When crisis arises and the need for change confronts individuals: Trust for Accounting and Accounting for Trust

Cristiano Busco University of Manchester, UK

Manchester School of Accounting and Finance Crawford House, Booth Street East

Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

Angelo Riccaboni University of Siena, Italy

Robert W. Scapens University of Manchester, UK and University of Groningen, Netherlands

1) Introduction

In focusing on individual learning, the objective of this paper is to illustrate a theoretical framework for interpreting the role of management accounting systems within processes of transition and, importantly, their intertwined constitution with the emergence of feelings of trust/distrust for change. The paper starts from a position which conceptualises accounting practices as a set of organisational rules, roles and routines. It is argued that when crisis arises, and the need for change confronts individuals, processes of individual learning encompasses a tension between habitual and intentional patterns of interaction. This requires a multi-levelled conception of human consciousness to interpret the way in which accounting practices interplay with feelings of trust for change in managing such tension. Thus, by exploring the recursive relationship which links cognitive schemes and behavioural practices in the inherent stability and change of organisational and individual life, we make use of insights from sociology of knowledge and cognitive psychology for extending and further refining the institutional framework of accounting change developed by Burns and Scapens (2000).

Although the focus of the analysis is placed at the level of individual, the process of agent construction need to be continuously explored in the light of a wider social context in which agency operates. Humans constitution represents a social enterprise, “homo sapiens is always, and in the same measure, homo socius” (Berger and Luckmann, 1966, p. 69; emphasis in the original). Such consideration seems particularly appropriate in times of global and intense competition, where organisations are constantly required to redefine their identity and adapt their structures to the shifting requirements and features of the market environment. Although continuous in its nature, the need to change is particularly intense in specific critical circumstances, where individuals are increasingly asked for a prompt re-definition of their existing knowledge end expertise. In particular, the need to face the

leaders to rely on accounting and control systems in managing processes of transitions (see Laughlin, 1991).

The role of accounting and control systems within processes of organisational learning and transformation has been widely debated in the literature (Hopwood, 1987; Argyris, 1990; Dent, 1990; Gray, 1990; Cobb et.al., 1995; Otley and Berry, 1994; Coad, 1995; Kloot, 1997). Multiple contributions have illustrated the potential to rely on accounting for visualising, analysing and measuring the current “health” of a business, questioning the operational and managerial strategies implemented and, eventually, justifying new paths of ‘action’

(Hopwood, 1990; Ezzamel et al., 1998). In particular, there is a general agreement on the argument that systems of measurement and accountability display the potential for making the visible reality calculable (or accountable) by translating stock market driven ‘pressures’ into a specific set of quantifiable financial targets that are linked to production processes and business practices (Ezzamel et al., 1999), promoting employee identification with and

commitment to specific values and operative philosophies (Jazayeri and Hopper, 1999), improving intra-organisational communication by infusing managers and ‘non-accountants’ with a common financial vocabulary for ‘reading’ the state of the business (Roberts and Scapens, 1990, Busco et al., 2000).

When crisis arises, and organisations face the need for a rapid transformation, accounting practices, along with other organisational systems, are likely to play an important role in favouring individual’s responses to change, which may be either guided by routinised behaviour and habits of thought or by the intervention of rational deliberation. Management accounting systems act as repositories and carriers of organisational and individual memory (Nelson and Winter, 1982; Busco et al., 2000). Such systems can be proactive towards processes of change by promoting searching and experimentation, as well as they may prevent the questioning of existing knowledge and cultural assumptions (Hopwood, 1987; Dent, 1990; Argyris, 1990). The intertwined relationship which links management control practices and organisational learning has been explored by Kloot (1997, p. 69), who argues that “management control systems affect the understanding of what those changes mean, how and what solutions might be generated, and a perception of whether the time has come to uncouple the organization from old structures and operating paradigms to move to new structures and paradigms”. Even though knowledge is then “transferred” to organisation, learning is a process which originally concerns the individual sphere. However, the way in which individual processes of learning occur between tacit (i.e., unconscious) and purposeful (i.e., conscious) behaviour is still far from being clear and deserves further investigation.

In entering such a debate, the emphasis of this contribution is placed on trust. The intention is to explore whether and, eventually, how the emergence of accounting-driven feelings of trust for change have the potential to challenge those activities which are generally governed by habitual ways of thinking, while opening possibility for conscious or rational deliberation. Being strictly linked with the constitution of agent’s personality, trust as a phenomenon generally refers to the expectations that people have for the others’ behaviour: “to be able to trust another person is to be able to rely upon that person to produce a range of anticipated responses” (Giddens, 1987, p. 136). Although focused on an individual level of analysis, this paper does not lose sight that trust is a socially constructed psychological condition. “People work collectively to form this bond we call trust” argue Weber and Carter, who continue by claiming that “[trust] is not an innate facet of a pre-ordained personality; it is a product of human social relationship … [trust] acknowledges the interactional basis of the emergent relationship, a relationship in which we both act and are acted upon” (1998, p. 21). Thus, far from having sole cognitive or individual grounds, we conceptualise trust as a phenomenon built (or not) in practices, within ongoing processes of learning and interaction.

make sense of the specific ‘reality’ in which they live. Such activities represent a “presentational” ground (base) to create and sustain feelings of trust in the context of interaction (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Seal and Vincent-Jones, 1997). Accordingly, by departing from an interpretation of the possible psychological conditions experienced during processes of individual learning, this paper seeks to develop a framework for interpreting, when crisis arises, the recursive relationship which links the emergence of feelings of trust/distrust for change with the enactment and reproduction of management accounting systems. For this purpose, we begin by recalling some of the contributions that conceptualise accounting practices as constructed and embedded within those “trustworthy” rationales which sustain routinised patterns of behaviour.

2) Coping with learning and change: accounting practices as organisational routines During the 1990s, a growing number of scholars have described accounting systems as organisational routines (see, among others, Roberts and Scapens, 1990; Dent, 1991; Scapens, 1994; Mouritsen, 1994; Burns and Scapens, 2000; Burns, 2000). Either directly or indirectly, such contributions seem to be deeply influenced by the notable work of Nelson and Winter (1982) on evolutionary economics. By portraying the routinization of activity as the most important form of storage of the organizational knowledge, Nelson and Winter describe routines as the means through which ‘organisational memory’ is produced and reproduced in practice; they continuously synthesise action and thought in the enactment of social life. Significantly, according to these authors, “one area of firm behaviour that plainly is governed by a highly structured set of routines is accounting” (1982, p. 410; emphasis added).

Routines represent the behavioural-level manifestation of an institutionalised cultural order. For this reason, they assist individuals to cope with the uncertainties that characterise their social experience1. Habits of thought and routinised patterns of behaviour generally store and carry an innate sense of stability and predictability through time and space. Indeed, they provide individuals with a practical background necessary to assess the complexity of specific situations and, subsequently, make the appropriate decisions. When shared

organisationally, their strength is reinforced by the ability to reduce those conflicts which tend to emerge in social settings. As stressed by Nelson and Winter, “routine operation involves a comprehensive truce in interorganizational conflict … (and) the fear of breaking the truce is, in general, a powerful force tending to hold organizations on the path of relatively inflexible routine” (1982, p. 110-112; emphasis added).

