Introduction

A cit y is a collection of buildings and people (Kostof 1992). Nas (1986, in Zaidulfar 2002) list s À ve major as-pect s to a cit y: a man- made material environment , a production centre, social communities, cultural com-munities, and a controlled societ y. Hence, it can be deduced that the cit y is shaped by physical aspect s of space and by the communit y. Furthermore, according to Widodo (2004), architecture (and thus the urban space) can also be observed through dif ferent time frames or historical periods within the process of transformation. Within this transformation, cert ain element s of perma-nence can be identiÀ ed which preserve the memory of the identit y of places and event s. At each level, there are compelling monument s among the ordinary fabric and the qualit y of permanence determines the features of transformation.

The m odern concept of a cit y assert s t hat urban spaces consist of public and private spat ial organiza-t ions where people have equal conceporganiza-t ions of urban-it y and share the sam e goal, of living together (San-toso 2006). According to M adanipour (1996), we can t ranslate and interpret social organizat ion, polit ics and space within a cit y through the dist inct ion bet ween public and privat e. The organizat ion of public and pri-vate urban spaces is a manifest at ion of the system of values adopted by t he societ y. In t his context t he pro-cess of learning to be a cit izen begins when t he people in the cit y concur to regulate the use of comm unal space. Through public space we can obser ve the char-acter of the cit y’s citizens and the expression of urban ident it y.

From the perspective of urban design, the process of the formation of a cit y can be observed by focusing on public space. Public space is now understood to feature the following characteristics (Ikaputra 2004; Lang 2005; Purwanto 2004; Danisworo 2004; Gavent a 2006; Carr et al. 1992):

1. Space in which people interact and conduct vari-ous activities in a shared and common environment , in-cluding social interaction as well as political, economical and cultural activities.

2. Space that is owned, managed and controlled collectively – both by public and private institutions – and is dedicated to the interest s and needs of the public.

3. Space that is open and is visually and physically accessible to all without exception.

4. Space where the communit y has a free choice of activities.

In the meantime, cit y aspect s of character and iden-tit y have become a powerful issue in an international context . The idealization of globalization around the world has prompted changes in economic systems, the Á ow of information and numerous other areas. Global economic systems for example encourage the unifor-mit y of commodities and of identit y. Thus it has become common to À nd similar cities throughout the world.

The cit y of Yogyakart a, located in the heartland of the Indonesian island of Java, has the unique abilit y to maint ain a distinctive identit y and atmosphere. Yogya-kart a features a number of characteristics, such as being the last kingdom of M at aram, the cit y of revolution, a cit y of education, a cultural cit y and a cit y of tourism. These at tributes indicate the number of potential as-pect s that drive the changes in the cit y, not only physi-cally but also concerning it s identit y and character.

This article will at tempt to explore the identit y and the character of the cit y of Yogyakarta through its public space. On the one hand, its historical roots will be exam-ined, and on the other hand, contemporary issues that are expressed in the public space of the cit y will be exam-ined to obtain the latest facts on the status of the cit y’s public space. By tracking the history of the formation of urban public space and through observing contemporary case studies in urban public space, the formation of the cit y's identit y and character and the inÁ uence of its citi-zens on transformations that occur will be examined.

THE TRANSFORMATION OF URBAN PUBLIC SPACE

IN YOGYAKARTA

A Search for Specific Identity & Character

by Rony Gunawan Sunaryo

abNindyo Soewarno

b, Ikaputra

b, Bakti Setiawan

bUrban Morphology

According to Rossi (1982), a cit y is a “collective ur-ban artefact ”, a collective work of art that is constructed through time and is rooted in a dwelling and building culture, and a manifest ation of social life. The cit y ex-presses the link bet ween the individual builder or dwell-er and the communit y. The cit y grows ovdwell-er time in the course of it s realization. Some original themes persist or are modiÀ ed. Durable material keeps the traces of previ-ous conditions and changes. The cit y is a rich archive of complex set tlement history. To underst and the process-es that shape a cit y, it is crucial to underst and the cit y’s history of formation. This history can be traced through historical element s within a cit y. The most comprehen-sive approach to this study is to underst and the mor-phology of a cit y. This mormor-phology of the cit y cannot be separated from the cit y’s physical appearance, which is mainly formed by the physical conditions and by the interaction with a dynamic economic societ y. The mor-phology can be understood by studying the develop-ment of physical form in urban areas, which is not only associated with the building and the architecture, but also with the circulatory system, open space and urban infrastructure – especially roads – as a major shaper of spatial structures. The physical appearance of a cit y is a visual manifest ation that partially result s from the inter-action and mutual inÁ uence of the critical component s mentioned above (Allain 2004, in Widodo 2004).

In every historical period, architecture can be per-ceived as a tot alit y of at least three main layers on every scale: a morphological layer (physical, formal), a socio-logical layer (activit y, functional, anthropometrical), and a philosophical layer (meaning, symbolical, mythologi-cal). M orphological articulation is directly related to the inhabit ant s’ sociological activities and to the ascription of meaning. The architecture of a cit y deals with this multi- dimensional matrix. The physical and spatial form of the cit y is the product of it s inhabit ant s and the mani-fest ation of their culture over time. To get a holistic un-derst anding of the history and morphology of a cit y, it should be studied in terms of it s synchronic (across dif-ferent layers) and diachronic (across historical periods) aspect s. A hermeneutic approach should be employed, incorporating multidisciplinary analysis such as anthro-pology, archaeology, sociology, economy, geography, history, etc. Therefore a collaborative and interdisciplin-ary approach is essential.

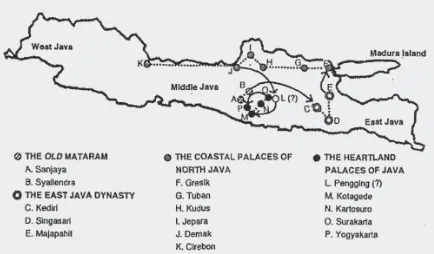

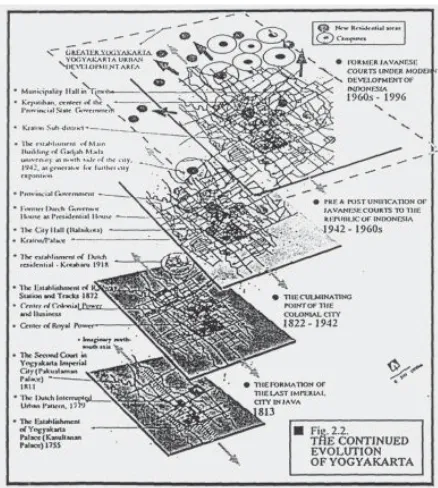

In terms of the major event s that af fected the politi-cal, economic, cultural, social and ideological develop-ment s, the history of the formation of Javanese cities

can be divided into À ve periods: the Period of Hindu M at aram (7t h-10t h centuries), the Period of the Eastern

Agricultural Kingdom (10t h-15t h centuries), the Period of

the Coast al Empires (15t h-16t h centuries), the Period of

Is-lamic M at aram and Colonization (16t h-20t h centuries) and

the Period of the Republic (20t h century to the present).

