Volume 9 Number 2 2012 www.wwwords.co.uk/ELEA

Project-Based Learning in a Technologically

Enhanced Learning Environment for

Second Language Learners: students’ perceptions

LINDSAY MILLER, CHRISTOPH A. HAFNER & CONNIE NG KWAI FUN

City University of Hong Kong

ABSTRACT This article presents a new approach to English for Academic Purposes (EAP) course design. Situated in the context of an English-medium university in Hong Kong, the article describes an undergraduate course in English for science, which focused not only on traditional academic genres but also engaged students in the creation of a multimodal scientific documentary via a digital video project. As part of this project, students carried out a simple scientific experiment, documenting procedures, results and interpretation in the form of a digital video uploaded and shared through YouTube. This method of presenting scientific information not only engaged students in novel, multimodal forms of representation, but also involved them in an online learning community consisting of their tutor, classmates, other peers as well a wider Internet audience. This use of multimodal scientific documentaries as a pedagogical tool in EAP is reported with reference to data drawn from a student questionnaire, interviews with students, and students’ comments in a course weblog. The findings show that the students perceived both linguistic and technical value in the construction and sharing of their multimodal documentaries.

Introduction

One challenge in designing an English for Academic Purposes (EAP) course for twenty-first century language learners is to ensure that learners improve their academic language skills, while also catering to their increasing technological sophistication. Students born after 1980, who have grown up immersed in digital technologies, are referred to as the ‘net generation’ (Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005) or ‘digital natives’ (Prensky, 2001). Such students differ in fundamental ways in how they approach the use of technology for communication and learning. They do not see technology as an ‘add on’; as Conole (2008, p. 138) maintains, ‘it is central to how they organize and orientate their learning’. Therefore, the implication for university tutors is that they have to ‘radically rethink how courses are designed’ (Conole, 2008, p. 138). A twenty-first century student is also no longer just a passive consumer of media; many are now also becoming competent in producing and sharing their own creative work in online ‘affinity spaces’ (Gee, 2004) like Flickr (photo sharing), YouTube (video sharing) or FanFiction.net (fan fiction writing). These spaces can act as informal learning communities, bringing together diverse groups of people who support one another in the pursuit of common shared interests that they are passionate about. As a result, the learning experiences for this type of student are very different from those of previous generations. These students expect their EAP tutors to use new technologies in the management, delivery and assessment of their courses – a challenge met with differing degrees of success.

their background, prior IT expertise, learning preferences or subject discipline studied’ (p. 126). Citing two case studies of non-native English students (from Turkey and China), Conole drew up a long list of technology tools these students used in their everyday lives both in and out of class: email, mobile phones, PowerPoint, search engines, Teacher TV, library system, voice recorder, etc. Various other surveys show that the penetration level of technology in young peoples’ lives in developed countries is very high: Internet use in the USA of teens aged from 14-17 is 95% (Jones & Fox, 2009); while in a survey of students aged 15-24 in Hong Kong it was found that 98% used the Internet for information search and 96% used it for homework tasks (Chan & Fang, 2007). Internet use in the rest of Asia is also on the increase: in Thailand the penetration rate has jumped from 3.7% in 2000 to 26.3% in 2010, while in China the rate increased from 1.7% in 2000 to 36.3% in 2011 (Internet World Stats, 2011).

The degree of student use of new technologies varies widely. However, according to a 2005 study in the USA (Lenhardt & Madden, 2005), more than half of all teens who used the Internet could be considered to be ‘media creators’. A media creator ‘is someone who created a blog or webpage, posted original artwork, photography, stories or videos online or remixed online content into their own new creations’ (Jenkins et al, 2006, p. 6). Several case studies demonstrate how English language learners have extended their linguistic skills by participating in online affinity spaces as media creators. Lam (2000) describes the case of Almon, a Hong Kong Chinese teenager who set up a J-pop website and began to communicate with a number of ‘pen pals’ worldwide. As a result of his website Almon overcame his awkwardness in learning English and boosted his confidence in using the language in other social and learning contexts. Black (2006) reports on another Chinese Internet user who at 14 years of age, and after only two and a half years of learning English, began posting anime-based stories on Fanfiction.net. ‘Nanako’ became something of a celebrity for her stories and although she sometimes referred to her ‘poor English’ this did not prevent her from engaging in media creation and interacting with online admirers of her fan fiction writing. In fact, participating in this online affinity space provided her with opportunities to learn English through the feedback she received on her writing, and also allowed her to develop a robust multicultural identity as a writer of English.

