William Blake and

the Body

William Blake and

the Body

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission.

No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP.

Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published 2002 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010

Companies and representatives throughout the world

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries.

ISBN 0–333–96848–4

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Connolly, Tristanne, J., 1970–

William Blake and the body / Tristanne J. Connolly. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-333-96848-4

1. Blake, William, 1757–1827 – Criticism and interpretation.

2. Blake, William, 1757–1827 – Knowledge – Anatomy. 3. Body, Human, in literature. 4. Body, Human, in art. I. Title.

PR4148.B57 .C66 2002

821¢.7 – dc21 2002025210 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

List of Illustrations vi

Preface vii

List of Abbreviations xvii

1 Textual Bodies 1

2 Graphic Bodies 25

3 Embodiment: Urizen 73

4 Embodiment: Reuben 95

5 Divisions and Comminglings: Sons and Daughters 125

6 Divisions and Comminglings: Emanations and Spectres 155

7 The Eternal Body 192

Notes 222

Bibliography 232

Index 241

List of Illustrations

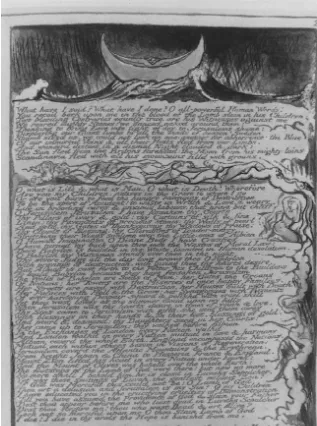

Frontispiece William Blake. Visions of the Daughters of Albion. Plate 2(1). Reproduced with permission from the William Blake Trust’s

edition of Blake’s Illuminated Books. ii

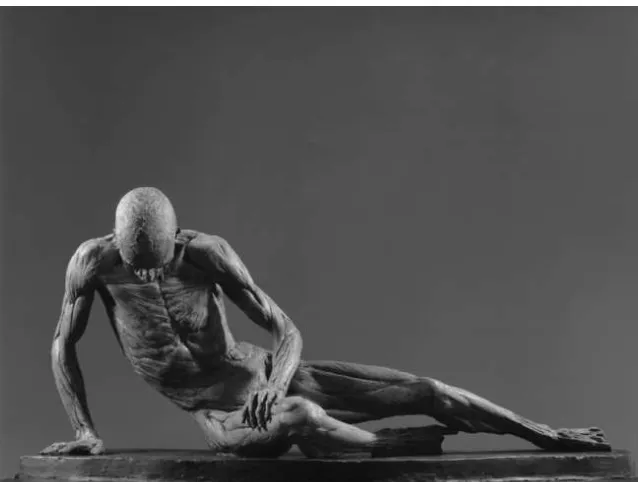

2.1 William Blake. Elohim Creating Adam. © Tate, London 2001. 26 2.2 W. Pink after Agostino Carlini. Smugglerius. Royal Academy

of Arts, London. 36

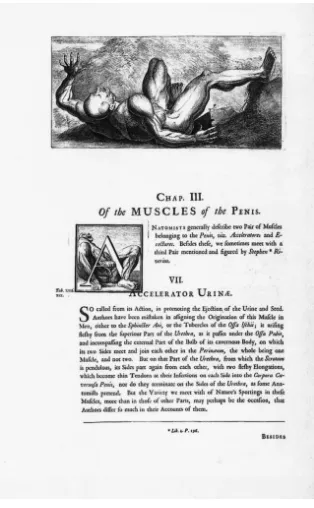

2.3 William Cowper. Myotomia Reformata. Page 8. The

Wellcome Library, London. 49

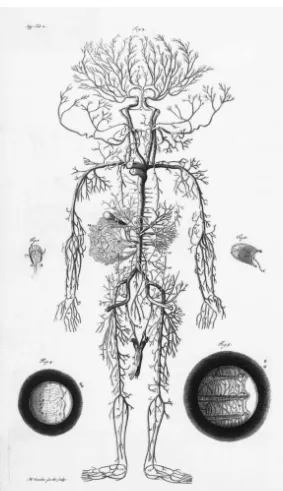

2.4 William Cowper. Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Table 45. The

Wellcome Library, London. 50

2.5 William Cowper. Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Appendix 3.

The Wellcome Library, London. 51

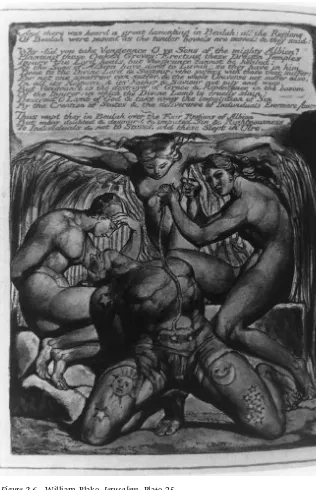

2.6 William Blake. Jerusalem.Plate 25. Reproduced with permission from the William Blake Trust’s edition of

Blake’s Illuminated Books. 52

2.7 William Blake. Jerusalem.Plate 24. Reproduced with permission from the William Blake Trust’s edition

of Blake’s Illuminated Books. 54

2.8 William Blake. Visions of the Daughters of Albion. Plate 6. Reproduced with permission from the William Blake

Trust’s edition of Blake’s Illuminated Books. 55

2.9 William Cowper. Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Table 60.

The Wellcome Library, London. 56

2.10 William Cowper. Anatomy of Humane Bodies. Table 62.

The Wellcome Library, London. 57

5.1 William Blake. Jerusalem.Plate 69. Reproduced with permission from the William Blake Trust’s edition of

Blake’s Illuminated Books. 150

5.2 Francesco Saverio Clavigero. A History of Mexico. 1787. Plate viii, page 279. Benson Latin American Collection.

University of Texas at Austin. 151

6.1 William Blake. Jerusalem.Plate 35 [31]. Reproduced with permission from the William Blake Trust’s edition of

Blake’s Illuminated Books. 161

7.1 William Blake. Jerusalem. Plate 95. Reproduced with permission from the William Blake Trust’s edition of

Blake’s Illuminated Books. 200

Preface

One would think there would be nothing more to say about the body in general, or the body in Blake. ‘The Human Form Divine’ is Blake’s self-proclaimed central image and ultimate reality; the human body is what we live in every day, what we are, what is most familiar to us. Yet, the body is as alien as it is commonplace, as unfathomable as it is known: think of how many involuntary movements, such as heartbeat, are essential to its regular functioning, and how unexpectedly and inexorably disease and death can overtake the body. Blake’s depiction of the body communicates this: the body both provides and threatens identity. The simple question, ‘What does Blake think of the body?’, is difficult to answer, even though understanding the significance of his main preoccupation would be essential to understanding his work. The body is Blake’s preoccupation not because of a confident admi-ration of it, but rather a troubled obsession. He has a love/hate relationship with his favourite image; he at once reviles and glorifies the human body. This paradox could be swiftly resolved by claiming that, in fact, there are not really any bodies in Blake at all. The things that happen to Blake’s charac-ters could not happen to real bodies: wives do not burst from their husbands’ chests in globes of blood; poets do not possess other poets by entering their left feet in the form of falling stars; and the city of London is not normally accessed by entering anyone’s bosom. These are symbolic characters, it could be argued: allegories whose bodies are mere vehicles for meaning. If Blake’s were a simple dualism, then not only his characters’ bodies, but also the real human body, would be only vehicles which could be discarded for the sake of their more valuable contents. However, not even the most stilted allegory can completely transcend the symbols which embody its meaning, and Blake’s allegory is much more a tangled web than a nut in a shell. He takes his symbols very seriously. Coleridge saw in Blake a ‘despotism of symbols’, and Yeats christened Blake with the title, ‘literal realist of the imagination’ (Coleridge, in Bentley, Critical Heritage55; Yeats 119). Blake’s allegorical char-acters are endowed in both design and verse with bones and blood, fibres and flesh; indeed, they are depicted in all gory detail. Because of this, I take them as bodies; because Blake presents them as bodies, he must be making statements on the body through his choice of images. The statements he makes do not boil down to another possible simple answer, that the physi-cal body is bad and the spiritual body good and both ultimately separate from each other. Blake often caricatures the mortal body as pathetic, restric-tive and painful, and there is truth in his exaggeration: again, think of all that cannot be controlled and all that must be suffered in mortal human form. Yet, his adulation is not saved exclusively for incorporeal spiritual

forms. He often celebrates sexuality, and even admires nerves and organs. In the end, those nerves and organs are immortalized, making Blake’s eternal body most definitely a body.

