Kuldeep Kumar Arti Bakhshi ABSTRACT

There has been increasing research in the field of a class of discretionary and spontaneous behaviors that are beyond explicit role requirements, but that are essential for organizational effectiveness. Smith et al. (1983) conceptualized these contributions as ‘Organizational Citizenship Behavior’.

Almost all the measures used for measuring OCB are developed in a western cultural context. The aim of the present study is to develop such a measure for Indian culture. The research design involves three broad stages: Item generation, scale development and assessment of reliability and validity of the scale. Full-time employees of various service organizations participated in the study. It is expected that the scale will serve as a useful tool for researchers and practitioners in the field of organization behavior.

Keywords: organizational citizenship behavior; reliability; validity; India

INTRODUCTION

From the time when Katz (1964) introduced the concept of a class of discretionary and spontaneous behaviors that are beyond explicit role requirements, but are essential for organizational effectiveness, there has been augmented research exploring the nature of such behavior. Smith et al. (1983), conceptualized these contributions as ‘Organizational Citizenship Behavior’ (OCB), later defined by Organ as ‘individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization’ (Organ 1988, p. 4). Since then, several associated concepts of OCB have been proposed and examined, including extra-role behavior (Van Dyne et al. 1995; Van Dyne & LePine 1998), civic citizenship (Graham 1991; Van Dyne et al. 1994), prosocial behavior (Brief & Motowidlo 1986), organizational spontaneity (George & Brief 1992), and contextual performance (Motowidlo et al. 1997).

The concept, nature and measurement of OCB has been derived historically from three sources (Farh et al. 1997). First, is the taxonomy offered by Katz (1964): The taxonomy is cooperative activities with fellow members, actions protective of the system, creative ideas for improvement, and self-training for increased individual responsibility. The second source (Smith et al. 1983) is the dimensions found by interviewing the lower-level managers, which yielded two major factors: altruism and compliance. The third source is the classic Greek philosophy that suggests ‘loyalty’ and ‘boosterism’ as significant forms of OCB, but also argues for the importance of principled dissent from organization practices and challenges to the status quo (Graham 1991; Van Dyne et al. 1994). The alternative perspectives afforded by

these sources have, not surprisingly, yielded overlapping but far-from identical categories and measures of OCB (Farh et al. 2004).

It is worth noting that all of three sources or perspective mentioned above have emerged in Western, usually North American, cultural context. Not much is known about the meaningfulness and validity of OCB concepts and categories in other social and cultural contexts. With the exception of Farh et al. (1997) and Kumar (2005), the current concept of OCB and its related measures have all been developed in a Western socio-cultural context. It is not known that the current dimensions of OCB as identified in the Western literature do exist in other cultures as well. George and Jones (1997) note the importance of contextual factors as shapers of OCB. Some potentially important contextual factors such as industry, technology and job function, have been reviewed by Organ and Ryan (1995), but with inconclusive findings. Such contexts might pervasively condition the nature, meaning, and importance of various forms of OCB. We do not know whether OCB as we now think of it would reflect the same dimensionality in a different societal culture or in a different system of economic organization.

Van dyne et al. (1995) and Podsakof et al. (2000, p. 515) note that the existing literature has mostly focused upon relationship of OCB with other constructs, rather than focusing upon the nature of the construct and its measurements per se. Schwab (1980) illustrated that such an imbalanced approach to research may generate a literature that turns out to be futile in the long run. Van dyne et al. (1995) also express similar views. Thus, establishing construct validity of OCB is an important research issue in itself.

Current status of OCB measurement

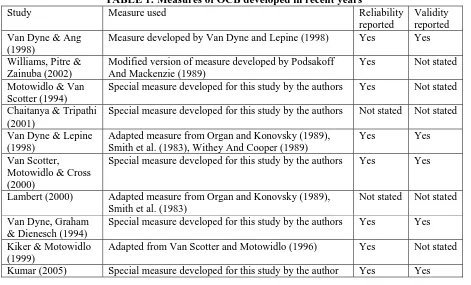

Various measures of beneficial non-task employee behavior have been used by the researchers; however, the literature does not offer an extensive evaluation of such measures (Kumar 2005). Table 1 below lists some of the measures developed in the recent years.