From our own experiences as university tutors we find that our students have access to a technology-rich learning environment. Our students communicate with us, their tutors, and their classmates via the intranet and Internet; they use the university’s web-based learning management system (Blackboard) to access information about their courses and find out what is happening in the university; they find learning materials online; and they prepare presentations and submit assignments with the use of new technologies. In their 2008 study, Conole et al (2008) concluded that

One of the most striking features to emerge from the data is the extent to which students are capitalizing on the social affordances of technologies ... in terms of peer support and

communication – the picture emerges of a networked, extended community of learners using a range of communicative tools to exchange ideas, to query issues, to provide support, to check progress. (p. 521)

Thus, students use new technologies to gain access to online learning communities, in which participants provide their peers with guidance and support in pursuit of their mutually shared interests.

Given the pervasiveness of new technologies in our students’ lives, we have to take heed of the calls of other researchers and find space in our course designs to use new technologies to aid our students’ learning (Warschauer, 2000). One way to go about this in EAP course design is to adopt a project-based learning (PBL) approach, with students’ language learning driven by the need to complete a meaningful project of some kind. Such an approach lends itself to the use of new technologies because students can be encouraged to draw on a range of technological tools in order to research, present and share their projects. For example, students can present their projects by creating innovative digital texts, like the digital videos described in this article, and these texts can in turn be shared within a peer-supported online learning community as well as a wider online audience.

language skills: listening (Gardner, 1995); reading (Bosuwon & Woodrow, 2009); speaking (Mennim, 2003); and writing (Yeh, 2009). PBL is useful for language learners for a variety of reasons, some of which are:

• It integrates the use of the four language skills;

• Learners can use a variety of skills other than language skills to communicate (drawings, models, photographs etc.);

• It allows learners who are strong in one area (language, technical, management) but weak in others to contribute to a project;

• It encourages cooperation between learners;

• Learners become more autonomous of their teachers and take responsibility for their own learning;

• It creates real-life links with learners’ experiences inside and outside of the classroom.

PBL has been used in many learning contexts over the past twenty or so years: business, law, and architecture (Savey & Duffy, 1995), medicine (Barrows, 1996), management (Ayas, & Zenuik 2001), and engineering (Mills & Treagust, 2003). One of the main reasons for using PBL is to take the focus off surface-based learning (i.e. rote learning to pass a test) and place it on mastery-based learning (i.e. deep learning in order to understand a topic or issue more). Thomas (2000) outlines a list of five criteria in determining if language learning work can be considered as PBL. These criteria may act as a definition of sorts. They are:

1. PBL projects are central, not peripheral to the curriculum;

2. PBL projects are focused on questions or problems that ‘drive’ students to encounter (and struggle with) the central concepts and principles of a discipline;

3. Projects involve students in a constructive investigation; 4. Projects are student-driven to some significant degree; 5. Projects are realistic, not school-like.

The digital video project described in this article illustrates the integration of PBL with new technologies in an attempt to cater to the increasing technical sophistication of our students. After outlining the project we present the students’ perceptions of their experience of this ‘new’ form of language learning.

