Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Linkage Formation by Small Firms: The Case of A

Rural Cluster in Indonesia

Yuri Sato

To cite this article: Yuri Sato (2000) Linkage Formation by Small Firms: The Case of A

Rural Cluster in Indonesia, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 36:1, 137-166, DOI:

10.1080/00074910012331337813

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331337813

Published online: 21 Aug 2006.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 118

View related articles

LINKAGE FORMATION BY SMALL FIRMS:

THE CASE OF A RURAL CLUSTER IN

INDONESIA

Yuri Sato*

Institute of Developing Economies, Tokyo

This paper analyses forward linkages formed by small firms in Ceper, a rural metal-casting cluster in Central Java, and examines the effects of these linkages in promoting the firms’ development. Firms in the cluster have developed subcontracting linkages with assemblers in the urban modern sector, and putting-out linkages with wholesalers located in the cities. The linkages provide benefits beyond product sales: some firms are stimulated to improve technological capabilities through subcontracting linkages with assemblers; others are supported by trade credits embedded in linkages with wholesalers. In comparing these effects with external assistance, the firms rate technological help from private institutions with a business orientation more highly than that from assemblers, and support from wholesalers more highly than any other source of financial assistance. Government assistance receives a relatively low rating. There is little evidence of effects of clustering, partly because firms consider linkages with the outer economy more strategic.

INTRODUCTION

flexible division of labour among small firms. The second type of research interest is theoretical. Linkages are seen as an intermediate form between market and organisation. In an imperfect market, transaction costs are high, so firms move to form linkages with other firms in order to reduce costs. A linkage here means a continuous transaction relationship between firms by ex ante contract. If the two firms are integrated into one, transaction costs no longer occur; instead, organising costs arise. Organising costs increase as the organisation gets larger, until it chooses linkages to reduce these costs.1 Thus, the theoretical interest is in the

conditions under which linkages are chosen and function as a cost-minimising device.

These two streams of interest were combined in a study by Lall (1980), which stressed the effectiveness of linkage creation in imperfect markets in developing countries. Stimulated by this study, Thee Kian Wie and his colleagues pioneered Indonesia’s empirical study of subcontracting linkages (Thee 1985; Hamid 1985; Sudjono 1985; Erfanie 1985). At that time they concluded that subcontracting linkages in Indonesia had arisen through policy enforcement and did not work effectively, mainly because of the technological weakness of subcontractors. After a decade, however, as some recent studies reveal, subcontracting linkages in Indonesia began to develop, driven by market expansion (Harianto 1993; Thee 1997; Sato 1998).

While the above linkage studies have generally examined backward subcontracting linkages from the perspective of the assembler, recent studies look at forward and horizontal linkages from the viewpoint of small-scale rural firms in developing countries. Studies of rural industrialisation examine rural firms’ forward linkages to the market, either through subcontracting systems, putting-out systems or direct sales (Mizuno 1996; Ono 1998; Hayami et al. 1998). Other studies analyse the dynamism of horizontal linkages or the division of labour among small firms (Kawakami 1998). Another stream of studies focuses on clusters. A cluster is defined here as a spatial concentration of small firms in the same industry (Schmitz 1995; Becattini 1990), which has the potential to evolve into an ‘industrial district’ (Marshall 1920) on the Italian model, characterised by collective efficiency, flexible specialisation, joint action by firms, self-help institutions and common value systems (Becattini 1990). There is increasing agreement that clustering helps small firms to overcome growth constraints and to compete in distant markets (Shmitz and Nadvi 1999).2 In the Indonesian context, while rural cottage industry

In light of the linkage studies reviewed above, this paper examines the forward linkages small firms have formed, by focusing on a rural cluster in Indonesia, and then analyses the effects of linkages in promoting the development of small rural firms. The paper first provides an overview of the rural cluster as a setting for the analysis. It then examines the structure, the nature and the functions of transaction linkages formed by firms in the cluster. The third section analyses the effectiveness of assistance embedded in the linkages when compared with external assistance, and assesses the extent to which collective efficiency is an effect of clustering.

CEPER, A METAL-CASTING CLUSTER IN CENTRAL JAVA

Ceper is known as ‘a village of foundries’. It is a rural cluster of more than 340 small and medium-scale home foundries, located about halfway between Yogyakarta and Solo in Central Java, at the eastern edge of the subdistrict of Ceper in Klaten district.

(high-frequency induction) furnaces in a few cases.4 Progress in this

period was strongly supported by favourable domestic market conditions. Table 1 provides an overview of the casting industry in Ceper in 1997, when production was at its peak, just before the economic crisis. Ceper produces 35,500 tons of casting products, accounting for about 30% of Indonesia’s total annual casting production. The 340 to 350 foundries can be roughly divided into three layers. The first layer consists of about 10 large foundries with integrated machining and assembling processes, sometimes contracting out certain production processes to lower-layer foundries in the cluster. The second layer is composed of medium-sized foundries with some machine tools, and absorbs 70% of the workforce engaged in the Ceper casting industry. The third layer is small home foundries specialising in casting, which account for 60% of the establishments in the cluster. Thus, a correlation is observed between firm size and the degree of integration of the production process.

Tables 2–4 summarise features of the sample firms under study (see appendix for further details of individual firms).5 While the sample

includes only 5% of establishments, in terms of the workforce and production volume it covers one-sixth of the total.6 The majority of the

TABLE 1 The Casting Industry in Ceper, 1997

Number of establishments (units) 340–50

Large (80–250) 10

Medium (20–79) ± 120

Small (1–19) ± 210

Total workforce (persons) ± 4,100 Total production (tons/year) 35,500 Total sales (Rp million) 77,800 Production facilities (units)

Melting furnaces 364

Tungkik furnaces 350

Cupola furnaces 10

Electric furnaces 4

Machine tools ± 1,600

Grind stone machines ± 600

Lathes ± 350

Drilling machines ± 350

sample are medium-sized firms with a workforce of around 40; the large end (a firm with 150 workers, the second largest in Ceper) and the small end (a firm with around 10 workers) are also represented (table 2). The correlation between size and degree of process integration is clearly observed in table 2. However, there is also a preference for integration at the medium level, in firms of less than 50 workers.

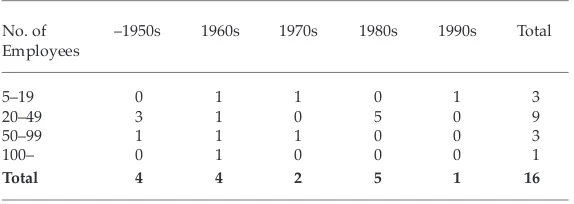

The majority of firms in the sample started business in the 1970s or earlier (table 3). Most of the 10 successor–owners are in this category. Since all firms with more than 50 workers set up their foundry businesses before the 1980s, and all those that started their businesses after the 1980s

TABLE 2 Size Distribution and Degree of Process Integration of Sample Firms in Cepera

No. of Employees C C + M C + M + A Total

1–4 0 0 0 0

5–19 2 1 0 3

20–49 0 5 4 9

50–99 0 1 2 3

100– 0 0 1 1

Total 2 7 7 16

aC: casting; M: machining; A: assembling

Source: Author’s field survey.

