Bibliometrics and urban knowledge transfer

Judith Kamalski

a,⇑, Andrew Kirby

b aElsevier, Radarweg 29, 1043 NX Amsterdam, Netherlands bArizona State University, Phoenix, AZ 85069-7100, USAa r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Available online 5 July 2012

Keywords:

This paper demonstrates the potential of bibliometric analysis in the context of urban studies. After a brief discussion of the measurement of knowledge production, we provide an analysis of how the field of urban studies is constructed. We do this in three contexts: first, in the narrowly defined population of journals that constitutes the Thomson Reuters classification of urban studies; second, in the larger pop-ulation of journals deemed to be within the social and behavioral sciences; and third, in a subset of the applied sciences. We find that, by using keyword analysis, it is possible to identify three distinct spheres of ‘urban knowledge’ that contain some overlap but also significant differences. We explore the signifi-cance of that for the development of urban studies.

Ó2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

To this point, research on the production of knowledge has been dominated by a number of interrelated concerns. The first of these would be what we can think of as the historical and philosophical focus upon the creation of disciplines, and the processes of what have been termed ‘normal science’. A second would be the deter-mination of disciplinary content via the identification of keywords and the construction of thesauri (Broughton, 2006). A third context would be the manner in which methods and procedures have evolved.

These concerns are all marked by their deductive emphasis, placing well-known narratives into commonly-accepted structures (Smolin, 2006). From at least one perspective, this is a teleological approach that tells us how our science has progressed, told from within the same structures of that very science. Little is known of our scientific failures, false starts, and falsification experiments, as they have been placed to one side: it is, if you will, a story told only by winners—those who contribute to the dominant structures of organized science and not by losers—those whose work is seen to be marginalized.

There is, in contrast, a different approach to the production of knowledge that eschews the deductive and the normative in favor of the inductive and the empirical—simply, ‘what is’. In such a con-text, we can focus upon the production of information as it occurs, without having to place any grids of understanding across the pat-terns of transfer.

This approach depends upon, and is facilitated by, the digital transfer of information (e.g. Bollen et al., 2009). In the past, we have been dependent upon relatively rigid methods of investiga-tion into the relainvestiga-tions between those who conduct science: in terms of correspondence, say, or published collaborations. In the present, we have more precise methods of measurement. Using citation analyses, for example, we can construct elaborate dia-grams that show exactly how individuals collaborate, or who cites whom. We can aggregate these, and see how individuals, laborato-ries or ‘science cities’ are connected (or unconnected) in the global flows of information (Bornmann & Leydesdorff, 2011).

We can now also go beyond these structures and examine the links between the component parts of the academy as they exist in practice. For instance, Bollen et al. have analyzed clickstream data to show precisely how researchers research—or alternatively, perhaps, how searchers search (2009). By following the trails of in-quiry—clickstreams—we can see via aggregation which fields and sub-fields are connected. This has almost nothing to do with a pri-ori constructs such as disciplines, philosophies of science or meth-od; instead it is scientific interaction in practice.

Connections within urban studies and why it matters

Urban studies is one of the longest established interdisciplin-ary fields within the modern academy. Indeed, massive urban growth was a backdrop to the foundation of many universities at the start of the 20th century, and a fundamental component of disciplines, such as sociology, that confronted the emergence of modernism as it manifested itself in these new metropolitan settings. Yet this meant that the study of cities was woven into many different disciplines, that had in consequence their own

0264-2751/$ - see front matterÓ2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.06.012 ⇑ Corresponding author. Tel.: +31 204852288.

E-mail addresses:j.kamalski@elsevier.com(J. Kamalski),andrew.kirby@asu.edu

(A. Kirby).

Contents lists available atSciVerse ScienceDirect

Cities

urban specializations—urban anthropology, urban economics and so forth. This has also been true in recent decades of the applied sciences, where meteorology, climate and ecology have all become tightly engaged with the processes of urban development. Nor is this brief overview meant to ignore the humanities, where urban history intersects with the concerns and technologies of the other disciplines.

Yet this richness of material constitutes its own problems. For the most part, urban studies has never been destined to emerge as a freestanding discipline, and in fact its nearest neighbors—such as urban and regional (or town and country) planning—have been in a phase of transformation for many years (Campanella, 2011). It has its own journals of course, and its own subject classification in the Thomson Reuters schema, but these account for only a small proportion of the material published in the broader context of ur-ban analysis (e.g.Liu, 2005). A recent paper documents some of these ways in which the field has evolved over the past two dec-ades (Wang, He, Liu, Zhuang, & Hong, 2012).

