Reducing agricultural

expansion into forests

in Central

Kalimantan-Indonesia:

Analysis of implementation

and financing gaps

Rizaldi Boer, Dodik Ridho Nurrochmat,

M. Ardiansyah, Hariyadi, Handian

Purwawangsa, and Gito Ginting

Center for Climate Risk &

Opportunity Management

Bogor Agricultural University

2012

PROJECT

REPO

Acknowledgment

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. Indonesia: Context

Palm oil is one of the most important agricultural commodities in Indonesia, and plays a significant role

in the country’s economic development, representing 2.8% of the country’s GDP (14.5 billion USD in

2008). Various studies have shown that the net present value (NPV) of one hectare of palm oil could be as much as US$3,400 over a 25 year period1. The palm oil industry employs as many as 6 million people2. As such, it is no surprise that Indonesia has set a target to increase its palm oil production from 25 million tonnes in 2012 to 40 million tons by 2020.

Between 2005 and 2010, 26% of deforestation in Indonesia could be attributed to the expansion of palm oil3. Therefore palm oil has been associated with the loss of biodiverse tropical rainforests and

Indonesia’s high rate of deforestation.. Other causes include logging for timber, pulp and paper, subsistence agriculture, mining, and commercial agriculture.

The average annual growth rate of palm oil plantations has grown rapidly, going from 14,000 hectares per year (1967-1980) to 365,000 hectares per year (1991-2010)4. According to the FAO-OECD, global consumption is expected to increase over 30% in the next decade5. Based on current production trends, an additional 12 million hectares of oil palm plantings may be required to meet global demand by 20506. It is worth noting that that palm oil is the most efficient crop in terms of productivity (i.e. oil yield per hectare of land occupied by the crop). The average yield of palm oil in Indonesia and Malaysia is respectively 9.3, 7.6 and 5.8 times higher than the averages for soybean oil, rapeseed oil and sunflower oil7.

In 2009, the President of the Republic of Indonesia announced a voluntary emissions reduction target of 26% by 2020, and 41% if it received international assistance. In 2010, Indonesia and Norway signed a Letter of Intent to reduce deforestation.

Since land use change is responsible for 83% of Indonesia’s emissions, reducing forest and peatland

2. Central Kalimantan

Central Kalimantan was selected as the REDD+ pilot province under the Indonesia-Norway Letter of Intent. There is therefore political momentum to redirect Central Kalimantan’s development path towards low carbon development and a policy process is underway. However, there are also strong economic interests to develop coal mining and large-scale agriculture in ways that are not necessarily compatible with this low carbon development model.

With available land for agricultural expansion growing scarcer and scarcer in the islands of Java and Sumatra, palm oil expansion is increasingly taking place in Central Kalimantan and West Papua. The Government of Central Kalimantan has established a target to increase its area of palm oil plantations from 1 million hectares to 3.6 million hectares by 2020.

44% of Central Kalimantan’s population relies directly on palm oil for their livelihoods. Most of the palm oil production in Central Kalimantan is dominated by plantation companies (89%). Only 11% of the area under palm oil production is cultivated by smallholders.

3. Analysis

The Centre for Climate Risk and Opportunity Management in Southeast Asia Pacific (CCROM - SEAP), a research centre at Bogor Agricultural University, in collaboration with the World Resources Institute (WRI), assessed the potential to reconcile growth of the palm oil sector and reducing deforestation through (i) the expansion of palm oil plantations on low-carbon land, and (i) increasing productivity.

The study focused on economic analysis to identify investments required to redirect increases of production. It also identified measures that would need to be implemented simultaneously to enhance protection of existing forests to prevent perverse incentives increased productivity could create perverse incentives to deforest new areas.

(i) Expansion on degraded land

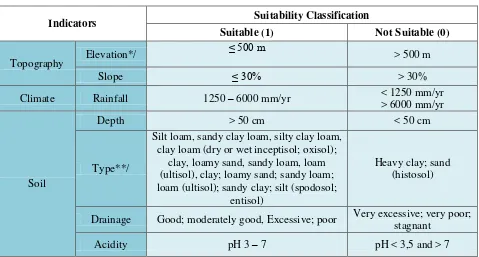

Degraded land suitable for palm oil expansion was identified through using a number of criteria including land cover, topography, rainfall, and soil type. It was assumed that 70% of suitable degraded land would be allocated to palm oil, reflecting the current proportion of palm oil to other commodities and crops.

(ii) Productivity increases

The report differentiates between four producers types: (i) independent smallholders; (ii) ‘plasma’

farmers, i.e. farmers linked to the Indonesian petani plasma system of partner companies; (iii) ordinary companies; and (iv) RSPO-certified companies.

The assumptions in the analysis were that independent smallholders’ production of fresh fruit bunches

4. Key findings, risks and policy recommendations

The report demonstrates that from existing plantation which currently stands at 1 million hectares, Central Kalimantan province could double oil palm production by 2020 from the current level as most of their existing plantations are still at very young age. However, the province has set up a target to increase the plantation area up to 3.5 million ha. With this target, it was estimated that the palm oil production by 2020 will be over three times of the current production. With this plan, about 1 million ha of forested land will be deforested. The study argues that Central Kalimantan could revise its current target of 3.5

million hectares’ oil palm to 2.9 million ha to avoid the deforestation without significantly reduce the production level.

In order to save the 1 million hectare of the “forested land”, two principal mechanisms: that should be done (i) the undertaking of a ‘land swap’ between ‘forested’ and ‘non-forested’ areas, coupled with a broader spatial planning exercise, and (ii) improvement of smallholder yields

