Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:50

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Specialized Accreditation of Business Schools: A

Comparison of Alternative Costs, Benefits, and

Motivations

Robert H. Roller , Brett K. Andrews & Steven L. Bovee

To cite this article: Robert H. Roller , Brett K. Andrews & Steven L. Bovee (2003)

Specialized Accreditation of Business Schools: A Comparison of Alternative Costs, Benefits, and Motivations, Journal of Education for Business, 78:4, 197-204, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309598601

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309598601

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 73

View related articles

Specialized Accreditation of

Business Schools: A Comparison

of

Alternative Costs, Benefits, and

Motivations

ROBERT H. ROLLER

BRElT K. ANDREWS

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

LeTourneau University

Longview, Texas

he past decade has witnessed a

T

steady increase in the number of institutions receiving specialized accreditation for their business pro- grams. Until 1988, only one business accreditation association existed: the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), now known as AACSB International-the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. Since then, two newer business accreditation associa- tions have been formed: the Association of Collegiate Business Schools and Pro- grams (ACBSP) and the International Assembly for Collegiate Business Edu- cation (IACBE), each of which now has over 100 accredited baccalaureate degree institutions. Despite the interest in and growth of specialized accredita- tion in business, there has been no sys- tematic comparison of the perceived costs and benefits of, and motivations for, specialized accreditation across these three accrediting associations.Previous researchers have discussed a number of benefits of specialized busi- ness accreditation. Accreditation pro- vides stakeholders with certification that a program meets or exceeds mini- mum standards of excellence (MacKen- zie, 1964; Pastore, 1989), ensures a uni- formity of educational standards (Stettler, 1965), and helps high quality students identify high quality programs

ABSTRACT. In this study, the

authors surveyed

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

122 deans andchairs of business schools to examine the costs and benefits of specialized accreditation and the schools’ motiva- tion for seeking it. The respondents represented nonaccredited schools and ones accredited by any of the three business accrediting associa- tions. The authors discuss the benefits

of accreditation and its relationship to program goals, program competitive- ness, and student learning. Their results showed significant differences across the four categories represent- ing schools accredited by each of the three associations and the nonaccred- ited institutions.

STEVEN L. BOVEE

Roberts Wesleyan College

Rochester,

New York(Pearson, 1979; Posey

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Parker, 1989).AACSB accreditation has been shown to influence positively the employment prospects of accounting graduates, although it was not one of the top fac- tors considered by CPA recruiters and controllers (Hardin & Stocks, 1995).

Specialized business accreditation also affects a number of factors impor- tant to business faculty and administra- tors. Levernier and Miles (1992) com- pared AACSB-accredited business programs with programs that were not AACSB accredited and found that AACSB accreditation had a positive effect on business professors’ salaries and increased crossdisciplinary salary differentials. AACSB accreditation also increases the importance of certain forms of scholarly activity (e.g., the

scholarships of discovery and applica- tion), publishing in top journals, and paid consulting (Srinivasan, Kemelgor,

& Johnson, 2000).

Our study was based on the concept of cost-benefit analysis, which assumes that a school of business’ will pursue specialized accreditation when the per- ceived benefits exceed the perceived costs. This assumption implies that each institution consciously or subconscious- ly assesses the impact of specialized accreditation on its goals and on those of its school of business. A school uses a similar cost-benefit analysis to deter- mine which business accreditation asso- ciation to affiliate with. Accordingly, we set out to examine the goals, benefits, and costs of specialized business accreditation, exploring the following questions:

Which business schools have received specialized accreditation, with whom, and why?

For business schools that have not received specialized accreditation, what stage of the accreditation process are they in? If they are not pursuing accred- itation, why not?

