122226 SE Linguistics Seminar: Usage-based grammar / BA Paper

WS 2013/14

No negation is not ambiguous:

negative raising

Lecturer: Priv. Doz. Dr. Mag. Gunther Kaltenböck, MA BA Paper English and American Studies A 033 612

Nico Sommerbauer

Matrikelnummer: 0908059

Table of Contents

List of figures ………...i

List of tables……….i

1. Introduction ... 1

2. What is neg-raising? ... 2

2.1 Defining negation ... 2

2.2 Defining neg-raising: ... 5

2.3 Approaches to neg-raising ... 8

2.3.1 The syntactic approach ... 8

2.3.2 The semantic/pragmatic approach ... 10

2.3.3 The ‘general ambiguity of negation’ approach ... 12

3 Corpus research ... 13

3.1 Methodology ... 13

3.2 Corpus study and results ... 14

3.2.1 COCA and BNC: geographical data ... 14

3.2.2 COHA: historical data from 1810-2009 ... 17

3.2.3 The GloWbE: an international web-based comparison ... 19

3.2.4 ICE-GB: further data on contemporary British English ... 22

3.2.5 Conclusion ... 23

4 Possible reasons for neg-raising ... 24

5 Conclusion ... 28

List of figures

Figure 1 Frequency of I don’t think in American English between 1810 and 2009 19 Figure 2 Frequency of I do not think in American English between 1810 and 2009 19 Figure 3 Frequency of not supposed to in American English between 1810 and 2009 20 Figure 4 Frequency of I don’t think in the GloWbE 21 Figure 5 Frequency of not supposed to in the GloWbE 22

List of tables

1.

Introduction

The present paper deals with the issue of negation raising, from here on referred to as neg-raising. The research question for this paper is what is negation raising, how and

how often do speakers use it, and what is its purpose?

Section 2 will offer the theoretical background for this paper; in subsection 2.1, we will establish a short definition of negation in order to be able to then define neg-raising in subsection 2.2. Then, we will look at some of the most widespread approaches to neg-raising in subsection 2.3, starting with the syntactic approach – the oldest approach to neg-raising – before moving on to approaches within the semantic and pragmatic paradigm of linguistics, and finally discussing the idea that neg-raising as its own independent phenomenon does not exist and is merely a manifestation of the general ambiguity of negation. Section 3 will focus on the corpus study conducted in producing this paper in an attempt to answer the question how and how often do speakers use [neg-raising]? Subsection 3.1 will give an overview of the methodology, outlining which

corpora were used and to what end before presenting the results and possible

interpretations in subsection 3.2. Section 4 of the present paper will then discuss why people may use neg-raising in an attempt to respond to the question what is its purpose? Due to its scope – and perhaps also due to the nature of neg-raising – this paper is not able to exhaustively answer all parts of its research question; it will, however, give some information on each part of the question. Further research

2.

What is neg-raising?

In this section, we will establish a definition for and different approaches towards negative raising –from here on referred to as ‘neg-raising’. In order to do this, we must first define the term negation so as to be able to define neg-raising, as the latter is intrinsically connected to the former.

2.1 Defining negation

In order to define neg-raising, we must first define negation. Before we can look deeper

into a possible definition, it has to be clarified that the term ‘negation’ is intrinsically

ambiguous in the sense that it can refer to the operation of negating (something), to the operator utilized to achieve this (a sign of negation, such as not) or the result of said operation. These three elements are of course closely connected to each other. As

such, I will use the term ‘negation’ to refer to the operation, like Napoli (2006: 234). Intuitively, one would probably say that negation is the reversal of an affirmative sentence, in order words there is a “functional asymmetry of affirmation and negation” (Horn 1989: 202). This is true in some cases, such as the examples in (1).

(1) a. The world is not flat. b. He is not at home.

c. I do not owe you anything.

However, as Giora (2006: 979) points out, there are many situations in which negation is used as a mitigation device rather than to reverse the affirmative sentence. Consider the examples in (2).

(2) a. Sebastian is not tall; he is about average in height.

In these examples, the antonyms to tall and far would be short and near, respectively. But the examples in (2) do not mean Sebastian is short or the restaurant is near. Here, the negation functions as a means of scaling rather than a reversal of the affirmative.

Additionally, negation can be used as a rhetoric device to express the notion that an adjective is not quite strong enough to express the intended meaning. Consider the examples in (3).

(3) a. The food wasn’t good. It was delicious!

b. His acting wasn’t just bad, it was downright awful!

In utterances such as the ones above, negation does not act as a reversal of affirmation. While the initial statement is negated, the second part of the utterance elaborates on the

speaker’s intentions, clarifying that the first part of the utterance is not rejected as

incorrect, but rather as too weak to express the speaker’s opinion. In a sense, this could

be labeled as a kind of ‘phrasal intensifier’, as the speaker utilizes an entire utterance to

replace a given adjective with a stronger adjective carrying the same base meaning.

Another ‘irregular’ use of negation – meaning it does not express the reversal of an affirmation – is scalar-implicature negation or denial. This means that a negated sentence including a term for some or a similar meaning implies that the subject of the negated sentence actually applies to all rather than some. For illustration, see (4).

(4) The sun is not larger than some planets: it is larger than all planets. (Horn 1989 quoted in Davis 2011: 2549).

Beukeboom, Finkenauer and Wigboldus (2010: 978) argue that a “negation bias” exists

which makes it more likely for people to refer to “stereotype-consistent behavior” using

affirmative sentences and to “stereotype-inconsistent behavior” by using negated sentences. This means, for example, that if Tracey is a woman, speakers would be likely to produce a sentence such as Tracey is short, but if Tracey is a man, they are more likely to produce a sentence such as Tracey is not very tall. This difference occurs because it is a general assumption – a stereotype – that men are taller than women. Their argument is mostly built around more social stereotypes, such as relating certain professions or social groups to different levels of intelligence or education, but I suggest that this negation bias can be observed just as much in examples relating to more physical factors such as above.

