SURVEY

The evolution of aquaculture in African rural and economic

development

Randall E. Brummett

a,1, Meryl J. Williams

b,*

aInternational Center for Li6ing Aquatic Resources Management Egypt,PO Box 2416,Cairo, Egypt bInternational Center for Li6ing Aquatic Resources Management Headquarters,PO Box 2631,0718 Makati City,

Metro Manila, Philippines

Received 22 January 1999; received in revised form 5 August 1999; accepted 27 October 1999

Abstract

In Africa, aquaculture has developed only recently and so far has made only a small contribution to economic development and food security. We review developments and identify constraints to the expansion of aquaculture in economic and rural development at the continental, national and farm levels. Past development initiatives failed to achieve sustainable increases in production. In contrast, a growing number of smallholder farmers in many countries have been adopting and adapting pond aquaculture to their existing farming systems and slowly increasing their production efficiency. An evolutionary approach that builds on a fusion of local and outside participation in technology development and transfer appears more likely to produce fish production systems that are more productive and more environmentally and socially sustainable in the long term. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Aquaculture; Africa; Rural development; Food security; Integration; Evolution of aquaculture

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. Introduction

Although tilapia may have been cultured in Egypt as long as 2500 years ago, there is little tradition of fish culture in most African countries (Bardach et al., 1972). Though this novelty

ap-plies in varying degrees to many fish farming regions, when coupled with the severe political and socioeconomic constraints facing African agriculture in general, the result is an aquaculture sector that makes only a small contribution to food security and economic development. This is despite Africa’s natural endowments of high-po-tential aquatic genetic resources and adequate water in many parts (Kapetsky, 1994, 1995). This situation may now be changing, brought about by * Corresponding author. Tel./fax: +63-2-812-3798.

E-mail address:[email protected] (M.J. Williams) 1ICLARM Contribution Number 1381.

R

.

E

.

Brummett

,

M

.

J

.

Williams

/

Ecological

Economics

33

(2000)

193

–

203

194

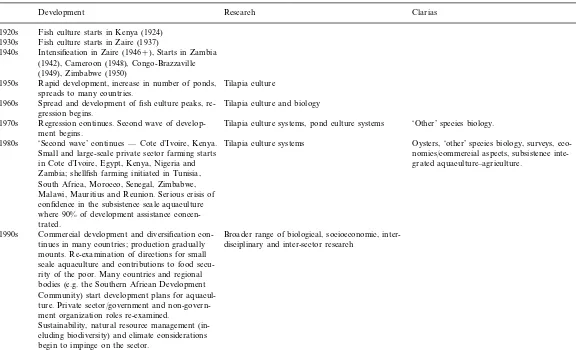

Table 1

Milestones in African aquaculturea

Research

Development Clarias

Fish culture starts in Kenya (1924) 1920s

1930s Fish culture starts in Zaire (1937)

1940s Intensification in Zaire (1946+), Starts in Zambia (1942), Cameroon (1948), Congo-Brazzaville (1949), Zimbabwe (1950)

Rapid development, increase in number of ponds, Tilapia culture 1950s

spreads to many countries.

1960s Spread and development of fish culture peaks, re- Tilapia culture and biology gression begins.

‘Other’ species biology. Regression continues. Second wave of

develop-1970s Tilapia culture systems, pond culture systems

ment begins.

Oysters, ‘other’ species biology, surveys, eco-‘Second wave’ continues — Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya.

1980s Tilapia culture systems

Small and large-scale private sector farming starts nomics/commercial aspects, subsistence inte-in Cote d’Ivoire, Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria and grated aquaculture–agriculture.

Zambia; shellfish farming initiated in Tunisia, South Africa, Morocco, Senegal, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mauritius and Reunion. Serious crisis of confidence in the subsistence scale aquaculture where 90% of development assistance concen-trated.

Broader range of biological, socioeconomic, inter-Commercial development and diversification

con-1990s

disciplinary and inter-sector research tinues in many countries; production gradually

mounts. Re-examination of directions for small scale aquaculture and contributions to food secu-rity of the poor. Many countries and regional bodies (e.g. the Southern African Development Community) start development plans for aquacul-ture. Private sector/government and non-govern-ment organization roles re-examined.

Sustainability, natural resource management (in-cluding biodiversity) and climate considerations begin to impinge on the sector.

a combination of increasing demand for food and other goods from the finite natural resource base and efforts by farmers, researchers, national gov-ernments and development assistance agencies. We examine the evolution of African aquaculture at continental, national and farm levels, and pro-pose ways in which its rate of development may be speeded up yet avoid the environmental pitfalls

of some rapid aquaculture development

elsewhere.