What are the perceived benefits, costs, and motivations associated with specialized business accreditation, and do these perceptions influence accredi-

tation association choices?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MarcWApril2003 197

Does the size, organizational struc- ture, or program mix offered by a school of business influence its accreditation

choices?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A Brief History of Business Accreditation

The AACSB is the original business accreditation association, and for its first 70 years of existence, it was the only business accreditation association (Henninger, 1998b). Before the mid- 1990s, AACSB institutions tended to be large and research oriented. After the adoption of new mission-based stan- dards, institutions with teaching-orient- ed missions could become members of the AACSB (Jantzen, 2000; McKenna,

Cotton,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Van Auken, 1995). The cost, rigor, and prescriptive tendencies of theAACSB accreditation standards, how- ever, made accreditation challenging for many smaller teaching-oriented institu- tions. The ACBSP was formed in 1988 to make it easier for institutions with a teaching-oriented mission to receive business accreditation (Henninger, 1998b). However, the ACBSP still had a largely prescriptive, input-based approach to accreditation. Many of the ACBSP standards were similar to those of the AACSB but were somewhat more teaching oriented (Bovee, Roller, &

Andrews, 2000). The ACBSP’s inten- tion was to serve institutions that emphasized teaching more than research, to allow for greater percent- ages of faculty members with terminal degrees in related fields, and to broaden the definition of scholarly activity to include instructional development (ACBSP, 1996). The ACBSP also estab- lished accreditation for 2-year business programs and remains unique among the three business accrediting associa- tions in doing so. More than half of the

ACBSP-accredited programs are at

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2-year colleges.

Possibly in response to the competi- tion from the ACBSP, the AACSB adopted mission-oriented standards, making it more possible for teaching- oriented institutions to receive accredi- tation (Henninger, 1998, McKenna et al., 1995). These standards, while emphasizing mission differences and increasing the emphasis on outcomes

assessment, were still largely prescrip- tive and expensive. Nevertheless, the new standards have gradually allowed the AACSB to become more diverse: Smaller schools; teaching-oriented schools; and schools without doctoral programs, with larger numbers of part- time faculty members, with higher minority enrollments, or with lower GMAT scores are making up a larger percentage of AACSB candidates for accreditation (Jantzen, 2000).

In 1998, a third accrediting associa- tion-the IACBE-was formed in response to the ACBSP’s perceived emphasis on prescriptive standards and lack of flexibility. Some institutions, often those with various types of non- traditional programs, felt that the ACBSP’s approach to accreditation was too rigid. The IACBE’s approach to accreditation is based on a rigorous out- comes assessment and continuous improvement process; inputs are impor- tant only to the extent to which they affect outcomes. Although all of the business accrediting associations (as well as the regional college accredita- tion associations) have increasingly moved toward outcomes-assessment- oriented accreditation processes, the IACBE is currently the most outcomes- assessment-oriented of the three busi- ness accrediting associations.

In what appears to be a response to competition from the IACBE, the ACBSP adopted an alternative route to accreditation based on Malcolm Baldrige quality standards. The rigor involved in the alternative process apparently exceeds that of the standard route to ACBSP accreditation, and few institutions have attempted it.

The development of newer business accrediting associations affects the competitive dynamics of collegiate business education. One result is that the prestige associated with specialized accreditation has been extended to an increasing number of institutions. This situation comes with the risk that the value of specialized education will decrease as the supply of accredited institutions increases. Business accredi- tation is increasingly a differentiated product, with each association offering unique benefits and costs that interface differently with each institution. The

AACSB, ACBSP, and IACBE have dif- ferent priorities and use different evalu- ative processes and measures.2 These factors affect both the benefits and the costs of professional accreditation.

Method

We developed a questionnaire to gather both demographic and attitudinal variables from the business dean of each institution in the sample (a copy of the questionnaire is available from the authors). We identified a random sam- pling of AACSB-accredited, ACBSP- accredited, IACBE-accredited, and nonaccredited institutions, for a total of 41 1 institutions. We contacted each dean via telephone to introduce the research and gain cooperation in the survey. We then sent a copy of the sur- vey via FAX. Respondents returned their surveys either by fax or mail. Of the 41 1 surveys, 122 usable ones were returned, resulting in a 29.6% response rate.

Results

Demographically, the colleges or uni- versities had a mean total enrollment of 5,940 and a mean business school enrollment of 1,090. Nontraditional stu- dents played a large part in the business school enrollments: The mean nontradi- tional business student enrollment was 473 (43.4% of the mean business school enrollment).

Degree options were plentiful and varied widely among the schools. As a population, the schools offered 5 associ- ate degree programs, 137 bachelor’s degree programs, 94 master’s degree programs, and 10 doctoral degree pro- grams. From most to least popular, the subject areas offered were accounting, business administration, management, marketing, finance, management infor- mation systems, international business, economics, human resource manage- ment, small business/entrepreneurship, sports management, business education, industrial management, and business communications.