The discussion in this paper will be based on these pe-riods. Present- day Yogyakart a was founded only about t wo and a half centuries ago, with the est ablishment of the Kingdom of Ngayogyakart a in the year 1756, during the period of Islamic M at aram and colonization. How-ever, brief reviews of the three previous periods will be given, so as to provide an overall picture of the histori-cal background of the formation of urban space in Java

(Fig. 1).

The Period of Hindu Mataram

The historical sources that could tell us about urban living and the set tlement in the Period of Hindu M at aram are limited, especially those that examine the existence of urban public space and communit y activities in it . Concept s of urban living and set tlement s in this period can only be based on the interpret ation by historians of limited physical artefact s. Wiryomartono (1995) st ates that Hindu and Buddhist ideologies had the biggest in-Á uences on the culture of this period. The terms for cit y and st ate, kuta and nagara, were derived from Sanskrit .

Kuta literally means “residential area that is protected by a round-shaped wall” (Wiryomartono 1995). Through Santoso’s (2008) study about the temples of Borobudur, Prambanan and the palace Ratu Boko we can infer some key concept s of this period: this already quite complex societ y interacted with other cultures at a regional level (Southeast Asia), technology and advanced construction management were used and the cult focused on moun-t ains/ plamoun-teaus as sacred places (Fig. 2).

The Period of the Eastern

Agricultural Kingdom

During the Period of the Eastern Agricultural King-dom, the civilization was dominated by the inÁ uence of the M ajapahit kingdom, whose capit al was located in Trowulan (near today’s M ojokerto). Ef fort s to recon-struct a map of the capit al of M ajapahit were based on the interpret ation of the book “Negarakert agama”, writ ten during that era, and on archaeological À nds in M ojokerto. The work of Pont (1923) and Pigeaud (1962) provide examples of such reconstructions (Santoso 2008).

The reconstruction by Pont in 1923 (Fig. 3) shows the central core of the M ajapahit kingdom: the Kraton (pal-ace) and the Kadharmadhyaksa (palace for the head of religious af fairs). The Alun- alun (town square) with it s side length of 900m (which according to Pont served as a parade ground), was on the north side of the centre and was surrounded by the most import ant buildings in the cit y. North of the Alun- alun was another major square, Bubat Square, with an area of approximately 1 km2. A 40m- wide road passed through the market

located opposite Bubat Square, connecting the centre of the kingdom with the main port of Canggu. The

Wanguntur, which was where the King received his sub-ject s, was situated on the south side of the Alun- alun. In addition to the public places, Pont ’s reconstruction also shows a court yard inside the main palace complex, which he describes as “general” and “open”. The char-acter of openness can also be seen in the absence of a fortress or walls around the cit y (Fig. 3).

Pigeaud’s clearer interpret ation from 1962 (Santoso 2008) st ates that the complex of M ajapahit consisted of a number of large and small residential unit s separated by open areas and wide boulevards. These areas were used for public purposes: they were market s, meeting

halls, cockÀ ghting arenas, viharas (Buddhist monaster-ies) and used for religious ceremonies and celebrations. Bubat Square, located in the northern, mainly residen-tial, area of the town, was the venue for a yearly celebra-tion by the common people, which the king also at tend-ed during the last few days. Wanguntur Square, in the area of the king’s palace, had a more sacred atmosphere and was used for coronation ceremonies or st ate recep-tions. Pigeaud’s reconstruction reveals to us that there was a separation bet ween royal rituals and the rituals of the common people.

Through several reconstructions, Santoso (2008) concluded that the basic principle underlying the con-cept of a cit y during the M ajapahit era was the principle of microcosmic dualities, which tended to accommodate all the st akeholders in the cit y. The spatial concept s were derived from the previous Period of Hindu M at aram. Whereas at the Buddhist temple of Borobudur, only the upper social class was entitled to enter the top level, in the cit y of M ajapahit , everyone was entitled to enter the centre of the town. This democratic concept is also re-Á ected by the absence of a wall encircling M ajapahit , which marks the close relationship bet ween the cit y and the surrounding region.

Fig. 2: Borobudur, built in t he 8t h century at t he top of an artiÀ cial

hill. (Source: Santoso 2008)

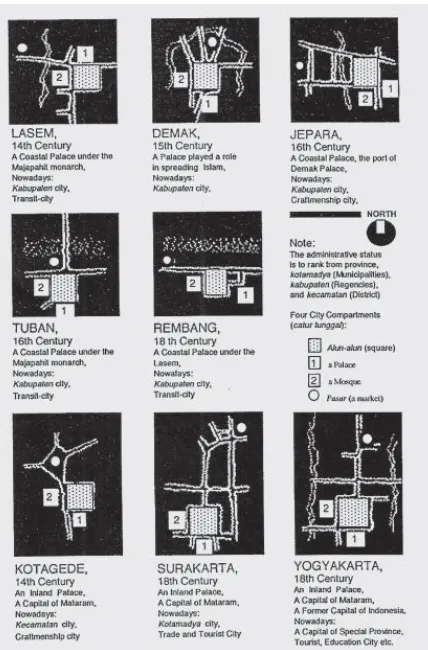

The Period of the Coastal Empires

Although the Period of the Coast al Empires was brief, it had a major impact on Java through the advent and massive growth of Islam. Af ter the fall of M ajapahit , the centres of power shif ted to the north coast of Java. Some of the cities, such as Demak, Jepara, Gresik and Surabaya became international trading port s or their port s served as strategic links to the cities of other is-lands. Ikaputra (1995) st ates that dif ferent nationalities in the cities est ablished residential set tlement s in the form of kampungs (villages). The kampungs were ex-clusive and defensive in character and the mastery of the harbour was a const ant source of conÁ ict bet ween them. The buildings of worship from this period, the great mosques, have remained as building artifact s to this day (Fig. 4).

Some element s of urban space from the Period of the Coast al Empires, such as the Kraton (Royal Palace), the Alun- alun (town square), the Great M osques, and the market s are still recognizable today. For example, the

Kraton remains the centre and the most sacred area in the cities to this day, just as the Alun- alun remains the venue for royal and religious rituals and celebrations of the people. Ikaputra (1995) notes that at least three major event s took place in the Alun- alun squares: Pepe

(the petition of individual voices to be heard by the king),

Watangan (tournament) and Garebeg (offering festival). It is worth noting that there is a banyan tree on the pal-ace squares as a landscape element and a symbol of the sanctit y of the squares. Lombard (1996) notes that the ritual transfer of the centre of a palace or a palace it self was always accompanied by the removal and planting of a banyan tree on the palace square. The Great M osques are always set near the palace square, and the Kauman

village can be found in the vicinit y of the mosque. The

Kauman villages are set tlement areas with an Islamic religious atmosphere, where the houses of the Kaum, religious leaders who preserve and protect the rituals of the Great M osque, are situated. During the time of the Coast al Empires, the market s became the centres of transactions bet ween merchant s. Widodo (2004) st ates that the existence of the market s in downtown is always related to the Pecinan (Chinatown). The concept of urban living in Java began to approach the present concept dur-ing the period of the Coast al Empires. Downtown spaces, such as the cit y market , could be accessed freely by the public. The mosques became public spaces in the M uslim cities. The Alun- alun, within cert ain limit s, became public places, especially during rituals. Even the Kraton could be accessed by commoners through the Pepe ritual.