Because the body is basic to human experience and fundamental to Blake’s art and verse, it is an inexhaustible topic. Anthropologist Mary Douglas argues that ‘the body is a model which can stand for any bounded system’ (115). Because the range of the body’s symbolism is so broad, thinking about the body involves thinking about other things. The result is that, though there has been recently a tangible wave of interest in writing about the body, the works which represent it do not necessarily cohere into a body of work on one subject. Of course they do not all see the body as having the same significance, because they study the body through various disciplines, and in various cultures of various eras. But even beyond this variation, different works on the body attach themselves to vastly different issues. There are economic bodies, political bodies, medical bodies, sexual bodies, and more, each with numerous subdivisions and interrelations. A book on Blake and the body could be about many things; too many things. The way I ap-proached the topic was to read Blake’s works and categorize the different kinds of bodies I perceived there; having categorized them, I would try to determine the characteristics of each category, and explore the significance of those characteristics through whichever historical, cultural and literary contexts they suggested. The general categories I deduced were: texts as bodies; bodies in Blake’s designs; bodies coming into existence, or being shaped; bodies which split off from or fuse with other bodies; the ideal, eternal body; bodies which dissolve into landscapes; bodies which are also places, such as cities or countries. To focus the project, I decided that its border would be the border between the body and the world. Considering Blake’s bodies in relationship to their environment, and as symbols of nations or political systems, would be a fruitful topic for a separate study; there is a wealth of material, some of it already approached from a differ-ent direction in Jason Whittaker’s William Blake and the Myths of Britain. That the remaining categories continued to shape my work will be seen from a glance at the Contents list, and the chapter outline provided at the end of this preface. Concentrating on how bodies are formed and connect with each other lent itself to a number of contexts, one of the most central being gender.

distinction in Blake can be a convenient trapdoor to save him from many sins: anything unpalatable can be explained away as fallen. Because one might hope to find Blake’s ideals, unfiltered through any point of view, in the eternal realm, the question of Blake’s feminism or lack of it devolves to a great extent on the place of the female in eternity.

Though Blake creates a seemingly equal unification of male and female in eternity, that ‘human’ is overridingly male. Jean Hagstrum, in The Romantic Body, contends that ‘Blake did break away from the prison of his own sex long enough to define and envision an intersexual world of intense mutuality and equality’ (140), but his arguments are undermined by embarrassed explanations of exceptions. A good example of the difficulties Hagstrum runs into is found in his response to the most problematic passage for defenders of a non-misogynist Blake:

It is true that Blake says that in Eternity woman ‘has no Will of her own’ (Last Judgment, E., 562). But if woman is denied will in Eternity, we should remember that under the Covenant of Forgiveness the new and gentle Jehovah also lacks will. . . . Will tends to be absent from the state of highest fulfillment: other qualities and other quests and a different orientation toward the self make it irrelevant or obtrusive. So it is no loss that Jerusalem in particular and idealized women in general lack it.

(138)

Hagstrum must fudge definitions to hold his point; and he does not take on Blake’s preceding words which indicate that the absence of will is due to ‘Woman’ being ‘the Emanation of Man’. Brenda Webster finds, ‘although Blake announces the end of sexual organization, male sexuality continues to stand as a model for the human, while the female is either incorporated or isolated restrictively in Beulah’. She holds that ‘in his late Christian prophecies, Milton and Jerusalem, [Blake] suggests that the female should cease even to exist independently and become reabsorbed into the body of man where she belongs’ (‘Sexuality’ 203, 194). Alicia Ostriker agrees: ‘at its most extreme, Blake’s vision goes beyond proposing an ideal of dominance-submission or priority-inferiority between the genders’ (which is bad enough). ‘Blake wishfully imagines that the female can be re-absorbed by the male, be contained within him, and exist Edenically not as a substan-tial being but as an attribute . . . the ideal female functions as a medium of interchange among real, that is to say male, beings’ (163). Essick, in his article, ‘William Blake’s “Female Will” and its Biographical Context’, con-siders the argument that

divi-sion to figure forth more fundamental psychological and metaphysical problems.

(616)

One might ask, what is a more fundamental problem than sexual division? One might also ask, if ‘they’ figure forth otherness in the ‘human’ psyche, does that not exclude ‘females’ from the category of the ‘human’? From a female point of view, the female is not other. Essick finds ‘forceful rebuttals’ offered by ‘feminist critics’, including this: ‘the argument that females are the metaphoric vehicles for genderless meanings is blind to how tropes, and a poet’s choice of the lingual signs he manipulates into tropes, carry unavoidable ideological orientations, in part through their non-metaphoric references’ (Essick, ‘Female Will’ 617). Especially since Blake’s personifica-tions are so fleshy, it is difficult to consider his use of gender as mere metaphor. There is nothing ‘mere’ about metaphors, which can turn the supposedly genderless Christian God into a father and an old man. The critics Essick refers to are David Aers, Diana Hume George and Susan Fox. Aers finds that Blake’s use of ‘dominant male ideology . . . inevitably feeds back into the realm of human interrelations from which it has been derived’ (37). For George, ‘Blake’s portrayals of sexuality and of women . . . are prob-lems of symbol formation that express themselves in the limitations of language’ (199). Fox will not discount either of two ‘conflicting attitudes’: metaphor cannot ‘apologize away Blake’s occasional shrillness towards women’, yet ‘one cannot ignore the abstract quality of his sexual divisions, because to do so is to miss the vastest implications of his observations and to make those observations much more strident and condemnatory than we have evidence they were meant to be’ (509). Such equivocation weakens her position, falling into apology. Shrillness may be part of Blake’s ‘vastest implications’.