Approximately one fourth (24%) of the respondents did not have specialized business accreditation. Of responding institutions, 13.5% were accredited by

198

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinesszyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

the AACSB, 33.7% were accredited by the ACBSP, and 27.9% by the IACBE. We asked the institutions without busi- ness accreditation to report their accred- itation status (see Table 1). Only 30% of these programs were not in some stage of the accreditation process.

The organizational structure of the business school units varied widely. Fifty percent reported being organized as a school of business, 16% as a divi- sion of business, and 26% as a business department. Sixty-two percent of the schools reported having some type of nontraditional delivery (e.g., on-line, compressed, distance learning) format for business degree programs. Of these schools, 62% administered these pro- grams through the school of business. The remaining 38% administered non- traditional programs externally from the school/division of business. Whether or not a school delivered its business pro- grams via some type of nontraditional format did not have a significant posi- tive impact on enrollment-except for the effect on total nontraditional enroll-

ment

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( t =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2.744, p = .008). The patternof nontraditional programs varied across the accrediting associations. In all the accredited categories, more respondents reported having nontradi- tional programs than not having them. However, the difference was most pro- nounced for IACBE respondents, who overwhelmingly reported having non- traditional programs (see Figure 1).

Respondents rated several perceived benefits of professional accreditation for their programs (see Table 2). Con- tinuous improvement benefits received the highest ratings, whereas resource bargaining leverage benefits received the lowest.

In Table 3, we show respondents' rat- ings of the importance of a variety of goals for their programs. Each of the listed goals was considered important: The lowest-rated goal, faculty scholarly activity, received a mean rating of 3.6 on a 5-point scale of importance.

With a mean of 4.01

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(0 = 1.19) on a5-point scale, respondents indicated that professional accreditation was very important for ensuring program com- petitiveness. Results for this item varied significantly across the accrediting associations: The mean for AACSB

1

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 1. Current Status of Respondent Institutions Without BusinessAccreditation

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( N=

30)Status No.

Official candidate for accreditation 4

In discussions with an accrediting body about becoming a candidate 6 In discussions with the college administration about becoming a candidate 5 In discussions with business faculty about becoming a candidate 6

Not considering or discussing accreditation at this time

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

91 %

0

z

UI

C

Q)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c

z

B

E

UI

Yes No

AACSB

ACBSP

IACBE

H

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1

NonalignedPresence of nontraditional programs

FIGURE 1. Presence of nontraditional programs among AACSB, ACBSP, IACSB, and nonaligned respondent institutions.

TABLE 2. Respondents' Perceptions of Benefits of Business Accredita- tion ( N = 122)

I

Variable M SDI

Accountability for program improvements 4.31 .8 1 Opportunities to share techniques/successes/challenges with other

institutions facing similar issues 3.95 .86 Marketing advantages 3.88 1.03 Faculty recruitment advantages 3.75 1.06 Recognition as a superior (elite) institution 3.66 1.01 Increased bargaining leverage for university resources 3.36 1.31 Increased bargaining leverage for faculty compensation 3.01 1.25

I

Note. Respondents scored degree to which accreditation benefited variables on a 5-point scale

ranging from 1

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(ofno benefit) to 5 (ofgrear benefit).respondents (4.43) was higher than that for ACBSP respondents (4.16), and the mean for ACBSP respondents was high- er than that for IACBE respondents (3.89). These data were based on an analysis of variance ( F = 3.675, p =

.014).

Respondents who rated professional accreditation as being more important for ensuring program competitiveness rated the following benefits of accredi- tation significantly higher than did those

who rated it as less important for com- petitiveness: accountability for program improvements ( t = 6.34, p < .OOO); mar- keting advantages ( t = 4.95, p < .OOO); faculty recruitment advantages ( t =

5.18, p < .OOO); increased bargaining leverage for university resources

( r

=2.44, p = .016); recognition as a superi- or institution ( t = 3.73, p = .OOO); and opportunities to share techniques, suc- cesses, and challenges with others fac- ing similar issues ( t = 2.70, p = .008).

