Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:57

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Student Evaluations of Faculty Grading Methods

Linda E. Holmes & Lois J. Smith

To cite this article: Linda E. Holmes & Lois J. Smith (2003) Student Evaluations of Faculty Grading Methods, Journal of Education for Business, 78:6, 318-323, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309598620

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309598620

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 82

View related articles

Student Evaluations

of Faculty

Grading Methods

LINDA E. HOLMES

LOIS J. SMITH

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

University of Wisconsin-Whitewater

Whitewater, Wisconsin

tudents have the opportunity to

S

rate their instructors at the end of each term through global measures of effectiveness, such as measures ofinstructor knowledge about his

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

or herfield of study, clarity of course objec- tives, and effectiveness of the instruc- tor’s delivery of the material. Included in the typical evaluation are statements or questions concerning grading. Were the grades fair? Were examinations and assignments directly related to reading materials and class lectures? These broad questions give faculty members an idea of student satisfaction with classes, but they generally do not help instructors improve their teaching methods because the ratings are not specific to particular habits or behaviors. Instructors do not know what they do well or poorly according to these measures. In fact, the average teaching evaluation form is not designed to help faculty members improve their teaching or enhance learn-

ing in the classroom (Angel0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Cross,1993). Having limited guidance from students, faculty members use their per- sonal experience and history as students to decide how to handle the grading process (Unwin, 1990).

As we demonstrate through a litera- ture review, most grading-related arti- cles focus on the methods that faculty members should use in the classroom, the areas that should be graded (e.g., content, grammar, organization, arith- metic, process), or methods that seem to

31 8

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Educution for BusinesszyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ABSTRACT. Considerable literatureexists Concerning grading, its purpos-

es, its best practices, and its reliability.

In this research, the authors investigat-

ed students’ complaints about how

faculty members grade them on both essay assignments and quantitative problems. The two major problems cited by students were lack of “fair- ness in grading” and too little feed-

back from their instructors. The

authors explain how strategies such as setting clear assignment objectives and using matrices and, rubrics would

help to reduce these negative student

comments.

lead to better student performance. In these articles, the authors discuss the appropriate use of marginal comments on essays or rubrics for quantitative problems; however, they do not ask stu- dents what they like or dislike about the grading methods used by their teachers. In this study, we sought to investigate university marketing and accounting students’ perceptions regarding the aspects that they found specifically irri- tating with regard to faculty grading of essays and quantitative problems.

In this study, student comments addressed how faculty members graded their papers, not the specific letter or percentage grades assigned. We under- took two student surveys, one asking specifically about essays and another asking about quantitative problems.

Grading: Definition and Issues

The term “grading” has been defined as the process of calculating or measur-

ing a student’s work and assigning a let- ter grade (Speck & Jones, 1998; Tchudi, 1986). Walvoord and Anderson (1998) defined grading as an informed judg- ment made by a professional. Tchudi (1986) suggested that faculty members may also “evaluate” students’ effort by carefully developing assignments, answering students’ questions, com- menting on drafts, and responding to the completed effort. Following this evalua- tion process, the instructor gives a grade. Instructors and students differ in their perceptions of the meaning of grades. Walvoord and Anderson (1998) suggest- ed that grading, from the faculty mem- ber’s perspective, serves multiple educa- tionally important purposes. Grading can evaluate the quality of students’ work as well as motivate students and encourage them to study and become involved in the course. It organizes the course and brings closure to content or

skill areas. How students respond to grades will affect their ability to learn. Attribution theory describes the emo- tional side of grades and two possible groups that students may tend to fall into: Whereas some students feel that they have no control over the outcomes of their work and that nothing they can do will improve poor grades, others feel that they can control their grades and work harder to improve them.