TABLE 1: Measures of OCB developed in recent years

Study Measure used Reliability

reported

Validity reported Van Dyne & Ang

(1998)

Measure developed by Van Dyne and Lepine (1998) Yes Yes Williams, Pitre &

Zainuba (2002)

Modified version of measure developed by Podsakoff And Mackenzie (1989)

Yes Not stated

Motowidlo & Van Scotter (1994)

Special measure developed for this study by the authors Yes Not stated Chaitanya & Tripathi

(2001)

Special measure developed for this study by the authors Not stated Not stated Van Dyne & Lepine

(1998)

Adapted measure from Organ and Konovsky (1989), Smith et al. (1983), Withey And Cooper (1989)

Yes Yes Van Scotter,

Motowidlo & Cross (2000)

Special measure developed for this study by the authors Yes Yes

Lambert (2000) Adapted measure from Organ and Konovsky (1989), Smith et al. (1983)

Not stated Not stated Van Dyne, Graham

& Dienesch (1994)

Special measure developed for this study by the authors Yes Yes Kiker & Motowidlo

(1999)

Influence of National Culture on OCB

As discussed, almost all the measures used for measuring OCB are developed in western cultural context, especially U.S., and culture does influence the conceptualization of specific behavior that might be considered OCB. Conceptions of what constitutes extra role (or citizenship) behavior vary across cultures. Lam, Hui and Law (1999) found that a five-factor structure of organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs)—altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, courtesy, and sportsmanship—was replicated in Japan, Australia, and Hong Kong. However, Japanese and Hong Kong employees were more likely to define some categories of OCBs (e.g. courtesy, sportsmanship) as part of ‘in role’ performance as compared with Australian and U.S. employees. Similarly, Farh, Earley and Lin (1997) developed an indigenous OCB measure in Taiwan and found that although altruism, conscientiousness, and identification qualified as etic dimensions of OCB, sportsmanship and courtesy were not found to be part of the OCB construct in the Taiwanese sample. There were also etic dimensions such as interpersonal harmony and protecting company resources that were not previously identified in the West. Antecedents of OCBs also vary across cultures. Meyer et al. (2002) found that normative commitment was more strongly associated with OCBs in non-Western contexts, whereas affective commitment is particularly important for OCBs in the United States. Organizational-based self-esteem has been found to mediate the effect of collectivism on OCBs (Van Dyne et al. 2000). Studies have shown that commitment to one’s supervisor is a more powerful predictor of OCBs than are organizational attitudes in the Chinese context (Cheng et al. 2003). Research has also found that fulfilment of psychological contracts predicts OCBs in non-Western cultures such as China (Hui, Lee & Rousseau 2004) and Hong Kong (Kickul, Lester & Belgio 2004).

In India, the absence of commercial ground rules comparable to the U.S. economy means that the organization is vulnerable to capricious enforcement of legal and regulatory codes (Ahlstrom et al. 2000). The lack of a well-developed and tractable due process system means that in order to protect itself from such capricious threats to its effectiveness, an organization must develop external support for its practices and institutional presence. This involves not only good personal relationships between its top managers and local government leaders, but also a generalized sense in the community that it is a positive contributor to the welfare of the locality. This can be done by involvement of the organizations’ employees in both formal and informal activities benefiting the community. Therefore, we anticipate that an important component of OCB in India would involve discretionary prosocial gestures by internal staff in the surrounding community.

Contextual factors, such as organizational culture and job characteristics also impact decisions to engage in OCBs (Fodchuk, 2007). It also appears that individuals in development focused organizations might react more favourably to using OCBs than individuals in results-focused organizations. Similarly, the national culture in which an organization is embedded (collectivistic versus individualistic) could impact reactions (Gelfand, Erez & Aycan, 2007).

into bitter conflict at a major level between in-groups and out-groups, affecting not only organizational affairs, but also spilling over into the community. Escalation of conflict presents serious risks. Thus, in India the initiative taken to change the status quo is less likely to be considered as OCB.

