Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Representations of Development in 19

th

and

20

th

Century indonesia: A Transport History

Perspective

Howard Dick

To cite this article: Howard Dick (2000) Representations of Development in 19

thand 20

thCentury indonesia: A Transport History Perspective, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies,

36:1, 185-207, DOI: 10.1080/00074910012331337833

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331337833

Published online: 21 Aug 2006.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 96

View related articles

REPRESENTATIONS OF DEVELOPMENT

IN 19

THAND 20

THCENTURY INDONESIA:

A TRANSPORT HISTORY PERSPECTIVE

Howard Dick*

University of Melbourne

Contemporary debate in Indonesia over ‘people’s economy’ and ‘globalisation’ recalls the vigorous 1950s debate over ‘dualism’. Taking as a case study the rise and eclipse of railways, this paper argues that the colonial phenomenon of dualism can with hindsight be reinterpreted as a phase in a previous cycle of globalisation. However, economic history has overlooked the remarkable vitality of the small-scale transport sector. Focus on the small-scale sector highlights the inadequacies of familiar paradigms and suggests the need to reconceptualise long-term socioeconomic change. This analysis has important implications for responses to the current wave of globalisation and how they may be manifest in a more democratic post-Soeharto Indonesia.

INTRODUCTION

The terms ‘formal sector’ and ‘informal sector’ stereotype a more complex reality, but they serve to distinguish between a highly structured, capital-intensive corporate sector, which thrives in a stable, low-risk environment, and a much more labour-intensive, family- or household-based sector which has the flexibility and resilience to survive in a very unstable and uncertain environment. At the end of the 1990s, as in the mid 1960s, the formal sector found itself struggling in a much harsher post-crisis environment, while small-scale enterprises again prospered and multiplied. The aim here is not to revive the old chestnut of whether Indonesia is in fact a dualistic economy and society, which is a crude proposition, but to explore ways in which perceived dichotomies, between small scale and large scale, between local and global, continue to influence thinking and policy.

At times of crisis and regime change ‘other things’ do not hold constant. Familiar assumptions need to be re-examined. One approach is to set the immediate past in historical perspective. Revival of the formal sector under the New Order resembled an earlier colonial phase of corporate capitalism that began around the 1890s and lasted until the 1930s. However, it contrasted sharply with the intervening period. In the 1930s, as the modern or ‘formal’ sector of the colonial economy reeled under the shock of the world depression, the informal sector thrived and then continued to expand through the Japanese occupation, the Revolution and the first two decades of independence. Post-New Order Indonesia, economically weak and hesitantly democratic, shows some of the features of the 1950s when the colonial paradigm was under challenge.

Given the new relevance of the 1950s experience, this paper seeks to revisit several ‘ghosts’ from that time that continue to haunt debates about the nature of capitalism and development in Indonesia. The first of these is dualism. It was never a theory but, like the more recent term ‘globalisation’, a codeword.1 It denoted—and oversimplified—an

The following analysis is partly historical and partly interpretive. The first part of the paper takes as a case study a story about the rise and eclipse of Java’s railways, looking first at their impact around 1890, when they were a leading edge of formal sector expansion, and then over a century tracing their long-term decline in the face of competition from small-scale land transport. The second part discusses some of the familiar paradigms by which this story has in the past been caricatured, specifically dualism, the lack of a firm-based Javanese response to modernisation, and shared poverty, and draws out some of the implications of this economic history for the current debate over globalisation.

A TALE OF TWO SECTORS

2The Intrusion of Railways

Java was the only territory of Southeast Asia to experience the full force of the global industrial revolution of the 19th century. Around 1800 it had

been a set of loosely connected economies and societies held together by a ramshackle colonial state. By 1900 it was a sophisticated agro-industrial economy integrated by overlapping networks of telegraphs, telephones, railways, narrow-gauge tramways and good roads. Nowhere in Southeast Asia could boast better infrastructure (Dick 1992). Elsewhere in East Asia, only Japan could compare.

Railways decisively shifted goods movement away from the main rivers. Running more or less parallel to these former arteries of commerce, railways were faster and more reliable. The much cheaper freight by river prahu was offset by risks of pilfering and water damage (OMW 1907). Export commodities for which quality mattered therefore shifted to rail. Sugar was particularly suited to rail because it was bulky, it could be consolidated into wagon loads, and the volume of traffic justified rail spurs to the actual mills. By 1903 the average daily river traffic into Surabaya was 110 prahu of around 700 tonnes capacity, which may be compared with the seasonal average daily sugar carriage by rail of 6,000 tonnes (OMW 1907; Osten 1930: 8).

Maatschappij, the Netherlands Indies Railway Company) did indeed reduce its tariffs across the board from 1 January 1892.

The uncompetitiveness of rail freight vis-à-vis road had two contributing causes. First, as a line-haul operation, shipment by rail incurred feeder and transhipment costs at both ends of the journey, which had also to be reckoned in the door-to-door calculus. The paperwork involved in shipment by rail and the greater risk of damage or leakage of fragile or liquid goods might also be taken into account. In the case of traffic between Jakarta and Bandung, Chinese importers sent low volume but heavy goods such as screws, nails, metalware, paint, linseed oil and soap by ox-cart (grobak); iron pots and pans were said to be carried 50% more cheaply than by rail.