reconciliation of contraries so that one of them disappears; rather, it is an attempt to answer a rather Lockean personal identity question posed by David Punter, which for me sums up the Blake gender debate: ‘We are forced to ask how it can be that the same writer who sees so acutely into the pressures on individuals caused by ethical rigidity and repression seems at the same time to construct such an apparently male supremacist space’ (‘Trauma’ 481). Like Punter, I feel disappointed in Blake, because he makes a conscientious effort toward gender inclusiveness, and to a certain extent succeeds, but not completely. He does not go far enough. What blocks him? A dark epiphany, placed at a certain historical moment, is not a fully ade-quate answer. His later works are not devoid of fervour for sexual and politi-cal liberty combined: there is the response to trials of homosexuals in Milton found by Christopher Hobson; there are the eloquent pleas of Jerusalem and Mary for forgiveness of sexual sin and against warlike sacrificial violence (Hobson, 113–43; J 20–2, 61). Likewise, his earlier works are not devoid of misogynist hints, or at least bugs in any system of Blakean feminism. There is in Visions of the Daughters of Albionthe ‘harem fantasy’ which, for Helen Bruder, ‘marks the moment of Oothoon’s most acute apostasy, as she offers to become an energetically ensnaring procuress’ (82) as an early indication that if Blake’s women are liberated, they are liberated to give sexual plea-sure to men. There is in The First Book of Urizen Enitharmon as ‘the first female now separate’ (16:10) as a foreshadowing echo of that embarrassing later statement that in Eternity the female has no will of her own. More arguably, there is the failure of both Thel and Oothoon to get what they want – perhaps a compassionate presentation of women’s frustration, perhaps even an endorsement of female community among the daughters of Albion and in the vales of Har – but why not an imagining of female freedom? Why only sympathy for women in a female sphere, and women who fail? If Blake does not envision a full equality between genders and lib-eration for both, it is not because he could not, but because he would not. As Punter suggests, Blake was able to see through many values which were imposed as unquestionable by his society. Other concerns more important to him clashed with the project of imagining female equality and liberty, and delineating these concerns will be a task of the following chapters.

Bruder’s book is a masterwork of new historicist criticism. She takes by the scruff of its neck the rather flabby argument that apologizes for Blake’s views of women by appealing to the limitations of his historical context, and tests it mercilessly, with positive and fascinating results. She pursues in detail the question of what feminism was in the 1790s, and places Blake in it as a rather forward-looking figure. However, she still finds flaws in Blake’s femi-nism, such as that action of Oothoon’s; she ascribes Oothoon’s failure to ‘historical considerations’ which forbid the conception of a solution (88). Other scholars notable for historicizing Blake are Jon Mee and David Worrall. In order to give precision to their researches, it was wise for them to concentrate on Blake’s earlier works. Their practice of contextualizing Blake in the high and low culture of Britain of his time is illuminating, though, not just to works produced in the 1790s; my study, taking in Blake’s whole oeuvre, carries this approach through his later prophecies (counter-ing their reputation as otherworldly). Hobson and I both take advantage of the best of both worlds, combining gender criticism with historicism. Hobson takes a queer theory perspective on Blake, while mine is a wider gender studies one; Hobson considers Blake to succeed in endorsing and empowering liberty for male and female, heterosexual and homosexual, while I examine the shortcomings of his ideals, and the motivations which contribute to them. Though it was back in 1982 that W.J.T. Mitchell pre-dicted critics would ‘rediscover the dangerous Blake’ since he was ‘now safely canonized’ and ‘ready to take a little abuse’, the need and profit of such an approach continues (Mitchell 410 –11). Hobson, who notes that critics in the 1980s and 1990s largely ignored Mitchell’s exhortations, explicitly responds to the questions Mitchell asks about Blake’s obscenity (Hobson xii). My impulse to confront the dangerous Blake comes from a deep conviction of the strangeness of his work, that to normalize him is to lose something valuable, even at the price of finding something undesirable. Blake is scary; a good part of the power of his work derives from its bizarreness, a good part of which in turn derives from his simultaneous adoration and abomi-nation of the human body.

imi-tations or parodies, is that of the ideal, eternal body, which occupies the study’s final chapter.

The questions of whether identity is defined or protean, how identity is affected by birth, and how language and literature are affected by these con-cerns, beg for comparison with Julia Kristeva’s theories of the semiotic, the symbolic, and the abject. Despite their similar concerns, Kristeva is rarely considered in relation to Blake. They both struggle with the advantages of having a flexible identity, and the dangers of being scattered and undefined. Digging back into the origins of Kristeva’s thought, I find that Mary Douglas’ theories in Purity and Danger(which Kristeva makes use of in Powers of Horror) are also a valuable way to explain the dynamic of the relationship Blake envisions between his bodily text and its reader. Blake makes use of what Douglas would call the sacredness of bodily borders to gain a certain degree of control over who his audience is and how they read his works. Blake creates different kinds of entry points, or orifices, in his works: while they allow readers access to the body that is the text, the transgression they require of readers ensures that the squeamish are repulsed, while the brave are challenged.

and the possibilities of malformation and miscarriage. Blake’s metamorphic foetal imagery takes off from Ovid’s process-fascinated descriptions of change to suggest that the new, strange form is our familiar human body. It also reflects the protean nature of Blake’s creative works; the meaning of Blake’s birth imagery applies equally to humans and artworks. The terrify-ing aspect of uncanny growth and change culminates in miscarriage imagery through which Blake depicts the failure of creation, both human and artis-tic. I offer some evidence for a biographical basis for Blake’s treatment of miscarriage in his poetry (Catherine Blake possibly suffering one or more failed pregnancies), but I concentrate on explicating Blake’s poetic imagery. From it I conclude that Blake ‘perversely’ values nonreproductive sexuality. He expands the possibilities of what sexual activity can produce, such as personified emotions and artworks.

From the bizarre birth of Urizen and the failed birth of Reuben, I move on to examine one of the few Blake characters born normally, from a woman’s womb: Orc. Through studying the Oedipal suggestions of his nativ-ity, alongside its origins in Satan’s family romance with Sin and Death in Paradise Lost, I demonstrate that in Blake, children (and mothers) can be seen as facets of the father’s personality: each human is a family. At times proliferating, and at times reuniting in monstrous conglomerated forms, the children of Albion enable Blake to present a vast confusion of diver-sification and unification. I argue that sons and daughters (along with emanations and spectres, the subject of the next chapter) dramatize the multiplicity inherent in the Blakean human. The work of RenJ Girard allows me to connect the identity-blurring involved in Oedipal relationships to the acts of human sacrifice perpetrated by the Sons and Daughters of Albion in Blake’s Jerusalem. They are flesh-bound attempts to establish individual iden-tity and cross bodily borders.

That Blake’s human is manifold in itself, not just in its offspring or its fallen manifestations, is revealed by his depiction of emanations and spec-tres. Emanations and spectres split, painfully and gorily, from the human of whom they are constituent parts: psychic components separate and become independent personifications. This divisibility of both flesh and spirit I show to be an exaggerated outgrowth of Locke’s and Hume’s questioning of per-sonal identity. Unlike the emanations of another manifold being – Wisdom and the Devil, and the Son and the Spirit as personified aspects of God – the intellectual births from Blake’s ‘Human Form Divine’ are depicted viscerally. Their separations are fantasies of male mothering which reflect on other creative processes, especially that of Blake’s illuminated books in which they are described and pictured. Emanations and spectres, like God’s hypostases, can help, hinder, and even become, creative productions.

con-centrates on Blake’s few tantalizing suggestions of what life in eternity is like. From these I attempt to describe the appearance and function of the resurrected body. The presence of organs of sense indicates that for Blake the ideal human form is not a disembodied spirit. The imaginings of Locke, Berkeley, Swedenborg, St Teresa and St Paul on eternal bodies inspire an orig-inal ideal in which transparency and interpenetrability are valued as highly as individual identity. The conversational and sexual ‘intercourse’ through which ideas are embodied in eternity is an apotheosis of male homosexual relations which harnesses the power of female sexuality. This leads me to confront the question of why androgyny often veils a male form which incorporates the female, rather than a genderless, or equally male and female, ideal. I suggest that Blake’s final triumph over dualism is made pos-sible, yet made incomplete, by subordination.

have continued to aid and advise me, especially Alvin Lee and David Clark; and, at Auburn, Paula Backscheider for her unbeatable mentoring. Thanks to Patricia Simmons for, in so many ways through good and ill, being my fellow Daughter of the Empire. To those who often provided practical help as well as warm friendship – Leo Sharpston and (in honoured memory) David Lyon, George and Hilary Pattison, Margaret Watson (as well as Linda, Josie and Marleen) – thanks. To Krista Johansen, for friendship: swylc sceolde secg wesan, þegn æt Qearfe! Heartfelt thanks to my family: all the Noreyko

List of Abbreviations

Unless otherwise indicated, all references to Blake’s unengraved writings are taken from Erdman’s edition and cited by page number (except for The Four Zoasfor which Night and line numbers are also provided), and all references to Blake’s illuminated books are taken from the Blake Trust series and cited by plate and line number. References to the notes from the Blake Trust edition will be introduced as such, and cited by page number.