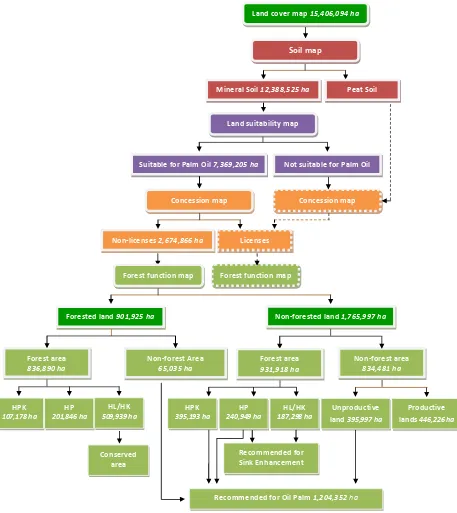

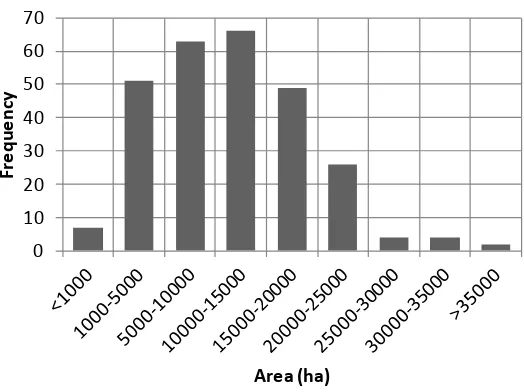

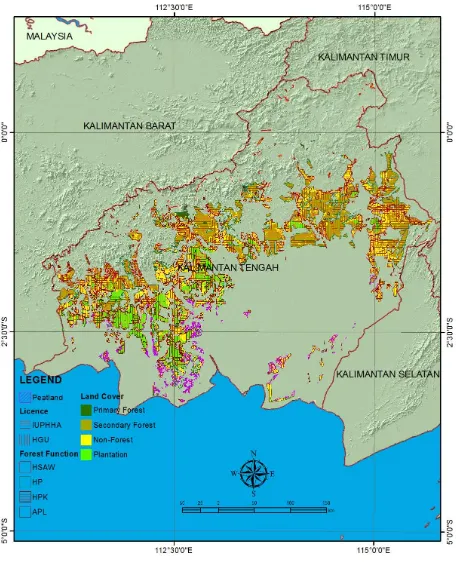

(i) Land swap policy

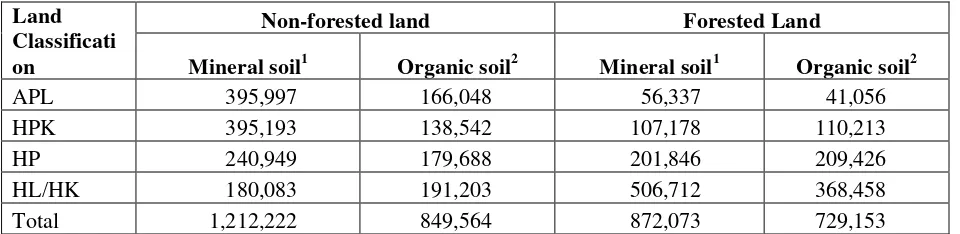

Government of Central Kalimantan Province have allocated land for palm oil plantations by about 3.21 million hectare for 272 companies of the 3.5 million hectare target. Of the 3.21 million ha, areas granted with HGU were about 39%, while the remaining is still in process of getting HGU8. Of 3.21 million hectares, only about 25% that have been planted with palm oil, while the remaining is still covered by forest (28% mostly secondary forest), shrubs/grassland (29%), agriculture (9%) and others (mining, rice field, ponds, transmigration area etc). About 11% of the areas are located in peatland. In addition, about 656,000 ha of the unplanted land are not suitable for palm oil (Figure 1)9.

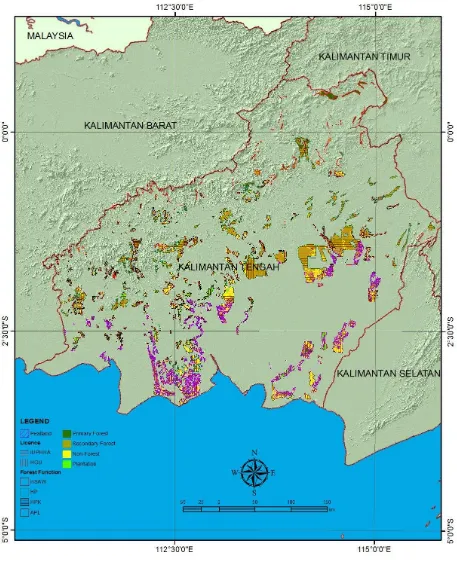

Areas which have not been granted with permits (unlicensed lands) and suitable for palm oil located in convertible production forest and APL10 are about 963,000 hectares. About 18% of these lands are still covered by forest, i.e. 11% in convertible production forests (HPK) and 7% in APL. On the other hand, about 240,000 ha of lands in production forest area is not covered by forest anymore, while by regulation this land cannot be used for non-forest based activities such as palm oil plantation.

To avoid the conversion of forested land in HPK and APL, Ministry of forestry needs to change the status of forest functions under a land swap mechanism. Total area for land swap is about 315,000 ha, i.e. non-forested land of production forest (HP) to convertible production forest (HPK) about 240,000 ha and forested land of convertible production forest (HPK) to production forest about 75,000 ha (Figure 1). The cost of this for 315 000 hectares would go up to 9.8 million USD. Procedures of changing such Forest Area classifications can be found in Government Regulation No. 10 of 2010 and Ministry of Forestry Regulation No. 34 of 2010. This process must also be closely coordinated by the on-going process of the

provincial and district government’s spatial plan revision.

8 About 21% in the form of izin lokasi (location permit) and 40% are still in the early stage of process or no information.

9

Suitability indicators used in the study followed WRI and Sekala’s proposed indicators with slight modification. 10

The public cost of swapping land (exchanging forest function) is estimated at IDR 3.4 billion or USD 375 000 per 12 000 hectares11. The unofficial cost may even be higher and this seems to be the main barrier to pursue this policy. It is believed that much of this cost could be lowered if strong political leadership supports these measures.

Figure 1. Distributions of licensed lands which are suitable (left) and not suitable (right) for palm oil. Note: HGU in the map refers to lands allocated for palm oil (Based on forest function of the MoF under Minister Forestry Decree Number S.292/ Menhut-II/2011. Non-suitable lands for palm oil plantation are areas highlighted with yellow in APL (horizontal lines), and yellow and light blue in HPK (vertical lines) and HP (oblique lines).

According to Head of Economic Division of Development Planning Agency of Central Kalimantan Province, as more than 3 million hectare of lands already allocated for big plantation, the release of HPK for APL will not be intended for big companies anymore, but it would be allocated for small holder farmers.

Changing the status of forested land in HPK with forested land in HP faces challenge. Many of non-forested land in forest area are occupied or used by communities. Giving these lands to other parties such as company always create the social conflict. Some companies left their lands unplanted due to high social cost. Current policy of Provincial Government for limiting the issuance of new land use right to big companies is very appropriate. Coupling this policy with the new Minister of Agriculture Regulation on Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil or ISPO (No. 19/Permentan/OT.140/3/2011) will be perfectly

11

matched12. ISPO obliges all oil palm companies including the existing ones to establish plasma plantation with size of at least 30% of their concession areas. Total of palm oil plantation in Central Kalimantan already reached 1.5 million ha and most of the companies have not met their obligation in establishing plasma plantation. Thus targeting the communities who used the non-forested lands in HP that will be changed to HPK for plasma plantation will create good synergy between these two policies.

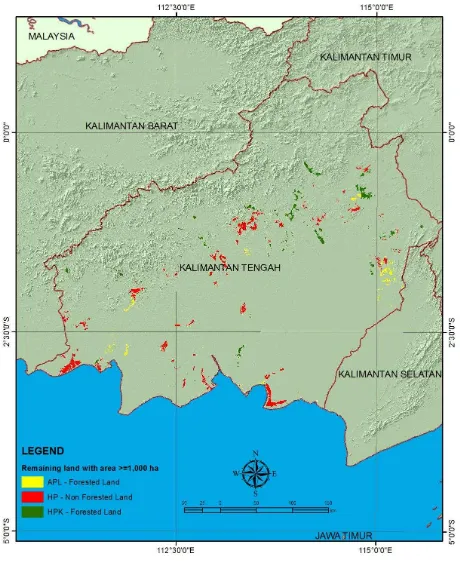

Figure 2. Distribution of unlicensed forested and non forested land in APL, HP and HPK

(ii) Yield improvements

Yield improvements can contribute to reduction of the land demand by about 232,000 hectares. With this program, some of the forested lands that have been allocated for palm oil could be saved. There are still about 544,000 ha of the licensed lands covered by forest. Following this findings, this study evaluate three land use scenarios as shown in Table 1, i.e. land swap, improved yield and save all forested lands of the licensed lands. To implement the last two scenarios, local governments need to revisit the land licensing process. Lands that have been allocated for palm oil plantations but still covered by forest and no HGUs are issued, may need to be suspended and cancelled. However, it should be noted that the most important barriers to companies expanding onto degraded land is the socio-legal risks involved. Land tenure needs to be addressed by the national and regional governments, with the support of transition

12

ISPO will be officially effective as of March 2012 and it is targeted that all oil palm plantation companies will

finance, in order for these to take place. Interim REDD+ finance and international development cooperation would be a key source of such finance, especially at the early stages of implementation.