Beukeboom, Finkenauer and Wigboldus (2010: 980-988) also conducted several studies with students of VU University Amsterdam, all of which confirmed their argument that stereotype-inconsistent behavior is expected to be expressed via the use of negation whereas stereotype-consistent behavior is expected to be expressed via the use of affirmation. This is interesting to the topic of this paper because part of the research

question is ‘why do speakers use neg-raising?’, and pragmatic issues such as stereotyping and social biases are of relevance to this discussion.

I have stated at the beginning of this section that the term negation is ambiguous due to the fact it can refer to a negative operation, the operator used for it or the result of the operation. However, negation is also ambiguous in another sense: many negations can be interpreted in more than one way; indeed, it can even be argued that all negated utterances are semantically ambiguous. As Kjellmer (2000: 122) points out, a sentence

such as the title of his article “no work will spoil a child” can be interpreted in more than

the conclusion that both synthetic as well as analytic negated sentences are ambiguous. This underlying ambiguity of negation, which has been discussed in countless works over the years, including Ayer (1952), Horn (1989), Napoli (2006) and many more, is of critical importance to any discussion on raising, as the ambiguous nature of neg-raised utterances could, at least in some cases, arise from the ambiguity of negation itself rather than the process of neg-raising; in other words, the same sentence in its ‘un

-raised’ form may be just as ambiguous as the neg-raised version.

This is an argument also brought forth, for example, by Napoli (2006: 250-251). He argues that neg-raising may not be an actual phenomenon, but rather “another instance

of the ambiguity of negation”. We will discuss this point in more detail in subsection 2.3.3.

2.2 Defining neg-raising:

After establishing a definition of negation, we can now move on to defining neg-raising. In essence, neg-raising refers to the process of shifting the negative operator to a position ahead of where it ‘should’ be (hence the term raising), in other words to move it from the nested clause to the main clause. However, this is only possible with certain

verbs, commonly referred to in the literature as “neg-raising predicates” (Gajewski 2005). Consider the examples in (5).

(5) a. I do not think that I will be able to make it in time.

b. Sandra did not believe she could play the song perfectly.

Now consider the generally perceived meaning of (5a) in (6a) on the one hand and what it could also be interpreted as – and what is the logically more sound interpretation – in (6b) on the other hand.

b. I am not thinking about whether I will be able to make it in time or not; I have no opinion on this matter.

In other words, neg-raising moves the negative operator into a position that is technically illogical, but is intuitively comprehensive to native speakers. Some speakers would even argue that (5a) is unambiguous and can only mean (6a), despite the fact that (6b) makes more sense as an interpretation from a purely logical and grammatical standpoint.

The literature speaks of Neg-Raising Predicates (NRPs), since neg-raising is connected to certain predicate verbs which allow neg-raising, while all other verbs do not. This assumption can be found largely uncontroversially in the literature regardless of the

author’s approach to and view of the subject of neg-raising. The only somewhat controversial issue occurs in the form of some verbs which may or may not allow neg-raising; this has been pointed out by Collins and Postal (2012: 3; 7) amongst others.

Gajewski (2005: 12) quotes Horn’s (1978) list of NR predicates, assigned to certain semantic classes. It is reproduced below to give a general overview of the verbs relevant for the present discussion on neg-raising; note again that some of the verbs in this list may be considered to not be strict NRPs depending on the speaker’s dialect, and some verbs not listed may be strict NRPs in some speakers’ dialect.

The classes of Neg-Raisers

a. [OPINION] think, believe, expect, suppose, imagine, reckon b. [PERCEPTION] seem, appear, look like, sound like, feel like c. [PROBABILITY] be probable, be likely, figure to

d. [INTENTION/VOLITION] want, intend, choose, plan

e. [JUDGMENT/OBLIGATION] be supposed, ought, should, be desirable, advise (Horn 1978, quoted in Gajewski 2005: 12)

compatibility with neg-raising (see the examples in (7)), and there is cross-linguistic difference between synonymous verbs which are NRPs in one language but not in the other (see the examples in (8)), this argument does not apply fully. Nevertheless, certain tendencies can certainly be observed, such as that most verbs belonging to any of the

five categories listed in Horn’s list above are NRPs and that there are no factive NRPs

(Gajewski 2005: 70-71).

(7) a. I don’t want that to happen again. b. I don’t *desire for that to happen again.

(8) a. I don’t *hope for that to happen again.

b. Ger.: Ich hoffe nicht, dass das jemals wieder passieren wird.

Most speakers would agree that (7a) is a perfectly correct English sentence, while (7b) is not, despite the fact that the verbs want and desire are both part of the semantic category of verbs of intention or volition and are near-synonymous. Therefore, these two verbs offer resistance to a purely semantic reasoning for why some verbs allow neg-raising whilst others do not. (8b) means that the speaker hopes that (that) will never happen again. However, the English sentence in (8a) does not mean the same thing, even though the predicate verb hope is the exact synonym of the German verb hoffen; in fact, these verbs even share the same ancestor. This cross-linguistic variation, which has also been observed by Gajewski (2005: 90) and Horn (1989), again resists a general semantic explanation for the difference between NRPs and non-NRPs.