E Erdman, Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake.

In Erdman:

FZ The Four Zoas

AR Annotations to Reynolds

DC A Descriptive Catalogue VLJ A Vision of the Last Judgment PA Public Address

In the Blake Trust editions:

SIE Songs of Innocence and of Experience BT The Book of Thel

MHH The Marriage of Heaven and Hell VDA Visions of the Daughters of Albion E Europe: a Prophecy

A America: a Prophecy BU The First Book of Urizen BL The Book of Los BA The Book of Ahania M Milton: a Poem

L Laocöon

J Jerusalem

Unless otherwise indicated, definitions and biblical quotations are taken from the following, which, when mentioned, are named by these abbreviations:

OED Oxford English Dictionary KJV The Bible, King James Version

ag

1

Textual Bodies

When Ezekiel is called to be a prophet, to speak to the hard-hearted chil-dren of Israel, the voice that speaks to him from his vision makes a remark-able request:

But thou, son of man, hear what I say unto thee; Be not thou rebellious like that rebellious house: open thy mouth, and eat that I give thee. And when I looked, behold, an hand was sent unto me; and lo, a roll of a book was therein; And he spread it before me; and it was written within and without: and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe. Moreover he said unto me, Son of man, eat that thou findest; eat this roll, and go speak unto the house of Israel. So I opened my mouth, and he caused me to eat that roll. And he said unto me, Son of man, cause thy belly to eat, and fill thy bowels with this roll that I give thee. Then did I eat it; and it was in my mouth as honey for sweetness.

(Ezek. 2:8–3:3)

In Ezekiel’s introduction to his mission, there is an emphasis on rebellion versus obedience, and the unlikelihood that his audience will listen to him. Eating the scroll goes against the usual rules; something is ingested which normally remains outside the body. However, reading is an ingestion, if not usually such a complete one: a reader eats up written words with his or her eyes. This episode suggests becoming one with the text, making it com-pletely part of oneself in order to deliver its message loyally and powerfully under circumstances adverse to communication. It also suggests that going against the common conventions of what remains inside and what outside the body is part of prophecy. The voice also assures Ezekiel, ‘And they, whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear, (for they are a rebel-lious house,) yet shall know that there hath been a prophet among them’ (Ezek. 2:5). Ezekiel will affect his audience – make them react, leave an impression on them – even if they do not wish to listen. According to the voice, someone who is not rebellious eats what is given, receives completely

without questioning or being picky. This is what the prophet should do, but this is not what his audience will do. The strange crossing of bodily borders, in eating the scroll, has something to do with getting through to an unre-ceptive audience.

The unreceptive audience is a dilemma of prophecy: why would redemp-tive words be needed if all were already open to divine truth? William Blake’s illuminated books are also prophecies which try to work a redemptive purpose, and recognize that they are not preaching to the converted. However, Blake’s books are the opposite of Ezekiel’s scroll: they are more likely to swallow up their readers. Blake sees his illuminated books as human forms. When, at the beginning of his final prophecy Jerusalem, he announces, ‘I again display my Giant Forms to the Public’, he refers at once to his illuminated books, and the titanic characters they contain. Reading the weighty Jerusalem, then, is like being swallowed up by a Giant Form, entering its body. Blake continues, ‘My former Giants & Fairies having reciev’d the highest reward possible’, connecting the personification of his books to their appreciation by his audience. He strongly asserts the salvific potential of his writing: he claims to hear God speak, and proclaims, ‘There-fore I print; nor vain my types shall be: / Heaven, Earth & Hell, henceforth shall live in harmony’ (J 3). By using vocabulary specific to his medium, ‘print’ and ‘types’, Blake links the supposed power of his work to its form. However, this sanguine attitude is marred by the gouging out of words from the engraving plate. For example, one line with deletions reads, ‘Therefore Reader, what you do not approve, & me for this energetic exertion of my talent’ (3). Friendliness toward the reader is struck out, as is confidence in the reader’s reaction.

The fact that Blake created his own books, designing, writing, engra-ving, printing, finishing and binding them, at once enables him to claim an intimate relationship with, and strong influence over, his reader, and to illustrate dramatically the failure of that claim on plate 3 of Jerusalem. The unique form of Blake’s illuminated books makes them at first glance a dif-ferent kind of text, a corpus embodied in a difdif-ferent way. They require aware-ness of the textual body. Unlike poetry embodied in words only, Blake’s illuminated works cannot be fully reincarnated in any typeface; their body and soul are integrated. Handmade, they include hints of the process of their making. Existing between print and manuscript, they emphasize transgres-sion of categories. Depicting characters who enter each other and are part of each other, they dramatize the instability of bodily borders. From these characteristics Blake draws prophetic powers for his illuminated books, to achieve a transformative purpose, and to gain some control over his audi-ence: what kind of readers he will have, and how they will be affected.

on that subject: Mary Douglas and Julia Kristeva. Douglas, writing from an anthropological point of view and thus focusing on the social meaning of the body, seeks in her study Purity and Danger to unravel the relation-ship between the unclean and the sacred. She looks at the abominations of Leviticus, among other purity laws, to discover what characteristics cause the unclean to be considered unclean. She comes to the conclusion that ‘holiness is exemplified by completeness. Holiness requires that individuals shall conform to the class to which they belong. And holiness requires that different classes of things shall not be confused’ (53). Conversely, anything that crosses categories or borders is an abomination. Douglas pays particu-lar attention to defilement that relates to the body. When writing about ‘the symbolism worked upon the human body’ in ritual, she argues:

the body is a model which can stand for any bounded system. Its bound-aries can represent any boundbound-aries which are threatened or precarious. The body is a complex structure. The functions of its different parts and their relation afford a source of symbols for other complex structures. We cannot possibly interpret rituals concerning excreta, breast milk, saliva and the rest unless we are prepared to see in the body a symbol of society, and to see the powers and dangers credited to social structure reproduced in small on the human body.

(115)

As an anthropologist, she concentrates on society as the system symbolized by the body, but indicates that the body can stand for any system: for instance, a system of language or of thought. By saying ‘powers and dangers’ are ‘credited to social structure’, she implies that these are not absolute, but rather invented to support the system. Perhaps, then, this can be applied to other systems: the borders of language, mental operations, and the body itself can be seen as arbitrary, kept in place through the threat of danger. It is possible to distort these boundaries since they are not absolute. Douglas writes:

all margins are dangerous. If they are pulled this way or that the shape of fundamental experience is altered. Any structure of ideas is vulnerable at its margins. We should expect the orifices of the body to symbolise its specially vulnerable points. Matter issuing from them is marginal stuff of the most obvious kind. Spittle, blood, milk, urine, faeces or tears by simply issuing forth have traversed the boundary of the body.