The Period of Islamic Mataram

and Colonization

The Period of Islamic M at aram and Colonization was characterized by the return of the hegemony of an agrarian empire in the heartland of Java, the Kingdom of M at aram. The political scene of this period was also af fected by the intervention and the inÁ uence of the new colonial rulers, the Dutch. During this period, Pa-jang (1568), Kot agede (1586), Plered (1625-1677), Sura-kart a (1743) and YogyaSura-kart a (1756) became sult anates. The last t wo sult anates, with their distinct cultures, still exist today. In the Sult anate of Yogyakart a, the authori-ties play a signiÀ cant role in the political system to this day. Therefore, the discussion about the development of urban structures in Java will now be focused on the est ablishment of the cit y of Yogyakart a.

The cit y of Yogyakart a was founded by M angkubumi, who resented the close connection of his brother Paku Buwana II, the À rst ruler of Surakart a, with the Dutch.

Thus, in 1755, the Kingdom of M at aram was divided into the t wo kingdoms of Surakart a and Yogyakart a through the Gianti Test ament . In contrast to Surakart a, the Kra-ton (royal palace) of Yogyakart a also includes the living quarters for courtiers and princes. Overall the area cov-ers 23 ha of land, enclosed by a large wall of 1300 x 1800 metres in length. Five gates serve as entrances to the complex: t wo in the north, and one each in the east , west , and south.

In Yogyakart a the smaller Alun- alun Kidul (southern town square) is located within the walls of the fort , while the Alun- alun Lor (Fig. 5, A) represent s the interface be-t ween be-the courbe-t and be-the cibe-t y. The main axis of be-the cibe-t y is a wide road that extends from the north side of the

Alun- alun Lor to the north, where it ends at the Tugu M onument (Fig. 5, T). Along this road are a number of import ant structures, such as the pasar (market) (Fig. 5, M ); the kepatihan (Fig. 5, O), which served as the ad-ministrative centre of the kingdom; the kejaksaan (court building) (Fig.5, P) and shops owned by Chinese

mer-chant s and others (Fig. 5, N). On the western side of the road, right in front of the Dutch fort Vredeburg (Fig. 5, K) was the residence of the Dutch Resident (Fig. 5, J). According to Santoso (2008), only a few buildings were originally constructed along the North-South axis by the kings, but over time, the buildings gradually extended further to the east and to the west (Fig. 5).

In 1813, a treat y was signed bet ween Prince Nat aku-suma (who later took on the title of Paku Alam I) and M angkubumi (Sult an Hamengku Buwana I) which was similar in content to the agreement s bet ween Paku Bu-wana and M angkunegaran in Surakart a. The Paku Alam

(Fig. 5, Q) in Yogyakart a was deÀ ned as a residential area with a cert ain number of cacah (inhabit ant s) on the ter-ritory of the Negaragung (capit al) and was granted lung-guhan (land propert y right s).

The oldest set tlement s in Yogyakart a were the quar-ters allocated to the servant s, the palace guards, the builders, the blacksmiths, the musicians, the dancers, the government ofÀ cials, the princes and their follow-ers. An exceptional regional autonomy was granted to the areas of Paku Alaman and Secodiningratan (Fig. 5, H) (Santoso 2008), the lat ter being founded by Jing Sing, a leader of the Chinese people who is commonly known as Capt ain China. The Dutch set tlement s were also au-tonomous regions. Originally, the Dutch set tlement s were concentrated on the eastern side of the Vredeburg fort . In 1830, once Dutch rule had become more st able, new set tlement s were est ablished in the northeastern part of the cit y of Yogyakart a in an area which is today known as Kotabaru.

Meaning and Function of the Alun- alun

The Alun- alun Lor in Yogyakart a is a rect angular open space surrounded by banyan trees. A tot al of 64 banyan trees were planted, their locations correspond-ing to the buildcorrespond-ings surroundcorrespond-ing the square. The Alun-alun Lor measures approximately 300 x 265 metres and is covered with À ne sand. At the centre of the open space there are t wo banyan trees known as “Waringin -bracket s”, each enclosed by a quadrangular wooden fence. Both banyan trees symbolize the unit y and har-mony bet ween humans and the universe. This harhar-mony is called the concept of kawula- gusti (Kot a Yogyakart a 200 Tahun 1956, in Santoso 2008).

Everyone in the kingdom had the right to meet di-rectly with the king to ask for his judgment in case of a dispute. People wanting to meet the king were called

pepe. The pepe had to wear white clothing and head cov-erings and had to sit waiting bet ween the t wo banyan trees to be allowed to see the king. There, they had the

opportunit y to present their cases to the king, who was accompanied by his advisors. The king's decision on the set tlement of disputes was considered to be absolute and could not be contested (Pigeaud 1940, in Santoso 2008).

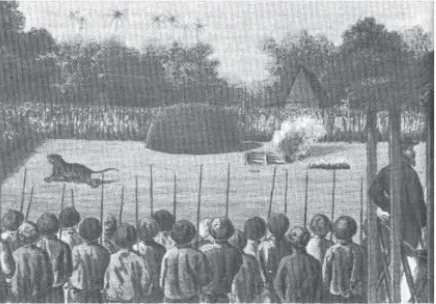

In the Alun- alun Lor, regular À ght s called rampogan

were held bet ween a bull and a tiger: these were always won by the bull. According to Santoso (2008), this ac-tivit y symbolized the victory of the cosmic forces over chaos, since in Java the bull (maesa) symbolizes the cos-mic forces, while the tiger (sima) is the symbol of chaos. During Dutch colonization, these À ght s took on a new meaning: the bull became the symbol of the Javanese people, who won against the Netherlands, symbolized by the tiger (Fig. 6).

In front of the mosque court yard are a pair of pavil-ions that hold t wo set s of gamelan (traditional musical instrument s) called Kyai Sekati and Nyai Sekati. Both set s of gamelan are played alternately, at the three religious ceremonies of Grebeg Maulud, Syawal and Gede (Kot a Yogyakart a 200 Tahun 1956, in Santoso 2008). The Gede, like most religious ceremonies in Java, originated in the pre- Islamic era. Af ter the advent of Islam, the ceremony was adapted to t ake place on the birthday of the Proph-et M uhammad, one of the key holy days in Islam.

The ceremonies mentioned above have been t aking place in the Alun- alun since the founding of the set tle-ment . The old Javanese beliefs were also incorporated into the design of the mosque, for example, in the form of the terraced pyramid roof, the division of space in the foyer and the space for worship, the plant s in the court-yard, as well as in it s close ties with the cemetery (Pige-aud 1940, in Santoso 2008). In accordance with Islamic beliefs, all ornament s depicting images of humans and animals have been removed.