Table 1. Land allocation scenarios for the establishment of palm oil plantation in Central Kalimantan

Lands for palm oil plantation

Baseline Land-swap Improved Yield Saved all forested

land

Sub-Total 1,017,073 1,606,154 776,124 1,847,103 544,049 1,847,103 0 1,847,103

Total 2,623,227 2,623,227 2,391,152 1,847,103

This study estimated that future production pattern of the CPO of the land swap and improved yield scenarios will be the same as that of the baseline scenarios. The production of the CPO will continue to increase until 2033 with peak production of about 12.5 million tons and start declining slowly. However for the save all forested land scenario, the CPO production will continue to increase up to 2030 with peak of production 11.2 million tons and the decline quite rapidly since more plantations have completed their life cycle. If the existing plantations of the plasma and independent farmers that will be replanted later are also targeted for the yield improvement program, the implementation of the saved all forested land scenario might not result in production which is significantly different from the other scenarios.

The future production pattern of the CPO of the land swap and improved yield scenarios will be the same as that of the baseline scenarios. The production of the CPO will continue to increase until 2033 with peak production of about 12.5 million tons and start declining slowly. However for the save all forested land scenario, the CPO production will continue to increase up to 2030 with peak of production 11.2 million tons and the decline quite rapidly (Figure 3.6) since more plantations have completed their life cycle. If the existing plantations of the plasma and independent farmers that will be replanted later are also targeted for the yield improvement program, the implementation of the saved all forested land scenario might not result in production which is significantly different from the other baseline scenario. Therefore, in the future oil palm production targets should be expressed in tonnes of oil produced rather than hectares occupied, and encourage efficiency over horizontal expansion.

The report shows that the upfront costs of investment to increase productivity would be amply paid back through an increase in value accruing over a 25-year cycle. Increases in productivity are achieved through investments in soil health, and uptake of better varieties. The independent smallholders bear the greatest opportunity to increase yields. To increase the benefit of an independent smallholder (5 ha) by IDR 59 million, one has to spend additional costs of IDR 39 million; for plasma farmers, spending additional costs of IDR 27 million will increase benefits to IDR 95 million.

holders for the future development of palm oil plantation, this study estimated there will be about 930,000 ha of lands allocated for small holders (70% plasma and 30% independent farmers). If this were also to be implemented, there will an additional cost of about IDR 5.6 trillion.

Implementation of improved yield scenario for small farmers and plasma farmers will have positive impact on environment as it will reduce the demand for lands from 2.62 to 2.39 million ha or about 232,000 ha and this could avoid the conversion of forested land at that size. In combination with land swap, forested land that can be saved will increase to 473,024 ha. This is equivalent to reduction of emission from deforestation of about 480 million ton of CO2. If government decides to save all forested

land allocated for palm oil as conservation area, there will be an additional of 544,049 ha forested land being saved, thus in total will be about 1,017,073 ha (see Table 1). And this is equivalent to reduction of emission of about 746 million ton CO2. With this reduction, the potential earnings received from carbon

credit for those saved forests could not cover the additional cost required for yield improvement program. However, the additional benefit from yield improvement will result in significant increase in income

5. Next steps

In the absence of premium prices for certified palm oil, and sufficient demand for carbon credits, transition public finance can be used to build a framework within which it is possible for private sector to invest in increasing sustainable palm oil supply. The proposed way forward will require strong political will from the central, provincial and district authorities to carry out the land swap policy. Aligning incentives for all will be tricky, if not impossible, and requires further analysis and open discussion.

Meanwhile, increases in productivity on land already under production will be economically viable in the long term for both companies and smallholders. However, public finance is needed to catalyze those investments, especially in the case of smallholders. Those programmes should include extension, access to better varieties, and increased access to credit.

It is crucial to ensure increases in productivity do not result in further encroachment into forests (enabled by additional capital and incentivized by additional profitability). Therefore, some of the REDD+ funds could be utilized to increase monitoring and enforcement capacity of forest frontier.

A number of ongoing private sector initiatives can be leveraged accelerate the piloting and large scale implementation of the solutions put forward by this paper. The Smallholder Acceleration and REDD+ Partnership (SHARP), initiated by Sime Darby, is a multi-stakeholder grouping that works with the private sector to support smallholders with the triple goal of improving rural livelihoods, increasing yields and reducing deforestation. The Partnership on Indonesian Sustainable Agriculture (PISAgro) is an alliance of companies collaborating to improve the productivity and quality of different commodities, with special attention to environmental sustainability and the expansion of opportunities for smallholder farmers. Sinar Mas is leading the palm oil PISAgro working group.

GLOSSARY

ABA

= Area Boundary Arrangement

AMDAL =

Analisis Mengenai Dampak Lingkungan

; environmental impact analysis. In this

study the definition of AMDAL is the same asEIA although theoretically both

terms could have different meanings.

BAPLAN

=

Badan Planologi Kehutanan

; Directorate General of Forest Planology

BAPPEDA =

Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Daerah

; Regional Development Planning

Agency

BCR

= Benefit Cost Ratio

BLHD

=

Badan Lingkungan Hidup Daerah

; Regional Environmental Agency

BPN

=

Badan Pertanahan Nasional

; National Land Agency

BPS

=

Badan Pusat Statistik

; Center for Statistics Agency

BULOG =

Badan Urusan Logistik

; a national agency responsible for controlling and

stabilizing logistics, especially staple foods.

CC

= (RSPO) certified company

CPO

= Crude Palm Oil

DISBUN

=

Dinas Perkebunan

; Regional Plantation Office

DISHUT

=

Dinas Kehutanan

; Regional Forestry Office

EBITDA

= Earnings Before Taxes, Depreciations, and Amortizations

EIA

= Environmental Impact Assessment

FFB

= Fresh fruit bunch

FS

= Feasibility study

HCVA

= High Conservation Value Area

HCVF

= High Conservation Value Forest

HGU =

Hak Guna Usaha

, Right of Business Utilization in an allocated land released by

the national land agency (BPN)

IRR

= Internal Rate of Return

IS

= Independent Smallholders

ISPO

= Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil

KEMHUT

=

Kementerian Kehutanan

; Ministry of Forestry

KEMTAN

=

Kementerian Pertanian

; Ministry of Agriculture

NPV

= Net Present Value

OC

= Ordinary oil-palm company

Perda

=

Peraturan Daerah

; Regional Regulation

Permenhut

=

Peraturan Menteri Kehutanan

; Forestry Minister Regulation

Permentan

=

Peraturan Menteri Pertanian

; Agricultural Minister Regulation

PF

= Plasma Farmers

PP

=

Peraturan Pemerintah;

Government Regulation

ROI

= Return on Investment

RSPO

= Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

RTRW

=

Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah;

Regional Spatial Planning.

SKPT =

Surat Keterangan Pemilikan Tanah;

letter of notification for land ownership

released by village head.

UMR

=

Upah Minimum Regional;

a minimum labour wage

Context Setting

Palm oil is one of the most important agricultural commodities in Indonesia, contributing significantly to

the country’s economic development. During the last decade, palm oil has been the most significant agricultural export. The value of export of palm oil related products in 2008 reached 14.5 billion USD

(Indonesian Palm Oil Commission, 2008; GAPKI, 2009). This is about 2.8% of 2008 Indonesia’s GDP.

Palm oil is not only a valuable source of foreign exchange but also revenue and employment. Various

studies revealed that the NPV of one hectare of oil palm could go up to 3,400 USD over a 25 year period

in the production centre regions such as Aceh, North Sumatra, Riau and West Kalimantan (Cason et al.,

2007; BisInfocus, 2006). Meanwhile, the employment generated from palm oil production might reach 6

million people (Goenadi, 2008). It is not surprising that the growth of palm oil plantation is the fastest

among other plantation commodities.