Background

The course discussed in this article is an existing university English course offered to science students at an English-medium university in Hong Kong. The course is a core course and the credits gained form part of the students’ overall Grade Point Average (GPA) at the end of their degree programme. As such, the course has high stakes for the students. The course aims to ‘develop students’ ability to read a variety of scientific texts, and appropriately communicate (through speaking and writing) the findings of scientific projects in an academic context’ (course documentation). It is a 39-hour course offered in teaching blocks of three hours per week over a thirteen-week semester. The students taking this course all belong to the biology, chemistry, and mathematics departments and are around twenty years old. The majority of students are Hong Kong Chinese with Cantonese as their first language. Others are from Mainland China and have Mandarin as their first language. Three experienced tutors in the English department (who also formed the research team) are responsible for teaching the course.

Course Development

In restructuring an existing EAP course for science and mathematics students we introduced a digital video project to replace the existing oral presentation. There were a number of reasons why we wanted the students to take part in a digital video project:

1. We wanted the second language students to move away from the read-out-loud syndrome they had become used to when giving presentations in class.

2. We wanted to give students an opportunity to experience the digital video medium, incorporating new technologies and new forms of multimodal representation into their learning.

3. We wanted to capitalize on the students’ existing technological expertise.

4. We wanted students to use the video feedback in order to notice, and then correct, shortcomings in their presentation skills (concerning both language and content).

In order to involve students in the kinds of multimodal participatory media practices that they engage in in their everyday lives, we asked our students to prepare a 10-minute scientific documentary in the form of a digital video which would be uploaded to YouTube and shared through a publically accessible course weblog (see below). Students were encouraged to make the presentation of their documentaries as creative and entertaining as possible.

As we had students from a range of disciplinary backgrounds, we opted for topics which required no in-depth specialist subject knowledge and which would be accessible to the students as well as to the English tutors teaching the course. We offered a choice of two different topics: a study of the blind spot in the human eye; a study of the senses of smell and taste in humans. The two topics were generic enough for the English tutors to support, but also had strong scientific underpinnings, requiring students to do background research, formulate hypotheses, collect and interpret data. When they were complete, all videos were viewed in a class sharing session and oral feedback was given by both classmates and tutors. An example of the introductory worksheet given to students to guide them in their project can be seen in the Appendix. More information about the course including materials, rubrics used and a detailed evaluation of the new EAP course design can be found at the project website (http://www1.english.cityu.edu.hk/acadlit).

Structure of the Technological Learning Environment

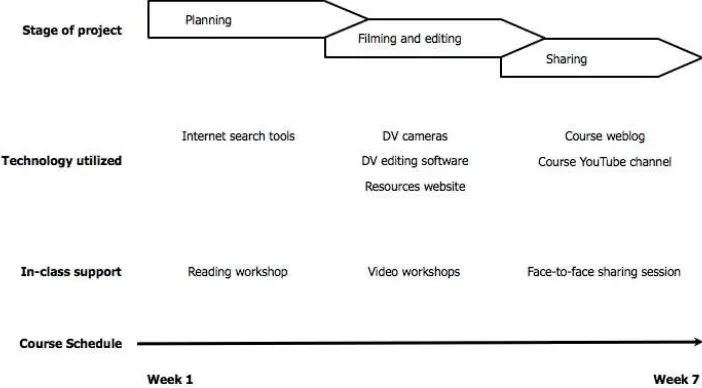

In order to support student learning, we created a ‘technological learning environment’, with a full range of technological tools and resources to help students plan, construct and share their digital scientific documentaries. The design of this technological learning environment was based on a modular system, with a number of loosely connected technological platforms and devices used to support student learning. Students and tutors used the university’s online learning management system for course administration, a course weblog for reflective discussions on coursework and learning, digital video cameras and editing software for video production, an online resource website for video editing support (in the form of ‘how-to’ screencasts), and the YouTube platform for video sharing (videos were also embedded in the course weblog). Figure 1 shows the structure of the technological learning environment and how the technology supported different stages of the digital video project.

Stage 1: Planning

(a) As an in-class activity we introduced students to an example of a scientific documentary. Students watched a short BBC documentary about the benefits of drinking water (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fK2b6UtVW70), and then discussed how the information had been presented. We wanted to sensitize our students to the way science can be presented in a less formal or academic way (this was later contrasted in the course with the lab reports students wrote, and so they became more aware of issues of genre, audience and purpose in their writing). Areas covered included:

(iii)What was the mixture of pictures, text, narration, video? (iv)What type of language was used in the video?