In the past, it has also been proposed that neg-raising is nothing more than an idiomatic expression, for example by Quine, who refers to neg-raising as a “quirk of English

usage” (1960: 145-146). However, as Napoli (2006: 251) points out, idioms are typically confined to one language, and neg-raising can be observed in many languages (Collins and Postal 2013: 1). Furthermore, since not only negation itself, but also negative quantifiers such as nobody and adverbs such as never are capable of triggering neg-raising, there would either have to be separate idiomatic rules for each particular case or

could form a constituent with the VP headed by the Neg-Raising predicate” (Gajewski 2005: 97). Gajewski goes on to argue that either option finds itself confronted with problems it cannot reasonably explain away; in other words, the theory that neg-raising is nothing more than an idiomatic expression – or a series of idioms – can probably be dismissed.

2.3 Approaches to neg-raising

In the literature, several different approaches towards neg-raising can be found. This subsection will give an overview of the most important and widespread approaches, summarized as syntactic approach and semantic/pragmatic approach respectively. The latter includes Romoli’s (2012; 2013) scalar-implicature based approach towards neg-raising, which aims to point out flaws of the presuppositional approach offered by

Gajewski (2007); the syntactic approach was first proposed by Fillmore (1963) and more recently by Collins and Postal (2012). Finally, we will expand on Napoli’s (2006)

argument touched upon in subsection 2.1 that neg-raising as its own distinct

phenomenon does not exist and that it is merely an instance of the general ambiguity of negation.

2.3.1 The syntactic approach

Fillmore (1963) first proposed the syntactic approach to neg-raising, coining the term negation-raising in his article. He argues that in a neg-raised sentence, the negation is

actually produced in the embedded clause – and is also interpreted in it – but the negation then rises above the predicate and appears in front of it. This approach assumes that the intended meaning of a given neg-raised sentence stems from the

there is a group of verbs – the aforementioned NRPs – which allow neg-raising, while all other verbs do not. The reason behind this difference is regarded to be a purely

syntactic issue, and as such the fact that near-synonymous verbs or cross-linguistic synonyms interact differently with neg-raising is not an issue for the transformational approach. Tovena (2001: 332) adds that the verb also must not be negated already in order for neg-raising to be possible. The neg-raising rule is applied cyclically, which means that the negative particle can move up from one level of an utterance to the next, all the way from the nested clause to the main clause. However, this is only possible if each predicate that is “crossed over” is an NRP. Tovena quotes Lakoff’s (1970: fn. 5)

example “I believe that John wants Bill not to lift a finger to help Irv”, which can be neg

-raised all the way up to “I don’t believe that John wants Bill to lift a finger to help Irv”.

After Fillmore first proposed this theory, it was largely agreed in the 1960s and 70s that neg-raising was indeed a syntactic operation producing sentence pairs which differed in their syntactic structure, but shared the same meaning because the syntactic movement was presumed to have taken place after the original sentence – along with its intended meaning – was already produced. Fillmore (1963) as well as most other defenders of the syntactic approach, such as Horn (1972), Shlonsky (1988) apply a transformational rule to neg-raising; however, some linguists have argued in favor of a non-transformational syntactic account of neg-raising, which can be applied if the author applies no

generative rule at all, but rather utilizes “a framework assuming to be a grammar to be a

model-theoretic system” (Collins and Postal 2012; 1). Among them are Johnson and Postal (1980), Pullum and Scholz (2001) and Collins and Postal (2012).

Collins and Postal’s (2012: 7) non-transformational syntactic approach towards

neg-raising argue that “classical NR is sensitive to syntactic islands”, referring primarily to

wh-islands, and that this fact provides strong evidence against the semantic/pragmatic

the same might apply to classical neg-raising. This piece is especially interesting

because Collins and Postal are among very few linguists in recent times who defend the syntactic approach, and they do so quite vehemently and not without intriguing evidence for their claims.

2.3.2 The semantic/pragmatic approach

The semantic/pragmatic approach towards neg-raising has been the most prevalent approach in recent publications, and arguably even since Fillmore (1963) first proposed the syntactic approach, given publications such as Jackendoff (1971), Bartsch (1973) and Horn (1978). Horn is especially interesting because his earlier works (Horn 1972) argue in favor of the syntactic approach, but he later became one of the most important representatives for the semantic/pragmatic approach (Horn 1978, 1984, 1989, 1993 and more). Other defenders of this approach include Kas (1993), Zwarts (1993), Heim

(2000), and more recently Gajewski (2005; 2007) and Romoli (2012; 2013).

Among the representatives of the semantic/pragmatic approach, Bartsch (1973) is the first to claim a presuppositional approach towards neg-raising. She argues that there is a so-called ‘Excluded Middle’ which speakers assume the listener can intuitively infer to be implied, and listeners infer to be implied. An example for this ‘Excluded Middle’ is given in (9).

(9) a. I don’t believe that Mary has eaten. b. I believe that Mary has not eaten.

c. I have an opinion on whether Mary has eaten. (EXCLUDED MIDDLE)

possible by deeming this presupposition a pragmatic presupposition, which may be fulfilled, but does not have to, in contrast to a semantic presupposition, which has to be fulfilled in order for an utterance to function. This means that if the neg-raising

presupposition condition does not apply, the expression can still be used, but now takes its literal meaning rather than the neg-raised reading.

On the pragmatic side, Horn’s (1989) R-implicature approach is the most widespread and influential. Horn builds his theory upon the Excluded Middle implicature discussed above and introduces what he calls the R-principle. This means that the listener always reads as much as possible into any utterance; this allows neg-raising to be understood as intended by the speaker because the listener will presumably infer a contrary

negation from a contradictory negation. However, Horn notes that this cannot be applied when the difference in literal meaning between a high negation and a low negation is too

big, as “[t]he meaning that would result is too different from the literal meaning“

(Gajewski 2005: 23). The strength of the negation is also a factor. Horn states that with increasing distance between the negation and the negated clause, uncertainty on the side of the speaker pertaining to the negation also increases. Horn calls this the

Uncertainty Principle, and argues that whenever a sentence’s meaning clashes with the

Uncertainty Principle, neg-raising cannot take place because the R-implicature cannot be applied. He goes on to state that this is the case with factives, which explains why there are no factive NRPs.

