On: 10 January 2014, At: 08:56 Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Attachment & Human Development

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rahd20

Observational attachment theory-based

parenting measures predict children’s

attachment narratives independently

from social learning theory-based

measures

Carla Matiasa, Thomas G. O’Connorb, Annabel Futhc & Stephen Scottcd

a

Universidade Lusíada do Porto, Porto, Portugal b

Wynne Center for Family Research, University of Rochester Medical Centre, New York, NY, USA

c

King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK d

National Academy for Parenting Research, London, UK Published online: 28 Nov 2013.

To cite this article: Carla Matias, Thomas G. O’Connor, Annabel Futh & Stephen Scott , Attachment & Human Development (2013): Observational attachment theory-based parenting measures predict children’s attachment narratives independently from social learning theory-based measures, Attachment & Human Development, DOI: 10.1080/14616734.2013.851333

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.851333

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

D

ow

nl

oa

de

d by [Roya

l H

ol

low

ay, U

ni

ve

rs

it

y of L

ondon] a

t 08:

56 10 J

anua

Observational attachment theory-based parenting measures predict

children

’

s attachment narratives independently from social learning

theory-based measures

Carla Matiasa, Thomas G. O’Connorb, Annabel Futhcand Stephen Scottc,d*

a

Universidade Lusíada do Porto, Porto, Portugal;bWynne Center for Family Research, University of Rochester Medical Centre, New York, NY, USA;cKing’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry,

London, UK;dNational Academy for Parenting Research, London, UK

(Received 7 January 2013; accepted 13 June 2013)

Conceptually and methodologically distinct models exist for assessing quality of parent–child relationships, but few studies contrast competing models or assess their overlap in predicting developmental outcomes. Using observational methodology, the current study examined the distinctiveness of attachment theory-based and social learning theory-based measures of parenting in predicting two key measures of child adjustment: security of attachment narratives and social acceptance in peer nomina-tions. A total of 113 5–6-year-old children from ethnically diverse families partici-pated. Parent–child relationships were rated using standard paradigms. Measures derived from attachment theory included sensitive responding and mutuality; measures derived from social learning theory included positive attending, directives, and criti-cism. Child outcomes were independently-rated attachment narrative representations and peer nominations. Results indicated that Attachment theory-based and Social Learning theory-based measures were modestly correlated; nonetheless, parent–child mutuality predicted secure child attachment narratives independently of social learning theory-based measures; in contrast, criticism predicted peer-nominated fighting inde-pendently of attachment theory-based measures. In young children, there is some evidence that attachment theory-based measures may be particularly predictive of attachment narratives; however, no single model of measuring parent–child relation-ships is likely to best predict multiple developmental outcomes. Assessment in research and applied settings may benefit from integration of different theoretical and methodological paradigms.

Keywords: parent–child relationships; attachment; parenting; internal working models; peer nominations

Several conceptual models exist to explain the nature of parent–child relationships and the

mechanisms by which they influence children’s social and psychological development;

some models have formed the basis for clinical interventions. Leading models of parent–

child relationships have been developed and operationalized largely in isolation, often without cross-fertilization or systematic efforts to distinguish what is particular about each model or its attendant measures. As a result, and despite calls for integrative research on parenting across multiple models (Grusec, 2011), we do not yet have a strong evidence base to inform choices made in research studies or clinical settings about whether or not there are substantive distinctions between measures of parent–child relationship quality

derived from different theoretical models. The current study contributes to the limited comparative research by examining what may be particular to an attachment theory-based model of parent–child relationship quality as a predictor of a key attachment outcome,

attachment representation, and a more general index of social competence derived from peer nominations.

We focus on measures derived from attachment theory (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bowlby,1988), an influential model of the parent–child relationship with a

substantial research base and clinical application (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van, & Juffer, 2003), and social learning theory, an equally influential model with a substantial evidence base and clinical application (Dishion & Snyder,2004; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989; Webster-Stratton, Jamila Reid, & Stoolmiller,2008). We examine these two models (among many that could be considered) because they are derived from distinct theoretical traditions and have established observational methodologies.

A starting point for our investigation was to identify what may be distinctive about an attachment theory-based approach to parenting assessment. One candidate for child out-come is the internal working model or attachment representations, a psychological mechanism that underpins attachment theory, its assessment, and its clinical application (Bowlby,1982; Bretherton,2005; Steele, Steele, & Johansson, 2002). In infancy, secure internal working models are hypothesized to develop from sensitively responsive parental care. From the experience of parental sensitive care, the child develops a model of the attachment figure as available, protective, and caring, and of the self as worthy of love and protection. In contrast, children exposed to a pattern of unresponsive, insensitive care develop an insecure internal working model in which their models of others and self are unreliable, unlovable, and unprotective. The hypothesis that sensitively responsive care leads the child to construct a secure internal working model is central to attachment theory and is supported by many studies (e.g., De Wolff & van Ijzendoorn, 1997). However, empirical evidence that caregiving experiences are associated with an index of attachment quality from separation-reunion procedures or narrative assessments past infancy is limited (Dubois-Comtois, Cyr, & Moss, 2011; Stevenson-Hinde & Shouldice, 1995; Wong et al., 2011). That is in contrast to the comparatively large number of studies showing reliable associations between doll-play narrative assessments of internal working models and behavior problems in pre-school and school-aged children (e.g., Barone & Lionetti,2012; Bureau & Moss, 2010; Futh, O’Connor, Matias, Green, & Scott,2008).