(v) What specific vocabulary was introduced in the video? Was it technical vocabulary? If so, how was it exemplified?

(b) We held a classroom discussion based on the video in (a), pointing out to students that the scientific documentary viewed both conformed to scientific conventions for structure (introduction, methods, results, and discussion) and at the same time contained elements of narrative, interviews, visuals and interesting facts in order to maintain audience interest.

(c) We introduced students to Photostory 3 for Windows which they could use when making their videos (see Stage 2(c) for more technology tools which were introduced). This freely downloadable software allows the user to create a ‘digital story’ from images, with an audio narration.

(d) Important aspects of running the project included project management and teamwork. We had group discussions about who would be responsible for which aspect of the project. Some of the different possible roles we discussed with students were:

(i) Researcher: co-ordinates the necessary background research, and helps interpret findings (ii) Fieldworker: co-ordinates the collection of data, enlisting participants

(iii)Director: co-ordinates the script and storyboard for the video

(iv)Camera operator: co-ordinates the filming and photographs, and the necessary equipment (v) Editor: co-ordinates the final editing and production of the video

Students were asked to discuss what roles they would be best at, and then form a team which included people with diverse interests and skills, able to support one another in different aspects of the complex video production task. It was stressed that they should work as a team throughout the project.

Figure 1. Structure of the technological learning environment (from Hafner & Miller, 2011).

Stage 2: Filming and Editing

(a) The students were given the following prompt to guide them in preparing their video documentaries:

Working in groups of 3, create a documentary of your English for Science Project, which documents the process and findings of your experiment. You should include:

– Details of the procedure used – Explanation of your results – A discussion of your results – A brief conclusion

– Any other relevant material needed to better understand your experiment and results.

Your documentary must include a range of media (e.g. video, audio, images, text, diagrams), and all members of the project team must be involved in the narration of the documentary. Extra credit will be given for creative presentation of the information (e.g. use of interesting locations, interesting presentation techniques).

(b) As part of this project we made available to the students hand-held video cameras with microphones. Students could borrow the cameras from us for a day at a time.

(c) In-class activities consisted of having students write a storyboard to guide them when filming their projects. We also introduced support for additional video-editing tools (Windows MovieMaker and iMovie), for students to use in their project. In their project groups students wrote up their storyboards and explored the technical tools in class using their laptop computers. (d) Students then worked out of class to conduct their experiments and record the results on video.

Stage 3: Sharing

In the last stage of the project, students were required to upload their digital video documentaries onto YouTube and these were embedded in posts to the course weblog. This made the projects available to a wide Internet audience.

In week seven, all videos were viewed by the class and peer feedback was given. The students were asked to give feedback on: ‘Organization & Content’; ‘Multimedia & Visual Effects’, and ‘Language’.

Students’ Perceptions

In this section we present a summary of our students’ responses to participation in the digital video project. We use selected comments from the students as representative examples of the general findings for each section, and use pseudonyms, following standard reporting practice in qualitative inquiry. In the evaluation of the project we wanted to investigate the following three questions: 1. What is the potential of the digital video task to meet the disciplinary language learning needs

of our students?

2. What problems did the students encounter while completing the digital video project? 3. How could the digital video task be improved in future?

