://stats.oecd.org/WBOS/ViewHTML.aspx?QueryName=201&QueryType=View&Lang=en. Accessed November 14, 2006.

Proshansky, H.M. et al. (2000), In: Creating a Sense of Place: the Vietnamese-Americans and Little Saigon, Mazumdar, S. et al., Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 319-33.

Roberts, P. and H. Sykes (Eds.) (2000), Urban Regeneration: A Handbook, Sage Publications Ltd., London.

Rose, G. (1995), “Place and Identity: a Sense of Place”. In: A Place in the World?, Massey, D. and P. Jess (Eds.), Oxford University Press, New York.

Rosen, M.A. & I. Dincer (2001), Exergy as the Confluence of Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development,

Exergy International Journal, 1(1), 3-13.

Rutherford, J. (1990), “A Place Called Home: Identity and the Cultural Politics of Difference”. In: Place and Identity: a Sense of Place, Rose, G., Oxford University Press, New York.

Steuteville, R. and P. Langdon (Eds.) (2003), New Urbanism: Comprehensive Report & Best Practices Guide, third edition, New Urban Publications Inc, Ithaca, New York.

The New York Times (2005), A City of Many Pasts Embraces the Future, R. Lyman, September 25, 2005 http://www.nytimes.com. Accessed November 14, 2006

Tuan, Y.F. (1977), Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, Edward Arnold, London.

Twigger-Ross, C. L. and D.L. Uzzell (2000), In: Creating a Sense of Place: the Vietnamese-Americans and Little Saigon, Mazumdar, S. et al., Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 319-33.