This situation has led to two outcomes: first, there is some redundancy in the research that is published in different sub-fields but overall, there is little convergence between the different strands of urban research. This is especially true when different methodologies and/or different ideological outlooks are factored in. Second, and in consequence, it is a challenge for researchers to maintain any systematic awareness of work being done in dis-tant fields, albeit with similar urban content: this is especially true of research in transport, ecology, risk management and climate change.

Research strategy

In order to explore these issues systematically, we examined the convergences and divergences in the different branches of ur-ban research. First, we identified three distinct clusters of pub-lished material:

1. the research published within the 38 journals that constitute the urban studies cluster within the Thomson Reuters classifi-cation of research journals;

2. the research published within the journals that together pub-lish urban material from the social sciences and the humanities; 3. the research with urban content published in the applied

sciences.1

In the SciVerse-Scopus database of journal articles published in 2010, which contains 991,000 entries, we identified research pa-pers containing the keyword ‘urban’ plus one of the following key-words—planning, renewal, development, politics, population, transport, housing—that have shown up in a pilot project. (Papers without these keywords tend to be focused on research undertaken in cities rather than rural areas, but are not adding to urban schol-arship as such.)

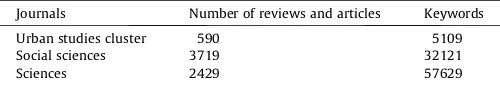

We limited the search to social science subject areas and to rel-evant subject areas in the applied sciences. We ignored medicine, engineering and similar fields as this research was, once again, undertaken in urban contexts but did not contribute to urban scholarship; a typical example would be technical studies of atmo-spheric chemistry that use urban and rural samples but have no policy content. This yielded the following numbers of articles and reviews (seeTable 1).

As a second step of our analysis, we looked at frequencies of keywords attributed by indexers such as MEDLINE and Embase. Redundancies were eliminated and minor categories collapsed: e.g. ‘water use’ and ‘water planning’ were aggregated to ‘water’. The three data sets were rearranged according to the keyword fre-quency, and scaled against the grand totals for each column, in or-der to make the columns comparable (e.g. 502 as a proportion of 32121 = 156, the first entry in the social sciences column).

Results

InTable 2we show the top twenty rankings of the aggregated key words for the three groups of journals. In red we indicate key-words that are unique to a single column; in blue we show those that are shared across all three columns.

The table indicates that there is a high degree of divergence be-tween the three groups of journals, with 21 of the keyword entries being unique and only 20 appearing on all three lists; in a situation of complete convergence there would be a total of only 20 entries, in a situation of total divergence there would be 60 unique entries. The social science journals show the least individuality, with only three unique keywords. The applied science journals display an emphasis on research on urban areas that is linked to environ-mental issues; keywords include air, atmosphere, water and the environment itself. In addition, this column contains the very spe-cific policy component—sustainability. The urban column stands in marked contrast, beginning with housing and continuing through topics such as urban renewal.

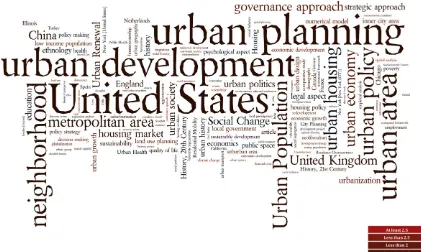

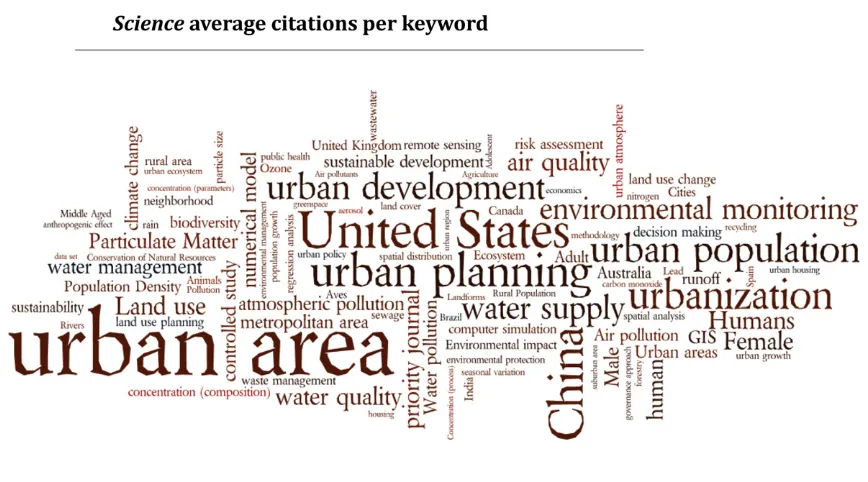

We also examined all the keywords in terms of their frequency of appearance, and the frequency of citation. These are displayed in Figs. 1–3.