In another categorization approach, students are either grade oriented or learning oriented. Grade-oriented stu-

dents prefer regularly scheduled exams and would be likely to withdraw from courses rather than risk low grades. Alternatively, learning-oriented stu- dents enjoy the process of gaining knowledge and like to discuss concepts outside of class. They are less con- cerned with the grades that they receive than with the knowledge that they gain

(Walvoord

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Anderson, 1998).To further complicate the issue, stu- dents are woefully aware of the subjec- tive nature of the grading process. Stu- dents know that faculty members can make mistakes as they assign grades. The same faculty member may assign different grades to the same paper at dif- ferent times. Research indicates low interfaculty grade consistency on rat- ings of the same paper. These behaviors result in low reliability measures for grading. Grades reflect the biases of individual instructors (Page, 1994). In some cases, the assignment itself may be inappropriate (e.g., it does not follow course objectives). In that situation, even if the instructor grades carefully, the basic assignment is not valid. Grad- ing inconsistency underscores Walvoord and Anderson’s (1998) statement that there is no such thing as “absolutely objective evaluation based on an immutable standard” (p. 11).

Too often, grading does not tell stu- dents what they did well, nor does it allow them to build on their successes. Grades can also promote negative com- petition among students in the class and may lead to cheating (Squires, 1999). Eliminating grading, however, is not a realistic goal for the present. A more immediate strategy is to do the best pos- sible job of maintaining a positive class atmosphere for learning and to see that grades become a tool for motivating stu-

dents and improving their performance.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Grading Practices:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Essays

Researchers agree that some teaching and grading approaches work better than others. Showing students basic respect, listening carefully to them, and assuming that they do want to learn are central to successful classroom experi- ences (Walvoord & Anderson, 1998). Beginning with a list of objectives and then moving to an assignment associat-

ed with those objectives is important. Allowing students time for questions and explaining how grades will be determined are further requirements (Unwin, 1990). In writing assignments, sensitivity to linguistic backgrounds and cultural differences is important. Tchudi stated that the central question for busi- ness faculty members is not “‘Is this good writing?’ (as measured on some absolute scale of literary excellence) but, ‘Does the writing effectively com- municate learning in my discipline?”’ (1986, p. 51). Given the many factors to be considered in grading essays, empha- sis on fairness is as important as giving

feedback.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Fairness

Students should know from the outset that the grading criteria are the same for all students. One way to show students how their grades were calculated is to develop a grading sheet with criteria and weights. Walvoord and Anderson (1998) indicated that this matrix method of grad- ing helps reduce the number of student questions about why they did not receive the grades that they were expecting.

Feedback

Another concern for faculty members is their use of marginal comments and the form that they should take. Speck and Jones (1 998) referred to the use of codes, symbols, and checkmarks within students’ papers as “minimalist grading” that saves faculty members time but may not enhance learning. Putting question marks, exclamation points, or “yes” or “no” in the margins assumes that stu- dents will understand what the teacher is referencing. Faculty members using codes and symbols assume that students actually will look up what the symbols mean and improve their work in follow- ing assignments. These assumptions may be erroneous. Walvoord (1986) suggested that teachers who use codes or symbols should make their associated definitions easily available. The axiom of “less is more” seems appropriate to apply to marginal comments because of the potential for demoralizing or confus- ing students.

Good grading practices would imply

that marginal comments should be accompanied by closing comments that give a summative picture of the stu- dents’ work. The closing comments should address strengths and weakness- es. They give an opportunity to rein- force what students did right as well as to suggest methods to improve. Too often faculty members try to save time by providing only negative communica- tion. Rather than making global pro- nouncements, in these closing com- ments the instructor should ask questions or react to the information as a reader rather than as a professor. Com- ments might ask, “Is this information

supported by research?” or “Didn’t you write this idea earlier in your paper?” Personal comments are appropriate for difficult and sensitive issues. Showing pleasure in the students’ effort is impor- tant to the student-teacher relationship (Tchudi, 1986; Walvoord, 1986).

Other Considerations

The attitude of the instructor when communicating with students does appear to play an important role in how well students respond to the grades that they receive. Giving positive comments along with suggestions for improve- ment, using language that is respectful, and giving evidence of the fairness of the grades are good practices supported by the literature. Although authors dis- agree on how much emphasis should be placed on grammar in grading essays outside of the discipline of English composition, students should be able to communicate clearly to their profes- sional audiences. Because essays and quantitative problems require different grading methods, they also lead to dif- ferent sets of best practices.