From 1967 to 2010, the area of palm oil plantation has grown very rapidly, particularly after 1990 (Figure

1). Between 1967 and 1980, the growth rate of palm oil establishment was only 14 thousand hectare per

year. Between 1981 and 1990, it increased to about 90 thousand hectare per year, and between 1991 and

2010 it went up to 365 thousand hectare per year (Ditjenbun, 2011). In addition to the rapidly growing

area, (the other more basic things is spread) [not clear], which was originally only in three provinces in

Sumatra alone (from 27 provinces), but has now spread across 19 provinces in Indonesia (from 33

provinces). Sumatra still has the largest area, which reached 74.87% followed by Kalimantan and

Sulawesi, respectively 21.35% and 2.40%. The composition of oil palm cultivation is also changing,

from previously only large plantations, but now includes smallholder and private estates. In 2010, the

total area of small holders was estimated to be around 3,315 thousand ha (42.4%), and large plantations,

4,510 thousand ha (57.6%). Sumatra dominated the three types of exploitation, while the Kalimantan and

Sulawesi, the site of the development of private plantations and smallholders (Ditjenbun, 2008). The total

production reached about 20 million ton (Figure 1.1). By 2012, it is targeted to reach production of about

25 million ton CPO.

Figure 1.1. Growth of palm oil area establishment and CPO production (Ditjenbun, 2011;

http://ditjenbun.deptan.go.id)

As the global demand for vegetable oils are expected to increase, this will encourage investment in the

palm oil industry leading to continued growth over the medium term. The global consumption is

expected to increase over 30% in the next decade (OECD-FAO, 2009) which will reach about 60 million

tons (FAPRI, 2010). Indonesia has targeted to double its production by 2020 which will reach 40 million

tons. Because of this, the Government put the oil industry of palm oil (CPO) in the four areas of industrial

revitalization program with the fertilizer industry, sugar, and cement. Funding this program was agreed

upon by the Minister of Finance. To meet this ambition, the Government of Indonesia planed to expand

the palm oil plantation to other islands. The industry will focus the expansion into Kalimantan and

Papua. In Kalimantan, the targeted provinces are Central Kalimantan, West Kalimantan and East

Kalimantan. Among the three provinces, Central Kalimantan has the highest target (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Realization and targeted area for palm oil plantation in Kalimantan

Provinces Realization (ha) Target Area (ha) Source

South Kalimantan 312,719 NA Ditjenbun (2011)

West Kalimantan 530.575 1,500,000 Statement of Vice Governor quoted by Suara Pembaharuan (2011)

East Kalimatan 662.565 1,000,000 Statement of Governor quoted by Viva Borneo (2012)

Central Kalimatan 1,054,168 3,595,173 Dinas Perkebunan (2011)

0

1967 1970 1973 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009

Oil palm expansion is a source of concern because it has occurred at the expense of Indonesia’s tropical

forest cover. Many studies indicate that oil palm expansion has also been held partly responsible for

wildfires and peatland degradation. All of these land use changes have resulted in carbon emissions.

Based on a study from Germet and Sauerborn (2008), the establishment of palm oil plantation on mineral

soil forested land would cause emission of about 650 ton CO2e per hectare, while if it was established on

forested peatland the rate of the emission would be much higher as a result of the decomposition of

drained peat. They stated that the conversion of one hectare of forest on peat releases over 1,300 ton

CO2e during the first 25-year cycle of oil palm growth and in the subsequent cycle would release about

800 ton CO2e per ha depending on the peat depth. Nevertheless, if the establishment of the palm oil

plantation takes place on grassland, the carbon fixation in plantation biomass and soil organic matter not

only neutralizes emissions caused by grassland conversion, but also results in the net removal of about

135 Mg carbon dioxide per hectare from the atmosphere (Germet and Sauerborn, 2008).

In the Second National Communication reported to the UNFCCC, it was reported that the contribution of

forest and grassland conversion, including peat fire, to total national GHG emissions from 2000 to 2005

was more than 50%. Therefore, the land use change and forestry sector was decided to be the main sector

assigned to meet the 26% voluntary emission reduction target announced by the President of the Republic

of Indonesia at the G-20 meeting in Pittsburgh and at COP15 in Copenhagen. Of 26%, LUCF and

peatland is expected to contribute to about 22%. As previously mention, the conversion of forest and

grassland was mainly for oil palm expansion. It was also indicated that oil palm expansion has partly

responsible for wildfires and peatland degradation. Therefore this sector has received many attentions

from national and also international communities to limit the expansion of palm oil to forested land.

In the light of the above concern, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales on November 18th 2009

convened a meeting of agribusinesses active in rainforest countries to discuss how the goal (of limiting

the expansion of palm oil into forested land) might be achieved. There was general agreement that it

would be possible to increase production, without further deforestation, by increasing yields,

rehabilitating degraded land and reducing waste along the supply chain. The meeting proposed two

strategies to meet the objective. The first proposal was to examine how smallholders might increase their

yields. In Indonesia, increasing yields from the current average of 3 tonnes per hectare to 5 tonnes per

hectare (well within technical limits) could spare the need to develop two million hectares of new land.

The second proposal was to expand the plantation on degraded and non-forested lands, which are

currently difficult for companies to access because of land titling issues. This study aimed to evaluate and

Economic Analysis for Changes

at Producer Level

A. Business case under BAU

This chapter discusses current and future situations of oil palm plantation business by taking examples of

four producers, i.e. independent farmer or “petani mandiri”, plasma farmer or “petani plasma”, ordinary

company, and RSPO certified company.13

A.1. Definitions& Assumptions

A.1.1. Definitions

Independent smallholder

Independent smallholder or “petani mandiri” means a farmer who managing, financing, and operating his

own farm by himself. Consequently, the productivity of farm is usually low due to lack of capital,

knowledge, and facilities.

Plasma farmer

Plasma farmer is a farmer who is supervised and supported by a partner company in managing, financing,

and operating his farm under the partnership scheme of “nucleus-plasma” or “pola plasma-inti”.Plasma farmer is also called as plasma-farmer or “petani plasma”.

Ordinary company

Ordinary company refers to an oil-palm estate company that is practicing good agricultural principles, but

is currently not certified under RSPO (Roundtable Sustainable Palm Oil) scheme.

13 Data were mainly taken from Central Kalimantan

Certified company

Certified company (RSPO certified) is an oil-palm estate company, where his estate operation has been

certified by third party, compliance with RSPO standards.

A.1.2. Characteristics of Farms and Assumptions

A.1.2.1. Characteristics of farm’s ownerships

Independent smallholder

1. No specific farm design and no plan for infrastructure development (roads, bridges, etc.)

2. Limited capital

3. Usually planting uncertified oil-palm seeds.

4. Not applying SOP (standard operational procedure) in farming practices.

5. Low fertilizer inputs

6. Insufficient pesticides applications

7. Low plant health (highly attacked by pests and insects)

8. Intensity of farm maintenance depends on the financial situation of farmer

9. Low productivity14 (2.60 – 11.90 tons/ha/year) specify whether tons of fresh fruit bunches or

crude palm oil

Plasma farmer

1. Farm development and maintenance during the first four years are managed by a partner company

(nucleus), so the quality of farm until fourth year is the same with farm of the partner company.

2. After fourth years, the management of farm is handed over to the plasma farmer.

3. Farm design follows the nucleus farm included the infrastructure development (roads, bridges,

etc.).

4. Planting certified oil-palm seeds.

5. Applying SOP (standard operational procedure) of the partner company (nucleus) until the fourth

year operation, however, after handing over the management of farm depends on the farmer.