(121)

body, particularly in the shape of sense organs, and fascinated with blood. Investing the text with these images gives the text human attributes, and it reinforces the idea that reading a Blake text means crossing bodily perime-ters. The power Douglas sees in this crossing provides a way to understand Blake’s prophetic purpose. Like the borders of social and other systems, Blake’s claim to transformation may be arbitrary. As he recognizes, there is always the possibility of failure; perhaps an encounter with his work will not produce enlightenment or improvement, or even comprehension. By dramatizing the taboos of the body’s limits, especially when he often depicts bodies as not final in their form but metamorphosing and splitting, Blake acknowledges this arbitrariness, but also borrows the power invested in borders. By recreating the body in textual form, and encouraging the reader to cross its borders as well as depicting border crossing within the text, Blake demonstrates that the shape of the body as we know it is not absolute. This makes possible a vision of a transformed body. Not only can the human form exceed its present potentialities, but anything the body can stand for – according to Douglas, any system of society or ideas – thus can also potentially be transformed.

audience, even if not attentive, ‘shall know that there hath been a prophet among them’. Additionally, the danger (even if imaginary) of such a rite of initiation helps ensure that those unfit to receive the transformative power of Blake’s prophetic books will fail, as unfit initiates will purportedly ‘die from hardship or fright, or by supernatural punishment for their misdeeds’ (Douglas 96).

Julia Kristeva takes Douglas’ anthropological observations and applies them to the individual psyche, and to writing. In Revolution in Poetic Lan-guage, through her theory of the semiotic and the symbolic, she considers disruptions of the system of language, while in Powers of Horror: an Essay on Abjection, Kristeva confronts threats to the borders of personal identity. To build her theory of the semiotic and the symbolic, Kristeva begins with ideas from Lacan: that the child is originally one with its mother and only later realizes its separate identity. A separate identity is a condition of being able to use language: one needs a position from which to speak, and an under-standing of the existence of objects to be able to form a statement. Kristeva imagines the characteristics of that pre-linguistic state, as far as they can be imagined. She calls that state the semiotic chora, and explains, ‘the drives, which are “energy” charges as well as “psychical” marks, articulate what we call a chora: a nonexpressive totality formed by the drives and their stases in a motility that is as full of movement as it is regulated’ (Revolution25). It is ‘nonexpressive’, being pre-linguistic, yet it is not totally without structure. It is ‘regulated’; the mother’s body (around which the child’s drives are oriented) gives it order (27). Kristeva argues that:

the chorais not yet a position that represents something for someone (i.e. it is not a sign); nor is it a positionthat represents someone for another position (i.e. it is not yet a signifier either); it is, however, generated in order to attain to this signifying position. Neither model nor copy, the choraprecedes and underlies figuration and thus specularization, and is analogous only to vocal or kinetic rhythm.

(26)

The semiotic, then, is associated with drives and rhythm, and is a basis for proceeding to independent identity and the use of language. Since it is a basis for language, it continues to exist and occasionally show itself in lan-guage. The semiotic underlies, and as drives is perhaps the impulse or fuel that powers symbolic language, which in turn is associated with order and meaning. To proceed from the semiotic to the symbolic a child must master the thetic: being able to have a thesis, make a judgment, take a position in relation to an object.

brings about all the various transformations of the signifying practice that are called ‘creation.’ Whether in the realm of metalanguage (mathemat-ics, for example) or literature, what remodels the symbolic order is always the influx of the semiotic. This is particularly evident in poetic language since, for there to be a transgression of the symbolic, there must be an irruption of drives in the universal signifying order, that of ‘natural’ language which binds together the social unit.

(62)

Being concerned with music as well as meaning, poetic language is a suit-able place to find eruptions of the symbolic, of drives, of speaking to express an urge. When looking at texts, Kristeva denotes as ‘genotext’ passages which ‘include semiotic processes but also the advent of the symbolic’; the ‘drive energy’ they hold can be detected, for instance, in ‘the accumulation and repetition of phonemes or rhyme’ as well as ‘melodic devices (such as intonation or rhythm)’ (86). What she calls the ‘phenotext’ shows symbolic language: ‘language which serves to communicate’, which ‘obeys rules of communication and presupposes a subject of enunciation and an addressee’ (87). Kristeva argues that ‘the signifying process . . . includes both the geno-text and the phenogeno-text; indeed it could not do otherwise’ (87–8). However, ‘every signifying practice does not encompass the infinite totality of that process’ (88). That is, the semiotic and symbolic are both involved in all writing, and each are revealed to a greater or lesser extent in genotext and phenotext. In much writing the phenotext dominates because of socio-political constraints that make the signifying process fixed, that ‘obliterate the infinity of the process’ (88). Kristeva insists that the semiotic is a process, and reading texts which reveal the influence of the semiotic (an example she gives is James Joyce) ‘means giving up the lexical, syntactic, and seman-tic operation of deciphering, and instead retracing the path of their pro-duction’ (103). Kristeva uses words which emphasize the transgression involved in the semiotic disrupting the symbolic. Though the symbolic relies on the semiotic, it is ‘torn’ by it. Like the wilderness that lies outside of Douglas’ systems, the semiotic is a powerful threat to the symbolic, and writers who tap into it harness its power, yet not without risk of the sym-bolic being wholly ‘torn’. If there is ‘an attempt to hypostasize semiotic motility as autonomous from the thetic – capable of doing without it or unaware of it’, that is, if the play of the semiotic is pursued so far that the writer no longer has a position to speak from nor any concept of a listener, then a ‘text as signifying practice’ will no longer be a text but fall into the category of ‘drifting-into-non-sense’, the babble of madness (50–1).

inscribed within the phenotext the plural, heterogenous, and contradictory process of signification, encompassing the flow of drives, material disconti-nuity, political struggle, and the pulverization of language’ (88). Blake lived in a revolutionary period and seemed to many to be teetering on the edge of madness. Few readers of Blake have considered how Kristeva’s theory of the semiotic and symbolic might shed light on his work, but Thomas Vogler finds the semiotic operating in Miltonwhere Blake puts symbolic language on hold to transcribe a lark singing ‘trill, trill, trill, trill’. Vogler argues, ‘the “high ton’d Song” of the “loud voic’d Bard” gives way to “this little Bird”, whose trill, though not “words”, may concern our “eternal salvation” ’ (146). There is a hint here of the redemptive capacity of the disruption of language. Vogler also notes the similarity between Blake’s description of Beulah and Kristeva’s concept of the chora: ‘As the beloved infant in his mothers bosom round incircled / With arms of love & pity & sweet compassion’ (Vogler 144, M 30:10–12); ‘Infant Joy’ also shows Blake’s interest in the infant time before, and transition to, expression and identity. Much earlier than Vogler, Swinburne, making an admirable effort to describe the character of Blake’s prophetic books, finds in them something similar to the music of the semi-otic. Notably, he places his observation in the realm of child development: ‘Blake was often taken off his feet by the strong currents of fancy, and indulged, like a child during its first humour of invention, in wild byplay and erratic excess of simple sound’ (194). He detects not just this impulse, but also a contrary one existing alongside it. ‘At one time we have mere music, chains of ringing names, scattered jewels of sound without a thread, tortuous network of harmonies without a clue; and again we have passages, not always unworthy of an Æschylean chorus, full of fate and fear; words that are strained wellnigh in sunder by strong significance and earnest passion’ (Swinburne 195). For Swinburne, at times, Blake’s verse collapses under meaninglessness; at others, under excess of meaning.