Grading Practices: Quantitative Problems

Guidance on grading problems comes from the mathematics education litera- ture. Most of it deals with high school mathematics and focuses on scoring par- tially correct answers and on assessing students’ understanding. However, this literature provides little guidance on assigning points or grades, an issue that is very important at the college level.

July/August 2003 31 9

Answers to written problems have objective and subjective components. The numerical answer, the objective component, is either correct or incor- rect, and an instructor may assign grades based on it, alone. However, an instructor may want to examine the stu- dent’s work further to determine if some parts were correct. This partial credit is the subjective component, which deals with the student’s success in applying relevant processes, concepts, and rela- tionships. Assessing the subjective com- ponent of written problems requires judgment. The instructor may ask some of the following questions:

1. When the student has a choice, are some approaches to solving a problem

more appropriate than others?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2. When a solution has several steps

that build on each other, how should the instructor treat arithmetic or conceptual errors that were made early in the process and that make the objective answer incorrect?

3. Most written problems have many calculations: Should math errors carry the same weight as conceptual errors?

Although the answers to these ques- tions and their impact on actual grading are at the discretion of the individual instructor, the prevailing belief is that these judgments should be made in advance and used consistently so that the assessments are fair and under- standable (Hickey, 1999). Two meth- ods of grading partially correct written problems are partial credit and grading

rubrics.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Grading Methods: Partial Credit

To assign partial credit, the instructor examines the subjective elements and determines the student’s level of success in applying them. For example, if the instructor believes that a 10-point prob- lem is 60% correct, 6 points may be assigned. The value of partial credit is that it acknowledges the correct portion of the answer. In addition, the points assigned to different problems are equivalent so that they can be added to produce the total grade. However, dif- ferences among written problems may lead to inconsistency in grading that

would make the total points assigned

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

320 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessdifficult to explain (Thompson

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Senk,1998, p. 788).

Grading Methods: Scoring Rubrics

Instructors design scoring rubrics to mitigate grading inconsistency caused by subjectivity. They are sets of prede- termined criteria that indicate the degree of success that a student demonstrates in working a written problem (Hickey, 1999; Thompson & Senk, 1998). Rubrics have demonstrated strong inter- rater reliability (Senk, 1985). However, the literature on rubrics provides no guidance on the assignment of grades. Two categories of rubrics are holistic and analytic.

Holistic rubrics. Holistic rubrics are general success criteria that can be applied to any written problem (Thomp- son & Senk, 1998). An instructor prede- termines the degree of correctness based on the percentage of possible mistakes and the weight of the mistakes (i.e., con- ceptual vs. math) and sets a cut-off point that identifies a correct answer. On a 6-0 or 4-0 scale, correct answers receive higher scores and incorrect answers receive lower scores. Holistic rubric scores are consistent within and among questions so that the instructor can add the scores to arrive at the total. They also make grades explainable.

Analytic rubrics. Used for specific problems, analytic rubrics are especial- ly useful for grading open-ended ques- tions. To draft an analytic rubric, the instructor lists all relevant ’ concepts

needed to answer the question and matches them with all possible responses. All combinations of con- cepts and responses are ranked and assigned scores. Using an analytic rubric can make grading consistent and explainable. Analytic rubrics also make giving feedback easier because the instructor has already considered all possible outcomes (Hickey, 1999). Rubrics given with an assignment can be used as a checklist, and they may be used by students to grade their peers’ work. Student comments indicate that these practices are valuable to their learning (Petit & Zawojewski, 1997; Thompson & Senk, 1998).