Opposite the mosque, a building called a Pamong-gangan is used as a place for storing further gamelan

instrument s that are called monggang. This gamelan is said to be from the M ajapahit era. In earlier times, the

gamelan was played for an hour every Saturday before sunset . In addition, the monggang were played during a horse parade that was held on a regular basis until the British Colonial government restricted the keraton’s

milit ary power (Pigeaud 1940; Kot a Yogyakart a 200 Ta-hun 1956, in Santoso 2008). In former times, the Pamon-ggangan was also where tigers and other wild animals were kept in cages. Santoso (2008) suggest s that the

monggang gamelan was also played to accompany the

rampoganÀ ght s.

Along the sides of the square were the pekapalan, which served as lodging houses for high ofÀ cials who

came from out of town to at tend import ant celebrations. According to Pigeaud, the word pekapalan is derived from the word kempal, which means “to gather”. Other authors have argued that the word is derived from the word kapal meaning “horse boat ”, which was used by ofÀ cials to come to the capit al and to get around Yogya-kart a (Pigeaud 1940, p. 181).

Santoso (2008) concluded that the meaning and function of the square can be divided into three catego-ries:

1. The Alun- alun symbolizes the enforcement of a basic system of rules concerning a particular ter-ritory, but it also describes the enforcement of a system of power to create harmony bet ween the real world (microcosm) and the universe (the macrocosm).

2. The Alun- alun serves as a place for the celebra-tion of all import ant rituals or religious ceremo-nies. All celebrations and ceremonies are associ-ated with the implement ation of the laws of the universe in everyday life.

3. The Alun- alun serves as a place to demonstrate milit ary power, which has a profane character, and as a place to practice the sacred power of the ruler.

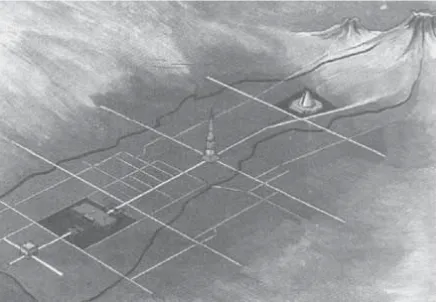

The relationship bet ween these three functions can be seen from the layout of each element of the buildings and the veget ation. No other cit y facilit y represent s in it s shape and meaning the views, religious life and phi-losophy of the Javanese people as clearly as the square. Santoso (2008) emphasizes that in Java, the art of build-ing is an instrument used to est ablish harmonious rela-tionships bet ween the cities and the universe, based on harmony bet ween the earth and the sky. Alignment is manifested through the arrangement of opposite pairs,

such as À re and water, earth and sun, sea and moun-t ains, sacred and profane. Unimoun-t y is a prerequisimoun-te for moun-the achievement of the salvation of human beings who live in a societ y. The way M angkubumi, the founder of Yo-gyakart a, put the main element s of an imaginary king-dom in a single axis that connect s M ount M erapi to the north of Yogyakart a with the sea to the south of Yogya-kart a can be seen as a clear manifest ation of an ef fort to form an alignment (Fig. 7).

The characteristics mentioned above for Yogyakart a dif fer from the characteristics of towns on the north coast of Java, where the layout of the cit y tends to be dominated by secular powers. This means that these cit-ies are not striving for a balance of power, but are look-ing for the peak of power by seeklook-ing freedom of trade and aiming to increase wealth in the cit y. According to Santoso (2008), this ideological factor is what makes the character of the coast al cities much more similar to Eu-ropean cities than Yogyakart a is.

The development of urban public space in this pe-riod cannot be separated from the Dutch colonial inÁ u-ence. Adishakti (1997) mentions that the Dutch ef fort to ret ain power in Java manifested it self in the est ab-lishment of the Vredeburg fort on the north side of the

Alun- alun in 1790. Later, a residence of the Dutch au-thorities was est ablished on the west side of the fort as a support . British inÁ uence also shaped the structure of urban space. During the British reign of St amford RafÁ es (1812), prince Notokusumo was rewarded with the posi-tion of ruler of the new heredit ary principalit y Pakuala-man and received the title Sri PakualaPakuala-man I, af ter he had helped to calm the conÁ ict bet ween the British and Sult an Hamengku Buwono (HB) III and af ter the corona-tion of the Sult an. A royal complex was built on the east

side of the River Code, which merged with the colonial set tlement on the southern shore of the river.

From the beginning of the 19th century, the Euro-peans became increasingly inÁ uential in government and economic issues. In 1822, the Societeit der Vereenig-ing (Communit y Leisure Centre) was est ablished in the residence of the Dutch Resident . Af ter the end of the Diponegoro War (1825-1830), the palaces of Yogyakart a and Pakualaman had a mainly decorative function, while political and bureaucratic power were in fact held by the Dutch Resident . Although their formal st atus was that of an independent st ate, the principles of st ate regula-tion of both Yogyakart a and Surakart a were under the control of the Dutch authorities. During this period, the number of colonial buildings, facilities and the popu-lation of Europeans increased. Artha (2000) describes a large area called Loji Kebon on the west side of the Vredeburg fort , which comprised a church, a school, a courthouse, and the Societeit der Vereeniging. The So-cieteit der Vereeniging was used for recreation by the European societ y in Yogyakart a, especially the Dutch. It featured facilities such as a ballroom, a music room, and areas for bowling, roulet te, horseracing and bet ting.

In 1887, Yogyakart a had t wo railway st ations, found-ed by t wo dif ferent companies. Lempuyangan st ation served the major line from Yogyakart a to Semarang (constructed by the NIS M ij S/ V in 1872) and Tugu Rail-way St ation served the major cities to the south and the west of Yogyakart a (constructed by the SS Spoor in 1887). The est ablishment of these st ations generated the development of public facilities in the surrounding area in the form of commercial facilities, rest aurant s and lodgings, such as the Hotel Tugu, which was founded in 1911 (Adishakti 1997). Other monument al buildings that were constructed during this period were the Java Bank (1914) on the north side of the Alun- alun Lor, and the M at aram Bank. The Dutch also built sport s facilities such as a racetrack that was constructed on the main route from Yogyakart a to Surakart a around 1903. (Fig. 8)

In 1909, primary and secondary schools, hospit al fa-cilities and sport s fafa-cilities were est ablished, as a part of a new Dutch set tlement known as Kotabaru (New Cit y).

Kotabaru covered an area of 100 hect ares and was re-stricted to European set tlers. In addition to it s promi-nent physical appearance that distinguished it from the surrounding villages, it s founding also included the displacement of indigenous villages (Darmosugito 1956 in Wibisono 2001) This process shows that in terms of land ownership, the interest s of the indigenous villages were of only minor interest to the Europeans at the time (Houben 1994 in Setiawan 2005).

The Period of the Republic

The role of the palace cannot be separated from the history of the Indonesian revolution and the power struggle against the colonial rulers. By 1945 the palace had become the secret headquarters for the Indonesian freedom À ghters. During this period, the palace became a place to which people were evacuated and sheltered from the at t acks of the Dutch.