2. Aquaculture development

2.1. Continental and national de6elopments

While still small, African aquaculture produc-tion has entered a steady phase of expansion. Reported production of 121 905 tons in 1997 is more than three times the level of 36 685 tons reported by the Food and Agriculture Organiza-tion of the United NaOrganiza-tions (FAO) in 1984. While the output of capture fisheries has stagnated at about 8 kg per person, aquaculture’s contribution, while still very low at about 1.3% of total fish intake, doubled from 50 g per person in 1984 to 100 g per person in 1992 (FAO, 1995).

Freshwater production dominates in Africa. One-third of total production is from tilapias, especially Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus).

Al-most half of the total reported production from African aquaculture came from Egypt. However, between 1984 and 1997, the number of countries reporting production of over 500 tons per annum increased from two (Egypt and Nigeria) to 11 (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Madagascar, Morocco, Nigeria, Seychelles, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, and Zambia). The sector is also diversifying. In 1997, 42 coun-tries produced 65 different species, or species groups compared to 36 countries reporting 26 species or species groups in 1984 (Source: FAO statistics). Overall, the recent trends fit the pattern of development described by Powles (1987) and extended to the present in Table 1. The table also illustrates how recent a phenomenon aquaculture development is in Africa.

2.2. Farm le6el

Aquaculture presently plays two roles in

African economies: commercial development and rural development. Commercial enterprises are based on an agribusiness approach and usually culture high value species fed prepared diets. Both investment and profit are measured only in cash. Aquaculture provides jobs, earns or saves foreign exchange and creates wealth for the investors. They tend to focus on export or local luxury markets. Under Katz’s (Katz, 1995) scheme, com-mercial aquaculture would be labeled as an emer-gent sub-sector (less than 1000 tons production and relatively few species) in most African coun-tries. In Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa, it would be classified in the established but simple sub-sector. The main constraints to the develop-ment of a more commercialized and productive aquaculture sector are common to most agribusi-ness in Africa (Table 2).

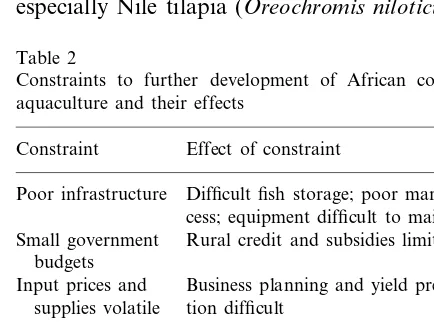

Aquaculture for rural development involves production systems operated by smallholding farmers and based on locally available pond in-puts and species that are easily grown and repro-duced. Investment is in the form of land, water and labor. Impact is measured as food security, poverty alleviation, an improved rural environ-ment and greater farm output and stability. The main production system is the small pond of Table 2

Constraints to further development of African commercial aquaculture and their effects

Constraint Effect of constraint

Poor infrastructure Difficult fish storage; poor market ac-cess; equipment difficult to maintain Small government Rural credit and subsidies limited

budgets

Input prices and Business planning and yield predic-supplies volatile tion difficult

Threats to economic viability of en-Political instability

terprise and security of investment and investors

Poverty of con- Small local markets; reliance on ex-sumers ternal markets

Lack of local ex- Increases risk; limits range of techni-cal options

R.E.Brummett,M.J.Williams/Ecological Economics33 (2000) 193 – 203

196

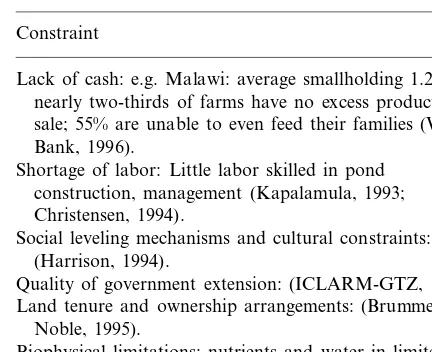

Table 3

Common constraints to further development of African aqua-culture for rural development

Constraint

Lack of cash: e.g. Malawi: average smallholding 1.2 ha; nearly two-thirds of farms have no excess production for sale; 55% are unable to even feed their families (World Bank, 1996).

Shortage of labor: Little labor skilled in pond construction, management (Kapalamula, 1993; Christensen, 1994).

Social leveling mechanisms and cultural constraints: (Harrison, 1994).

Quality of government extension: (ICLARM-GTZ, 1991). Land tenure and ownership arrangements: (Brummett and

Noble, 1995).