Additionally, in the semantic/pragmatic paradigm, there is the so-called

199). In the context of neg-raising, this means that the scalar-implicature based

approach argues that neg-raising is used by speakers who adhere to these maxims of communication if it is not less informative than any other possible version of the

utterance and the speaker believes it to be true.

2.3.3 The general ambiguity of negation approach

This is, in a way, a non-approach towards neg-raising. It can be argued that neg-raising as its own independent phenomenon does not exist and is merely a symptom of the general ambiguity of negation. Napoli (2006: 250-251) argues that it may be nothing more than the accidental or ambiguous transformation of a negation from the contrary to the contradictory. In other words, ‘not believe’ is turned to ‘disbelieve’ because it makes no practical difference whether one or the other form is used or understood. Napoli’s (2006: 249) argument that it does not make any practical difference whether John in

Chomsky’s classic example “John does not like mushrooms” actively dislikes

mushrooms or simply does not particularly like them is rather convincing. In Napoli’s

words, “[y]ou will not serve mushrooms to a friend even if he does not particularly like

3

Corpus research

3.1 Methodology

Corpus research can give us great insight into the frequency of usage of certain

phrases, expressions and terms over time as well as in different geographical regions.

Part of the research question of the present paper was ‘how and how often do speakers

use neg-raising?’ In an attempt to answer this question, I conducted corpus research in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (henceforth referred to as COCA), the British National Corpus (BNC), the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), the Corpus of Global Web-Based English (GloWbE) and the British Component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB). The COCA and the BNC are large corpora – consisting of approximately 450 million and 100 million words respectively – of

contemporary English in the respective geographical region, which gives us opportunity to compare the frequency of usage of typical neg-raising phrases between Americans on the one hand and British people on the other hand. The COHA is a vast corpus of

historical American English, comprised of approximately 400 million words from the years 1810 to 2009. This corpus will allow us to look at the development of the

frequency of usage of common neg-raising phrases in American English over the last 200 years. At almost two billion words, the GloWbE is the largest corpus we will look at. It is composed of texts on websites from twenty different English-speaking countries, and as such allows us to compare a vast amount of data from all over the world. Finally, the ICE-GB is a much smaller corpus, comprised of only about one million words, but is nonetheless a decently sized corpus of contemporary British English which allows us

comparisons with the BNC. Unfortunately, due to the construction’s complexity and the

3.2 Corpus study and results

3.2.1 COCA and BNC: geographical data

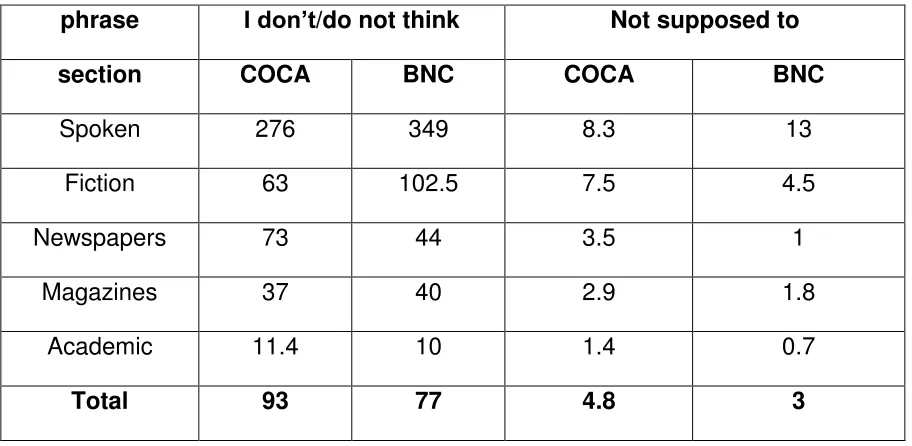

One of the main goals of this corpus study was to compare the frequency of usage of neg-raising between British and American English. For this purpose, I compared the results for the most typical neg-raising phrase, I don’t/do not think, in the COCA on the one hand and the BNC on the other hand. Then, I compared the frequency of usage of the neg-raised phrase not supposed to in the two corpora in order to be able to compare whether there are similarities or differences in frequency of use; the assumption being that if the results for both are similar, conclusions can probably be drawn and applied to the phenomenon of neg-raising as a whole in British and American English; whereas, if the results were to differ significantly from each other, any conclusions may only be applied to a specific phrase rather than to neg-raising in general. Table 1 details the results, normalized to frequency of occurrence per one million words for both corpora in order to simplify comparisons. In the case of the phrase I don’t/do not think, not only were both the contracted as well as the non-contracted form taken into consideration; additionally, the results of searching for the phrase I don’t/do not think so were

Table 1 Results for I don’t/do not think and not supposed to in COCA and BNC

As table 1 shows, the frequency of usage of both neg-raising phrases I don’t/do not think and not supposed to is significantly higher overall in American English than in British English. This result is very interesting, as there is nothing in the literature or intuitively that would suggest either variety to be more or less likely to utilize neg-raising.