TABLE 3 Period of Commencement of Foundry Business by Size of Sample Firm

No. of –1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s Total Employees

5–19 0 1 1 0 1 3

20–49 3 1 0 5 0 9

50–99 1 1 1 0 0 3

100– 0 1 0 0 0 1

Total 4 4 2 5 1 16

have fewer than 50 workers, the natural law that ‘older is larger’ seems to hold true, and this is consistent with the results of rural cluster studies in other countries, including Japan (Itoh and Urata 1995). However, the fact that some samples are ‘old but still small’ indicates that there are some impediments to their expansion.

The data show that almost all owners have a professional background in the metal-casting industry (table 4). What is peculiar in Ceper is the Islamic orientation of their educational background. Of the six owners with higher education, four chose Islam and two chose technology as their educational specialty. Since one of the latter is an ‘immigrant’ from Solo, there is only one Ceper native with a degree in engineering in the sample of 15. Most respondents acknowledged their Islamic orientation; some were educated in pesantren (Islamic junior and senior boarding high schools), and some are engaged in the activities of Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation, suggesting that a common social value system exists in this cluster.

TABLE 4 Background of Present Owners of Sample Firms

Professional Career School Career and Specialty

Succession (child of owner)a 10 Graduate school 2

Related manufacturing 2 Islamic 2 Wage worker 1 University/Academy 4

No answer 2 Islamic 2

Technology 2

Senior high school 5

General 2

Technology 2

Islamic (pesantren) 1 Junior high school 2 Elementary school 2

Totalb 15 15

aIncludes three cases of succession by son-in-law. bOne firm established by the government is not included.

LINKAGES DEVELOPED BY CEPER’S FIRMS

The primary focus of this study is the linkages that Ceper’s firms have developed.7 Most foundries in Ceper manufacture their products on the

basis of orders. Thus our first question is who provides the order: is the order provider an assembler, a distributor, or an end user? Do foundries supply semi-processed goods or final goods? Is the relationship with the order provider continuous or just ‘on the spot’? Is the order repetitive (‘routine’) or temporary (a ‘job order’)? Is the order provider located inside or outside Ceper?

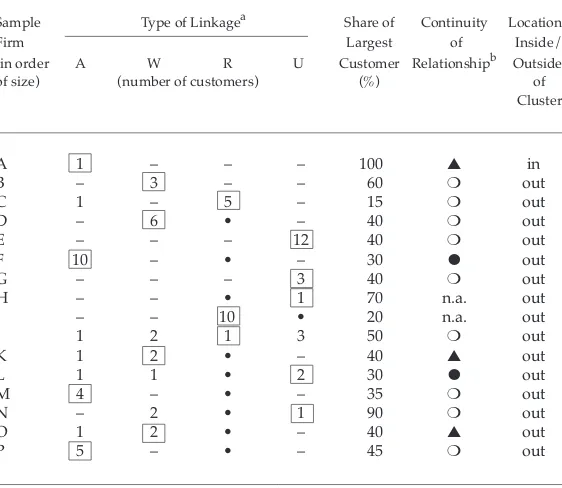

Four Types of Forward Linkage

First, let me present a simple typology of linkages. Linkages are here defined to encompass not only the production process but also the distribution process, until the goods reach the hands of end users (consumers). In the context of this study, there are four types of forward linkages viewed from the perspective of the foundries.

• Type A (Assembler). As a subcontractor, a foundry receives an order from an assembler. The products supplied by the foundry are semi-processed casting components, to be resemi-processed and/or assembled by the assembler.

• Type W (Wholesaler). A foundry receives an order from a wholesaler. Usually, the products are final goods or components for replacement (type W1). But wholesalers are sometimes equipped with machine tools and add some simple machining or assembling processes to the supplied products, particularly if the foundry has no machine tools. In these cases, the products supplied by the foundry are semi-processed goods (type W2). • Type R (Retailer). A foundry receives an order from a retailer. The

products are final goods.

• Type U (User). A foundry receives an order directly from an end user, generally a factory that needs new production equipment or components for replacement. Direct orders from public works projects are also included in this type.

The Plural, Continuous and Interregional Nature of the Transaction Linkages

Table 5 shows the types and characteristics of transactions of the sampled firms. The major findings are as follows.

First, almost all the firms have linkages with plural order providers, and many of them cover plural types of order providers. High dependence on a single order provider is not common. The plurality of linkages is a major reason why we cannot divide firms clearly into two types, i.e.

semi-TABLE 5 Features of Linkages of Sample Firms

Sample Type of Linkagea Share of Continuity Location

Firm Largest of Inside/

(in order A W R U Customer Relationshipb Outside

of size) (number of customers) (%) of

Cluster

A 1 – – – 100 ▲ in

B – 3 – – 60 ❍ out

C 1 – 5 – 15 ❍ out

D – 6 • – 40 ❍ out

E – – – 12 40 ❍ out

F 10 – • – 30 ● out

G – – – 3 40 ❍ out

H – – • 1 70 n.a. out

I – – 10 • 20 n.a. out

J 1 2 1 3 50 ❍ out

K 1 2 • – 40 ▲ out

L 1 1 • 2 30 ● out

M 4 – • – 35 ❍ out

N – 2 • 1 90 ❍ out

O 1 2 • – 40 ▲ out

P 5 – • – 45 ❍ out

aA: with assembler; W: with wholesaler; R: with retailer, U: with end user.

: includes largest customer, •: unspecified plural, –: none.

bContinuity of relationship: ❍: from the start of the business; ●: before the start of

the business; ▲: after the start of the business.

processed goods makers linked to assemblers, and final goods makers selling to wholesalers, retailers or end users. A firm may supply the same kinds of components to assemblers for new assembly and to retailers for replacement; or, more often, a firm may supply components to assemblers and assembled products to end users. Plurality of linkages is the dominant propensity of these firms, partly because of their efforts to diversify risk, and partly because of the ‘small-lot’ and unstable nature of orders. If we examine the linkage types of the largest order providers (customers) of the respective firms (indicated by in table 5), we find that all the four types are prevalent, with neither a prominent preference for a specific type, nor a correlation of linkage type with firm size (as indicated by the order of firms in the left column of the table).