Biophysical limitations: nutrients and water in limited supply and/or highly seasonal in availability (Brummett, 1997).

and nutrient levels are manipulated to enhance returns to capture fisheries. Small waterbodies of less than 20 ha are the most common targets of these strategies, but larger reservoirs, coastal lakes along the Mediterranean and inland flood plains have also been put forward as having potential (Coates, 1995; De Silva, 1995). Introductions such

as the small pelagic kapenta (Limnothrissa

miodon) into Lake Kariba have produced signifi-cant fisheries, although other introductions have had catastrophic consequences for indigenous bio-diversity (e.g. of the Nile perch (Lates niloticus) into Lake Victoria). Estimates of the optimal potential yield from small waterbodies in sub-Sa-haran Africa alone range about 1 million tons per year (Coates, 1995). Little additional technical knowledge is required to achieve large gains, al-though environmental degradation, loss of biodi-versity, lack of good management regimes and socioeconomic factors could be major constraints (Pitcher and Hart, 1995).

3. Lessons from the past: getting the right assistance to the farmer

Because of their rural development context, yet commercial orientation, the smallscale commer-cial sector has been the logical point of

interven-tion for the international development

community. During the 1980s, about 90% of the international assistance to African aquaculture went to this group (Huisman, 1990). On average, overall assistance was US$18.28 million per year for the period 1985 – 1989 (Insull and Orzeszko, 1991). This was 11% of total assistance to aqua-culture worldwide, for negligible measured im-pact. More than 300 assistance projects were initiated from the early 1970s to the early 1990s. They concentrated on extension, training and building state farms and hatcheries. They stressed proven technology imported from established in-dustries. However, these were often introduced with insufficient regard for the prevailing social systems, economic conditions, the indigenous knowledge base and natural resource constraints. Harrison et al. (1994) reviewed the generally dis-mal record of this assistance, confirming earlier

200 – 500 m2 fed with unprocessed agricultural

by-products. Fish are produced for home con-sumption or for the local barter economy. Little or no cash is involved. Although different from those faced by commercial producers, the poten-tial constraints to production by smallholders are likewise formidable (Table 3).

These two main sectors of aquaculture are not sharply differentiated and a continuum of systems exists. Characterizing the various stages within the continuum helps the formulation of policies and development interventions. For example, a third, intermediate, type of aquaculture enterprise can be identified in some countries. These enterprises are often referred to as ‘small-scale commercial’. Farmers in this group may represent a step in the transition from the rural development sector to more commercial aquaculture. Compared to those in the rural development sector, these farmers purchase a greater proportion of inputs and sell more of their products for cash. They differ from purely commercial systems by retaining their so-cial connections to the local community. Main-taining this balance is extremely difficult in poor African communities and, consequently, success stories are scarce.

reviews (e.g. King and Ibrahim, 1988; Huisman, 1990). The loss of confidence in small-scale com-mercial aquaculture led to considerable debate over solutions and reluctance among the assis-tance community to fund further work in any type of aquaculture.

That these projects have not resulted in large, sustained increases in fish production, however, does not necessarily mean that aquaculture, per se, is a nonviable proposition in Africa. It is more likely that the point of entry and modus operandi for earlier development projects was incorrect. One proof of this is that aquaculture among smallholders has recently been expanding across the continent (Nathanae¨l and Moehl, 1989; Mol-nar et al., 1991; van den Berg, 1994; Campbell, 1995; Murnyak and Mafwenga, 1995; Ngenda, 1995). These new projects have been based on participatory and evolutionary approaches and a rural development focus as recommended in the thematic evaluation of aquaculture (FAO/NO-RAD/UNDP, 1987).

Over the course of rural development, changes in land use, family and social structure may, in fact, be unavoidable. Smallholder aquaculture may cause problems associated with changes in internal household dynamics and community rela-tionships resulting from activities of rural devel-opment practitioners (Harrison, 1994; Harrison et al., 1994). Relatively better off farmers tend to be early adopters and major beneficiaries (e.g. Har-rison, 1994).

However, recent experience has shown that, if sensitivity to the needs and problems of the user group can be built into development activities, these problems might be minimized. User friendly approaches can also speed technology uptake (Brummett and Noble, 1995; Brummett and Chikafumbwa, 1998) and engender a spirit of innovation that can cause small-scale farming sys-tems to evolve (Chikafumbwa, 1995).