In general, students enjoyed presenting the findings of their English for science projects through the digital video medium. They found preparing their digital video scientific documentaries to be ‘exciting’ and ‘different’ compared to the ways in which they usually presented projects. Filming themselves and sharing their coursework presentations in this way was a novel process which provided students with plentiful opportunities to review their work and reflect on strengths and weaknesses in terms of their language and presentation skills:

Yeah, I also enjoyed because this is a new kind of learning. So we never met such challenging in high school, so maybe it was a new approach for us to learn how to apply our knowledge in this – making a video in this aspect was very special and this is a new challenge and I think it’s interesting, yeah. (Focus Group: Dan)

Question 1. What is the Potential of the Digital Video Task to Meet the Disciplinary Language Learning Needs of our Students?

academy and workplace. The main idea is to provide students with opportunities to develop the necessary literacies for the specific English language tasks that they encounter in the disciplinary domain (e.g. reading and writing in the discipline). In this regard, the questionnaire results and focus group interviews highlighted three areas of interest: 1. Authenticity; 2. Language skills; 3. Teamwork, collaboration and community.

Authenticity. The task of orally presenting a project is something students have to do in a number of their university courses. As such, they were familiar with the concept of being assessed in this way. What made their presentation on this course different was the fact that they were required to present in the form of a scientific documentary through the digital video medium. Students thought this novel and suggested that it was a more interesting way to present their work. Sharing the documentaries publically through YouTube also alerted the students to the possibility that a ‘real’ audience might view their work. Many students felt motivated to engage with this Internet audience and put a great deal of effort into polishing their work as a result. In addition, a number of students reported sharing their videos with their own social networks through websites like Facebook.

It was fascinating when we record the video together during an English project. Different to a normal presentation, sometimes it’s too boring if it’s just a presentation, so videos are quite fascinating. (Questionnaire: ID20)

I think our audience is my classmate as well as the public. Um, my classmate because we – we have to show the video during the class, so our classmates definitely our audience. And because we upload the video on YouTube and everyone can search for our video so that public is also our audience. (Focus Group: Angel)

Students were generally positive about the digital video task, and commented that the ability to present their work through the digital video medium was a useful skill for students in the twenty-first century. On the other hand, students tended not to be able to see any direct link between the digital video project and disciplinary tasks or future workplace needs. This is perhaps not surprising, considering that the topics used were rather broad and not aimed at any particular discipline, and the students had little or no work experience. In spite of this limitation, a few students pointed out that the skills they were practising were transferrable to their disciplinary courses. First, they commented that the project provided them with the opportunity to experience a process of scientific investigation. Second, they noted that the task gave them the opportunity to consider how to incorporate elements of multimedia in presentations, and said that they would pay greater attention to this aspect in future.

There are many elective courses and for small tutorial class students are required to present more frequently and so this is useful for study and especially in electives. (Focus Group: Yau)

Language skills. From the questionnaire data many of the students indicated that they felt they had improved their general English language skills by completing the project: oral skills, including presentation skills (73%) and pronunciation (67%), were ranked as being areas that students felt that they had improved on most. Students commented that, in the process of recording the video, they frequently reviewed their performances and re-recorded sections of their videos many times in order to get as good a production as they could:

By doing research and expressing your idea in English, it also trains your English skills. So, I mean in a sense, it is an integrated work. (Focus Group: Xen)

And pronunciation is sure ... we record our script then we can hear our record and know that how our pronunciation is good or bad, yes. (Focus Group: Cath)

made the connection that in taking part in the project they improved their overall communication skills, a finding which is related to the following comments on teamwork, collaboration and community.

So actually, I think this project did not only train my English. It also trains my some other skills such as social interactive skills because I have to interview different people and because they are strangers and I have to sort out a way to communicate with. (Focus Group: Xen)

Teamwork, collaboration and community. Working as a team was often mentioned as the most enjoyable aspect of the project. As the students spent a lot of time outside of class working together on the project, they were able to develop personal relationships over and above those that normally develop during the English class. Students reported that this teamwork translated into peer support on many occasions, with members of the team providing one another with assistance with issues of language and IT use.

It was stressed in class that all students had to take part as presenters in the video production. In addition, at the beginning of the project, students were asked to consider which other role(s) they were most suited to or most interested in: director, scriptwriter, editor, technology expert, actor, researcher, fieldworker. Getting students to volunteer for specific roles as well as identifying team mates with complementary skills and interests in this way may have helped with the team cohesion, and also engaged them all in the task. However, one of the most important aspects for the success of producing the video seemed to be the need for a team leader, and most students commented on the need to have a good team leader who would coordinate the tasks each team member was responsible for.

