®

Through the Shedding of Blood:

A comparison of the Levitical

and the Supyire concepts of

sacrifice

A comparison of the Levitical and the Supyire

concepts of sacrifice

Michael William Thomas Jemphrey

60

2013 SIL International®

ISBN: 978-1-55671-366-8 ISSN: 1934-2470

Fair-Use Policy:

Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair-use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s).

Editor-in-Chief

Mike Cahill

Managing Editor

LLB (QUB, 1981) BD (QUB, 1986)

THROUGH THE SHEDDING OF BLOOD:

A comparison of the Levitical and the Supyire

concepts of sacrifice

Thesis offered for the degree of MASTERS OF PHILOSOPHY

COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES

THE QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY, BELFAST

PREFACE

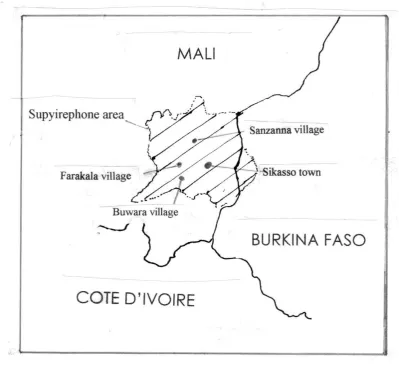

In 1992, my wife, Miranda, our two-year-old daughter, Shona, and I took up residence in the village of Kabakanha, which lies twenty miles west of Sikasso town, on the main road towards the capital of Mali, Bamako. We joined the SIL team that is working on linguistic and anthropological research, literacy and Bible translation among the Supyire people.

As the time approached for the move, the whole idea became daunting. But over the years, as together we learned the language, made a circle of friends and acquaintances, rejoiced as Stephanie was born into our little family, listened to the personal and family dramas unfolding around us, sought co-operation with church leaders and missionaries, studied and worked on producing written materials in Supyire, the sense of utter strangeness gave way to one of belonging. Of course, we will always be strangers, we will never fully understand, nor will our strange ways ever be fully understood here; but still, the place has become more and more like home for us.

Working on Bible translation, we have been confronted day in, day out, with the fact that we are not just translating from one language to another, but from one whole worldview to another. A simple word like “dog” seems easy to translate into Supyire. Pwun certainly designates the familiar four-legged creature, but what about all the differing connotations that the word may bring to the mind of the hearer? To

the Jews “dog” was a term used of the despised Gentiles. To the Supyire it may bring up images of a hunting animal, or of a bloody sacrificial offering to a fetish. Now

add in the complicating factor of a multiethnic team: for me, to call someone “dog”,

or even more so, a female of the species is most derogatory. A German colleague, on the other hand, assures me that Hund! can be used to compliment someone, for example for his intelligence.

Being on guard against possible mismatches in meaning is essential in the process of translating. In translating Jesus’ remark to the Gentile woman “It is not

right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs” it proved necessary to add

When it came to translating passages involving sacrifice, which is a rich and central theme both of the Bible and of Supyire life, the issues became all the more complex. Coming from a culture where animal sacrifice is not practised and is seen as alien, if not repulsive, I felt the need to gain a much deeper understanding of the concept in both the Hebrew and Supyire worldviews. It is primarily this which has prompted me to follow this line of research.

The dissertation was written over a two-year period. The first was on location in Mali, and the second during our home assignment in Belfast. It has been far from a one-man venture. As the Supyire proverb puts it, “One finger alone cannot lift a

pebble.” My present understanding of the Supyire view of sacrifice is thanks to the

help and co-operation of many within the Supyire community, and many outsiders who themselves have sought understanding of the matter. Particular thanks should go to:

Those members of the Supyire community who have given interviews about their sacrificial practices, and the role they play in Supyire life.1

The members of the translation and literacy team, who spent hours with me shedding light on otherwise incomprehensible words and events.

Our SIL colleagues, Joyce Carlson whose detailed anthropological journal of Supyire life over the years has been a veritable gold mine of anecdotes and insights, and Robert Carlson whose musings on the matter, as on any matter, invariably provoke further questions.

Emilio, who opened up for me the significant research on sacrifice, carried out by himself and others in the Roman Catholic community.

I am very thankful that God has surrounded us with extended family and friends in Belfast who, along with our home congregation, Knock Presbyterian Church, have supported and encouraged us unstintingly throughout our years in Mali. I was amazed and very grateful too to find a supervisor, almost on our doorstep in Belfast. Dr. T.D. Alexander, who has written on sacrifice in Leviticus, has given me

1It seemed clear that there were parts of their work they were willing to discuss and other parts “trade

the benefit of his experience, provided wise guidance and made timely, incisive comments.

A translation strives to communicate as fully as possible the original intentions of the author. Translators readily admit though that the subtle complexities of each language, the connotations, the play on words mean that they will always fall short of the ideal. When the translator has turned off his computer, the task of bridging the gap between the two worldviews must be taken up by others. My prayer is that this thesis may make a contribution not only to translation of the Scriptures into Supyire, but also to the understanding of the biblical and Supyire worldviews for those evangelists, pastors, and teachers who seek to communicate the translated Word of God to the Supyire people.

Note:

CHIEF ABBREVIATIONS

Biblical books

1 Sam 1 Samuel 2 Chr 2 Chronicles 2 Sam 2 Samuel 2 Tim 2 Timothy Deut Deuteronomy Exod Exodus Ezek Ezekiel Gen Genesis Heb Hebrews Isa Isaiah Judg Judges Lam Lamentations Lev Leviticus Num Numbers Phil Philippians Prov Proverbs Ps Psalm Biblical versions

GW God’s Word for the Nations KJV King James Version

LXX Septuagint

NASB New American Standard Bible NCV New Century Version

NIV New International Version NLT New Living Translation NRSV New Revised Standard Version REB Revised English Bible

RSV Revised Standard Version TEV Today’s English Version

(Biblical quotations are from the NIV unless otherwise specified.)

BDBG The New Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius Hebrew-English Lexicon fn. footnote

SIL Summer Institute of Linguistics

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ii

CHIEF ABBREVIATIONS v

TABLE OF CONTENTS vi

LIST OF FIGURES vii

1. INTRODUCTION 1

2. THE SUPYIRE PEOPLE AND CULTURE: AN OUTLINE SKETCH

6

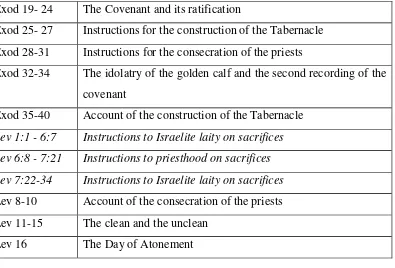

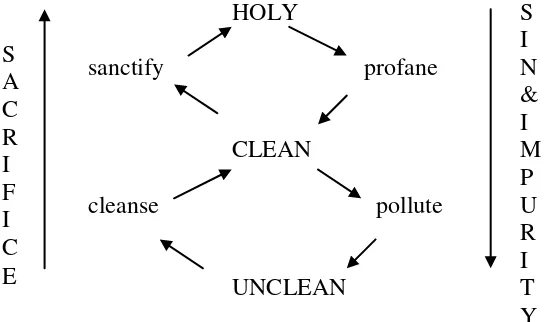

3. SACRIFICE IN SUPYIRE SOCIETY 28 4. LEVITICAL SACRIFICE IN RELATION TO HOLINESS 58 5. THE FIVE MAJOR SACRIFICES IN LEVITICUS 1-7 70 6. LEVITICAL AND SUPYIRE CONCEPTS OF SACRIFICE