Secondly, rail competition brought about considerable reduction in the costs of competing modes. Local carters seem to have charged what the traffic would bear in the light of railway tariffs. The Resident of Japara reported that in competition with the narrow-gauge tramway small local carts (karretjes) had reduced charges to only one-third of their previous level, despite which their number continued to increase. Elsewhere charges probably fell by rather less, but still roughly matched those for rail before calculation of feeder and transhipment costs. The Resident of Pasuruan explained that the 15 kilometres from Pasuruan to Grati by third-class rail cost 17 cents per person without accompanying goods, whereas three to five women with baskets could share a small cart for 50 to 60 cents, or around 17 cents per person with accompanying goods and direct to their village.

sold back in Bagelen in the same manner. One return trip would take about 20 days and yield just enough profit to live on. As a subsistence activity, such carrying and trading was quite sophisticated and might be likened to the operation of small interisland prahu.

The rate at which passenger traffic shifted to rail was also impeded by high fares. In May 1891 the Resident of Surakarta described the rates of the NISM as ‘neither cheap nor fair’. His concern was not with the rates charged for export crops, which very quickly shifted to rail, but with those for Indonesian passengers and in particular petty traders. He observed that few passengers travelled with goods in excess of the free allowance:

The native, who places no value on time and expects much more for his few coins than quick transport, still goes much on foot, even carrying his goods himself. Besides, the transport of the goods by rail is much too expensive for him, for the transport costs often amount to more than the value of the goods (KV 1892: C5).

The Netherlands Indies Railways and the State Railways therefore seem to have had only a marginal impact on petty trade. Narrow-gauge tramways, by contrast, specialised in local passengers and market traders, and set timetables to fit in with the timing of local markets.

In the long run, market forces thus established a dynamic equilibrium between rail and ‘traditional’ modes of transport. The initiative lay very much with the railways and tramways, state and private, which by trial and error adjusted the level and structure of passenger fares and freight rates to achieve the most profitable mix of traffic. Other modes had to make the most of the opportunities that were left. Railways came to dominate longer distance freight and passenger movement, while road-based traffic remained competitive over shorter distances, especially in serving the village economy.

was more lively traffic between villages and local markets. On balance the number of horse-drawn vehicles continued to increase. This applied particularly to pony-carts suited to carrying both passengers and small quantities of accompanying goods.

Secondly, some ‘traditional’ vehicles were forced into ‘down market’ niches. River prahu, for example, lost most of the long-distance trade except in village produce such as local sugars, padi and palawija, or very low-value items such as wood, firewood, charcoal and fruit, especially coconuts (OMW 1907). Even today, traditionally built wooden prahu are still used on the lower reaches of the Brantas and Solo rivers, larger ones for sand and gravel and smaller ones for local trade across the river where there are no nearby bridges. Similarly with grobak: since the 1830s, when such carts had been requisitioned, their mainstay had been cane transport from fields to the factory. As the rail network intensified, however, and mills laid mini-gauge rails into the fields, this demand collapsed, except among older and smaller mills, none of which survived into the 1920s. In the lowland plain, carts were relegated to the transport of low-value local goods which were either heavy, such as bricks and tiles, or of very large volume, such as wooden or bamboo furniture, timber or firewood. In the highlands, ox-carts were better able to hold their own until the era of motor transport. For reasons of terrain, pack horses and even porters also continued to be used.

Thirdly, there was some evidence of innovation in the kind of service provided by small-scale indigenous transport. For example, in 1904 the Resident of Mojokerto in the Lower Brantas reported that pony-carts (dokar) were being used like omnibuses, not for single hire, but picking up and putting down passengers along the road at very low fares (OMW 1907). While this might seem a small thing, conceptually it marked a breakthrough to the stage of common carrier.3 Significantly, the

breakthrough occurred a generation before motor buses and three generations before the ‘Colt revolution’ of the 1970s. In other words, the organisational breakthrough appears to have preceded the generally recognised technological one, confirming the flexibility and adaptability of the small-scale indigenous sector.

The Automobile Age

automobiles were still hardly to be seen outside the main coastal cities (Knaap 1989: 86–7). By 1929 the number of vehicles had increased to 45,000, and imports were over 10,000 units in both 1928 and 1929. Imports of trucks and buses, which began to be significant at the end of World War I, were also running at a high level. The demand for vehicles on Java was so high that in 1927 General Motors made the decision to locate its new assembly plant not in Singapore but in Jakarta.

Railways began to feel the spur of road competition in the 1920s.4 In

East Java, for example, by 1927 there were 35 bus owners based in Surabaya with a fleet of 200 vehicles, for the most part deployed along the same busy corridors to and from outlying market towns. Most of these operators owned no more than a few buses, but one large Chinese firm (Tan Luxe Omnibus Service) owned 65; by 1930 this Tan Luxe fleet had increased to 250 buses operating across a network of 625 kilometres. The OJS (note 4) attributed this upsurge of road competition to several factors. First, rail tariffs had not been adjusted in line with the deflation that had occurred since the end of the boom in 1920. Second, newly imported buses had become very cheap—only f3,000 for a vehicle able to carry around 20 passengers–and, with few overheads, could carry passengers for as little as one cent per kilometre and still make a modest profit. Third, the quality of bus service was better, with more frequent departures and willingness to stop on demand anywhere along the road, which reduced the need for passengers to walk or to pay for other transport to get to and from the station.