[So what did you guys like the most about the project?] I think the most important thing we learned is

still the video shooting techniques that’s more useful. And we also learn ... collaborations and teamwork and we break it into parts so everybody could take part – be responsible for one part and we at the end, we compile all the works together. So make sure the process is smooth and everything is going better, going well. (Focus Group: Terry)

A leader should make a decision and give jobs to the other members and so the whole project can run smoothly. (Focus Group: Yau)

PBL often results in small learning communities being formed, and we can see that the teamwork element was strong for our project teams. However, the aspect of community went beyond working with a small group of classmates. As the students interacted with all their classmates via the course blog a wider ‘community of cooperative learners’ (Hodges, 1998) evolved, and once the students posted their projects on YouTube a number of them extended the project community further by sharing the link with their peers, who provided feedback through informal online channels like Facebook.

My friends also see the other students’ video (on YouTube). And to be honest, compare with my video is not good and it’s not very well done. And but my friends give me some feedback, how can I make it more interesting, how the flow can not be that boring. And they give some comments for me. (Focus Group: Cath)

Question 2. What Problems Did the Students Encounter while Completing the Digital Video Project? Although the students’ comments about the digital video project collected in the questionnaire and focus group interviews were mostly positive, they did mention two areas where they had problems: time management and technology.

required students to spend time doing background research, collecting data, writing a script, filming and editing. All these activities required team coordination and time management.

The major problem was the lack of time. It’s difficult for us to take the video as we have different timetables. Also, loads of time was required for video editing as we were not familiar with the softwares at the beginning. (Questionnaire: ID07)

It is quite hard to finish it in such short period of time, I wish I was given more time, then maybe our video project be even better. (Questionnaire: ID15)

Technology. Although students felt that they learnt a lot about using the technology during the video-making process they also said that learning to use the software was an area of difficulty for many of them. To overcome some of their difficulties in using the software and produce a final version of their video, students got help from each other or consulted online user manuals. Several students also mentioned that the shooting part of the production was not free of problems. Trying to find suitable background locations and shoot a video on a crowded and noisy campus were the main issues mentioned by the students as challenges.

Editing the video is the most challenging part in the project. Since all the things which include the scene, the audio and statistics must be synchronised. We’ve spent a lot of time in

synchronization. (Questionnaire: ID02)

Technical problems ... I cannot use Windows Movie Maker well when I am editing the video. It took me nearly 6 to 7 hours to finish a part only within 3 minutes. (Questionnaire: ID45)

Question 3. How Could the Digital Video Task be Improved in Future?

Quality-assurance procedures in universities nowadays often ask staff to gather feedback from their students as a way of improving the courses. We agree with this concept, and it relates closely to ongoing EAP needs analysis and course design. Therefore, as part of the evaluation we asked our students what advice they might give to other students who were about to embark on such a project, and we also asked for their suggestions on how to improve the project in the future.

Advice. The students were not short in offering advice to other students who may do a similar type of digital video project. Their advice included:

1. Watch some documentary videos to get more ideas before you begin; 2. Do not wait till the last minute to edit your work;

3. Try to be as creative as you can; 4. Use the Internet to get help;

5. Take more shots so you have more visuals to work with; 6. Try to use animation to catch the viewers’ attention;

7. Get your team mates’ contact details ASAP, and keep in contact; 8. Communicate with your team mates if you need any help; 9. Divide up the tasks for each team member;

10. Practise with the video camera before you try to use it for your project work.

Suggestions. When we asked the students how the project might be improved, two areas stood out in the data: having greater choice of topics for the video production, and having more technical support.