6. Usually, farmer applies lower fertilizer inputs after handing over.

7. Insufficient pesticide applications after handing over.

8. Moderate plant health

9. Intensity of farm maintenance depends on the financial situation of farmer

14

10. Moderate plant productivity (4.06– 18.59 tons/ha/year)

Ordinary Company

1. Well designed farm and infrastructure development (roads, bridges, etc.).

2. Planting certified oil-palm seeds.

3. Applying SOP (standard operational procedure) of good agricultural practices

4. Applying appropriate fertilizers inputs and pesticides.

5. Controlled pest attacking

6. Not yet focus to manage HCVA (high conservation value area)

7. High productivity (6.35 – 29.05 tons/ha/year)

RSPO Certified Company

1. Well designed farm and infrastructure development (roads, bridges, etc.).

2. Planting certified oil-palm seeds.

3. Applying SOP (standard operational procedure) of good agricultural practices

4. Applying appropriate fertilizers inputs and pesticides.

5. Controlled pest attacking

6. HCVA (high conservation value area) has been managed properly

7. High productivity (6.35 – 29.05 tons/ha/year)

Is assumed that an ordinary company has implemented good agricultural practices, therefore, the only

difference between the ordinary company and the RSPO certified company is in their management of

HCV areas.

Table 2.1: Characteristics of Farms and Requirements for Improvements

Type of Farms Current technology Improvement Requirement for

improvement

Independent Smallholder

Seed uncertified seed Certified seed Extension service

Increase use of fertilizers and pesticides Fertilizer 200-300 kg/y 600-1000 kg/y

Pesticide 1-3 l/y 3-5 l/y

Labor 30-40 mandays/y 40-60 mandays/y

Yield 2.60-11.90 t/y 3.25-14.88 t/y

Plasma Farmer Seed certified seed Extension service

Increase use of fertilizers and pesticides Fertilizer 800-1200 kg/y 1000-1500 kg/y

Pesticide 3-5 l/y 5-6 l/y

Labor 50-60 mandays/y 60-80 mandays/y

Yield 4.06-18.59 t/y 5.08-23.04 t/y

Ordinary Company Seed certified seed Environmental management

Fertilizer 1200-1500 kg/y 1500-1800 kg/y

Pesticide 3-5 l/y 5-6 l/y

Yield 6.35-29.05 t/y 6.35-29.05 t/y (increased Fertilizer 1200-1500 kg/y 1500-1800 kg/y

Pesticide 3-5 l/y 5-6 l/y

Labor 50-60 mandays/y 60-80 mandays/y

Yield 6.35-29.05 t/y 6.35-29.05 t/y (increased average yield)

Organic fertilizer could be applied by an oil palm company, who is partly using waste (liquid & solid)

from CPO plant. For smallholders in Central Kalimantan full application of organic fertilizer at recent

situation is too costly. Some smallholders used “dung” of cattle as additional fertilizer only.

A.1.2.2. Assumptions

There are some assumptions applied in this study concerning to the calculation of costs and benefits of the

each type of plantation (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Assumptions applied in this study

Assumptions Independent

Smallholder

Plasma Farmer Ordinary company RSPO certified company

acquisition15 IDR 2,500,000/ha IDR 2,500,000/ha IDR 4,000,000/ha IDR 4,000,000/ha

15

f. Certification

b. Plant care Poor maintenance Moderate

maintenance

Responsibility NA NA Obligation

Obligation and

1,250,000/kg 1,300,000/kg 1,300,000/kg 1,300,000/kg

HCVA = High Conservation Value Area

SKPT = Letter of notification for land ownership released by village head HGU = Right of business utilization released by BPN (national Land Agency)

SHM = Land Ownership Certificate

Table 2-2 shows that generally independent smallholder needs investment cost only for land acquisition.

In Central Kalimantan, normally cost for land acquisition is about IDR 2.5 million per hectare, included

payment for land and letter of notification for land ownership released by the village head so called SKPT

(Surat Keterangan Pemilikan Tanah). For plasma farmers, there are two possibilities of land acquisition

permit they have, i.e. SKPT or HGU. The costs for HGU (Right of Business Utilization permit) and other

costs such as feasibility study and area boundary arrangement are usually paid by the partner company as

a part of loan package in a nucleus-plasma estate scheme. There is additional cost for company who wants

to apply RSPO certification, i.e. management of High Conservation Value (HCV) area. These costs are

usually spent at the initial stage of project.

Independent smallholders usually plant oil palm with low quality seeds, low inputs in terms of fertilizers,

pesticides, insecticide, and other important inputs. Plasma farmers are assumed planting a better quality of

seeds and other inputs rather than independent smallholders. Companies, both ordinary and RSPO

certified companies, are assumed to apply good quality of seeds, optimum inputs, as well as intensive

plant care and maintenance.

Independent smallholders are usually not spending investment for infrastructure. They use the existing

roads, bridges, and other infrastructures developed by government or company. For plasma farmers, roads

are usually provided by their partner company. Those investment costs for infrastructure are paid by

plasma farmers as a soft loan and spent in the initial stage of project. Besides those infrastructure costs for

roads and bridges, the oil-palm companies also spend additional investment costs for buildings. Cost for

buildings was spent in the initial stage of project, including offices and housing for management staffs

The other important costs in the operational stage are harvesting costs. Those costs are highly influenced

by production volume, technology and equipments, and prices of labour. The harvesting costs of

independent smallholders are low because they usually gain low production volume and apply less

effective technology and equipment. The oil-palm companies pay higher costs for harvesting than farmer

because their production volume is higher than of farmers, using better technology and equipments, as

well as paying labour costs.

Referring to the minimum regional labour price (UMR) of Central Kalimantan Province, the average

labour’s wage in an oil palm company is about IDR 37.800/day. For a company who wants to apply

RSPO certification, it needs additional cost for operating and maintaining RSPO and HCV standards.

Besides costs of production an oil-palm company shall also spend costs for community development as

state obligation or voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

It is assumed that the average production of FFB produced by usual independent smallholder is 8.06

ton/ha, improved independent smallholder 10.07 ton/ha, usual plasma farmer 12.59 ton/ha, improved

plasma farmer 15.74ton/ha and company 19.67 ton/ha. The normal price of FFB is assumed IDR

1,250,000 (farmer) to 1,300,000/ton (plasma and company), and in this study the premium price for

RSPO certified product is assumed 5% higher than normal price.16 It is also important to note that an

RSPO certified company usually allocates about 20% of the farm land for conservation purposes

(HCVA). Consequently, the production of oil palm will also decrease by ca. 20%.

By products of CPO plant, i.e. solid and liquid waste, are very valuable. Those wastes of CPO could be

applied for organic fertilizer (K-fertilizer). The total value of those by products is estimated to reduce

10% costs of fertilizer.17

A.2 Regular business operation of oil-palm estates

To operate business of oil-palm estate, there are some components of cost shall be considered, i.e.

planning and investment consist of feasibility study, permit, area boundary arrangement, and land

acquisition; plantation costs (planting and plant care); infrastructure costs (roads, bridges, building, and

housing); harvesting costs; wages and salaries, and corporate social responsibility (Table 2.3). The

16

According to the informal discussions during the RSPO annual meeting in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia November 2011, the maximum premium price for FFB is approximately only 4-5% above the normal price. MFH, Executive Director of GAPKI informed that the current price of the RSPO certified CPO is only about USD 0.5-1.0 above the normal price or higher less than 1% (personal communication).

17

following Table 2.3 is dealing only with regular business operation. The business operation of a certified

company is described in the Table 2.4.