4. Future food security, fish supply and demand

Population increase and economic growth are the two most important factors that affect the demand for food fish (Westlund, 1995). In the

current African situation of high population growth and economic stagnation, the former will most likely be the dominant factor, especially considering the relative inelasticity of demand for cheap fish in many markets (Delgado, 1995). The 1990 African population of 800 million is ex-pected to reach 1066 million by 2010, requiring 9.6 million tons of fish compared to 5.2 million tons in 1990 (Westlund, 1995). Capture fisheries that have been essentially static since 1987 will not be able to meet this demand (FAO, 1995).

Although unlikely to happen by 2010, aquacul-ture could still make a significant contribution towards filling the gap. Based on projections of past growth trends, Bonzon (1995) predicted that aquaculture production in sub-Saharan Africa would reach 80 000 tons by 2000 and 320 000 tons in 2010. Similarly, Satia (1991) predicted a total aquaculture output of 100 000 tons for all of Africa by 1995 – 1996.

Recent projection methods that use newer ap-proaches and successes, however, are more

opti-mistic about the potential. Using very

conservative production figures, Kapetsky (1994) estimated that 31% of sub-Saharan Africa (40

countries, 9.2 million km2

) is suitable for small-holder fish farming. Extrapolating from more re-cent smallholder, development-oriented projects, Kapetsky (1995) goes on to estimate that this sub-sector alone could meet 35% of Africa’s in-creased fish need up to the year 2010 on only 0.5% of the total area potentially available. Kapetsky (1994) also found that, of the land suitable for subsistence fish farming, almost 1/3 is also suitable for commercial aquaculture. Aguilar-Manjarrez and Nath (1998) reassessed the poten-tial at a finer resolution and found that between 37 and 43% of the African land surface contains areas suitable for small-scale and commercial fish farming of the three main freshwater species,

namely O. niloticus, Clarius gariepinus (African

catfish) and Cyprinus carpio (common carp).

disrup-R.E.Brummett,M.J.Williams/Ecological Economics33 (2000) 193 – 203

198

tion have followed the rapid and indiscriminate expansion of aquaculture in other parts of the world. Cage culture of carnivorous fishes in Japan, Hong Kong and Northern Europe, for example, has resulted in severe water pollution (Csavas, 1993). Clearing of mangroves and inten-sification of shrimp farming has caused erosion, loss of fish habitat, soil acidification and saliniza-tion (Beveridge et al., 1994, 1997) and displaced small-scale fishers and farmers in many coastal areas in Asia and Latin America (Primavera, 1997). Similar growth patterns in Africa may solve some short-term economic problems, but at a cost that may be unsupportable in the longer term. More commercial fish production systems will most certainly develop and thrive, but to justify intervention on the part of the interna-tional community, the model for this development must take into consideration the important issues of equity and sustainability.

5. Promoting evolution at the farm level

The efficacy of a rural development strategy in equitably addressing food insecurity depends upon increasing the numbers of producers and then incrementally improving individual farm out-put through on-farm evolution of technologies that are both more productive and also preserve the integrity of the environment. To achieve this requires supportive policies and user-inclusive technology development and transfer mecha-nisms. It also requires a revaluation of

environ-mental goods and services provided to

aquaculture (Berg et al., 1996).

The existing spectrum of African aquaculture systems is the result of variable environmental, social and economic conditions (Brummett and Haight, 1997). This variety precludes mass appli-cation of technology. Early development projects failed to recognize this and attempted to import more or less uniform technology packages or modules. Little effort was made to transfer the basic principles of aquaculture to farmers and extension personnel. This resulted in a limited ability to flexibly adapt technology to particular situations. Without an understanding of

princi-ples, even those farms that could use a technology package were constrained in their ability to evolve into more productive systems.

Recent African success stories show that aqua-culture is more likely to be sustained where it is called for as a component of broader, integrated rural development initiatives. Leadership that comes from local actors rather than from develop-ment agencies garners more and longer-term sup-port. This should lead to the evolution of practices that meet the needs of both rural com-munities and national budgets. The aquaculture industries in Scotland, Norway (Aarset, 1997), South Africa, Israel and the USA (Perez, et al., 1996) have followed such an evolutionary path-way from a beginning among relatively

small-scale entrepreneurs working closely with

university and/or government researchers to im-prove output and markets over time. Government policies and assistance often followed.