The literature reveals a large body of knowledge dealing with grading; how- ever, this knowledge generally origi- nates from instructors. In this study, we solicited input from university market- ing and accounting students to investi- gate their perceptions on grading. We formulated the following research question: What factors regarding facul- ty members’ grading of essays and quantitative problems specifically irri-

tate students?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Method

Sample

We conducted this study at the Col- lege of Business at a regional public Midwestern university. At the time, total enrollment at the College was 2,979, 4 1 % of these students were female, and the average age was 22. Students sur-

veyed about essays were juniors taking the introductory marketing class required by all business majors. This marketing class required substantial marketing strategy essay reports. Stu- dents surveyed about written quantita- tive problems were sophomore and junior accounting majors taking an advanced cost accounting class required of all majors. This accounting class required students to do written prob- lems for homework and on exams. The classes were 42.3% female with 96.6% traditional students.

Survey and Data Collection

The survey instruments consisted of one item. For essay questions, we asked students to complete the following statement: “It really imtates me when an instructor grades my papers and.

. . .”

For written problems, we asked them to complete the statement “It really irri- tates me when an instructor grades my written problems and..

.

.”

The adminis- trator explained the purpose of the research after handing out the surveys. The students were told that their responses would be kept anonymous and that completing the survey was optional. In addition, to obtain a variety of responses, the administrator told the students to think of their entire educa- tional experience, not just the particularclass in which the survey was being given. We distributed 232 surveys on essay grading, and 217 students com-

pleted the statement for a response rate

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of 94%. We distributed

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

53 surveys onwritten problems, and all students com- pleted that statement for a response rate

of 100%. However, we discarded three

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of the responses because they were too

specific to the class to be generalizable.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Data Analysis

We reviewed the responses for the surveys and identified general cate- gories for each (i.e., 15 categories for essay grading and 12 categories for written problems) plus an “other” cate- gory. For each set of responses, two graduate students took the original com- ments and placed each comment in one or more of the categories. In some cases, comments made multiple points, so we placed them in two or more cate- gories. We calculated the interrater reli- ability scores by dividing the number of times the graduate students made the same classification by the total number

of responses. Scores were 86.9% for essays and 84.6% for written problems. When raters disagreed on the catego- rization of particular student comments, we made the final decisions on which

categories best suited the comments.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Results

Students’ Comments on Grading of Essays

Of the 15 initial categories, 10 had more than five comments and the remaining comments composed the other category, leaving 11 total group- ings for comments (see Table 1).

The data in Table 1 show that the most frequent student complaint con- cerning essay grading was that instruc- tors provided either minimal or no feed- back with the grade. Over one third of students were irritated by this practice. The second most frequent complaint was that instructors provided only criti- cism, when students would have appre- ciated some positive feedback as well. Tied for third and fourth in frequency were the perceptions that (a) instructors did not give suggestions for improve-

TABLE 1. Students’ Comments on Gradlng Essays

Frequency

Comment No.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

%The instructor gave minimal or no feedback. The instructor gave The instructor only gave negative comments or criticism. The instructor did not tell me how to improve.

The instructor did not explain the points or grading system. The instructor did not supply grading criteria.

The instructor’s handwriting was not readable.

The instructor’s comments were based on opinions rather than The instructor made too many marks on my paper. The comments The instructor did not read carefully or spend time in grading The instructor did not return papers in a timely manner.

The instructor’s comments were too vague. I could not determine

Other

no explanation for the grade given. objective criteria.

were excessive. my paper.

what the instructor wanted. Total

90

39

25 25

17

7

7

6 5

5

23 249

36.1 15.7 10.0

10.0

6.8

2.8 2.8 2.4 2.0 2.0 9.2

100

ment for subsequent assignments and (b) students did not understand how points or grades were determined. Remarks that instructors’ comments were not objective were related to this complaint. Apparently, students per- ceived that opinions played too great a role in grading. Indecipherable hand- writing was a problem for almost 7% of students. Contrary to the often-voiced opinion that instructors did not give enough guidance in their comments, a small percentage of students felt that instructor’s “bled red all over” papers, or that their comments were excessive. Timing related to grading and feedback arose as another issue. Some students felt that instructors did not spend ade- quate time in grading their papers, and some felt a certain arbitrariness in the grading process. Students also com- plained that they did not receive their papers and grades in a timely manner. The “other” category included, among others, the following complaints:

The assignment was not clear from the start.