COMPARED AND CONTRASTED

117

7. TRANSLATING LEVITICAL SACRIFICES INTO SUPYIRE 125 8. CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS 138

APPENDICES

A. HISTORY OF THE SUPYIRE PEOPLE 142 B. OCCUPATIONS OF THE SUPYIRE PEOPLE 145 C. THE SUPYIRE CALENDAR 146

LIST OF FIGURES

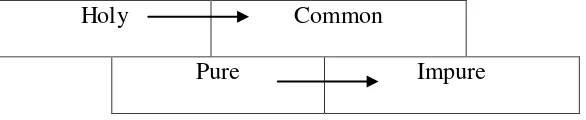

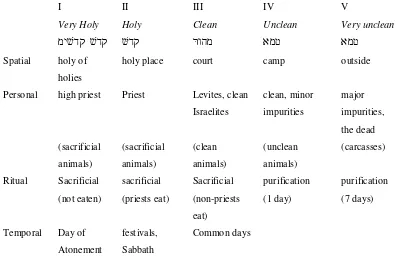

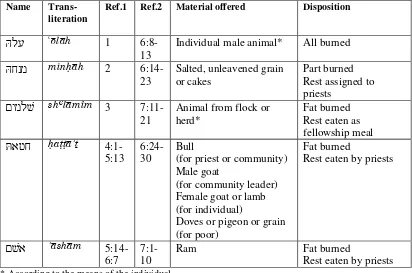

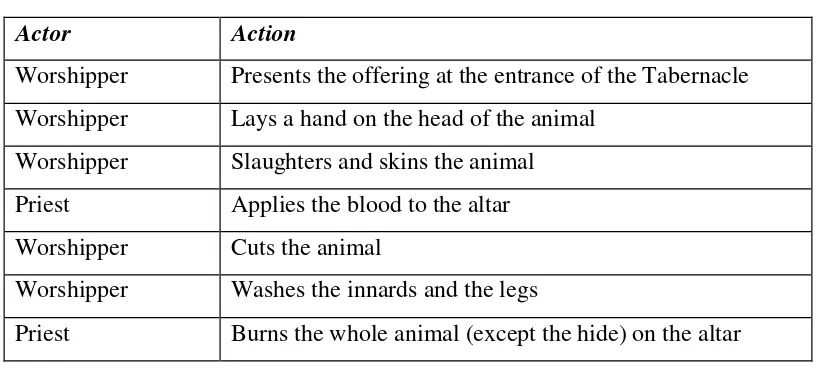

1. Map of North and West Africa 10 2. Map of Supyirephone area in Mali 11 3. Supyire vocabulary in the domain of sacrifice 54 4. Structure of Exodus 19 – Leviticus 27 58 5. Dynamics of sacrifice sin and infirmity in Leviticus 64 6. Dynamic categories of holiness and impurity 65 7. Gradations of holiness 66

8. Holiness spectrum 66

9. Five sacrifices in Leviticus 1-7: summary of their forms 70

10.The hlu ritual 71

11.The hjnm ritual 83

12.The <ymlv ritual 88

13.The tafj ritual 99

14.The priest’s actions in the greater and lesser tafj rituals 99

15.Tafj prescribed for different offenders 101

16.The <va ritual 108

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 THE THEME OF SACRIFICE IN HEBREW AND SUPYIRE

CULTURE

Sacrifice is offered on account of a birth, a marriage, barrenness, farming, family disputes, death; sacrifice runs as a thread through the whole of Supyire life.

From Cain to Abraham to Moses to Isaiah to the Lamb that was slain, the same thread can be traced through the Bible. The writer to the Hebrews comments:

“Without the shedding of blood, there is no forgiveness of sins” (Hebrews 9:23b).

But how similar are these threads? How do the Supyire people involved in sacrifice view what they are doing? What is the function of this ritual? How does it work? Apart from the superficial similarities, do these Supyire rituals have anything in common with the biblical ones?

These are important questions for the translator. “Wittgenstein pointed out that words do not carry meaning so much as they stimulatethe hearer’s thoughts into

the right channels”2

and a major hurdle in translation is that words which may appear similar may stimulate the hearer in a different culture to think along the wrong channels. The same thought is developed by Callow:

“Words do not relate to abstract definitions in our minds, but to experiential concepts. … In northern Ghana dogs are not associated with

leads, walks and parks, but fleas, hunting, and being cooked and eaten. Not only do word associations differ factually from one language to another ...

they differ also emotively. The Englishman’s affection for his dog is almost

incomprehensible in many cultures. … Unless otherwise trained, we associate the foreign word with our own cultural background, often with misleading consequences. We need to do exact and intensive studies in every aspect of meaning in order to counteract our intuitive and false assumption that other languages, although sounding different, are in other respects much like our

own.”3

2

Goerling, Fritz, Criteria for the Translation of Key Terms in Jula Bible Translations, Doctor of Philosophy Thesis; Fuller Theological Seminary, 1995, p.38.

3

Wendland4 outlines three steps necessary for taking into account these cultural factors in biblical translation:

1. exegesis of biblical culture 2. exegesis of receptor culture

3. comparing and contrasting the two cultures with the purpose of making any necessary adjustments in the translation.

This paper shall attempt to follow Wendland’s counsel and gain an in-depth understanding of the theme of sacrifice: a theme of fundamental importance both to the biblical message and to the Supyire people. As the topic of sacrifice in the Bible is too vast for a work of this size, this study needs to be limited. It will compare Supyire sacrifice with the system of sacrifices instituted in Leviticus 1-7, which is foundational for sacrifice in the rest of the Bible.

The understanding gained will inform preliminary proposals as to how the various sacrifices should be translated. Two caveats need to be entered at this point. Firstly, though comparing and contrasting the two cultures’ view of sacrifice is an

essential foundation, it will not automatically yield the “correct translation”. Van der Jagt stresses the need for creativity: “Translators must have an open and creative

mind and base their choices on research of both the biblical text and the culture of

the receptor audience in order to assure a faithful transfer of meaning.”5

Gutt stresses that it is both an analytical and an intuitive process.6

Secondly, the preliminary nature of any proposals presented herein needs to be emphasized. The work of translating the Scriptures is, in fact, never complete, as can be seen in the continuing work on translating into English six hundred years after

Wycliffe’s English Bible appeared. It would therefore be presumptuous to propose any definitive solutions in this paper, especially so as it will be completed outside the context of the Supyire community. As Gutt remarks, the comparative study should ideally involve representatives of the community for whom the translation is intended.7

4

See Goerling, Criteria for the Translation of Key Terms in Jula Bible Translations, p.82. 5

In Stine, Philip C. and Ernst R. Wendland, Bridging the Gap, African Traditional Religion and Bible Translation, UBS Monograph Series No. 4; Reading: United Bible Societies, 1990, p.150.