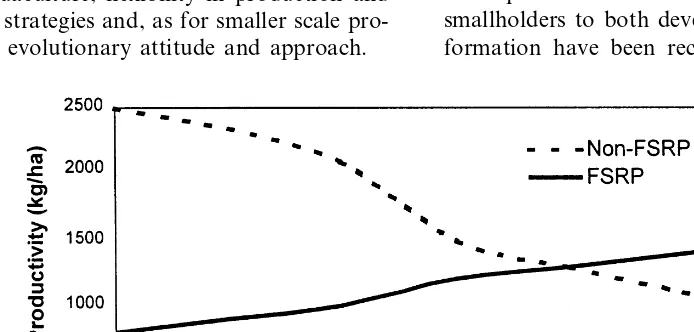

In Africa, engendering an evolutionary ap-proach will require a new interactive relationship between researchers and farmers (Brummett and Haight, 1997). This evolution will most profitably begin at the smallholder level where the majority of agriculture producers operate. A likely entry point is the integration of aquaculture into exist-ing farmexist-ing systems. Research in Malawi (Stew-art, 1993; Brummett and Noble, 1995; Scholz and Chimatiro, 1995) and Ghana (Prein, 1994; Rud-dle, 1996) has shown that a fish pond integrated into a farm in such a way that it recycles wastes from other agricultural and household enterprises can increase production and profitability. As farmers gain a greater understanding of how this new system functions and an appreciation of its potential, they become increasingly able to guide further evolution towards increasing productivity and profitability (Brummett and Noble, 1995; Brummett and Chikafumbwa, 1998). Fig. 1 illus-trates this phenomenon for a group of farmers in Malawi.

contin-uum has the additional potential advantage of minimizing problems of inequity in access to the produce of aquaculture. Many smallholders lack the means to buy fish in the open market, but can get access to a significant proportion of the fish grown in smallholder systems. These are bartered or consumed directly by the farm family (Brum-mett and Chikafumbwa, 1995).

When they evolve from local initiatives rather than being imposed from outside, even small-scale commercial producers may be locally successful (ALCOM, 1994) and, being further along on the development continuum, might quickly grow into even larger scale commercial systems, which can give larger increases in production in the short term. These might be expected to compete with cheap imports rather than focusing on export markets thus increasing the availability of valu-able protein for indigenous consumption. The key to success will be in filling the small and diverse niches within both the local and export markets. To do this requires a reliance on the basic princi-ples of aquaculture, flexibility in production and marketing strategies and, as for smaller scale pro-ducers, an evolutionary attitude and approach.

6. Engendering evolution at the national level

Africa has the natural resources to support an aquaculture evolution. Population growth in rural and urban areas opens up potential outlets for smaller scale producers who can grow low-value species if they can start small, rely on locally available inputs and be brought close to the market.

The role of government needs to be redefined (Lazard et al., 1991), especially as government resources contract (ALCOM, 1994) and as the need to broaden fisheries and agriculture policies to include aquaculture is more widely recognized (Satia, 1989). Appropriate roles for the govern-ment are to coordinate national planning, provide appropriate infrastructure support (e.g. roads to market), research, extension and information services.

New approaches that amalgamate the capacities of research and extension to form technology development and transfer entities that work with smallholders to both develop and disseminate in-formation have been recognized as crucial (van

R.E.Brummett,M.J.Williams/Ecological Economics33 (2000) 193 – 203

200

der Mheen, 1996). Training in participatory ap-proaches can help target projects towards the needs of different households (Harrison et al., 1994). Williams (1997) concluded that participa-tory research and extension would be the relevant approaches to improve adoption and development where aquaculture is not well developed and not traditionally used. In aquaculture extension, the technically competent non-governmental organi-zations can play an important role. Research aimed at smallholders should focus on technolo-gies that facilitate the introduction of aquaculture into existing farming systems. These would in-clude methods for storing and processing agricul-tural by-products and the identification of new indigenous species for culture.

Commercial aquaculture will be constrained by lack of access to information and credit and will benefit by better and more commercial operation of seed production, more specialized training of research and extension personnel, reorganized public administration and better databases for planning and evaluation (Coche et al., 1994). Bet-ter fish species and strains and more efficient feeding systems would be valuable contributions from research.

Close cooperation between government agen-cies and between research and extension teams is required. At the national level, development assis-tance agencies should align their assisassis-tance poli-cies and programs so as to encourage the evolutionary approach with strong local participa-tion and investments in wider research and knowledge.

7. Outlook for African aquaculture development

African aquaculture is still in an early stage of development due to: (1) the lack of a tradition of fish and water husbandry, (2) numerous social, economic and political constraints that limit in-vestment and retard expansion and, (3) the fact that only in recent years have appropriate devel-opment models been employed to foster growth. On the other hand, the increasing demand for fish in Africa, the real achievements to date and the results of studies of market and natural resource

potential indicate that aquaculture still has great potential to contribute to food security rural de-velopment and economic growth.