Assessment

We believe that even this simple assessment reveals a great deal about the field of urban studies. The most significant item is the divergence in content, especially with regard to the applied sci-ences on the one hand, and the explicitly urban studies journals on the other.

As noted, the applied sciences have an emphasis upon what we might broadly think of as environmental research. This is not in any sense surprising, but what is astonishing is the absence of these terms from the higher rankings of the other two columns. Our study demonstrates a virtual silence on these topics in the so-cial science literature, even after a decade of public discussion about climate change. The same is true of—and this is perhaps even more surprising—sustainability. We should expect the latter to be a field where applied science and social science reinforce each other, but that seems not to be occurring.

There is also a significant divergence with respect to methods. Geographic Information Systems (GISs) appear only in the applied sciences. We can also see differences with regard to scale. Social science research on cities pays attention to the neighborhood, which is where research on housing, public goods and crime is done. In contrast, applied science research can be thought of as scale-free, meaning that it is usually done at the metropolitan level or any sub-national scale for which data are available.

Table 1

Data on urban publications in the three different clusters.Source: Scopus, February 2012.

Journals Number of reviews and articles Keywords

Urban studies cluster 590 5109

Social sciences 3719 32121

Sciences 2429 57629

1 For simplicity, we simply ignored journals publishing chemistry, medicine and so

Table 2

Most frequent appearances of keywords in the three clusters: those in red are unique, those in blue are common to all three columns, and those shaded are discussed below. Based on data taken from Scopus, February 2012.

Fig. 2.Word cloud for social sciences, articles from 2008 and 2009, citations in 2010.

Explanations and origins

Accounting for these differences fully would require a book-length statement. We can though touch on a couple of topics here. One is the way in which urban journals have evolved; the second relates to national origins.

The content of urban journals has clear clusters: Liu has sug-gested one way to make sense of these (2005). Another interpreta-tion would be to emphasize that the field is still highly fragmented. To take the case of the US, we can see that the journals that are most visible (such as theJournal of Urban AffairsandUrban Affairs Review) have been closely connected with political science and public administration. One way that this then manifests itself is in terms of a lack of historical research (Harris & Smith, 2011).

We can see therefore that the field is still emergent—to use the heuristic terminology developed by Ramadier, we could suggest that urban studies is still moving from a disciplinary to a multidis-ciplinary focus; ahead of it lies a truly interdismultidis-ciplinary era, and then in turn it could emerge as a transdisciplinary field in its own right (Ramadier, 2004): seeFig. 4. Ramadier uses the follow-ing example, but then demonstrates the inherent challenges by

choosing only the social and behavioral sciences and erasing the humanities, the physical and the environmental sciences: ‘‘an ur-ban planner attributes the legibility of a city to its physical charac-teristics, a sociologist will attribute it to the different meanings tied to the experience of individuals in the city, and a psychologist will pay attention to the behavior of individuals in space’’ ( Rama-dier, 2004, p. 434).

In short then, fragmentation in urban studies may be a function of its evolutionary development—a point we will return to again in the Conclusion. A second factor is also important, and that connects to national origins. Bibliometric studies indicate that the global marketplace of ideas, albeit published in English, is still dominated by Western authors, who are much more likely to cite each other. Asian, Latin American and African authors remain under-cited (see for exampleBornmann & Leydesdorff, 2011).

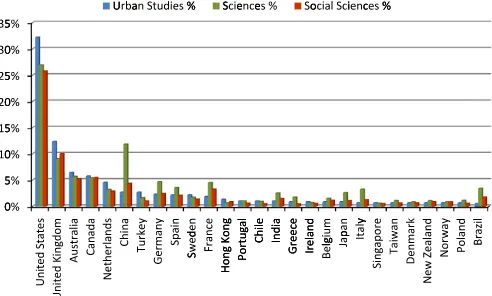

In the study reported here, there is a clear distinction between the publications in the applied sciences and those in the other two columns, with a much higher proportion of the former coming from China, and a higher proportion of the latter emanat-ing from Western scholars. We can display these differences in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.The most prolific countries for ‘urban’ research, contrasting urban studies, social sciences and applied sciences.Source: Scopus Fig. 4.the progression of disciplinary to transdisciplinary research: adapted from Ramadier.