Second, the relationship with the largest order provider tends to be long term, regardless of its type. More than half the firms have maintained the linkages since the start of their business, sometimes in the owner’s predecessor’s time. These continuous relationships can be regarded as a means of lowering transaction costs, including the costs of knowing each other, making a transaction contract (either oral or written), negotiating and bargaining. While in urban areas like Jakarta and Surabaya ‘linkages by spin-out’—where a former employee sets up a small firm to supply to his former employer—increased rapidly after the 1980s, such cases are rare in this rural cluster.

Third, the largest order provider of the firm is located outside Ceper except in one case. There is a clear preference for transactions with customers outside Ceper. As a result, intra-cluster inter-firm linkages— vertical subcontracting and horizontal division of labour—seem to be less developed in Ceper than in other reported clusters (Smyth 1992), despite the divisibility of the production process in the machinery industry.8

Type A: Subcontracting Linkages with Assemblers

local brands, located outside Ceper. The third pattern is that upper-layer foundries (e.g. firms M and P) get subcontracts from large-scale assemblers of machinery making popular brands, including foreign joint ventures located in metropolitan Jabotabek (greater Jakarta) and other large cities such as Surabaya. The last pattern demonstrates that subcontracting linkages with modern manufacturing have already reached the top layer of this cluster. We will look at the third pattern in more detail.

Firm M and Firm P: Typical Type A Linkages. These two firms are among the leading firms in Ceper, and are known as subcontractors to first-rank brand machinery manufacturers. Their major products are such casting components as pulleys for Yammer (Japan) handtractors, pumps for Bukaka (Indonesia) and Rafkin (USA) oil boring facilities, and components for UT (Indonesia) and Komatsu (Japan) forklifts. The assemblers are located in Surabaya, Jakarta and Batam. Since the start of their business, firm M has had transactions with Yammer and firm P with Bukaka. Why do these firms give priority to subcontracting rather than to other types of transactions?

The first reason is low business risk. The manager of firm M points out that the continuity of transactions in terms of buyers and products reduces total business risk in the long run, despite the low margin per order. According to him, the average profit margin in subcontracting orders is 10–17.5%, while it is 30–60% in the case of job orders because of the risk premium. Even such high margins as the latter, however, are often offset by costs in making moulds for only temporary use, and by losses from unexpected discontinuation of the transaction. In terms of risk management, the ideal pattern with the lowest risk, he says, is routine subcontracting linkages with three to five assemblers.

(of a firm P employee), and a dispatch of engineers by the assemblers (to firm M).

In the backgrounds of their founder–owners, the two firms have a common feature. Neither owner is a native of Ceper: both are traders from other towns in Central Java, each of whom has married the daughter of a Ceper foundry owner and settled in Ceper. There may be some link between their outsider status and their outstanding enterprising spirit in relation to technological progress.

Type W: Putting-Out Linkages with Wholesalers

The firms that have plural types of linkages provide us with a comparative view.

Firm O: Type A vs Type W.The case of firm O is helpful in allowing us to compare type A and type W linkages, because this firm has a subcontracting tie with a major local assembler of agricultural machinery in Surabaya, and concurrently has a continuous relationship with several wholesalers in Surabaya and Jakarta.

The founder–owner of firm O is regarded as a reliable subcontractor by the assembler, but he says: ‘For us, subcontracting is clearly important as a routine matter. However, if we once become dependent on it, we become blind.’ His point is that an entrepreneur should be close to the market. That is why he attaches greater importance to linkages with wholesalers. It is the wholesalers that provide him with live market information and orders reflecting current market trends. They are also familiar with firm O’s production capabilities. Further, the wholesalers pay the owner two weeks after delivery, whereas it takes one to two months for the assembler to pay him. The owner’s relationship with two wholesalers has lasted since his independence from his father-in-law’s foundry in 1982, while the relationship with the assembler dates from 1987.

In essence, given the low costs of production in this rural cluster, the owner of firm O considers it more strategic for Ceper’s foundries to manufacture products of lower quality but competitive price, making use of linkages with wholesalers, rather than to try to make higher-quality products under well known brand names through subcontracting linkages with large assemblers.

type W with two wholesalers for items such as manhole covers (35% of sales), of type R with one retailer for diesel engine pulleys and water pumps (50% of sales), and of type U with one pharmaceutical factory for machinery spare parts (5% of sales as of 1998).

Of the four types of linkages, the founder–owner of firm J considers type W the most advantageous. Why? First, wholesalers function as matchmakers between demand trends in the market and the capabilities of each supplier. The owner of firm J says: ‘The wholesalers are very selective. But once they judge that the order fits me, it means I’ve got an assured market with little risk of returns or rejects.’ With their capacity for collecting and analysing market information, wholesalers not only know the market well but also bear the risk of uncertainty in marketing on behalf of firm J.

The second advantage of type W for firm J is that it lowers the firm’s financial burden. Besides lowering financial costs because of shorter-term sales payments, the wholesalers often provide working capital by means of advance payments. Firm J provides a comparison of the payment terms of the four types of linkage. In the case of the assemblers and the factory, it is more than one month after delivery before the firm receives sales payments, owing to the buyers’ bureaucratic procedures. In the case of the retailer, payment also occurs one month on average after the products are sold; if unsold, the products are returned to him after a month with no payment. On the other hand, the wholesalers pay 40% of the order value in advance so that firm J can procure raw materials with it. The rest is paid to the firm just one week after delivery. This case illustrates the advantages, in terms of financial costs and risks, of the trade credit provided by wholesalers to supplier firms.

Firm J has paid little attention to improving product quality, unlike firms M and P. This is not due to the owner’s lack of technological awareness (he is one of the two engineering graduates in the sample), but to cost calculations. According to him, it is costly to improve quality by upgrading facilities and controlling material composition. He would not do this unless order providers bore these costs. In the linkage with wholesalers, he has never faced serious complaints about quality, because the wholesalers lack the knowledge to pay precise attention to technological matters.

Firm B and Firm D: Typical Type W. Firm B and firm D are examples of firms that concentrate on transactions with wholesalers. Both are cases of type W2, where the wholesalers undertake some manufacturing processes.

order value (Rp 20–25 million in total) for the firm to procure raw materials. Firm D’s products become the collateral for the funds advanced by the wholesaler, who deducts the advanced amount in instalments from subsequent sales payments to firm D. When the wholesaler happens to obtain steel scraps, he buys them and sends them as raw materials in kind to firm D. It is owing to this system that the owner of firm D has never felt the need for other external finance. When the owner moved into machining from being a specialised home foundry in 1992, the wholesaler helped him with initial guidance on how to select and use machine tools and how to make jigs.