Uh, for me, I will choose some topic as I’m studying biology. I will choose some topic about some animals. So I may do some research on some habitat of the animals and make a video. (Focus Group: Ian)

As I am a science student, I would like to take video that is not related to science. Instead, maybe something that about art or music, I think this will be much more interesting. (Questionnaire: ID03)

As tutors on the course we felt that we had given the students a lot of in-class and online technical support in order to learn the software needed to complete the project. Nevertheless, a number of students suggested that they would have liked even more IT support. This suggestion was not, though, because they were unable to complete the project, but so that they could make a better video product.

Yes. I think besides providing us a digital video, some technician should teach us about how to use the video better. (Focus Group: Jim)

I suggest the department should provide the computer for the student to edit the video because the computer used for the editing is need to be advanced. (Focus Group: Colin)

Conclusion

Project work within an EAP course is not a new idea. What is new about the project described above is the way that it integrates new media, new technologies and language learning in order to engage our second language students within an online learning community (the course weblog) in new forms of multimodal representation and share their finished works to a wide audience on YouTube. In their own lives, students are increasingly engaged in new literacy practices that draw on new technologies. In view of this we believe that it is now necessary to consider how EAP courses can integrate new technologies and develop peer-supported learning communities within online affinity spaces that better reflect the everyday new literacy practices of our students.

The PBL project reported on here adhered to the five criteria outlined by Thomas (2000): it was a central part of the students’ learning; the projects were problem driven; the students were involved in a constructive investigation; they took responsibility for their learning; and the final product was a realistic digital video documentary for an authentic audience.

Students on our course created multimodal scientific documentaries which they seemed proud of and invested heavily in. They were prepared to share their work not only with their tutor or other classmates, but with a wider online audience. By empowering our students as media creators we faced the challenge of how to cater to our EAP students as members of the ‘net generation’. As the students’ comments indicate, the experience for them was a positive one, and one which engaged them in their learning on a variety of levels – both technically and linguistically. Our students not only produced completed digital videos for assessment but, on the way, participated in a wider community of language learners and technology users (classmates and friends whom they engaged with online out of class time about their project) and discovered ways to enhance their own language and technical skills. As digital media becomes increasingly pervasive in our lives, it is important that we, as educators, face the challenge of making our university courses more meaningful to the lives of our students – the digital video project described here is one attempt to do this.

References

Ayas, K. & Zeniuk, N. (2001) Project-Based Learning: building communities of management learning,

Management Learning, 32(1), 61-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1350507601321005

Barrows, H.S. (1996) Problem Based Learning in Medicine and Beyond: a brief overview, in New Directions for

Teaching and Learning. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tl.37219966804/pdf

Beckett, G.H. & Miller, P.C. (2006) Project-Based Second and Foreign Language Education: past, present and future.

Black, R.W. (2006) Language, Culture, and Identity in Online Fanfiction, E-Learning and Digital Media, 32(2), 170-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.2304/elea.2006.3.2.170

Bosuwon, T. & Woodrow, L. (2009) Developing a Problem-Based Course Based on Needs Analysis to Enhance English Reading Ability of Thai Undergraduate Students, RELC Journal, 40(1), 42-64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0033688208101453

Gardner, D. (1995) Student Produced Video Documentary Provides a Real Reason for Using the Target Language, Language Learning Journal, 12, 54-56. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09571739585200451

Gee, J.P. (2004) Situated Language and Learning: a critique of traditional schooling. New York: Routledge. Chan, K. & Fang, W. (2007) Use of the Internet and Traditional Media among Young People, Young

Consumers, 8(4), 244-256.