MarcWApril2003 199

TABLE 3. Respondents’ Perceptions of Importance of Their Business

Schools’ Goals

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( N =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

122)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Variable

Excellence in classroom instruction

Recruiting quality faculty

Continuous program improvement

Excellence in advising students

Academic reputation of the program Reputation in the business community Survival of the program

Placement of graduates in top jobs Professional development of faculty

Increasing enrollment in the program Increasing faculty compensation Community service/outreach

Faculty scholarly activity

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M SD

4.81 .67 4.54 .79 4.55 .68 4.46 .82 4.37 .81 4.40 .82 4.24 I .06 4.14 .92 4.15 .79 3.98 1.03 3.98 1.06 3.7 1 .92

3.63 1.04

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. Respondents scored goal importance on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (very unimportant)

to 5 ( v e v importanr).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Additionally, the respondents who rated professional accreditation as being more important for ensuring program competitiveness and those who rated it as less important differed significantly on the perceived importance of the fol- lowing program goals: reputation in the business community ( t = 3 . 0 4 , ~ < .003), excellence in classroom instruction ( t =

1.98, p < .050), faculty scholarly activi-

ty ( t = 2.58, p < .Oll), professional development of faculty ( t = 2.03, p <

.044), academic reputation of program (t = 2.47, p < .015), survival of the pro- gram (? = 2.29, p < .023), and recruiting quality faculty ( t = 2.06, p < ,041).

Respondents rated the importance of accreditation in ensuring the quality of student learning as somewhat lower than its importance in ensuring program

competitiveness, with a mean of 3.71

(ts

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= 1.20) on a 5-point scale. These results also varied across the accrediting asso- ciations: According to an analysis of variance ( F = 4.339, p = .006), the AACSB mean (4.10) was higher than that for the ACBSP (3.94), and the ACBSP mean was higher than that for the IACBE (3.62).

Compared with those who responded that professional accreditation was less important for ensuring the quality of student learning, those who perceived it as more important for this goal scored higher on the following benefits of accreditation: accountability for pro- gram improvements ( t = 5.72, p < .OOO),

faculty scholarly activities ( t = 2.87, p < .005), faculty recruitment advantages (t

= 3 .01, p = .003), increased bargaining leverage for university resources ( t =

2.45, p = .016), and opportunities to share techniques/successes/challenges with others facing similar issues ( t =

2.69, p = .008). These respondents also reported four goals as being more important than did those who responded that professional accreditation was less important for ensuring the quality of student learning: increasing faculty scholarly activity ( t = 2.89, p = .005),

academic reputation ( t = 2.00, p = .048), continuous program improvement ( t =

2.24, p < .027), and reputation in the business community ( t = 2 . 1 5 , ~ = .033). We found only a few differences in perceived benefits of accreditation across the accrediting associations rep- resented in our sample. AACSB respon- dents gave higher ratings to faculty recruitment advantages than did ACBSP respondents (t = 2.16, p = .036) or IACBE ( t = 5 . 5 2 , ~ < .001) respondents, and ACBSP respondents gave higher ratings to faculty recruitment advan- tages than did IACBE respondents ( t =

3.17, p = .002). AACSB respondents gave higher ratings to marketing advan- tages than did IACBE respondents ( t =

3.19, p < .001). Meanwhile, ACBSP respondents gave higher ratings to increased bargaining leverage for uni- versity resources than did IACBE respondents ( t = 2.27, p = .027).

In terms of goals, AACSB respon- dents rated the importance of faculty scholarly activity higher than did ACBSP ( t = 2.912, p = .005) and

IACBE (t = 4.76, p < .001) respondents, but there was no significant difference between ACBSP and IACBE respon- dents. AACSB respondents also rated the importance of excellence in advising lower than did ACBSP

( r

= -2.89, p =.006) and IACBE ( t = -2.09, p = .043) respondents, but there was no difference between ACBSP and IACBE respon- dents’ ratings, ACBSP respondents rated the goal of recruiting quality fac- ulty as more important than did IACBE respondents ( t = 2.09, p = .043).

