sPAnish: Accounting For contAct-induced chAnge

MAríAdel Puy cirizA MArco shAPPeck

University of North Texas at Dallas University of North Texas at Dallas

rey roMero

University of Houston-Downtown

This study analyzes the modal functions of the adverb ya in three contact varieties of Spanish: Basque Spanish in the Basque Autono-mous Community, Andean Spanish in contact with Quechua in Ecua-dor, and Judeo-Spanish in Turkey and the Balkans. In comparing the uses of ya among the three Spanish varieties, we apply an approach developed by Mougeon et al. (2005) consisting of the following steps: (1) determine that the feature in the contact variety has the same or similar function in the source language; (2) examine whether the in-novation is the result of an internal process such as overgeneralization or regularization; (3) provide evidence of data militating against, or bolstering, the contact induced hypothesis; and (4) identify a correla-tion between the level of bilingualism in the community and the fre-quency of its innovative use. This four-step methodology is applied in the Basque-, Quechua-, and Turkish-Spanish contact situations in order to establish whether its innovative use of modal ya is empirically shown to be contact-induced.

Keywords: language contact, discourse markers, Andean Spanish, Basque Spanish, Judeo-Spanish

of change through contact, the following four lines of inquiry have been recom-mended: (a) deeper analyses of donor and recipient languages; (b) enrichment through comparisons of corpora from different contact situations and socio-his-torical data; (c) higher quality in descriptions of the speakers who produce the innovation; and (d) increased quantitative analysis of data sets (Silva-Corvalán 1994, Escobar 2000, Van Coetsem 1988, Winford 2003, Mougeon et al. 2005, Poplack & Levey 2010). This trend has led to proposed methodologies to better determine the likelihood that an innovation is related to contact by considering both social and linguistic factors as well as synchronic and diachronic corpora. Studies have shown how corpora-based research can shed light on the differences in which innovations are observed across speakers and communities (Mougeon et al. 2005). Likewise, sociohistorical readings have the potential to explicate the life of a so-called ‘innovative feature’ by clarifying how contact with the recipi -ent language has merely caused a restructuring or overextension of the pragmatic domains in which an existing feature can be used (Silva-Corvalán 1994). All these points of consideration relect the fact that the appearance of innovations is con -ditioned by multiple aspects that act as a threshold for innovative functions of language use (Mougeon et al. 2005).

In this study we focus on the innovative uses of ya in three varieties of Span-ish: Basque Spanish in Bilbao and Bermeo (The Basque Country, Spain); Andean Spanish in Quito and Cotopaxi (Ecuador); and the Judeo-Spanish varieties from Monastir (Macedonia) and Istanbul (Turkey). We have selected these geographi-cally distant varieties in order to better assess whether innovations of ya are actu-ally intrinsic to the linguistic system of Spanish or a result of language contact. We review variants of ya from a methodological perspective by using the frame-work of Mougeon et al. (2005). These authors propose a step-by-step analysis in which both external and internal linguistic phenomena are taken into account for the different Spanish varieties, which will be outlined in section 2.

Although the use of ya can present a wide range of semantic values (e.g. adverbial, discursive, or modal), we analyze solely those innovations found in ya as a modal marker (Urdiales 1973, Girón Alconchel 1991, Garrido 1992, 1993, González 1999). different from the adverbial temporal readings, modal ya bears an emphatic value to express the belief that an event will occur.1

(1) Ya verás cómo todavía viene.

‘Ya you’ll see how he’ll still come.’ (Garrido 1993:224)

In (1), ya does not convey a temporal value, that is, the speaker is not indicat-ing that the interlocutor ‘will already see’. In this case, ya can be substituted by

the afirmation sí que or sí (sí verás como todavía viene) (González 1999). Ac-cording to Garrido, ya carries an epistemic function as a modalized assertion to contradict the interlocutor’s idea that the event will not take place.

1.1.

bAsQue sPAnish ya

.

Several researchers have observed the frequent use of ya in Basque Spanish (González 1999, Oñederra 2001, 2004, Camus-Ber-gareche 2013). González (1999) argues that, different from standard Spanish, ya in Basque Spanish occurs with a modal function emphasizing ‘new information’ (i.e. information not previously mentioned in the discourse).(2) A: ahora han puesto pues un video // pues // allí sale // pues lo que es Lekeitio / y/ y / las costumbres / después las casas que tienen escudo …

B: ya

A: ya (lo) he traído // por- porque no tengo video // he- he

com-prao video pero No tengo video …

A: ‘Now they have prepared a video cassette. There you ind … what is Lekeitio,

And the traditions, then the houses that have a coat of arms … ’ B: ‘I see’

A: ‘I have brought (it). I don’t have a VCR. I have bought a cas

-sette, but I don’t have a VCR … ’ (González 1999:164)

Speaker A starts the conversation by explaining the content of the video and how she brought it along, ya (lo) he traído (‘Ya I have brought (it)’). González argues that ya does not indicate that the speaker ‘has already brought the video’, but rather serves to focus attention on the afirmation that the speaker ‘has actu-ally brought the video’. Thus, ya constitutes new information in the discourse. This usage implies an innovation from modal ya in monolingual varieties where it is employed to compare or contrast ‘old information’ previously mentioned in the discourse (González 1999). The author attributes the ‘new information’ ya in Basque Spanish to the inluence of the Basque particle ba-.

(3) Jonek badakar hori

Jon-ErG ba.brings that

‘Jon is bringing that’ (Hualde & Ortiz de Urbina 2003:498)

(4) Ba-daukat kexarik egiterik?

‘Can I ile any complaint?’ (Hualde & Ortiz de Urbina 2003:297)

(5) Ba-dira sagu-ak etxe honetan

yes-are mouse-dET.PL house this ‘Yes there’s a mouse in this house’ (Laka 1996:58)

In Basque, the preix ba- is employed: when the verb is the most important piece of information of the sentence (3); in yes/no questions that begin with a synthetic verb (4); and to contradict a negative assertion previously stated (5). Therefore, Basque Spanish ya is similar to Basque ba- as it serves to focalize the afirmative value of the verb. Camus-Bergareche (2013) also observes that similar to Basque ba-, afirmative ya in Basque Spanish cannot be employed postverbally.

(6) —¿Qué tal el plato?

—Oye, muy bien, ya me gustan los espaguetis con esta salsa. *—Muy bien, los espaguetis con esta salsa me gustan ya.

—¿How is the dish?

—Hey, really good, ya I like the spaghetti with this sauce. *—Very good, the spaghetti with this sauce I like ya. (Camus-Bergareche 2013:2)

In (6) a temporal reading of ya does not apply; conversely, ya serves to em-phasize the fact that the speaker ‘does like spaghetti’ intensifying the reading of the verb gustar (‘to like’). As Camus-Bergareche shows, the same reading does not apply post-verbally.

González analyzes the uses of temporal, discursive, and modal ya in Basque Spanish among 41 informants, each with different linguistic backgrounds (Span-ish monolinguals and Basque bilinguals) and in contact areas (the high contact coastal and inland areas in Bizkaia, and the low contact area of Bilbao). She inds that the higher frequency of modal ya coincides with Basque-speaking commu-nities whereas lower contact regions (i.e. Bilbao) show fewer cases. Similarly, modal ya is more frequent among Basque dominant speakers than among Spanish monolinguals. González concludes that the appearance of ‘new information’ ya in Basque Spanish is mediated by both internal and external causes. Externally, contact with Basque has provoked an extension in the domains in which modal ya can be employed, concretely with new information. Internally, grammaticaliza-tion tendencies show how adverbs are becoming increasingly intersubjective and oriented to index subtle pragmatic nuances about the point of view of the speaker in the discursive context (González 1999, cf. Traugott and könig 1991).

varieties will serve as a baseline for the study of ya in Andean Spanish and Ju-deo-Spanish. Our contribution to the discussion of the Basque Spanish variety will focus on an analysis of the davies corpus to attest whether a ya with new information is employed in other varieties of Spanish. Moreover, different from González’s study in which both modal afirmative ya with old information (also found in monolingual Spanish varieties), and the modal ya with new information (the Basque Spanish innovation) are counted together in the quantitative analysis, in our data we will only analyze the ya with new information in our data set in order to attest the consistency of the innovation.