Wilkinson recognizes the threat to sanity inherent in mixing message with openness, and his description echoes Kristeva’s idea that a revolutionary poetic text is not fully symbolic, or sane, or communicative, but rather is disrupted, or obscured, by the phantasies of the semiotic. Kristeva’s empha-sis on signification as a process can also be related to Blake’s apparent reluc-tance to give final form to a text. He uses his control over every stage of the process in making his illuminated books to ensure that no two copies are the same, and he takes advantage of his license to make changes during the production of his work in a continuous creation rather than a mere reproduction. Blake draws attention to the process of the work’s making to emphasize that it is not final, not written in stone. Yet, it is written in metal, almost as solid as stone; to that extent it is ‘fixed’ like Kristeva’s symbolic, but Blake’s process, his self-awareness of that process, and the steps he takes to remind the reader of it, mitigate and disrupt that fixity.

of bodily existence is not a move to reject the body, but rather a step in the process of transforming the body.

To explicate the concept of abjection, Kristeva begins with ‘food loathing’ which she argues ‘is perhaps the most elementary and most archaic form of abjection’. Kristeva describes reactions of physical disgust to ‘that skin on the surface of milk’. Milk is, of course, a bodily fluid, one of those things that crosses bodily borders; it is involved in a repeated Biblical prohibi-tion, ‘thou shalt not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk’ (Exod. 23:19, 34:26, Deut. 14:21). The milk skin Kristeva focuses on also shows signs of category-crossing. Contradicting milk’s liquidity, its skin is somewhere in the viscous area between solid and liquid, that slimy territory often found disgusting, perhaps because of other bodily fluids which are thick and can harden, such as blood and mucus. Kristeva writes, from the point of view of the child reacting to its parents’ offer of milk,

‘I’ want none of that element, sign of their desire; ‘I’ do not want to listen, ‘I’ do not assimilate it, ‘I’ expel it. But since the food is not an ‘other’ for ‘me,’ who am only in their desire, I expel myself, I spit myselfout, I abject myself within the same motion through which ‘I’ claim to establish myself.

(3)

The problem is, what is rejected in order to define the self is really part of the self: here, nourishment. Kristeva pictures a body, an identity that is not permanently defined. Abjection is about deciding, labelling what is ‘me’ and what is ‘not me’, but as Kristeva says, this time considering the corpse as an example of the abject, ‘it is something rejected from which one does not part, from which one does not protect oneself as from an object’ (4). Like the nourishment that builds the body, rejecting it means rejecting the self. With the body, this is inevitable: one day, in death, it will be ‘not me’. The abject, like Douglas’ abomination, is caused not by ‘lack of cleanliness or health . . . but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite’ (Kristeva, Horror 4).

by ritual’ (135–6). This view is in line with her anthropological perspec-tive: she is concerned with whole societies, their functioning and self-preservation. Kristeva, as an analyst, focuses more on the individual psyche; not only that, but on the malfunctioning psyche which does not necessar-ily have any care for gaining moral approval or aiding the smooth func-tioning of society, and so she finds the apex of abjection in amorality. ‘The traitor, the liar, the criminal with a good conscience, the shameless rapist, the killer who claims he is a saviour. . . . Any crime, because it draws atten-tion to the fragility of the law, is abject, but premeditated crime, cunning murder, hypocritical revenge are even more so because they highten the display of such fragility’ (4). Jerusalem’s plate 3 could be an example of abjec-tion. Blake has perpetrated premeditated violence upon his ‘human’ cre-ation. Granted, it is not as dire a crime as assault on an actual human being, but Blake is using his text to symbolize the human body, to avail himself of the powers of that ultimate symbol. In plate 3 he also approaches his audi-ence with abjection: he is addressing us (‘To the Public’), confusing us (with fractured sentences) and insulting us (by refusing to call us ‘Friend’) all at once. It is a friendly overture, marred, and left contradictory, reaching out and pulling back, rejecting but not fully able to reject.

Jerome McGann observes, in Toward a Literature of Knowledge, Blake’s gouging of letters from ‘To the Public’ without replacing them with any-thing causes ‘not simply a set of awkward transitions and distracting blank spaces’ but ‘positive incoherence’ (10). McGann argues that since Blake worked on Jerusalemfor

at least ten years . . . he might have changed plate 3, given it some kind of verbal coherence. But he preserved a scarred discourse as the opening of his text, so that plate 3 must be regarded as what textual scholars some-times call ‘the author’s final intentions’.

(Knowledge 10)

passages in Jerusalemhe cannot restore (Erdman, ‘Suppressed’ 2–4). The lines are not there. Filling them in means reading another page. Yet, as it stands, the page could be called unreadable. We are not presented with the copper plates as reading material, but read the printed page embellished with water-colour and pen and ink. Still, Blake does not let the reader forget the process which created the page. Erdman sees that ‘a vigorous gouging could level these surfaces beyond recovery . . . but in many instances Blake did not carry his negating beyond a few strokes, leaving a stubble of metal that would print broken outlines of letters and ghosts of words’ (‘Suppressed’ 2). The process of the creation, and the destruction of the page, is made visible in the scars from the gouging. They are nonverbal elements which seem to require interpretation, because without explaining them the sentences they affect are unreadable. Interpretation most often follows two roads, one toward reconstruction and one toward motivation, but both go back to the making of the page: what did it say before, or what caused these deletions to be made?

Joseph Viscomi finds that Blake deletes ‘words that connote connec-tion, even at the cost of rendering [sentences] meaningless’. He guesses that ‘the deletions almost certainly were made after Blake’s failed exhibition and estrangement from Cromek, Stothard, and possibly even Butts. It appears to have been especially disturbing to Blake to have his works owned by people he no longer liked or trusted’ (339). Though this might seem to be an exces-sive desire for control over his audience – a desire for control which works against the desire to be heard – it is understandable, considering the time and care required by Blake’s handmade illuminated books, as well as their personal character as compared to the work that Blake did for commeri-cal purposes. There is also Blake’s prophetic purpose. Viscomi turns this spiritual aspect invested in Blake’s illuminated books into an intriguing explanation:

Ideally, the study of art is analogous to the study of Christ; the student, disciple or reader undergoes a transformation or conversion; one comes to perceive self and world differently. In this sense, Blake’s audience was select, but also made select through reading and owning Blake’s works. The problem is that bad people sometimes own good work, which is as troubling as Job’s undeserved afflictions. In both cases self-defining beliefs, whether about God’s existence or goodness, the value and power of one’s own work, or the meaning of imagination, can be cast in doubt. (339)

uninitiated, and it does keep Blake’s later works secret from most who have not proceeded to the cloister of postgraduate study. Blake himself professes a belief in exclusive understanding, when he counters Dr Trusler’s criticisms of his otherworldly art:

You say that I want somebody to Elucidate my Ideas. But you ought to know that What is Grand is necessarily obscure to Weak men. That which can be made Explicit to the Idiot is not worth my care. The wisest of the Ancients considerd what is not too Explicit as the fittest for Instruction because it rouzes the faculties to act.

(E 702)

Blake is not creating his works for the weak, or for idiots, but rather for those willing to be roused. Being ‘not too Explicit’ is an essential strategy for his illuminating purpose – it is ‘fittest for Instruction’ – and it also aids him in making sure that his audience will be, as Viscomi calls it, ‘select’.