In the early days of independence, the functions of some element s in the cit y were redeÀ ned. When Yog-yakart a became the capit al of Indonesia from 1946 to 1949, the former residence of the Dutch Resident was turned into the Great House, the residence of the presi-dent of the Republic of Indonesia. Political and econom-ic conditions at the time did not allow the muneconom-icipal- municipal-it y to inmunicipal-itiate big changes or development plans. Even though the cit y went from covering an area of 1480 acres in 1942 to covering 3250 acres only À ve years later, no infrastructure changes were implemented. Although the cit y experienced a deterioration of qualit y during this time, this period also marked the beginning of the formation of Yogyakart a as the national cit y of educa-tion.1 Institutions of higher education were est ablished, such as the Islamic Universit y of Indonesia (UII) in 1947 and the Gadjah M ada Universit y (UGM ) in 1949, and the number of institutions of higher education grew signiÀ -cantly2 (Fig. 9).

With the New Order government under Suharto in 1966, a new ideology of development af fected the lives of the people and the development of the cit y. One im-port ant aspect of this ideology was the idea to beautif y the cit y through improvement s to roads and the mod-ernization of the physical appearance of urban space. With funding from the central government , the cit y ofÀ -cials launched several cit y rejuvenation project s. The À rst project concerned the renovation of the district around

the M alioboro Street in the late 1970s and it can be said to have been successful. Nowadays the M alioboro Cor-ridor is known as a tourist destination and as one of the areas in Yogyakart a with intense public activit y (Fig. 10).

Contemporary Issues

The current spatial arrangement of Yogyakart a is based on the evolution of the structure of the cit y since it s est ablishment . The cit y has experienced many periods of formation with a variet y of factors that have created it s current form. The process of the evolution of Yogya-kart a is of course continuing. Some of the contemporary

Fig. 8: Beringharjo M arket af ter it s renovation in 1925. (Source: Sonobudoyo M useum Collection)

issues and phenomena that seem to affect the spatial arrangement of Yogyakart a will be discussed below.

Transportation

In his article “The Disappearing Cit y” Frank Lloyd Wright (1932) discussed the decentralization of the cit y through the presence of motor vehicles. We can see evidence of this theory in today’s cities, including Yog-yakart a, where the number of vehicles has steadily been increasing and additional housing development s out-side the cit y have resulted in an increasing movement bet ween different part s of the cit y. The urban transport net work has become increasingly crowded and it has be-come necessary to separate the transport system within the cit y from long-range transport . At the end of the 1990s a ring road project was completed in Yogyakart a, which aimed to reduce trafÀ c densit y within the cit y.

The ring road that was constructed some 2-5 kilo-metres out side of the administrative boundary of Yog-yakart a Cit y actually turned out to trigger the decen-tralization of the town centre. The centres of activities, such as campuses, residential areas, shopping malls and entert ainment centres can today be found in a radius of about 10 kilometres from the traditional downtown area. The larger dist ances bet ween the centres of activ-it y no longer allow for tradactiv-itional transport ation modes such as horse- drawn carriages or bicycles. Instead, mo-torcycles and cars are used in the urban spaces.

The problem of transport ation is a common issue in the public space of modern cities. Urban spaces are ex-ploited for the sake of circulation and the parking of ve-hicles, which is a manifest ation of personal space. In re-sponse to this problem, the awareness of cit y authorities and communit y alike has increased in the past decade to encourage public transport modes such as cit y buses and more environment ally-friendly transport ation such as bicycles.

Shopping Malls

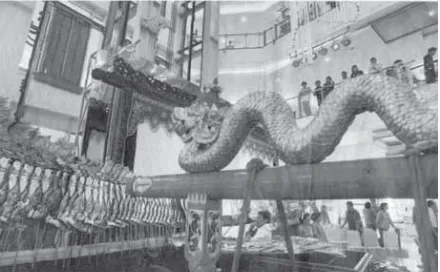

Kostof (1992) recorded the t ypology of the mall as a modern form of urban public space. Unlike the tradi-tional urban public spaces like the cit y square, the mall has a roof and is air- conditioned, which means that ac-tivities can be t aking place all day long, all year round. The est ablishment of malls in Yogyakart a began with the est ablishment of the M alioboro M all and the Galeria M all in the 1990s, followed by Plaza Ambarrukmo and Saphir Square in 2005. The malls feature recreational fa-cilities and shows that at tract the public are organized on a regular basis. The existence of malls has changed the public idea of recreational activities and the clean and comfort able malls are now preferred to former pub-lic recreation centres such as the Gembira Loka (zoo), the Sekaten Night M arket or the Yogyakart a Art Festival.

Markets

The market is an urban public space that has always existed in the cities. It is a space of economic interac-tion in the cit y. Economic globalizainterac-tion has produced international concept s of market s. In Indonesia today, traditional market s compete with large hypermarket s such as Carrefour or M akro. The product s sold in these hypermarket s are commodities from the global market-place, while local and regional product s are sold in tra-ditional market s. However, the global concept has also inÁ uenced market s on a medium- and small-scale level. Supermarket s such as Superindo, Alfa, Hero or Giant can be found in shopping centres and new district s, while the mini- market s, such as Indomaret , Alfamart or Circle K, t arget the residential areas.

The municipal authorities consider this situation to be unbalanced and unproÀ t able with regards to local product s. As a consequence, many traditional market s are being revit alized, including the Kuncen Klithikan M arket , a second- hand market , or the Dongkelan M ar-ket , where animals and plant s are sold. The measures undert aken were considered sufÀ cient to successfully defend the existence of traditional market s and even enhance their appeal, but in the long term a synergy

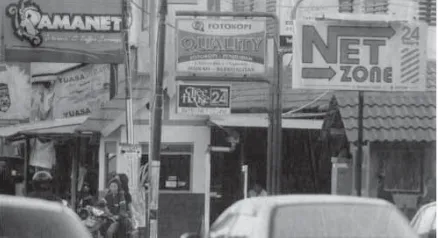

bet ween global and local forces needs to be considered or a unique and irreplaceable identit y needs to be built up. One example of a successful synergy is the tradi-tional Chinatown shopping area in the M alioboro cor-ridor, where street vendors sell local product s in front of shops of fering more global commodities (Fig. 11).

Settlement

Since they were À rst est ablished, the residential dis-trict s of Yogyakart a have consisted of village-like set tle-ment s known as kampung. In the early st ages of for-mation, the village concept was an integral part of the palace and the town and each kampung was associated with a speciÀ c communit y group. With the development of the cit y, where the palace no longer has full author-it y over the cauthor-it y and author-it s inhabauthor-it ant s, the concept of the

kampung has changed. During the 1970s, many new

kampung were formed in Yogyakart a, as the cit y grew. Setiawan (2005) categorized the existing villages in the urban area of Yogyakart a as follows:

1. Traditional kampung: The kampung was founded in an early period of formation of the cit y and is an area for a speciÀ c communit y. These kampung

are located close to the palace and their names point to the general character of the village. 2. Riverside kampung: These kampung are located

on the banks of three rivers that cross the cit y. M any villages of this category face formal issues, such as illegal occupancy.