Studies are needed to examine the connection between the quality of the “real-life”

experiences with the caregiver with the internal working model in school-aged children, both to extend this component of the attachment model past infancy and to examine this connection amidst developmental changes in the child and the dyad. In particular, as compared with infants, the association between parental sensitivity and children’s internal

working model may differ in school-aged children. That is suggested from developmental changes in the child’s affective expression that may elicit caregiving (e.g., Mesman, Oster,

& Camras,2012); additionally, models of sensitivity that underlie the parent’s ability to

act as a safe haven for a distressed child and secure base for exploration have not been routinely applied past infancy. One developmental change that has been articulated is the

“goal-corrected partnership”(Bowlby,1982; Marvin & Britner,2008), or the notion that

the child and parent are increasingly able to operate toward a shared set of negotiated goals. That is, experiences of a mutual partnership may also (i.e., in addition to sensitive-responsive parental care) lead to and correspond with the formation of secure internal models in the school-aged child. Several studies have examined problem-solving interac-tions in relation to adolescent attachment (Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, &

Gamble,1993; Obsuth, Hennighausen, Brumariu, & Lyons-Ruth,2013; Scott, Briskman, Woolgar, Humayun, & O’Connor,2011); we assess mutual or goal-corrected behavior in

several settings in relation to secure internal models in young school-aged children. Equally importantly, the study aimed to examine if observational measures derived from an alternative model of parent–child relationships, social learning theory, were as

effective at predicting children’s attachment narratives. That is, we wished to discover

whether or not observational parenting measures derived from social learning theory would predict the quality of attachment narratives as effectively as measures derived from an attachment theory tradition. This hypothesis has not yet been tested, but may hold important conceptual, methodological, and clinical applications. There is a solid basis for proposing that social learning theory-based parenting measures would equally predict children’s attachment narratives. Most fundamentally, social learning theory proposes that

parenting qualities are learned or internalized to shape children’s social-cognitive

pro-cesses such as attributional biases; these social-cognitive propro-cesses, in turn, mediate social and behavioral outcomes (Crick, Grotpeter, & Bigbee, 2002; Dodge, Pettit, Bates, & Valente,1995).

On the other hand, there are important differences between these models in how the parent–child relationship is conceptualized and measured through observational research.

Specifically, whereas attachment theory focuses on sensitive responding to the child’s

needs, social learning theory models emphasize different parenting dimensions, including (1) positive attention and praise as reinforcers of positive child behavior; (2) clear directions and consequences contingent on undesirable behavior; and (3) criticism con-tributing to coercive cycles that engender antisocial behavior through evoking increas-ingly hostile responses in an interactional build-up (Patterson, 1982). Of course, even though these parenting measures differ from those proposed by attachment theory, they might still predict security of children’s attachment narratives. Accordingly, we examined

if measures that operationalize attachment theory and social learning theory models were equally predictive of children’s attachment narratives.

A second index of social and emotional development to be predicted from observa-tional parenting measures is the ability to make harmonious relationships with other children. We focus here on peer competence indexed by peer nominations, a leading measure of the construct. Both attachment theory and social learning theory predict a link between parenting and peer relations. Children’s experiences of sensitivity and the mutual

quality of the goal-corrected partnership with their attachment figures are proposed to be carried forward into other relationships, accounting for within-individual stability in relationship patterns (Sroufe,2005); empirical evidence links parental sensitive respond-ing or attachment security to competence with peers (Sroufe, 2005; Thompson,2008). Similarly, social learning theory proposes parent–child relationship mechanisms that lead

to good peer relations, with the child being rewarded for prosocial overtures and dis-ciplined for antisocial acts. Empirical research in this tradition provides considerable evidence that positive parenting and disciplinary practices as measured from a social learning standpoint predict peer pro-social behavior and social competence (Sandstrom & Coie,1999); in contrast, harsh parenting is linked with antisocial behavior, peer rejection, and social-skills deficits (Patterson, Dishion, & Yoerger,2000).

Whether or not these alternative models–with their particular hypothesized

mechan-isms and assessed dimensions of parenting – differentially predict peer competence has

received markedly little attention, and relevant research provides mixed results. Fagot’s

(1997) findings indicated that attachment classification did not provide additional infor-mation to negative parenting behavior when predicting peer negative reciprocity in the

playgroup; however, Rose-Krasnor (1996) found that attachment security was associated with positive social engagement in group play whereas maternal directiveness was associated with aspects of children’s problem-solving behavior. The current study seeks

to expand this line of inquiry by examining the overlap and distinctiveness of the measures of the two different models for predicting peer nominations of social competence.

It is important to distinguish between a theory and its operationalization in practice. This study made use of measuring approaches that, for each model, are widely used. For attachment related constructs, global scales were used to assess the key dimensions of sensitivity and mutuality, as an index of the goal-corrected partnership. Attachment-based dimensions were rated during everyday tasks (i.e., not paradigms particular to attachment theory), although there is ample evidence that attachment-related caregiving is observable outside of attachment paradigms such as separation-reunion situations (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Pederson & Moran, 1996). For social learning theory-related constructs, event counts of parental behaviors during the interaction with the child were used, the dominant approach taken in the last three decades (Dishion & Snyder,2004; Patterson,1982). We focused on contingent responses to child behavior as well as general behavior (e.g., criticism) of the parent. That is, each set of measures used to index attachment and social learning theory in the current study were derived or adapted from existing measures that offer a reasonable representation of their underlying theories.