However, although embedded and established in individuals’ memories, routines do change over time. There is always the possibility for a breakdown of behavioural regularities. As suggested by Lawson, “there will be moments of crisis situations or structural breaks when existing conventions or social practices are disrupted” (1985, p. 920). Recently, the

‘cognitive’ extent of such transformations, as addressed in the distinction between

evolutionary/revolutionary change (see Nelson and Winter, 1982), first-order and second-order change (Bartunek and Moch, 1987), reorientation and colonization (Laughlin, 1991), has been widely debated in the accounting literature (see Laughlin, 1991; Burns and Scapens, 2000; Busco et al.,2000).

Aiming to extend this debate, our contribution focuses on the learning conditions involved in agents’ processes of behavioural and cognitive redefinition. In these situations, the

emergence of feelings of ‘trust for change’ seems to play a pivotal role. Per se, the individual-level of analysis implies an accurate interpretation of the psychological conditions needed for

1

breaking thebehavioural and cognitive truce sustained by organisational routines.

Purposively designed by the management and consciously/unconsciously drawn upon by organisational members, accounting systems display the potential to act as devices within the search for stability or change. For these reasons, accounting systems as set of practices and trust/distrust for change as a phenomenon seem to be recursively linked. In particular, whereas the cognitive realm encompasses accounting meanings within mental schemes, the behavioural realm embodies feelings of trust/distrust within organisational practices and activities. As suggested below, when organisations face a crisis and, consequently, members experience the pressure for a prompt “cultural” re-orientation, the outcome of such a process is far from being obvious and needs to be explored, within the specific organisational context, as a result of the tension between individuals’ perception of processes of change and their existing stocks of knowledge.

Accounting ‘routinisation’ and processes of change – When accounting is constructed and embedded within those “trustworthy” rationales which sustain organisational routine, it is likely to be employed to confront environmental disturbances or organisational crises, and to reconstitute the previous conditions of ‘safety’. In such situations, a sort of ‘trust for

accounting’ arises, and accounting/accountants are welcome in the search for a solution. Conversely, when used as ad hoc measures detached from any rationales or deep common understanding, accounting systems can be marginalised and/or perceived as the focus of conflict. A fascinating point of departure for enquiring about the role played by accounting routines within the ongoing process of organisational learning and change is the case of Ferac International, a UK-based multinational, multi-divisional company. The case was first described by Roberts and Scapens (1990) and, then, further expanded by Scapens and Burns (1996). Jointly analysed, the overall picture presents a comparison and interpretation of two contrasting situations within Ferac International, which concern the Plastics and Chemicals divisions.

Within the Plastics division, accounting meanings were deeply involved in the constitution of organisational reality. Thus, although managers did not understand their business exclusively in accounting terms, they manifested a high degree of financial literacy, which revealed management accounting to be one of the major internal sources of information. Although challenged and debated, accounting represented a commonly-accepted way of

understanding organisational activities and making sense of the business conditions and events. Such a ‘position’ had important implications for accounting language. Eventually, accounting terms and concepts were embedded in the deeply-rooted assumptions and knowledge displayed by organisational members, who were then able to routinise their employment to learn about and make sense of their own actions, the actions of others and, importantly, the contingencies of the market. Differently, within Chemicals, the understanding of accounting routines was constrained inside the financial department. This division of Ferac International used different types of routines, which were more production-oriented. Among the other factors, this situation resulted from the Administration Director’s powerful role and strategic policies, which by controlling the production planning process, drove managers’ attention towards the concerns of production.

groups characterised by two different sub-cultures. In practice, while accountants tended to confront managers, rather than supporting their decision making, at the same time,

managers could not find any financial background to understand and co-operate with the accountants. As a consequence, this situation distanced the accountants from managers and their productive concerns.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the conflict emerged in Chemicals, was not experienced in Plastics. In fact, when Ferac International’s crisis put pressure on the cash flow of Plastics, the

managers and accountants worked in concert to find the least painful ways of facing the mutual problems. Indeed, such co-operation was favoured by a shared financial knowledge. In particular, the accounting-driven imprinting of the managers and, crucially, its routinised enactment through time, enabled those terms and practices to be employed within processes of learning and organisational transformation. Thus, whereas in Chemicals, the financial crisis made accounting systems the focus of conflict and the source of the problems, in Plastics, accounting language and key tools represented an important means for dealing with the crisis and for seeking stability, i.e., a common and trust-worthy ground for reaching a possible solution to the problems identified.

A detailed explanation of the contingent reasons which caused such differences in the conceptualisation and use of management accounting systems within Ferac International are beyond the objectives of this contribution. Indeed, they are grounded in the specific contexts, histories and individuals involved in the two divisions (see Roberts and Scapens, 1990 and Scapens and Burns, 1996). However, additional to the emergence of two distinct sub-cultures within the company, in view of the purposes of this paper, the insights of the case are helpful to highlight how accounting routines, as well as other sets of organisational practices, have the potential to play a different role according to the extent to which they are perceived and institutionalised within individuals’ interpretative schemes. This seems particularly relevant when individuals are involved in rapid and uncomfortable changes, which challenge existing convention and behavioural regularities.

By providing a mental framework able to inform routinised patterns of behaviour, taken-for-granted assumptions (i.e., institutions) reduce the complexity which individuals have to cope with on a day-to-day basis. As suggested by studies on cognitive psychology and cultural anthropology, agents rely on concepts and cognitive frames to recall their past experiences and make sense of the stimuli which they face in contexts of social interaction (Douglas, 1987; Lloyd, 1972). Generally, these processes involve an evolutionary or path-dependent route where existing routines and habits of thought are reinforced over time (see Burns and Scapens, 2000). However, when crisis arises, such a “cumulative” process of change may be disrupted by specific environmental disturbances or endogenous shocks, which lead to a breakdown of the former courses of action and cause developments along different paths. In these situations, processes of learning encompasses a tension between the securities and safety of the past, as encoded in organisational routines and behavioural regularities, and the opportunities and threats of the future, as manifested by/through the new “stimuli”

experienced.

refining the institutional framework of accounting change developed by Burns and Scapens (2000).

The structure of the paper follows. Section 3 discusses the psychological strength of

routinised patterns of behaviour within processes of learning. We begin by exploring agents’ biological need for habitualization, and then we stress the tension that may arise between repeated and purposeful behaviour. Next, section 4 outlines the theoretical framework developed for interpreting the linkages between accounting systems and feelings of trust for change. In particular, we illustrate the constitution of accounting between those processes of knowledge recall and anxieties management which characterise phases of individual

learning. Then, section 5 describes how the framework can be employed to interpret the role of management accounting systems within processes of rapid organisational change, which imply a profound cognitive and behavioural redefinition of the individual. For this purpose, we draw on the insights of two case studies for explaining the use of the model. Finally, section 6 ends this work by summarizing the key features of the framework illustrated and the implications for future research.