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the prophetic purpose of Blake’s engrav-ing is explicitly linked to the body. On plate 14 Blake predicts ‘the whole creation will be consumed, and appear infinite and holy whereas it now appears finite & corrupt’. This transformation of the body of creation will not arise from denial of the human body but rather ‘an improvement of sensual enjoyment’. Blake has a part in bringing about this apocalypse: ‘But first the notion that man has a body distinct from his soul, is to be expunged; this I shall do, by printing in the infernal method, by corrosives, which in Hell are salutary and medicinal, melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid’ (14:6–16). Blake claims for himself and his printing the ability to spark this transformation. His illu-minated book argues for the unity of soul and body; it also demonstrates it. The illuminated books depend on their medium, their physical form or body. If they are reincarnated in another form, for instance ordinary type-face, part of their being is left behind: they are no longer the same. The intertwining between word and image parallels, or even dramatizes, the mutual dependence in Blake’s works between content and form, soul and body. Content could be called soul, infusing and giving life and meaning to the body of the text, and form could be called body, giving shape to other-wise amorphous ideas. However, since they are so interdependent it is dif-ficult to consider final a parallel which assumes the body is a mere container for the soul. For Blake, between the body and the soul, which gives form and which gives meaning? The parallel seems to hold in the fallen world, where bodies serve to save from nonentity; their limitations are lesser evils than entire shapelessness. But as we will see, considering Blake’s belief in physiognomy, and his ideal of a transparent body like a transparent garment which reveals rather than covers, perhaps it is the soul which provides the true form. And, since Blake idealizes the Human Form Divine, and holds that conception and execution are inseparable,3 how could the body not participate in providing meaning?

deserts between the furrows of letters’ (91). As for Marriage14, leaves grow from ‘sensual enjoyment’, and a horse gallops in a blue space as if about to leap the ‘-finite’ which comes at the end of the famed assertion, ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infi-nite’ (14:17–19). At the top of the plate, a male figure lies flat, and a female hovers above him, arms spread; flames envelop them both. These figures epitomize the process of revelation through cleansing with ‘salutary and medicinal’ corrosives; they also illustrate the identity of Blake’s plates as living things. The editors note that the design ‘plays on those metaphors’ in the text of ‘the consumption of the world by fire at the Last Judgment and the consumption of copper by acid’ (136); in fact, it personifies them. The world and plate consumed by fire are embodied by the recumbent figure: they have a human form. The fire that reveals the infinite is pictured as female. She, like the later emanation and the biblical Wisdom, is an element aiding in the creation of the world and the work of art. Also like the emanation and Wisdom, she is an aspect of the human or of God who only appears to have separate being. In reality, they are one. In reality, the process of creation is part of the text, pictured in it, embodied in it. The design, as the editors note, recalls ‘the conventional iconography of soul and body’, used by Blake in such works as his illustrations to Blair’s Grave (136). The plate, then, also reflects the relationship of soul and body explained earlier in the Marriage: ‘that calld Body is a portion of Soul dis-cernd by the five Senses’ (4:14–15). If the female soul is part of the engrav-ing process, then it is createngrav-ing through corrosion a body which reveals the infinite which was hid, the ideas and images which would otherwise remain hidden in the artist’s mind.

The engraving metaphors in The Marriage of Heaven and Hellshow that Blake’s self-conscious figuration of his texts within themselves extends to seeing his text as human. Just as ‘the Bible of Hell’ mentioned in Marriage 24 could refer not only to the text at hand, but to Blake’s view of his whole project of illuminated printing, so can the humanization of his works. David Erdman suggests that Los’s ‘numerous sons’ who ‘shook their bright fiery wings’ (or pages) in Europe 5[6] could be Blake’s illuminated books personified (in Tolley 127). Elsewhere, descriptions of Los and Enitharmon embodying their children can be parallelled to William and Catherine Blake creating illuminated books. As Essick argues, Los is a blacksmith, working in metal as Blake works with his metal engraving plates; he provides the form while Enitharmon provides the colour, as Catherine would help in the watercolour finishing (‘Female Will’ 620). A passage Essick offers as an example of this imagery makes clear the birthlike nature of this collaboration:

And Enitharmon like a faint rainbow waved before him Filling with Fibres from his loins which reddend with desire Into a Globe of blood beneath his bosom.

(J86:48–52)

There is, then, a sexual element to this creation, the books being sons and daughters of their co-creators or parents. Also in Europethere is a catalogue of sons and daughters of Los, some rarely seen again, like Manathu-Vorcyon, and some prominent characters in Blake’s myth, like Orc. There is a sugges-tion of a sprawling mythology. Each person in the lineage has a story and some of these stories are preserved in books while others remain mysterious. Oothoon, for instance, has her story told in five lines of description in Europe, but Visions of the Daughters of Albionis her own whole book. If this is true of Oothoon, then the other children also, here only abstracts, could elsewhere be whole books. It is as though books, as well as characters, are ‘offspring’ of each other.4Vincent De Luca suggests another way in which the relationship between Enitharmon and her children is defined textually: they are born from her name. Their names – Oothoon, Theotormon, et cetera – ‘derive, anagrammatically or through slight phonetic shifts and condensations, por-tions of their own literal being’ from their mother’s name (97).

Open to joy and to delight where ever beauty appears If in the morning sun I find it; there my eyes are fix’d In happy copulation.

(9:22–10:1 and note)

Beauty appears in the pages of the prophecy and the reader as perceiver is, by Oothoon’s definition of perception, copulating with the book. In return the book is also ‘screwing with your head’: if the reader accepts Oothoon’s suggestions, his or her view of sex and perception may be transformed. It could be a mutual, liberating and jealousy-free relationship as envisioned in the text. However, since Oothoon is a character from a psychological drama, it is difficult to know whether her view of things is to be so thoroughly embraced, or whether she is going too far: is she an ideal, or just a mental state? If Blake desires such abandon in participation in his texts, does he believe it is even possible? And if so, would Blake want everyone to become that intimate with his children? Can he gain any control over who does and who does not?

general public, and treated by collectors like a work of art: displayed in the home for the owners and their visitors. To see the work, one would have to see an original.

Now, though, with the Blake Trust editions, and the Blake Archive, Blake’s children are becoming more promiscuous, which by Oothoon’s lights may be good. The Archive allows exciting manipulation of the images in a kind of cyber-sex perception which, ironically, allows one to handle the works more intimately while not providing any ‘real’ contact with them, only virtual. The Blake Trust editions are rich in colour and detail, and their copious and enthusiastic notes can provide an experience almost like an ini-tiation – both overwhelming and enlightening – into the exclusive circle of Antients or Blakean friends familiar with the originals. However, if reading a translation is like kissing through a handkerchief, seeing Blake’s works in reproduction, even an excellent one, is likewise.5The online Archive turns Blake’s works into light rather than texture, and the Blake Trust editions turn them to plain paper, again rather than texture. A reader cannot perceive the imprint of the plate’s pressure, or the thickness or thinness of ink and paint, or the inimitable substance and sparkle of gold leaf. Even with the privilege of seeing the originals, one must not touch works of art; still, the texture can be better perceived visually on the originals.

it with a negative kind of secret knowledge, one used to preserve traditional, hierarchical systems of thought and belief – and to enact repressed sexual-ity – rather than rousing the faculties. Yet if full-body embraces are com-minglings, then the skin through contact is not just touching but somehow melding. The skin becomes an orifice. Applying this to the skin of the book, it is a surface with openings (painfully obvious in Jerusalem’s ‘To the Public’), not just one but many places for the reader to penetrate and commingle with the text in participatory perception.

at the end of Jerusalem, conversing through ‘Visionary forms dramatic’ (98:28).

