Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:28

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Online Course Delivery: An Empirical Investigation

of Factors Affecting Student Satisfaction

Mirjeta S. Beqiri , Nancy M. Chase & Atena Bishka

To cite this article: Mirjeta S. Beqiri , Nancy M. Chase & Atena Bishka (2009) Online Course Delivery: An Empirical Investigation of Factors Affecting Student Satisfaction, Journal of Education for Business, 85:2, 95-100, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903258527

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903258527

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 280

View related articles

CopyrightC Heldref Publications ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903258527

Online Course Delivery: An Empirical Investigation

of Factors Affecting Student Satisfaction

Mirjeta S. Beqiri and Nancy M. Chase

Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington, USA

Atena Bishka

TD Bank Financial Group, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

The authors investigated potential factors impacting students’ satisfaction with online course delivery using business students as participants. The findings suggest that the student who would be more satisfied with the delivery of online courses fits the following profile: graduate, married, resides more than 1 mile away from campus, and male. Other factors found to influence student satisfaction include the appropriateness of the course being offered online and the degree of familiarity with it. Lastly, the study provides insights into students’ attitudes toward the blended course delivery mode.

Keywords: Academic status, Distance learning, Online, Sociodemographic factors, Student satisfaction

Whether at the undergraduate or graduate levels, studying for a business administration degree has traditionally been a means of attaining an initial professional position in the workplace, improving employment opportunities, or further-ing an existfurther-ing career. Recent statistics indicate that durfurther-ing the 2005–2006 academic year in the United States, more than 318,000 individuals received undergraduate business degrees and more than 146,000 individuals earned a master’s degree in business. Compared with the undergraduate and graduate business degrees granted during the 2000–2001 academic year, these numbers represent an increase by 20.7% and 26.6%, respectively (National Center for Education Statis-tics, 2007).

At the graduate level, attaining a master of business ad-ministration (MBA) degree has been a means of career de-velopment for individuals interested in acquiring manage-ment skills and improving job opportunities (e.g., Eberhardt, Moser, & McGee, 1997; Sturges, Simpson, & Altman, 2003; Zhao, Truell, Alexander, & Hill, 2006). The MBA degree is thus “generally regarded as a competitive advantage for enhancing one’s business career” (Huang & Chuan, 2005, p. 203). On the other hand, undergraduate business students have a variety of choices upon graduation, including (a)

Correspondence should be addressed to Mirjeta Beqiri, Gonzaga Uni-versity, School of Business Administration, 502 E Boone Ave, AD Box 9, Spokane, WA 99258, USA. E-mail: beqiri@jepson.gonzaga.edu

pursuing full-time employment, (b) attending a graduate-level degree, or (c) utilizing a combination of employment and graduate studies (Piotrowski & Cox, 2004). Under-graduate business students entering the job market upon graduation indicate they have “high expectations of find-ing employment in their chosen field or specialty area. Most plan to be earning a respectable income in their initial job” (Piotrowski & Cox, 2004, p. 716).

McFarland and Hamilton (winter 2005/2006) offered a variety of definitions for the notion of online courses. These ranged from “a course having materials delivered online that meets synchronously and regularly. . .” to “a course having materials delivered online that never meets synchronously, and the student learns completely independent of a live in-structor” (p. 25). For purposes of the present study,online

courses refer to courses in which materials are delivered

entirely online, and students have access to the instruc-tor only electronically. Therefore, no face-to-face interac-tion occurs in such courses. Another contemporary course delivery method, referred to as blended, requires that stu-dents meet face to face with the professor for several ses-sions of the course; however, the majority of sesses-sions are asynchronous. Additionally, because distance learning also refers to courses delivered electronically through Web-based sources (McLaren, 2004), we use the terms online instruc-tion and distance learning interchangeably throughout this article.