Small-scale entrepreneurship in land transport did not emerge out of nothing. It grew out of the services long provided by carts, relying mainly upon animal power. The tiny European community owned half the

TABLE 1 Number of Motor Vehicles, Java and Madura, 1900–96a

1900 1910 1929 1940 1966 1996 Vehicles 15 1,000 45,000 58,000 140,000 1,850,000

aTo 1940 including motorcycles.

colony’s private automobiles, which were luxury items, and a third of the motorcycles, but only 7% of commercial vehicles (Knaap 1989). Of this last category, Indonesian and Chinese owners held almost equal shares. Local transport was an industry that local people well understood. They had only to master and adapt the mechanics and navigation of motor vehicles, a challenge they embraced with enthusiasm.

In the face of this vigorous challenge, railways sought government protection from bus competition, citing their public service role and pointing to the burden of high overhead costs. The Dutch Motor Traffic Act of 1924 established a precedent for licensing and regulation, but the government dithered. On the one hand was the alliance of colonial capital and the state, not least as the main railway owner, pressing strongly for regulation. On the other was the public interest in cheap fares. Amidst ongoing controversy the Road Traffic Act (1933) came into effect on 1 January 1937. Thereafter along main highways buses and trucks were allocated to set routes, for which operators and capacity were licensed and minimum tariffs and other restrictions set by decree. Implementation was delegated to provincial and local government. This system, with all its powers of patronage and discrimination, is still in force, administered by the Directorate General of Land Transport.

As a matter of survival, rail and tramway companies had also to adopt commercial strategies. One strategy was to start up subsidiary bus services as extensions of and feeders to the rail network. Another was to reduce fares and improve frequencies. Road competition also forced railways to restructure their business towards freight. Assisted by the rapid expansion in the output of sugar, rail freight of 16 million tonnes in 1929 much surpassed the 1920 peak of 12 million tonnes (table 2).

Despite the erosion of rail traffic, especially around the main cities, on the eve of World War II Java remained pre-eminently a rail-based society. On 1 January 1941 the whole of Java and Madura could boast

TABLE 2 Rail Freight, Java and Madura, 1911–96

1911 1920 1929 1935 1939 1960s 1996 Freight

(million

tonnes) 8 12 16 5 8 2 7

only 58,000 motor vehicles, including 10,000 motorcycles, which by contemporary standards was insignificant (table 1). Nevertheless, the trends were against rail. In terms of passengers, Java’s railway and tramway companies never surpassed the peak carriage of 166 million in 1920 (table 3). From 130 million in 1929, numbers collapsed during the 1930s. In 1939 only 76 million passengers were carried, no more than in 1911, although the network was more extensive and the average journey longer. Rail freight also collapsed during the depression, falling from 16 million tonnes in 1929 to just 5.4 million tonnes in 1935. By 1939 tonnage was still only half the level of 1929 and, as in the case of passengers, no more than that carried in 1911–12.

The Cycle Revolution

During the 1930s the Indonesian population found in the bicycle a cheap and flexible mode of road transport. The large yen devaluation of December 1931 made imported Japanese bicycles cheap enough to become an item of mass consumption. In expanding cities like Jakarta and Surabaya, they were a means to commute to work without having each day to pay precious cents in public transport fares. Factories installed long rows of cycle racks. With small adaptations, the bicycle was also found to be a very efficient means of carrying small quantities of goods from village to market. The bicycle became for Indonesians what the car was to Europeans. Between 1931 and 1940, 240,000 bicycles were imported to Indonesia, which may be compared with the 1940 total of 88,000 motor vehicles (58,000 for Java and Madura) (Knaap 1989). Photographs taken in the 1930s, especially in the main cities, show large numbers of bicycles sharing the street with motor vehicles. After independence the bicycle became ubiquitous, almost epitomising the new era of personal freedom. As late as 1970 the former revolutionary capital of Yogyakarta was still a

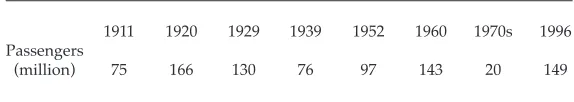

TABLE 3 Rail Passengers, Java and Madura, 1911–96

1911 1920 1929 1939 1952 1960 1970s 1996 Passengers

(million) 75 166 130 76 97 143 20 149

city of bicycles and pedicabs, with scarcely a car to be seen and only a few motorcycles. In rural Java the bicycle is still an important means of transport.

During the Japanese occupation of 1941–45, bicycle technology gave rise to a new public transport vehicle, the becak or three-wheeled pedicab. The first rather heavy and unwieldy prototypes appeared in the late 1930s—a decade of innovation in public transport—and seem to have developed from the more common goods delivery vehicles (Robinson 1952). After the military requisitioned all motor vehicles in 1942, a lighter and more manouevrable type of becak gained popular acceptance, competing against the well established pony-carts, which were dependent upon a regular supply of feed. Owners were mainly Hokkien Chinese, who controlled the bicycle trade, but drivers were invariably indigenous Indonesians, often villagers who had migrated to the city in search of employment. Although the heavy work of pedalling was regarded as demeaning by educated Indonesians, the tukang becak themselves were a tough and independent band of urban dwellers who claimed the cities and towns of Indonesia as their own territory.