In summary, our goal was to examine the extent to which widely-used, good quality observational measures derived from attachment and social learning theory overlapped, and whether they differentially predicted two independently-rated key outcomes in young school-aged children, one particular to attachment theory, attachment narratives, and one that is more general, peer-nominated social competence.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The study is based on the first (pre-treatment) wave of data from the Primary Age Learning Skills (PALS) study, a preventive parenting intervention for at-risk, inner-city families (Scott et al., 2010). The study took place in four primary schools in the most disadvantaged ward in one of the most deprived inner-city London boroughs. Only children from the second and third cohorts were involved because the attachment narrative measure was not included in the first cohort. The primary caregiver of 151 children (n= 70 higher risk,n= 81 lower risk) were approached and 75% agreed to take part and were available for data collection (n =51 higher risk,n =62 lower risk). A total of 47% of mothers were Black African (first generation immigrants), 20% were of African Caribbean origin, 20% White British/European, and 11% “Other”. Children’s mean age

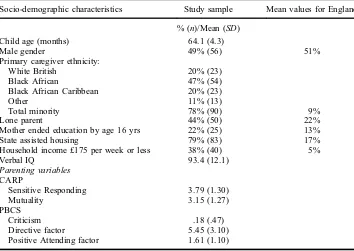

was 5 years 4 months; 49% were male (Table 1). Written consent was obtained from each participant; the local research ethics committee approved the study.

Observational data were gathered in the home by videotaping the child with his/her primary caregiver (the vast majority, 86%, of primary caregivers were mothers). Three standard observational tasks were used (O’Connor, Matias, Futh, Tantam, & Scott,2013):

(a) free-play with a designated set of toys (10 minutes), (b) structured-play task where the parent and child worked collaboratively to recreate a pictured Lego structure (10 minutes); (c) tidy-up task (3 minutes). The latter two scenarios create moderate distress due to the difficulty in accurately assembling the Lego structure, and the time-pressure imposed in

the tidy-up. Coders underwent extensive training in the two rating systems described below. Given the limited number of coders available, the same coder used each coding system to rate a particular dyad, but the ratings were conducted at least 4 weeks apart and coders were blind to outcome measures. In the 30 cases that were double coded for reliability purposes, the degree of overlap between measuring approaches was similar when coded by the same or the separate coder, suggesting the two approaches were not conflated when both were rated by one coder. Attachment narrative data and peer nominations were gathered in the school and coded independently of parent–child

inter-actions by different researchers; demographic data were collected at the home visit along with the observational data.

Measures

TheCoding of Attachment-Related Parenting (CARP) (Bisceglia et al.,2012; O’Connor

et al.,2013) is a global measure of parent–child interaction quality that was derived from

attachment theory and related assessments in young school-aged children (Kochanska & Murray, 2000; Stevenson-Hinde & Shouldice, 1995). The CARP places conceptual emphasis on patterns of sensitivity, emotional attunement, and bi-directional dyadic processes such as mutuality. Two attachment-related parenting behaviors are the focus of this study; each uses a 7-point Likert scale (1 = No evidence; 7 = Pervasive/extreme evidence).Sensitive Respondingassesses the degree to which the parent shows awareness of the child’s needs and sensitivity to his/her signals, promotes the child’s autonomy, Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Socio-demographic characteristics Study sample Mean values for England

% (n)/Mean (SD)

Mother ended education by age 16 yrs 22% (25) 13%

State assisted housing 79% (83) 17%

Household income £175 per week or less 38% (40) 5%

Verbal IQ 93.4 (12.1)

adopts the child’s psychological point of view, and physically or verbally expresses

positive emotion and warmth towards the child. Mutuality is conceptually compatible with the notion of the“goal-corrected partnership”(Bowlby,1982) and reflects the degree

to which parent and child in the dyad accept and seeks the other’s involvement in a joint

activity, build on each other’s input and coordinate their efforts/actions while conducting a

task together, maintain shared attention and fluid conversation, reciprocate positive affec-tionate behaviors, and keep physical proximity/closeness when interacting with each other. Means (SD) of the two CARP scales are provided inTable 1. Inter-rater reliability of 30 parent–child play observations coded by two independent raters was good; intraclass

correlations (ICC) were .73 for Sensitivity and .81 for Mutuality. Evidence for the validity of measure is found in a recent treatment study showing change in response to parental intervention (O’Connor et al.,2013).

TheParent Behavior Coding Scheme(PBCS) is an event-based observational measure deriving from existing social learning observational measures adapted from the widely used Behavior Coding Scheme (BCS) (Forehand & McMahon,1981). Conceptually, the PBCS categories heavily draw on the association between specific disciplinary parenting practices and problem behavior in children (Dishion & Snyder,2004; Webster-Stratton et al.,2008). The measure assesses contingent maternal utterances. Child-centered verbalizations include descriptive commenting of the child’s actions, positive and facilitative remarks about his/her

achievements, and praising the child’s behavior. Child-directive verbalizations include

parental commands and prohibitions. Critical verbalizations have both negative content and negative tone. Principal components analysis of the scales and prior research and conceptual models led us to derive three factors for analysis (details from last author) which we refer to as Positive Attending (identified by five scales: attending, positive attending, praise, seeking cooperation, facilitating), Directive parenting (indicated by three scales: vague commands, clear commands, and prohibitions) and Criticism. Means (SD) for the PBCS Criticism scale and Directive and Positive Attending factors are presented inTable 1; these descriptive data are presented for illustrative reasons; we use standardized scores in analyses. Whereas Positive Attending and Directive parenting are contingent parenting behaviors (i.e., coded in response to child behavior and the interac-tion), Criticism may be contingent or non-contingent (i.e., global critical comments). The median intraclass correlation across codes, based on a set of 30 tapes, was .75.