96 M. S. BEQIRI ET AL.

Distance learning has been practiced in a multitude of forms since the early 1990s (Campbell, Floyd, & Sheridan, 2002). Both student and faculty interest in distance learn-ing has continued to increase as technology improves and fully supports this mode of course delivery (e.g., Alstete & Beutell, 2004; McFarland & Hamilton, winter 2005/2006; Tabatabaei, Schrottner, & Reichgelt, 2006). Although the number of online business courses offered at many universi-ties is increasing, the perception of the value of online degrees has remained somewhat negative (Alsop, 2004), and “the tra-ditional full-time degree still rules with corporate recruiters” (p. 2).

BUSINESS STUDENT POPULATIONS

The majority of undergraduate business students enter the higher education environment directly upon graduation from high school. However, increasing numbers of nontraditional students are also enrolled in undergraduate programs. The

nontraditional student has been defined as one who holds

“a full-time job, who has little flexibility in his or her daily schedule” (Medlin, Vannoy, & Dave, 2004, p. 429).

According to Alstete and Beutell (2004), certain “demo-graphics were found to be more influential than other factors in predicting the interest of potential students in online busi-ness education, particularly the student age, annual income and employment status” (p. 6). Other student populations that might benefit from online courses included those with scheduling conflicts from work, athletics, or other classes, as well as students suffering from injuries or illness that would prevent them from attending a traditional class (Boose, 2001). Graduate business students differed from their undergrad-uate counterparts in several significant ways. The typical graduate student was likely to be older, female, and diverse in terms of race and nationality (Friga, Bettis, & Sullivan, 2003). Many graduate students were working professionals who brought relevant work experience and insight into the classroom (e.g., Ebersole, 2004; Giacalone, 1998; Richards-Wilson, 2002). Gosling and Mintzberg (2004) suggested that “providing education in the context of deep-rooted practical experience turns the classroom into a rich arena for learning” (p. 19). Working professionals tend to be more confident as a result of their functional business experience and they are frequently willing to express their opinions. Sometimes, these students have competencies “that eclipse those of the instructor. In such instances, they can become valuable re-sources with the potential to contribute in a most meaningful manner to the effectiveness of the course” (Lazer & Frayer, 2000, p. 7). Graduate business students can also be very vocal and demanding; they often have higher expectations than do regular students (e.g., Lazer & Frayer, 2000; Rapert, Smith, Velliquette, & Garretson, 2004). On the other hand, segments of the graduate student population comprise young adults with little managerial experience (Armstrong, 2005).

Frequently, these students enter the master’s program upon completion of the undergraduate degree and therefore have minimal first-hand business experience.

Distance Learning and Online Instruction

Online course offerings in higher education have continued to steadily increase over the past decade (Bocchi, Eastman, & Swift, 2004; Campbell et al., 2002). Graduate students and working professionals are likely to be attracted to those busi-ness schools offering the flexibility of ubiquitous and just-in-time distance learning courses, which enable students to re-main in the workplace and to be productive for the employer. At the same time, the employee obtains the “desired skill set while keeping a needed income producing job” (Hollenbeck, Zinkhan, & French, 2006, p. 41). One of the by-products of online courses is increased flexibility in the content delivery as well as in the learning process (Arbaugh, 2005).

Bocchi et al. (2004) maintained "that there is significant growth in the online market because students working full-time are the fastest growing segment of the student popu-lation and they bring corporate tuition dollars with them” (p. 245). Time management seems to be a major concern for this group because students are juggling commitments in terms of classes, work, and family (McEwen, 2001).

Distance learning has emerged as an alternative to the tra-ditional classroom mode of delivery (Lawrence, 2003) even for the quantitative courses (e.g., Brown & Kulikowich 2004; Grandzol, 2004). Teaching these courses online provides stu-dents with the flexibility to work and study at the same time, but it may also posit new challenges. Although the tradi-tional approach of teaching is instructor centered, distance learning is more student centered (Larson, 2002). Also, dis-tance learning could be a lonely experience (Desanctis & Sheppard, 1999). In the traditional classroom setting, al-though students may frequently struggle to solve a diffi-cult problem, they also enjoy access to immediate help from the instructor or peers. Should this situation occur during a distance learning course, the student may feel isolated or abandoned without immediate access to help or expertise (Desanctis & Sheppard, 1999), and may even withdraw from the course. Consequently, monitoring the design and the qual-ity of online courses becomes even more critical, and the as-sessment of students’ satisfaction with these courses equally essential.