InFig. 5, we show for the most prolific countries the percentage of papers within a category that have at least one author with an affiliation in this country. For instance, the blue2column for the

US shows that 33% of all urban studies papers have an author with an American affiliation. It shows a completely different pattern for China than for prolific countries such as the United States and United Kingdom. China publishes a remarkable percentage of all applied sci-ences papers in this subject area, and a relatively small amount of urban studies or social science papers in the same area. European countries such as Spain, Germany, France, and Italy show a similar pattern, albeit less obviously. We also see this in Brazil, Japan, and India.

For urban studies, there are a few prolific countries and many countries with lower numbers of output. For urban research in the social sciences or the sciences, the difference between the countries is smaller.

There are important processes at work here that count for these differences. In the West, a model of science has emphasized the domination of nature and this has only relatively recently been challenged. In consequence, urban research in general, and work on planning in particular, has neglected the environmental con-text: the small number of papers discussing adaption to climate change would be an example of this. In contrast, Chinese authors have been, until quite recently, constrained in the topics that they can study and on which they can publish. It is therefore unsurpris-ing that they have not focused on urban inequalities, but have turned to resource conditions.

Discussion and further research

This example began life as a thought experiment that asked if there are distinct arenas of urban thought, not merely within the urban cluster of journals, but beyond? This paper demonstrates, we believe, that such clusters do indeed exist.

On one level, a level of specialization is unremarkable—indeed, the academy is moving towards greater specificity in terms of jour-nals and the researchers who publish there. But this is also trouble-some insofar as it promotes duplication on the one hand, and talking past one another on the other. Stephanie Pincetl offers an excellent example of how this occurs in her discussion of urban ecology, elsewhere in this issue (Pincetl, in press).

The purpose of placing this example in print is also to illuminate one of the key goals of this journal, namely to promote conversa-tions between these urban clusters. Some scientific research might benefit from thinking about the city at scales such as the

neighbor-hood; conversely, more explicitly urban work must engage with environmental issues and, explicitly, the development of the liter-ature on sustainability, resilience and adaptation.

Conclusions

Bibliometric research can provide useful insights into the struc-ture and characteristics of a specific subject field. However, there will always be a need to contrast these findings with expert opin-ions, to ensure meaningful interpretation. We believe that our col-laboration, coming from very different traditions, provides a useful example of this principle.

It is our intention to extend the research that we have started here, looking at specific components of the sprawling urban litera-ture. We do this, in part, as an example of what bibliometrics can accomplish; but we are also mindful that urban studies is an important—and evolving—field. It is a cliché that ours is an urban-izing planet, and that many policy challenges reside in urban areas. Consequently, anything that can be done to make this a truly inter-disciplinary field is a valuable addition to its practice. We hope to have these follow-up studies in the journal in upcoming issues.

References

Bollen, J., Van de Sompel, H., Hagberg, A., Bettencourt, L., Chute, R., Rodriguez, M. A., & Balakireva, L. (2009). Clickstream data yields high-resolution maps of science. PLoS ONE, 4(3), e4803.http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004803.

Bornmann, L., & Leydesdorff, L. (2011). ‘Which cities produce worldwide excellent papers more than expected? A new mapping approach—Using Google maps— Based on statistical significance testing’. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(10), 1954–1962.

Broughton, V. (2006).Essential thesaurus construction. London: Facet.

Campanella, T. J. (2011).Jane Jacobs and the death and life of American planning. Design observer: Places(April). <http://places.designobserver.com/feature/jane-jacobs-and-the-death-and-life-of-american-planning/25188/>.

Harris, R., & Smith, M. E. (2011). The history in urban studies: A comment.Journal of Urban Affairs, 33(1), 99–105. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2010.00547.

Liu, Z. (2005). Visualizing the intellectual structure in urban studies: A journal co-citation analysis.Scientometrics, 62(3), 385–402.

Pincetl, S. (2012). Nature, urban development and sustainability—What new elements are needed for a more comprehensive understanding?. Cities, 29(Suppl.2), S32–S37.

Ramadier, T. (2004). Transdisciplinarity and its challenges: The case of urban studies.Futures, 36, 423–439.

Smolin, L. (2006).The trouble with physics. NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Wang, H., He, Q., Liu, X., Zhuang, Y., & Hong, S. (2012). Review: Global urbanization

research from 1991 to 2009: A systematic research review.Landscape and Urban Planning, 104, 299–309.

2 For interpretation of color in Figs. 1–3 and 5, the reader is referred to the web