6

Gutt, Ernst-August, Relevance Theory: A Guide to Successful Communication in Translation; USA: Summer Institute of Linguistics and United Bible Societies, 1992, p.70.

7

The most that should be attempted is firstly, putting forward suggestions which will need to be pondered collectively by the translation team and tested in all sections of the Supyire community, and secondly, highlighting areas which will require further research.

A potential additional benefit of the study is that the comparison and contrasting of the two worldviews should inform discussion on the translation of other biblical key terms which relate to the concept of sacrifice, such as priest, altar, sin, atonement, guilt, temple, and tabernacle.

1.2 USAGE OF TERMS

Some scholars distinguish between the words “offering” and “sacrifice”. On the basis of their etymology, some contrast them by using “offering” to refer to the

presentation of a gift, and “sacrifice” as a presentation to a divinity. Others use the word “sacrifice” to refer to any “offering” that involves killing.

For the purposes of this paper we shall avoid making any distinction between the two terms. We are seeking to compare Hebrew and Supyire customs, and it seems simpler not to introduce English semantic divisions, which might confuse the

discussion. Hence, we will use “sacrifice” and “offering” interchangeably.

1.3 THEORIES OF SACRIFICE

For much of the 20th century it has been commonly held among ethnologists that sacrifice in religions throughout the world have evolved from totemic beliefs, in which certain animals are regarded as sacred and unable to be used as daily food. The totemic animal represented both the tribe and its god, and the ritual slaying and eating of this animal created a communion between the god and his people. Robertson Smith, for example, argued that since totemic practices call for ritual killing and eating of the forbidden animal, therefore sacrifice originated with these practices.8

This is however a non-sequitur, and in 1964, in their influential work

“Sacrifice: its Nature and Function”, Hubert and Mauss demonstrated the weakness

8

of the argument.9 They rejected the evolutionary schemes of their predecessors, and aimed rather to provide a general model applicable to all religious systems. For them, the opposition between sacred and profane is the foundation of all societies.10 Sacrifice is the means par excellence of establishing communication between the sacred and the profane worlds. Sacrifice is a rite of passage.

When a victim is consecrated, it becomes progressively divine. As it penetrates the sacred zone, it becomes so sacred that the sacrificer hesitates to approach it. But he must, as his personality and that of victim are merged. The killing separates the divine principle in the victim from the body, which continues to belong to the profane world. The sacrificer then performs an exit ritual to return to profane, and to rid himself of any contamination that he may have suffered in the ritual.

However de Heusch in his critique of Hubert and Mauss points out that their model suits Vedic Indian, but not necessarily the African or Indo-European contexts.11 There is a real danger in imposing a model from outside.

An example of how easy it is to fall into this trap of imposing a model is Evans-Pritchard’s study of the Nuer religion. If a Nuer man infringes an interdiction, he is in a state of nueer, kor or rual, depending on the circumstances.

Evans-Pritchard translated all three by the word “sin” and argued that sacrifice fulfils a

purifying and expiatory function among the Nuer. Indeed Evans-Pritchard himself clearly admits that these concepts have been imported from the Judeo-Christian

worldview: “I must confess that this is not an interpretation that I reached entirely by

observation, but one taken over from studies of Hebrew and other sacrifices, because it seems to make better sense than any other as an explanation of the Nuer facts.”12

Averbeck, surveying the different theories, comments that most

“have been both reductionistic (i.e. illegitimately reducing the diversity of

sacrificial phenomena to one rationale) and evolutionistic (proposing that all offerings and sacrifices evolved from one primal form). Scholars today tend to disregard the reductionist and evolutionary features and treat them as

9

De Heusch, Sacrifice in Africa, p.2. 10

De Heusch, Sacrifice in Africa, p.3. 11

De Heusch, Sacrifice in Africa, pp.3-4. 12

complementary rather than contradictory, suggesting that there appears to be some truth in all or most of them, at least in certain cultures.”13

In the light of the above discussion, I shall attempt to avoid the imposition of any model, but rather allow the biblical and the Supyire sources to speak for themselves. The Supyire people will speak through transcribed stories, texts and interviews. I shall seek to understand how they see sacrifice, and how it fits into their view of the world. I shall do the same for the biblical material, and then compare the two. It is clear that perfect objectivity is an unattainable goal, as the results are processed through the author whose own understanding of the world will inevitably influence what is selected as important and the way the results are presented. Nevertheless, this remains the best way for an outsider to gain a clear understanding of how the two different cultures look at sacrifice.

13Averbeck, Rick, “Offerings and Sacrifices”, in W.A. Van Gemeren (ed.)

2. THE SUPYIRE PEOPLE AND CULTURE:

AN OUTLINE SKETCH

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Traveling through the bush, we happened on a group of maybe thirty young people; most were wielding the typical heavy wide bladed hoe and attacking the task of ploughing the field. There was also a small group of musicians playing the drums and the balaphone,14 and there was one figure in the middle, wearing a smart hat, singing out encouragement to the workforce. They responded vigorously with what brought to mind a dance rather than any farm labour I have ever witnessed. Bent almost double over the earth, they jumped in time to the music first to one side of the furrow they were ploughing, then to the other, each time they landed cutting the blade into the soil with the weight of their whole body. There was definitely a party atmosphere in the air.

This little cameo captured the essence of Supyire life, of how the Supyire see themselves.

The Supyire see themselves tied to the earth

The pride and joy they feel in exploiting the soil is encapsulated in the songs such as that sung by the young man in the smart hat. The following is one such verse.

Sorcerer of the earth Old Robber Cultivator

Cuts the earth without pity Stirs the earth like a porcupine Crushes stones to dust

Morning Star among the farmers.

14

The Supyire are inextricably linked to their family

It is likely that most, if not all, of the young people cultivating together were from one large extended family. A united family, working and living together in harmony, is of the highest priority for the Supyire. The impossibility of success outside this context is expressed in a plethora of stories and proverbs such as:

You cannot lift a pebble with one single finger.

The fool says, “The family is not good”, but in reality, the family is more savoury than salt in the sauce.

A united family is defined as follows:

“They do the same work.” “They listen to one another.” “They follow the same customs.” “They eat at the same place.”

The Supyire are closely bound to the supernatural.

The name of God is never far from the lips of the Supyire. They will invoke his blessings at every occasion, such as:

Blessing Occasion

“May God sweep the road before you.” departure on a voyage

“May God make his mother’s milk sweet to him.” news of birth

“May God give you a lot back in its place.” the receipt of a gift

“May God open the morning.” good night greeting

To have access to God, one normally has to go through the channel of intermediaries who are closer to him than humans are: spirits who live in the bush, or ancestors who live in the village of the dead. The field I witnessed being ploughed belonged to one family who would pay the young people with an animal, which the young people would keep to celebrate the annual village festival. Then it would be slaughtered in honour of the bush spirits or ancestors, and provide a communal feast.

Summary

beings who inhabit the earth, and indeed with mother earth herself. Regular sacrificial gifts are essential to maintain these peaceful relations, and if for some reason the peace is broken, inevitably a sacrifice of some sort will be required to repair the damage and restore harmony.