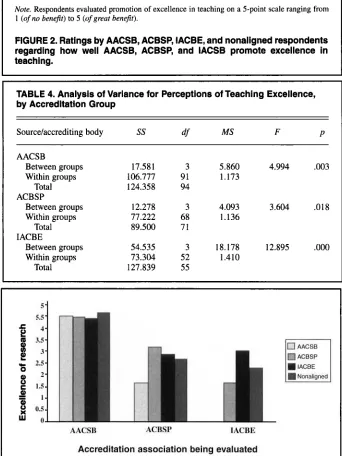

Using analysis of variance, we com- pared respondents’ perceptions of teach- ing excellence, research excellence, and flexibility of the accreditation process across the three accreditation categories and the nonaligned one. The results illustrated in Figure 2 (with ANOVA results in Table 4) indicate that mem- bers of each accrediting association per- ceived their own association as promot- ing more excellence in teaching than the other accrediting associations. Interest- ingly, no AACSB-accredited respondent ranked the IACBE on this factor. ACBSP institutions ranked the ACBSP highest on promoting excellence in teaching, the AACSB second highest, and the IACBE third. Nonaligned insti- tutions mirrored this pattern of results.

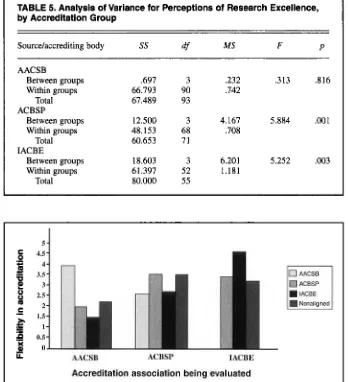

We also compared perceptions of excellence in research across the sample (see Figure 3 and Table 5). All respon- dent groups perceived the AACSB as promoting excellence in research. Members of the ACBSP and IACBE each perceived their own association as promoting more excellence in research than the other. Meanwhile, AACSB respondents rated the ACBSP low on promoting excellence in research and did not rate the IACBE.

We also asked respondents to rate the three accrediting associations on their flexibility in accreditation (see Figure 4 and Table 6). Compared with respon- dents from the ACBSP, the IACBE, and nonaligned institutions, respondents from AACSB institutions saw the AACSB as being significantly more flexible. All respondents except those from AACSB institutions rated both the

200 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessAACSB

ACBSP

IACBE

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

i

NonalignedzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Accreditation association being evaluated

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. Respondents evaluated promotion of excellence in teaching on a 5-point scale ranging from

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 (ofno benefit) to 5 (ofgreat benefit).

FIGURE 2. Ratings by AACSB, ACBSP, IACBE, and nonaligned respondents regarding how well AACSB, ACBSP, and IACSB promote excellence in teaching.

TABLE 4. Analysis of Variance for Perceptions of Teaching Excellence, by Accreditation Group

I

Sourcelaccrediting bodyss

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

dfzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MS F PAACSB

Between groups Within groups

Total ACBSP

Between groups Within groups

Total IACBE

Between groups

Within groups Total

17.581 106.777 124.358

12.278 77.222 89.500

54.535 73.304 127.839

3 5.860 4.994 .003

91 1.173

94

3 4.093 3.604 .018

68 1.136

71

3 18.178 12.895

.ooo

52 1.410

55

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

AACSB ACBSP IACBE

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

ACBSPI

IACBENonaligned

Accreditation association being evaluated

Note. Respondents evaluated promotion of excellence in research on a 5-point scale ranging from

1

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(ofno benefit) to 5 (of great benefit).FIGURE 3. Ratings by AACSB, ACBSP, IACBE, and nonaligned respon- dents regardlng how well AACSB, ACBSP, and IACSB promote excellence in research.

ACBSP and IACBE as having more flexibility in accreditation than the AACSB. IACBE institutions perceived the IACBE as having more flexibility than either the AASCB or ACBSP.

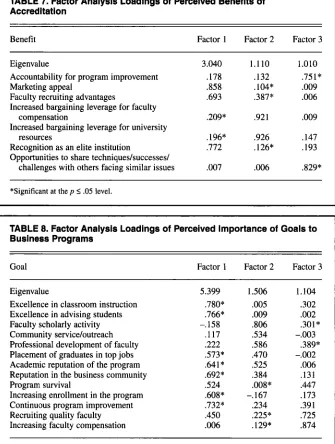

To explore commonalities in accred- itation benefits, we performed a factor analysis (with varimax rotation) on the perceived benefits of business accredi- tation. The analysis revealed three main factors (see Table 7). The first factor, External ReputationICompetitiveness Benefits, loaded highly on enhanced student marketing appeal, enhanced recognition as an elite institution, and faculty recruiting advantages. Respon- dents who rated these benefits as important appeared to view accredita- tion as a way to enhance the external appeal of their business programs. The second factor, Resource Benefits, loaded highly on increased leverage for faculty compensation and increased bargaining leverage for university resources. These schools apparently use accreditation as a means to acquire needed resources. The third factor, Pro- gram Development Benefits, loaded highly on accountability for program improvement and opportunities to share techniqueslsuccesseslchallenges with others. These business programs rely on accreditation for their developmen- tal benefits. We found no significant differences in these factors across the accrediting associations.