Table 2.3. Costs for regular business operation of oil-palm estate

Components

e. Land acquisition 2,500,000 2,500,000 4,000,000

2. Plantation

a. Planting 13,695,500 34,343,000 34,344,000

b. Plant care (year 4-25) 98,053,950 96,998,757 170,457,900

3. Infrastructure

a. Roads - 12,204,000 12,204,000

b. Bridges - - 1,018,800

c. Buildings - - 694,000

d. Housing - - 870,000

e. Harvesting 14,099,120 22,029,875 61,467,285

f. Wages & salary - - 820,200

g. Corporate Social Responsibility - - 20,000

Total Costs (IDR/ha/25 year) 128,348,570 168,235,632 286,056,185

A.3 Business operation with productivity improvement &premium price for certified commodity

There are some additional costs to improve productivity of oil palm estate, particularly for plantation

costs, i.e. costs of planting and plant care. About 75% of costs for plant care are allocated for fertilizer’s

application and about 10% for pesticides18. After improved productivity, harvesting costs would be also

increase as a consequence of the raising production volume. For a plasma farmer or company which

wants to apply HCV standards or RSPO certification, additional costs for environmental impact

assessment and certification assessment are needed (Table 2.4).

18

Table 2.4. Costs for improvement business operation of oil-palm estate

e. Land acquisition 2,500,000 2,500,000 4,000,000

f. Certification assessment 40,000

2. Plantation

a. Planting 13,695,500 34,343,000 34,344,000

b. Plant care (year 4-25) 125,205,432 137,725,974 170,457,900

3. Infrastructure

a. Roads - 12,204,000 12,204,000

b. Bridges - - 1,018,800

c. Buildings - - 694,000

d. Housing - - 894,000

4. Harvesting 17,623,900 27,537,344 61,467,285

5. Wages & salary - - 25,425,138

6. CSR - - 20,000

Total Costs (IDR/ha/25 year) 159,024,832 214,470,318 310,725,123

According to key person interview and field observation, RSPO certification could not be applied for

independent smallholder farmer at current situation. Some constraints are faced among others are

reducing ca. 20% area of oil-palm plantation for HCVA19. The costs for preparation, maintenances, and

assessment for certification are the obstacles for independent smallholder farmers. The application of

RSPO certification for smallholders at recent situation is very difficult because it is too costly. Most of

farmers are smallholders, so it is almost impossible for them to exclude some of their farm land for

HCVA. It is also possible a smallholder will lose all of his lands if the lands laid on HCV criteria.

I. Economics of alternatives

In a situation of regular operation or business as usual (BAU), an independent smallholder with 5 hectares

of oil-palm plantation will have Earnings before Interests, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization

(EBITDA) of IDR 606,980,463 or gain Net Present Value (NPV) with discounted factor 15% per year (df

15%) of IDR 53,539,530 within 25-years of the completion oil-palm production cycle period. The

improvement of inputs, particularly better quality of seeds and proper fertilizer application are estimated

to increase the productivity of plantation of independent smallholder. Through application of better

inputs, an independent smallholder will get EBITDA of IDR765,779,981 and NPV (df 15%) of IDR

80,936,235 for their 5 hectare oil-palm plantation within the cycle period (Table 2.5).

Table 2.5 also points that a plasma farmer, who practicing regular operation (BAU) with 5 hectares

oil-palm plantation will receive EBITDA of IDR1,202,715,824 and NPV of IDR 64,910,357 within the

25-years production cycle. If a plasma farmer improved their agricultural practices, applied RSPO

certification, and gained premium price, then the total net benefit within the complete production cycle

will reach IDR 133,445,291.

It is estimated that an ordinary oil-palm company with total plantation area of 5,000 hectares will gain

NPV of IDR 132,427,796,086 within the 25-years of production cycle. By practicing management of

HCV area and applying RSPO certification without premium price, the NPV will decrease for IDR

87,382,225,976. If the price raises 5% (premium price) then the NPV will be of IDR 114,665,041,793. It

means lifting 5% price is not enough to compensate the reduction of production volume due to land

allocation for HCV area and costs for preparing and maintaining RSPO certification (Table 2.5).20

20

Table 2.5. Comparison of financial criteria for different types of oil-palm operations

- EBITDA (IDR) 1,240,611,049,844 1,380,584,423,867 1,377,494,423,867

- ROI (%) 96.17 108.14 106.27

- NPV (IDR) 87,382,225,976 114,665,041,793 109,557,341,245

- BCR 1.22 1.30 1.28

- IRR (%) 39.11 41.31 40.47

*) Certification for independent smallholder could not be applied, it is assumed that RSPO certified company has raised optimum

productivity, the additional earnings are come from premium price (5%)

**) Price of carbon assumed USD 5/mt CO2 equivalent

The costs for preparation, MRV, implementation, maintenance for carbon certification are much higher

than the assumed price of carbon. Assumed that the price of carbon is USD 5/ton CO2e, application of

carbon trading in an RSPO certified company will decrease the net benefit. By applying carbon trading

scheme, the company will gain NPV of IDR 109,557,341,245. It indicates that the NPV of carbon credit

application at price USD 5/ton CO2 is financially not benefiting oil-palm companies. Thus, to attract

carbon credit scheme in oil-palm sector the price of carbon has to be increased at reasonable level (will

Table 2.6. Increasing (decreasing) financial criteria for different types of oil-palm operations

Criteria

Increasing (decreasing) from BAU (GAP between BAU & improvements)*

Improved

*) This table discusses about GAP (increasing or decreasing) in percent, not discusses about the value of financial criteria.

Table 2.6 shows that the improvement agricultural practices will increase the NPV of independent

smallholder by 51%, BCR 6.98% and IRR 11.68. For plasma farmers, the improvement of agricultural

practices will increase the NPV of plasma farmers for about 105%, BCR 15.83%, and IRR 26.17%.

Application of HCV and RSPO standards without premium price will impact for decreasing NPV more

than 34%. Increasing price if 5% (premium price) for RSPO certified product will gain a higher NPV of

31% than normal price (price sensitive), but still much less than non RSPO certified company.

This study evaluated that at current situation, carbon credit scheme is not interesting to be applied in

oil-palm industry because of very low price of carbon (USD 5/mt CO2). Due to high transaction costs of

carbon project development (preparation, validation, registration, monitoring, verification, certification,

and leakage risk management), this study confirmed that the project will be feasible if the minimum

price of carbon is USD 7/tonCO2 equivalent, if the payment is given at the initial stage of project

(year-0), assuming that the carbon credit scheme is applied only in the HCV area – in this study ca. 1,000 ha or

20% of total plantation area of a company. If the payment of carbon scheme will be distributed evenly

along the plantation cycle (started from year-1 to year-25), then the minimum price of carbon is about

USD 27/ton CO2. However, if a full payment will be give at the end of plantation cycle (year-25) then the

price of carbon should be not less than USD 230/ton CO2.

J. Business Risks

Production

Generally, the production risk (lower productivity than expectation) will be higher in the use of

non-certified seeds and lower application of inputs. Therefore, the highest production risk is borne by the

independent smallholders. The plasma farmers have lower production risk than independent smallholders

management (maintenance) of plants. The production risk in a well managed oil-palm company is very

low.

Price of FFB

The risk of price fluctuation is usually high for independent smallholders and companies because until

now price is still an exogenous factor. For improved plasma farmer, the risk of price fluctuation is less

than independent smallholders because usually plasma farmers have signed a long-term contractual

agreement with a partner company. Instead of price, cost factors for improved plasma farmers are more

sensitive than price. It means, controlling the price of inputs through subsidies or market operation is

very important for improved plasma farmers and therefore, the input factors should be considered as

important point in a nucleus-plasma partnership scheme.

