Exposure to Fluoxetine

Lee S. Cohen, Vicki L. Heller, Jennie W. Bailey, Lynn Grush,

J. Stuart Ablon, and Suzanne M. Bouffard

Background: Although pregnancy has frequently been described as a time of emotional well-being, some women experience significant antenatal depression that may re-quire treatment with antidepressants. The purpose of this investigation was to examine the relative effects of early and late trimester exposure to fluoxetine and perinatal outcome.

Methods: Obstetric and neonatal records were reviewed for 64 mother–infant pairs where there was documented use of fluoxetine at some point during pregnancy. Differ-ences in several measures of obstetrical outcome and neonatal well-being were examined in early trimester– and late trimester– exposed infants.

Results: No differences in birth weight and acute neonatal outcome were evident across the two groups, though there was a higher frequency of special care nursery admissions for infants with exposure to fluoxetine late in pregnancy. Special care nursery admissions could not be attributed to any specific factor.

Conclusions: Given the growing numbers of women who are treated with antidepressants, including fluoxetine, during pregnancy, and the strong association between depression during pregnancy and risk for postpartum depression, patients may be best advised to continue treatment with antidepressants through labor and delivery versus making any change in intensity of treatment during the acute peripartum period. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:

996 –1000 © 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry

Key Words: Pregnancy, depression, fluoxetine, perinatal

outcome

Introduction

S

everal studies describe a prevalence of major depres-sion during pregnancy of 5–10% (O’Hara 1986; O’Hara et al 1991). Investigators have also noted that pregnant women with histories of recurrent major depres-sion are at high risk for relapse after antidepressant discontinuation at or around the time of conception (Co-hen 1999). In addition, the finding of high risk for major depression in women during the childbearing years (Kessler et al 1993) increases the likelihood of potential need for antidepressants during pregnancy. This raises obvious concerns regarding the reproductive safety of antidepressants. Multiple reports describe the absence of higher rates of major congenital malformations in infants with and without histories of prenatal exposure to fluox-etine (Chambers et al 1996; Pastuszak et al 1993). A low incidence of perinatal toxicity in newborns whose mothers are treated with these medications during labor and deliv-ery has also been reported (Goldstein 1995); however, one study (Chambers et al 1996) has described poor perinatal outcome following prenatal exposure to fluoxetine with associated higher rates of 1) prematurity, 2) low– birth weight babies, 3) admissions to special care nurseries (SCNs), and 4) “poor neonatal adaptation.” Findings were greatest for newborns exposed to fluoxetine late in preg-nancy, as compared with those exposed in the first and second trimesters. The purpose of our investigation was to examine obstetric and neonatal outcomes associated with early and late prenatal exposure to fluoxetine. In addition, reasons for admission and outcomes of admission to SCNs (if any) were evaluated in infants with prenatal exposure to fluoxetine.Methods and Materials

Obstetric and neonatal records of 64 newborns with histories of fluoxetine exposure during pregnancy were reviewed by two of us (LSC, VLH). These infants were born to women who suffered from mood and anxiety disorders, many of whom had been observed as they went through the Perinatal and Reproductive Psychiatry Program at Massachusetts General Hospital. Women typically had presented for consultation to the program either

From Perinatal and Reproductive Psychiatry Clinical Research Program, Depart-ment of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School (LSC, JWB, LG, JSA, SMB), Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School (VLH), Boston, and Franciscan Children’s Hospital, Brighton (LG), Massachusetts.

Address reprint requests to Lee S. Cohen, M.D., Massachusetts General Hospital, Perinatal and Reproductive Psychiatry Clinical Research Program, Department of Psychiatry WAC 815, 15 Parkman St., Boston MA 02114.

Received November 16, 1999; revised March 1, 2000; accepted March 3, 2000.

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

before or during pregnancy with requests for information regard-ing relative risks of prenatal exposure to psychotropics and untreated maternal psychiatric illness. Patients provided written consent to release obstetric and neonatal records.