Another implication of cultural collectivism has to do with the more personal forms of OCB. In North America, the OCB ‘altruism’ or ‘helping’ is defined as assistance given to co-workers for job related matters—i.e., the help is given to the co-worker because the co-worker is just that, a colleague defined by work roles. In India, the co-worker is also considered a friend, neighbour, comrade, and fellow community member and, thus, OCB might well include assistance on a purely personal level, e.g., helping co-workers with family problems or dwelling repairs, or ministering to them when they are ill.

Markoczy (2004) argued for the need to distinguish active positive contributions from avoiding doing harm to others within the concept of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). The usefulness of this distinction is demonstrated by showing that avoidance of harmful behaviors plays a major role in national differences in what is considered to be OCB.

Need for a culturally specific measure

Farh, Earley and Lin (1997) developed an OCB scale for China. However, replication of such attempts for different cultures/nationalities is needed. Farh et al. (1997) claimed that there are etic (universal) and emic (culture specific) dimensions of OCB. Lam et al. (1999) found support for etic/emic distinctions; they report that U.S. and Australian did not differ from their counterparts in Japan and Hong Kong while rating if etic OCB items formed their expected role requirements. Paine and Organ (2000) also suggest that different cultures/nations may interpret or evaluate the OCB differently. They identify individualism-collectivism and power distance as potential sources of variations in the research findings obtained in US context. Farh et al. also found that two dimensions of OCB, courtesy and sportsmanship, did not match with any of the five dimensions of the Chinese OCB developed by them. Studies also indicate that some measures of OCB developed in North America behave differently in other countries. In a cross-cultural study, Kwantes (2003, p. 16) reports that published factor loading pattern (for 19 item OCB scale developed by Moorman & Blakely, 1995) and obtained loading pattern got significantly correlated for US sample (r = 0.55, p< 0.05), but not in the case of Indian sample (r= 0.34, p> 0.05).

Only two studies (Chaitanya & Tripathi, 2001; Kumar, 2005) have attempted to develop a scale for Indian context. Besides the five OCB dimensions suggested by Organ (1988), Chaitanya and Tripathi (2002, p. 221) suggested an additional dimension ‘display of voluntary behavior’ distinct from ‘altruism’ dimension of Organ. They argued that all altruistic behaviors are voluntary, but the converse is not true. The above considerations strongly suggest that a new OCB measure should be developed for Indian context.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

According to Schwab (1980) there are four stages in the process of scale development.

a) Defining the theoretical construct to be measured

c) Scale development: In this step the response format of the items, as well as the manner in which the items are combined to form the scale, is decided. Scale development consists of collecting data with the use of a preliminary form and analysing the data in order to select items for a more final form.

d) Scale evaluation: in this stage the psychometric properties (reliability and validity) of the scale is tested.

Defining OCB

The definition of OCB as proposed by Organ (1988) was used for the present study. He defined OCB as ‘individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization’ (Organ 1988, p. 4).

Item generation

To develop items to measure OCB, several specific examples of such behaviors were generated taking cues from existing scales and literature of OCB and OCP. Skilful interviewing can elicit a wide range of statements about the variable in question (Dawis, 1987). Thus, five managers (commercial banks), four doctors (medical college), two principals (college), nine employees (three from each organization) participated in several group discussions to generate items for the purpose of developing scale for measuring OCB. The items generated by these practitioners were combined with those generated from review of literature and existing scales. While editing the items, the utmost care was taken to avoid double-barrelled questions, non-monotonic questions and question using any vague words or phrases. The combined pool thus generated consisted of 140 items. Out of these 140 items 80 were developed by the practitioners and the remaining 60 were developed from the existing scales and the review of literature.

Assessment of content validity

To asses the content validity of the combined pool of items generated, these items were presented to 10 judges (consisting of supervisors, employees, faculty members and Ph.D. students in advance stages of their research) along with the definition of OCB. These judges were, therefore, requested to rate the items on the following scale depending on the degree to which they believe that the given item belongs to the construct of Organizational Citizenship Behavior:

• Completely disagree (CDA)—If the item does not at all belong to the construct of Organizational Citizenship Behavior.