According to production volume, Indonesia is the market leader of CPO in the world. However, the

position of Indonesia in the world palm-oil market is not a price setter, but a price taker. Therefore, the

price factors are very fragile for the palm-oil industry, even for the RSPO certified company. Factually,

the position of RSPO certified company is not better than the others in influencing palm-oil prices

because of a narrow demand of certified products. It is also important to note that the world palm-oil

market is less influenced by supply-demand but is highly determined by derivative market. Thus,

Indonesia and other palm-oil producing countries are always positioned as price taker and consequently,

the risk of price fluctuation is unmanageable. This situation has to be improved by strengthening

bargaining power of palm-oil producers, among others by controlling production quotas and developing

more down stream palm-oil industries.

Availability of inputs

The risk for the availability of inputs is usually high for independent smallholders because they have no

direct access for certified (original) seeds nor high quality fertilizers and pesticides. For plasma farmer,

the risk for the availability of inputs is less than independent smallholders because usually plasma farmers

have had an agreement with their partner (nucleus) company. The risk for the availability of inputs of the

oil palm company is low because usually they have very good access and capital to buy the best inputs

(seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, etc.) and many companies even have own division of research and

development to produce high quality of seeds and apply “organic” fertilizers from liquid and solid waste

Unforeseen cost hikes

Generally, the risk of unforeseen cost hikes will be higher in the oil palm company rather than

independent smallholders and plasma farmers. The highest unforeseen costs are usually land acquisition

costs. Although an oil palm company has fulfilled their obligation to the state for land acquisition,

however, in many cases the company has to pay also certain amount of compensation to the local people.

The compensation amount is often unpredictable and varies from place to place depend on several factors,

e.g. customary rules, values of the vegetation covers, access to the roads, and personal negotiations.

Regulatory

The plasma farmers or independent smallholders, who have had land ownership certificate (SHM), have

low risk due to regulations, such as changing of regional spatial plan (RTRW). The highest regulatory risk

is belonged to plasma farmers and independent smallholders, who owned lands with the legal status of

SKPT. The regulatory risk is high because the legal status of SKPT is very weak. The lands with SKPT

document, in some cases are not “clear and clean”. To improve the status of SKPT to become SHM, the

land has to be free of conflicts with the state lands (e.g. state forests), customary lands, or private lands.

The legal land status of the oil-palm company is usually HGU – a temporary use right of land for business

purpose. A company may ask extension of HGU after certain period, however, it is no guarantee for the

extension. Since the new draft of RTRW of the Central Kalimantan Province have not yet been approved

officially, then the uncertainty of land uses in this province is high.

Table 2-7: Comparison of business risks for different types of oil-palm operations

Types RISKS

RSPO certified company

Risks of investment could be adjusted by evaluating the influence of the fluctuations of costs and benefits

in oil-palm management towards financial indicators. Table 2.8 shows that the benefit factor’s

components, i.e. production and price, are more sensitive than the cost components in the oil-palm

operation of independent smallholders, but less sensitive to plasma farmers.

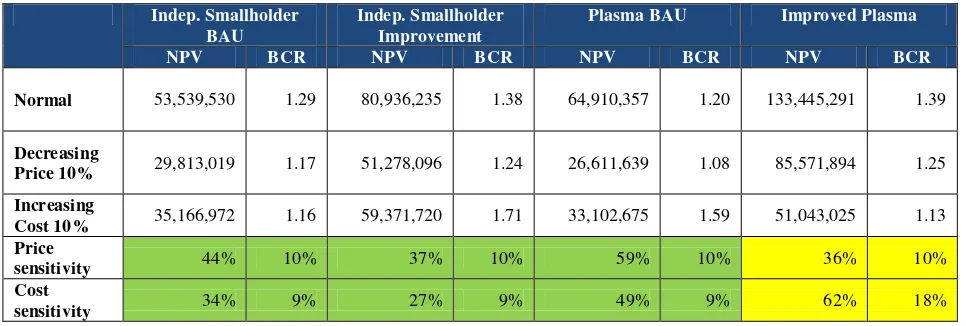

Table 2.8. Comparison of business risks for different types of oil-palm operations

Indep. Smallholder

smallholders by 44%, while decreasing costs of 10% will reduce 34% of profit. The same pattern could

be seen also at the improved independent smallholders and plasma farmers, as well as companies (Table

2.9). The improved plasma farmers, however, has an opposite pattern. For improved plasma farmers, the

cost factors are more sensitive than price factors. Therefore, it is supposed that costs effectiveness

strategy, e.g. controlling input prices, will be effectively applied for improved plasma farmers.

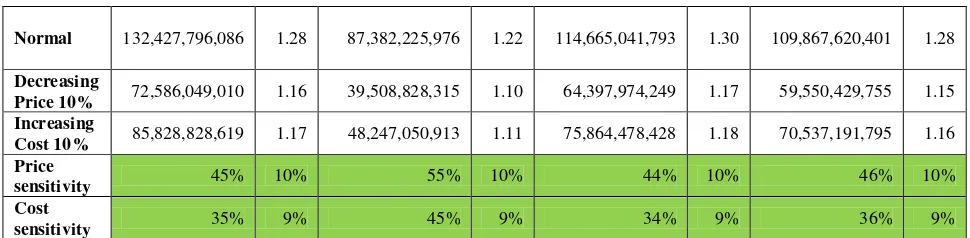

Table 2.9. Comparison of risk adjusted returns for different types of oil-palm operations

Normal 132,427,796,086 1.28 87,382,225,976 1.22 114,665,041,793 1.30 109,867,620,401 1.28

L. Financing gap to go from BAU to Alternatives

As was discussed, it is clearly shown that the alternatives of oil-palm operations, i.e. improvement of

agricultural practices would create much more profit rather than the usual operation (BAU). To

implement those alternatives, additional amounts of capital are needed. This study indicates that to

increase profit of the independent smallholder (5 ha) by IDR 59 million, an additional capital of ca. IDR

39 million is needed. For plasma farmer (5 ha), additional inputs of IDR 27 million will increase the

benefits of IDR 95 million (Table 2.10).

Table 2.10. Financing gap between BAU and Alternatives of oil-palm estate operations by independent smallholders and plasma farmers (unit of 5 ha)

Components

application of RSPO in a company (5,000 ha) will reduce total costs of IDR 77 billion due to decreasing

plantation and harvesting costs of HCV area (ca. 20% of total area of plantation). However, the land

allocation for HCV area (ca. 1,000 ha) will decrease plantation and production volume, which affected to

Table 2.11. Financing gap between BAU and Alternatives of oil-palm estate operations by companies

Components Company BAU

(IDR)

Certified Company Premium Price

(IDR)

GAP

Certified Company Premium Price

(IDR)

Certified Company Premium Price+Carbon

(IDR)

GAP

COSTS df 15% 465,989,674,675 388,005,633,646 (77,984,041,029) 388,005,633,646 393,304,286,052 5,298,652,406

BENEFITS df 15% 598,417,470,761 502,670,675,439 (95,746,795,322) 502,670,675,439 503,171,906,453 501,231,014

Serious efforts should be done to enhance the attractiveness of RSPO certification as well as HCV

management (environmentally based oil-palm plantation), among others by first, increasing premium

price at a profitable level and second, making a simple mechanism and more reasonable price for carbon

credit scheme for the HCV areas of oil-palm plantation. These situations show that oil-palm industries

are “demand side dependent’. In the absence of these two demand signals, i.e. no companies/countries

who buy palm oil pay premium and no carbon emitting countries set cap and create demand for carbon

credits, then a “supply side” strategy has to be formulated by oil-palm producers/countries. The most effective strategy for the oil-palm producers is by controlling supply. Thus, a quota control has to be

applied in oil-palm export policy. To make quota control work, a “joint marketing body” or JMB is

needed. The JMB has to play as “Indonesia incorporated”, who control production and export quota of the

entire oil-palm companies in Indonesia. The more numbers of the member, the more effective the JMB

is. By controlling the production and export quota, then the international price of oil-palm will be less

influenced by “derivative market”, but will be strongly determined by “real market” of supply and

demand. To make strategy more effective, the JMB of Indonesia shall make coordination with other

major oil-palm producers, such as Malaysia, then in the future oil-palm producers could become a “price

Delivery Mechanism

For the implementation of the two proposals namely (i) improving palm oil productivity and (ii) using the

degraded lands for establishment of new palm oil plantations, we conducted a number of analysis. First

analysis was the assessment of financing mechanisms options which are available for supporting to

implementation of the first proposal. Second analysis was the assessment of available land for the

implementation of the two proposals. Third analysis was delivery mechanisms for the implementation of

the two proposals. The following sections discussed the results of the analysis.