3) The strength of routines within processes of learning: exploring agency constitution between habitualized and purposeful behaviour

The issue of learning has increasingly gained attention within the organisational context. The uncertainty and turbulence that characterise the current business environment have enhanced the need for flexible organisations, which are required to cope and adapt to a series of

heterogeneous social, cultural and economic factors at an increasingly faster rate. This

ongoing process of adaptation and transformation, in which contemporary organisations must engage, is dependent upon their ability to learn and regenerate themselves. Interpreting such a process, where the values and the assumptions embedded in existing culture play a key role, implies to explore the psychological strength of institutionalised stocks of knowledge over the process of learning. Moreover, since organisations learn through their members, an interdisciplinary perspective is required to explore how individual learning occurs (see Hedberg, 1981; Cohen, 1991; Huber, 1991; Kim, 1993). In particular, we argue that it is crucial to understand where the tension between routinized and purposeful behaviour come from, and why it lie at the very heart of processes of change. Thus, while combining

sociological, psychological and organisation theory insights, we start our discussion by linking processes of “routinization” to the intrinsic characteristics and needs of agency.

Interpreting agents’ biological need for routinization – For the purposes of our paper it is fundamental to interpret the motivational aspects which lie behind the routinisation of social practices. Berger and Luckmann (1966) ground on Gehlen’s philosophical anthropology (1956), Schütz’ phenomenological approach (1972) and Mead’s social psychology contribution (1934) to explore the mechanisms through which a shared cultural order is continually produced and reproduced in light of the “biological” qualities of individuals. Significantly, they portray the formative causes of social experience as anthropological in nature: ‘the human organism lacks the necessary biological means to provide stability for human conduct’ (1966, p. 69). Thus, Berger and Luckmann conceptualise social order as emerging from the need to compensate and support human nature, by providing it with those stabilising cognitive and normative structures which are biologically absent. This is achieved through processes of routinization, through which agents are able to retain the knowledge acquired during their social experiences, and cope with reality of every day life without questioning all the time its traits and characteristics.

According to Berger and Luckmann, the cultural order of any society or organisation can be described as a never-ending “social product” which combines both stability, through the enactment of repeated patterns of behaviour, and potential for change. The latter is guaranteed by the “world-openness” which characterises agents’ relationship to their

environment (Berger and Luckmann, 1966, p. 65). By showing pragmatic formative causes, “routinization” provides individuals with a sense of relief that is needed for coping with the anxieties which characterise the contexts of interaction. As the authors illustrate:

“Habitualization carries with it the important psychological gain that choices are narrowed … This frees the individual from the burden of ‘all those decisions’, providing a psychological relief that has its basis in man’s undirected instinctual structure. Habitualization provides the direction and the specialization of activity that is lacking in man’s biological equipment, thus relieving the accumulation of tensions that result from undirected drives” (Berger and Luckmann, 1966, p. 71, emphasis added).

Following the lines traced by Berger and Luckmann, Giddens (1984) stresses the importance of routinised patterns of behaviour in the continuity and ordering of social life. In particular, he relies on the Freudian perspective of personality and on Erikson’s ego-psychology (1963) to illustrate his “theory of the subject” as grounded on the interplay between the development of personality, processes of routinisation and the reflexive monitoring of action. Giddens’ perspective is strongly focussed on the development of human personality between situations of autonomy and trust, and on their struggle with “anxieties management”. As sustained by the author, “the motivational components of the infantile and adult personality derive from a generalized orientation to the avoidance of anxiety and the preservation of self-esteem against the ‘flooding through’ of shame and guilt” (1984, p. 57). In such a

perspective, humans’ fundamental need for ontological security is portrayed to be at the base of the unconscious or “basic security system”.

Ontological security, which is presented as being found in basic anxiety-controlling

mechanisms, is grounded in the methods developed during the infant’s pre-linguistic stage to cope with anxiety and, later, sustained through the enactment of predictable routines in social interaction. Thus, the deepest layer of ontological security is to be found in trust. As Giddens suggests, “the generation of feelings of trust in others, as the deepest-lying element of the basic security system, depends substantially upon predictable and caring routines” (1984, p. 53). Following the lines proposed by Erikson, Giddens argues how the formation of the subject between conditions of trust and mistrust, autonomy and doubt, initiative and guilt, which individuals experience during processes of growth and personality development, encompasses a management of tensions. Such tensions are experienced to fulfil the organic (i.e., biologically-based) needs of the subject. Ultimately, the search for a sense of trust in continuity and sameness “explains, to a large extent, why agents routinely reproduce social terms, even those which they might readily recognize as excessively coercive” (Macintosh and Scapens, 1990, p. 459).

Human behaviour is not exclusively dependent upon psychological mechanisms embedded within the personality of the individuals. Rather, the existence of agency is “mediated by the social relations which individuals sustain in the routine practices of their daily lives” (Giddens, 1984, p. 50). In particular, as emphasised by Giddens (1984, p.60), “if the subject cannot be grasped save through the reflexive constitution of daily activities in social practices, we cannot understand the mechanics of personality apart from the routines of day-to-day life through which the body passes and which the agent produces and reproduces”. This

illustrates the twofold storage of knowledge which is maintained both as memory traces and within routinised patterns of behaviour. Thus, by performing taken-for-granted

On the other hand, besides their self-reproduction through social interaction, routines as well as their level of certainty and predictability are radically disrupted in ‘critical situations’. When such episodes occur, anxiety swamps the behavioural rituals habitually performed within the organisation. In so doing, by creating “circumstances of radical disjuncture of an

unpredictable kind which affect substantial numbers of individuals”, these events “threaten or destroy the certitudes of institutionalised routines”and unlock possibilities for change

(Giddens, 1984, p. 61, emphasis added). In this sense, change and learning needs to be interpreted as an ongoing re-examination, although at different levels of consciousness, of the stored knowledge which provides ‘position-practice’ incumbents with a sense of ontological security. Indeed, for learning to happen, individuals seem to require a sort of “trust for change” which enable them to question the sense of safety carried by existing routines. Within the next section, the espoused “theory of the subject” and the process of routinization are linked to the issue of individual learning by means of Schein’s anxiety-driven perspective on change.

The processes of learning between routinized and purposeful behaviour: on managing individual anxieties – Considering the objectives of this paper, the question of learning is central. When individuals ‘meet’ a need for change, they face a request for learning which inevitably accompanies such a process. In a different contribution, we define change as “the ongoing process of cognitive and behavioural definition and re-definition which influences agents’ motivation for action” (see Busco et al., 2000). At the same time as linking processes of transformation to the agents’ motivation for action, this definition conveys the two different levels at which learning and change may occur: cognitive and behavioural. This is also consistent with the interpretation of organisational culture, which is conceptualised as a set of common understandings and assumptions, stored both as memory traces and within

routinised pattern of behaviour.