Under the New Order, rising real incomes saw the bicycle give way to the Japanese-made motorcycle as popular individual transportation. In the early 1960s motorcycle numbers were growing at a rate of about 10% per annum, but as late as 1966 only 216,000 were registered, fewer than the number of bicycles in 1941. By 1996, however, there were 6.5 million in Java—two-thirds of all registered motor vehicles—and new motorcycles were being assembled locally at the rate of a million each year (BPS 1997). Automobile numbers grew more slowly, from 140,000 in 1966 to almost two million by 1996. In the cities the extraordinary growth in motor traffic resulted in the bicycle being marginalised—not least because cycling was now so dangerous. In Jakarta during the 1970s the reign of the becak was forcefully brought to an end, setting an example for restrictions to be imposed in other main cities.

The Railways in Eclipse

rail freight to recover to 6.7 million tonnes, but this was still no better than the depression levels of the 1930s.

In passenger traffic, the 1950s were the Indian summer of the railway system. Recorded passenger movement increased from 97 million in 1952 to a peak of 143 million in 1960 (table 3). Assuming that fare evasion was much more rife and at least 15% of traffic, this would have equated to the record carriage of 1920, albeit from a much larger population. Yet by the mid 1970s, in the face of vigorous bus competition, passenger traffic had collapsed to only 20 million. Java’s passenger traffic was booming but rail patronage was in decline. Rehabilitation of Jakarta’s metropolitan network and introduction of fast inter-city trains helped to revive patronage from 60 million in 1991 to 149 million in 1996 (table 3), impressive enough by prewar standards, but at 1990s levels of population and mobility no more than a niche operation.

The passenger business lost by rail was captured by air and road transport. By the 1950s government officials and businessmen could afford to fly, even within Java, and by the early 1990s there were hourly shuttle flights between Jakarta and Surabaya. The general public travelled by long-distance bus. During the 1970s there was a boom in overnight long-distance bus services, which competed in quality of service, offering soft seating, air-conditioning and taped music. Every city and town received central government subsidies to construct bus terminals, which became much busier interchanges than the railway stations. Medium-distance buses faced competition from light commercial vans known as Colts, which provided faster—though not safer—transport for passengers with little accompanying baggage. Transport between the village and market town had shifted in the 1950s to buses, which over short distances were supplemented by bicycles and pony-carts. In the late 1970s buses began to lose business to light commercial vehicles or small pick-ups. These ran more frequently than the buses and could more easily detour off the main roads. If need be they could also be hired to carry a load of goods.

INTERPRETATION AND REPRESENTATION

The Large-Scale Sector: Dualism

In the late colonial period of the 1920s various glossy official and commemorative publications hailed the railways as a triumph of modern technology and organisation and, without needing to be explicit, as an important part of the justification for efficient colonial rule (notably Reitsma 1925, 1928; KRN 1930). By the 1960s, from a functional perspective, they were an engineering and organisational disaster. Within less than a century, railways had degenerated from a leading edge of modern capitalism to an arm of a bloated, dysfunctional and hopelessly corrupt state.

This history of Java’s railways may be encapsulated as a cycle of intrusion, adaptation and absorption. In the first decades, railways were an alien modern technology and organisational form, part of an emerging capitalist mode of production controlled by western enterprise. Railways were a vital part of what Burger (1939) described so perceptively as ‘the unlocking of Java’s interior for world commerce’. In Java’s emerging plantation economy, the productive potential of the new industrial revolution technology could be realised only with a transport system of equivalent scale to link the agro-industrial factory with world markets. The huge investment in railways and tramways was essential in restructuring the sugar industry after the crisis of the 1880s and 1890s, when real cane sugar prices collapsed in response to competition from the expanding European beet sugar industry. The Resident of Surakarta reported in 1891 that without the railways the sugar mills would not have survived the crisis. Smaller mills closed down and output was concentrated in larger and more modern factories. The subsequent growth in output simply could not have been accommodated by traditional carts and river prahu at a price that would have been competitive on world markets. Devastated by blight, in the 1890s the coffee industry was also enabled to restructure by the opening of rail access to the virgin slopes of Java’s highlands and southern hills (Schaik 1986).

What could not have been predicted before 1942 was the ultimate absorption of the railways into Indonesian society. This happened in two associated ways, first the economic eclipse of railways by road transport and, secondly, their political eclipse by nationalisation and rampant bureaucratisation. The economic competition which railways encountered from motor and pedal transport from the 1920s was a worldwide phenomenon that flowed from a fundamental disparity in scale and unit cost. Rail could maintain dominance over pedestrian and animal-powered transport but without regulatory protection had to compete head-on and at a disadvantage with motor transport. Ultimately fares were driven below long-run marginal cost and railways became a non-profit public good.