The Manchester Child Attachment Story Task (MCAST) (Green, Stanley, Smith, & Goldwyn, 2000) is a narrative story stem task to elicit attachment representations in school-age children (Colle & Del Giudice, 2011; Futh et al., 2008) . Using dyadic play scenarios with a target child doll, mother doll, and dollhouse, the child’s attachment

representations are evaluated from doll characters’behavior and the organization, content,

and coherence of the child’s narrative to four story-stems (nightmare, hurt knee, feeling ill,

lost in a store). Emotional mood induction is used to generate mild stress and increase the likelihood of evoking attachment feelings and cognitions. The interview is videotaped for later coding. The MCAST was administered at school to avoid possible bias from having the caregiver in the immediate vicinity. Content codes (rated using a 9-point scale unless otherwise noted) were: Maternal Responsiveness, Warmth, Assuagement evident in the child’s narrative and by observation, Affect modulation (6-point scale), and Mentalizing

(of self and mother, which were combined; rated 0–3). The scales were standardized

through Z-scores. Attachment Disorganization was coded as any evidence of bizarre, unusual features in the child’s narrative using a 9-point scale. Factor analyses (details

available from the authors) supported the compositing of the content codes to form a continuous scale of attachment security; for a priori reasons, the Disorganization scale

was considered separately. Reliability was demonstrated in two phases. First, the main attachment coder, who was blind to all identifying information and observational ratings, passed a reliability assessment for continuous and categorical codes on an independent sample of 10 cases as part of the MCAST training (80% agreement for classifications). Second, on 20 randomly selected tapes from the current sample, ICCs across the scales averaged .67 and there was 80% agreement on the 4-way classification (kappa = .66,

p < .01). We use a continuous scale of attachment security because of the statistical advantages over categorical ratings.

Peer nominations

This is a well-validated method of measuring social adjustment (Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Gremaud, & Bierman,2002). Three attributes were obtained: peer-rated popu-larity (“like most”), peer rejection (“like least”), and fighting behavior (“fights”). The

standard peer nomination methodology was used, whereby each child in the classroom is asked to nominate three children for “like most”, “like least”, and “fights” categories;

children made selections while viewing a school photograph of their classmates. Scores were standardized within class to allow comparisons across classes. All peer nomination ratings were made privately at school. Because the principal in one school was unwilling to allow peer nominations, fewer children had data on this measure.

TheBritish Picture Vocabulary Test(Dunn & Dunn,1981) is a standardized measure of child verbal intelligence, adapted from the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Testers were trained by a professional authorized by the test developer and certified as competent to administer the test.

Socio-demographic factors

We measured parental education (categorized as low = left school by 16 yrs; mid = secondary/technical qualification; high = degree), income (categorized as low = <£175 p/week; mid = £176 to £325 p/week; and high = >£326 p/week), single-parent status, and housing type (categorized as council house/flat and owned/ rented property); and self-designated ethnicity of the parent (see Table 1).

Results

The MCAST measures of Security and Disorganization were moderately negatively correlated (r(110) =–.57,p< .01) and both were correlated with verbal IQ (r(112) = .26,

p< .01;r(109) =–.22,p< .05, respectively). Females were rated more secure than males

(standardized means across the scales were .12 (.77) for females and–.27 (.86) for males,

t(111) = 2.53, p < .05). Gender and verbal intelligence were therefore included as covariates when predicting attachment security. The only socio-demographic variable associated with Peer nominations was gender; compared to females, males received more nominations for Dislike (3.27 (2.52) vs 2.12 (1.93), t(100) = –2.61, p < .05) and

Fights (5.29 (4.07) vs 1.14 (1.18),t(100) =–7.00,p< .01). Gender was therefore included

as a covariate when predicting peer status.

D

ow

nl

oa

de

d by [Roya

l H

ol

low

ay, U

ni

ve

rs

it

y of L

ondon] a

t 08:

56 10 J

anua

Overlap between attachment and social learning theory measures

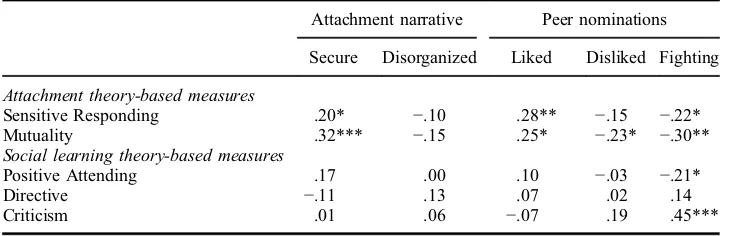

Correlations between parenting measureswithineach theory indicated substantial overlap between Mutuality and Sensitive Responding (Table 2). Within the social learning measures, there was modest overlap between Positive Attending and Directive Parenting; Criticism was unrelated to Positive Attending but modestly associated with Directive Parenting (Table 2). Correlations between measures from each theory indicated the highest degree of overlap for positive parenting measures but no relationship between attachment measures and Directive Parenting, and a modest negative relationship between the two attachment measures and Criticism (Table 2). It therefore appears that the measures of positive parenting from either theory may be tapping into somewhat similar processes, whereas the social learning theory-derived measures of Directive Parenting and Criticism are indexing processes that are distinct from the attachment theory-derived measures.

Prediction of child social adjustment from parenting measures

There were modest to moderate correlations between the two attachment-based measures of parenting and attachment security and peer nominations (Table 3). In contrast, none of the social learning theory measures was significantly associated with the attachment narrative measures; however, both Positive Attending and Criticism were associated with peer nominations of fighting. Also, as the findings in Table 3show, none of the attachment theory-based or social learning theory-based measures of parenting was sig-nificantly associated with Disorganization in the attachment narrative.

Table 2. Correlations between attachment theory-based and social-learning theory-based parenting measures.