Clearly, it would be difficult to inquire about the way in which accounting practices and

feelings of trust for change are linked within phases of transformation, without interpreting the process of learning itself. In that respect, a description of what has been referred to as

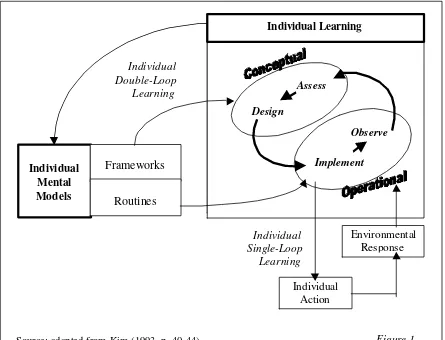

‘Experiential Learning theory’ follows. By distinguishing two levels of learning, Kim (1993, p. 38) shows how learning encompasses “(1) the acquisition of skill or know-how, which implies the physical ability to produce some action, and (2) the acquisition of know-why, which implies the ability to articulate a conceptual understanding of an experience” (see Figure 1). In line with the contribution of Argyris and Schon (1978/1985), Kolb (1984) and Senge

(1990), Kim describes such dimensions as involving both thought and action, the ‘conceptual’ and the ‘operational’ realm. Further, relying on the contribution of Lewin, he suggests how in learning “a person continually cycles through a process of having a concrete experience, making observations and reflections on that experience, forming abstract concepts and generalizations based on those reflections, and testing those ideas in new situations, which leads to another concrete experience” (1993, p.38). Similarly, such a process has been portrayed by Schein (1987) as the observation-emotional reaction-judgement-intervention cycle of learning.

[Insert Figure 1 about here]

through experience, the role of ‘memory’ is fundamental for the retention of whatever has been learnt.

However, memory is not involved exclusively with storing. Thus, in interpreting the process of individual learning, Kim relies on Senge’s contribution to point out the importance of ‘mental models’ as active structures, able to influence what an individual sees and does. Mental models include explicit and implicit understanding which, consciously or unconsciously, provide an ontological construction to interpret new situations in light of the existent stocks of knowledge. Finally, mental models embody two components which refer to the possible different levels of learning. Thus, ‘operational learning’, which concerns the know-how acquired at the procedural level, is captured and stored within mental routines, while

‘conceptual learning’, which involves the deep-rooted assumptions and values characterising the individual knowledge, informs the existing mental frameworks.

Within his description of individual learning, Schein emphasises the key role of “anxieties”. According to Schein (1992/1993), in order to cope with the anxiety which arises in contexts of social interaction, agents are constantly looking for some degree of psychological safety and security. Once such levels are achieved, since unlearning processes are “uncomfortable and anxiety-producing” (1999, p.115), this sense of safety is generally maintained through the enactment of a number of repeated behavioural routines through which people tend to avoid cognitive and behavioural changes. For these reasons, processes of learning and change occur when a series of unfreezing and re-freezing forces perform in an appropriate balance. Such forces are represented by (1) mechanisms of disconfirmation, (2) induction of guilt or survival anxiety, (3) creation of psychological safety and the overcoming of learning anxiety2 and finally, once new solutions have been successfully experienced and validated, by a (4) cognitive redefinition and sedimentation of the key concepts.

The perspective developed by Schein considers “disconfirmation” as a key psychological element in interpreting (and promoting) episodes of change. In particular, mechanisms of disconfirmation lie at the very heart of processes of learning and transformation since they involve a form of frustration and apprehension generated by data or situations that threaten human predictions or expectations. However, disconfirming information are not enough for change to occur. Thus, in order to take such psychological threats seriously and motivate individuals to change, this process must stimulate what Schein calls survival anxiety, i.e. “the fear, shame or guilt associated with not learning anything new” (1993, p. 88). Although survival anxiety or guilt arises when disconfirming data are considered valid and relevant, what typically obstacle agents to develop such a feeling, and causes defensive reaction, is a second kind of anxiety which Schein calls learning anxiety, i.e. “the feeling that is associated with an inhability or unwillingness to learn something new because it appears too difficult or disruptive” (1993, p. 86). The latter type of anxiety is connected to the psychological make-up of individuals as conceptualised by Berger and Luckmann, and Giddens, and refers to the sustainability of a sense of ‘ontological security’ or ‘psychological safety’ which characterise individuals’ biological structure and needs. In fact, according to Schein, “ … human systems seek homeostasis and equilibrium. We prefer a predictable stable world, and we do not let our creative energies out unless our psychological world is reasonably stable” (1993, p. 88).

Learning pathways are closely linked to the “strength” of the existent organisational culture3. “It is the history of past success and our human need to have a stable and predictable

2

In earlier works Schein (1993) calls survival anxiety as “Anxiety 1” and learning anxiety as “Anxiety 2”. 3

environment that gives culture such a force. Culture is the accumulation of past learning and thus reflects past successes, but some cultural assumptions and behavioural rituals can become so stable that they are difficult to unlearn even when they become dysfunctional” (Schein, 1993, p. 87). Thus, processes of unlearning are emotionally difficult because doing things the old and shared way can make life easier. Poor adaptation or insufficiency in fulfilling other expectations often looks less dangerous than risking failure in the learning processes. Schein portrays learning anxiety as the fundamental restraining force which, by arising in direct proportion to the amount of disconfirmation episodes, might enable the maintenance of the equilibrium embedded in defensive routines. Eventually, in interpreting the processes of transformation and change, he proposes the twofold and, to a certain

extent, paradoxical role of anxiety, which although “prevents learning, … is necessary to start learning as well” (Schein, 1993, p. 89, emphasis added).

The enquiry that informs the contents of this paper has purposely been framed within a ‘precise’ time-space context. The objective is to interpret the intertwined constitution of accounting systems and feeling of trust for change, when critical situations arise and

routines-driven individuals face the need for rapid re-orientation. Furthermore, since we build on the literature that conceptualises management accounting systems as a set of

organisational routines, it is argued that an interdisciplinary perspective of study is needed. Thus, by drawing on a series of disciplines, which range from ego-psychology to sociology of knowledge, from organisation theory to cognitive sciences, the argument is developed through an approach which emphasises the strength of habitualized behaviour within the constitution of agency and, consequently, recognises the cognitive tension which the individual has to face during processes of learning. As illustrated in the next section, for interpreting the role of accounting systems in these phases of cognitive and behavioural change, it is necessary to explore their constitution and impact within the process of knowledge recall experienced by the individuals.

4) Accounting systems and feeling of trust for change within processes of learning: towards an interpretative framework

The conceptualisation of “trust for change” – Together with organisational rules and roles, the enactment of routines enables individuals to attain a status of cognitive and behavioural stability which they are biologically missing (see Busco et al.2000). Routines embody an ontological status of security that allows the actors to actively participate in the production and reproduction of their knowledge and of the wider setting wherein they live. Additionally, by providing individuals with a motivation for action, they represent important means for coping with survival anxiety. As suggested by Schein, “behavioural rituals can become so stable that they are difficult to unlearn even when they become dysfunctional” (1993, p. 87). Giddens’ theory of the subject has been criticised by Wilmott (1997), who maintains that anxiety does not accompany individuals’ experience per se but, rather, it emerges when an attachment to routines is severed. “Far from providing any deep sense of ontological security”, argues the author, “seeking to contain anxiety through immersion in routine can offer only a fitful and ultimately illusory resolution of the existential contradiction of human life” (Willmott, 1997, p.177). However, as argued else were (see Busco et al., 2000), by introducing the concurrent presence of two types of anxieties,the perspective portrayed by Schein enables one to cope with Willmott’s criticisms.

of “trust for change” as that particular feeling or psychological condition experienced by individuals, which allows them to classify episodes or data as disconfirming, and to raise enough survival anxiety to stimulate change, without generating learning anxiety in such a measure that it escalates people’s defensive attitudes.