1.2.

AndeAn sPAnish ya

. In Andean Spanish, an increased use of double

ya constructions has been observed: ya+[constituents/clauses]+ya (Lee 1997, Feke 2004, Shappeck 2013):(7) Ya me cambió nombre ya

‘Ya s/he changed my name for me ya.’ (Lee 1997:160)

Lee (1997) and Feke (2004) consider the use of this double construction a calque from Quichua -ña which can also be duplicated.

(8) a. Ña huambra-ña ca-shpa

‘He’s becoming ña a young man ña.’ (Catta 1994:187)

b. Michi huañu-jun, ña ñuca-ca alli-mi cani-ña

‘Mercedes is sick (dying), ña I (on the other hand) am ine ña.’

(Catta 1994:187)

(9) Sí, comunicaron pero ya había sido después ya, entonces ya había sido desperdiciado.

‘yes, they communicated (with us), but ya it had been afterwards

ya, so ya it had been wasted.’ (Shappeck 2010)

In (9), the irst ya provides an aspectual value (the fact that the communica-tion has ‘already’ occurred), whereas the second ya acquires a new modalizing value, emphasizing the fact that the event has already taken place. Similar to the preverbal use of ya as a modal marker in monolingual non-contact varieties of Spanish, the use of postverbal ya in Andean Spanish seems to be triggered by the fact that Quechua -ña can also occur postverbally (Shappeck 2013). Another interesting aspect of the behavior of Andean Spanish duplicated ya is the fact that it can serve to focalize different constituents in the sentence.

(10) después, ya mi hija ya tuvo unos diez años ahí vuelta enfermé yo, ahí estuve yo en Quito

‘Afterwards, ya my daughter ya was around 10 years old, and then I got sick, and I was in Quito’. (Shappeck 2010)

The informant in (10) narrates a sequence of events that occurred before her sickness which kept her in bed. In this case, the double construction emphasizes the fact that she got sick when her child was ten years old, focalizing the subject, ‘my daughter’, instead of the verb. The appearance of ya with other constituents that are not verbs seems to parallel the fact that in Quechua –ña can also appear with other constituents (Cerrón-Palomino 1996).

Some questions remain unanswered in the duplicated construction of An-dean Spanish ya. For example, does this double construction occur in non-contact Spanish varieties? And if so, can it happen with other non-verbal constituents? An analysis of the double construction in the davies corpus will shed light on these questions and clarify the extent to which we can consider this feature a contact-induced innovation. We will also provide data from two varieties: low contact va-rieties (from Quito and Lima) and a high contact variety (from Cotopaxi in the Ec-uadorean highlands) to examine the distribution of this feature in the community.

ya. Varol Bornes (1996:223) identiies a Turkish syllabic process with pragmatic implications transposed into Judeo-Spanish. This mechanism known as MühMele repeats the lexical item, but in the second iteration, replaces the irst onset of the lexical item with /m/, as in Judeo-Spanish: livro mivro or ijo mijo. The mühmele implies that the speaker thinks less of the object in question, or that its importance is minimized, and it may even question the deining qualities of such an object: ‘you call that a book?’ ‘What kind of son is that?’ Although no previous study on Judeo-Spanish ya exists, we can conclude that Turkish bilingualism has affected every linguistic component of the language, including its pragmatics.

In both sets of Judeo-Spanish corpora used in this study, we observe a per-vasive use of ya in combination with two predicates: ya ay and ya ez verdad, as illustrated below in examples (11) from Istanbul and (12) from Monastir. Please note that all Judeo-Spanish examples in this paper have been transcribed using the Aki yerushalayim orthography, a highly phonetic version of the Latin alphabet adopted almost universally by modern publications.

(11) En la sivdad ya ay munchos árvoles.

‘In the city ya there are many trees.’ (Romero 2009)

(12) Ya ez vardad lo kwe dizis.

‘Ya it’s true what you are saying.’ (Luria 1930:76)

These combinations with ya are present in the utterance as a grammatical-ized unit, that is, they always appear together with the verb (ez verdad) and with factual predicates. Additionally, these combinations seem to have the pragmatic function of asserting or afirming the truth of those predicates. The speaker uses ya ay and ya ez vardad to commit to the truth of the proposition, as if to emphasize its factuality. In (11), the speaker is emphasizing that ‘there certainly are many trees in the city!’ as if s/he had a direct experience with the knowledge source. Similarly, in (12), the speaker knows for a fact that the listener’s comment is true: ‘I am aware that you are speaking truthfully.’

The higher use of ya ay and ya ez verdad in both varieties of Judeo-Spanish may be the result of language contact with Turkish, which has the evidential sufix

-(I)mIş (the capital “I” indicates vocalic alternations according to a four-vowel harmony; the parenthetical vowel indicates it is added when a verbal stem ends in a vowel). According to Gül (2009:4-5), this verbal sufix indicates several types of evidence as related to its predicate; among them is a synchronic evidential function, through which the speaker asserts the truth of the predicate by empha-sizing it at the time of speech:

‘Behold! So many dresses I have.’ (Gül 2009:4)

Another is a retrospective evidential where the speaker attests to the truth of the predicate by observing traces or evidence of the action.

(14) Yerler ıslak. Yağmur yağ-mış.

‘It’s wet everywhere. It must have rained.’ (Gül 2009:4)

The combinations ya ay and ya ez verdad therefore parallel the synchronic and retrospective evidential functions of the sufix –(I)mIş, as the speaker evalu-ates and emphasizes the truth of predicevalu-ates. Because of their similar functions, as well as the grammaticalization of ya ay and ya ez verdad as units, the evidential sufix –(I)mIş appears as a possible trigger for this innovative usage, if indeed it is due to Turkish contact.

1.4.

outline oF PAPer

.

Initially, contact appears to be the motivating fac-tor since all three above-mentioned varieties have discourse markers (including ya) that seem to mimic the functions of afixes in the source language (Urrutia 1995, Oñaederra 2001 for Basque Spanish; Cerrón-Palomino 1996, Escobar 2000 for Andean Spanish). However, a deeper analysis based on strong empirical data is required to substantiate assertions related to linguistic change through language contact. The ways in which ya functions in monolingual varieties of Spanish would be an example of the type of empirical evidence that is needed (Silva-Corvalán 1994, Hock & Joseph 1996, Mougeon et al. 2005, Poplack & Levey 2010). The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 presents Mougeon et al.’s (2005) methodology. Section 3 accounts for studies that have analyzed the different pragmatic contexts in which modal ya occurs in monolingual varieties and presents a corpus analysis of modal ya using the davies corpus (2002-) to ascertain whether these innovations exist in the donor language. In section 4 we provide a general account of the three linguistic communities and the history of the contact with these three agglutinating, though unrelated, languages (Basque, Quechua, and Turkish).In section 5 we present the data that we have collected applying Mougeon et al.’s (2005) four-step approach. Finally, in section 6 we summarize the evidence that clearly accounts for language-contact changes and examine the areas where empirical results are lacking in light of the new functions of modal ya in Basque Spanish, Andean Spanish, and Judeo-Spanish.frame-work proposed by Mougeon et al. (2005) in their analysis of eight innovations in Ontario French. Concerned by how the notion of language contact has been either ‘overused’ or ‘attacked’ in linguistics, these authors propose a methodological approach with the objective of ‘providing with reasonable conidence that certain innovations attested in the minority language are rooted in contact with the ma-jority one’ (2005:114). This approach has at its core the use of different corpora (including the interlanguage of second language learners of French and informa-tion from genetically related varieties) and a step-by-step approach that analyzes the innovations from the perspective of internal and external factors.