• Slightly agree (SLA)—If the item seems to belong to the construct of Organizational Citizenship Behavior but the agreement is weak.

• Moderately agree (MA)—If the item seems to belong to the construct of Organizational Citizenship Behavior but the agreement is somewhat stronger.

• Strongly agree (STA)—If you strongly agree that the item belong to the construct of Organizational Citizenship Behavior.

• Totally agree (TA)—If the item totally belongs to the construct of Organizational Citizenship Behavior.

Scale Format

In choosing a scale format, the general rule might be to choose the simpler format. However, there are other considerations: More complex formats might make the task of filling out the scale more interesting for the more experienced or knowledgeable respondent. When rating response formats are used, more scale points are better than fewer, because once the data are in, one can always combine scale points to reduce their number, but one cannot increase that number after the fact (Dawis, 1987). Also, more scale points can generate more variability in response, a desirable scale characteristic if the response is reliable. Considering the above arguments, the response choices of the scale used in this study consisted of five points:

Never (1)

Rarely (2)

Sometimes (3)

Frequently (4)

Always (5)

Scale Development

Scale development consists of collecting data with the use of a preliminary form and analyzing the data in order to select items for a more final form. (‘More final’ is intended to indicate that the process might have to undergo one or more iterations depending on the results of the evaluation stage.) It is always useful to conduct a small N pilot study before the main data collection effort. So the scale was administered to 20 doctors to check out such nuts and-bolts points as how easily the scale instructions are followed, how well the scale format functions, how long the scale takes to complete, and especially, how appropriate the scale items are for the target respondent population. As a rule, the development sample should be representative of the target respondent population. There can be exceptions, however; for example, in developing stimulus-centred scales, one could use a sample that is more homogeneous than samples from the target population. After this first administration of the test, minor modifications were made in the scale. Only five items were reworded to make their meaning more clear.

Participants

To collect the data, we recruited the help of four research scholars to distribute the OCB survey in various organizations. The participants were selected randomly and the final sample consisted of 98 Indian participants in varied job functions from various sectors such as banking, medical, education, telecommunication and other private enterprises. Participants were recruited across organizations, rather than from within one organization, because of evidence demonstrating that OCB can be a group-level phenomenon (Ehrhart, 2004). Therefore, choosing all participants from one organization may have resulted in more similarity in their responses, making the results specific to that organization, rather than generalizable across organizations.

Their mean age was 34.8 years (SD= 5.4). Among them, 68% were male, 45% were in supervisory positions, and 54% had at least an undergraduate education. Thus, our sample was highly diverse, and given the fact that the average number of respondents from each organization was about fifteen, it is unlikely that any particular industry, technology, or job function exerted disproportionate weight on the responses of the items generated to measure OCB.

pattern, and the survey was based on self report, checking for socially desirable response pattern became necessary. In addition to assessment of demographic variables, Short Social Desirability Scale developed by Crowne and Marlowe was administered with the 43 items Organizational Citizenship Behavior Inventory (OCBI).

Correlation with Social Desirability Scale

If there is a significant correlation between the responses to a particular item and the respondents’ total score on social desirability, it indicates the presence of a socially desirable response pattern for that particular item. 7 items (out of 43) correlated significantly with the total score of short social desirability scale and these 7 items were excluded from further analysis. Thus 36 items were retained for further examination of item-total correlation.

Item-total correlation

It is a broader question since it is based on how one item relates to other items that are expected to be measuring a common construct by finding the correlation of an item to a score (sum) of the other items. Low correlations mean the item is not a coherent part of a set of similar questions. Selection of closely knit or highly correlated items with the total score ensures better reliability for the proposed scale. The item-total correlation found using SPSS 12 showed that three items do not correlate significantly with the total score, thus these three items were excluded—thus leaving a total of 33 items for further evaluation.