3. Urban Fringe kampung: These rural set tlement s were transformed into set tlement s with a more urban character.

4. Illegal kampung: These set tlement s were illegally built on vacant land, such as Chinese cemeteries or river- and railway banks.

The categorization above gives an idea of the diver-sit y of the kampung in the cit y of Yogyakart a. In the early 20th century, modern t ypologies of set tlement s were est ablished by the Dutch in the region of what is now the

Kotabaru district , but these set tlement s were reserved for Europeans. During the 1970s modern housing ap-peared as a new t ypology of set tlement s in Yogyakart a. Government programs for public housing encouraged developers to meet modern st andards for large-scale housing.3 These new residential areas featured planned road structures, sanit ation and public facilities.4 The new set tlement s that were constructed from the 1970s to the 1990s conveyed new values that distinguished them from the kampung set tlement s. As a consequence, the terms orang kampung (village people) and orang perumahan (housing est ate people) appeared. Despite

Fig. 11: Leat her puppet show at t he mall, which serves as a new form of public space. (Source: Kompas, 16 August 2008)

the dif ferent values, during this period, planners made ef fort s to merge the new residential areas with the ex-isting structures, creating open housing est ate pat terns with high accessibilit y from all directions5(Fig. 12).

In the 1990s, with the proliferation of private inves-tors in the Yogyakart a real est ate sector, this concept st arted to change6. A high level of privacy and securit y was the priorit y of the new concept , with exclusivit y be-ing an additional sellbe-ing point . This concept has been adopted by virtually all sectors of real est ate developers in Yogyakart a today and is combined with the principles of the original housing areas, such as the regularit y of lot s, street pat terns, sanit ation and the availabilit y of public facilities. However, the previous access roads that were open in all directions have today been replaced by cul- de-sac layout , single- gate entrances and fences, which limit both visual and physical access. The direct impact of this new spatial pat tern is the formation of communit y residences based on re-segregation, which might be considered to be remotely similar to the prin-ciple of the kampung in the early st ages of the formation of the cit y of Yogyakart a (Fig. 13).

The transformation of set tlement s from the initial

kampung t ypology to the national housing system and modern housing est ates did not have a large impact on the formation and the character of public space. How-ever, nowadays, access to public spaces within modern set tlement s, such as roads, court yards or gardens, is limited, and restrictions are of ten enforced by private securit y companies. The Kot abaru housing facilities that were originally reserved for Europeans are an exception to this development . All facilities, including hospit als, parks, educational and sport s facilities are now public facilities and the gardens in the area and the Kot abaru Kridosono sport s complex in particular are popular pub-lic spaces in the cit y of Yogyakart a.

Tourism

The development of public functions cannot be sep-arated from the inÁ uence of the tourism sector. Aware of it s potential, the slogan ‘Yogyakart a - Never Ending Asia’ was developed to promote the cit y to international visitors. Although still limited to some extent , Yogya-kart a’s Adisucipto Airport caters to international Á ight s from Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. The promotion of the tourism sector has inÁ uenced the growth of lodging fa-cilities and trade, and today hotels and rest aurant s make up the second biggest economic sector in Indonesia behind the agricultural sector (DIY BPS- dat a 2007). The tourism sector has also provided employment for the informal sector, such as souvenir vendors, food, trans-port ation and tour guide services. The M alioboro Street – with it s batik and souvenir traders and food st alls – is a good example of how the informal tourist sector inÁ u-ences the spatial arrangement of the cit y.

Campus

The education sector also is a major driver of the cit y's economy. The higher education sector, in particular, pro-motes economic growth and spatial change and at tract s new resident s. In Yogyakart a, the universities are located on the edge of the cit y. In 2004, Bank Indonesia recorded that the average student spent around Rp1.000.000 per month, excluding tuition fees. Thus, the tot al amount of money spent by student s in Yogyakart a is estimated to amount to 2.8 trillion per year.7 Furthermore, most of the expenditure was invested in the service sector provided by the local communities, including lodgings, food st alls, photocopy and internet cafes (Fig. 14).

Figure 14 shows how a college campus can be a dominant generator of economic growth and of spatial changes in the cit y. Additionally, in the context of cur-rent global economic trends that impact consumption pat terns and result in rapid change, student s are mem-bers of the communit y that are rapidly absorbing those changes. One example of this can be observed in the Seturan area around the complex campuses of the UAJY, STIE YKPN, UPN Veteran and UII universities, where the past 10 years have changed the face of the region to ad-just it to the demands of student consumption pat terns. The original facilities such as lodging houses, food st alls and cof fee shops have been enhanced by additional fa-cilities such as laundry services, shops for printing digit al photos, internet cafes, vehicle- washing services and ga-rages, second- hand mobile- phone and netbook stores, cafes with Wi- Fi net works, and a sport s st adium. A new t ypology of urban public space is emerging around the campus (Fig. 15).

Public Open Space

Nowadays the open spaces most actively used for public activities in Yogyakart a are:

1. Alun- alun Lor

2. Kilometer Zero Area 3. UGM Campus Area 4. Taman Pintar (Smart Park) 5. Corridor M alioboro

Af ter m ore t han t wo cent uries, t he Alun- alun Lor

st ill feat ures m ost of it s original elem ent s such as t he palace, m osques, and banyan t rees, alt hough som e

el-em ent s, such as t he Pekapalan pavilion, have changed. Som e rit uals, like t he Sekaten- or t he Grebeg- Rit ual are st ill maint ained, mainly for the tourist s, while oth-er rit uals, such as t he Pepe-, t he Ram pogan- and t he

Watangan- Rit ual, are considered not to be in line wit h t he spirit of t he present era and t hus are no longer perform ed. The sout hern part of t he square, where t he kingdom’s soldiers once t rained, has now been m ade into a popular tourist at traction called m asangin (en-t rance be(en-t ween (en-t wo banyan (en-t rees). The square’s sacred at m osphere of the past has been greatly reduced but today the square ser ves as a true public space. Ever yone can m ove around freely, wit hout t he need of an aware-ness of t he cont ext of t he past , when t he square ser ved as a symbol of unit y. The use of t he Alun- alun Lor as a parking area also conÀ rm s t he absence of m em ories of t he sanct it y of t he square in t he past . Nevert heless, in a polit ical context , t he Alun- alun Lor st ill occupies t he m ost import ant posit ion as a public space and has been chosen repeatedly for declaring a st ance in a rit-ual known as Pisowanan Ageng. The Pisowanan Ageng

rit uals t ake place in t he nort hern part of t he square and involve tens of t housands of cit izens and t he king. Thus in 1998 people gat hered in t he Alun- alun Lor to sup-port t he reform of t he republic. In 2008, people gat h-ered in t he square to hear Sult an Ham engku Buwono X declare his intent ion to st and for t he 2008 president ial elect ion. The lat est gat hering in t he Alun- alun Lor was a cit izens’ protest to t he Kraton in 2010, for t heir right to conduct t he Pisowanan Ageng ritual and to keep t he privileged st at us of Yogyakart a (Fig. 16).