To improve the contribution from aquaculture, we recommend an integrated, evolutionary and multi-level approach. We suggest combining the methods currently evolving among African small-holders with additional support to outreach and research focused on integrated resource manage-ment and the diversification and enhancemanage-ment of cultured germplasm. The aim of this joint action should be to develop farming systems that pro-duce more fish while retaining their environmental and social sustainability.

The opportunities presented by aquaculture will only be realized if supported by national policies and programs and if capitalized upon by local and international development agencies. Other practices, such as the transfer of standard technol-ogy packages without knowledge of local

condi-tions and the importation of large-scale

commercial turn-key projects, could have negative environmental and social consequences, as wit-nessed elsewhere, and could threaten food and security globally (Harremoe¨s, 1996; Harris, 1996). We expect that smallholder aquaculture, inte-grated at first with existing agriculture, will tend to evolve toward partly or completely commercial systems as the demand for fish increases. Small-scale commercial systems will more rapidly ex-pand and diversify to satisfy niche markets and eventually compete with imports. If development efforts take the needs and capabilities of the many potential users into consideration through partici-patory technology development and transfer, di-verse and situation-specific farming systems can evolve into increasingly productive enterprises while maintaining a firm basis in efficient and sustainable resource utilization.

References

Aarset, B., 1997. The Blue Revolution Revisited: Institutional Limits to the Industrialization of Finfish Aquaculture. University of Tromso Thesis for Dr. scient. in Fisheries Science.

ALCOM, 1994. Aquaculture into the 21st Century in South-ern Africa. Report Prepared by the Working Group on the Future of ALCOM. Food and Agriculture Organi-zation of the United Nations, Rome, p. 48, Aquaculture for Local Community Development Program, Report No. 15.

Bardach, J.E., Ryther, J.H., McLarney, W.O., 1972. Aquacul-ture: the Farming and Husbandry of Freshwater and Marine Organisms. Wiley Interscience, New York. Berg, H., Michelsen, P., Folke, C., Kautsky, N., Troell,

M., 1996. Managing aquaculture for sustainability in tropical Lake Kariba, Zimabwe. Ecol. Econ. 18, 141 – 159.

Beveridge, M.C.M., Ross, L.G., Kelly, L.A., 1994. Aquacul-ture and biodiversity. Ambio 23 (8), 497 – 502.

Beveridge, MCM, Phillips, M.J., Macintosh, D.J., 1997. Aqua-culture and the environment: the supply of and demand for environmental goods and services by Asian aquaculture and the implications for sustainability. Aquaculture Res. 28, 797 – 807.

Bonzon, A., 1995. Demand and supply of fish and fish prod-ucts in subSaharan Africa: perspectives and implications for food security. In: Demand and Supply of Fish and Fish Products in Selected Areas of the World: Perspectives and Implications for Food Security. International Conference on Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to Food Security, 4 – 9 December 1995, Kyoto, Japan, pp. 180 – 197 KC/FI/

95/TECH/10 (FAO).

Brummett, R.E., Chikafumbwa, F.J.K., 1995. Management of rainfed aquaculture on Malawian smallholdings. In: PA-CON Conference on Sustainable Aquaculture, 11 – 14 June 1995, Honolulu, Hawaii. Pacific Congress on Marine Sci-ence and Technology, Honolulu, HI, USA.

Brummett, R.E., Chikafumbwa, F.J.K., 1998. An incremental, farmer-participatory approach to the development of aquaculture technology in Malawi. In: Association for Farming Systems Research and Extension, Pretoria, Re-public of South Africa, 30 November – 4 December. Brummett, R.E., Haight, B.A., 1997. Research – development

linkages. In: Martinez-Espinosa, M. (Ed.), Report of the Expert Consultation on Small-Scale Rural Aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome FAO Fisheries Report 548.

Brummett, R.E., Noble, R.P., 1995. Aquaculture for African smallholders. ICLARM Tech. Rep. 46, 69.

Brummett, R.E., 1997. Why Malawian smallholders don’t feed their fish. In: Likongwe, J.S., Kaunda, E. (Eds.), First Regional Workshop on Aquaculture. Bunda College of Agriculture, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Campbell, D., 1995. The impact of the field day extension approach on the development of fish farming in selected areas of western Kenya. Food and Agriculture Organiza-tion of the United NaOrganiza-tions, Kisumu, Kenya TCP/KEN/

4551(T) Field Document No. 1.

Chikafumbwa, F.J.K., 1995. Farmer participation in technol-ogy development and transfer in Malawi. In: Brummett, R.E. (Ed.), Aquaculture Policy Options for Integrated Resource Management in subSaharan Africa. International

Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management ICLARM Conference Proceedings 46.