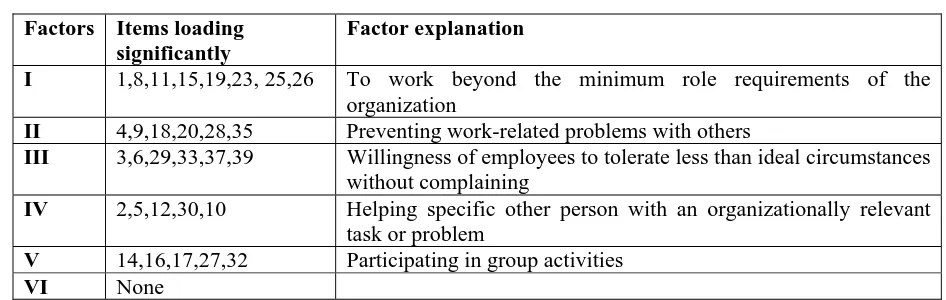

Exploratory factor analysis

To explore the latent dimensions underlying the remaining 33 items these items were factor analyzed using principal component method. Since the initial factor structure was not clean, the factors were rotated using orthogonal rotation (Varimax). Six factors having Eigen value of more than 1 emerged explaining 58.04 of the total variance. The rotated factor matrix is shown in the table 2 above.

TABLE 2: Rotated Component Matrix

Items I II III IV V VI Communality(h2)

Items I II III IV V VI Communality(h2) OCB 19 0.871 0.163 0.003 0.232 0.219 0.29 0.971104 OCB 20 -0.006 0.744 0.082 -0.026 0.272 0.048 0.63726 OCB 23 0.81 0.189 0.101 0.117 0.198 -0.019 0.755276 OCB 25 0.742 0.264 0.076 0.212 -0.203 0.014 0.712385 OCB 26 0.593 0.036 0.23 0.351 0.258 0.021 0.596051 OCB 27 0.016 0.177 -0.16 0.241 -0.68 0.089 0.585587 OCB 28 0.153 0.657 -0.04 -0.157 0.228 -0.248 0.594795 OCB 29 0.104 0.112 -0.532 0.141 0.205 -0.129 0.384931 OCB 30 0.162 0.165 0.251 0.416 0.023 0.317 0.390544 OCB 31 0.292 0.138 0.082 0.283 -0.109 0.223 0.252731 OCB 32 -0.135 0.189 -0.001 0.289 -0.84 -0.211 0.887589 OCB 33 0.143 0.063 -0.752 0.178 -0.296 0.265 0.779447 OCB 35 0.043 0.856 -0.04 -0.262 -0.226 0.099 0.865706 OCB 37 -0.103 0.174 -0.758 0.107 -0.003 0.072 0.632091 OCB 38 0.105 0.117 0.119 0.029 0.039 0.036 0.042533 OCB 39 0.066 0.241 -0.646 0.125 0.049 0.054 0.699439 OCB 43 0.126 0.124 0.126 0.154 0.244 0.206 0.172816 Variance

(%) 12.40 11.84 10.78 10.31 9.58 3.14 58.04

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

TABLE 3: Items loading significantly on their respective factors

Factors Items loading significantly

Factor explanation

I 1,8,11,15,19,23, 25,26 To work beyond the minimum role requirements of the organization

II 4,9,18,20,28,35 Preventing work-related problems with others

III 3,6,29,33,37,39 Willingness of employees to tolerate less than ideal circumstances without complaining

IV 2,5,12,30,10 Helping specific other person with an organizationally relevant task or problem

V 14,16,17,27,32 Participating in group activities

VI None

Using an inductive approach to explore the content domain of OCB in India, we identified five major OCB dimensions—conscientiousness, helping co-workers, group activity participation, sportsmanship and courtesy which are similar to those that have been empirically investigated in the Western OCB literature. This suggests that these five dimensions have broad applicability across cultures. However, the specific behaviors that constitute the construct domain of these dimensions are far from identical. For example, helping co-workers in India includes non-work helping, which is typically not considered part of altruism in the United States.

Reliability analysis

The reliability of the whole scale was found out to be 0.82. Table 4 provides the reliability (Chronbach alpha) of the various subscales developed.