To explore commonalities in goals, we performed a factor analysis (with varimax rotation) on the perceived importance of program goals. This analysis revealed three main factors (see Table 8). The sets of goals included in

these factors appear to describe three different paradigms or orientations of programs. The first factor, Balanced Growth Orientation, loaded highly on the following goals: reputation in the business community, excellence in classroom instruction, academic reputa- tion of the program, continuous pro- gram improvement, excellence in advis- ing students, placement of graduates in top jobs, increasing enrollment in the program, and program survival. Schools with a strong emphasis on these pro- gram goals appear to be pursuing a growth strategy that balances quality and a teaching orientation with cost

MarcWApril2003 201

[image:6.612.50.388.48.191.2] [image:6.612.45.387.203.659.2]TABLE 5. Analysis of Variance for Perceptions

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of

Research Excellence, by Accreditation GroupSource/accrediting body

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ss

df MS F PAACSB

Between groups

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.697 3 .232 .313 3 1 6Within groups 66.793 90 .742

Total 67.489 93

ACBSP

Between groups 12.500 3 4.167 5.884

.oo

1Within groups 48.153 68 .708

Total 60.653 71

IACBE

Between groups 18.603 3 6.201 5.252 .003

Within groups 61.397 52 1.181

Total 80.000 55

Accreditation association being evaluated

ACBSP

IACBE

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. Respondents evaluated flexibility in accreditation on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (of no

benefit) to

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 (of great benefit).FIGURE 4. Ratings by AACSB, ACBSP, IACBE, and nonaligned respondents regarding how flexible AACSB, ACBSP, and IACSB are in accreditation.

TABLE 6. Analysis of Variance of Perceived Flexlbility In Accreditation, by Accreditation Group

Source/accrediting body

ss

df MS F PAACSB

Between groups Within groups

Total ACBSP

Between groups Within groups

Total IACBE

Between groups Within groups

Total

48.953 112.335 16 1.289

9.633 102.976 112.609

20.125 8 1.800 101.925

3 16.318 12.492 .Ooo

86 1.306

89

3 3.21 1 2.027 .119

65 1.584

68

3 6.708 4.018 .012

49 1.669

52

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

effectiveness. The second factor, Research Orientation, loaded highly on faculty scholarly activity and profes- sional development of faculty. These programs appear to put a premium on scholarly contributions. The third factor, Resource-Challenged Orientation, loaded highly on increasing faculty compensation, recruiting quality facul- ty, and program survival. Respondents with these goals appear to be struggling with resource issues such as attracting and retaining qualified faculty. We found no differences across accrediting associations on these factors.

Discussion

We should note one limitation of our study: the relatively low number of respondents in the AACSB-accredited portion of the sample. This limitation is a result of a low response rate from deans of AACSB-accredited schools, despite our repeated attempts to contact them. However, because previous researchers have found that deans of accredited schools hold highly homoge- neous views (Cotton, McKenna, Van Auken, & Yeider, 1993; McKenna et al., 1995), this limitation may have had a greater impact on statistical power than on the generalizability of the findings.

As we examined the history of busi- ness accreditation, we suggested that the entrance of newer accrediting asso- ciations might be changing the compet- itive landscape, resulting in an increas- ingly differentiated approach to business accreditation. Our results sup- port this proposition in some ways, but not in others. For example, deans of AACSB-accredited schools were appar- ently aware of the competition from the ACBSP but not of that from the IACBE; however, deans from nonaccredited schools and those accredited by the ACBSP and IACBE were apparently aware of the competition effect from all three accrediting associations.