Firm B has linkages with three wholesalers-cum-repairshops-cum-assemblers located in Solo. One of them has a wide marketing network spreading outside Java. The owner of firm B became acquainted with these wholesalers when he worked at a foundry firm as a salesman. Like his father, he had been engaged in the foundry business as a wage worker since his elementary school days (he did not graduate). Despite his long working career, he had only a tiny landholding and no other savings or inheritance when he wanted to become independent. It was one of the wholesalers who lent him funds equivalent to twice the value of his order (Rp 10 million in total), with which he could afford to buy a tungkik furnace and raw materials. This case shows, first, that a career as a wage worker does not produce a surplus for initial investment and, secondly, that advances provided by wholesalers can cover set-up costs and investment capital in some cases.

The Wholesaler as ‘Putter-Out’. We have briefly surveyed examples of linkages with wholesalers. Usually called grosir, wholesalers collect and allocate orders to foundries. Although they are sometimes equipped with manufacturing facilities, by nature they are not manufacturers but intermediaries and coordinators of orders. Most of the wholesalers in the study are medium or small scale, and are located not only in big cities but also in smaller cities like Yogyakarta and Solo.

finance the firms’ working capital and sometimes even their investment capital, including set-up costs. In this respect, such linkages with wholesalers can be considered a variation of the putting-out system.

The Coexistence of Two Systems—Dual Structure or Evolutionary Process?

Type A is a subcontracting system and type W is a variation of the putting-out system. The study has revealed that both subcontracting linkages and putting-out linkages permeate this rural cluster. Subcontracting linkages with modern industry, with foreign joint venture assemblers of leading brands of machinery at the apex, have already reached the top layer of the cluster. Meanwhile, the foundries in every layer have formed linkages with wholesalers outside the cluster who play the role of putters-out. In Japan’s historical experience, sophisticated subcontracting systems in the modern machinery industry developed in the postwar period, whereas the putting-out system prospered in the initial stages of development of the industry in the 1930s. Here in Ceper, the two systems coexist contemporaneously.

Should this coexistence be regarded as reflecting a dual structure or an evolutionary process? Table 6 may offer insight into this question. In the table, the sample firms are rearranged in order of firm age, measured by the period from the start of the foundry business. It becomes obvious that the firms whose largest customers are assemblers are relatively old firms and those whose largest customers are wholesalers are younger firms. This suggests that linkages with wholesalers have significance for younger firms at the stage of initial accumulation. Are these firms evolving towards linkages to assemblers? What is interesting is that none of the firms sees evolution from type W to type A linkages as desirable (see the middle column of table 6). Instead, some firms, even the old ones, show an inclination towards independence from subcontracting linkages and towards enhancing internal integration. Thus the evolutionary path the sample firms are most inclined to follow seems to begin with intra-cluster subcontracting (Ain) or sales to retailers (R), then to make use of linkages with wholesalers (W2) and later to integrate processes in order to supply assembled final products under the linkages with wholesalers (W1) or end users (U) [Ain/R➔W2➔W1/U]. The path in which linkages are

TABLE 6 Types of Linkages, Firm’s Inclination to Evolve, and Firm Age

Sample Type of Linkagea Inclination Year of

Firm to Evolveb

(in order A W R U Starting Establish- Starting

of firm (number of customers) Foundry mentc

Relation-age) Business ship

L 1 1 • 2 U➔n.a. 1940s 1982 ● F 10 – • – A➔R 1950s 1978 ●

G – – – 3 U➔ 1950s 1958 ❍

N – 2 • 1 U➔ 1950s 1994 ❍

C 1 – 5 – R➔ 1960s 1981 ❍

I – – 10 • R➔ 1960s 1980 n.a.

M 4 – • – A➔ 1960s 1986 ❍

P 5 – • – A➔ 1960s 1980 ❍

A 1 – – – Ain➔ 1970s 1988 ▲ O 1 2 • – W2➔W1 1970s 1979 ▲

D – 6 • – W➔ 1980s 1986 ❍

E – – – 12 U➔ 1980s 1985 ❍

H – – • 1 Ain➔U 1980s 1987 n.a. J 1 2 1 3 R➔W 1980s 1986 ❍

K 1 2 • – W➔ 1980s 1991 ▲

B – 3 – – W➔ 1990s 1990 ❍

aSee table 5, note a; ‘Ain’ indicates a linkage with an assembler within the cluster. bAn arrow shows a change of linkage type in the past or an inclination to change

in the future. An arrow with nothing to the right of it indicates no change and no specific inclination.

c‘Year of Establishment’ means the year in which a business entity was formed,

either as an unlimited or a limited company.

THE EFFECTS OF LINKAGES IN PROMOTING THE

DEVELOPMENT OF SMALL FIRMS

Assistance Embedded in the Linkages

The second step of this study is to analyse the effects linkages have on the promotion of small firms’ development. We will assess the relative effectiveness of assistance embedded in the inter-firm transaction linkages compared with that of external assistance, including government programs. The question asked of each firm is: whose assistance has been most effective for its business?

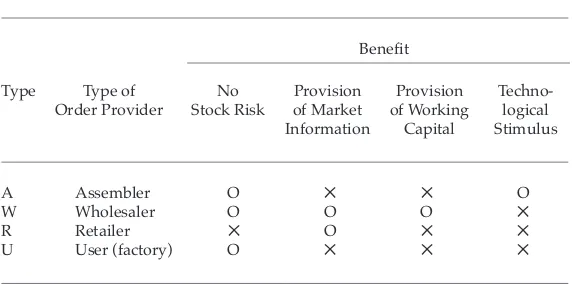

Table 7 presents simplified results of the analysis in the previous section in light of the benefits firms receive from linkages with each type of order provider. As the table shows, order providers other than retailers bear stock risk by accepting ordered products regardless of ex post market circumstances; wholesalers and retailers who are sensitive to market trends offer live market information to the producers; wholesalers often provide working capital by paying in advance; and assemblers tend to stimulate technological progress in subcontractors. In terms of the effects in question, types A and W offer more benefits than types R and U.

Details of assistance offered in type A and type W linkages are compared in table 8.9 In provision of technological assistance, assemblers

have the advantage over wholesalers. The assistance they give ranges from general technical guidance, instruction in the use of machinery and

TABLE 7 Benefits of Linkages for Foundries

Benefit

Type Type of No Provision Provision Techno-Order Provider Stock Risk of Market of Working logical

Information Capital Stimulus

A Assembler O ✕ ✕ O

W Wholesaler O O O ✕

R Retailer ✕ O ✕ ✕

U User (factory) O ✕ ✕ ✕

jigs, and training of workers, to the dispatch of engineers to the firm. There is, however, a wide variation among assemblers in the degree of assistance provided. At one extreme is the case of the top-layer firm P, which has received almost every kind of assistance from its large assemblers in Jakarta; at the other is firm F, which has never received any technological assistance from its assemblers, located mainly in small cities like Solo and Malang. Even at the level of top-layer firms, the assistance is not provided regularly, but only when a problem or a specific need arises. Regular inspection tours and vendor control systems, which some major foreign-brand automobile and electronic assemblers in Jakarta are instituting, have not yet infiltrated into this rural cluster.