2.2 THE SUPYIRE PEOPLE AND THEIR NEIGHBOURS

IN WEST AFRICA

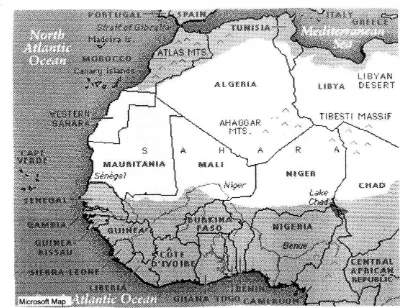

The Supyire people who number, according to some estimates,15 over 350,000, live in south-eastern Mali in the region of Sikasso (see maps, figures 1 and 2, pp.10-11). Their language, which also bears the name Supyire, is one of a chain of seventeen Senufo languages spoken in the savannah of West Africa stretching into Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana.

The Senufo language family can be divided into northern, central and southern branches. Supyire is one of the northern group which includes Minyanka (further north in Mali) and Sucite (across the border in Burkina Faso).16 These languages are closely related but have their own distinctive peculiarities.

The same can be said of their cultures. Despite many features in common with neighbouring groups, the Supyire can be said to have their own distinctive customs. Unlike their neighbours, the Minyanka,17 the Supyire do not practise sacrifices to God. Unlike the southern Senufo groups, they do not have secret societies.18 In our research, we have noticed variations on the theme of sacrifice even from one Supyire village to another.

The largest ethnic groups in the region are non-Senufo: the Bambara to the north and the Jula to the south, whose languages are closely related to one another. The Bambara have been dominant militarily and politically, while the Jula traders have considerable economic power. A large majority of both groups are Muslim, but

15

Grimes, Barbara F., (ed.), Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 13th Edition; Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics Inc., 1996, p.310.

16

Carlson, Robert, A Grammar of Supyire; Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1994, p.1. 17

Berthe, Pierre, La Religion Traditionelle chez les Minyanka, Abidjan, Institut Supérieur de Culture Religieuse, 1978, p.37.

18

their Islam often affects the exterior forms of their religion, while they remain at heart animistic.19

19

2.3 ENVIRONMENT

The region of Sikasso has been called the breadbasket of Mali. Certainly its environment is gentler on humans than the rest of the country. The terrain is forested and hosts series of gently undulating hills and a few plains.20 Since the soil is fairly fertile, much of the forest surrounding the villages has been cleared for agricultural purposes.

The average temperature over the year is twenty-seven degrees centigrade.21 The dry season is dominated by the harmattan, a dry warm wind blowing off the Sahara. Then in April, the humidity and temperature build before the rain is released in tropical downpours. The rainy season can last up to six months through to October.

2.4 EVOLUTION OF SUPYIRE SOCIETY

The ancestors have a great influence on everyday Supyire life. This factor acts as an effective brake on any rapid innovation in Supyire society. To break with

any tradition means doing things differently from one’s forefathers, which may well

displease them and provoke them to cause illness, accident or some other misfortune to the offending family.

For instance, the practice of excision of girls is continued to this day.22 Whatever the origins of the practise were, they are largely forgotten, and when asked why it is carried out, most woman reply that it is traditional.

Occupations have evolved with the introduction of cash. But farming techniques in advance of the traditional manual hoe were late to develop. It was not until the 1960s that the ox-drawn plough became established. Introduction of a cash crop like cotton, now widespread in the area, also took a long time.

It is in the realm of religion that tradition retains its greatest hold. Despite the pressure of living in a country where Islam dominates, and the fact that the Christian church has been established since the beginning of the 20th century, the large

20Coulibaly, Daouda and N’Golo Coulibaly and Marjike Loosvelt,

Panorama du Kénédougou; Bamako: Editions Jamana, p.4.

21

Coulibaly, Coulibaly and Loosvelt, Panorama du Kénédougou, p.6.

22Jemphrey, Miranda “Knives To Razors: Female Circumcision Among the Supyire of Southern

majority of Supyire remain outside the world religions and continue in the traditions of their ancestors. Many of those who do attend the mosque or the church are careful to fulfil their traditional religious obligations too. Probably Muslims are more openly syncretistic, and would sacrifice a lamb during the traditional village festival to the spirits. Church teaching would discourage Christians from active participation in the festival. Christianity is seen as a foreign religion. This is reinforced by the fact that a majority of church leaders are from other ethnic groups, having immigrated into the region, and that worship services have been held in Bambara, the dominant trade language.

A further restraint on innovation is the fear of being different. Anyone who is

seen as getting ahead of one’s neighbour is in danger of being the object of jealousy.

His neighbours will use sorcery or violence to reduce the gap. The story of Naba,23 reputedly the first Christian in Kabakanha, serves as a good illustration.

Va was a warrior renowned to have certain supernatural powers. It was said he could predict the future and that no metal object could penetrate his body. He was also wealthy in cattle. Jealousy of his riches meant that he was chased from one village to another, until he finally settled in Kabakanha.

At that time Protestant missionaries were also having a hard time finding a Supyire village which would welcome them and their message. Naba predicted that those who refused the whites would later come to admire them. Kabakanha then converted and became a predominately Christian village.

It is striking to note the ongoing effects of that decision today. Even though a large number of Christians later reverted to animism, the stranglehold that the fear of change held was broken. Today the village has become the major market town in the area, and boasts a dispensary, maternity, primary and secondary schools, and is seat

of the new mayor’s office for the area.

There is an ongoing struggle over the Supyire identity: education in French, migration of other ethnic groups into the region from the north of Mali, outside religion, development agencies introducing new technologies and modern communication have a tendency to squeeze Supyire language and culture to the sidelines, especially in public life. On the other hand, the Supyire remain proud of their identity, culture and language. Local radio stations which broadcast

23

programmes in the Supyire language and the continuing use of the language within the family mean that the struggle is by no means one-sided. While Supyire culture is no longer as static as it once was, it is adapting to change rather than disintegrating.

2.5 THE SUPYIRE COSMOLOGY

The Supyire world is alive and teeming with unseen forces and beings, benevolent and malign to varying degrees. Religion has to produce results; its goal is to harness enough power from what Joyce Carlson24 describes as the “Supyire

pantheon” to protect oneself from harm and make life a success. We shall see later how sacrifices are so vital in appropriating this protection and power.

Deity

Kile, the Supyire name for God, is the same word they use for sky. Kile is the Creator God, the source of all life. It is Kile that is in control of all that happens, good and bad, and is perceived more as a force rather than a person. In the face of a

death, people will say fatalistically, “God’s will for him has arrived.”

As he is the source of all blessings, throughout the day, people will wish each other good fortune, health and protection invoking the name of Kile. There is a vast variety of blessings which include:

“May God give you strength.”

“May God make the rest of the day pass well.”

“May God wake us up one at a time” (a night greeting: only in an emergency would

everyone wake up at the same time).

Nevertheless, Kile is seen as remote and inaccessible to humans. Escudero25 notes the following current Supyire expressions:

“Kile laaga a t››n.” God is far away.

“W… na j… a n› Kile na mî.” Nobody can reach God.

“W… na Kile cŠ mî.” Nobody knows God.

As Kile cannot be reached directly, people need to find intermediaries who do have access to him. As we shall see, there is no shortage of these.