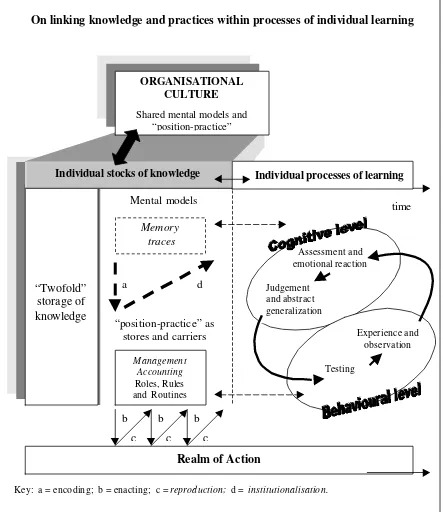

Accounting and Trust for change: exploring their intertwined constitution within processes of learning – By relying on recent contributions on organisational (Laughlin, 1991; Barley and Tolbert, 1997) and management accounting change (Burns and Scapens,2000; Busco et al., 2000), this paper seek to interpret the way in which accounting practices, along with other organisational systems, participate in the process of individual learning and change. In so doing, although the linkages between organisational culture and the individual’s stocks of knowledge are acknowledged, as well as between organisational and individual learning, they are not made explicit in this analysis. Although debated else were (see March and Olsen, 1975; Daft and Weick, 1984; Kim, 1993), the existence of these linkages is taken-for-granted in this paper, were the focus is primarily placed on the realm of the single individual. In particular, a framework is developed for exploring the intertwined constitution of

accounting practices with feelings of trust for change during processes of individual learning and knowledge recalling (see Figure 2)4.

[Insert Figure 2 about here]

The model combines the individual’s twofold storage of knowledge with the corresponding level at which learning occurs. During its ongoing production and reproduction, knowledge is stored and carried both within agents’ mental models, as memory traces, and by means of specific practice’ in which individuals find themselves. Importantly, ‘position-practice’ enables individual’s knowledge to descend the cognitive ladder of abstraction, and to be enacted in specific patterns of behaviour (since memory traces are more abstract than the rules, roles and routines in which they are stored and carried, dotted lines are used for the box and for the arrows a and d). Along with other organisational systems, management accounting roles, rules and routines are likely to play a pivotal role for linking the existing stocks of knowledge within the uninterrupted flow of day-to-day interaction. As stated by Archer (1995), the twofold storage of knowledge proposed by Giddens is rather static, i.e., it does not recognise the different moments in time in which it occurs. Conversely, it needs to be acknowledged that, whereas the cognitive contents which characterise mental models enable and constrain situated interaction synchronically (i.e., at a specific point in time), the ongoing enactment of specific patterns of behaviour allows ‘position-practice’ incumbents to produce and reproduce those stocks of knowledge diachronically (i.e., through their

cumulative influence over time).

The process of individual learning comes alongside the ongoing production and reproduction of knowledge. Although continuous and uninterrupted in its daily development, such a

process can be purposely fragmented for diagnostic purposes. At a specific point in time, any individual is characterised by a particular stock of knowledge which arises from her/his

judgment and abstract generalisation of the social experiences ‘lived’ in the past. In order to balance the biological deficiencies of individuals, the cognitive assumptions which sustain agent’s sense of security/stability are then encoded within specific behavioural stores and carriers, among which are management accounting rules, role and routines (arrow a).

Subsequently, in testing the knowledge gained, the process of learning entails the enactment of those practices in which it has been embedded (arrows b). In this respect, the individual goes through a continuous process of observation and implementation which, being

grounded on the cumulative experience acquired, enables the reproduction of the

4

However, a recognition of the linkages between organisational culture and individual stocks of

practice’ implemented (arrows c). Simultaneously, after having been encoded within the agent’s patterns of behaviour, mental models are potentially open to change or, alternatively, to be confirmed. This happens within a diachronic process of institutionalisation where individuals assess and react to the experience provided by the field (arrow d). Along with the phase of encoding, the validation and institutionalisation of knowledge consist of an ongoing process, rather than single identifiable movements (this explains the broad lines used for arrows a and d).

Once encoded in organisational routines and, then, enacted in situations of co-presence, mental models sustain agents’ social constitutions in practices. Additionally, by enabling and constraining processes of social interactions period by period, they bind time in situated contexts of co-presence. (this justifies the several b and c arrows for each pair of a and d arrows). It is through the production and reproduction of these practices that a certain degree of “order” is achieved, and individuals confirm or revise the stocks of knowledge which drive their behaviour. This process links learning to the existing knowledge and need to be understood, by means of organisational practices, in terms of ‘continuity through

discontinuity’. When the process is limited to the behavioural level, i.e. with the enactment and reproduction of practices and activities, it is there possible to talk about adaptive or single-loop learning. Conversely, when it involves the redefinition of the key cognitive concepts, i.e., it entails the enacting and reproduction of practices and activities, as well as the institutionalisation and re-encoding of new meanings, the occurrence of generative or double-loop learning has to be recognised.

Being rooted at the constitution of individual’s knowledge, organisational practices, among which management accounting systems, have the potential to act as devices for

impeding/promoting situations of learning and transformation. In both cases, they are

implicated in a recursive relationship within the management of trust, where they may act as a ‘positive or ‘negative’ mechanism, as ‘facilitator’ or ‘inhibitor’ of change.Using insights drawn from the work of Veblen (1898/1919), Burns and Scapens introduce the concept of idle curiosity as “the human tendency towards experimentation and innovation which

generates novelty and impetus for change” (2000, p. 18). Burns and Scapens underline how the acknowledgment of agents’ idle curiosity enables Veblen to inject creativity and novelty in his routines-based view of human behaviour. Moreover, this concept allows for the

conceptualisation of stability and change as part of the same, ongoing, evolutionary path. As sustained by Giddens, the inherent indeterminacy of social reproduction makes change intrinsic to every circumstance of social life. He argues that, being based on the repetition of routinised patterns of behaviour, change is “usually incremental”, and that it entails “a slow drift away from a given practice or set of practice at any given location in time space” (1990b, p. 304).