The instructor used terms and sym- bols that I did not understand.

The instructor’s comments were disrespectful of me as a person.

The grading did not appear consis- tent. Other students with similar papers had different grades.

Students ’ Comments on Grading Written Problems

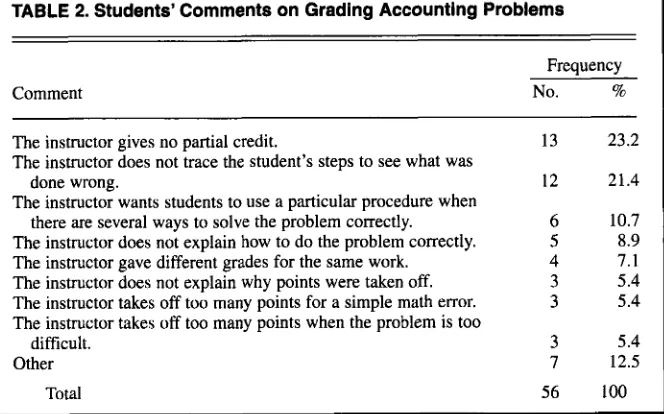

Of the 12 initial categories, 8 had three or more comments and the remaining comments composed the other category, leaving 9 total groupings for comments. The results are reported in Table 2.

The data in Table 2 show that the stu- dents’ most frequent complaint regard- ing the grading of written problems was instructors’ failure to assign partial credit. More than 23% indicated that instructors’ all-or-nothing approaches to grading irritated them. The second most frequent complaint dealt with instructors’ not following the students’ steps to identify what they did correctly. This compliant was related to the first most frequent complaint, indicating that students considered receiving credit for what they did correctly important. This response may also suggest that students would appreciate having instructors spend more time and take more care in grading their work. The third most fre- quent complaint related to instructors’ expectation that students use one partic- ular method to solve problems when there are other acceptable methods. The fourth most frequent irritation cited inconsistency in grading and may also indicate students’ desire that instructors take more care in grading work. The fifth, sixth, and seventh most frequent

July/August

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2003 321TABLE 2. Students’ Comments on Grading Accounting Problems

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Comment

Frequency

No.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

%The instructor gives no partial credit.

The instructor does not trace

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

the student’s steps to see what wasdone wrong.

The instructor wants students to use a particular procedure when

there are several ways to solve the problem correctly.

The instructor does not explain how to do the problem correctly. The instructor gave different grades for the same work.

The instructor does not explain why points were taken off.

The instructor takes off too many points for a simple math error. The instructor takes off too many points when the problem is too Other

difficult.

Total

13 23.2

12

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

21.46 10.7

5 8.9

4 7.1

3 5.4

3 5.4

3 5.4

7 12.5

56 100

complaints each had three responses. Students indicated that they were irritat- ed when (a) instructors did not explain why points were taken off, (b) instruc- tors took off too many points for small math errors, and (c) the problem was too difficult. The “other” category included the following complaints:

Points were taken off for mistakes in homework when students should get full credit for effort.

Points were taken off when the stu- dent got the answer right but did not show all the work.

The requirements were unclear. The comments were indecipherable. The responses indicate that students were irritated with instructors’ formal or informal methods of assigning points to problems that were partially correct. Many also wanted instructors to provide more helpful feedback. The data also suggest that students wanted to receive credit for the knowledge that they demonstrated.

Discussion and Strategies for Improvement

The student comments about factors in grading that irritated them fall under two broad categories: lack of fairness and inadequate feedback. Regarding fairness, more than half of the com- ments on written problems indicated that students were irritated when they could not understand the instructor’s assignment of partial credit, when they

believed that the partial credit given did not represent adequately what they actually knew, and when they received no partial credit. We obtained similar comments regarding partial credit and not understanding how the grade was determined in the survey regarding essays. Students were irritated when grades seemed to be given based on opinion rather than fact and when they believed that the instructor was not con- sidering each student’s work separately. Students in both groups indicated that they wanted faculty members to take adequate time for reading students’ work to determine whether they under- stood the material. These comments support Walvoord and Anderson (1998) and Thompson and Senk (1998), who suggested that students want to under- stand their grades. This result also seems to suggest that students may pre- fer objective grading.