The authors start by distinguishing between overt and covert systemic trans-fers. Overt systemic transfer is deined as a ‘qualitative change in the use of a feature’ (2005:102). For instance, the case of the adverb just in Ontario French which, different from Standard French, can be used after a subject and a clitic pro-noun (e.g. tu juste mets du sel dedans). According to the authors, this innovation implies a qualitative change from the syntax of French since in English just occurs in that syntactic position. Conversely, a covert transfer is not a qualitative innova-tion, but rather ‘a marked increase in the frequency of a feature at the expense of an alternative feature’ (2005:102). This is a relevant distinction as it helps us clas -sify particular cases of language change (e.g. qualitative or quantitative). What follows is a detail summary of the four steps.

2.1.

s

uMMAry oF Four-

steP MethodologicAl Procedure. In Step

1, the researcher must attest whether the observed phenomenon in the recipient language has an equivalent feature in the source language. For example, Ontario French speakers employ the preposition sur (in sur la television or sur la radio) instead of the standard preposition à. The authors trace the semantics of the use of sur to the English use of preposition on. Step 2 focuses on whether the feature in question can actually be attributed to internally-motivated processes such as regularization or analogy. Mougeon et al. (2005) illustrate internally-motivated change in the use of postverbal object pronouns in declarative sentences (15) in-stead of typical preverbal ones in standard French (16). This innovation parallels the English use of postverbal object pronouns, an aspect that raises the possibility that the change has been triggered by contact.(15) Ontario French

On rentre dans la maison pis elle dit à nous autres <Parler en français>

‘We go into the house and she says to us <Speak in French>’

(16) Standard French

Elle nous pogne pis elle nous dit de parler français

‘She catches us and she tells us to speak French’ (Mougeon et al.

2005:105)

The authors debunk the contact hypothesis by observing that a similar ten-dency is also present in the case of other pronominal objects of other non-contact varieties of French e.g., celui/-là, tous, certains, aucuns, etc. Therefore, step 2 proves that this feature is the product of an internal reconiguration in the form of syntactic regularization. Conversely, in the case of the preposition sur, the authors argue that it cannot be considered a case of regularization or other internal pro-cesses, but rather complexiication caused by contact.

Step 3 searches for the particular feature in other varieties of the target lan-guage. Mougeon et al. (2005) consider two categories of varieties: (a) those that could provide evidence militating against contact-based explanations of the inno-vation, and (b) those that could include evidence bolstering the case for contact-induced change. For category (a), the authors include varieties of the target lan-guage spoken in settings where there is little or no lanlan-guage contact (or what they call ‘monolingual’ speech communities); in category (b), they examine varieties of the target language that are in contact with the same source language, but in distinct geographic locations. Their indings show that with the exception of clitic pronouns, the rest of the innovations are not attested in the Quebec City variety where there is little or no contact with English, therefore indicating that the in-novations are contact induced changes. In the case of clitic pronouns, the corpus of Montreal French shows how at least two of the preverbal object pronouns of French le/la (him/her/it) have a tendency to appear postverbally, a inding that shows how change may be related to internally motivated processes.

Finally, in Step 4 the appearance of the feature in the data set is corroborated with the intensity of contact and level of speaker’s bilingualism. In their study, the majority of the innovations are considerably more frequent among Francophones who speak English frequently in high contact areas, even though in some cases, especially when the innovation is not radically different from the traditional form, it can also be found in lower contact areas. After applying the four steps to the eight observable variations in Canadian French, the authors conclude that two factors worked against the adoption of these innovations in the community: (1) when the innovation involves a radical departure from the rules of the monolin-gual norm, and (2) low intensity contact with the source language produces fewer instances of the innovative feature.

the distribution of the feature in the community, but it will also show different inluences that are acting against, or reinforcing, the use of the variant.

3.

ModAl ya in non-contAct vArieties oF sPAnish: stePs 1-3

.

Ap-plying step 1 to the three varieties of Spanish in section 3, we ind that the source languages—Basque, Quechua, and Turkish—bear equivalent features. In Basque Spanish, the modal afirmative ya (‘new information’) serves a similar function as the Basque –ba. In Andean Spanish, the duplication of ya appears to be triggered by the Quechua afix –ña which is also commonly duplicated. Structures such as ya ay and ya ez verdad in Judeo-Spanish may follow the evidential system of Turkish. Our application of Steps 2 and 3 center on addressing internally motivat-ed processes and examining the patterns in other target language varieties, in our case, other varieties of Spanish. For Step 2, we summarize studies that have ana-lyzed the pragmatic scope of ya in other vernacular varieties of Spanish, including Castilian Spanish (Urdiales 1973, Bosque 1980, 1990, Girón-Alconchel 1991, Garrido 1992, 1993) and Mexican Spanish (Lope Blanch 1991, koike 1996). We follow the baseline of pragmatic and semantic uses of ya employed by González (1999) in order to better assess whether the innovations already belong to a larger trend of internal change. For Step 3, we consult the davies corpus to determine whether the innovations existed in particular varieties in the past (e.g., Colonial Spanish) and/or emerge in contemporary monolingual varieties—a method ap-plied to the study in order to conirm the indings in step two.values that express the speaker’s attitude and beliefs towards the proposition. This internal, diachronic development of ya must be taken into consideration when examining contemporary innovations of modal ya in Spanish contact varieties in the current study.

Studies that have focused on synchronic uses of ya have found that the par-ticle can be employed with a range of pragmatic and semantic environments (Bosque 1980, 1990, Urdiales 1973, Lope Blanch 1991, koike 1996, Garrido 1993, González 1999, delbecque & Maldonado 2011, Wilk-racieska 2012). In terms of where ya can occur, Garrido (1993) highlights its itinerant placement in an utterance.

(17) (a) María ya vive aquí. (b) María vive ya aquí. (c) María vive aquí ya. (d) ya vive aquí María. ‘Mary already lives here.’ (Garrido 1993:358)

We can observe how ya can occur preverbally (17a), postverbally (17b), utterance-inally (17c), and utterance-initially (17d). However, there is no study that has analyzed the frequency of ya in each position, or whether ya can appear duplicated as it does in Andean Spanish. despite the fact that ya is mostly known as a temporal/aspectual marker, studies that have analyzed the modal uses of ya have observed how the particle can be used with an emphatic and afirmative value (Pérez-rioja 1987, Garrido 1993, González 1999, Wilk-racieska 2012). Observe the example below:

(18) Ya se sabe que Muti está acostumbrado a las viejas producciones de la Escala, pero su actitud me sigue pareciendo poco profesional.

‘Ya everybody knows that Muti is used to the old productions from Escala but his attitude still seems unprofessional to me.’ (Wilk-racieska 2012:298)

Following earlier research (Pérez-rioja 1987, Garrido 1993, González 1999), Wilk-racieska (2012) describes the use of ya in (18) as an epistemic conversa-tional marker which could be replaced by utterances such as claro or por supues-to. The adverb does not contain a temporal, aspectual value, nor can it be analyzed in presuppositional terms. Its nature is afirmative and emphatic. González (1999) observes how modal ya can be used with factual and nonfactual predicates, but its semantic value changes when employed to describe non-factual events. Compare (19) with (20) below:

‘I know.’ (González 1999:205)

(20) Ya iríamos a América.

‘We would also like to go America.’ (González 1999:205)

With factual predicates (19), ya conveys the semantic value [+emphasis] [+afirmation] because the speaker is sure of the information s/he is providing and therefore emphasizes it. With non-factual predicates (20)—such as descriptions of future events, past inferences, and with hypothetical situations—modal ya car-ries only the semantic value of emphasis, but not afirmation ([+emphasis] [-af -irm]) since the speaker cannot conirm that the event actually occurred (González 1999).