TABLE 4: Reliability of various subscales

Subscale Label Reliability

F1 Conscientiousness 0.71

F2 courtesy 0.75

F3 Sportsmanship 0.81

F4 Helping co-worker 0.91

F5 Group activity participation 0.79

Limitations and implications

A number of limitations to this study can be identified. First the issue of common method variance needs to be considered given the cross-sectional design of the study based on self report. Meta-analytic studies of these constructs (Meyer et al. 2002; Organ & Ryan 1995) suggest that studies relying only on self-report may either inflate correlations or, in a cross-sectional design, might introduce problems of instability in correlations due to situational moderators. For the assessment of OCB future research should aim at gaining independent assessments (Bentein et al. 2002; Chen & Francesco 2003) such as the use of either supervisor rating or direct observation of OCB. Supervisor ratings may similarly suffer from the problem of a cultural tendency not to criticize, however direct observation would require awareness of group norms of behavior.

may seem at first sight. Vandenberghe (2003) neatly outlines the difficulties between, on the one hand, designing appropriately ‘emic’ scales that tap into local construction of the self, and on the other using ‘etic’ scales that facilitate direct comparison between different groups. Wasti (1998, 2003) took the route of developing integrated emic-etic measures, which limit cross-cultural comparison, while the majority of other authors focus on translating original scales, which may not capture local meaning. This study combines the two approaches; most of the data are derived from direct translations of original scales, but the construction of OCB in India was addressed through the initial interviews and amendments made in direct response to local mores. That the study demonstrates considerable similarities in the structures of OCB, and their relationships with North American data, but with differences that are understandable within the local context, suggests that the prevailing models describe generic constructs that can be specifically interpreted. Thus, our findings are exploratory in nature and need to be confirmed in future research before broad generalizations can be made.

To summarize, the factor structure of OCB obtained in the analysis is appealing. First, the study demonstrates that the concepts of organizational citizenship behavior translate to the Indian context, with suitable (and predictable) amendments. Second, the correlated structure of the components of OCB is confirmed. The findings imply that the concept of OCB is applicable for the study of individual’s behaviors in a very different cultural context using a large sample across a variety of industries.

REFERENCES

Ahlstrom, D, Bruton, GD & Lui, SY 2000, ‘Navigating China’s changing economy: Strategies for private firms.’ Business Horizons, 43, 5–15.

Brief, AP & Motowidlo, SJ 1986, ‘Prosocial organizational behaviors.’ Academy of

Management Review, 11, 710–725.

Chaitanya, SK and Tripathi, N 2001, ‘Dimensions of Organizational Citizenship Behavior.’

Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 37, 217-230.

Chang, J 1991, Wild swans, Simon and Schuster, New York.

Cheng, B, Jiang, D & Riley, JH 2003, ‘Organizational commitment, supervisory commitment, and employee outcomes in the Chinese context: proximal hypothesis or global hypothesis?’

Journal of Organization Behavior, 24, 313–34.

Child, J 1994, Management in China during the Age of Reform. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

Coyle-Shapiro, JAM, Kessler, I & Purcell, J 2004, ‘Exploring organizationally directed citizenship behavior: Reciprocity or ‘It’s my job’?’ Journal of Management Studies, 41, 85–106.

Crowne, DP & Marlowe, D 1964, The approval motive. Wiley, N.Y.

Dawis, R 2000, Scale construction and psychometric considerations in H. EA Tinsley & SD Brown (eds.), Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling, Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 65–94.

Ehrhart, MG 2004, ‘Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unit-level organizational citizenship behavior.’ Personnel Psychology, 57, 61–94.

Farh JL, Earley, C & Lin, S 1997, ‘Impetus for action: a cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese society’, Administrative Sciences Quarterly, 42, 421–44

Farh, J, Tsui, AS, Xin, K & Cheng, BS 1998, ‘The influence of relational demography and

guanxi: The Chinese case’, Organizational Sciences, 9, 471–488.

Fodchuk, KM 2007, ‘Work environments that negate counterproductive behaviors and foster organizational citizenship: Research based recommendations for managers’, The

Psychologist—Manager Journal, 10, 27–46.

Gelfand, MJ, Erez, M, & Aycan, Z 2007, ‘Cross-cultural organizational behavior’, Annual

Review of Psychology, 58, 479–514.