Considering the vast size of both corpora, the results can probably be regarded as rather representative of each variety, making this significant difference all the more intriguing. A closer look at the different sections of the corpora makes this issue yet more interesting: in the largest category in both corpora – Spoken -, the phrase in question actually occurs significantly more often in the BNC (349 occurrences per one million words) than it does in the COCA (276 occurrences per one million words). This is a difference of almost a third of total occurrences, and a very similar difference in favor of the British corpus can be observed in the section Fiction, with 102.5 occurrences per one million words in the BNC and only 63 occurrences per one million words in the COCA; skimming the individual results in Fiction led to the conclusion that the vast majority of these cases are to be found in dialogues, which are of course fictional reproductions of spoken conversation and could as such be regarded as a category

phrase I don’t/do not think Not supposed to

section COCA BNC COCA BNC

Spoken 276 349 8.3 13

Fiction 63 102.5 7.5 4.5

Newspapers 73 44 3.5 1

Magazines 37 40 2.9 1.8

Academic 11.4 10 1.4 0.7

similar to Spoken. As such, the comparable distribution makes perfect sense. In fact, the

only relevant categories in which the frequency of I don’t/do not think is higher in the

COCA than it is in the BNC is in Newspapers (73 versus 44 in the BNC) and in

Academic (11.4 versus 10 in the BNC), and it occurs rarely in the latter category in both corpora; additionally, this difference is comparatively small to begin with. The difference in newspapers, however, is remarkably larger and suggests a difference in journalistic style between Americans on the one hand and the British on the other hand; perhaps American newspaper journalists tend to use more colloquial and personal language, or perhaps they simply include more direct quotations in their articles than their British colleagues do. The rather low frequency of the phrase in Academic context can be explained by the fact that the phrase in question is relatively colloquial and therefore does is not very compatible with academic language; it is also a rather vague phrase which suggests uncertainty. While expressing uncertainty is necessary in certain

contexts in academic language, this task is typically accomplished through the usage of other phrases specifically suited for the academic context.

results in the COCA and is completely nonexistent in the BNC. This difference between very little and none at all is probably not significant and can be attributed to the fact that the COCA is comprised of almost five times as many words as the BNC. However, it is interesting that the phrase not supposed to is so entrenched that its ‘regular’ form appears to be all but extinct in both varieties. When searched for in the COHA,

supposed to not again leads to very little results, namely a single result each in the years

1977, 1995 and 2004. The 1977 result is taken from an article in a magazine, while both the 1995 and 2004 results originate from works of fiction. In other words, the phrase supposed to not has been extremely uncommon in American English at least since

1810, and if it does occur it does so in writing. We will take a closer look at the COHA and developments in the frequency of use of certain neg-raising phrases in the following subsection.

3.2.2 COHA: historical data from 1810-2009

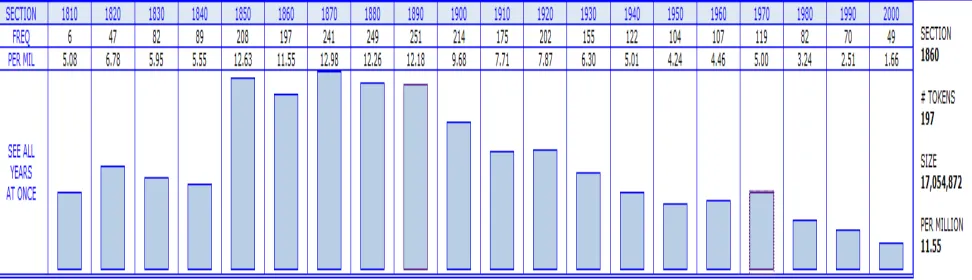

In this subsection, we will investigate the frequency of use of the two phrases previously looked at in American English over the last 200 years. For this purpose, the COHA was used. Figure 1 shows a largely consistent increase in frequency of use of the phrase I

don’t think in American English from 1810 to 2009. If we regard the data for the

democratization of society and the possibility of neg-raising being utilized as a means of politeness.

Figure 1 Frequency of I don’t think in American English between 1810 and 2009

Figure 2 Frequency of I do not think in American English between 1810 and 2009

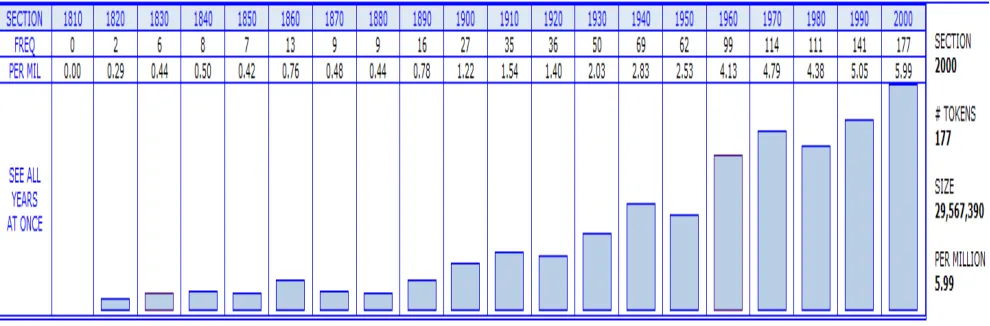

However, a look at figure 3 reveals that there are at the very least two phrases typical for neg-raising which have experienced a marked increase in frequency of usage in

American English over the last 200 years, according to the COHA: the phrase not supposed to has, in fact, increased in usage even more dramatically and consistently

than I don’t/do not think. Searching for supposed in the COHA leads to a more or less even distribution over the years, while searching for suppose even results in a gradual decrease of frequency. These results suggest that the popularity of the words suppose or supposed without the neg-raised negation is not responsible for the observed

While not entirely conclusive, the consistent significant increase in frequency of both phrases strongly suggests that neg-raising has been enjoying increasing popularity in American English over the last 200 years. This is very intriguing and deserves a more detailed investigation, as well as a comparison with historical corpus data of British English. Unfortunately, these investigations would exceed the scope of the present paper; the data presented in this section, however, does offer very interesting

possibilities for further research into historical development of neg-raising as well as a closer investigation of potential reasons behind this apparent increase. The latter issue is also discussed in section POSSIBLE REASONS FOR NEG-RAISING of the present paper.