González (1999) also analyzes the pragmatic contexts in which modal ya occurs in monolingual varieties, inding that it is used primarily to emphasize old information that has already been activated or evoked in the discourse by either interlocutor in the conversation (see Prince 1981, Silva-Corvalán 1986). Two dif-ferent contextual distributions are distinguished:

-Ya employed with propositions that compare or contrast information previ-ously mentioned in the discourse (cf. Bosque 1980).

-Ya in non-comparative contexts to emphasize information previously stated in the discourse without contrasting or comparing it.

In (21), the author presents modal afirmative ya with comparative predicates in which the speaker identiies himself as an example of the information already presented in the discourse.

(21) A: Claro antes igual era más peligroso ¿no?

B: sí, sí, sí, según, a, a lo mejor te me-, te meten un golpe, un barco, a nosotros ya nos pegó, andando aquí a unas treinta millas de … San Sebastián, nos vino un barco, nosotros trabajábamos- colocando las cajas se llaman cajas, colocando anchoas, nos pegó

uno de Bermeo.

A: ‘I see. Before it was probably more dangerous, right?’ B: ‘yes. yes, yes. It depends. A boat could hit you. We were hit once when we were about thirty miles from … San Sebastian. A boat came towards us, we were working placing boxes, they are called boxes, placing boxes with anchovies. A boat from Bermeo

In (21), the speaker explains that one of the problems with ishing during bad weather is that you could get hit by a larger boat. The bolded sentence ya nos pegó (‘ya it hit us’) identiies the speaker and his crew as having experienced a collision. For González, ya highlights the fact that the speaker and his crew ex-perienced the danger once, which illustrates the discourse topic. Furthermore, the author argues that these contexts allow for the use of an afirmative sí que (sí a nosotros sí que nos pasó) with the same meaning.

Modal afirmative ya can also occur in non-comparative contexts where the speaker emphasizes information without comparing or contrasting it. See the ex-amples below:

(22) A: … yo estoy aquí, veo el sol, y ahí estoy en la playa, o a … no sé caminar por aquí

B: ya hay paseos aquí bonitos, por ejemplo tienes cerquita, son

paseos peatonales, por ejemplo …

A: … ‘I am here, see the sun and there I go to the beach. Or to walk around.’

B: ‘There are nice paths here. For instance you have very close

… these are walking paths. For instance … ’ (González 1999:169)

In (22), speaker A makes the irst explicit reference to the existence of side -walks along the coast. Speaker B restates the information by conirming the ex -istence of these paths in the town. González argues that in this case, modal ya emphasizes and asserts information already activated in the discourse without comparing or contrasting it with information previously mentioned. Graph 1 has been adapted from González’s (1999) research where the semantic and pragmatic uses of ya in monolingual Spanish varieties are diagrammed.

Temporal Discursive Modal

Factual Non-Factual ya

Non-Comparative Comparative/contrastive

We have chosen the functionalist deinition of modal ya expounded in González (1999) which is based on the semantic features of emphasis [+/- empha-sis] and afirmation [+/-afirm]. With factual predicates, the modal function of ya emphasizes [+emphasis] the belief of the speaker that the event has taken place or will take place, adding a [+ afirm] value to factual predicates. Conversely, with non-factual information, modal ya is used to emphasize [+emphasis] but not af-irm [-afaf-irm], since it is used with past, hypothetical predicates.

3.2.

AnAlysis

oF the dAvies corPus. Our analysis of the davies (2002-)

corpus will help answer the following questions about the innovative uses of mod-al ya:1. Can we ind evidence that the Basque Spanish innovation—a modal ya yielding new information—does not appear in other monolingual Spanish varieties?

2. Can we ind evidence that the duplicated ya (ya+[constituent]+ya) in Andean Spanish does not occur in monolingual varieties of Spanish? 3. knowing that the structures ya hay and ya ez verdad exist in Spanish, is there documentation of such combinations before the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492?

In order to respond to these questions, we will consult the davies (2002-) cor-pus, targeting speciically the oral data from the habla culta (‘educated speech’) of main cities in the Hispanic world (Caracas, San José, La Havana, Quito, Lima, Santiago de Chile, Buenos Aires, etc.) where Spanish is considered to be the most ‘standard’. The fact that the data come from mostly monolingual varieties serves

Adverbial ya

Adverbial 76% (76)

Discursive ya

discursive 14% (14)

Modal ya

New Information 0%

Old Information non-comparative 2% (2)

Old information comparative/contrast 6% (6)

Non-factual information 2% (2)

to accomplish step 3 of the analysis which focuses on compiling evidence that can militate against contact-based explanations.

For the Basque Spanish innovation, we applied the baseline of pragmatic uses of ya (González 1999) to 100 cases of modal ya from the davies (2002-) corpus. Of the 100 cases analyzed, most uses of ya in monolingual varieties in the davies Corpus were cases of adverbial ya, followed by discursive and modal ya. For modal ya, we followed the analysis proposed by González (1999), inding that the majority of the cases were cases of old information in comparative/contrastive contexts. There were no cases of modal ya with new information which corrobo-rated that ya with new information is an innovation that only occurs in Basque Spanish. Below are two examples that illustrate the phenomenon:

(23) Se disculpó innecesariamente por las ausencias, ‘Ya ves que no falto cuando me es posible acudir.’

‘He apologized unnecessarily for his absences, “Ya you know that I do not fail to attend when it’s possible for me to come”.’ (Entrev -ista ABC: Fernandez Cid Antonio)

(24) Yame gustaría a mí que los arquitectos hiciesen casas así de - de

bonitas.

‘Ya I would like for the architects to do such beautiful houses.’

(España Oral: CCIE017A)

In the case of the common formulaic construction of ya ves, the ya is em-ployed to assert information and correct a possible inference from the interlocutor. In (23) the speaker is inferring that the interlocutor might think that ‘the speaker is always absent’, to which the speaker ‘brings the interlocutor back to the con -versation’ with ya ves, and subsequently corrects his incorrect inference, in this case the fact that ‘he does not miss when it is possible for him to come’ (Vigara Tauste 1992 quoted in González 1999:195). Another common formulaic use oc-curs before the conditional, in ya me gustaría. In this case, ya does not impart an adverbial value, as without it (ø me gustaría) ya is not pointing to a temporal reading. However, ya me gustaría does not express the same degree of afirmation and probability as ya ves, as the former occurs with a hypothetical, and therefore non-factual predicate.

Only 37 tokens of the ya+[constituent]+ya construction were found in the davies Corpus of a total of 39547 cases of ya (0.09%) in the oral corpus of the 20th century.2 Table 2 presents the number of cases of the double ya construction

separated by constituent type.

2 The search was carried out using the ‘collocate’ option of the Davies corpus which

Type of constituent Percentage(Token)

Verb Phrase 46% (17)

Adverb 19%(7)

Whole Clause 19% (7)

Noun Phrase 11%(4)

Prepositional Phrase 5% (2)

Total 100% (37)

tAble 2. Type of constituent in ya+[constituent]+ya in the davies Corpus (2002-).

The majority of the cases occurred with verb phrases (46%) and adverbs (19%):

(25) ¡No, no! desapareció el libro, porque yo después ya insistí ya, ¿no?, ya hice una cuestión formal, quería saber todo …

‘No, no! The book disappeared, because I later on ya insisted ya, no? I asked a formal question, I wanted to know everything … ’ (Habla Culta: Buenos Aires: M33B)

(26) Ya después ya... de muchos años de … de ejercicio profesional y de haberme metido en negocios y en cosas, me sentí obligado un poco a meterme en política …

‘Ya after ya… many years of … being a professional and hav-ing gone into business and thhav-ings, I felt a little obliged to get into politics … ’ (Habla Culta: Caracas: M6)

(27) Ya muchas de ellas ya se marcharon a la península a seguir la carrera de Farmacia o de Medicina …

‘Ya many of them ya left for the Peninsula to continue studying pharmacology or medicine … ’ (Habla Culta: Gran Canaria: 13)

ya’ (ya muchas de ellas ya) left to the Peninsula to start a career.