Characteristics of interest in women who took fluoxetine during pregnancy were 1) dose and duration of fluoxetine exposure, 2) timing of exposure (early [trimester I and/or trimester II] vs. late [at least trimester III to delivery]), 3) age, 4) parity, 5) method of delivery (vaginal vs. cesarean), 6) duration of active labor, 7) use of other psychotropics during pregnancy, and 8) delivery at tertiary versus community hospitals. Outcome variables of interest included 1) 5-min appearance, pulse, gri-mace, activity, and respiration (APGAR) score; 2) birth weight; 3) gestational age at delivery; 4) presence of poor neonatal adaptation, defined as jitteriness, respiratory difficulties, hypo-glycemia, lethargy, and poor color or tone; 5) admission to SCN (level 2 or 3) for any length of time; and 6) timing of discharge from the hospital (with or without mother).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to test the null hypothesis that there would be no differences in outcome measures between early and late exposed infants. Differences in continuous out-come data were examined using two-tailed t tests, and differ-ences in categorical data were examined using x2 analysis and Fisher’s exact p values.

With respect to analysis of outcome variables of interest, preterm infants (n 5 3) were included for the purpose of examining the relationship between fluoxetine exposure and gestational age at delivery. Preterm infants were excluded, however, from analysis of birth weight differences between early trimester– and late trimester– exposed infants so as not to inappropriately skew the mean birth weights of both groups in question (early vs. late trimester exposure to fluoxetine).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Obstetric and neonatal records were reviewed for 64 mother–infant pairs where records allowed for accurate

assessment of the outcome variables of interest. Women treated with fluoxetine had a mean age of 34 (range 23– 42 years); approximately half (n 5 33) were primiparous. Mean dose of fluoxetine during pregnancy was 27 mg/day (range 10 – 60 mg/day). Seventeen percent (n 5 11) of subjects used antidepressants during trimesters I and/or II only and the balance (83%, n555) used the medication during at least the third trimester and through delivery. Twenty-five women (39%) were noted to have been treated concurrently with other psychotropics such as benzodiazepines during pregnancy.

Neonatal Outcome

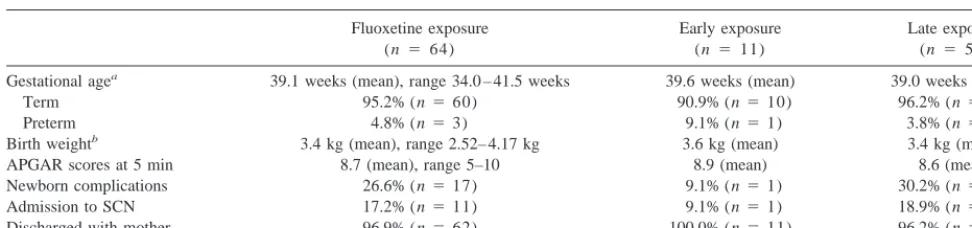

Neonatal outcome across the variables of interest (ges-tational age, birth weight, APGAR scores, presence of neonatal complications, and disposition of the newborn) is summarized in Table 1. No significant differences were noted between the early and late exposed infants with respect to gestational age at delivery, birth weight, APGAR scores, or timing of maternal–infant discharge; however, three- and twofold increases in frequency of newborn complications and SCN admissions were noted in those infants exposed to fluoxetine later in pregnancy and those with earlier exposure, respectively. The findings did not attain statistical significance (x2 5

2.08, p5.15;x250.61, p5.43, respectively) because power (.35 and .14, respectively) was constrained by the limited sample size, especially in the early exposure group (n5 11). There was also a trend towards longer duration of fluoxetine exposure among those infants who were admitted to the SCN, as compared with those infants who were not admitted [M 5 31.21 vs. 22.21 weeks of exposure, respectively; t(59)51.79, p5.08]. Again, this difference was not statistically significant because power (.45) was constrained by limited sample size in the small cell.

Table 1. Neonatal Outcome: Gestational Age, Newborn Complications, and Birth Weight in Infants of Women Treated with Fluoxetine

Gestational agea 39.1 weeks (mean), range 34.0 – 41.5 weeks 39.6 weeks (mean) 39.0 weeks (mean)

Term 95.2% (n560) 90.9% (n510) 96.2% (n540)

Preterm 4.8% (n53) 9.1% (n51) 3.8% (n52)

Birth weightb 3.4 kg (mean), range 2.52– 4.17 kg 3.6 kg (mean) 3.4 kg (mean)

APGAR scores at 5 min 8.7 (mean), range 5–10 8.9 (mean) 8.6 (mean)

Newborn complications 26.6% (n517) 9.1% (n51) 30.2% (n516)

Admission to SCN 17.2% (n511) 9.1% (n51) 18.9% (n510)

Discharged with mother 96.9% (n562) 100.0% (n511) 96.2% (n551)

APGAR, appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration; SCN, special care nursery. aTerm and preterm infants total 63, due to missing data on one infant.