TABLE 8 Assistance Embedded in Inter-Firm Transactions

Assembler (5)a Wholesaler (5)a

Technological Assistance

Guidance 3 0

Instruction in machinery use/jig use 2 1 Providing machinery/tools 1 0

Quality control 1 0

Worker training/engineer dispatch 2 0

Financial Assistance

Capital participation 0 0

Investment loans 0 1

Advance payment 0 4

Machinery leasing 1 0

Other assistance

Providing raw materials 1 1 Information/guidance on market 0 2

aFigures in parentheses indicate the number of sample firms covered in the table.

The numbers do not coincide with those in table 5, because table 8 includes cases where an assembler or wholesaler is not the firm’s largest order provider.

As for financial assistance, capital participation is not usual in either linkage type. The advance payment system adopted by wholesalers is a significant exception, and no assembler in the sample adopts this system regularly. As described earlier, some wholesalers pay in advance, say, 40% of the order value, to allow supplier firms to overcome a bottleneck in working capital. Flexible application of this system enables some firms even to invest in production facilities. Repayment can be made in instalments or in the form of products. This system is crucial, especially for lower-layer firms like firm D and for new entrants like firm B, which have little access to other external sources of finance. A comparison with other external financing is made below.

Access to market information is another benefit of linkages with wholesalers. Some firms place a high value on the wholesalers’ capacity to analyse product demand trends despite often having limited technological knowledge of how to make the products. Assemblers, on the other hand, are not rated highly as transmitters of market information. This is related to the fact that, in contrast with Japan’s subcontracting system, it is rare that assemblers and subcontractors jointly engage in product development based on market analysis.

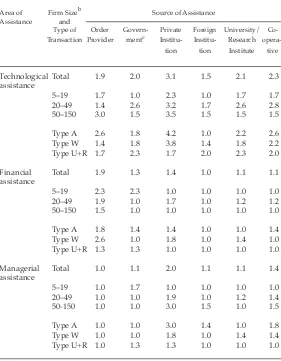

Comparison with External Assistance

The sample firms were asked to evaluate the effectiveness of assistance they have so far received, by source and area of assistance, on a scale of 1 to 5. The sources of assistance are: (1) order providers; (2) the government, e.g. the Ministry of Industry and Commerce, and state-owned corporations; (3) private institutions, e.g. private companies (other than order providers), industrial associations, and the Astra Dharma Bhakti foundation, which has a branch office in Ceper to render business assistance; (4) foreign institutions, e.g. United Nations and German and Japanese government organisations, which carry out directly or through the Ministry of Industry and Commerce such programs as dispatch of foreign experts, seminars and training abroad; (5) universities and research institutes; and (6) cooperatives, the industrial cooperative in Ceper in particular.

The results are summarised in table 9. On the whole, they tell us that a relatively high value (2.0 or above) was put on technological assistance, especially from private institutions (private institutions > cooperatives > universities > government > order providers), but that the evaluation of financial and managerial assistance from all sources was by and large low (2.0 or below).

TABLE 9 Evaluation on Effectiveness of Assistance by Sourcea

Area of Firm Sizeb Source of Assistance

Assistance and

Type of Order Govern- Private Foreign University/

Co-Transaction Provider mentc Institu- Institu- Research

opera-tion tion Institute tive

Technological Total 1.9 2.0 3.1 1.5 2.1 2.3 assistance

5–19 1.7 1.0 2.3 1.0 1.7 1.7 20–49 1.4 2.6 3.2 1.7 2.6 2.8 50–150 3.0 1.5 3.5 1.5 1.5 1.5

Type A 2.6 1.8 4.2 1.0 2.2 2.6 Type W 1.4 1.8 3.8 1.4 1.8 2.2 Type U+R 1.7 2.3 1.7 2.0 2.3 2.0

Financial Total 1.9 1.3 1.4 1.0 1.1 1.1 assistance

5–19 2.3 2.3 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20–49 1.9 1.0 1.7 1.0 1.2 1.2 50–150 1.5 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Type A 1.8 1.4 1.4 1.0 1.0 1.4 Type W 2.6 1.0 1.8 1.0 1.4 1.0 Type U+R 1.3 1.3 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0

Managerial Total 1.0 1.1 2.0 1.1 1.1 1.4 assistance

5–19 1.0 1.7 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 20–49 1.0 1.0 1.9 1.0 1.2 1.4 50-150 1.0 1.0 3.0 1.5 1.0 1.5

Type A 1.0 1.0 3.0 1.4 1.0 1.8 Type W 1.0 1.0 1.8 1.0 1.4 1.4 Type U+R 1.0 1.3 1.3 1.0 1.0 1.0

aEffectiveness of assistance is measured on a scale of 1 to 5 ; 1 = not effective; 3 =

moderately effective; 5 = highly effective. Effectiveness was evaluated by each firm and the responses converted to a value by the author.

bThe size of the firm is measured by the number of employees. cIncludes state-owned corporations.

technological assistance provided by private institutions are middle and upper-layer firms and those with type A and type W linkages. Upper-layer firms and those with type A linkages also give relatively high points to technological assistance by order providers. This same segment also evaluates managerial assistance by private institutions as moderately effective. These results indicate that the upper-layer firms, especially those who have subcontracting linkages with assemblers, actively absorb technological and managerial knowledge offered by private institutions, the Astra Foundation in particular. Although daily transactions with assemblers stimulate these firms to improve their technological capabilities, the firms themselves regard the assistance of the Astra Foundation as more effective than that of assemblers. This Foundation has frequently given practical guidance on moulding, casting, drawing and ferro specifications at its branch office in the centre of Ceper,10 and

has also accepted apprentices into the machinery companies under the Astra group, with the intention of nurturing the firms to become qualified subcontractors to the group in the future. The results show that business-oriented schemes of this kind by private institutions have infiltrated this rural area, bringing positive reactions from some firms.

In the financial sphere, however, assistance by the Foundation is less important. Relatively high points for financial assistance are given to order providers by the lower-layer firms and firms with type W linkages. This indicates that trade credits rendered by wholesalers are still much more important than other forms of external financial assistance, particularly for small and cottage-scale firms.