As the table shows, about half of the double ya constructions were found in the habla culta (educated speech) of Santiago de Chile (46%). The other cases were dispersed in different varieties around the Spanish-speaking world.

Region or City % of the total and Tokens

Santiago 46% (17)

Mexico 10.8% (4)

España 10.8% (4)

Havana 10.8% (4)

Lima 8% (3)

Buenos Aires 5% (2)

Caracas 2.7% (1)

Lima 2.7% (1)

Panamá 2.7% (1)

Total 100% (37)

tAble 3. Percentages of ya+[constituent]+ya in different varieties of Spanish according to the davies corpus (2002-).

The evidence in the davies corpus suggests that the double construction ya+[constituent]+ya is not a feature that only occurs in Andean Spanish, although we still need a corpus analysis of Andean Spanish to more accurately identify the types of constituents that the double construction tends to focalize.

For the Judeo-Spanish ya ay and ya ez verdad, we analyzed the diachronic distribution of both constructions in Peninsular Spanish (ya hay/ya es verdad) from the 15th to the 20th century, seen in Table 4.

Century % ya hay/ya ay/

total tokens of ya

% ya es verdad/ total tokens of ya

15th 0.10% (8/7850) 0.02 (2/7850)

16th 0.05% (21/31566) 0% (0/31566)

17th 0.08% (30/36667) 0.02 (1/36667)

18th 0.06% (11/18205) 0% (0/18205)

19th 0.06% (29/43657) 0% (0/43657)

20th 0.40% (159/39457) 0.01% (4/39457)

The two Judeo-Spanish constructions produced a relatively low number of tokens. The percentage of ya hay in the 15th century (0.1%) is lower than the 20th

century (0.4%). The uses of ya es verdad are even less common with only 0.01% appearing in the 20th century. Examples (28) and (29) are from the 15th century:

(28) Los puercos, de treze hembras que truxe, yahay tantos que andan bravos por las montañas …

‘The pigs, out of thirteen sows I brought, ya there are so many that roam wild in the mountains … ’ (Textos y documentos Completos de Cristóbal Colón, Christopher Columbus)

(29) Leemos que asant benjto fue rreuelado que yahay diablos que en espeçial son deputados de estoruar los eclesiasticos & de derramar les los coraçones …

‘We read that it was revealed to Saint Benito that ya there are dev-ils that specialize in exploiting the church and spilling their hearts … ’ (Libro de las donas, Fransescs Eiximenis)

According to Bello (1908) and Girón Alconchel (2011), Old Spanish, espe-cially during the 13th and 14th centuries, had a tendency to emphasize the afir

-mative value of propositions by using a modal ya or sí. This modal ya served to focalize the following constituent, especially with perfective tenses (Girón Alcon-chel 2011). This is the case for both examples above. In (28) ya hay focalizes the existence of ‘wild pigs’, whereas in (29) it is employed to focalize ‘the devils’. In (30) and (31), which are from the 20th century, notice how the speaker uses ya hay

to focalize the afirmative value of the proposition.

(30) Naturalmente, se ha granjeado enemigos por todas partes y yahay quien ha pedido su cabeza …

‘Naturally, he has won enemies everywhere and ya there have

even been those who have asked for his head … ’(Entrevista ABC:

Mataboch, Joan)

(31) Yahay una serie de artistas que dependen absolutamente de determinados teóricos

‘Ya there is a series of artists who depend completely on certain theoreticians … ’ (Entrevista ABC: Pedro Corral)

his head for saying those things. Without ya hay in (31), the reading would be neutral, whereas when it is included, it intensiies the speaker’s commitment to the truth value of the statement, ‘There are artists that depend on certain theoreti-cians’.

In conclusion, we can observe, with the exception of Basque Spanish ya with new information, militating evidence against the contact-induced hypothesis. In the case of ya+[constituent]+ya we ind that it is indeed used in other monolin -gual varieties and with a range of different constituents. In the case of ya ay/ya ez verdad we also discover that it was present before the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews in the 15th century, albeit relatively infrequent (i.e. only 0.10 % of all ya

tokens).

4.

the three

linguistic coMMunities: steP 4. The last step in the

anal-ysis centers on identifying the correlation between the level of contact and bilin-gualism in the community and the relative frequency of ya-constructions. Before we analyze the distribution of ya in our corpora of the three varieties, we provide a brief overview of the linguistic communities based on four extralinguistic factors: (1) intensity of contact, (2) length of contact, (3) status of the languages in the community, and (4) size of the language community (Thomason 2001, Winford 2003). A sociohistorical description of each linguistic community will help us to situate how extralinguistic factors affect the use of this feature.4.1.

bAsQue

And sPAnish in the bAsQue AutonoMous coMMu-nity. As a pre-Indo-European language, Basque has been in contact with Spanish

in the Iberian Peninsula for centuries, dating back to the formative stages of the Spanish language itself (Tovar 1959). According to the most recent data on the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC), 49% of its 2.1 million inhabitants are Spanish monolinguals, 30% are bilinguals, and 21% are passive bilinguals (Eusko Jaurlaritza 2011). The distribution of Basque continues to be spatially marked with a high percentage of bilinguals (between 50% and 70%) in many towns and a low percentage (4%-11%) in the cities. due to the strong Basque nationalist movement, the majority of the population in the Basque Country supports lan-guage revitalization efforts and has positive attitudes towards those who speak the language and want to learn it (Eusko Ikaskuntza 2007).3 The data in this study3 The Basque Autonomous Community has experienced a relatively recent rise in the

come from two different oral corpora of semi-structured interviews gathered by Ciriza (2009) in two different locations: Bilbao (10 speakers) and Bermeo (6 speakers). In our corpus from Bilbao, all of the speakers were Spanish dominant, although they had passive academic knowledge of the Basque language. In Ber-meo, all the speakers were balanced bilinguals although they speak Basque more often than Spanish on a daily basis.

According to the latest surveys Bilbao presents 25% bilingualism and 22% passive bilingualism (Eusko Jaurlaritza 2011). Even though the number of euskal-dunberris has grown in the last 20 years in Bilbao, longitudinal studies show that the use of Basque is infrequent in the city despite the fact that a large percentage of the population has academic knowledge of the language. Concretely, studies show that only 3.2% of the population in Bilbao actively uses Basque in their public interactions with their friends, family, and in the streets (Soziolinguistika klusterra 2011). Bermeo is a relatively small community (17,144 inhabitants) 30 kilometers east of Bilbao on the Atlantic coast. In the Busturialdea region where Bermeo is located, bilingualism is high, rising to 76%, passive bilingualism is at 12% and only 13% are Spanish monolinguals (Eusko Jaurlaritza 2011). In relation to the use of Basque on the street, the most recent sociolinguistic census indicates that the use of Basque among speakers 65 and older is at 60% whereas among the 25-64 age group it is at 30% (Bermeoko Udala 2011). These contrasting linguistic landscapes are essential to determine if the level of bilingualism affects the dif-fusion of the innovative use of modal ya, or whether it has diffused throughout several communities with similar language contact dynamics.

4.2.