SCN Admissions and Neonatal Complications

Specific nature of neonatal complications observed in infants exposed to fluoxetine and their relationship to SCN admission were examined for the 17 infants who experi-enced such difficulties during pregnancy (Table 2). A particularly broad and common spectrum of complications was seen in the infants. Admissions to the SCN tended to be brief and were primarily for the purposes of observa-tion, with all but two children noted as having been discharged from the hospital with their mothers.

Discussion

Our findings have significant clinical implications. With a growing literature indicating that women are not

“protect-ed” from depression during pregnancy (Cohen 1999; O’Hara et al 1991), concerns regarding the safety of prenatal exposure to antidepressants are particularly ap-propriate. Conversely, untreated depression during preg-nancy has also been associated with poor perinatal out-come (Orr and Miller 1995). Aside from the potential impact of antenatal depression on acute neonatal outcome, data suggest that depression during pregnancy and past history of depression are strong predictors of postpartum depression (O’Hara et al 1991). If concerns regarding fluoxetine use late in pregnancy prompt discontinuation of drugs at or around delivery (Wisner et al 1999), women would run the risk of increased maternal morbidity sec-ondary to relapse of depression as they proceed into a period of already increased risk for depression such as the Table 2. Neonatal Complications (n517) and Special Care Nursery (SCN) Admissions (n511)

in Infants Exposed to Fluoxetine during Pregnancy

Subject number Nature of complication

SCN admission

Discharged with mother

1a Admitted to SCN for 20 min, infant noted to

be pale

Yes Yes

2 Infant jittery, hypoglycemia with blood sugar

level538

No Yes

3 Infant noted to be lethargic, infection work-up

negative

Yes Yes

4a Premature at 34 weeks, prolonged premature

rupture of membranes, TTN, infection work-up negative

Yes Yes

5 Infant noted to be jittery, prolonged rupture of

membranes with fever

Yes Yes

6 Thick meconium, observed in SCN and

discharged

Yes Yes

7 TTN resolved Yes Yes

8 Thick meconium, treated with antibiotics,

negative blood culture, maternal flu with rhinitis and fever

Yes Yes

9 Admitted to SCN for “grunting,” infection

work-up negative

Yes Yes

10 Infant noted to be jittery for 1 hour No Yes

11a,b Observed in SCN because of concern for

clonazepam exposure

Yes Yes

12 Hyperbilirubinemia, hypoglycemia (mother

diabetic), resolved at first feed

No Yes

13a TTN, supplemental oxygen for 48 hours, easy

agitation initially, hyperbilirubinemia

Yes No (3 extra days)

14 Respiratory distress, desaturation episode after

choking on mucous31, treated with antibiotic for 48 hours, negative blood culture

No No (1 extra day)

15a OB: cesarean section for arrest of descent,

ruptured membranes; uterine atony, postpartum hemorrhage; PUPPS; TTN

No Yes

16 TTN Yes Yes

17 Left facial droop, hypospadias, left arm skin

lesion

No Yes

TTN, transient tachypnea; OB, obstetric; PUPPS, pruritic urticarial papules/pustula of pregnancy. aThese mothers were taking other psychotropic medications at the time of delivery.

puerperium. The focus of our investigation was thus to examine the question of relative impact of fluoxetine exposure during pregnancy as a function of timing of exposure (i.e., early vs. late). This study was not designed as a controlled study of incidence of congenital malfor-mation or perinatal complications in infants with and without prenatal exposure to fluoxetine.

In our series, late trimester exposure to fluoxetine was associated with a greater frequency of admission of infants to the SCN, as compared with those with early trimester exposure to the medication (18.9% vs. 9.1%). This differ-ence is similar to relative rates of SCN admission in late and early exposed infants described by Chambers (23% vs. 9.5%). Similarly, the rate of newborn complications in late and early exposed infants in our sample (30.2% vs. 9.1%) was similar to the relative rates of poor neonatal adapta-tion across these two groups as described by Chambers (31.5% vs. 8.9%); however, in our series admission to the SCN did not appear to be driven by any single variable.