METHOD

The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential factors affecting students’ satisfaction with online courses. The following research questions were addressed:

Research Question 1:Does students’ satisfaction with online

courses differ based on their sociodemographic status?

Research Question 2:What education-related factors impact students’ satisfaction with online courses?

Research Question 3: Is the students’ satisfaction different

for online compared to blended courses?

To answer these questions, we designed a questionnaire relying on the literature pertaining to online instruction as well as employing findings from a pilot study we previously conducted with business students. The earlier study identified potential factors impacting students’ interest and motivation in taking online courses. However, due to the small number of students involved in this pilot study, no statistical analyses were performed.

For the purposes of the present study, the survey was de-livered via the Internet to undergraduate and graduate busi-ness students pursuing busibusi-ness degrees at Gonzaga Uni-versity (GU), a private Jesuit uniUni-versity located in Spokane, Washington. The total number of students in the target pop-ulation was 962, of which 767 were undergraduates and 195 were graduates. To ensure a high participation rate among un-dergraduate students, the researchers collaborated with col-leagues (teaching at different academic levels) who agreed to grant extra course points for participation. Consequently, 509 undergraduate and all graduate business students en-rolled in the spring semester were invited to complete the survey. There were 168 responses collected from undergrad-uate students (a 33.0% response rate) and 72 responses col-lected from graduate students (a 36.9% response rate). All of the questionnaires received were usable resulting in a sample size of 240 respondents.

The web questionnaire consisted of three parts: the first section captured students’ sociodemographic profile, the sec-ond section solicited students’ perceptions about online and blended courses, and the last section, consisting of open-ended questions, asked students to share their own online experience. The data were collected by using Sawtooth Soft-ware SSI Web (Version 5.2.2) and subsequently uploaded into SPSS (Version 14.0). The qualitative variables were coded as follows: gender (0=female, 1=male), academic status (0=graduate, 1=undergraduate), major (1=business ad-ministration [BA], 2=accounting, 3=undeclared general business [UGB], 4=other), marital status (0=married, 1=

single), and distance from campus (0=less than 1 mile, 1=

more than 1 mile).

DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

This section outlines descriptive statistics regarding students’ profile and the distribution of variables of interest. To address the stated research questions, we performed various types of analyses, such as one-tailedttests, a paired samplesttest, an analysis of varianceFstatistic, simple linear regression, and multiple regression.

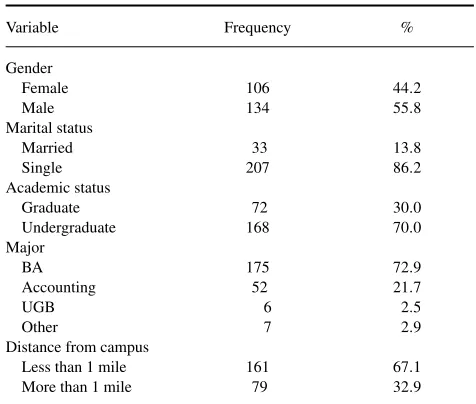

TABLE 1

Demographics of Participants (N=240)

Variable Frequency %

Undergraduate 168 70.0

Major

BA 175 72.9

Accounting 52 21.7

UGB 6 2.5

Other 7 2.9

Distance from campus

Less than 1 mile 161 67.1

More than 1 mile 79 32.9

Table 1 displays the respondents’ sociodemographic pro-file. Out of the 240 respondents, 134 were males and 106 fe-males. Most of these students were undergraduates (70.0%), majoring in business administration (72.9%), single (86.2%), and resided less than 1 mile away from campus (67.1%).