Low Evaluation of Government and Foreign Assistance

Government and foreign assistance received a low evaluation compared with private institutions, order providers and cooperatives (table 9). In respect of foreign assistance, this may be evidence that it is difficult for assistance schemes of foreign institutions to reach these layers of firms in rural clusters.

criticism was directed at the bureaucratic character of assistance delivery. A manager pointed out that there was a rush of guidance at the end of year, as if the government’s aim was to achieve a certain target of program execution. He claimed that neither firms’ needs nor their time schedules were considered and coordinated by the relevent ministries. The ‘foster father (bapak-angkat) system’, promoted by the government in the mid 1980s to foster linkages between large and small firms, was considered by some firms as no more than government propaganda, because there was no substantial effect in terms of linkage development in this cluster. As these criticisms suggest, this rural cluster had been identified as one of the target groups of the government’s small and medium enterprise (SME) development policy, but the programs were less than responsive to the recipients’ needs.

Given these observed weaknesses of government assistance, one firm owner asserted that ‘there is no way for the government to assist us directly’. The government, in his view, has only two roles: to provide information needed by firms and to facilitate the establishment, maintenance and expansion of firms’ businesses. It is worth listening attentively to these living voices of rural cluster firm owners.

Financial Costs and Accessibility

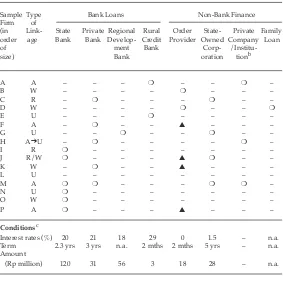

Apart from studying the firms’ own views, we can assess the effectiveness of financial facilities rendered to firms by looking at costs and accessibility. Table 10 shows the financial sources the sample firms have actually accessed. This picture does not coincide with their subjective evaluation of the effectiveness of financial assistance.

The table as a whole demonstrates that the firms have access to a wide variety of external sources of finance, ranging from state and private banks to state-owned corporations, a leasing company and venture capital. Even the smallest sample firm had been able to obtain bank loans. However, only the upper-layer firms have access to the most advantageous state-bank facilities—large loans at relatively low interest rates—while the highest-cost, shortest-term and smallest loans from rural credit banks are obtained by the lower-layer firms. This reflects the fact that the formal bank credit market works with some degree of effectiveness, with financial costs proportional to each borrower’s business risk and related transaction costs.

interest rates were negative, given that inflation was above 5%) and the repayment period was five years, longer than for bank loans. Quite a number of firms in Ceper have used such loan schemes in the framework of the SME promotion policy that obliged state-owned corporations to pool 1–5% of profits for this purpose. Moral hazard is not reported in this study, but how effectively these soft loans have worked in comparison with loans will need further careful investigation.

TABLE 10 Financial Costs and Accessibility by Source of Financinga

Sample Type Bank Loans Non-Bank Finance

Firm of

(in Link- State Private Regional Rural Order State- Private Family

order age Bank Bank Develop- Credit Provider Owned Company Loan

of ment Bank Corp-

/Institu-size) Bank oration tionb

A A – – – ❍ – – ❍ –

B W – – – – ❍ – – –

C R – ❍ – – – ❍ – –

D W – – – – ❍ – – ❍

E U – – – ❍ – – – –

F A – ❍ – – ▲ – – –

G U – – ❍ – – ❍ – –

H A➔U – ❍ – – – – ❍ –

I R ❍ – – – – – – –

J R/W ❍ – – – ▲ ❍ – –

K W – ❍ – – ▲ – – –

L U – – – – – – – –

M A ❍ ❍ – – – ❍ ❍ –

N U ❍ – – – – – – –

O W ❍ – – – – – – –

P A ❍ – – – ▲ – – –

Conditionsc

Interest rates (%) 20 21 18 29 0 1.5 – n.a.

Term 2.3 yrs 3 yrs n.a. 2 mths 2 mths 5 yrs – n.a.

Amount

(Rp million) 120 31 56 3 18 28 – n.a.

a❍: major source; ▲: minor source; –: non-existent.

bA: rural financier; H: machinery leasing company; M: venture capital company. cAverage of sample. Interest rates are those before the sharp rise due to the

We can confirm again the relative importance of financial assistance from order providers, usually in the form of advance payment by wholesalers. The table shows that this is one of the most popular sources of finance, though it complements other major sources in the case of middle and upper-layer firms. Compared with other forms of external financing, its advantages for borrowers lie in the absence of interest payments, collateral, and administration costs, and in the flexible terms of repayment. Further, financing embedded in transaction linkages has some risk-controlling effects that are absent from other forms of financing. Default risk for lenders is low, since the lenders are the buyers of goods, so the traded goods themselves function as collateral in the trade credits. Given that trust is the only basis for the firms being paid in advance, the system would never work again once a firm had cheated the lender– wholesaler. This relationship would work as a brake for moral hazard on the part of the borrower firms. Financing arrangements between two parties linked in a business transaction also help avoid adverse selection, which can often take place under incomplete information.

Limited Effects of Clustering

Finally, we examine the effects of clustering in Ceper. Clustering effects consist of unintended positive effects, or passive externalities, and intended positive effects, or active externalities, of the cluster.11 The former

includes specialisation, division of labour, informal information networks, diffusion and accumulation of knowledge on markets and technology, and accumulation of skilled workers in the cluster. Active externalities include joint actions in pursuit of common interests by the firms themselves, or by government or private institutions. These two kinds of externalities can reduce transaction costs and raise ‘collective efficiency’ for the firms in the cluster (Mishan 1971; Schmitz 1992; Albaladejo 1999; Schmitz and Nadvi 1999).

(5–10 teams in the cluster), and independent craftsmen specialising in making casting moulds (about 5 persons in the cluster).12 Meanwhile,

the fact that some outside traders settled in Ceper through marriage and set up foundries there indicates that the cluster exhibits the effect of low ‘search and reach’ costs for outside traders of casting products and steel scraps and for potential workers. This search and reach effect can be ascribed largely to Ceper’s location, on the trunk road leading from the centre of Java to Surabaya, and between Yogyakarta and Solo, two old centres of dense trade intermediation.

There is little evidence of such activities as joint procurement of inputs, joint marketing of outputs, joint recruitment and sharing of workers, or self-help institutions of owners, managers or workers. An exception is the industrial cooperative, which receives orders mainly from state-owned corporations, allocates them to member firms, collectively procures inputs for the orders and collects outputs for delivery. This service is significant for the lowest-layer home foundries, which have no marketing linkages outside the cluster. The cooperative is now democratically managed under the leadership of local industrialists, and is known as one of the leading industrial cooperatives in Indonesia, though its establishment in 1976 was a purely government initiative. The existence of an active industrial cooperative may have influenced the decision of the government and private institutions to make this cluster a policy target. Another interesting development since the economic crisis is that some quick-witted firm owners have begun to sell to larger firms in the cluster the raw materials left unused because of the fall in their production. Despite these activities, however, joint actions cannot be seen as a major stream of business activity among firms in the cluster as a whole.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this paper has been to study the structure and nature of the linkages that the firms in a rural cluster have formed and to examine the effects of linkages and clustering in promoting the firms’ development, comparing these effects with external assistance.