Figure 3 Frequency of not supposed to in American English between 1810 and 2009

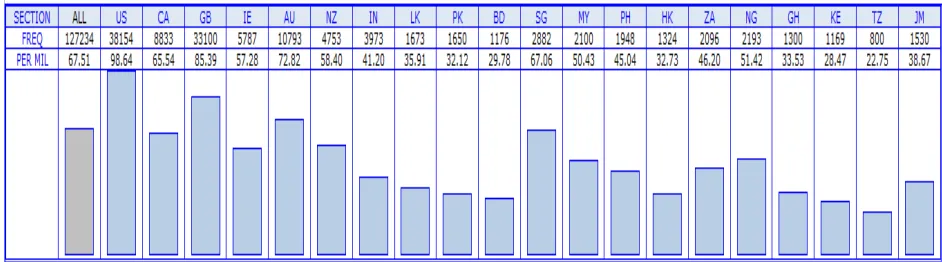

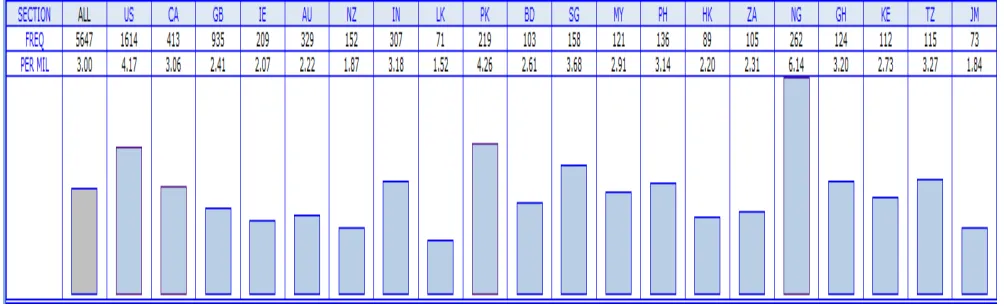

3.2.3 The GloWbE: an international web-based comparison

Searching for the phrase I don’t think in the Corpus of Global Web-Based English, which is comprised of 1.9 billion words taken from 1.8 million web pages in 20

Figure 4 Frequency of I don’t think in the GloWbE

to why Singaporeans use neg-raising frequently, as forms of politeness are very important in Asian languages. In regards to Ireland and New Zealand, I refuse to even guess at possible reasons; I would like to point out, however, that these two countries have the smallest populations of all the inner circle variety nations. Why or how this might play a role, however, cannot possibly be explored in this paper; however, this issue could allow for further research into the matter.

Intriguingly, entering the phrase not supposed to into the GloWbE leads to very different and thus unexpected results, as can be seen in figure 5.

Figure 5 Frequency of not supposed to in the GloWbE

While the overall numbers are significantly smaller than those for I don’t think– which is consistent with our previous findings in the other corpora – the total numbers are still high enough to be considered statistically relevant due to the vast size of the GloWbE. The graph shows a vastly higher frequency in Nigerian English than it does in any other variety; in fact, its frequency is more than twice as high as the average frequency across all twenty national varieties. The only other varieties that are significantly above the average are Pakistani English, American English and – to a lesser degree –

significantly below the average, especially New Zealand and Irish English. The latter two also have lower frequencies in usage of I don’t think, as previously mentioned, which means that our previous observations are somewhat confirmed in this regard. American English being above the other inner circle varieties also corresponds with our previous findings; however, the rest of figure 5 contradicts our previous data quite profoundly. The extremely high frequencies of occurrence in Pakistani and especially Nigerian English are particularly intriguing; perhaps there are certain cultural or cross-linguistic reasons at work here, such as an expression in the native languages of these peoples which shares a similar structure with not supposed to, making it an attractive phrase for native

speakers of the languages in question. However, any possible reasons behind this can only be guessed at in this paper. The fact that the phrase not supposed to is used less

frequently in all inner circle varieties except for North America (where Canada’s

frequency is barely above the average while that of the US is about 30% above the average) is also intriguing. Due to the nature of the GloWbE data, it is difficult to make any conclusions of overall usage based only on web-based data; however, this

difference is significant enough to be taken under closer scrutiny. Based on only this data, it seems that US Americans specifically use the phrase very frequently, and the somewhat higher frequency of Canadian usage compared to frequency in the other inner circle varieties could perhaps be explained through the geographical and cultural proximity of Canada to the US. However, why US Americans would use this phrase significantly more often in web-based texts than their British, Australian and New Zealand contemporaries can only be guessed at; there may be cultural reasons behind this discrepancy, or it can be traced back to a qualitative difference in sources of the texts offered by the GloWbE. Unfortunately, these sources cannot be examined and as such, a conclusive argument cannot be given in the present paper. Yet again, further research into the matter may be useful.

3.2.4 ICE-GB: further data on contemporary British English

The ICE-GB, as previously mentioned, is much smaller than the other corpora

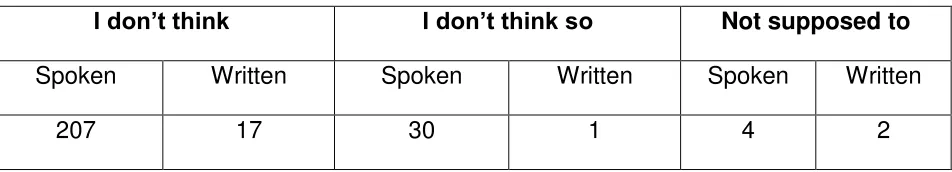

British English. Among these one million words, the phrase I don’t think occurs 224 times. The phrase not supposed to only occurs six times in total in ICE-GB. Table 2 offers a detailed breakdown of occurrences.