To withstand intensifying road-based competition, railways needed both state protection and very efficient internal organisation. Instead they became organisationally dysfunctional. The main network of the State Railways (Staatsspoor) was in 1950 reconstituted as the Railway Department (Djawatan Kereta Api), which in turn took over management of the residual private railway and tramway systems as part of a single nationalised system. Schedules, customs and rituals were faithfully maintained but profitability ceased to matter. The government funded growing financial deficits but did not undertake the massive investment needed to modernise the system, which gradually contracted from its 1931 peak of 5,500 kilometres. Foreign aid funded replacement of rolling stock on main lines, but elsewhere vintage technology survived as though in a quaint open-air museum. By the 1960s the Railways Department had become a vast employment relief organisation.

Dualism has been one way of representing this historical experience. Boeke’s original concept of social dualism came to attention only in the 1950s, at the end of his career and amidst the tense period of decolonisation. Its acceptance or rejection differentiated ‘neo-colonial’ from ‘anti-colonial’ writers. In an incisive critique first published in 1957, the young Indonesian economist Sadli (1971) pointed out the lack of any logical chain of reasoning in Boeke’s argument and perceptively distinguished three possible causes of dualism:

• the import of an (alien) capitalist society;

• the ‘high capitalistic structure’ of that imported society;

• the inability or unwillingness to adapt of the pre-capitalist host society.

does not fit a crude dualistic model. The most generous interpretation is that dualism may have been a late-colonial phase. From the outset railways were involved in a process of dynamic interaction with the small-scale transport sector, and the alliance between colonial capital and the colonial state became increasingly defensive.5 By the 1930s small-scale road

transport was eroding the market share of railways. After independence, Indonesianisation of the state railways and nationalisation of private railways eliminated their capitalist features. Under state ownership and control railways remained a large-scale, capital-intensive enterprise and thus part of the ‘formal’ sector. However, instead of operating under commercial norms, they were now managed to achieve political, bureaucratic and social objectives. In Sadli’s terms, the ‘imported’ and ‘capitalistic’ features of railways atrophied when they were absorbed into the national economy and society.

The Small-Scale Sector: Static or Dynamic?

Railways stimulated rapid expansion in the area and output of the large-scale plantation sector. The other fascinating side of the story is the mixed response of the small-scale sector. The Residency reports of 1891 put forward a widespread view that railways stimulated trade but not village agriculture. In other words, by widening the market the railways created a ‘vent for surplus’, raising the proportion of household time directed towards the market economy but without much change in the technology, scale or intensity of production. Thus somewhat more rice and dry-season (palawija) crops were sold on the market, along with fruit, coconuts, coconut oil, palm sugar, chickens, eggs and some handicrafts, but these were adjustments on the margin, not a transformation.

This essentially passive or Boeke-like view of ‘peasant’ response sits awkwardly with the evidence cited above of the dynamic response of small-scale land transport to the intrusion of railways. Indigenous land transport had to surrender ‘line-haul’ traffic to railways but enjoyed increasing patronage in feeder traffic. This finding is consistent with recent evidence of a trend since the introduction of the Cultivation System in the 1830s of growth in off-farm employment opportunities and increasing circular labour migration (Boomgaard 1989; Elson 1994; Fernando 1996). Here there is strong evidence of economic transformation. The rapid development of motorised land transport in the early 20th century was

also not a new phenomenon but a more sophisticated phase that built on rising mass demand and increased supply of small-scale capital and entrepreneurship, both indigenous and Chinese.

The apparent lack of peasant response in the 1890s suggests an early formulation of the question that troubled Geertz in the 1960s. Geertz (1964, 1965), following on Dewey (1962), marvelled at the vitality and complexity of the local market (bazaar) economy and wondered at the lack of an organisational response. Why did such ‘rational’ economic actors remain in the familiar world of small, shifting coalitions and not take the ‘logical’ next step of forming business firms? In the 1960s it was possible to attribute failure of indigenous enterprise to economic pressure from western and Chinese business. Geertz also invoked the notion of a failed transition, by claiming to identify—the evidence is slender—a group of larger Muslim traders whose business had succumbed to the depression of the 1930s. If such people had not existed, they certainly ought to have existed. Yet in 1891 Resident after Resident had observed how little of large-scale trading was in indigenous hands. The 1891 reports give pause for reflection that perhaps village society and its superstructure of the bazaar economy was never actually a breeding ground for indigenous business firms, that in Geertz’s succinct phrase the Javanese were always ‘entrepreneurs without enterprises’.

Geertz (1963) saw one surface of this phenomenon, which he brilliantly but misleadingly labelled as ‘shared poverty’. The Javanese were their own worst enemy. As a society they needed, in their own self-interest, to be more individualistic, more selfish. ‘Shared poverty’ thus neatly linked observed economic behaviour with a sophisticated social construct of ‘other’, that perversely idealised Javanese villagers and empathised with their tragic plight, an enervating combination of bad luck and excessive virtue. Geertz reflected prevailing ‘developmentalist’ hostility to social mechanisms of redistribution but gave such behaviour uniquely Javanist and historical respectability. Though staunchly anti-colonial, he thereby gave a new lease of life to colonial representations of Javanese as submissive and virtuous ‘other’. Only in the 1990s have authors such Pemberton (1994), Ricklefs (1993) and Reid (1988, 1993) begun to challenge and deconstruct these colonial representations.