Conole, G. (2008) Listening to the Learner Voice: the ever changing landscape of technology use for language students, ReCALL, 20(2), 124-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0958344008000220

Conole, G., de Laat, M., Dillion, T. & Darby, J. (2008) ‘Disruptive Technologies’, ‘Pedagogical Innovation’: what’s new? Findings from an In-Depth Study of Students’ Use and Perception of Technology, Computers

& Education, 50, 511-524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2007.09.009

Hafner, C.A. & Miller, L. (2011) Fostering Learner Autonomy in English for Science: a collaborative digital video project in a technological learning environment, Language Learning & Technology, 15(3), 201-223. Hodges, D.C. (1998) Participation as Dis-identification with/in a Community of Practice, Mind, Culture and

Activity, 5(4), 272-290. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca0504_3

Internet World Stats (2011) http://www.Internetworldstats.com

Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Clinton, K., Weigel, M. & Robinson, A.J. (2006) Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: media education for the 21st Century, in Pew Internet & American Life project.

http://newmedialiteracies.org/files/working/NMLWhitePaper.pdf

Jones, S. & Fox, S. (2009) (Eds) Generations Online in 2009, in Pew Internet & American Life project.

http://www.floridatechnet.org/Generations_Online_in_2009.pdf

Lam, W.S.E. (2000) L2 Literacy and the Design of the Self: a case study of a teenager writing on the Internet,

TESOL Quarterly, 34(3), 457-482. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587739

Lenhardt, A. & Madden, M. (2005) Teen Content Creators and Consumers.

http://www.pewInternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Teens_Content_Creation.pdf.pdf

Mennim, P. (2003) Rehearsed Oral L2 Output and Reactive Focus on Form, ELT Journal, 57(2), 130-138.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/57.2.130

Mills, J.E. & Treagust, D.F. (2003) Engineering Education: is problem-based or project-based learning the answer? Australian Journal of Engineering Education.

http://champs.cecs.ucf.edu/Library/Journal_Articles/pdfs/Engineering%20Education.pdf

Oblinger, D. & Oblinger, J.(2005) Is it Age or IT: first steps towards understanding the net generation, in D. Oblinger&J. Oblinger(Eds) Educating the Net Generation, 1-5. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE.

http://www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen

Prensky, M. (2001)Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

Savey, J.R. & Duffy, T.M. (1995) Problem Based Learning: an instructional model and its constructivist framework, Educational Technology, 35(5), 31-38.

Stoller, F.C. (2002) Project Work: a means to promote language and content, in J.C. Richards & W.A. Renandya (Eds) Methodology in Language Teaching: an anthology of current practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.016

Thomas, J.W. (2000) A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning.

http://www.bobpearlman.org/BestPractices/PBL_Research.pdf

Warschauer, M. (2000) The Changing Global Economy and the Future of English Teaching, TESOL

Quarterly, 34(3), 511-535. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587741

APPENDIX

Tutorial 3: Webquest 1 – Sense of sight

INTRODUCTION

One of our most important senses is our sense of sight. But how exactly does our sense of sight work? And how good is our sense of sight anyway? The aim of this webquest is to use the Internet and related resources to obtain the best information possible in order to find out.

TASK

Search the Web and find answers to the following guiding questions related to pulse: • How exactly does our sense of sight work?

• How does our sense of sight compare to that of animals? • What conditions can affect our sense of sight?

• Can you define the ‘blind spot’ in humans? • What causes this blind spot?

• Are men and women equally affected by the blind spot?

Take careful notes on the information that you find, and be prepared to explain the concepts that you discover to other members of the class.

RESOURCES

You may use any or all of the following resources and any other resources that you use to search the Web in order to locate reliable information on this topic. You must evaluate all the information that you find, according to the following criteria:

1. Authorship

a. Who wrote the text? b. How expert are they? 2. Procedures

a. Of research b. Of publication

3. Primary or secondary source? 4. Best available information? Yahoo http://yahoo.com/ Google http://google.com

Google Scholar http://scholar.google.com Wikipedia http://www.wikipedia.org/ Delicious http://delicious.com

en2251 Edublogs links http://en2251.edublogs.org

EXTENSION

Use the information you find from this webquest as a basis for the theory section of your scientific presentation.

CHRISTOPH A. HAFNER is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the City University of Hong Kong. His research interests include academic and professional literacy, educational technology and legal discourse. In addition to his other publications, he has co-authored a book (with Rodney H. Jones) entitled Understanding Digital Literacies: a practical introduction (Routledge, 2012). Correspondence: [email protected]