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for continuous variables. The average student was 23.33 years old(ranging from 18–62 years and a standard deviation of 6.75). To capture students’ perceptions about online courses, we included in the questionnaire such statements as “I like online courses,” “I think online courses are an appropriate way of learning in universities,” and “I would take a course online if I was, to some extent, familiar

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics for Continuous Variables (N=240)

Variable M SD

1. Age 23.33 6.75

2. I like online courses. 2.68 0.97

3. I think online courses are an appropriate way of learning in universities.

2.76 0.99

4. I would take a course online if I was, to some extent, familiar with the course material.

2.03 0.99

5. How many business courses have you taken online at GU?

2.08 0.93

6. How many blended business courses have you taken at GU?

1.29 0.75

7. How satisfied were you with the courses offered online?

1.74 0.81

8. How satisfied were you with the blended courses? 2.89 0.53

Note.Statements 2, 3, and 4 were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Statements 7 and 8 were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

98 M. S. BEQIRI ET AL.

with the course material.” These statements were measured using a five point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly dis-agree) to 5 (strongly dis-agree).

Furthermore, to separately assess students’ degree of satis-faction with online and blended courses, two questions were used: “How satisfied were you with the courses offered on-line (100% Internet)” and “How satisfied were you with the blended courses (both classroom and Internet based).” Both of these questions were measured using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly dissatisfied) to 5 (strongly satisfied). Lastly, the number of online and blended courses taken at GU by participants was recorded; the means were 2.08 and 1.29, respectively, and the standard deviations 0.93 and 0.75. It is important to stress that online and blended busi-ness courses at GU are offered only during summer in order to alleviate student scheduling conflicts, remove the need to commute to campus, provide students with the opportunity of a balanced workload spread throughout the academic year, and, in some cases, finish the degree as planned.

Sociodemographic Factors

To explore the differences on students’ satisfaction with on-line courses by sociodemographic status, several one-tailed t tests were performed. With regard to gender, male stu-dents (M = 1.81, SD = 0.83) reported a higher score of the Mean Satisfaction with Online Courses (MSOC) than did female students (M =1.65, SD=0.77). However, the difference was marginally significant, t(238) =1.55, p =

.06 (one tailed). Moreover, the results suggested that mar-ried respondents were significantly more satisfied with the online courses (M=2.48, SD=0.76) compared with single ones (M =1.62,SD=0.75),t(238)=6.11,p=.000 (one tailed). Furthermore, when considering the variable that cap-tured the distance the student must travel to campus, the data indicated that students living more than 1 mile away from campus (residing off campus) were more satisfied with the online courses (M=2.24,SD=0.90) than were those who lived close to or on campus (M=1.50,SD=0.63). The re-sults were found to be highly significant, t(238)=7.42,p=

.000 (one tailed). Lastly, graduate students reported that they were more satisfied with the delivery of online courses (M=

2.54, SD =0.84) than were undergraduate students (M =

1.40,SD=0.49),t(238)=13.18,p=.000 (one tailed). Ta-ble 3 summarizes the findings with regard to the comparison of means.

To determine whether or not there were any significant differences in MSOC by major we performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA), which indicated that there were no significant differences across majors,F(3, 236)=0.84,p=

.472. Lastly, to investigate the effect of age on MSOC, a regression analysis was run. The results showed that the re-gression model was significant,F(1, 238)=50.31,p=.000, and explained 17.1% of the variance in the students’ satis-faction with the online courses. Moreover, as age increases

TABLE 3

Comparison of Means (N=240)

Variable M SD t

Academic status 13.18∗∗∗

Graduate 2.54 0.84

Ungraduate 1.40 0.49

Distance from campus 7.42∗∗∗

Less than 1 mile 1.50 0.63

More than 1 mile 2.24 0.90

Note. The dependent variable was student satisfaction with online courses rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dis-satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

∗p<.10.∗∗∗p<.01.