If social representations of ‘Javanese’ can now be challenged, then it is timely also to challenge economic representations. Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that Javanese traders and villagers were not socially crippled economic actors but skilled and sophisticated traders who performed efficiently in the market superstructure, pejoratively labelled the bazaar economy. This certainly fits the facts as they have been represented in the literature. Dewey (1962) and Alexander (1987) confirm Geertz’s assessment of the vitality of local markets. Citing contemporary accounts, Reid (1993) extends a long historical gaze to the role of Javanese traders in international trade in the 16th and 17th centuries. Hasselman

‘There reigns such a throng, noise and bustle that is to be expected only of a busy, trading nation.’ Such evidence could be greatly multiplied and is remarkable in its consistency over many centuries. It also accords with broader social observation that Javanese of any social rank are highly materialistic and, women especially, anything but naïve in money matters.6 Rather than ignore or discount the weight of evidence to accord

with casual theorising, perhaps we need a better explanatory theory. One line of inquiry is that Java may be another example of what Elvin (1973) in China provocatively labelled the ‘high-level equilibrium trap’. As a young scholar of China, Mark Elvin had been similarly puzzled at the paradox that a people who displayed such obvious entrepreneurial talent and had in the past achieved economic greatness should now be so easily disparaged as economically backward. Disregarding neo-colonial orthodoxy, Elvin argued that by the 19th century China had been

for several centuries a sophisticated and highly monetised market economy with complex institutions and a vast household sector, including agriculture, that had expanded to the limit of population within the constraints of pre-modern agricultural technology. Except in foreign trade and a few niches, there were no longer monopoly profits to be made within the framework of existing institutions. China is not of course directly comparable with Java. Until the early 20th century Java still had

unsettled agricultural land and was open to international trade and foreign investment (Booth 1988, 1998). The insight is that, in a narrowly based commercial economy, markets and institutions might become too efficient, in effect become saturated, and thus eliminate the scope for large-scale investment and capital accumulation. This is the institutional equivalent of the profitless ‘stationary state’ that haunted classical economists.

‘backwardness’ of Java, and especially Central Java, as shared poverty, cultural decadence and colonial exploitation? This is not to discount an oppressive influence from the Javanese courts, or to deny policy biases, but it does restore agency to the Javanese people.

Dualism and Globalisation

Boeke’s definition of social dualism as ‘the clashing of an imported social system with an indigenous social system of another style’ had no theoretical underpinnings. It was based upon observation, mediated by a set of beliefs which may be described as colonial ideology. The concept found no favour because those colonial beliefs were rejected along with the historical experience. Nevertheless, it does not follow that Boeke was entirely wrong. He may have lacked insight into the political economy of colonial exploitation, oversimplified industry structures and misread the dynamics of long-term economic development, but he does at least seem to have grasped the social tensions generated by economic transformation. If the word ‘imported’ is replaced by the word ‘globalised’, and if the formulation is shorn of its colonial connotations, this insight retains some relevance.

For the sake of argument and in hindsight the colonial economic experience between the mid 19th and mid 20th centuries can be reread as

a prior wave of globalisation involving land-extensive, agro-industrial production for export markets. Beginning on Java with introduction of the state-directed Cultivation System in 1830, the process intensified after the mid 19th century through application of modern, large-scale, capital-intensive industrial revolution technology. Java was the first part of Southeast Asia in which this technology was systematically applied, in particular to the sugar industry (Dick 1992). However, to maintain international competitiveness it was not sufficient to increase scale and reduce unit production costs. The scale and unit cost of transport and communications had also to be adjusted more or less in step. The Dutch achievement of the late 19th century was to visualise Java as a single

Indonesians fought for independence against the colonial economic and political system and, having gained sovereignty, worked towards its demise. The large-scale, modern sector including railways was nationalised and brought under state control—by 1958 all Dutch enterprises and in 1964/65 all other foreign enterprise. Except for production-sharing agreements in the oil industry, foreign investment and capitalism had been eliminated by the end of the Sukarnoist period of Guided Democracy (1959–66). Alongside the large but highly inefficient state sector was an atomised sector of household and small-scale enterprises. Despite some surviving export capability, neither sector was well articulated with the global economy. As exemplified by the country’s chronic balance of payments crisis, Guided Democracy/Economy had been the culmination of a period of disengagement from the international economy.

The New Order ushered in a new wave of globalisation. Beginning with the new foreign investment law of 1967, private capital and technology again flowed into Indonesia, this time without the vehicle of colonialism and with an increasing share directed to manufacturing rather than agriculture. This process accelerated after the mid 1980s with the non-oil export drive and the liberalisation of trade and investment. The experience has been well documented by Hill (1996) and others, and only two aspects need to be drawn out here.

Secondly, the new pattern of globalised enclaves has redrawn the political faultlines. The export-oriented, industrialised, high-rise urban economy has become the post-colonial, post-plantation formal sector. Beyond Jakarta and Surabaya there is resentment at the accretion of wealth and pursuit of conspicuous consumption in those enclaves. Even within Greater Jakarta, the displacement of huge numbers of people to make way for high-rise buildings, industrial estates, new towns and golf courses has generated popular anger. These alignments and tensions have as ever exposed the Chinese business community. On the margin of indigenous society, the Chinese have always been the indispensable conductor of economic electricity between the global economy and the indigenous economy and society. Their economic supremacy and visible wealth make the Chinese community the obvious target of antagonism towards ‘alien’ economic forces. In May 1998 provocateurs exploited this vulnerability with terrifying results.