QuechuA And AndeAn sPAnish in ecuAdor

. The Quechua

lan-guage is an Amerindian lanlan-guage autochthonous to South America and spoken by an estimated 13 million speakers. It can be found primarily in Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia and peripherally in northern Chile and Argentina, southern Colombia, and the Amazonian region of western Brazil (Cerrón-Palomino 1987). Although Que-chua and Spanish are not genetically related, modern-day varieties in the Andean region share a considerable amount of vocabulary and some structural features as a result of language contact that began during 16th century Spanish colonialism.Historically, Quechua monolingualism has been conined to the rural regions of the central provinces of the Andes, especially among isolated communities near the páramos ‘high-altitude pastures that are typically not arable’. These commu -nities were characterized by not having access to education or to the commercial markets in the regional cities.

For the past 50-70 years, long-term migration to Spanish-speaking cities has

coexisted with more temporary and seasonal movements. Seasonal migration is still commonplace and normally occurs among younger members of indigenous households who want to save money or complement the income they earn from agriculture. Along with migration, the wider coverage of the school system in the highlands has changed the linguistic landscape of the Ecuadorian Andes by intro-ducing the Spanish language to new and varied domains. Currently, the central region of the Ecuadorian Andes where the ieldwork reported on here was con -ducted has several Spanish-Quechua bilingual communities in which the choice of one language over the other varies depending on the situation (Haboud 2003), a practice that is slowly losing ground to Spanish monolingualism. In their study of linguistic attitudes in the Ecuadorian Andes, ridstedt and Aronsson (2002) found that speakers’ practices are structured along a generational scale of language use: elders tend to be dominant in Quechua, most middle-aged adults are Spanish-Quechua bilinguals, and the youth are monolingual Spanish speakers employing only a handful of formulaic utterances in Quechua.

The Andean Spanish data for the current study were collected between 2006 and 2010 in the Ecuadorian cities of Latacunga, Salcedo, and Ambato as well as in some rural communities near Salcedo and Latacunga. All of the speakers were Spanish bilinguals and despite having grown up around Quechua-speaking family members, they described themselves as Spanish dominant. The recordings from which the Andean Spanish was transcribed were made during weekly asambleas ‘town hall meetings’ where speakers expressed their ideas pub -licly and often passionately. Many of these recordings and subsequent transcrip-tions are accompanied by ield notes that the researcher (Shappeck) wrote while living and traveling in the region.

and ultimately language endangerment occurred after the founding of the Turkish republic in 1929, when the new government imposed a series of pro-Turkish na-tionalistic language policies including compulsory education in Turkish and the banning of foreign language schools (Benbassa & rodrigue 2000:101-04, Sachar 1994:101-02). decades later, during the Second World War, Nazi invasions and occupations resulted in the decimation of entire Jewish populations in the Balkan and post-Ottoman homelands. Nationalistic language campaigns, constant migra-tion to Western Europe, the United States, Latin America, and eventually Israel, led to the loss of linguistic domains and a reduced population of speakers. The language is in a precarious state: it is spoken by about 110,000 speakers (Lewis et al. 2014), none of which are monolingual, and most of which are 60 years of age or older. The dispersed communities have not managed a successful intergenera-tional transmission and all speakers display language shift in favor of the oficial languages such as Turkish and English.

of Spanish that has undergone at least ive centuries of bilingualism with Turkish, and it was spoken by a very small minority in an urban setting. The authors read Luria’s compilation, which consisted of about 23 folktales, and counted and clas -siied every instance of ya.

The second set of data is derived from sociolinguistic interviews conducted in Istanbul in 2007 and in the Prince Islands (in the Istanbul Metropolitan Area) in 2009 (compiled in romero 2009). data from these interviews have also been ana-lyzed in romero (2011a), romero (2011b), and romero (2012). Although these two geographical areas are separated, thanks to modern advances in transporta-tion, the island and mainland communities have merged and represent one speech community. This set of data is more modern than that of Monastir and represents a community with a higher degree of ‘Turkiication’, as Turkish-Spanish bilingual -ism is the result of a century of nationalistic language campaigns. There are no Judeo-Spanish monolinguals in Istanbul; most speakers are 60 years old or older, and the language is spoken at home, to communicate with the older generation, and sometimes as a code language (Romero 2012:65-66, 92-99). Istanbul’s tiny Sephardic community is comprised of a minority of 25,000 speakers, roughly 0.16% of the city’s population. Although there are current efforts to revitalize the language, which many see as a cultural asset and a marker of Jewish identity, negative attitudes also exist, and many Sephardim view their dialect as jargon, a mixed language, and ‘not real Spanish’ (Romero 2012:80). The different levels of Turkish bilingualism in each community can help identify if such conditions play a role in the treatment of modal ya as a change through language contact.

5.

uses

oF ModAl ya in bAsQue sPAnish, AndeAn sPAnish AndJ

udeo-s

PAnish.

5.1.

bAsQue sPAnish dAtA

. Our Basque Spanish corpus contains 83 cases

of ya from the low-contact area of Bilbao and 81 from the high contact area of Bermeo. The data were irst separated following the three main semantic catego -ries: adverbial, modal and discursive. Bilbao presented 16 cases of modal ya and Bermeo 27. The cases of modal ya were further separated following González’s (1999) taxonomies.Modal ya Bilbao (16/83) Bermeo (27/81)

New Information 19% (3) 33% (9)

Old Information non-comparative 37% (6) 44% (12) Old information comparative/contrast 25% (4) 19% (5)

Non-factual information 19% (3) 4% (1)

The majority of modal ya examples in Basque Spanish appear with factual information, speciically with predicates that do not compare and contrast old information. The majority of the innovative cases (new information) occur in the high contact area of Bermeo.

(32) Mira a la gente se le conocía por sus hechos / … / siempre ya ha

habido, ha habido gente que era español y ha muerto por el

nacio-nalismo vasco y era española.

‘Look, people used to be known for their actions / … / there have

ya always been, there have been people that were Spanish and

they have died for Basque nationalism and they were Spanish.’ (Ci -riza 2009)

The Bermeo speaker in (32) is describing how Basque nationalists used to live during Franco’s 36-year dictatorship. He comments on the fact that during his control of government, people in the small town of Bermeo knew who the Basque nationalists were by their actions and behavior. Later, there is a change in topic and the speaker adds that there were also (non-Basque) Spaniards who died for Basque nationalism during the Franco era. The presence of ya in siempre ya ha habido ‘there have ya always been’ draws attention to the afirmation that ‘there have been Basque nationalists of Spanish origin’ which constitutes new informa -tion in the discourse. González also notices how ya can appear with adverbs like siempre or nunca, reinforcing the afirmation as well as the break in the temporal/ aspectual reading of ya since the habitual meaning of siempre is incompatible with the aspectual meaning of temporal ya (1999:167). In Bilbao, the innovation was mostly in the form of yes/no questions and afirmative responses:

(33) ¿Ya sabe pasarlo bien aita, eh? Que yo le conozco. ¡Pero bien que se lo pasa, aita!

‘Ya Dad does know how to have fun, eh? I know him. Now he

knows how to have fun!’ (Ciriza 2009)

In (33), ya does not serve as a temporal marker as the speaker is not asking whether the father already knows how to have fun; this ya is drawing attention to an afirmative fact that the father ‘does know how to have fun’ as the speaker has observed. While the speaker in (33) is from the low contact area of Bilbao, those in (34) are from Bermeo. The mother (speaker A) is talking to her daughter about the plans she has for the next day.

(34) B: ¿Ya hay caldo en Casa Pedro?

B: ‘Ya is there soup at Casa Pedro?’

A: ‘Ya there is, ya there is, do not worry about that.’ (Ciriza 2009)

In the irst utterance, ya serves to preface the daughter’s question of whether there is soup. This ya does not have a temporal value, as it is not asking about whether the soup is ready, since it is the irst time the topic emerges in the conver -sation. Similar to Basque ba-, this ya introduces new information in the form of a yes/no question which serves to ask about the existence of soup at the bar, Casa Pedro. The mother subsequently responds by bringing attention to the afirmation with ya hay ‘ya there is’. Basque Spanish ya mirrors the pragmatic function of Basque ba- by emphasizing new information. Furthermore, there is also structural similarity between Basque ba- and Spanish ya (table 6).