Although one can agree on the continuity of such an action-driven process, it is argued that, far from being a mere intrinsic ‘curiosity’, a deeper investigation of the emergence of feelings of ‘trust for change’ is required. This seems especially true when crisis arises, and

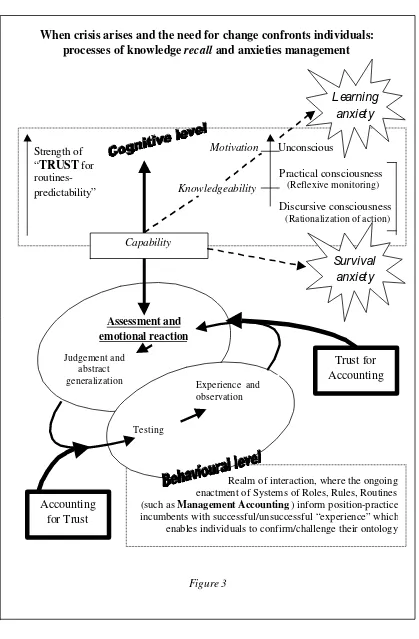

Accounting constitution between processes of knowledge recall and anxieties management – As suggested by Giddens, “routinization is vital to the psychological mechanisms whereby a sense of trust or ontological security is sustained in the daily activities of social life” (1984, p. XXIII; emphasis added). By means of the cognitive contents stored and carried over time and space, routines counterbalance the individual’s biological lacks and drive agency in its

openness to the social experience. Such openness is achieved due to the self-reflective abilities of ‘competent’ individuals, which are knowledgeable. For this reason, they are able to draw from their cognitive stocks to sustain processes of interaction (see Figure 3). These retrieval mechanisms, or processes of recall as Giddens defines them5, are deeply implicated in the constitution actors’ psychological make-up. In particular, the author distinguishes discursive levels of consciousness, that refer to “those forms of recall which the actor is able to express verbally”, from practical consciousness, that “involves recall to which the agent has access in the durée of action without being able to express what he or she thereby ‘knows’”(1984, p. 49). Furthermore, unconscious is portrayed also as a mode of knowledge recall to which “the agent does not have direct access because there is a negative ‘bar’ of some kind inhibiting its unmediated incorporation within the reflexive monitoring of conduct”.

[Insert Figure 3 about here]

Importantly, such a layered view of personality is also reflected within a stratified model of action. Thus, while discursive consciousness parallels the rationalisation of action, practical consciousness entails the reflexive monitoring of conduct, in which individuals tacitly engage their experience and knowledge of the world (Willmott, 1997). Finally, the unconscious embodies the agents’ motivation for action. Repeated patterns of behaviour play a key role in the enactment of individuals’ conduct. “Carried primarily in practical consciousness”, these patterns of behaviour embody the ability to drive “a wedge between the potentially explosive content of the unconscious and the reflexive monitoring of actions which agents display” (Giddens, 1984, p.XXIII). Rooted in organic needs, immersion in routines enables individuals to enhance trust towards the existing social practices, achieve a certain degree of ontological security and cope with possible feelings of survival anxiety.

Nevertheless, when the strength of disconfirming episodes materialise either intentionally or unintentionally within the organisational context, a process of cognitive re-definition is likely to affect individuals’ conduct synchronically. Per se, the cognitive shock does not guarantee the desired change. In fact, the direction of change depends on several contingent factors that characterise the context of interaction. However, by questioning the certainties of the existing knowledge, such episodes force agents to unfreeze their taken-for-granted assumptions, and descend the ladder of abstraction within their mechanisms of recall. Importantly, this opens the possibility for ‘rational’ responses. The assessment of meanings and the subsequent

emotional reaction become grounded at a more ‘conscious’ level. Consequently, the well-foundedness of reality, as expressed in routinised practices, becomes open to be questioned through the transformative capacity of knowledgeable individuals.

Agent’s capability, i.e., the possibility to act otherwise and always make a difference in social interaction, is an intrinsic property of human beings. In view of their knowledgeability,

individuals are always able to rely on their transformative capacity even if they are not fully aware of their potential to intervene in social life. However, when such capability is

consciously drawn upon and then enacted in social settings, the scale of change is more likely to be rapid and intense. Ultimately, the unconscious sense of stability and ontological security provided by past experiences is open to a process of re-definition in light of future possibilities or paradigms. Indeed, it is important here to recognise how ‘trust for change’ is a psychological condition which involves the management of two different types of anxieties,

5

i.e., the enhancement of survival anxiety to unfreeze and, then, to foster the possible

consequences of a conscious use of human capability, as well as the control and limitation of learning anxiety which, on the contrary, tends to sustain people’s defensive attitudes.

At a cognitive level, crises may occur for a variety of endogenous or exogenous reasons which range from specific environmental disturbances arising in the market to ad hoc shocks created by the existing management in order to shake the organisation up (see Argyris, 1977; Laughlin, 1991; Kloot, 1997). Although the individual’s cognitive platform can be challenged by such critical situations, and by those feelings of trust for change which may rationally emerge, this is not enough to give change the desired shape. After having unfrozen the existing knowledge and taken-for-granted assumptions, the possibility for change needs to be continuously maintained in practices, i.e., trust needs to be sustained and driven by specific organisational devices. Thus, when accounting is involved in processes of transformation and used as a catalyst towards change, the achievement of a certain cognitive-based degree of ‘trust for accounting’, is recursively linked to a practice-based degree of ‘accounting for trust’. That is because cognitive and behavioural elements are continuously implicated in the reproduction of social life.

The two realms in which knowledge is stored are linked in a recursive relationship. Thus, whatever the reasons that have questioned the existing situation and opened a possibility for change, the ongoing enactment of behavioural practices will sustain or resist the desired route of cognitive change. Together with other organisational systems, management

accounting practices enable individuals to draw from their stocks of knowledge, make sense of their ongoing processes of interaction and, eventually, enhance the feeling of trust in ‘the new reality’. When this happens, change is generally experienced and, then, consolidated through the enactment and reproduction of organisational activities. As we illustrate in the following section, when organisational leaders build on accounting practices to sustain processes of learning and transformation, the sense of confidence and safety eventually developed through organisation’s successes may favour the constitution and establishment of accounting within the organisational context. On the other hand, when management accounting systems are ‘trapped’ into a general sense of distrust and doubt, they enter a ‘damaging circle’ which contributes to redefine the new reality of everyday life, as well as their roles and functions, in a negative way.