(as with it [age] come other responsibilities, such as work, family matters), MSOC increases as well (β=.42),t(238)=

7.09, p=.000.

Education-Related Factors

Next, we examined the impact of the other block of variables, referred to as education related, on MSOC using several re-gression analyses. The first variable incorporated was “I like online courses.” The findings revealed that the regression model was significant,F(1, 238)=14.76,p=.000. Further-more, if a student generally liked online courses, then he or she was more satisfied with their online delivery (β=.24),

t(238)=3.84,p=.000; yet, the adjustedR2was very small (.054).

The potential impact to MSOC of whether or not students perceived online courses as an appropriate way of learning in universities was also explored. The regression model was found to be significant,F(1, 238)=9.20,p=.003. Addi-tionally, if a student perceived online courses as a suitable way of learning, then he or she tended to be more satisfied with course online delivery compared with those students who did not accept the general concept of distance learning (β =.19), t(238) =3.03,p =.003. However, adjustedR2

was very small, explaining only 3.3% of the variance in the dependent variable, MSOC.

The degree to which students were familiar with the course background was another potential predictor of students’ sat-isfaction with online courses. The results revealed that, in this case as well, the regression model was significant,F(1, 238)=5.17,p=.024. Furthermore, as expected, a student somewhat familiar with the course background was likely to be more satisfied with the delivery of online courses (β =

.15),t(238)=2.28,p=.024. Nevertheless, adjustedR2was

TABLE 4

Simple Regression Analyses

Variable β ta Fb

1. Age .42 7.09∗∗∗ 50.31

2. I like online courses .24 3.84∗∗∗ 14.76

3. I think online courses are an appropriate way of learning in universities

.19 3.03∗∗∗ 9.20

4. I would take a course online if I was, to some extent, familiar with the course material

.15 2.28∗∗ 5.17

5. How many business courses have you taken online at Gonzaga University?

–.16 –2.48∗∗ 6.15

Note. The dependent variable was student satisfaction with online courses rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dis-satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

∗∗p<.05.∗∗∗p<.01.

adf=238. bdf=1, 238.

very small, only .017; hence, explaining less than 2% of the variance in the MSOC.

The number of courses completed online by students was another variable that was predicted to potentially affect their satisfaction with online courses. The regression model was significant,F(1, 238)=6.15,p=.014. However, the more courses a student acquired online, the less dissatisfied he or she became (β=–.16),t(238)=–2.48,p=.014. AdjustedR2

was still very small, explaining only 2.1% of the variance in the dependent variable, MSOC. Table 4 presents a summary of the regression analyses findings.

Lastly, given that, in addition to online courses, the School of Business Administration at GU offers blended courses (though in much smaller numbers), we performed a paired-sample ttest to investigate whether there was a significant difference in the students’ satisfaction with online courses versus blended courses. The results revealed that there was a significant difference, t(239) = –18.59, p = .000. Fur-thermore, the score of the mean satisfaction with online courses was lower than the score of the mean satisfaction with blended courses (d=–1.15).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study explored the potential sociodemographic and education-related factors that influence students’ satisfaction with online courses. As demonstrated by the analysis, the student who would be more satisfied with the online delivery of courses would fit the following profile: graduate, married, residing off campus, and male. In terms of the education-related predictors, the student for whom the idea of distance learning is appealing, who perceives online instruction to be an appropriate way of learning in universities, and who has

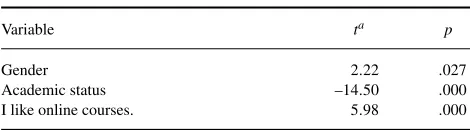

TABLE 5

Multiple Regression Analysis

Variable ta p

Gender 2.22 .027

Academic status –14.50 .000

I like online courses. 5.98 .000

Note. The dependent variable was student satisfaction with online courses rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very dis-satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). Gender was a dummy variable coded as 0 (female) and 1 (male). Academic status was a dummy variable coded as 0 (graduate) and 1 (undergraduate). AdjustedR2=50.72%.F(3, 236)= 80.96,p=.000.

adf=236.

some background regarding the course he or she decides to take online is the type of student who would likely be more satisfied with the online delivery of courses.