Positive Attending Directive Criticism Sensitive Responding

Directive .20*

Table 3. Correlations between parenting measures and child outcomes.

Attachment narrative Peer nominations

Positive Attending .17 .00 .10 −.03 −.21*

Regression analyses were used to examine the uniqueness of the different approaches to parenting measurement. Given the high degree of overlap between Mutuality and Sensitive Responding, we focus on the former in analyses below (the pattern of results with Sensitive Responding was similar; details available from the authors).

Regression analyses were performed to test the hypothesis that Mutuality was significantly associated with secure attachment narratives independent of socio-demographic variables and three parenting measures from the social learning theory model: Positive Attending, Directive Parenting and Criticism. Although the bivariate associations between social learning theory-based measures and attachment narrative were not significant, we nevertheless wanted to ensure that they did not mediate the prediction from the attachment based Mutuality measure. As might be expected from the pattern of correlations in Table 3, regression results indicated that observed Mutuality was significantly associated with secure attachment narrative independent of all covariates (B = .16; SE = .07;t= 2.34, p< .05); of the other variables in the model, only child gender (B = –.36; SE = .15; t = –2.36, p < .05), and verbal IQ (B = .02;

SE = .01;t = 2.47,p< .05) were also significantly associated with attachment security. Peer nominations of fighting were significantly associated with both attachment and social learning theory measures in bivariate analyses; accordingly, we conducted a regression analyses with both sets of parenting measures as predictors. Regression results (Table 4) indicated that attachment-based ratings did not predict significant independent variance in peer nominations whereas the social learning theory construct of Criticism did; male gender was also a significant predictor. Regression models for peer nominations of Liked and Disliked indicated that neither attachment nor social learning theory measures predicted peer ratings independently, despite the significant bivariate correlations reported inTable 3; this implies that the attachment theory-based and social learning theory-based measures account for overlapping variance.

Given the ethnically diverse nature of the sample, we carried out a series of supple-mentary analyses to examine possible moderator effects by ethnicity or social class

Table 4. Prediction of peer nominations from parenting scales.

Like Dislike Fighting

Notes: Regression estimates reported from the final model. *p< .05; ***p< .001.

indicators. We found no reliable evidence that any of the demographic factors inTable 1 moderated the associations between parenting/attachment measures and child outcomes (details available from the last author).

Discussion

It might be presumed that, because of their different conceptual origins, parent–child

measures derived from attachment and social learning theories would not overlap and would differentially predict developmental outcomes. This important hypothesis has received surprisingly little clinical or empirical attention, however. As a result, rather than ascribing particular significance to one model or another, the contrary position might also be proposed: that is, there is substantial overlap between and predictive power from alternative parent–child measures because the core elements of“good quality”parenting

are equally detected by measures derived from different theories.

We did not set out to provide a definitive test of the distinctiveness of attachment theory-and social learning theory-based measures of parenting. Instead, we aimed to begin to fill in the gap in research that translated different conceptual models into practical measures for research and practice. The current study yielded two particularly novel findings. The first is that observer ratings of parent–child interaction quality during

standard interaction tasks predicted the quality of children’s attachment narratives in

young school-aged children. A second related, and more novel, finding is that observa-tional measures of parent–child interaction quality predicted children’s attachment

narra-tives independent of observational measures derived from an alternative model, social learning theory. Somewhat less novel but notable is the finding that peer nominations were associated with multiple measures of parent–child relationship quality; peer-reported

fighting behavior was particularly associated with critical parenting behavior. We discuss the implications of the findings after noting the study strengths and weaknesses.

There were a number of limitations. First, given the inclusion of high-risk, ethnically diverse families, these findings may not generalize to other samples – although the

findings might be expected to generalize to high-risk samples in general, which tend to be ethnically diverse. We found no evidence for moderation by ethnicity, but the study was not powered to test ethnicity as a moderator. We also focused on a single caregiver, which is inevitable given the high rate of single-parent families in moderate-high risk settings. Also, it is possible that recording parenting behavior under more stressful situations such as when the child is worried, ill or unexpectedly separated would have led to stronger associations with child narratives. Furthermore, whereas attachment theory measures were coded on global scales, social learning theory measures were based on event sampling. Differences between measures and their predictions might reflect this different coding strategy. However, this difference is consistent with how measures are conventionally coded within each model, and the data presented here suggest that related constructs can be highly correlated despite different coding strategies. Given the practical limits and demands of coding, the same rater coded all parenting measures (in separate coding sessions); shared rater variance between attachment theory-based and social learning theory-based measures would bias against finding distinct predictions. Finally, given the cross-sectional nature of the design, we cannot draw casual conclusions about direction of effects. Counter-balancing these limitations were several strengths to this study, including a reasonably large sample for intensive, direct observational methodol-ogy; the inclusion of hard-to-reach families that are often not well-represented in research; high quality direct observational measures of parent–child interaction assessed from

alternative conceptual-methodological schemes; and outcome measures that were derived from independent sources using very distinct methodologies.