Table 2 Frequency of I don’t think and not supposed to in the ICE-GB

I don’t think I don’t think so Not supposed to

Spoken Written Spoken Written Spoken Written

207 17 30 1 4 2

The occurrences of I don’t think so are listed as they need to be subtracted from the total frequencies of I don’t think, as I don’t think so is not neg-raised. This means that we end up with 177 occurrences of spoken I don’t think as part of a neg-raised sentence and 16 occurrences of written I don’t think as part of a neg-raised sentence in ICE-GB. These findings are consistent with my previous findings in the BNC detailed in table 1. In both corpora, I don’t think occurs significantly more frequently in spoken English than it does in written English, and the same is true for not supposed to. I don’t think also generally occurs much more frequently than not supposed to does, which is again a result consistent between both British corpora.

3.2.5 Conclusion

Due to the structural complexity of neg-raising, the present corpus study has looked at two typical neg-raising phrases: I don’t/do not think and not supposed to. Data from COCA, the BNC, the GloWbE and ICE-GB suggest that in contemporary English,

Americans use these phrases – and therefore presumably neg-raising – more frequently than other varieties of English. However, some anomalies which contradict this

GloWbE show that all inner circle varieties use the latter phrase more frequently than all outer circle varieties except for Singaporean English. These results are quite intriguing and could be an interesting subject for future studies. An examination of the same phrases in the COHA has led to the conclusion that both phrases have enjoyed an almost entirely consistent increase in usage; however, this can be at least partially explained by the fact that the percentage of spoken texts compared to written texts also increases gradually from 1810 to 2009 in the COHA, and these phrases are more typical for spoken than for written English; this last argument is supported by the results of the COCA, BNC and ICE-GB, which all show significantly higher frequencies in spoken than in written English.

4

Possible reasons for neg-raising

This final section of the present paper will discuss possible reasons for why speakers use neg-raising. These will be mostly my own ideas, with additional arguments or support from the literature.

face-saving act in favor of the listener by implying that the speaker’s statement – which follows in the nested clause – is not absolute, but merely a belief the speaker holds, but

is uncertain of. Napoli (2006: 251) refers to this phenomenon as “an intention of politeness conducive to forms of understatement”.

(10) a. I don’t think your statement is correct. b. I think your statement is incorrect.

This argument is certainly intriguing; however, I would like to propose a

counterargument. In political speeches, neg-raised phrases can frequently be heard, such as the following example taken from a speech by US President Barack Obama.

(11) I don't think that's a satisfactory response. (obamaspeeches.com)

An instance such as (11) is interesting because it is highly unlikely that Obama, or indeed any politician, would use neg-raising with the goal of politeness. That is not to say that high-ranking politicians or the writers of their speeches intend to be impolite; but politeness always implies a certain amount of uncertainty, as discussed above, and the last thing the President of the United States of America would want to be perceived as is

uncertain of himself. As such, the reason for Obama’s usage of the neg-raised phrase I don’t think and the countless other incidents of neg-raising in political speeches has to have reasons behind it which are not connected to politeness. An argument could be made, especially in a case such as I don’t think, that the phrase is simply so entrenched that the politician in question may not even have consciously realized that they used it, or the alternative did not even occur to them. However, I would argue that it is more likely that neg-raised phrases are used quite consciously and purposely in political speeches for another purpose: due to the oral performative factor of such speeches, intonation can and will be used by any decent speaker to support and strengthen their points. Using a neg-raised phrase, especially one that includes a first-person personal pronoun – regardless of whether it is I or we – allows the speaker to put great stress on

uncertainty in the listener. My argument is therefore that in speeches, neg-raising may be used not to imply uncertainty but rather than to imply certainty through the application of stress on the correct words. However, this does not mean that neg-raising may not still be used to imply uncertainty in other contexts; this proposition merely implies that the application of neg-raising and its intended meaning is dependent on context, and is therefore a pragmatic issue.

Tovena (2001: 339-340) argues that “computational considerations” may be interpreted

as the “psychological motivation” for neg-raising: the switch from the contradictory to the contrary takes place because if something is not proven to be true, humans consider it false simply because this way, the information is easier to digest. Rather than having to

“store negative information”, one can simply decide for each piece of information

whether it is true or false, which at the same time allows one to ignore the complex issue

of “negative facts”. Tovena argues that “the lower negation is logically stronger” and that

therefore effect of said negation is maximized which allows a maximization of

interpretable inferences from both the information as well as the assumptions inherent in the negated phrase. She cites Jackendoff’s (1969) argument that the initial position of the negation is implied regardless of its actual realization, and argues that it supports his argument because the neg-raised verison therefore also includes the information of the

‘standard’ un-raised form. Tovena supports her argument of neg-raising as a deeper cognitive phenomenon – rather than one bound to particular languages – by citing Horn (1978) who claims that its use has been recorded even in Esperanto, despite the fact that its prescriptive grammar explicitly dictated that neg-raising may not be used (meaning that it must not be used).

Another argument which has occurred to me over the course of writing this paper is that in regular conversation, the most important piece of information – namely whether there

will be a negation in a speaker’s response to another speaker’s statement or not – will occur sooner in a neg-raised sentence than it does in the unraised equivalent.

the piece of information that the speaker disagrees with him or her sooner than if the utterance had not been raised. (10) works as a good example for this idea: in (10a), the raised version, the negative particle occurs almost at the very beginning of the

5

Conclusion

The present paper has dealt with the issue of neg-raising. The research question for this paper was what is negation raising, how and how often do speakers use it, and what is its purpose?