Christensen, C., 1994. Agricultural Research in Africa: a Re-view of USAID Strategies and Experience. US Agency for International Development, Washington, DC. SD Techni-cal Paper 3, Office of Sustainable Development.

Coates, D., 1995. Inland capture fisheries and enhancement: status, constraints and prospects for food security. In: International Conference on Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to Food Security, 4 – 9 December 1995, Kyoto, Japan, p. 82 KC/FI/95/TECH/3 (FAO).

Coche, A.G., Haight, B.A., Vincke, M.M.J., 1994. Aquacul-ture Development and Research in Sub-Saharan Africa: Synthesis of National Reviews and Indicative Action Plan for Research. FAO, Rome, p. 151, CIFA Technical Paper No. 23.

Csavas, I., 1993. Aquaculture development and environmental issues in the developing countries of Asia. In: Pullin, R.S.V., Rosenthal, H., Maclean, J.L. (Eds.), Environment and Aquaculture in Developing Countries. International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines, ICLARM Conference Proceedings 31.

De Silva, S.S., 1995. CGIAR research priorities revisited: a case for a higher priority for reservoir, lake system re-search. Naga ICLARM Q. 13 (3), 10 – 14.

Delgado, C.L., 1995. Fish consumption in sub-Saharan Africa. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to Food Security, 4 – 9 December 1995, Kyoto, Japan. International Food Policy Research Institute, p. 25.

FAO, 1995. Review of the State of World Fishery Resources: Aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome FAO Fish. Circ. No. 866. FAO/NORAD/UNDP, 1987. Thematic evaluation of

aquacul-ture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Norwegian Ministry of Development Coopera-tion and United NaCoopera-tions Development Program. FAO, Rome.

Harremoe¨s, P., 1996. Dilemmas in ethics: towards a sustain-able society. Ambio 25 (6), 390 – 395.

Harris, J.M., 1996. World agricultural futures: regional sus-tainability and ecological limits. Ecol. Econ. 17, 95 – 115.

Harrison, E., Stewart, J.A., Stirrat, R.L., Muir, J., 1994. Fish Farming in Africa, What’s the Catch? Overseas Develop-ment Administration, p. 51.

Harrison, E., 1994. Aquaculture in Africa: socio-economic dimensions. In: Muir, J.F., Roberts, R.J. (Eds.), Recent Advances in Aquaculture V. Institute of Aquaculture, Stirling, UK.

Huisman, E.A., 1990. Aquacultural research as a tool in international assistance. Ambio 19 (8), 400 – 403. ICLARM-GTZ, 1991. The Context of Small-Scale Integrated

R.E.Brummett,M.J.Williams/Ecological Economics33 (2000) 193 – 203

202

Insull, D., Orzeszko, J., 1991. A Survey of External Assistance to the Fishery Sectors of Developing Countries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome Fish. Circ. No. 755 (Revision 3).

Kapalamula, M., 1993. Comparative Study of Household Economics of Integrated Agriculture — Aquaculture Farming Systems in Zomba, District. Department of Rural Development, Bunda College of Agriculture, University of Malawi MSc Thesis.

Kapetsky, J.M., 1994. A Strategic Assessment of Warm-Water Fish Farming Potential in Africa. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, CIFA Techni-cal Paper No. 27.

Kapetsky, J.M., 1995. A first look at the potential contribu-tion of warm water fish farming to food security in Africa. In: Symoens, J.-J., Micha, J.-C. (Eds.), The Management of Integrated Freshwater Agro-Piscicultural Ecosystems in Tropical Areas. Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation, Wageningen.

Katz, A., 1995. A Study of National Strategies for Aquacul-ture Development. PACON Sustainable AquaculAquacul-ture 95 Meeting Highlights, pp. 14 – 19, Summary report. King, H.R., Ibrahim, K.H. Jr (Eds.), 1988. Village Level

Aquaculture Development in Africa. Proceedings of the Commonwealth Consultative Workshop on Village Level Aquaculture Development in Africa, Freetown, Sierra Leone, 14 – 20 February 1985. Commonwealth Secretariat, London, UK.

Lazard, J., Lecomte, Y., Stomal, B., Weigel, J.-Y., 1991. Pisciculture en Afrique Subsaharienne: situations et projects dans des pays francophone. Ministere de la Coop-eration et du Developpement, p. 155.

Molnar, J.J., Rubagumya, A., Adjavon, V., 1991. The sustain-ability of aquaculture as a farm enterprise in Rwanda. J. Appl. Aquaculture 1 (2), 37 – 62.