Our findings appear to support the view of the AACSB as the most presti- gious of the associations, not only because it is the oldest and largest of the three, but also because of its promotion of excellence in research. Consistent with this perception, AACSB-accredit- ed respondents placed the most empha-

202 Journal of Education for Business

[image:7.612.44.392.49.431.2]TABLE 7. Factor Analysis Loadings of Perceived Benefits of

Accreditation

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Benefit Factor 1 Factor

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2 Factor 3Eigenvalue

Accountability for program improvement Marketing appeal

Faculty recruiting advantages

Increased bargaining leverage for faculty

Increased bargaining leverage for university

Recognition as an elite institution

Opportunities to share techniqueslsuccessesl compensation

resources

challenges with others facing similar issues

3.040 1.110 .178 .I32 .858 .104* ,693 .387* .209* .921 .196* .926 ,772 .126* .007 .006

1.010

.75 1

*

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.009 .006 .009 .147 .I93 .829*

*Significant at the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

pzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2 .05 level.TABLE 8. Factor Analysis Loadings of Perceived Importance of Goals to Business Programs

Goal Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

Eigenvalue

Excellence in classroom instruction Excellence in advising students Faculty scholarly activity Community service/outreach Professional development of faculty Placement of graduates in top jobs

Academic reputation of the program Reputation in the business community Program survival

Increasing enrollment in the program Continuous program improvement Recruiting quality faculty Increasing faculty compensation

5.399 .780* .766*

-.

158 ,117 .222 .573* .641* .692* ,524 .608* .732* .450 .0061 SO6

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.005

.009 .806 ,534 .586 .470 .525 .384 .008* .234 .225* .129*

-.

I671.104 .302 .002 .301*

-.003

.389* -.002

.006 .131 .447 .173 .39 1

.725 .874

*Significant at the p 5.05 level.

sis on faculty scholarly activity. AACSB respondents did not view research excellence as detracting from classroom excellence. Non-AACSB respondents, however, saw the AACSB’s emphasis on excellence in research as interfering with excellence in the classroom and in advising. But most respondents agreed that AACSB accreditation benefits the faculty recruitment process, bargaining leverage for resources, and program marketing.

Respondents who were familiar with the IACBE substantially agreed that its outcomes-assessment-oriented approach to accreditation offers the most flexibili- ty. This perception was especially strong

among institutions with various types of nontraditional programs. Correspond- ingly, all respondents-except for those belonging to the AACSB-saw the AACSB as having the least flexibility in accreditation.

Our results indicate an apparent self- serving bias at work among our respondents: They rated the benefits of their own accrediting association high- er than the other associations’ benefits. The data from this study cannot help us

determine whether this bias demon- strates (a) the respondents’ post hoc rationalization or (b) their having selected the most appropriate accredit- ing association for their circumstances.

The relative uniformity of goals across programs, regardless of accrediting association affiliation, may indicate that the homogeneity of business deans’ perceptions extends across all accredited business programs. That goal consistency might also indicate common perceptions of the competi- tive landscape. Future research may be necessary to explore the reasons for homogeneous goals among business deans.

Reasons for Not Seeking Accreditation

Twenty-four percent of our respon- dents indicated that currently they were not seeking business accreditation. These institutions saw business accredi- tation as less important for ensuring program competitiveness and for ensur- ing the quality of student learning than did accredited institutions. In addition, these institutions rated every benefit of accreditation lower than the accredited institutions did. Yet, we found few dif- ferences in program goals. This finding indicates that the decision to seek accreditation is not caused by differ- ences in program goals but rather by the institution’s perception that accredita- tion will help its business school attain those goals.

A variety of individual reasons were given for not seeking accreditation. Some respondents mentioned the expense and effort involved in seeking and/or maintaining accreditation. Oth- ers reported having felt no pressure from stakeholders to become accredit- ed, either from prospective students or the institution’s administration. Others indicated that they would not be able to meet the standards either in terms of curriculum or faculty qualifications. Several reported that other issues, such as curriculum initiatives, program restructuring, and turnover, were con- suming their attention and left little time for business accreditation planning. And one respondent quite honestly reported that he or she was too overwhelmed by his or her current workload.

Conclusion

Business accreditation is a salient issue for many business schools. The

MarcWApril2003 203

[image:8.612.51.386.57.501.2]number of accredited business schools is rising and will probably continue to do so for some time. As a result, many more institutions may eventually seek business accreditation. For those institu- tions, the question becomes “when,” not “if.” Respondent comments seem to indicate that the time frame for seeking business program accreditation will be heavily influenced by competitive reali- ties in the market(s) in which each insti- tution competes.