The area that is today known as the Kilom eter Zero Area used to be a region wit h European character. It is surrounded by t he Great House, t he Sonobudoyo M useum , the Vredeburg fort , Bank Indonesia, the Post OfÀ ce, Nat ional Bank Indonesia and t he Indonesian Protest ant Church of t he West and is st ill characterized as a public space wit h European- inÁ uenced art ifact s. The area feat ures a neater st ruct ure than the town square and t he act ivit ies t hat t ake place in t his area are m ore diverse and m ore dynamic, and of ten occur spont aneously. Event s and rit uals t hat t ake place in t his area reÁ ect cult ural and social aspect s of t he cit y. Thus, celebrat ions took place in t his area during t he Chinese New Year several years ago and groups have collected donations for the vict im s of the disaster of the eruption of M erapi (Fig. 17).

The Tam an Pintar (Smart Park) is an init iat ive by t he governm ent of t he cit y of Yogyakart a to provide a public space that combines the concept of urban en-t eren-t ainmenen-t wien-t h educaen-t ion. The area was developed

Fig. 14: Increasing number of education facilities in t he Yogyakar-t a area. (Source: AdishakYogyakar-ti 1997)

Fig. 16: From top down: t he area around t he Alun- alun Lor: a) Protesting citizens demanding their right to con duct t he

Piso-wanan Ageng Ritual; b) Grebeg Maulud Ritual in 2011; c) The

Se-katen Ritual (market and entert ainment) in t he N ort h Alun- alun; d) Game lan is played in t he court yard of t he Great M osque to at-t racat-t visiat-tors.

(Source: survey, 2010-2011)

Fig. 17: From top down: The Kilometer Zero Area: a) Unique piggy banks to raise money for victims of the M erapi disaster; b) Becak-fenders as decorative elements in the cit y, representing the existence of traditional transportation in the modern era; c) Lion dance during the carnival, representing the cit y‘s cultural pluralism; d) Grebeg

Maulud Ritual towards the Kepatihan, the administrative centre of

t wo decades ago and cont ains a cinema and a shop-ping- and entert ainm ent cent re, which can be accessed by t he cit y’s cit izens at low cost (Fig. 18).

The campus of the Gadjah M ada Universit y (UGM ) has been used by the people of Yogyakart a Cit y for pub-lic activities for a long time. The campus area is criss-crossed by public circulation routes which connect the campus with the cit y. In the 1980s and the 1990s, the Pancasila Square and the Campus Boulevard area were well known as open spaces where the cit y’s citizens would go to exercise, as well as for their street vendors. In the past decade, the character of the space, which was originally open to the public, has changed to a more private area. Authorities require stricter campus order for securit y and ease of maintenance of the campus en-vironment . Limiting the space accessible to the public generally discourages people from organizing activities around the campus area. The road in the east and west periphery of the campus and the boundary area are the only remaining public areas. Public activities occur mainly on the eastern side of the campus, including the Sunday M orning M arket , known as Sunmor. One activ-it y that has not changed over the past few decades is the student demonstrations, which always t ake place at t wo main point s: the Bundaran UGM (UGM roundabout) and in front of the Kantor Pusat (head ofÀ ce/ rectorate)

(Fig. 19).

Conclusion

The morphology of the public space of Yogyakart a cit y is full of history and inÁ uences from the cit y’s forma-tion. A transformation process is always occurring and changes concern the physical form as well as the con-cept of public space it self. Some of the physical artifact s and rituals in the cit y’s public spaces have survived to this day and have found new meaning in the context of the present era. It can be said that the public space in the cit y of Yogyakart a is still trying to preserve the core values that shaped it s identit y.

The public’s at titude towards situations such as the struggle to reform the republic, the conÁ ict with the central government policy, the desire to assert the cit y's cultural pluralism, the earthquakes and the eruption of M ount M erapi are clearly reÁ ected in the cit y’s public spaces. Rituals, carnivals, demonstrations and exhibi-tions are only some of the activities that t ake place in the public spaces of the cit y of Yogyakart a to express the public’s at titudes towards actual conditions. In this context , the public spaces selected remain the public spaces of the traditional cit y: the main cit y square, the

Kilometer Zero or the Corridor M alioboro. In expressing their collective at titudes, the citizens of Yogyakart a are always looking for spaces that clearly reÁ ect the cit y's identit y. The palace, the main square, and the M alioboro Road are places with a strong character that provide a st age for the event s.

On the other hand, economic globalization and in-formation are factors which drive the in-formation of new t ypologies of public space in the cit y. One of the ma-jor agent s for change of the cit y is the college campus, with dynamic young immigrant s who have a thirst for new things. Therefore, new t ypologies of public space are springing up around the campus area. One of the most active modern urban public spaces is even located out side the administrative boundaries of the cit y, close to the college area at the eastern end of town. Never-theless, this new t ypology of public space has not had a strong inÁ uence on the formation of urban identit y. The market in these areas is dominated by national or even global brands and is in line with the wishes of consumers who want to connect themselves with the world.

A new form of public space that is clearly trying to associate it self with the identit y of Yogyakart a is occu-pied by tourist facilities such as hotels and rest aurant s, whose aim is to of fer a distinctive ‘Yogyakart a feeling’ as strongly as possible. The venues are not limited to upper class economic facilities, such as cafes or hotel rest au-rant s. Even at the lowest economic level, the angkringan

(street vendors) are an integral part of the unique atmo-sphere of Yogyakart a.

Despite these new public spaces, there needs to be a discussion as to whether the public character of the cit y should be oriented solely on economics. The economic character of public space result s in cert ain limit ations for the owners, since people are not free to express them-selves, for example in terms of ideology, political at ti-tudes, or ritual. Similarly, the ‘allocation’ of cert ain public spaces to cert ain economic classes has led to restricted access of the communit y as a whole.

This issue has been t aken on board by t he pres-ent Cit y Governm pres-ent , which is focusing on a balanced developm ent of urban public spaces that are relatively accessible to all levels of societ y. The governm ent is continuing to maint ain the traditional public spaces such as t he town square, t he Kilom eter Zero, t he Corri-dor M alioboro and t he Beringharjo market . In addit ion, new public spaces have been created with the devel-opm ent of educat ional areas such as t he Tam an Pin-tar, t he t ransformat ion of t he old t erminal into a park, t he revit alizat ion of t he market and t he revit alizat ion of t he open space by t he riverside. The cit y govern-ment ’s design approach usually follows t he paradigm of positivism and determinism and is of ten top- down. This approach is underst andable, considering the con-st raint s of an unprepared bureaucrat ic sycon-stem which À nds it hard to deal wit h public part icipat ion m et hods t hat tend to t ake a long t im e. Som e of t he concept s for new public spaces t hat tend to minimize govern-m ent involvegovern-m ent will in fut ure be incorporated into the dist inct ive identit y of Yogyakart a. The pursuit of as-pect s of design novelt ies tends to be emphasized and ident it y is limited to decorat ive elem ent s and st reet furnit ure.

The reformation of the design approach and of the management of public spaces would need to be a step-by-step process and needs to be a communal process involving, among others, all st akeholders, the palace, the government , the private sector, consult ant s, academics and the citizens of the cit y. In order to achieve a positive synergy and mutual beneÀ t s, the whole communit y has to be involved in the planning and the designing of the cit y’s public spaces.