Placement Temporal Discursive Modal

ya + V 40% (38) 46% (12) 100% (39)

V+ ya 60% (57) 53% (14) 0% (0)

Total 95 26 39

tAble 6. distribution of the functions of ya (adverbial, modal and temporal) by verbal placement in Basque Spanish.

As Table 6 illustrates, unlike adverbial and discursive ya which appears both pre- and post-verbally, our modal ya can only occur pre-verbally in Basque Span-ish. We suspect that it is the obligatory preverbal position of ba- which is leading to ix modal ya to the preverbal position.

A

PPlyingM

ougeon et Al.’

s(2005)

Methodology tob

AsQuesPAnish ya

.

The Basque preix ba- and Spanish ya have a similar afirmative function and can be considered to be equivalent features. The use of afirma -tive ya in Basque Spanish reaches beyond the uses of modal afirmative ya in monolingual Spanish varieties as it also serves to emphasize new information (González 1999). Therefore, we cannot consider it a case of analogy or another type of internal process. The use of ya with new information in Basque Spanish is a case of pragmatic complexiication understood as the incorporation of new discursive functions to a preverbal modal ya (cf. Trudgill 2011). This type of ya is not accounted for in other Spanish varieties. With regard to other Basque Spanish varieties, the literature suggests that the modal ya is also found in other bilingual areas of the Basque Country, speciically coastal and inland areas (Altube 1929, González 1999).there are differences in these areas: in the high contact area of Bermeo we ind not only a higher use of ya with ‘new information’, but also with more types of verbs (traer ‘to bring’; comprar ‘to buy’; leer ‘to read’); conversely, in Bilbao, the scope of application of this innovation is still restricted to speciic verbs, spe -ciically haber (auxiliary ‘to have’) and saber (‘to know’). To summarize, strong empirical evidence exists that the modal ya indicating new information is an in-novation, both structural and pragmatic, which can be attributed to contact with Basque. Structurally, modal ya in Basque Spanish ixes its position before the verb paralleling the structure of Basque ba- (González 1999). Pragmatically, ya mirrors the pragmatic function of Basque ba- by emphasizing new information. Moreover, covert-induced change is supported by the data as Bermeo informants exhibited ya in more preverbal positions, even in adverbial and discursive uses.

5.2.

A

ndeAns

PAnishdAtA. In the lower contact area of Quito, we do not

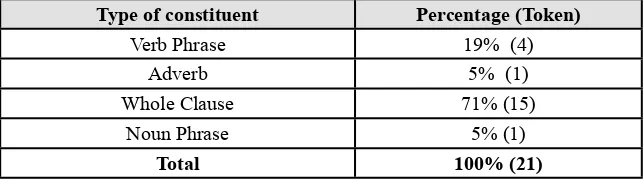

ind cases of the ya+[constituent]+ya structure in the 103 tokens of ya in the da-vies corpus. In order to supplement our corpus, we also analyzed the PrESEEA corpus (Project for the Sociolinguistic Study of Spanish from Spain and America), speciically the oral data of the Spanish variety spoken in Lima (since cases of the double construction have also been attested in Peru). We located only 3 cases of the construction out of 467 cases (0.67%). Conversely, in the higher-contact area of Cotopaxi, we found 21 instances out of the total 128 cases documented (16%). Table 7 shows the cases by constituent.Type of constituent Percentage (Token)

Verb Phrase 19% (4)

Adverb 5% (1)

Whole Clause 71% (15)

Noun Phrase 5% (1)

Total 100% (21)

tAble 7. Type of constituent in ya+[constituent]+ya in high-contact Andean Spanish (Salcedo).

with the town members about the fact that a much needed tractor which was sup-posed to be delivered from Quito has not arrived to town yet.

(35) Él dice que ↑ya está depositado en el banco ya↓. Sobre sí en

verdad está depositado o no, el comisionado dijo, ‘Que sí está depositado ya.’

‘He says that ya it’s deposited in the bank ya. Now whether it’s

actuall deposited or not, the commissioner said, “Yes, it’s deposited ya”.’

The community members repeatedly ask about the money that was set aside for the collective use of a tractor to plow the ields. They want to know whether it still appears in their bank account since they fear it has been stolen or misused. In response to this continued questioning, the president of the asamblea reassures everyone that the commissioner veriied the safeguarding of the money. It is at this point that the president uses the double ya construction to reafirm to the audi -ence that the money was secured. The duplication of ya in ya está depositado ya (‘ya it is deposited in the bank ya’) has a modal function which intersubjectively serves to assert to the audience that the money had already been deposited. The utterance adopts a particular prosodic contour: rising pitch in the irst ya which is maintained until the second ya (indicated in the above example with arrows).

(36) Estudio técnico yo tenía hace tres semanas. ↑Ya lo tenía yo ya

compañeros↓. Ahora nos lo están pidiendo de nuevo.

‘I had the technical study three weeks ago. Ya I had it ya, folks. Now they are asking us for it again.’

In (36), the speaker explains to the audience that he had already had the tech-nical study carried out three weeks prior, then reiterates this information with the second ya which emphasizes the fact that ‘he had it’.

(37) Sí, comunicaron pero ↑ya ha sido tarde ya↓ entonces no traen el

tractor han dicho.

‘yes, they communicated it (to us), but ya it was too late ya. So then they didn’t bring the tractor, they said.’

(38) No trabajo, ↑ya no trabajo yo ya↓ no puedo trabajar / de aquicito

una hija por acá siembra otra hija al otro lado vive …

‘No, I don’t work. Ya I don’t work anymore ya. I can’t work. One

of my daughters plants the crops here, and my other daughter lives over there … ’

The double construction is also used to emphasize a whole predicate as in (38) where the interviewer asks the informant whether she still works in the ha-cienda. Her irst utterance simply negates the proposition that she works. Then she reiterates the information with the double-ya construction Ya no trabajo yo ya (‘Ya I don’t work anymore ya’) which places greater emphasis on the predicate.

(39) No entiendo por qué se queja usted. ↑Ya no es culpa de nadie ya↓. ya así habían dado la tierra y no es culpa [de nadie].

‘I don’t understand why you complain. Ya it’s not anybody’s fault ya. Ya they had given the land and it’s not [anybody’s] fault.’

reinforcement of perfectivity occurs especially in the past tense, concretely with events in the preterit and present perfect; however, this reinforcement also occurs with other elements such as adverbs, as in (40).

(40) Mi padre murió ↑ya mayor ya↓ con 74 años. ‘My father died ya at an old age ya at 74.’

In this case we can see how the focus is still on the perfectivity of the event, that is, the fact that the speaker’s father has already died. However, it is the adjec -tive that is placed in the foreground with the double-ya construction.

16% of the time, points to the fact that the double construction in Andean Spanish is a case of a covert-induced innovation. Moreover, if we consider that the type of constituent in which the double construction tends to occur, that is whole clauses, it is even less frequent, occurring only 0.001% of the time in the davies Corpus (2002-), in comparison with 11% in the Salcedo corpus.

In terms of step 4, the relatively high frequency of duplicated ya in Salcedo as well as other high contact areas in other studies (c.f. Lee 1997, Feke 2004), versus the lower frequencies in low contact areas (Quito and Lima), supports the argument that the feature has not reached monolingual areas and still forms part of the speech of bilinguals in high contact areas. To conclude, a more frequent use of the double construction in Andean Spanish with different constituents has been triggered by (a) the functional similarity between Quechua -ña and Spanish ya, and (b) the fact that the double construction already exists in Spanish.

5.3.