An important finding in this study was the link between observer ratings of parent–

child interaction quality during standard assessment procedures and the quality of school-aged children’s attachment narratives derived from the story-stem methodology. That is an

important complement to existing research on attachment narratives in school-aged children, which has tended to focus on adjustment outcomes. Indeed, empirical evidence linking observational measures of caregiver behavior to attachment security is substantial in infancy (Belsky, 1999; NICHD & E. C. C. R. N, 2006); but limited past infancy (Stevenson-Hinde & Shouldice, 1995). The observational coding system used in the current study was designed specifically to build on the work in younger children, and provides some of the only observational evidence in school-aged children that caregiver sensitivity and a mutually responsive interaction pattern predict how children talk about attachment experiences using the very distinct methodology of the narrative assessment (and coded by independent raters). Furthermore, this study found that there is something unique about the ability of observational ratings of parenting derived from an attachment theory model to predict attachment narratives. Specifically, Mutuality, the manner in which caregivers and children negotiate play, tasks, and clean-up – and analogous to

the goal-corrected partnership notion from attachment theory–predicted narrative

attach-ment security after accounting for alternative observational measures and covariates; analyses of the Sensitive Responding construct were parallel but somewhat weaker. In contrast, measures of positive attention derived from a social learning model (Patrick, Snyder, & Schrepferman, 2005) were weakly and non-significantly associated with attachment narratives. The implication is that there may be value in operationalizing caregiving behaviors along the lines developed by attachment theory rather than using a more general “positive” style of interacting for understanding the security/insecurity of

children’s attachment narratives. In addition to contributing to the validity of the

observa-tional and narrative measures, these findings also support the value of ascertaining attachment-related parenting in naturalistic observational situations rather than only in separation-reunion procedures (Pederson & Moran, 1996). The distinctive benefit of attachment theory-based parenting measures were limited to attachment-specific out-comes, attachment representations, and not to another key index of social and emotional development, peer nominations.

We did not find reliable links between either attachment or social learning measures of parent–child interaction quality and attachment Disorganization in the story stem

narra-tive. That may be because parenting behaviors associated with disorganization are less likely to be observed in brief observations in everyday settings, or because the observa-tional ratings did not include relevant dimensions. Adding dimensions such as parental helpless states of mind, abusive or fear-inducing behavior (Lyons-Ruth, Yellin, Melnick, & Atwood,2005), and various ways in which maternal awareness of infant states has been coded (Fonagy & Target,2005; Meins, Fernyhough, Fradley, & Tuckey,2001) may have improved prediction of disorganization. It is possible that attachment disorganization was not adequately assessed in the narrative measure, although that explanation is challenged by previous analyses linking this measure of disorganization to behavioral and emotional problems (Futh et al.,2008).

Both attachment and social learning theory hypothesize that parent–child relationship

quality would predict peer competence, although perhaps from different parenting dimen-sions and/or through different mechanisms. Results from this investigation indicated that measures from both models predicted peer nominations of aggression (fighting).

However, social learning theory based ratings of parent–child interaction (criticism) added

additional prediction of peer nominated fighting behavior independent of attachment-based ratings, which did not predict unique variance. That is similar to Fagot’s (1997)

findings, and suggests that there may be a particular value in assessing conflict and criticism specifically when predicting negative child behavior that is carried forward to other settings and relationships, perhaps because of a direct behavioral learning (e.g., modeling) process. Critical and coercive parenting, which were directly captured in the social learning based measures (and arguably less so in the attachment theory-based measures), provides the means and the opportunity to teach a child a repertoire of aversive and aggressive behaviors. It may be noteworthy that none of the parenting measures predicted unique variance in the other dimensions of peer ratings. It is possible that the associations with Fighting were stronger than for measures of acceptance/rejection because it is a more readily observable outcome to young children or because it has greater salience in this high-risk setting. It is also important to note that conceptions of

“like” and “dislike” or popularity may be confounded in high-risk settings because of

social norms that may reward disruptive behavior.

There are obvious challenges in contrasting attachment and social learning theory models of the parent–child relationship for predicting social competence in school-aged

children. For example, there is similarity in how attachment theory-based and social learning theory-based measures are described, and some studies have begun to integrate concepts from attachment and social learning theory models directly (Kerns, Tomich, Aspelmeier, & Contreras, 2000; Scott et al.,2011; Sutton,2001; Van Zeijl et al.,2006). Nevertheless, uncertainty about which models or measures to adopt for practical use in a research or clinical setting remains a common problem because of the general lack of comparative research. The broader goal of this line of study is to test and clarify the limits of distinct models and the reliability of their translation toward the formation of an integrative model and measurement (Grusec, 2011). One specific challenge for research combining measures from alternative models is methodological. For example, whereas attachment studies have tended to focus on global measures, social learning theory measures tend to focus on discrete behaviors (Forehand & McMahon, 1981; Patterson, 1982). That difference in methodology – molar versus molecular coding – creates an

inevitable confound in comparing measures, and that may have influenced the results. However, the difference between frequency counts and rating scales should not be over-emphasized, as the correlation between the frequency of positive attending counts and sensitive responding rating was high. Our focus was in contrasting alternative modelsas they are typically appliedbecause this would offer the most relevant test of our hypoth-eses. Clearly, further progress in testing, contrasting, and integrating alternative models of parent–child relationship quality will also depend on methodological refinements, which

currently vary across conceptual traditions. Linking this kind of work to clinical contexts is particularly needed given concerns–and so far, limited data–on how well traditional

research measures inform decision-making about parenting and intervention in such settings as custody and visitation, foster care, and pediatric clinics (Byrne, O’Connor,

Marvin, & Whelan,2005; Joseph, O’Connor, Briskman, Maughan, & Scott, 2013;

Marie-Mitchell & O’Connor,2013).