Then, the emerging character of the cit y will pos-sess a strong identit y, which will be expressed in public spaces. Identit y is an import ant factor in preparing cities (and citizens) for continuing the transformation of the soul of the cit y at several levels in the demanding era of globalization. The identit y needs to be raised from an awareness of historical and cultural context , not only by planners, but also by users. It is import ant to underst and that user-awareness of urban public space will link the historical and the cultural context s, which are the deter-mining factors. Thus, planning approaches using partici-patory methods that include all potential users need to be considered in the future.

References

1 This process was st arted during the Japanese occupation,

when all Dutch schools were converted into Indonesian schools. During the years of revolution and the struggle for independence (1945-1950), there was a rapid increase of educational facilities as the government and private en-tities est ablished private schools and public high schools (Khudori 2002).

2 In 2007, a tot al of 235,616 st udent s were st udying in 127

institutions for higher education (universities, institutes, high schools, colleges, and polytechnics) in the Province D.I. Yogyakart a

3 Setiawan (2005) recorded that 14000 housing unit s were

constructed in 73 locations by the Perusahaan Umum

Pembangunan Perumahan N asional (National Housing Agency) and by 32 private developers from 1973 to 1995.

4 This concept had been around since the construction of

the Dutch set tlement s in Bint aran and Kot abaru in the

early 19t h cent ury, but it had been limited to the European

set tlers.

5 Examples of the housing project s of the 1970s that

fol-low this concept include New Pogung, Housing Bull and Perumnas Condongcatur.

6 The concept of fenced- of f housing est ates with

single-gate access has become a new trend in Indonesia, includ-ing Yogyakart a, since the 1990s. Some examples of hous-ing est ates that follow this concept are M at aram Bumi Se-jahtera, Castle Gejayan, Kaliurang Prat t and Taman Griya Indah. The t arget demographics for these housing est ates are the economic middle- and upper classes.

7 According to research carried out by the YUDP

(Yogya-kart a Urban Development Project) in 2001, approximately 70% of st udent s are immigrant s from out side the region of Yogyakart a.

Bibliography

Adishakti, L.T., 1997: A Study on the Conservation Planning of

Yogyakarta Historic- tourist Cit y Based on Urban Space Her-itage Conception, dissert ation, Graduate School of Global Environment al Engineering, Kyoto Universit y, Japan.

Artha, A.T., 2000: Yogyakarta Tem po Doeloe, Sepanjang Cat at an

Pariwisat a.

Carr, S. & Francis, M ark & Rivlin, Leanne G. & Stone, Andrew

M ., 1992: Public Space, Cambridge (Cambridge Universit y

Press).

Danisworo, M ., 2004: Pem berdayaan Ruang Publik Sebagai

Tem pat Warga Kota Mengekspresikan Diri, Kawasan Gelora Bung Karno. Paper in Seminar & Workshop: Pemberday-aan Area Publik di Dalam Kot a. Jakart a- Ikat an Arsitek In-donesia (IAI).

Gavent a, S., 2006: N ew Public Space. London (M itchell

Beazley-Octopus Publishing Group).

ht tp:// www.mangunwijaya.or.id (downloaded 7t h of January

2001).

Ikaputra, 1995: A Study on the Contem porary Utili zation of the

Javanese Urban Heritage and its Effect on Historicit y: An At tem pt to Introduce the Contextual Adaptabilit y into the Preservation of Historic Environm ent of Yogyakarta, disser-t adisser-tion, Graduadisser-te School of Engineering, Osaka Universidisser-t y, Japan.

Ikaputra, 2004: Towards Open and Accessible Public Places,

Con-Á ict and Com promise, in: Proceedings M anaging ConÁ ict s

in Public Spaces Through Urban Design, 1st International

Seminar National Symposium , Exhibition and Workshop in Urban Design, Prayitno, B. & Poerwadi, Setiawan, A.T. & Aji, D.P. (eds.), M aster Program in Urban Design, Post-graduate Program , Gadjah M ada Universit y, Yogyakart a.

Khudori, D., 2002: Menuju Kam pung Pem erdekaan, Mem

ban-gun Masyarakat Sipil dari Akar- akarnya Belajar dari Rom o Mangun di Pinggir Kali Code. Yogyakart a (Yayasan Pondok Rakyat).

Kompas, 19 July 2008, Seturan Menuju Kawasan Hiburan,

Ja-kart a.

Kompas, 16 August 2008, Si Petruk Tujuh Belasan di Mal.,

Ja-kart a.

Kostof, S., 1992: The Cit y Assembled: The Elem ents of Urban

Form Through History, London (Thames and Hudson).

Lang, J., 2005: Urban Design, A Typology of Procedures and

Products, Oxford / Burlington (M A) (Architect ural Press).

Lombard, D., 1996: N usa Jawa Silang Budaya: Batas batas Pem

-baratan, Jakart a (Gramedia Pust aka Ut ama).

M adanipour, A., 1996: Design of Urban Space: An Inquiry into a

Socio- spatial Process, Chichester (John Wiley & Sons).

Purwanto, E., 2004: Rukun Kota (Ruang Perkotaan Berbasis

Bu-daya Guyub), Poros Tugu Pal Putih sam pai dengan Alun-Alun Utara Yogyakarta, unpublished doctoral thesis, Gad-jah M ada Universit y, Yogyakart a.

Rossi, A., 1982: The Architecture of the Cit y, Cambridge/ M

as-sachuset t s/ London (M IT Press).

Santoso, J., 2006: [M enyiasati] Kota Tanpa Warga, Kepust akaan

Populer Gramedia – Centropolis, Universit as Tarumana-gara, Jakart a.

Santoso, J., 2008: Arsitektur – Kota Jawa, Kosm os, Kultur &

Kua-sa, Centropolis, Universit as Tarumanagara, Jakart a.

Setiawan, B., 2005: "Yogyakart a Cit y in Transformation: The

Need for A Bet ter Planning Approach", Jurnal

Perenca-naan Kota dan Daerah, Volume 1, Nomor, Edisi 1, Gadjah M ada Universit y, Yogyakart a.

Wibisono, B.H., 2001: Transform ation of Jalan Malioboro,

Yo-gyakarta: The Morphology and Dynamics of a Javanese Street, dissert ation, Facult y of Architect ure, Building and Planning, The Universit y of M elbourne.

Widodo, J.W., 2004: The Boat and the Cit y, Chinese Diaspora

and the Architecture of South East Asian Coastal Cities, Sin-gapore (M arshall Cavendish Academic).

Wiryomartono, A.B.P., 1995: Seni Bangunan dan Seni Binakota

di Indonesia; Kajian m engenai konsep, struktur, dan elem en

À sik kota sejak perdadaban Hindu- Budha, Islam hingga sekarang, Jakart a (Gramedia Pust aka Ut ama).

Wright , Frank Lloyd, 1932: The Disappearing Cit y, New York

(William Farquhar Payson).

Zaidulfar, E.A., 2002: Morfologi Kota Padang, unpublished