The frontispiece of Jerusalem, Blake’s final prophecy, suggests that the reader should enter the book. It depicts a figure entering a Gothic door with darkness behind, carrying a light-giving globe. The figure looks around, as though entering with some trepidation. That this is a spiritual journey is suggested by the soul-like sphere, and its introduction of light into dark-ness. Ironically, though, it is usually the book that enlightens: here, it seems, the pilgrim must carry his own enlightenment, or be lost. Unlike another archway in another spiritual epic (‘Abandon hope, all ye who enter here’), this one does not offer any (even despairing) verbal advice, again suggest-ing that he who enters is on his own. In an earlier version of the plate there were words written above and around the entry; as in ‘To the Public’ Blake takes away what might have eased interpretation for the reader. The obscured words include a line which indicates that Los ‘enterd the Door of Death for Albions sake’ (130). Like Dante’s, this is an entry into the world of the dead. While Dante’s inferno is a terrain which culminates in the body of the devil as a place to be tortured, for Blake the body plays a greater role in shaping the geography of hell. Another epigram reads,

There is a Void outside of Existence, which if enterd into Englobes itself & becomes a Womb, such was Albions Couch A pleasant Shadow of Repose calld Albions lovely Land

(130)

The figure suggested to be Los enters the door of death, also a void which becomes a womb, also Albion’s resting place for his repeated death and dying in this book, also Albion as Blake’s mythological England. These lines link to others within the poem:

Los took his globe of fire to search the interiors of Albion’s Bosom. in all the terrors of friendship. entering the caves Of despair & death.

(31[45]:3–5)

death for a friend’s sake, as well as an intimacy comparable to sexual inti-macy, might be more than a reader is willing to give. But, as the Jerusalem frontispiece suggests, Blake seems to expect a reader to come prepared, car-rying his or her soul, or be expelled by the darkness of the text.

These possibilities of a reader’s reluctance and expulsion arise in The Book of Thel, which faces the failure of poetry’s transforming power and also, as we shall see, considers the failure of human embodiment. Thel is in need of comfort because of a sense of purposelessness in life. She considers and rejects a range of advice from the inhabitants of her valley, advice which predominantly recommends giving of oneself: being eaten like the Lilly and dissolving like the Cloud. Like Los on the Jerusalemfrontispiece, she takes an underworld journey. The matron Clay addresses her:

I heard thy sighs. And all thy moans flew o’er my roof. but I have call’d them down: Wilt thou O Queen enter my house, ‘tis given thee to enter. And to return; fear nothing. enter with thy virgin feet.

(7:14–17)

such questions. Compared to Jerusalem3, this is a different kind of fill-in-the-blanks, more accommodating to the reader, but it is still an erasure which is obvious and makes one wonder what was there. The visible dele-tion of the offending lines is like a dramatizadele-tion of the rejecdele-tion of per-meability in the poem, but it results in a space in the text that, as we have seen, is like an orifice. The Book of Thel, whose heroine Helen Bruder has found to evoke judgmental reactions of disgust from some readers and admiring feelings of liberation from others (Bruder 40, 45, 53, 200), func-tions like Dörrbecker says Europe does. It does not impose a particular reading but places the onus of interpretation on the reader in a way that forces the reader to confront his or her own desires for the text. Leaving those two lines blank, then, is like letting the reader fill in his or her own ultimate questions. The blankness may be motivated by concern for reader ‘sensibilities’, providing the option to leave penetrating questions repressed; however, this open text is not totally open. As syntax in ‘To the Public’ narrows the possibilities for what could appear in the spaces, here the gist of the list of questions leaves only so much leeway as to how to fill in the blanks: whatever it is, it must be a question about sense organs and the body’s vulnerable borders.

After these questions, ‘The Virgin started from her seat, & with a shriek. / Fled back unhinderd till she came into the vales of Har’ (8:21–2). She rejects the body, and she rejects the body of the text – the kind of body Blake’s text claims to be – a permeable one, hellish and dangerous. Understandably, she is reluctant to make herself vulnerable in the ways enumerated in the sense catalogue, ambivalent about possibly being devoured or dissolved in communication. William Godwin recognizes this fear and treats it even-handedly, in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice:

Every man that receives an impression from any external object has the current of his own thoughts modified by force; and yet without external impressions we should be nothing. We ought not, except under certain limitations, to endeavour to free ourselves from their approach. Every man that reads the composition of another, suffers the succession of his ideas to be in a considerable degree under the direction of his author. But it does not seem as if this would ever form a sufficent objection against reading. One man will always have stored up reflections and facts that another wants. . . . Conversation is a species of co-operation, one or the other party always yielding to have his ideas guided by the other: and yet conversation and the intercourse of mind with mind seem to be the most fertile sources of improvement.

(452)

the word ‘conversation’ for both (in Fleetwood for example [265]). Here, conversation is fertile intercourse. But how does one, as Godwin sets out to do here, ‘mark the limits of individuality’? Given such influence – given Thel’s worries about the orifices through which the outside floods in – is it possible?

2

Graphic Bodies

The colour print Elohim Creating Adam (Figure 2.1) is a visual statement about the human body at its creation. It reveals much about Blake’s opinion of the created body and contains many of his most puzzling graphic idio-syncrasies. Striking aspects of the picture include the inattentive violence with which the Elohim pushes back Adam’s head to a painful angle. The faces seem to reflect each other but are not exactly mirror images. Similarly, the two bodies are almost horizontally symmetrical: the chests are close while the rest of their bodies curve outward. In the perfectly round semi-sun hidden by the action, the straight rays and shapely clouds separated by the bodies from the rugged, sloppy ground and water at the base, careful geometry and dubious mistakes, order and chaos, strangely coexist.

Christopher Heppner, in Reading Blake’s Designs, lists difficulties in Blake’s depiction of these human forms (52). The Elohim’s body has no middle: his shoulders are almost directly connected to his hips, with nothing in between but the locks of his long beard and the impractical tendons which attach the shoulders to the wings. These wings, according to Heppner, are neither aerodynamic nor modelled on the wings of any flying creature. Heppner suspects that Adam has suffered a severe beating; his ankle and wrist seem broken, or ‘re-attached by a careless surgeon after an accidental amputation’ (52). Heppner argues that these apparent mistakes invite interpretation; when such features appear in the works of Blake or any artist, ‘we would attempt to understand just why the body showed such a dislocation’ (52).

For all its deformity and pain, Elohim Creating Adamis a powerful picture; grace accompanies this oddly violent act. The malfunctioning wings are beautifully patterned. The muscles and bones are indicated with loving del-icacy, though incorrect, suggesting a passion for the human form, while its creation is depicted as a cosmic tragedy. Anne Mellor perceives a love-hate relationship with the body pervading Blake’s work, particularly in the Tate Gallery colour prints, of which Elohim Creating Adamis one. She writes that this series ‘reflects Blake’s philosophical condemnation of the human form. But this very condemnation is presented in visual terms that glorify the

human form: the figures in the Tate Gallery series are uniformly large, mus-cular and heroic’ (Divine 103). Beyond the Tate prints, Mellor notices that Blake’s designs generally ‘are composed almost without exception around a distinctly outlined human figure’. She sees Jerusalem as a representative example of this and claims, ‘The visual world of Jerusalem, then, is the human form: here the human body creates its own pictorial space, its own compositional relationships’ (Divine 286–7). If Blake’s illuminated books are human forms, they are also organized around the human form at once despised and glorified, and made so as to show this full spectrum of bodily existence.