In 1997–98, collapse of the rupiah, banking crisis, revolution and total loss of confidence destroyed the controlled-temperature hot-house in which the globalised sector had thrived and delivered the benefits of employment and income growth. In a more open and volatile political system, it has become an unresolved question as to whether Indonesians are willing to bear the cost of rehabilitating the formal, corporate, globalised sector. Significant interests go the other way. Despite the massive loss of jobs in the manufacturing, construction and financial sectors, devaluation has boosted export incomes for agricultural producers and some manufacturers, while the relaxation of urban by-laws and the lure of cheaper goods and services have increased job opportunities in the informal sector. As in the 1950s and 1960s, Indonesians may deliberately or by default make a political choice on equity grounds to muddle along with a less globalised and less sophisticated economy.

CONCLUSION

in poverty, in Indonesia as elsewhere in Asia. Many Indonesians, however, like citizens even of OECD countries, are disconcerted by the pace and nature of social change. Despite the empirical evidence of sharply declining incidence of poverty, material progress and rising levels of education have not been perceived as improving popular welfare, not least because of increased vulnerability and reduced social protection. Among youth there is also the problem of unfulfilled aspirations. In the colonial period hostility against the capitalist sector was easily transferred into anger at colonial rule. In the late 1990s it was directed against the New Order regime.

Perhaps economists have paid too little heed to the stubborn insistence in Indonesian society on social unity, harmony and justice. One aspect is a belief that economic activity, and especially large concentrations of capital and wealth, should be seen to be regulated by social and political norms. Market forces in the abstract, and by extension the agents of those market forces, can easily be portrayed as a threat to the integrity of society. Such beliefs were embodied in the 1945 Constitution, and in the Sukarno era were expressed in terms of socialist or communist ideology. Market forces were to be ‘guided’ by the state on behalf of the people. The New Order destroyed the Communist Party and abandoned socialist rhetoric, but it did not eliminate deep-seated hostility towards market forces and concentrations of private capital (konglomerat). From an economist’s point of view most of this is ignorant nonsense to be dismissed out of hand. Nevertheless, in a democratic system widely held prejudices tend to be assimilated by the main political parties and to become an influence on policy. If social norms are violated, the outcome may be instability.

NOTES

* Earlier versions of this paper were presented in August 1998 at the IAHA (International Association of Historians of Asia) Conference in Jakarta and in November 1998 at CASA, Amsterdam. I am grateful for the comments of seminar participants, David Henley, Kai Kaiser, Merle Ricklefs and two referees.

1 ‘Dualism’ has been identified in various ways. The colonial economist Jan Boeke introduced the concept to the English-language literature as ‘the clashing of an imported social system with an indigenous social system of another style’(Boeke 1953). Objecting to cultural stereotyping, Higgins (1955) introduced the more economically specific concept of technological dualism, which with hindsight he would prefer to have defined as bi-modal production (Higgins 1992: 50). Geertz (1964) as an anthropologist preferred the distinction between ‘firm-centered’ and ‘bazaar-centered’ economy. In the mid 1970s a group of economists associated with the ILO brought the idea into mainstream development studies with the now familiar terms ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ sector. Myint (1970) is a good critical view.

2 Material for this section is taken from a set of surveys of local conditions, including the adequacy of transport, compiled by Residents in 1891 under an instruction of November 1890 and published as appendix C of the 1892 Colonial Report (Koloniaal Verslag). Twenty years after the opening of the first rail lines was long enough to perceive long-term trends in some Residencies; in others it was still possible to glimpse the immediate impact of new lines, while in some there were as yet no railways at all. (A Residency was an area composed of several regencies or districts, later known as kabupaten; in the late 1920s groups of Residencies were combined to become the new provinces.) 3 A good comparison would be the role of indigenous trading prahu as common

and even insured carriers during the 1930s (Dick 1975, 1987).

4 This paragraph draws on material from the archive of the OJS (Oost Java Stoomtram Mij [East Java Steamtram Co.]) in the Royal National Archive (ARA).

5 Dick (1980) drew the same conclusion in the case of the interisland shipping industry.

6 A point that has been well argued by Henley (1997).

REFERENCES

Alexander, J. (1987), Trade, Traders and Trading in Rural Java, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Boomgaard, P. (1989), Children of the Colonial State: Population Growth and Economic Development in Java, 1795–1880, CASA Monograph no. 1, Free University Press, Amsterdam.

Booth, A. (1988), Agricultural Development in Indonesia, Allen and Unwin, Sydney. —— (1998), The Indonesian Economy in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A

History of Missed Opportunities, Macmillan, London.

BPS (1996), Population of Indonesia: Results of the 1995 Intercensal Population Survey, Series S2, Jakarta.

—— (1997), IndonesianStatistical Yearbook 1996, Jakarta.