24Carlson, Joyce “The Supyire Pantheon: A Comparison with the Central Senufo Pantheon”, Notes on

Anthropology and Intercultural Community Work 10 (June 1987) 3-15.

Supernatural spirits

There are different races of spirits who live in the bush country, outside of the villages. Those that commonly appear in folk tales are called the bush people. They have long hair, often blond, have white skin and backward turning feet. In one tale, they return home to a baobab tree after a day cultivating their fields. They bring firewood and put down their hoes. Then the hoes pick them up and put them down! So mixed up with the magical elements of the stories is the mundane, everyday life they lead. Living as they do in the wild, chaotic untamed bush, they are somewhat dangerous creatures, with potential for causing harm as well as good.

The Supyire have also adapted to the existence of jinas, which form part of the world of the neighbouring Bambara people, the majority ethnic group in Mali. Appearing less often in traditional stories than the bush people, less is known about the lives of jinas. Still, they probably wield the greater influence on the course of human life. One diviner said that the jinas need to talk with Kile before he agrees to send the rain. They choose certain people to be their instruments, and at certain times will take possession of them and give them powers, such as the ability to perform divination or play musical instruments during religious festivals.

Another race that live in the bush, are the w•rokolobii,26 known for their

evil deeds. According to Joyce Carlson’s research,27

they will shoot a person on sight, but fortunately they fall asleep very easily, and will sometimes even fall asleep before they are able to discharge their arrow. If you construct a corral or house near the home of one of them, they will eventuallykill all your cattle or family.

Also hostile towards humans are the faraüiwater spirits that can kill a person who falls into a stream, the body being left to float on the water. The Bambara too know this spirit.

A more benevolent spirit is your guiding spirit (nahafoo), otherwise known as your mîlîgî, a word borrowed ultimately from Arabic where it means angel. It will protect you, but can also punish you if it is neglected and does not receive sufficient sacrificial gifts.

26

A loan word from Bambara. 27Carlson “

Ancestors

The ancestors (kw—ubii, literally “the dead ones”) are those who lived long

honourable lives in society, and have contributed to the continuation of the race through marriage and children. They lead a village life of their own, raising herds and cultivating fields. The more importance a person gains in this life, the greater power he will wield as an intermediary when he has passed on to the village of the ancestors.

Particularly powerful among the ancestors are the spirits of twins. A woman who was both a twin and a mother of twins from a Senufo group in Côte d’Ivoire recounted a creation myth28 which explains their significance. “When [God] created the first man and woman, they became man and wife. When the woman conceived

for the first time, she gave birth to a boy and a girl, who were twins.”

The balance between male and female is important; twins who are of the same sex are a sign that something is out of balance and not seen so favourably. It is important to give the twins the same gifts; jealousy caused by unequal treatment would endanger the life and health of the family.

A small model made of two winnowing baskets joined together represents the

family’s twin spirits. When I took a lady who was having a long, difficult labour to

hospital, her family members brought along this model, presumably to help give a safe delivery.

Fetishes

Fetishes are man-made objects endued with supernatural power which families will often hang in a bag in the vestibule, entrance hut to their compound. Alternatively, they house it in its own little hut. Typically a fetish can be made out of

gold, or can be fabricated according to some “recipe”. Widespread among the

Supyire are fetishes called the Wara, the Kono and K›nr›. They get renowned for having certain powers. For example, the K›nr›, known as the fetish of love, can help to consolidate the love between a man and a woman and be used to produce a product which will increase the fertility of one’s fields.

As a certain fetish gains a reputation, people will copy its recipe to make their own fetish that will bear the same name. Often lesser known fetishes with different

28

powers will be brought and added to the bag and assimilated to the main fetish, so that if the contents of each K›nr›, for instance, were now examined, they would not be identical.

The power of the fetish is greatly feared, for the owner can use it not only to seek his own good, but also to harm others. Or it can be used as a sign of one’s power. The story is told by Nawara Sagoro that when Tieba was king of Sikasso in the 19th century, a certain renowned Senufo fetisher and warrior among the king’s troops, Namon›, used his tail fetish to bind the king and his court. In sacrificing to

the fetish, reciting the name of the king, he “tied” them, thus enabling Namon› to go

right into the king’s bedroom, shave his head, and escape without waking anyone.

This occurred on three separate occasions, until the king suspected Namon› and arranged for him to be killed in battle by his own side.

The power of the fetish is also used to serve as a policeman and judge in a small village community. In the case of a theft or suspected adultery, the wronged party will consult the owner of the fetish and ask him to harm or kill the offending party.

Every year the owner will organize a celebration in honour of the fetish and maintain good relations with it. Someone will don a mask and a particular outfit to personify the fetish and dance. The fetish mask will also come out to dance at the funeral of its owner. It is often forbidden for women to see the fetish or its mask.

Life force

Robert Carlson29 writes that every living thing in Supyire cosmology is

“endowed with a kind of impersonal life force called ¤…m…. This force can

harm other animals or things and is thus potentially the cause of disease and even death. Certain animals and people, such as pythons and albinos, have more ¤…m… than others. You can get sick even by walking past the place where a python has been coiled up, even if it is no longer there. Hunters must protect themselves in various ways against the ¤…m… of their prey. Soldiers and policemen, too, who may kill someone in fulfilling their duties, are also subject to attack from the ¤…m… of their victims.”

Conclusion

Although tradition holds great weight among the Supyire,30 it would be wrong to give the impression that they hold to an unchanging body of orthodox doctrine. What is outlined above should only be taken as a rough guideline of beliefs. Many of the details are somewhat vague, and the lines blurred. So in one conversation Robert Carlson recorded between two old men, one of them is heard arguing that Kile and the jinas are one and the same. In the mind of one diviner interviewed, jinas and bush people were the one and the same.

The same blurring can be seen in that the same word kile has three meanings: First, the Creator God is Kile. Second, the sky is called kile. And third, if you find anything considered extraordinary in nature, such as a skin shed by a python,31 or the nest of a rare bird (called kileükuu, God’s chicken) or two chameleons mating, you can take them home, and they become a kile. They are considered as a manifestation of God, and have supernatural powers. This little kile can receive sacrifices like a fetish, but it is more the god of an individual or a family, and as such has less influence on the community as a whole.

29Carlson, Robert “External Causation in Supyire Culture”, Notes on Anthropology 3:3 (1999) 7 -14 p.11.

30

See above, p.12. 31

A woman named Siri, hearing that a man had found a snake skin exclaimed “U a kile ta!” which can

In the 1950s a new religion involving a powerful fetish swept through the area. Before a village could adopt it though, it had to get rid of certain other fetishes, and a considerable number were burnt. So, despite the weight of tradition, when the Supyire have encountered something new which proves itself to be powerful, they have adapted it, and then adopted it into their own unique pantheon.

2.6 THE ROLE OF THE INTERMEDIARY

The importance of an intermediary in Supyire life is not restricted to dealings with the supernatural. If a Supyire travels to another village for business of any form, he needs to go through his intermediary, called a jatigi. The jatigi is responsible for housing and feeding the guest if he is staying a while. He will go with his guest on

whatever business he is intent and will repeat his guest’s words to the third party,

even if they have been already been clearly understood.