The main findings are as follows. A subcontracting system and a putting-out system coexist in this rural cluster. Subcontracting linkages with the urban modern machinery industry, with large assemblers at its apex, have reached top-layer firms in the cluster. At the same time, many firms have formed linkages with wholesalers outside the cluster. The wholesalers function as putters-out, intermediating and coordinating orders, transmitting market information and reducing the firms’ financial costs by offering trade credits. The two systems can be seen as coexisting in a dual structure, rather than representing sequential phases in an evolutionary process, since most firms are inclined to be internally integrated, making use of linkages with wholesalers, rather than to evolve into subcontractors of the major machinery assemblers.

In evaluating the assistance they receive through linkages, Ceper firms indicated that assemblers do not provide a great deal of technological assistance, although some firms are stimulated to improve their capabilities through subcontracting linkages with assemblers. The firms place a higher value on assistance rendered by private institutions with a similar business orientation. Apart from this source, however, external assistance, including government assistance, is seen as of generally low value, partly because of its limited applicability to the firms’ actual conditions. While a formal bank credit market has infiltrated this cluster, trade credits embedded in linkages with wholesalers (putters-out) still play a decisive role, especially for lower-layer and younger firms seeking to expand their business. Trade credits within the putting-out system not only lower firms’ financial costs but also help to control default risk and to restrict firms’ moral hazard in repayment.

the development of firms, and of the cluster itself, apart from passive search and reach effects for outsiders. Given that the cluster is located in an area with dense transport and trade intermediation, linkages with firms outside the cluster are not difficult to develop, and have played a central role in the firms’ pursuit of their business interests. The firms in this cluster may thus have little need to enhance intra-cluster collective efficiency. This suggests that linkage formation within the cluster can be significantly affected by linkage formation with the world outside it, and by conditions on the circumference of the cluster.

The findings of this study leave some tasks for further investigation. First, they suggest that the costs of intra-cluster linkage formation are higher than those of forming linkages outside the cluster. Identifying the reasons for these higher costs might allow impediments to intra-cluster linkages to be overcome, enhancing collective efficiency in the cluster. Second, it is worth analysing how the inclination of these small rural firms toward internal integration can be explained economically, given the concept of the linkage as a cost-minimising device. It is reported that some small firms in urban areas have been shifting away from integration and toward division of labour and specialisation as they become exposed to market competition and are forced to meet strict and urgent demands while keeping costs low. This observation might also have implications for the possible evolutionary path of small firms in this rural cluster as they face changes in market competition conditions.

NOTES

* This paper is part of the outcome of research and fieldwork I conducted during a stay in Indonesia from 1996 to 1999 as an overseas senior research fellow of the Institute of Developing Economies in Japan. For help in conducting fieldwork in Ceper, I am very grateful to the respondents, the industrial cooperative and members of UIUKK (Information Unit for Small Enterprises and Cooperatives) Batur Jaya, a private guidance unit under the Astra Dharma Bhakti Foundation, especially Umardani N.H., Soejitno, Anas Yusuf Mahmudi, Krisni Murti M.S., and Yohanes Sancahyohadi. The paper also benefited much from the helpful comments of an anonymous referee.

1 This is the simplest analysis, as presented by Coase (1937). It was developed further by Klein, Crawford and Alchian (1978) and Williamson (1979). See also Lall (1980) for application to developing economies.

3 For studies of small rural firms and clusters based on fieldwork, see Mizuno (1996); Thee (1993); Smyth (1992); and Sandee and Weijland (1989); their major focus was not linkages, however.

4 Based on interviews by the author in Ceper, mainly at the industrial cooperative (Koperasi Industri Batur Jaya), at a regional government owned foundry first established as a pilot project, and at UIUKK Batur Jaya (see note * above). 5 The field study was conducted in September 1998 by means of intensive

interviews with owners and managers of firms, based on a questionnaire prepared and completed by the author.

6 Sampling was not random in the strict sense, so the results are not free from sampling bias. Although information collected was complemented by overviews by some informants, findings from the sample cannot be said to represent general tendencies in Ceper. Given these limitations, the paper simply presents conclusions based on the observed facts of the sample. In addition, because fieldwork was conducted in the midst of the economic crisis, there could be a sampling bias toward surviving firms with surviving linkages, although inactive firms were intentionally included in the sample. However, since the interviews covered the historical development of the firm, their results are not seriously distorted by the crisis. The impact of the crisis on this rural cluster is another important topic, but is beyond the scope of this paper. 7 Linkages, as defined here, are formed as a result of negotiation between two

parties, and take the form of an ex ante contract that reflects the parties’ respective bargaining power. Thus they are not formed unilaterally. 8 There are two exceptions, which are of a non-private nature. One is a regional

government owned factory (a pilot project initially established by the central government) which has 24 subcontractors in Ceper, 20 undertaking machining, three simple casting and one high-grade casting. The other is an industrial cooperative, which receives orders and allocates them among member firms in Ceper. For instance, 75 out of 195 member firms have taken part in a project for the state-owned railway company in which they undertake casting of train brake components, and use machining facilities in the cooperative if they do not have machine tools.

9 Type U and type R are omitted for simplicity. In linkages with user-factories (type U), two state-owned corporations have provided assistance to sample firms in the form of investment loans and technical support respectively. Retailers (type R) have provided little assistance other than market information. 10 This guidance is provided in close cooperation with Ceper’s industrial

cooperative.

11 Schmitz (1992) and Schmitz and Nadvi (1999) refer to the former as unplanned, circumstantial, incidental and passive collective efficiencies, and the latter as planned, consciously pursued, deliberate and active collective efficiencies. The former idea overlaps substantially with Marshallian external economies. 12 By comparison, in Kawaguchi, a traditional metal-casting cluster in Japan,

differentiated over time, but specialised teams or experts—such as firing teams, mould experts, traders in specific raw materials, and breakers of casting remnants—developed in the cluster.

REFERENCES

Albaladejo, M. (1999), ‘Clustering: Strategy for Survival or Alternative for SME Development?’, in Y. Koike and K. Horisaka (eds), New Production System in Latin America: An Alternative to Import Substitution Model, Institute of Developing Economics, Tokyo.

Becattini, G. (1990), ‘The Marshallian Industrial District as a Socio-Economic Notion’, in F. Pyke, G. Becattini and W. Sengenberger (eds), Industrial Districts and Inter-firm Co-operation in Italy, ILO, Geneva.

Coase, R. (1937), ‘The Nature of the Firm’, Economica 4: 386–405.