Comparing alternative observational ratings scales is rarely executed in developmental research (Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Connor, 1994; McElhaney & Allen, 2001), but

provides a particularly strong test of alternative models. This strategy may be especially valuable to address calls to consider how attachment, social learning, and other models of parent–child relationship are distinct or redundant (Goldberg, Grusec, & Jenkins, 1999;

O’Connor,2002). Observational assessments are intensive and therefore expensive, but

are considered a gold standard for elucidating causal mechanisms and determining the effectiveness of clinical treatment. A key consideration is which conceptual model and set of associated observational measures may be most suited to the conceptual or clinical question of interest; these findings begin to address that issue. Lastly, our findings underscore the potential value in adopting a cross-theoretical, integrative approach to assessment for academic studies and applied settings. For example, young children exhibiting aggression towards their caregiver may be seen by some practitioners as suffering from an insecure attachment pattern and could be offered attachment-based psychotherapy (Speltz, DeKlyen, & Greenberg,1999); other practitioners might interpret oppositional behavior as a consequence of reinforcement of antisocial acts and offer parent training . Whether both approaches are effective and, if so, whether or not it is due to the same mechanism requires additional clinical research. Findings from these kinds of investigations could inform practitioners about how and when to apply different models to treatment, such as when one approach is not working (Scott & Dadds,2009), and help identify potential sources of variation in response to parenting interventions (Scott & O’Connor,2012).

Funding

This research was made possible by grants from the Foundation for Science and Technology – Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education, Lisbon, Portugal, the Joseph Rowntree Trust, the Psychiatry Research Trust, the Jacobs Foundation, and the Economic and Social Research Council (UK).

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Allen, J. P., Hauser, S. T., Bell, K. L., & O’Connor, T. G. (1994). Longitudinal assessment of autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of adolescent ego development and self-esteem.Child Development, 65(1),179–194.

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van, IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood.Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195–215.

Barone, L., & Lionetti, F. (2012). Attachment and social competence: A study using MCAST in low-risk Italian preschoolers.Attachment & Human Development, 14(4), 391–403.

Belsky, J. (1999). Interactional and contextual determinants of attachment security. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.),The handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 249–264). New York, NY: Guilford.

Bisceglia, R., Jenkins, J. M., Wigg, K. G., O’Connor, T. G., Moran, G., & Barr, C. L. (2012). Arginine vasopressin 1a receptor gene and maternal behavior: Evidence of association and moderation.Genes, Brain, and Behavior, 11(3), 262–268.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss, volume 1: Attachment(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). Developmental psychiatry comes of age.The American Journal of Psychiatry, 145(1), 1–10.

Bretherton, I. (2005). In pursuit of the internal working model construct and its relevance to attachment relationships. In K. G. K. E. Grossmann & E. Waters (Eds.), Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies (pp. 13–47). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bureau, J. F., & Moss, E. (2010). Behavioural precursors of attachment representations in middle childhood and links with child social adaptation. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28(Pt 3), 657–677.

Byrne, J. G., O’Connor T. G., Marvin, R. S., & Whelan, W. F. (2005). Practitioner review: The contribution of attachment theory to child custody assessments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(2), 115–127.

Colle, L., & Del Giudice, M. (2011). Patterns of attachment and emotional competence in middle childhood.Social Development, 20(1), 51–72.

Crick, N. R., Grotpeter, J. K., & Bigbee, M. A. (2002). Relationally and physically aggressive children’s intent attributions and feelings of distress for relational and instrumental peer provocations.Child Development, 73(4), 1134–1142.

De Wolff, M. S., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (1997). Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment.Child Development, 68(4),571–591.

Dishion, T. J., & Snyder, J. (2004). An introduction to the special issue on advances in process and dynamic system analysis of social interaction and the development of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(6), 575–578.

Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & Valente, E. (1995). Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(4), 632–643.

Dubois-Comtois, K., Cyr, C., & Moss, E. (2011). Attachment behavior and mother-child conversa-tions as predictors of attachment representaconversa-tions in middle childhood: A longitudinal study. Attachment & Human Development, 13(4), 335–357.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1981).Peabody picture vocabulary test-revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Fagot, B. I. (1997). Attachment, parenting, and peer interactions of toddler children.Developmental Psychology, 33(3), 489–499.

Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (2005). Bridging the transmission gap: An end to an important mystery of attachment research?Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 333–343.

Forehand, R. L., & McMahon, R. J. (1981).Helping the non-compliant child: A clinician’s guide to parent training. New York, NY: Guilford.

Futh, A., O’Connor, T. G., Matias, C., Green, J., & Scott, S. (2008). Attachment narratives and behavioral and emotional symptoms in an ethnically diverse, at-risk sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(6), 709–718.

Goldberg, S., Grusec, J., & Jenkins, J. (1999). Confidence in protection: Arguments for a narrow definition of attachment.Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 475–483.

Green, J., Stanley, C., Smith, V., & Goldwyn, R. (2000). A new method of evaluating attachment representations in young school-age children: The Manchester Child Attachment Story Task. Attachment & Human Development, 2(1), 48–70.

Grusec, J. E. (2011). Socialization processes in the family: Social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 243–269.

Joseph, M. A., O’Connor, T. G., Briskman, J. A., Maughan, B., & Scott, S. (2013). The formation of secure new attachments by children who were maltreated: An observational study of adolescents in foster care.Development and Psychopathology. doi:10.1017/SO954579413000540

Kerns, K. A., Tomich, P. L., Aspelmeier, J. E., & Contreras, J. M. (2000). Attachment-based assessments of parent-child relationships in middle childhood. Developmental Psychology, 36(5),614–626.

Kobak, R. R., Cole, H. E., Ferenz-Gillies, R., Fleming, W. S., & Gamble, W. (1993). Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem solving: A control theory analysis.Child Development, 64(1), 231–245.