Once the relationship is established it is usually life long. “To leave a village is better than to change jatigi” is a proverb that expresses disapproval of the

fickleness of someone who changes from one intermediary to another.

Another important relationship is that of narafoo (plural: narafeebii). A person is a narafoofor his or her mother’s home village. A narafoo does not reside

in his mother’s village, since at marriage, it is customary for the bride to come to live in her husband’s village. The word nara has as its primary meaning “to lean away

from”. These are people who are obliquely related to the mother’s patriclan, related

to it, but leaning away from it, as it were. The narafeebii in the village of their

mother’s patriclan are always treated indulgently like children, no matter how old they are. At the same time, they are frequently given the role of mediator in matters of ritual or dispute.

In resolving a dispute, one can call on the services of a narafoo. If it is a particularly serious dispute, one may need others who are totally outside the family, such as members of the castes the blacksmiths and griots, or the Fulani, a light skinned nomadic race who herd cattle across West Africa.

In the most serious cases, one might have to resort to requesting the help of a

zìükunü› (plural zìükunmpii). There are traditional links between those bearing certain surnames; for example, the Sagoro and the Bogodogo families are

Zìükunmpii are expected to insult and banter each other (for example, accusing them of eating green beans). The only time there are any serious dealings is when one is called on to come and help resolve a family dispute. Immediately the reconciliation has taken place, the zìükunü› insults all the parties, left, right and centre, and then gets on his bicycle and leaves the village without a further word to anyone.

2.7 LIFE CYCLE OF A SUPYIRE

Birth

Oftentimes, a woman will seek supernatural help in order to conceive. Although Kile is the source of life, each child is thought to have come from a certain

place. So, if the mother had prayed for a child from the family’s little god kile, she might well name him Kilen› “God-man”; if from the fetish of love the K›nr›, the child may be named K›nr›cwo “K›nr›-girl”.

The child is actually not usually named until he has survived the first week, probably due to the high rate of infant mortality in the past. At the naming ceremony, he is presented to the ancestors of the village, who then take note of him to protect him and to keep him from straying from traditional ways.

If a mother loses a succession of two or three babies, it is said that it is the same child that keeps returning. The jinas are blamed for the death of some children, especially beautiful children they are thought to want for themselves. In order to try and deflect the attention of the jinas away from him, the child following one who has

died in infancy may be given a name such as “Ugly child”.

So there is some belief in reincarnation, but it is not clearly defined, and does not play a central role in Supyire thought. A child born into the family of an elderly person who has recently died is sometimes named after him.

Circumcision

Africa can be seen as a sort of sacrifice,32 but this does not appear to be the case among the Supyire.

Marriage

This is the rite that fully establishes an individual as a full-fledged individual in society. One must marry outside the family clan. The wife will invariably come to live in the village of her husband. Indeed it is the norm for the husband to build a hut

for her in his own parent’s home compound. So he will not move away from his family.

A series of long negotiations over the years between two clans culminate with

a family delegation from the groom’s side making an overnight stay in the village of

the bride. They stay with their jatigi who then as intermediary goes with the

delegation to bring greetings and gifts to the girl’s family. Kola nuts, cloths, cooking

utensils and two chickens to sacrifice to the ancestors are among the obligatory gifts. There is also usually nowadays a cash dowry. After friendly banter over the quality

of the gifts, the bride’s family provide a communal meal to seal the alliance between the two families.

Consistent with the third party nature of most dealings in Supyire society, the couple to be married is at no point involved in the negotiations. They are not even in the village on the wedding day; the girl will already have left to take up residence in

the groom’s village the previous day. They are strictly forbidden to eat any part of

the communal wedding meal, even leftovers.

The marriage is only really seen as consummated with the successful arrival of the first child. At this point they have fully entered into the ageless stream of family life, by contributing to its ongoing existence and expansion.

Married life

Men and women tend to live very separate lives. The men eat together first and then the women and children. There is a fairly rigorous division of labour. For

example, it is the husband’s responsibility to provide the staple for the meal: corn,

32

millet or rice. It is the woman, no matter what her husband’s means might be, who has to work to provide the tomatoes, spices and other condiments for the stew.

Divorce is fairly rare. The families, having invested so much in the marriage and the family alliance, will seek to ensure that it is successful. So although a wife

may be mistreated, and may run back to her parents’ home, in most cases attempts at

reconciliation will bring the two together again. There is little alternative. There is no role for a single woman in society. She has no means of obtaining an independent income. The children of the marriage belong to the family of the husband: it is they who have paid for the wife and the offspring of her womb.

On the other hand, if she is widowed, it is the husband’s family who has the responsibility to take care of her material needs, and provide her with a younger brother or cousin as a husband. Any offspring of this levirate marriage are considered

as belonging to the deceased brother’s family. If he has not already done so, the younger brother in such a case still needs to get married himself to another woman to be a fully fledged member of society.

It is rare to see a woman enjoying an idle moment. From dawn to dusk, they have responsibilities: collecting firewood, drawing water, heating it for bathing, pounding flour, cooking, tending the youngest and working in the fields. A good wife does all this for her husband without complaining, and above all, bears him many children. The joy for women, as for men, comes in working together in harmony, and sharing the chores with the members of the extended family.

Polygyny is still practised, somewhat less now than in time of warfare that claimed the lives of many men. The principal reasons for taking more than one wife are said to be:

1. If your first wife is unable to bear you children.

2. If your first wife becomes very sick or an invalid and can no longer work, or cook or satisfy your sexual needs.

3. If your first wife dies, even if she has given you children, and you are still young, you should marry again because of your own needs.

Funeral

with a series of rites, including wrapping, washing, and dancing the body, and giving it its last meal before burying it in the graveyard outside the village.

Then there is the wake, a feast-cum-celebration, the size and extravagance of which reflects the age and importance of the deceased. Such a send-off, properly performed, will ensure him or her a good welcome in the village of the ancestors.

The wake does not always take place immediately after the burial. There can be a delay of months or even years. The timing depends on the family having the grain and the money and the willpower to organise it. But for as long as it is not carried out, no one else in the family can receive his wake; moreover the

reorganisation of the family’s responsibilities cannot take place. Only when the wake

of the family is finished, can the authority of the deceased be devolved to the next in line.

As Joyce Carlson33 observes, the nightmare scenario is a “bad death”. If a person dies accidentally, by falling out of a tree, by snakebite, by suicide or murder, or in childbirth, or out in the bush away from their home, then they are a sinarbu, and as such, receive a hasty, insulting burial. It is said that if they are shown honour in their burial, their spirit will bring bad fortune back on those who buried them. The body is not washed or dressed in grave cloths. Nothing is done for it. The grave is dug right beside the body where it lies. The ditch is filled with thorns. Those burying the body turn their backs to it, and roll it backwards with their feet pushing it into the grave. Finally they cover it with earth.

There is, though, a way of at least partially redeeming this shameful situation by ensuring that the departed does integrate into the village of the ancestors and is not left homeless and dangerous. For someone who was married and would thus have

had a full ceremony if he had not met a “bad death”, the family can organise for the

sinarbu to be transformed. That is, they go to the cemetery in the middle of the night with a flute player who calls for the soul of the deceased, and then a hunter fires off a rifle round to indicate that the soul has come. Then they wrap a bamboo pole (to represent the body) in burial cloths, and bring it back into the village. There they go through the whole burial ceremony and wake with the pole, just as though it were the body of the deceased.