Burger, D.H. (1939), De Ontsluiting van Java’s Binnenland voor het Wereldverkeer [The Opening of Java’s Interior to World Commerce], Veenman, Wageningen. Dewey, A. (1962), Peasant Marketing in Java, Free Press of Glencoe, Chicago IL. Dick, H.W. (1975), ‘Prahu Shipping in Eastern Indonesia: Part I’, Bulletin of Indonesian

Economic Studies 11 (2): 69–107.

—— (1980), ‘The Rise and Fall of Economic Dualism: The Indonesian Inter-Island Shipping Industry’, in R. Garnaut and P. McCawley (eds), Dualism, Growth and Poverty, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU, Canberra.

—— (1987), ‘Prahu Shipping in Eastern Indonesia in the Interwar Period’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 23 (1): 104–21.

—— (1992), ‘Nineteenth-Century Industrialization: A Missed Opportunity?’, in J. Th. Lindblad (ed.), New Challenges in the Modern Economic History of Indonesia, Programme of Indonesian Studies, Leiden; 123–48.

Dick, H., and D. Forbes (1992), ‘Transport and Communications: A Quiet Revolution’, in A. Booth (ed.), The Oil Boom and After: Indonesian Economic Policy and Performance in the Soeharto Era, Oxford University Press, Kuala Lumpur: 258–79.

Elson, R.E. (1994), Village Java under the Cultivation System, 1830–1970, Allen and Unwin, Sydney.

Elvin, M. (1973), The Pattern of the Chinese Past, Eyre Methuen, London.

Fernando, M.R. (1996), ‘Growth of Non-Agricultural Activities in Java in the Middle Decades of the Nineteenth Century’, Modern Asian Studies 30 (1): 77–119. Geertz, C. (1963), Agricultural Involution, University of California Press, Berkeley

CA.

—— (1964), Peddlers and Princes, University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL. —— (1965), The Social History of an Indonesian Town, MIT Press, Boston MA. Hasselman, B.R.P. (1862), Mijne Ervaring als Fabrikant in de Binnenlanden van Java

[My Experience as a Factory Owner in the Interior of Java], M. Nijhoff, The Hague.

Henley, D. (1997), Entrepreneurship, Individualism and Trust in Indonesia, Paper presented at a Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam/University of Indonesia Seminar, 'New Directions in Indonesian Social History', Jakarta, 9 December. Higgins, B. (1955), ‘The Dualistic Theory of Underdeveloped Areas, Ekonomi dan

Keuangan Indonesia (February): 58–78.

—— (1992), All the Difference: A Development Economist’s Quest, McGill–Queen’s, Montreal.

Hugo, G. (1996), ‘Urbanization in Indonesia: City and Countryside Linked’, in J. Gugler (ed.), The Urban Transformation of the Developing World, Oxford University Press, Oxford: 133–83.

Ingleson, J. (1986), In Search of Justice: Workers and Unions in Colonial Java, 1908– 1926, Oxford University Press, Singapore.

Knaap, G. (1989), Transport, 1819–1940, Changing Economy in Indonesia, v. 9, Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam.

KRN (De Koloniale Roeping van Nederland [Holland’s Colonial Call]) (1930), Nederlandsch–Engelsche Uitgeversmaatschappij, The Hague.

KV (Koloniaal Verslag) (1892), Landsdrukkerij, The Hague.

Myint, H. (1970), ‘Dualism and the Internal Integration of the Underdeveloped Economies’, Banca Nazionale del Lavoro 23: 128–56.

OMW(Onderzoek naar de Mindere Welvaart der Inlandsche Bevolking op Java en Madoera

[Inquiry into the Diminishing Welfare of the Native Population of Java and Madura]) (1907), v. IVa, Kolff, Batavia.

Osten, W.J. (1930), ‘De Suikerafvoer naar Soerabaia’ [The Sugar Transport to Surabaya], Spoor- en Tramwegen [Rail- and Tramways] I: 378; and II: 8–10, 41–2.

Pemberton, J. (1994), On the Subject of Java, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY. Reid, A.J.S. (1988), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce: The Lands Below the Winds,

Yale University Press, New Haven CT.

Reid, A.J.S. (1993), Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce: Expansion and Crisis, Yale University Press, New Haven CT.

Reitsma, S.A. (ed.) (1925), Gedenkboek der Staatsspoor- en Tramwegen in Nederlandsch-Indie 1875-1925 [Commemorative History of the State Railways and Tramways in the Netherlands Indies], Topografische Inrichting, Weltevreden.

—— (1928), Korte Geschiedenis der Nederlandsch-Indische Spoor- en Tramwegen [Short History of the Netherlands Indies Railways and Tramways], Kolff, Batavia. Ricklefs, M.C. (1993), War, Culture and Economy in Java, Allen and Unwin, Sydney. Robinson, Tjalie (1952), Piekerans van een Straatslijper [The Cutler’s Apprentice],

Masa Baru, Bandung.

Sadli, M. (1971), ‘Reflections on Boeke’s Theory of Dualistic Economics’, in B. Glassburner (ed.), The Economy of Indonesia, Cornell University Press, Ithaca: 99–123 (originally published in Ekonomi dan Keuangan Indonesia, June 1957). Schaik, A. van (1986), Colonial Control and Peasant Resources in Java, Netherlands