Kochanska, G., & Murray, K. T. (2000). Mother-child mutually responsive orientation and con-science development: From toddler to early school age.Child Development, 71(2), 417–431. Lyons-Ruth, K., Yellin, C., Melnick, S., & Atwood, G. (2005). Expanding the concept of unresolved

mental states: Hostile/helpless states of mind on the Adult Attachment Interview are associated with disrupted mother-infant communication and infant disorganization. Development and Psychopathology, 17(1), 1–23.

Marie-Mitchell, A., & O’Connor, T. G. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences: Translating knowl-edge into identification of children at risk for poor outcomes.Academic Pediatrics, 13(1), 14– 19.

Marvin, R. S., & Britner, P. A. (2008). Normative development: The ontogeny of attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications (pp. 269–294). New York, NY: Guilford.

McElhaney, K. B., & Allen, J. P. (2001). Autonomy and adolescent social functioning: The moderating effect of risk.Child Development, 72(1),220–235.

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Fradley, E., & Tuckey, M. (2001). Rethinking maternal sensitivity: Mothers’comments on infants’mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 42(5), 637–648. Mesman, J., Oster, H., & Camras, L. (2012). Parental sensitivity to infant distress: What do discrete

negative emotions have to do with it?Attachment & Human Development, 14(4), 337–348. Miller-Johnson, S., Coie, J. D., Maumary-Gremaud, A., & Bierman, K. (2002). Peer rejection and

aggression and early starter models of conduct disorder.Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(3), 217–230.

NICHD, & E. C. C. R. N. (2006). Infant-mother attachment classification: Risk and protection in relation to changing maternal caregiving quality.Developmental Psychology, 42(1), 38–58. Obsuth, I., Hennighausen, K., Brumariu, L. E., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2013). Disorganized behavior in

adolescent-parent interaction: Relations to attachment state of mind, partner abuse, and psycho-pathology.Child Development. doi:10.1111/cdev.12113

O’Connor, T. G. (2002). Annotation: The“effects”of parenting reconsidered: Findings, challenges, and applications.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(5), 555–572.

O’Connor, T. G., Matias, C., Futh, A., Tantam, G., & Scott, S. (2013). Social learning theory parenting intervention promotes attachment-based caregiving in young children: Randomized clinical trial.Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 42(3), 358–370.

Office of National Statistics. (2000).Social trends. London: Author.

Patrick, M. R., Snyder, J., & Schrepferman, L. M. (2005). The joint contribution of early parental warmth, communication and tracking, and early child conduct problems on monitoring in late childhood.Child Development, 76(5),999–1014.

Patterson, G. R. (1982).Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior.The American Psychologist, 44(2), 329–335.

Patterson, G. R., Dishion, T. J., & Yoerger, K. (2000). Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro- and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 1(1), 3–13.

Pederson, D. R., & Moran, G. (1996). Expressions of the attachment relationship outside of the strange situation.Child Development, 67(3), 915–927.

Rose-Krasnor, L. (1996). The relation of maternal directiveness and child attachment security to social competence in preschoolers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 19, 309–326.

Sandstrom, M. J., & Coie, J. D. (1999). A developmental perspective on peer rejection: Mechanisms of stability and change.Child Development, 70(4), 955–966.

Scott, S., Briskman, J., Woolgar, M., Humayun, S., & O’Connor, T. G. (2011). Attachment in adolescence: Overlap with parenting and unique prediction of behavioural adjustment.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52(10), 1052–1062.

Scott, S., & Dadds, M. R. (2009). Practitioner review: When parent training doesn’t work: Theory-driven clinical strategies.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 50(12), 1441–1450.

Scott, S., & O’Connor, T. G. (2012). An experimental test of differential susceptibility to parenting among emotionally-dysregulated children in a randomized controlled trial for oppositional behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 53(11), 1184–1193.

Scott, S., O’Connor, T. G., Futh, A., Matias, C., Price, J., & Doolan, M. (2010). Impact of a parenting program in a high-risk, multi-ethnic community: The PALS trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(12), 1331–1341.

Speltz, M. L., DeKlyen, M., & Greenberg, M. T. (1999). Attachment in boys with early onset conduct problems.Development and Psychopathology, 11(2), 269–285.

Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood.Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349–367.

Steele, M., Steele, H., & Johansson, M. (2002). Maternal predictors of children’s social cognition: An attachment perspective.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 43(7), 861–872.

Stevenson-Hinde, J., & Shouldice, A. (1995). Maternal interactions and self-reports related to attachment classifications at 4.5 years.Child Development, 66, 583–596.

Sutton, C. (2001). Resurgence of attachment (behaviors) within a cognitive-behavioral intervention: Evidence from research.Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29, 357–366.

Thompson, R. A. (2008). Early attachment and later development: Familiar questions, new answers. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.),The handbook of attachment: Theory, research and clinical applications(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Van Zeijl, J., Mesman, J., Van, IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Juffer, F., Stolk, M. N.,…Alink, L. R. (2006). Attachment-based intervention for enhancing sensitive discipline in mothers of 1- to 3-year-old children at risk for externalizing behavior problems: A rando-mized controlled trial.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 994–1005. Webster-Stratton, C., Jamila Reid, M., & Stoolmiller, M. (2008). Preventing conduct problems and

improving school readiness: Evaluation of the incredible years teacher and child training programs in high-risk schools.Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(5), 471–488. Wong, M., Bost, K. K., Shin, N., Verissomo, M., Maia, J., Monteiro, L.,…Vaughn, B. E. (2011).

Preschool children’s mental representations of attachment: Antecedents in their secure base behaviors and maternal attachment scripts.Attachment & Human Development, 13(5), 489–502.

D

ow

nl

oa

de

d by [Roya

l H

ol

low

ay, U

ni

ve

rs

it

y of L

ondon] a

t 08:

56 10 J

anua