Erfanie, S. (1985), ‘Pengembangan Industri Perakit dengan Sistem Subkontraktor: Suatu Studi Kasus tentang Perusahaan Subkontraktor di Daerah Tegal [The Development of the Assembly Industry through the Subcontractor System: A Case Study of Subcontractor Firms in Tegal]’, Masyarakat Indonesia 12 (3): 275–88.

Hamid, A. (1985), ‘Pengembangan Industri Komponen Melalui Kaitan Vertikal: Studi Kasus tentang Perusahaan Perakit Mesin Diesel [The Development of the Components Industry through Vertical Linkages: A Case Study of Diesel Engine Firms]’, Masyarakat Indonesia 12 (3): 233–51.

Harianto, F. (1993), ‘Study on Subcontracting in Indonesian Domestic Firms’, Indonesian Quarterly 21 (3): 331–43.

Hayami, Y., M. Kikuchi and E.B. Marciano (1998), ‘Structure of Rural-Based Industrialization: Metal Craft Manufacturing on the Outskirts of Greater Manila, the Philippines’, The Developing Economies 36 (2): 132–54.

Itoh, M., and S. Urata, (1995), ‘Small and Medium Enterprise Support Policies in Japan’, Discussion Paper 95-F-8, University of Tokyo, Tokyo.

Kawakami, M. (1998), ‘Inter-Enterprise Division of Labour, Enterprise Growth and Industrial Development: The Case of Taiwan’s Personal Computer Manufacturing Industry’ (in Japanese), Ajia Keizai 39 (12): 2–28.

Klein, B., R.G. Crawford, and A.A. Alchian (1978), ‘Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive Contracting Process’, Journal of Law and Economics 21: 297–326.

Lall, S. (1980), ‘Vertical Inter-Firm Linkages in LDCs: An Empirical Study’, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 42 (3): 203–26.

Marshall, A. (1920), Principles of Economics, 8th ed., Macmillan, London.

Mihira, Sylvia T. (1998), ‘Small-Scale Metal Casting Industry in Indonesia: Situation and Problems’, Asian Cultural Studies III-A (8): 71–87.

Mishan, E. (1971), ‘The Postwar Literature on Externalities: An Interpretive Essay’, Journal of Economic Literature 9 (1): 1–28.

Ono, A. (1998), ‘Market Formation through Rural Industrialisation: The Case of the Rural Hand-Weaving Industry in Laos’ (in Japanese), Azia Keizai 49 (4): 2–20.

Sandee, H., and H. Weijland (1989), ‘Rural Cottage Industry in Transition: The Roof Tile Industry in Kabupaten Boyolali, Central Java’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 25 (2): 79–98.

Sato, Y. (1998), ‘The Machinery Component Industry in Indonesia: Emerging Subcontracting Networks’, in Y. Sato (ed.), Changing Industrial Structure and Business Strategies in Indonesia, Institute of Developing Economics, Tokyo. Schmitz, H. (1992), ‘On the Clustering of Small Firms’, IDS Bulletin 23 (3): 64–9. —— (1995), ‘Collective Efficiency: Growth Path for Small-scale Industry’, Journal

of Development Studies 31 (4): 529–66.

Schmitz, H., and K. Nadvi (1999), ‘Clustering and Industrialisation: Introduction’, World Development 27 (9): 1,503–14.

Smyth, I. (1992), ‘Collective Efficiency and Selective Benefits: The Growth of the Rattan Industry of Tegalwangi (Indonesia)’, IDS Bulletin 23 (2): 51–6. Sudjono, R.A. (1985), ‘Pengembangan Sistem Subkontraktor di Indonesia: Studi

Kasus tentang Perusahaan Subkontraktor di Daerah Surakarta dan Klaten [The Development of Subcontractor Systems in Indonesia: A Case Study of Subcontractor Firms in Surakarta and Klaten]’, Masyarakat Indonesia 12 (3): 253–74.

Thee K.W. (ed.) (1985), ‘Kaitan-Kaitan Vertikal Antar-Perusahaan dan Pengembangan Sistem Subkontraktor di Indonesia: Beberapa Studi Kasus [Vertical Inter-Firm Linkages and the Development of Subcontracting Systems in Indonesia: Some Case Studies]’, Masyarakat Indonesia 12 (3).

—— (1993), ‘Industrial Structure and Small and Medium Enterprise Development in Indonesia’, EDI Working Paper, World Bank, Washington DC.

—— (1997), ‘The Development of the Motorcycle Industry in Indonesia’, in M. Pangestu and Y. Sato (eds), Waves of Change in Indonesia’s Manufacturing Industry, Institute of Developing Economies, Tokyo.

Weijland, H. (1999), ‘Microenterprise Clusters in Rural Indonesia: Industrial Seedbed and Policy Target’, World Development 27 (9): 1,515–30.

Y

uri S

at

o

APPENDIX Characteristics of Sample Firms in Ceper

Firm Turnovera Assetsa Production No. of Activitiesb Major Products Period Present Owner

(Rp million (Rp million Volume Workersa Business

/year) /year) (tons/year) Commenced Gener- Year of Place of

ationc Birth Birth

A 62 42 n.a. 9 C Train brake components 1970s 2 1967 Ceper

B 42 90 10 10 C Ricemill components 1990s 1 1959 Ceper

C 360 150 420 11 C,M Pipe fittings 1960s 2 1953 Ceper

D 290 250 240 27 C,M,A Pumps 1980s 1 1955 Ceper

E 480 250 480 30 C,M Gear wheel 1980s 1 1950 Ceper

F 1,800 275 720 34 C,M,A Scale components 1950s 2 1966 Ceper

G 1,000 n.a. 35 35 C,M,A Machine components 1950s d d d

H 660 500 540 40 C,M Water pipes, pumps 1980s 1 1959 Ceper

I 540 540 480 40 C,M Antique chairs 1960s 2 1948 Ceper

J 720 350 840 40 C,M Ship components, manholes 1980s 1 1966 Solo

K 900 850 360 47 C,M Diesel engine components 1980s 2 1962 Ceper

L 1,200 2,000 360 48 C,M,A Machine components 1940s 2 1945 Ceper

M 650 1,200 n.a. 60 C,M,A Tractor components 1960s 2 1956 Purworejo

N 1,000 661 n.a. 70 C,M Telephone line components 1950s 2 1963 Ceper

O 2,200 1,000 1,380 80 C,M,A Pumps, ricemill components 1970s 2 1956 Ceper

P 1,500 1,200 n.a. 150 C,M,A Forklift components 1960s 2 1951 Pekalongan

Total 12,968 10,310 5,910 731

aTurnover, assets and number of employees are as of 1997 before the crisis. cGeneration is calculated from the establishment of the business entity.

bFor activities, C: casting M: machining A: assembling. dEstablished by the government, not privately owned.