George, JM & Brief, AP 1992, ‘Feeling good, doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship’, Psychological Bulletin, 112, 310–329. Graham, JW 1991, ‘An essay on organizational citizenship behavior’, Employee

Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 4, 249–270.

Hui, C, Lee, C & Rousseau, DM 2004, ‘Psychological contract and organizational citizenship behavior in China: investigating generalizability and instrumentality’, Journal of Applied

Psychology, 89, 311– 21 .

Katz, D 1964, ‘The motivational basis of organizational behavior', Behavioral Sciences, 9, 131–146.

Kickul, J, Lester, SW & Belgio, E 2004, ‘Attitudinal and behavioral outcomes of psychological contract breach: a cross cultural comparison of the United States and Hong Kong Chinese’, International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 4,.229–49.

Kumar, K, Bakhshi, A & Rani, E 2009, ‘Linking the ‘Big Five’ personality domains to Organizational citizenship behavior’, International journal of Psychological studies, 1, p. 2.

Kumar. R 2005, Organizational citizenship performance in non-governmental organizations:

Development of a scale: IIM, Ahmedabad.

Kwantes, CT 2003, ‘Organizational citizenship and withdrawal behavior in the USA and India: Does commitment make a difference?’ International Journal of Cross Cultural

Management, 3, 5-26.

Lam, SK, Hui, C & Law, KS 1999, ‘Organizational citizenship behavior: comparing perspectives of supervisors and subordinates across four international samples’, Journal of

Applied Psychology, 84, 594– 601.

Liden, RC, & Maslyn, JM 1998, ‘Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development, Journal of Management, 24(1), 43–73. Meyer JP, Stanley, DJ, Herscovitch, L & Topolnytsky, L 2002, ‘Affective, continuance, and

normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52.

Moorman, RH & Blakely GL 1995, ‘Individualism-collectivism as an individual difference predictor of organizational citizenship behavior’, Journal of Organization Behavior, 16, 127–143.

Morrison, EW 1994, ‘Role definitions and organizational citizenship behavior: The importance of the employees’ perspective’, Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1543– 1567.

Motowidlo, SJ, Borman,WC & Schmit, MJ 1997, ‘A theory of individual difference in task and contextual performance.’ Human Performance, 10, 71–83.

Nunnally, JC 1967, Psychometric theory. McGraw Hill: NY.

Organ, DW & Ryan, K 1995, ‘A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior’, Personnel Psychology, 48,.775–802. Organ, DW 1988, Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome.

Organ, DW 1997, ‘Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time’, Human

Performance, 10, 85–97.

Paine, JB and Organ, DW 2000, ‘The cultural matrix of organizational citizenship behavior: Some preliminary conceptual and empirical observations’, Human Resource Management

Review, 10, 45-59.

Podsakoff, PM, MacKenzie, SB, Paine, JB. & Bachrach DG 2000, ‘Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research’ Journal of Management, 26, 513–563.

Schwab, DP 1980, ‘Construct validity in organization behavior’, in BM Staw and LL Cummings (eds.), Research in Organization Behavior, CT: JAI Press, Greenwich, pp. 3-34. Smith, CA, Organ, DW & Near, JP 1983, ‘Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and

antecedents’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 653–663.

Van DL, Cummings, L. & McLean, JM 1995, ‘Extrarole behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (A bridge over muddied waters)’, Research in Organization

Behavior, 17, 215–285.

Van DL, Graham, JW & Dienesch, RM 1994, ‘Organizational citizenship behavior: Construct redefinition, measurement, and validation’, Academy of Management Journal, 37, 765-802. Van Dyne, L, Vandewalle, D, Kostova, T, Latham ME & Cummings LL 2000, ‘Collectivism,

propensity to trust and self esteem as predictors of organizational citizenship in a non-work setting’, Journal of Organization Behavior, 21, 3–23.

Van Dyne, L & LePine, JA. 1998, ‘Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity’, Academy of Management Journal, 41, 108–119.

Vandenberghe, C 2003,’ Application of the three-component model to China: Issues and perspectives’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 516-523.

Wasti, SA 1998, ‘Cultural barriers in the transferability of Japanese and American human resources practices to developing countries. The Turkish case’, International Journal of