Our study reveals several differences among respondents by accrediting asso- ciation. We found differences among AACSB, ACBSP, and IACBE institu- tions in perceived benefits, costs, flexi- bility, and reputation. Business schools considering specialized accreditation should examine not only the costs and benefits of accreditation, but also the advantages and disadvantages of each of the accrediting bodies. Each has its own philosophy and approach to accreditation. Given the variety of pro- grams-both traditional and nontradi- tional-reflected in this study, the dif- ferent ways in which these accrediting associations treat innovative and entre- preneurial organizational forms should be carefully examined.

We also recommend that institutions considering accreditation attempt to look toward the future to assess where each of the accrediting bodies will be 10 years from now. Which will have more member institutions? Which will have

more fully accredited programs? What will the composition of their member- ship look like? In the future, how will the goals of the accrediting association compare with the goals of the institu- tion? Business accreditation is a long- term commitment; therefore, schools should look down the road and assess

the future of the relationship.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

NOTES

1. We realize that business units may be struc- tured as departments, divisions, schools, or col- leges. For simplicity, we refer to the business unit as a “school of business” throughout this article, and to its leader as a “dean.”

2. One may argue that the market for profes- sional accreditation is evolving into distinct seg-

ments

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

or clusters, with each segment gravitatingtoward the accrediting body that best meets its unique strategic and operating challenges and priorities.

REFERENCES

Association of Collegiate Business Schools and

Programs (ACBSP). (1996).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Accreditationstandards f o r baccalaureate/graduate degree institutions. Overland Park, KS.

Bovee,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

S. L., Roller, R. H., & Andrews, B. K.(2000). The pursuit of excellence: Costs, bene- tits, and motivations for Christian college busi- ness accreditation. Research on Christian High-

er Education, 7, 45-69.

Cotton, C. C., McKenna, J. F., Van Auken, S., &

Yeider, R. A. (1993). Mission orientations and deans’ perceptions: Implications for the new AACSB accreditation standards. Journal of

Organizational Change Management,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

6( I),Hardin, J . R., & Stocks, M. H. (1995). The effect of AACSB accreditation on the recruitment of entry-level accountants. Issues in Accounting

Education,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

10(1), 83-90.Henninger, E. A. (1998a). Dean’s role in change: 17-27.

The case of professional accreditation reform of American collegiate business education. Jour-

nal of Higher Education Policy & Management,

20(2), 203-214.

Henninger, E. A. (1998b). The American Assem- bly of Collegiate Schools of Business under the new standards: Implications for changing facul- ty work. Journal of Education for Business,

Jantzen, R. H. (2000). AACSB mission-linked standards: Effects on the accreditation process.

Journal of Education f o r Business, 75(6),

Kemelgor, B. H., Johnson, S. D, & Srinivasan, S.

(2000). Forces driving organizational change: A business school perspective. Journal of Educa-

tion f o r Business, 75(3), 133-138.

Levernier, W., & Miles, M. P. (1992). Effects of AACSB accreditation on academic salaries.

Journal of Education f o r Business, 68( I ),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

55-6 1.

McKenna, J. F., Cotton, C. C., & Van Auken, S. (1995). Business school emphasis on teaching, research and service to industry: Does where you sit determine where you stand? Journal of

Organizational Change Management, 8(2),

MacKenzie, 0. (1964). Accreditation of account- ing curricula. The Accounting Review, 39(2), 363-370.

Pastore, Jr., J . M. (1989). Developing an academ- ic accreditation process relevant to the account-

ing profession. The CPA Journal,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

159(5),18-26.

Pearson, D. B. (1979). Will accreditation improve the quality of education? Journal of Accountan-

Posey, R. B., & Parker, H. J. (1989). Publication activity of AACSB accredited accounting pro- grams. The Accounting Educator’s Journal,

Srinivasan, S., Kemelgor, B., & Johnson, S. D.

(2000). The future of business school scholar- ship: An empirical assessment of the Boyer framework by US. deans. Journal of Education

f o r Business, 76(2), 75-8 I .

Stettler, H. F. (1965). Accreditation of collegiate accounting programs. The Accounting Review, 40(4), 723-730.

73(3), 133-137.

343-348.

3-16.

CY, 147(4), 53-58.

2(2), 32-38.

204 Journal