Another case of “bad death” is when a child or young person dies unmarried. After the burial there is no wake. But at some stage there will be a ceremony to integrate him into the village of the ancestors. If there is a death in his family soon afterwards, the ceremony for the youth will be carried out quickly during this fuller funeral. Otherwise, on the third day of the village festival, a collective wake is carried out along with the music and feasting for all youth, children and aborted babies who have died since the last festival.

2.8 VILLAGE AND BUSH

The Supyire world is divided in two: the village and the bush. The village is home, a safe sanctuary surrounded by the wild bush, inhabited by dangerous animals and spirits. Animals fall into two categories: bush animals and domestic animals. The bush becomes even more sinister at night, when the little bush people are out and about. People hesitate to venture outside the bounds of the village in the dark.

The shape of the traditional village reflects this need for protection. All the family compounds are enclosed behind the village walls. There is one sole entry to the village and to get to any particular family home requires knowledge of the sinuous paths that connect all the compounds. I have known even Supyire friends to get lost in a small village with which they were not too familiar.

At the entrance is found the village vestibule. The vestibule is easily distinguished from other huts, as it alone has two doors that enable it to serve as an entrance passageway. Being the sole point of entry, it is naturally the focus of efforts to defend the village from outside dangers, visible and invisible. Any enemy assaulting the village would be met at the vestibule by a battery of bows or rifles. The vestibule also houses a series of magic charms to ward off any evil spells aimed at penetrating the village. This is also where the elders of the village meet to make decisions, and negotiate with outsiders. They meet here too with the ancestors and perform various sacrifices to them.

2.9 THE EARTH

The Supyire have an intimate relationship with the earth, as it is ancient and the source of all fertility. They receive children from spirits living in a certain sacred spot on the earth. They live in huts made from the earth, farm on it with tools fashioned from metals drawn from the earth. Finally they are buried under the earth. Traditionally the grave is dug with two holes connected by a tunnel. Before the body is laid to rest in the tunnel, the children of the deceased crawl through the tunnel to

see their parent’s home.

The sacred nature of the earth is seen in that land cannot be bought or sold, but can only be used by permission, and that certain acts can spoil the earth. In that case, rain will not fall until the spoilt earth is repaired.34

2.10 FAMILY UNITY

“It is through a crack in the wall that a cockroach enters.” “One hand cannot wash itself.”

Many proverbs, like the two above, and folk tales express the ideal of unity, solidarity and co-operation in the Supyire family. This is a concern common throughout Africa. Grebe and Fon write,

“The greatest moral value that the head of the family tries to uphold is

UNITY. Within society each extended family is in opposition to other ones. Dealings between families are regulated by the influence a given family has within society. The larger a family, the greater its chance to make its influence felt. But if the family members are not united, the group is weakened. The head of the family will, therefore, always strive for two things: (1) to increase

the number of his family; and (2) to have his family united.”35

One is automatically expected to feed and lodge any member of one’s

extended family who arrives at one’s home for as long as they care to stay. The desire for unity is seen too in the process for making decisions. The men will gather to discuss a given problem. The youngest will be given the first chance to speak.

34

See below, p.44. 35

Then each in his turn, from the youngest to the oldest, will speak. Finally, the eldest,

the chief makes the decision. The wise chief, having taken into account everyone’s

point of view, will make his decision and attempt to please everyone, thus guarding the peace in the family, at least on the surface.

The flip side of this stress on unity is that individualism is not readily tolerated. Families that install themselves outside the main village are regarded with suspicion. I have heard of one village where anyone who might become a Christian has been threatened with death. Malana Sagoro recounted the story of one man, whose only son married a Fulani girl, adopted a Fulani name and Fulani customs, and herded cattle as a Fulani nomad. The father insisted that his son return to Supyire ways. The son refused. When the son died prematurely, the father said that he had asked the ancestors to punish his son.

The village is also seen as a large family, with a similar decision-making process. In Kabakanha, for example, there are three main families all with the same surname, two of which are descended from the two brothers who founded the village. The third is descended from a slave family, and its members do not have the right to become village chief. The chiefdom is handed to the oldest man within the two

“free” families.

At a national and international level, the Supyire identify themselves closely with others in the Senufo language family, but generally keep a distance from other ethnic races. In the town of Sikasso, where the Supyire are the largest ethnic group, they have their own political party, though they cannot command an overall majority in the local legislative body. If a dispute arises, the preference is to resolve it internally within the family or at the village level, rather than bringing them to the attention of the civil authorities.

2.11 CONCLUSION

“The stranger’s eyes are wide open, but he doesn’t see anything.” This

bush, fear of the spirits, fear of the ancestors, fear of the dark, fear of suffering a bad

death, fear of the unknown, and even fear of one’s closest family and neighbours.

Coulibaly36 comments: “The Senufo appear to us profoundly religious and superstitious, paralysed by fear of invisible forces with occult powers, which they have to deal with day in day out, in all their undertakings. It is that which explains

the multitude of sacrifices, offerings, and consultations with the diviners ... ”

In this chapter we have painted broad brush a picture of Supyire society, with the hope that it will help the reader to understand the role of sacrifices, to which we turn in detail in the next chapter.

36

3. SACRIFICE IN SUPYIRE SOCIETY

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Arriving in the centre of Wabere, the most ancient of all Supyire villages, one sees a very old tree, said to be sacred, under which all the sacrifices are made during the annual village festival. There is a huge, crescent-shaped, cement sitting area where the men relax and chat, curving around under the tree. Nearby are two small huts consecrated to the Wara fetish,37 and a mound streaked white from the flour paste poured on it in offering.

The importance of sacrifice in Supyire society is illustrated by the centrality of these sacrificial sites. The diversity of sacrifices will be seen in the wide variety of reasons for which people carry them out; for the present they can be summarised under the following general headings:38

1. To make requests for the future

2. To maintain good relationships with the supernatural realm

3. To gain knowledge

4. To deal with problems in relationships in the extended family

5. To ward off evil

6. To punish a wrongdoer

7. To gain power through sorcery

8. To dedicate some object or place to the jinas.

The most common and typical sacrifices are those carried out at the annual village festival seeking blessings on the year ahead. In order to give some insight into the rites, the words spoken at a sacrifice at the annual village festival at Sarazo village are set out below. This was the first of thirty-one sacrifices brought during the festival.

“Hear what the elders have to say.

This is the offering for the new year even today.

37

See p.16. 38

Make the village stand by the mortar, make the village stand by the pestle, even today.39

Give the village millet. Give the village more people.

Seek to make the village prosperous.

May our village not be dependent on any other. Multiply the population.

May every visitor who comes to the village with a sincere heart, even today, help him during the day, help him during the night,

so that he may be well thought of. And our village may be well thought of.

We, the people of Sarazo,

if we were without the difficulties which beset us today, could help out another village.

Another village would not have to take care of giving us millet. That should not have to happen.

This is not boasting.

Another village should not have to look after us. That would be shameful.