A. Financing mechanism options

Regular capital

Financing mechanism for oil-palm estate in Indonesia at current situation is usually coming from regular

capital, i.e. banking credit scheme with commercial rate (+/- 15% per annum). Commonly, small scale

farmers (independent smallholders or plasma farmers) are taken a credit scheme to the Bank for planting

and operational costs of their oil-palm estates. Large scale companies, however, have various behaviors

in financing their oil-palm estates. Those differences are mostly due to the suitability of site for oil-palm

estate. Usually demand of company to take commercial credit for oil-palm estate will increase when the

quality of site is poor. The better suitability of site, the lower the demand of oil-palm company to ask

commercial credit scheme21.

Grants

Officially there are no grants applied in oil-palm sectors. Unofficially, some independent smallholders

developed their oil-palm plantation in the state forest areas. In such cases, instead of spending IDR 2.5

million per hectare for acquisition of farmland, some smallholders did not need “acquisition costs” for their farm lands. It means those farmers get an unofficial “grant” of farmland, although they still need additional costs for land clearing and land preparation. It might profit for some smallholders but doesn’t

fit for companies because they have to fulfill official letter of land use right (HGU).

21

Personal communication with KN, general manager of an oil-palm company.

Loans

Loans are usually given to the oil-palm estate holders through the following schemes:

1) Gestation period of four years

The oil-palm estate holders, either companies or farmers, commonly take a ten year-credit

scheme with commercial rate but the Bank gives a gestation period of payment until four years.

The oil-palm holders start to pay their credit after their farm yielded, usually after four years old

of the plants.

2) Lower interest rate

Lower interest rate is applied only for farmers who participated in the “revitalization program” of

oil palm estate. This program is purposed to improve productivity of small scale oil-palm

plantation by applying better quality of seeds, appropriate fertilizers, and better maintenance of

farmlands. To attract more farmers (independent smallholders and plasma farmers) to participate

into this program, government asked to the Bank or other financial institutions to offer soft loan

scheme (ca. 5%).

Provision of inputs

Provision of inputs, e.g. high quality of seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides are given by a partner company to

the farmers in the context of joint operation of “plasma-nucleus” estate scheme.

Provision of free extension service

Free extension services are given by government and companies to farmers. Usually local government,

i.e. regency agricultural service, provides extension in agricultural productions to farmers in the villages.

The expertise of the government extension worker is usually not specific to certain commodity but for all

agricultural products. The company extension workers have more specific expertise, based on

commodity, e.g. oil-palm. The company usually also provides extension worker to strengthening

institutional capacity of farmer’s groups through joint management of “plasma-nucleus” scheme,

community development program or corporate social responsibility.

Risk guarantees

No official risk guarantees for oil-palm estate, however, factually risks for oil-palm estate operation is

handed over by banking institution who giving credit to the estate holders. If the bank has agreed to

has guaranteed the risks of operation during the credit period. Some companies are also protected by

business insurance to cover risks from diseases or fires. Some other company and small holder farmers

must hand over the risks by themselves, since they did not ask credit to bank nor be protected by

insurance.

Guarantees of purchase

The guarantees of purchase are usually given by a company to his partner farmers through farmer group

or cooperatives. No guarantees of purchase from company for independent farmers (non-partner farmers).

Government, however, only gives a guarantee of purchase for staple foods such as rice but no purchasing

guarantee for oil-palm product.

Differentiated pricing

Prices of oil-palm are mostly influenced by the quality of fruits (size, age, etc.). The price is also

different in the each stage of marketing channels.Theoreticallythe premium price will be given to certified

oil-palm products, however, in reality not many companies nor farmers in Indonesia have been enjoying

the premium price.

Certification schemes

Nowadays many oil-palm estate companies in Indonesia have been preparing for RSPO certification.

Some of them have been certified by third party for the compliance to the RSPO standard. Besides RSPO

standard, since 2011 the government of Indonesia has also released the national oil-palm business

operation standard, namely Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) standard. The ISPO certification is

an obligatory task for all oil-palm company in Indonesia.

Company commitments

More and more oil-palm companies committed to implement sustainable principles in their

business operation. Many companies prepared for a voluntary certification of RSPO, the other

ones committed to practice sustainable principles under national standard of ISPO. Some of

them applied both RSPO and ISPO standards to ensure the acceptance of their products both in

international and domestic market.

plantation companies will obtain the ISPO certificates by 2014. With this regulation, all palm oil

plantation companies will be obliged to conserve High Conservation Values (HCV) areas in their

concession and to apply good practices in reducing GHG emissions and also obliged to develop

plasma farmer with minimum area of 20% of the total area of the plantation.

Obligation for establishing plasma farmer may face dilemma, especially for the existing

established plantation as all their plantation area already planted. To meet this obligation the

alternative ways is to find additional lands to be used for plasma.

B.

Analysis of Land Availability for Establishment of Palm Oil Plantation

Analysis of land availability is divided into two parts. The first part is the assessment of lands which

have been licensed for forest concessions and palm oil plantation. This analysis was aimed to determine

fraction of the licensed lands that have not been planted and not covered by forest. The second part is the

assessment of suitability of unlicensed lands for palm oil plantation in both forest and non-forest areas. In

Indonesia, lands in forest area are under the authority of Ministry of Forestry, while lands in non-forest

area are under the authority of local government. The forest area can be divided into four categories

based on its function namely Production Forest (HP), Convertible Production Forest (HPK), Protection

Forest (HL) and Conservation Forest (HK). Based on regulation, only HPK that can be released to local

governments to become non-forest area and be utilized for non-forest based activities (infrastructure,

settlements, agriculture development etc. or called as APL). In this context, lands in forest area are not

necessary always covered by forest, while lands in non-forest area may also be covered by forest.

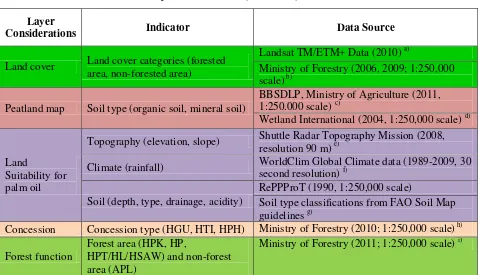

The flow of analysis for assessing lands allocated and suitable for palm oil plantation follows Figure 3.1.

The assessment of suitable land for palm oil was done only for mineral soils using various layer

considerations and indicators (Table 3.1). Layer considerations include land cover, peatland, land

suitability, concessions and forest function. Land cover refers to observed biophysical cover of the earth

surface including a class of vegetation and a type of manmade features as well as bare soil and water body

surfaces. The land cover was derived from Landsat images of year 2010 downloaded from USGS Global

Visualization (http://glovis.usgs.gov/) using land classification system developed by Ministry of Forestry and also used land cover maps (Peta Penutupan Lahan) 2006 and 2009 from Ministry of Forestry. The

land cover maps consist of 22 land use/cover categories, i.e. primary drayland forest, secondary drayland