Judeo-sPAnish dAtA

. The Monastir data are derived from the Luria

(1930) interviews. Given that these interviews appear as a searchable document, we tabulated every token of ya. The Istanbul data were obtained through two methods: the irst consisted of interviews initiated through open-topic samples; the second consisted of a translation exercise in which the interviewer read some sentences in Turkish (41) and the informant translated them orally into Judeo-Spanish (42).(41) Interviewer: Bu kadının uzgun olduğuna inanıyorum [Turkish] ‘I believe this woman is sad.’

(42) Informant: Esta mujer ya estó entendiendo ke está uzdjunlía [Judeo-Spanish]

‘I believe ya this woman is sad.’

Old Spanish

Compare, for instance, the ya ay combination at 0.1% in Old Spanish to the 5% in Monastir and 28% in Istanbul. The differences between Monastir and Istan-bul are related to the fact that there is a higher degree of contact with Turkish in Istanbul than in Monastir. Conversely, for ya ez verdad, we found 9% in Monastir and 0% in Istanbul. In the Monastir data, we encountered sentences such as (43) and (44), where ya is used in combination with existential ay to place non-com-parative afirmative emphasis on the predicate.

The ya ay combination above focalizes the afirmation of the predicate that follows. The speaker uses ya ay to emphasize the certainty of the subsequent predicate. For instance, in (43) the speaker knows or has seen the ‘man who can appraise the horse’. In (44) s/he asserts the existence of this ‘type of duck.’ Al -though the description of such a creature in (44) depicts it as magical and surreal, the use of ya ay underscores the speaker’s commitment to the veracity of the proposition (i.e. that it exists). The same combination is found in the data from Istanbul and the Prince Islands:

(45) Ya ay munchos luguares para ir ayí kon los hóvenes, por muje-dades, munchos kafés i luguares.

the crowds, lot of coffee shops and places.’

(46) En sivdad ya ay arvolikos, arvolés chikos. ‘In the city, ya there are little trees, small trees.’

Again, the speaker’s use of ya ay serves to establish his/her relationship to the source of knowledge that would afirm the truth of the proposition. In (45), the speaker is emphasizing that these places exist and even that s/he has been there or has seen them. Likewise in (46), the speaker knows conidently that these trees are in the city because s/he has been aware of their presence. The function of ya ay in (43) to (46) resembles that of an evidential construction because it afirms or asserts the existence of its predicate. This function is parallel to the diachronic and retrospective evidential functions of the Turkish sufix –(I)mIş which also evalu-ates and emphasizes the truth of predicevalu-ates. However, whether or not this function of ya ay is due to Turkish inluence will be discussed in the following section.

A similar combination was found only in the Monastir data, ya + ez verdad ‘ya it is the truth’, with the same function as ya ay:

(47) Estu ki m’istás kuntandu ya ez verdad. D’ondi mi lu dipreves ki

ez mintires?

‘This thing you are telling me yait’s the truth. How can you prove that it’s lies?’

(48) Ya ez vardá ki ya istuvitis antiz dil egumen.

‘Ya it’s true that you were already before the abbot.’

In (47), the speaker emphasizes his/her afirmation of a previous comment. In fact, s/he is so sure of its truth value that s/he even encourages the listener to prove otherwise. In (48), the speaker is equally conident about the predicate and has irst-hand knowledge on the order of events (irst the listener was there, then the abbot came). Within the pragmatic domains of modal ya delineated by González (1999), both constructions are employed to emphasize already evoked informa-tion without comparing or contrasting it. The ya construcinforma-tions serve to frame the fact that the speaker shows control of the knowledge about the truth value of the information. Ya ay/ya ez verdad act as grammaticalized units intensifying the de-gree of conidence that the speaker transmits, an aspect that is closely related to the evidentiality system of Turkish.

monolingual Spanish varieties, we not only found instances of ya (h)ay in the davies (2002-) corpus (see Table 3), but we also discovered that this structure was prevalent in Old Spanish from the XIII-XV centuries. According to Bello (1908:105-06), Old Spanish had a tendency to emphasize the afirmative value of propositions, and so ya ay/ya ez verdad could be analogous structures in Ju-deo-Spanish which originated in the Peninsula before the Expulsion and the sub-sequent contact with Turkish. Based on this information, our irst hypothesis is that both structures are archaisms that have remained in Judeo-Spanish from Old Spanish.

However, following step 3, an alternative hypothesis arises. According to Mougeon et al. (2005), when two distant varieties of the target language which (a) are in contact with the same source language but (b) in distinct geographic locations share the same linguistic feature, this lends support to the position that the feature emerged through contact. In our case, we have two geographically distant varieties of Judeo-Spanish which have emerged during different histori-cal periods: Monastir from 1926-1927 and Istanbul from 2007-2009. From this reading, the use of ya ay/ya ez verdad can be argued to have emerged through Turkish/Judeo-Spanish bilingual communities since both structures are employed with pragmatic meanings that are similar to the ones in Turkish. However, more quantitative and pragmatic analysis is needed to corroborate the contact-induced position.

Applying step 4, we focus on the fact that Monastir has experienced less contact with Turkish than Istanbul for several reasons. First, Monastir (modern Bitola in the republic of Macedonia) is located in the Balkans and distant from Turkey proper. Second, bilingualism between Judeo-Spanish and Turkish appears to have occurred mostly among the men in the community, and therefore any di-rect Turkish inluence must have been incorporated gradually into Judeo-Spanish. Third, upon the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire in 1912, Turkish inlu -ence waned in Monastir, as Turks ceased to be the majority and many moved out of the Balkans. On the other hand, contact between Judeo-Spanish and Turkish in Istanbul occurs in the entire Sephardic community, men and women of all ages speak Turkish, which has been imposed as the oficial language for over a century.

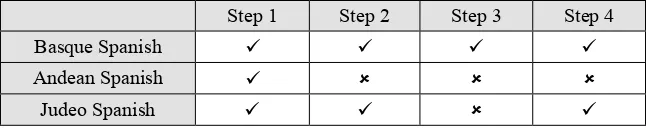

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

Basque Spanish

Andean Spanish

Judeo Spanish

tAble 9. Measuring the three Spanish varieties for contact-induced change.

Table 9 summarizes the indings on steps 1-4 in our three contact variet -ies. The only variety that reads afirmatively for all four steps is that of Basque Spanish ya. The use of ya with new information in preverbal position is linked to the Basque afirmative preix ba- and has emerged through contact with Basque-Spanish bilinguals (González 1999). Conversely, in Andean Basque-Spanish, the use of duplicated ya to emphasize perfectivity cannot be considered an innovation in the traditional sense given that Spanish monolingual varieties also employ the double construction to emphasize perfectivity and with different constituents (from ad-verbs and ad-verbs, to whole clauses), as attested in the davies corpus. Therefore, we argue that duplicated ya does not fulill step 2 since it can be found in non-contact varieties of Spanish and does not meet the criterion of step 4 as it is lim-ited to Quechua-Spanish bilingual speech communities. duplicated ya is a covert-induced innovation—experiencing an increased use of an already existing feature in Spanish—but not qualitative change.

The case of the ya ay and ya ez verdad constructions in Judeo-Spanish is more complex and cannot be attested in a straightforward manner. What is veriiable is an increase in the use of these constructions in two varieties of Judeo-Spanish, suggesting that they have acquired new pragmatic functions. In this case, we have linked the use ya ay/ya ez verdad with the pragmatic values of evidentiality in Turkish to emphasize the truth of a proposition. However, since the constructions already exist in Old Spanish, we cannot conidently postulate that this implies a qualitative change in the use of a feature, but rather it constitutes a covert-induced change. An alternative hypothesis would state that the evidential readings of ya have been inluenced solely through contact given that two varieties of Judeo-Spanish in contact with Turkish have these structures. However, more evidence and a larger pragmatic and quantitative analysis are needed to corroborate this claim.