Murnyak, D., Mafwenga, G.A., 1995. Extension methodology practiced in fish farming projects in Tanzania. In: Proceed-ings of the Aquaculture for Local Communities (ALCOM) Technical Consultation on Extension Methods for Small-holder Fish Farming in Southern Africa. Lilongwe, Malawi, 20 – 24 November.

Nathanae¨l, H., Moehl, J.F. Jr, 1989. Rwanda national fish culture project. In: International Center for Aquaculture Research and Development Series, vol. 34. Alabama Agri-cultural Experiment Station, Auburn University, AL. New, M., 1991. Turn of the millenium aquaculture: navigating

troubled waters or riding the crest of a wave. World Aquaculture 22 (3), 28 – 49.

Ngenda, G., 1995. Aquaculture extension methods in Eastern Province, Zambia. In: Proceedings of the Aquaculture for Local Communities (ALCOM) Technical Consultation on Extension Methods for Smallholder Fish Farming in Southern Africa, Lilongwe, Malawi, 20 – 24 November. Perez, K., Bailey, C., Waren, A., 1996. Catfish in the farming

system of west Alabama. In: Bailey, C., Jentoft, S.,

Sin-clair, P.R. (Eds.), Aquaculture Development: Social Di-mensions of an Emerging Industry. Westview, Boulder, CO, pp. 125 – 142.

Pitcher, T.J., Hart, P.J.B., 1995. The Impact of Species Changes in African Lakes. Chapman and Hall, London.

Powles, H., 1987. Introduction to the workshop: history and status of African aquaculture research. In: Powles, H. (Ed.), Research Priorities for African Aquaculture: Report of a Workshop Held in Dakar, Senegal, October 13 – 16, 1986. International Development Research Centre, Ott-awa, Canada, pp. 2 – 13 IDRC-MR 129e.

Prein, M., 1994. Farmer participatory development of inte-grated agriculture – aquaculture systems for natural re-source management in Ghana. In: Brummett, R.E. (Ed.), Aquaculture Policy Options for Integrated Resource Man-agement in Sub-Saharan Africa, vol. 46, p. 38 ICLARM Conference Proceedings.

Primavera, J.H., 1997. Socio-economic impacts of shrimp cul-ture. Aquaculture Res. 28, 815 – 827.

Ruddle, K., 1996. The potential role of integrated manage-ment of natural resources in improving the nutritional and economic status of resource-poor farm households in Ghana. In: Prein, M., Ofori, J.K., Lightfoot, C. (Eds.), Research for the Future Development of Aquaculture in Ghana, vol. 42, p. 94 ICLARM Conference Proceed-ings.

Satia, B., 1989. A Regional Survey of the Aquaculture Sector in Africa South of the Sahara. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome ADCP/REP/

89/36.

Satia, B.P., 1991. Why not Africa? Ceres 23 (5), 26 – 31. Scholz, U., Chimatiro, S., 1995. The promotion of small-scale

aquaculture in the southern region of Malawi: a reflection of extension approaches and technology packages used by the Malawi – German Fisheries and Aquaculture Develop-ment Project (MAGFAD). In: Proceedings of the Aquacul-ture for Local Communities (ALCOM) Technical Consultation on Extension Methods for Smallholder Fish Farming in Southern Africa. Lilongwe, Malawi, 20 – 24 November.

Stewart, J.A., 1993. The Economic Viability of Aquaculture in Malawi: a Short-Term Study for the Central and Northern Regions Fish Farming Project, Mzuzu, Malawi Institute of Aquaculture. University of Stirling, UK.

van den Berg, F., 1994. Privatization of fingerling production and extension: a new approach for aquaculture develop-ment in Madagascar. In: Brummett, R.E. (Ed.), Aquacul-ture Policy Options for Integrated Resource Management in Sub-Saharan Africa. ICLARM Conference Proceedings, vol. 46, p. 69.

Westlund, L., 1995. Apparent historical consumption and future demand for fish and fishery products-exploratory calculations. In: Proceedings of the International Confer-ence on Sustainable Contribution of Fisheries to Food Security, 4 – 9 December 1995, Kyoto, Japan, p. 55 KC/FI/

95/TECH/8 (FAO).

Williams, M.J., 1997. Aquaculture and sustainable food secu-rity in the developing world. In: Bardach, J.E. (Ed.), Sustainable Aquaculture. Wiley, New York, pp. 1 – 51.

World Bank, 1996. Malawi Human Resources and Poverty. World Bank, Washington, DC, Report 15437-MAI.