We have started this discussion in section 2 by establishing a theoretical backdrop by giving an overview of the most widespread approaches towards neg-raising. In section 3, we looked at corpus data from the following corpora: BNC, COCA, COHA, GloBwE and ICE-GB. We compared results of frequency of usage for two typical neg-raising phrases between the corpora, allowing for comparison of different varieties of English as well as changes in the usage in American English over the last 200 years. This research has led to some very intriguing revelations, most notably the apparent increase in usage of neg-raising phrases in American English over the last 200 years and the observation that inner-circle varieties appear to be more likely to neg-raise than outer circle varieties, apart from some rather inconclusive anomalies that do not adhere to this theory. Finally, in section 4 we discussed reasons as to why speakers may use neg-raising; while this has not led to an entirely conclusive answer, it has provided some thought-provoking

ideas and the general stance of ‘it depends on context’, which would imply that neg -raising is a pragmatic phenomenon after all. Since several questions could not be answered conclusively, and more questions indeed came up in the composition of this paper, there is plenty material for further research to be found in the present paper; hopefully, other researchers will conduct this research as neg-raising is a fascinating, yet complex topic and deserves even more attention than it has been receiving.

6

references

Ayer, Alfred J. 1952. "Negation." The Journal of Philosophy 49/26, 797-815.

Bartsch, Renate. 1973. "Negative transportation” gibt es nicht." Linguistische Berichte 27/7.

Beukeboom, Camiel J.; Finkenauer, Catrin; Wigboldus, Daniel H. J. 2010. “The Negation

Bias: When Negations Signal Stereotypic Expectancies”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99/6, 978-992.

Collins, C.; Postal, Paul. 2012. “Classical NEG-raising”. Unpublished manuscript. Available on LingBuzz. Lingbuzz/001498.

Davies, Mark. (2004-) BYU-BNC. (Based on the British National Corpus from Oxford University Press). Available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/bnc/ (18 January 2014). Davies, Mark. (2008-) The Corpus of Contemporary American English: 450 million

words, 1990-present. Available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/ (18 January 2014).

Davies, Mark. (2010-) The Corpus of Historical American English: 400 million words, 1810-2009. Available online at http://corpus.byu.edu/coha/ (18 January 2014). Davies, Mark. (2013) Corpus of Global Web-Based English: 1.9 billion words from

speakers in 20 countries. Available online at http://corpus2.byu.edu/glowbe/ (18 January 2014).

Davis, Wayne A. 2011. “’Metalinguistic’ negations, denial, and idioms”. Journal of Pragmatics 43, 2548-2577.

Fillmore, C. 1963. “The position of embedding transformations in grammar”. Word 19, 208-231.

Gajewski, Jon Robert. 2005. “Neg-raising: Polarity and presupposition”. Diss. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Gajewski, Jon Robert. 2007. “Neg-Raising and Polarity”. Linguistics and Philosophy 30, 289-328.

Giora, Rachel. 2006. “Is negation unique? On the processes and products of phrasal

negation”. Journal of Pragmatics 38, 979-980.

Grice, Paul. 1975. “Logic and conversation”. In Davidson, D.; Harman, G. (eds). The Logic of Grammar. Encino, CA: Dickenson, 64-75.

Heim, Irene. 2000. “Degree operators and scope”. In Proceedings of SALT X.

Horn, Laurence. 1972. “Negative transportation: Unsafe at any speed?”. Proceedings of CLS 7, 120-133.

Horn, Laurence. 1978. "Remarks on neg-raising." Syntax and semantics 9, 129-220. Horn, Laurence. 1984. "Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inference: Q-based and

R-based implicature." Meaning, form, and use in context, 11-42.

Horn, Laurence. 1989. A Natural History of Negation. Chicago :The University of Chicago Press.

Horn, Laurence. 1993. "Economy and redundancy in a dualistic model of natural language." Sky, 33-72.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1969. “An interpretive theory of negation”. Foundations of Language 5, 218-241.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1971. “On some questionable arguments about quantifiers and

Johnson, David E.; Postal, Paul. 1980. Arc pair grammar. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kas, Mark. 2003. “Essays on Boolean functions and negative polarity”. Ph. D. thesis, University of Groningen, Dissertations in Linguistics 11.

Kjellmer, Göran. 2000. “No Work Will Spoil a Child”. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 5/2, 121-132.

Lakoff, George. 1970. "Pronominalization, negation, and the analysis of adverbs." Readings in English transformational grammar, 145-165.

Napoli, Ernesto. 2006. “Negation”. Grazer Philosphische Studien 72, 233-252. Obamaspeeches.com. World AIDS Day Speech - 2006 Global Summit on AIDS.

http://obamaspeeches.com/095-Race-Against-Time-World-AIDS-Day-Speech-Obama-Speech.htm

Pullum, Geoffrey K.; Scholz, Barbara C. 2001. "On the distinction between model- theoretic and generative-enumerative syntactic frameworks." Logical aspects of computational linguistics. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 17-43.

Quine, W.V.O. 1960. Word and Object. Cambridge (MA): MIT.

Romoli, Jacopo. 2012. Soft but Strong: Neg-raising, Soft Triggers, and Exhaustification. Diss. Ph. D. thesis, Harvard University.

Romoli, Jacopo. 2013. “A scalar implicature-based approach to neg-raising”. Linguistics and Philosophy 36, 291-353.

Shlonsky, Ur. 1988. “A Note on Neg-Raising”. Linguistic Inquiry 19/4, 710-717. The British Component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB). University

College London. http://www.ucl.ac.uk/english-usage/projects/ice-gb/ (18 January 2014).

Tottie, Gunnel. 1980. “Negation and Ambiguity”. In Jacobson, Sven (ed). Papers from the Scandinavian Symposium on Syntactic Variation. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 47-62.

Tovena, Lucia M. 2001. “Neg-Raising: Negation as Failure”. In Hoeksema, Jack;

Rullmann, Hotze; Sanchez-Valencia, Victor; van der Wouden, Ton (eds). Perspectives on Negation and Polarity Items. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publisher Co, 331-351.