Acknowledging that some of the predictors may be mod-erately correlated among themselves, we developed a cor-relation matrix and found some multicollinearity issues. As expected, there were moderate correlations (|r| ranged from 0.52–0.70) among the following independent variables: aca-demic status, marital status, and distance from campus.

We ran multiple regression analyses (dropping the in-significant variables step by step) and found that the statis-tically significant variables affecting a student’s satisfaction with online delivery included academic status, gender, and the student’s inclination to take online courses. The regres-sion model was significant,F(3, 236)=80.96,p=.000, and explained 50.72% of the variance. The results of the final multiple regression analysis are depicted in Table 5.

The Appendix presents the regression equation(s) that can be used to predict a student’s satisfaction with online courses. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that the variable that stood out as having the largest impact on our dependent variable, MSOC, was academic status. The analysis revealed that the simple linear regression model was significant,F(1, 238) = 173.78, p = .000, and explained 42.20% of the variance.

This study provides some insights into factors that impact students’ satisfaction with online courses. The research re-sults demonstrate that online courses might be better received when offered at the graduate level (involving adult popula-tions) than undergraduate level. Furthermore, degrees and certain courses that attract more male (than female) students would be potential candidates for online delivery. As course familiarity seems to play a significant role in a student’s sat-isfaction, it is advisable that core and prerequisite courses not be offered online; on the other hand, elective courses may be offered online. Lastly, we recommend that schools and uni-versities lean toward a blended course-delivery mode (with some face-to-face component) versus 100% online delivery. Regardless of the intended contribution to the academic field, we acknowledge that the study carried some limitations

100 M. S. BEQIRI ET AL.

as well. First, even though we attempted to incorporate a reasonable number of predictors, there are undoubtedly other factors that may impact students’ satisfaction with online courses. Second, the study encompassed students within one single school (School of Business Administration) of one uni-versity. Lastly, we recognize the limitations regarding the small predictive power of certain variables and the issues arising from running several tests, as well as using single-item measures. Further research should be directed toward incorporating other predictors, refining some of the measures, and increasing the sample size by involving other schools and universities.

REFERENCES

Alsop, R. (2004, September 22). WSJ guide to business schools: Recruiters’ top picks (A Special Report); Nose to the grindstone: The secret to Pur-due’s success: Work hard, work right, work together.Wall Street Journal, R5.

Alstete, J. W., & Beutell, N. J. (2004). Performance indicators in online distance learning courses: A study of management education.Quality Assurance in Education,12(1), 6–14.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2005). Is there an optimal design for on-line MBA courses? Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 135–149.

Armstrong, S. (2005). Postgraduate management education in the UK: Lessons from or lessons for the U.S. model?Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 229–234.

Bocchi, J., Eastman, J. K., & Swift, C. O. (2004). Retaining the online learner: Profile of students in an online MBA program and implications for teaching them.Journal of Education for Business,79, 245–253. Boose, M. A. (2001). Web-based instruction: Successful preparation for

course transformation. Journal of Applied Business Research, 17(4), 69–79.

Brown, S. W., & Kulikowich, J. M. (2004). Teaching statistics from distance: What have we learned? International Journal of Instructional Media, 31(1), 19–36.

Campbell, M. C., Floyd, J., & Sheridan, J. B. (2002). Assessment of student performance and attitudes for courses taught online versus onsite.Journal of Applied Business Research,18(2), 45–51.

Desanctis, G., & Sheppard, B. (1999). Bridging distance, time, and culture in executive MBA education. Journal of Education for Business,74, 157–160.

Eberhardt, B. J., Moser, S., & McGee, P. (1997). Business concerns re-garding MBA education: Effects on recruiting.Journal of Education for Business,72, 293–296.