The effect size of the difference in rates of SCN admission between early and late exposed infants was small; however, we also observed a medium-sized effect of infants who were admitted to the SCN being exposed to fluoxetine for longer periods of time than infants who were not admitted. Moreover, the clinical significance of SCN admission seemed limited; all but two infants failed to be discharged with their mothers within the extremely short duration of the perinatal hospital stay. The extent to which poor neonatal adaptation with such nonspecific symptoms as tachypnea, jitteriness, hypoglycemia, and poor tone or color can be specifically attributed to fluox-etine exposure versus other associated maternal conditions (e.g., fever, prolonged premature rupture of membranes, presence of thick meconium, coadministration of other psychotropics noted in our sample of patients), including depression, needs to be reconsidered.

There were several obvious limitations in the study. First, it was retrospective in nature, with relatively small numbers of cases. The small sample size, especially in the early exposure group, greatly limited our power to detect statistically significant differences in outcome measures between early and late exposed infants. For example, given the medium effect size of the difference we ob-served in frequency of newborn complications (30.2% vs. 9.1%), 55 subjects would be needed in each group to obtain .80 power to detect statistically significant differ-ences (assuminga 5.05). With respect to the small effect size of the difference we observed in frequency of SCN admissions (18.9% vs. 9.1%), 188 subjects would be needed in each group to obtain .80 power to detect statistically significant differences (assuming a 5 .05). The second limitation in the study was the absence of two relevant control groups. Ideally, these would have

in-cluded pregnant women with neither history of mood and anxiety disorders nor history of drug exposure as well as a group of those without medication exposure but with a history of one or more major depressive episodes. Such control groups would have allowed for a more rigorous delineation of the potential effects of fluoxetine on neo-natal outcome. For example, it is particularly difficult to separate the effect of the two relevant exposures (depres-sion and fluoxetine use during pregnancy) when examin-ing the findexamin-ings of longer duration of medication exposure in infants admitted to the SCN. Given the probable association between severity of depression and duration of fluoxetine use during pregnancy, the delineation of rela-tive contribution of each of these variables to the outcome, admission to SCN, becomes problematic. Women taking fluoxetine during the third trimester may have required this treatment due to relapse during pregnancy, which either did not occur as frequently in the early group or did not occur as severely in the early group. Another possi-bility is that those women taking fluoxetine during the third trimester had more severe prior episodes of depres-sion than the early group, associated with prior pregnan-cies and the puerperium or not, and were treated with fluoxetine prophylactically during the current pregnancy. In both of these scenarios, severe depression would emerge as a confound in the analysis of the outcome variables (complications and SCN admissions). Unfortu-nately, the retrospective nature of our data did not allow us to investigate the role of depressive relapse in medication status during pregnancy and delivery.

A great variety of factors may contribute to obstetric and neonatal outcome as well as acute disposition of the newborn (i.e., the SCN). These may include 1) pregravid maternal medical and psychiatric illness, 2) obstetric factors, 3) prenatal exposure to psychotropic and nonpsy-chotropic drugs, and 4) biases of clinicians and institutions with which they are affiliated. No clinical decision is risk free. Patients and their doctors must collaborate to make thoughtful decisions regarding use of psychiatric medica-tions before, during, and after pregnancy, as relative risks are weighed with the best data available as treatments are matched to individual clinical situations.

This research was supported in part by a grant from Eli Lilly and Co.

References

Chambers C, Johnson K, Dick L, Felix R, Jones KL (1996): Birth outcomes in pregnant women taking fluoxetine. N Engl J Med 335:1010 –1015.

Goldstein DJ (1995): Effects of third trimester fluoxetine exposure on the newborn. Clin Psychopharmacol 15:417– 420.

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz M, Blazer DG, Nelson CB (1993): Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. J

Affect Disord 29:85–96.

O’Hara MW (1986): Social support, life events, and depression during pregnancy and the pueperium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:569 –573.

O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW (1991): Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders:

Psychological, environmental, and hormonal factors. J

Ab-norm Psychol 100:63–73.

Orr S, Miller C (1995): Maternal depressive symptoms and the risk of poor pregnancy outcome. Review of the literature and preliminary findings. Epidemiol Rev 17:165–171.

Pastuszak A, Schick-Boschetto B, Zuber C, Feldkamp M, Pinelli M, Sihn S, et al (1993): Pregnancy outcome following first-trimester exposure to fluoxetine (Prozac). JAMA 269: 2246 –2248.

Wisner K, Gelenberg A, Leonard H, Zarin D, Frank E (1999): Pharmacologic treatment of depression during pregnancy.