5) Trust for Accounting and Accounting for Trust: discussion and evidence from the field

According to the theoretical framework illustrated in the previous section, for change to happen, participants must take its rationales and, mostly, the connected future opportunities seriously. These conditions are required for overcoming the defensive strength of those psychological forces which biologically tend to prevent processes of individual learning and transformation. Being at the root of the constitution of both the subject (and her/his cognitive and behavioural characteristics) and social object (i.e., contextual institutions),

organisational practices, among which are management accounting systems, have a fundamental part when individuals face a crisis and a consequent need for re-orientation. In particular, portrayed as rules – the formalised statements of procedures, roles – the network of social positions, and routines – the practices habitually in use, they play a pivotal role in supporting the ongoing constitution and redefinition of agency between the existing taken-for-granted assumptions and the new reality of everyday life (see Busco et al., 2000).

thereby permeating the way in which priorities, concerns and worries, and new possibilities for action are expressed” (Hopwood, 1990, p. 9). In addition, particularly during the last decade, several case studies have attempted to investigate the way in which accounting, as well as other organisational systems, participates within the ongoing process of the

production and reproduction of a specific organisational reality (see, among the others, Dent, 1991; Miller and O’Leray, 1994; Scapens and Roberts, 1993; Carmona et al. 1998; Jazayeri and Hopper, 1999). Delivered by Hopwood, the following considerations synthesise such a wide series of contributions, whereas:

“by moulding the patterns of organisational visibility, by extending the range of influence patterns within the organisation, by creating different patterns of interaction and interdependence and by enabling new forms of organisational segmentation to exist, accounting [is] seen as being able to play a positive role in both shifting the pre-conditions for organisational change and in influencing its outcomes, even including the possibilities for its own transformation”(1987, p. 228)

Among the recent contributions which seek to explore the role played by accounting systems within processes of organisational transformation, Ezzamel et al. (1999) provide a useful metaphor for introducing the contents of this section. Thus, synthesising the

philosophy which inspired the process of renovation undertaken by the organisation object of their enquiry, the authors quote a published interview were the ‘burning platform theory of change’ is illustrated by the company CEO. In particular, he argues that:

“ … when the roustabouts are standing on the offshore oil rig and the foreman yells, ‘Jump into the water’, not only won’t they jump but they also won’t feel too kindly towards the foreman. There may be sharks in the water. They’ll jump only when they see themselves the flames shooting up from the platform … The leader’s job is to help everyone see that the platform is burning, whether the flames are apparent or not. The process of change begins when people decide to take the flames seriously and manage by fact, and that means the brutal understanding of reality” (published interview; Ezzamel et al., 1999, p. 39)

The above metaphor opens possibilities for illustrating the role of accounting when

individuals face the need for a prompt change. As suggested by Ezzamel et al., accounting systems have the potential to serve leaders in managing the level of the flames, i.e. to act as disconfirming elements and “construct a powerful discourse that almost literally ‘sets the platform on fire’” (1999, p. 41). For this reason, “‘the burning platform’ metaphor is not simply facilitated by accounting rather, it is an accounting construction” (Ezzamel et al., 1999, p. 42; emphasis in the original). This is certainly a reasonable interpretation which emphasises how accounting and trust for change may act in a recursive mutually-reinforcing way (see section 5.2). Nevertheless, these processes can work in the opposite direction as well, whereas the learning loop takes a mutually-damaging direction (see section 5.1). Thus, management accounting systems are also likely to be swamped in their contents and respectability either when “ad hoc flames” are managed and turned down (i.e., they are met by resistance and distrust) or, in case of “real flames”, when they walk off organisational control (i.e., they threaten the organisation’s survival).

As indicated initially, the aim of this paper is mainly theoretical. We build on earlier studies by Barley and Tolbert (1997) and Burns and Scapens (2000) to develop a framework for

knowledge recall which agents undertake when facing critical situations and pressure for a prompt cognitive and behavioural re-orientation, the framework focuses on management of individual’s anxieties, in which organisational systems, such as accounting, play a key role.

The described theoretical perspective is intended to inform future interpretative field studies. Nevertheless, in the next two sections we discuss the contents from two case studies to illustrate the essential characteristics of the framework. By using insights from the work of Vámosi (2000),

the first case traces the changes which occurred in a Hungarian company (Budapest Chemical Works - BCW) as it was trying to move from government-ownership to a private-control. It describes how the tension between existing “cargoes-of-thoughts” and “the new reality of everyday life” can lead organisational members to develop feelings of trust/distrust for change, the role which accounting is able to play within processes of transition per se, as well as its wider re-constitution within the new organisational reality. The second case, which explores a major post-acquisition cultural change, shows how organisational transformation can be facilitated by the implementation of an organisational-wide system of performance measurement (see Busco et al., 2000). In particular, by emphasising the potential of systems of measurement to act as a language able to crystallise the rationales which underpin

phases of transition and change, the case illustrates the role of management accounting in sustaining and giving direction to processes of learning and individual re-orientation.

5.1 Questioning the existing reality: when distrust turns the flames of change down

In his account on BCW, Vámosi (2000) describes the way in which, together with other contextual factors, participants’ perception of change is likely to affect processes of organisational transformation. After 125-years of history which made BCW the oldest chemical firm in Hungary, the company is presented as facing a phase of autonomous transition, by moving from government to private control. BCW was not taken over by any foreign company or investor, but was privatised and acquired by the existing management. Consequently, the process of transition was characterised by the attempt of BCW’s

management to construct a new ‘organisational identity’ for securing the company survival with the new business environment.

As described by Vámosi, during the process of transition from command to market

economy, BCW’s accounting systems were facing an important challenge. They were asked to refine themselves and re-conceptualise their raison d’être while sustaining the company’s new reality of everyday life. In such a context, the need to adapt to the different business environment, and, eventually, to co-operate with an American consulting firm, was clear to BCW’s top management: “if you are small and slapped in the face, well, then you will start thinking: how can I avoid to get slapped again? Perhaps I should learn to behave

differently”, and again “we know how to deal with the market, but not how to control and manage” (the managing director; Vámosi, 2000, p. 46-47). Despite such degree of

awareness displayed by the management, many employees within BCW were missing what Vámosi calls “seriousness and realism”, which is to be considered an essential element for questioning the existent reality and open possibility for a “real” change.

According to the learning framework portrayed in our paper, when disconfirming information are denied (like ‘Peter and the wolf’) or in other ways defended against, no “survival anxiety” is felt, and, generally, no change will consequently take place. In such situations, as indeed Vámosi recognises, cultural/psychological barriers act as defensive mechanisms which end up preventing learning. The uncertainties and complexities connected to the process of transition enhance actors’ nostalgic feelings for the past. Indeed, as suggested by an employee from the information and personnel department of BCW, “it is hard to say why, [but] you may reach a stage where you just wish that things will remain the same” (Vámosi, 2000, p. 52, emphasis added). The meanings and rationales of the new reality were not fully understood by the BCW employees who, in a certain way, were still constrained from and limited within previous institutions or ‘cargoes-of-thought’.

“Under the old system [command economy] you did not have to think, there was no reason to think, everything was planned and decided by others. It functioned in another way than today, because the relevant ministries interfered. Contrary to today, where nobody comes to tell us that we have to produce 100,000 tons or where we have to sell the goods. And contrary to today, quality was not important then – neither in our products nor in the products from our suppliers. It was definitely easier to be a company then” (employee from the costs and accounts department; Vámosi, 2000, p. 48-49, emphasis added)

Although expressed in a respectful and moderate way, employees’ nostalgia for a stable and predictable working environment is tangible in Vámosi’s report. This was also caused by contingent factors since the transition took place in a period where BCW was facing enormous financial problems caused by a drop in turnover, large debt and unprofitable activities. By employing Schein’s terms, we may argue that the “new” organisational context was not characterised by sufficient psychological safety. Previously, we have discussed the need to balance the amount of threat produced by disconfirming sources to feel survival anxiety, with enough psychological security to overcome learning anxiety and become motivated to change. Due to a variety of contextual (endogenous and exogenous) reasons, such a psychological mechanism has failed to be implemented in BCW where, as a matter of fact, trustfor change has not emerged.