Ebersole, J. (2004). The future of graduate education. University Busi-ness, 7(8), 15–16. Retrieved December 31, 2006, from http://www. universitybusiness.com/viewarticle.aspx?articleid=527

Friga, P. N., Bettis, R. A., & Sullivan, R. S. (2003). Changes in gradu-ate management education and new business school strgradu-ategies for the 21st century. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2, 233–249.

Giacalone, J. A. (1998). Part-time MBA programs: Quality indicators, advantages, and strategies. Journal of Education for Business, 43, 241–245.

Gosling, J., & Mintzberg, H. (2004). The education of practicing managers. MIT Sloan Management Review,45(4), 19–22.

Grandzol, J. R. (2004). Teaching MBA statistics online: A pedagogically sound approach.Journal of Education for Business,79, 237–244. Hollenbeck, C. R., Zinkhan, G. M., & French, W. (Summer, 2006). Distance

learning trends and benchmarks: Lessons from an online MBA program. Marketing Education Review,15(2), 39–52.

Huang, C., & Chuan, M. (2005). Exploring employed-learners’ choice pro-files for VMBA programs.The Journal of American Academy of Business, 7, 203–211.

Larson, P. D. (2002). Interactivity in an electronically delivered marketing course.Journal of Education for Business,77, 265–269.

Lawrence, J. (2003). A distance learning approach to teaching manage-ment science and statistics.International Transactions in Operational Research,10, 127–139.

Lazer, W., & Frayer, D. J. (2000). A 21st century perspective on executive marketing education.Marketing Education Review,10(2), 1–14. McEwen, B. C. (2001). Web-assisted and online learning.Business

Com-munication Quarterly,64, 98–103.

McFarland, D., & Hamilton, D. (winter 2005/2006). Factors affecting stu-dent performance and satisfaction: Online versus traditional course deliv-ery.Journal of Computer Information Systems,46(2), 25–32.

McLaren, C. H. (2004). A comparison of student persistence and perfor-mance in online and classroom business statistics experiences.Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education,2(1), 1–10.

Medlin, B. D., Vannoy, S. A., & Dave, D. S. (2004). An internet-based approach to the teaching of information technology: A study of student attitudes in the United States.International Journal of Management,21, 427–434.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2007).Digest of education statis-tics: Table 290. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved August 6, 2008, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d07/tables/dt07 290.asp

Piotrowski, C. P., & Cox, H. L. (2004). Educational and career aspirations: Views of business school students.Education,124, 713–716.

Rapert, M. I., Smith, S., Velliquette, A., & Garretson, J. A. (2004). The meaning of quality: Expectations of students in pursuit of an MBA. Jour-nal of Education for Business,80, 17–24.

Richards-Wilson, S. (2002). Changing the way MBA programs do business—lead or languish. Journal of Education for Business, 77, 296–300.

Sturges, J., Simpson, R., & Altman, Y. (2003). Capitalizing on learning: An exploration of the MBA as a vehicle for developing career competencies. International Journal of Training and Development,7(1),53–66. Tabatabaei, M., Schrottner, B., & Reichgelt, H. (2006). Target populations

for online education.International Journal on ELearning,5,401–414 Zhao, J. J., Truell, A. D., Alexander, M. W., & Hill, I. B. (2006). Less success

than meets the eye? The impact of Master of Business Administration education on graduates’ careers.Journal of Education for Business,81, 261–268.

APPENDIX

Prediction of Student Satisfaction With Online Courses

y=the dependent variable, student satisfaction with online courses

x1= gender, 1 if student is male and 0 otherwise

x2= academic status, 1 if student is undergraduate and 0 otherwise x3= I like online courses.

The following regression equations can be developed:

1. If a student is male and a graduate ˆ

Y=2.02+.23x3

2. If a student is male and an undergraduate ˆ

Y=.85+.23x3

3. If a student is female and a graduate ˆ

Y=1.86+.23x3

4. If a student is female and an undergraduate ˆ

Y=.69+.23x3