Students also indicated irritation with what they perceived as too much emphasis on small arithmetic errors. This perception is similar to the “grarn- mar vs. content” view given by students regarding essay grades. These com- ments support Tchudi (1986), who sug- gested that content should be given more weight than “literary excellence” in the grading process. The students’ comments on fairness suggest the fol- lowing strategies for improvement:

Begin with clear objectives in eval- uation of each assignment and commu- nicate them to the students.

Use grading rubrics, grade sheets, and/or grading matrices.

Regarding feedback, students indicat- ed the need to understand what they did wrong and how they might improve. For essays, irritations included receiving no comments, only negative comments, too many comments, or vague comments, suggesting that instructors grading essays could achieve balance by (a) addressing only major essay content problems and (b) placing less emphasis on grammar (Walvoord, 1986). In addi- tion, the comments underscore the value of pointing out what the student did right (Tchudi, 1986; Walvoord, 1986). Other irritations that dealt with more mechanical aspects of feedback includ- ed “not being able to read the instruc- tor’s hand writing” and “not receiving the graded assignment in a timely man- ner.’’ Regarding answers to written problems, students cited complaints about instructors’ comments that failed to tell them “where they went wrong” or to “show them what should have been done.” The students’ comments suggest the following strategies for improve- ment regarding giving feedback:

Give thoughtful, constructive com- ments.

Watch your penmanship.

Finally, the students’ overall message seems to suggest a desire for faculty members to show professionalism and respect for them as fellow scholars. Regarding this concern, the following strategies for improvement seem appropriate:

Maintain objectivity.

Improve grading skills by attending assessment workshops.

Conclusion

Faculty members are aware that grades and grading methods are impor- tant to students. For guidance on grad- ing, many faculty members consider their own experience as students, solicit advice from colleagues, and scan the education literature. Much research has focused on suggestions about what and how to grade and how to provide mean- ingful feedback. However, the literature has provided no systematic investiga-

322

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for BusinesszyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

[image:6.612.53.385.52.259.2]tion that solicits guidance on grading Petit, M.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Zawojewski, J. (1997). Teachers and Tchudi, S. N. (1986). Teaching writing in the con-zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

" " "

students learning together about assessing

problem solving. The Mathematics Teacher, National Education Association.

tent areas: College level. Washington, DC:

from students. This study fills the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

gap.zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

REFERENCES

Angelo, T. A,, & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom

assessment techniques: A

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

handbook for collegeteachers (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hickey, M. (1999). Assessment rubrics for music composition. Music Educators Journal, 85(4),

2 6 3 5 .

90(6), 412471.-

Senk, S. (1985). How well do students write geometry proofs? Mathematics Teacher, 78(6),

448-456.

Speck, B. W., & Jones, T. R. (1998). Direction in the grading of writing. In F. Zak & C. Weaver

(Eds.), The theory and practice

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of grading writ-ing (pp. 17-29). Albany, N Y State University of New York Press.

Thompson, D., & Senk, S. (1998). Using rubrics in high school mathematics courses. Mathemat- ics Teacher; 91(9), 1 8 6 7 9 3 .

Unwin, T. (1990). 2.1 or not 2.1 ? The assessment of undergraduate essays. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, I4(March), 31-39.

Walvoord, B. (1986). Helping students write well (2nd ed.). New York: Modem Language Asso- Page, E. €3. (1994). Computer grading of student

prose, using modern concepts and software.

Journal of Experimental Education, 62(Win-

ter), 127-143. 13-78. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Squires, B. (1999). Conventional grading and the delusions of academe. Education for Health: Change in Training and Practice, 12(March),

ciation.

Walvoord, B., & Anderson, V. J. (1998). Effective grading: A tool for learning and assessment.

July/Augusr 2003

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

323