Give us a good rainy season…

O yes, give us a good rainy season.”40

In looking at Supyire sacrifice, we will start (in 3.2) by describing the surface forms by answering the following questions. To whom are sacrifices made? Who makes them? What is sacrificed? When are sacrifices made? Where are sacrifices made? On what are sacrifices made? What steps are performed? We will refer to

Escudero’s analysis of the village festival as a starting point in answering these

questions.

39This expression “Make the village stand by the mortar, make the village stand by the pestle” means:

“Give us women and millet; for without women and millet the sound of the mortar dies out, and the

village cannot stand.”

Next we will go below the surface (in 3.3) and seek to explain the functions of the sacrifices, why are they made?

At that stage we will probe deeper (in 3.4), exploring how these forms and functions fit into the rest of the Supyire view of the world, and how they are seen to

be effective, how they believe sacrifice “works”.

We will conclude the chapter (3.5) with an overview of the vocabulary the Supyire use in the domain of sacrifice.

3.2 SUPYIRE SACRIFICE: THE FORM

To whom are sacrifices made?

Any supernatural being who is perceived as being in a position to help or harm is a potential recipient of a sacrifice. During the village festival, the village ancestors and the village jinas receive particular attention. The ancestors are concerned that they continue to be remembered and honoured by their descendants. The jinas are seen as the erstwhile owners of the earth with whom the founders of the village made an alliance: in return for being allowed to settle on the land, the villagers make sacrifices to the jinas.

An exception is that the Supyire do not sacrifice to God, at least not directly. He is seen as too remote to intervene directly in everyday human affairs, and is not

interested in the sacrifices of men. “God does not eat our food” is a Supyire

expression that reflects this idea.

God is regarded as the ultimate source of all blessings, but since life descends to the living via the long line of ancestors and by the mediation of the jinas, it seems normal to re-ascend to God by the same pathway. Nawara Sagoro stated that in any sacrifice, to any god, spirit or fetish, inevitably part of the prayer associated with it is

“Kile u fara” which means“May God come and add to this.”

In one prayer recorded, the sacrificer to the jinas said, “Here is the sacrifice

for Dasu. Her son’s wife has passed away. Pingo’s wife has also passed away. So she

has come with this request: If God could give new wives to these two men, she will come and thank them [the jinas] with food.”41

Who makes sacrifices?

Any individual, man or woman, family or group (such as the village elders), can bring an animal or other offering for sacrifice for a specific reason. But the actual killing of the animal or presentation of the offering will be made by the person who has a special relationship to the recipient of the sacrifice. The oldest man in the ruling extended family is the closest to the ancestors and is thus responsible for the sacrifices. A fetish owner will sacrifice to that fetish. While a woman may bring an animal for sacrifice, only a man will ever kill it.

There is no formal ceremony to consecrate someone to the office of sacrificer, but in a society where relationships are constantly being monitored, it is widely known who fills which role.

What is sacrificed?

By far the most common sacrifice offered during the village festival consists of a chicken. Of the thirty-one sacrifices made during the Sarazo festival, twenty-five included a chicken, one was a bull, three were of staple foods, one of kola nuts, and two included money. Only those traditionally considered as domestic animals are acceptable as an offering.

The size and value of the sacrifice is important. A fully mature two-year-old cock is considered a better singer and a more valuable sacrifice than a young one. On one occasion, a large chicken had been promised, but only a small one was available, so the difference was made up by adding 100 francs.

There is enough evidence from various sources to affirm that in the past human sacrifices were made.42 In order to establish a market in a village, a girl had to be buried alive. In place of this, in 1985, the village of Kabakanha asked its pastor to

say a prayer for its new market. In sacrificing to a fetish, dog’s blood is now

accepted where once human blood might have been required.

Different members of the pantheon require different sacrifices. Nawara Sagoro, in conversation with Joyce Carlson, stated that the most common offering to

42

twin ancestors was kola nuts, followed by millet paste, money, chickens, and cowry shells.

Another sort of offering which is also called a sÃraga, the general Supyire word used for sacrifice, is that of cloth. These are not burnt or eaten, but are often given away, often to a poor stranger. Alternatively, a cloth of a certain colour or with a particular design is to be worn by the offerer.

When are sacrifices made?

The annual festival, seeking blessing on the year ahead, generally lasts a week and is usually held near the beginning of the rainy season. There is, though, no fixed date and each village will hold its festival on a different week at the discretion of the chief.

Individuals or families who have links to a particular jina or fetish will often hold a celebration and make a sacrifice annually to keep up the relationship.43 Otherwise, the sacrifices will take place whenever a problem or situation demands it. If someone is dogged by misfortune, for example some illness, he will consult a diviner, who will use some method—throwing cowry shells, reading palms, slapping of the thigh, or hitting a calabash full of water44—to diagnose which divinity or ancestor has been offended, why he is causing the illness, and what sacrifice should be offered as appeasement.

Where are sacrifices made?

The different spirits in the Supyire pantheon live outside of the village—in the fields, trees and rivers. That is where the sacrifices offered to them take place. There is often a sacred spot, sometimes marked by an unusual geographical feature, where they reside: in the village of Sarazo it is a dense thicket, whose trees must not be cut, where the original alliance between the founding fathers and the jinas was made. In Ifola, there is a pool with sacred fish that should not be eaten; in Kabakanha, a large flat solid rock; and in Misiricoro, an unusual grotto. In each case,

43

Diarra, Niara, Le Pori, Une Fête Traditionelle en Milieu Senoufo, Mémoire de Fin d’Etudes à

l’Ecole Nationale d’Administration, Bamako, 1996, p.19.

44Carlson, Robert “External Causation in Supyire Culture”,

the Supyire make contact with the divine through sacrifice in a place in the earthly, natural world marked in some way as out of the ordinary.

By way of contrast, if a particular jina has an intimate relationship with an individual or family, it may require that a hut be built, smaller than the huts used for human residences, which will be where it lodges and receives sacrifices. Fetishes often have similar diminutive huts.

The ancestors receive their sacrifices in the village vestibule that is their meeting place with the living.

On what are sacrifices made?

As noted above,45 the Supyire have an intimate relationship with the earth; it is seen as the symmetrical counterpart of the sky, (which itself is associated with the supernatural.)46 So the earth is seen as a suitable place for the cult. It is usual for the victims to be sacrificed on a simple altar of a pile of large stones, or of earth packed together into a half wall two or three feet high.

What steps are performed?

The typical pattern for a sacrifice is as follows:

1. An introduction: whoever brings the offering will let his intentions be known to the sacrificer by way of an intermediary. The intermediary then takes the chicken or other offering and, naming the person who has brought it, passes it on to the sacrificer, who performs the remaining steps.

2. The offering is presented, with some appeal to tradition such as, “This is the

offering from X on the path of the new year,” or to the name of someone who has

performed this before. Thus it is shown that it is not something new which is being done, but there is an authoritative precedent for it.

3. A prayer is made for specific blessings for the offerer. The name of God or some

other supernatural force is often invoked. The expressions “God is more powerful than all,” and “Every good person says God and every bad person says God” are

commonly heard. Malana Sagoro explained this by saying that this adds power to the sacrifice.

45

See p.25. 46

4. The throat of the victim is slit, and its blood is pou