“Liquidity and money problems are visible everywhere. All over the country – no matter where you go… And the consequences are many. They cannot for example invest in capacity, expand the product range or pay good employees well. There is scarcity of money everywhere. And the same situation applies to us” (employee in the export department; Vámosi, 2000, p. 53, emphasis added)

As previously emphasised, being at the root of the constitution of the context of interaction, organisational activities and practices play a key role in shaping the dynamics of change. Thus, along with other organisational systems, management accounting has a constitutive part in defining – through its continuous production and reproduction – the organisation’s identity and culture (see Dent, 1991; Catturi and Riccaboni, 1996; Burns and Scapens, 2000). By storing and carrying the assumptions and the values which characterise the

individual’s stocks of knowledge, such systems of roles, rules and routines lie at the very heart of any process of learning and transformation. Ultimately, they display an innate potential to act as endogenous disconfirming sources, induce survival anxiety, create psychological safety, overcome learning anxiety and, mostly, to actively participate in the cognitive redefinition and sedimentation of the new organisational concepts and rationales.

Nevertheless,, for accounting to enhance trust for change, trust for accounting is needed as well. Such a recursive relationship is not working for the good in BCW. Rather, the

“I have never been in favour of the type of privatization that BCW went through. I would have preferred if we had been able to attract a financially strong company, a company that could afford the necessary investments. Let alone that we cannot afford investments, but we are at a stage where we take one day at a time for cash flow reasons. In order to develop the company it is necessary to invest, but we cannot afford that. I have always had the opinion and dream that one day a large financially strong company would appear …” (production manager)

“In 1996, we have had constant problems with liquidity management… [a] result of our cash flow problems is that we can only afford to examine our present customers’ requirements and wishes – not those of potential, new customers. And I can neither see that we have improved our cash flow management or that our liquidity situation has improved. I hate to be a pessimist, but I would like to see BCW function well. It is an unfortunate situation to like your work and to want BCW to prosper while you are not quite convinced that the others have the ability and will to make BCW into a better and more competitive company. I am not sure that we have the necessary skills and will. I wouldn’t bet on BCW existing in five years” (manager; Vámosi, 2000, p. 55, emphasis added).

Perhaps not surprisingly, within a context where mistrust seems to be prevailing over trust, doubt over autonomy, guilt over initiative, management accounting systems have been trapped in such a ‘contradictory’ loop. Consequently, instead of reinforcing the need for a change, BCW’s accounting practices and, in particular, cash flow management, became an ‘emblem’ of failure to change. As suggested by Mendoza , “due to the fundamental, i.e., deeply ingrained and widespread character of habitual, routinized activities, and the intensive rules implicated in them”, organisational practices represent “the bases for the continuity of social reproduction across time-space” (1997, p. 272, emphasis in the original). Accordingly, within BCW’s evolutionary path, cash flow management has contributed to define and re-construct the new business environment although, unfortunately, in a “roundabout negative way” (Vámosi, 2000, p. 55). Indeed, in line with the ‘burning platform’ metaphor illustrated above, it is possible to affirm how, by turning the flames of change down,distrust has paradoxically burnt accounting potential for supporting the process of transition.

Following the insights of the story reported by Vámosi is reasonable to assert how management accounting practices have been (although deficiently) constituted between “cargoes-of-thoughts” and “the new reality of everyday life”. The transition from command to market economy, from production-oriented rationales to a customer-oriented frame of reference has increased the number of aspects to co-ordinate. Ranging from marketing to costing, from quality assurance to cash management, the management tasks have become much more demanding. Thus, in spite of efficient ‘cargoes’ of technical and administrative capacity inherited from the previous situation, BCW was missing those management skills that were required to successfully face the new business reality.

The “psychological strength” of deeply-rooted mental models is evident in the case illustrated. The habits, perceptions, and rationales historically sedimented within BCW’s existent routines enables ‘position-practice’ incumbents to meet change by resistance. Being constantly ‘recalled’ within daily processes of interaction, those values, assumptions and habits which inform BCW’s organisational culture act as cognitive and behavioural obstacles towards the emergence of possible feeling of trust for change. They resist individual’s processes of learning at all levels. Thus, the difficulties experienced by top-management in abandoning existing “cargoes-of-thought” while coping with the new business environment are illustrated by Vámosi through the words of a

something we have to learn, and many of the old ways of thinking still prevail” (2000, p. 57-58, emphasis added).

The constitution of organisational order between routinised and purposeful behaviours, ‘past’ and ‘present’ raisons d'être, pressures for stability and change, is daily accomplished by each individual while drawing on existing practices and activities. This process of

knowledge recall involves management accounting systems as well. As suggested by Vámosi, “accounting practice is a target for change and an instrument (catalyst) in the process towards a new constitution and institutionalisation” (2000, p. 56, emphasis in the original). This process did not work properly in BCW were a diffuse sense of distrust for change has recursively influenced the social construction of accounting systems in “negative terms”. BCW’s employees failed to perceive accounting as a key instrument to face the anxieties of change. Rather, they identified those systems as part of the problem. This is not always the case. Thus, the potential of management accounting practices to act as an endogenous catalyst factor for enhancing feelings of ‘trust for change’, and actively shape processes of individual learning and organisational transformation, are extensively

discussed in the following section, where the process of privatisation of an Italian mechanical company is explored.

5.2 Breaking and re-establishing the individual’s mental “truce”: the intertwined constitution of accounting and trust

Relying on the insights of an extensive longitudinal study, the case of Nuovo Pignone (NP) provides a useful description of the abilities of accounting systems to ‘unfreeze’, ‘change’ and ‘refreeze’ the individual’s stocks of knowledge, as embedded within mental models and organisational position-practice (see Busco et al., 2000). Established originally in 1842 as Pignone, the name-shift to Nuovo Pignone came into being in 1954 following acquisition by a state-owned holding company. Later, in 1994 NP was acquired by the US multinational, General Electric (GE). Kicked off in 1995, the case focuses on the integration of NP into the GE global organisation. Thus, although various programmes of organisational restructuring were implemented within the company, ranging from downsizing and delayering to

boundaryless working and outsourcing, the process of integration grounded on a major change of NP’s understanding of measurement.

As for systems of measurement, the cultural background of NP was so totally different to GE that a massive process of cognitive and practical redefinition was required. Whereas NP had no widespread tradition of performance measurement, GE’s management and organisational style relied extensively on such systems of control and communication. Before the

acquisition, NP was a stated-owned and largely bureaucratic company that had to produce budgets and various reports for both head office and the state bureaucracy. Used mainly for ceremonial purposes these systems were not integrated into the management processes of NP. Although, such situation did not impede NP in being reasonably profitable, due largely to excellent products and production systems, following the acquisition by GE, significant changes took place. There were two major components of organisational change within NP: the first was the re-design of the company’s systems of accountability, and the second was the subsequent implementation of the Six Sigma Initiative, a new measurement-based quality programme. Importantly, intensive and extensive training programmes supplemented them both.