CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT

Series Editors: William A. Pasmore,

Abraham B. (Rami) Shani and

Richard W. Woodman

Previous Volumes:

Volumes 1–18:

Research in Organizational Change and

RESEARCH IN

ORGANIZATIONAL

CHANGE AND

DEVELOPMENT

EDITED BY

ABRAHAM B. (RAMI) SHANI

California Polytechnic State University, USA

and Politechnico di Milano, Italy

RICHARD W. WOODMAN

Texas A&M University, USA

WILLIAM A. PASMORE

Teachers College, Columbia University, USA

First edition 2011

Copyrightr2011 Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Reprints and permission service

Contact:booksandseries@emeraldinsight.com

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying issued in the UK by The Copyright Licensing Agency and in the USA by The Copyright Clearance Center. No responsibility is accepted for the accuracy of information contained in the text, illustrations or advertisements. The opinions expressed in these chapters are not necessarily those of the Editor or the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-78052-022-3 ISSN: 0897-3016 (Series)

Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Howard House, Environmental Management System has been certified by ISOQAR to ISO 14001:2004 standards

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

vii

PREFACE

ix

DEVELOPING AN EFFECTIVE ORGANIZATION:

INTERVENTION METHOD, EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE,

AND THEORY

Michael Beer

1

STRATEGIC CHANGE AND THE JAZZ MINDSET:

EXPLORING PRACTICES THAT ENHANCE

DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES FOR ORGANIZATIONAL

IMPROVISATION

Ethan S. Bernstein and Frank J. Barrett

55

COMMUNICATION FOR CHANGE: TRANSACTIVE

MEMORY SYSTEMS AS DYNAMIC CAPABILITIES

Luis Felipe Go´mez and Dawna I. Ballard

91

DEVELOPING AND SUSTAINING CHANGE

CAPABILITY VIA LEARNING MECHANISMS:

A LONGITUDINAL PERSPECTIVE ON

TRANSFORMATION

Tobias Fredberg, Flemming Norrgren and

Abraham B. (Rami) Shani

117

MAPPING MOMENTUM FLUCTUATIONS DURING

ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE: A MULTISTUDY

VALIDATION

Karen J. Jansen and David A. Hofmann

163

TOWARD A DYNAMIC DESCRIPTION OF THE

ATTRIBUTES OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

Guido Maes and Geert Van Hootegem

191

REVISITING SOCIAL SPACE: RELATIONAL

THINKING ABOUT ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

Victor J. Friedman

233

TIPPING THE BALANCE: OVERCOMING

PERSISTENT PROBLEMS IN ORGANIZATIONAL

CHANGE

William A. Pasmore

259

Dawna I. Ballard

Department of Communication

Studies, University of Texas at Austin,

Austin, TX, USA

Frank J. Barrett

Graduate School of Business and

Public Policy, Naval Postgraduate

School, Monterey, CA, USA

Michael Beer

Harvard Business School, Boston,

MA, USA; TruePoint, USA

Ethan S. Bernstein

Harvard Business School, Boston,

MA, USA

Tobias Fredberg

Department of Technology

Management and Economics, Chalmers

University of Technology, Gothenburg,

Sweden; Truepoint, USA

Victor J. Friedman

Department of Sociology and

Anthropology/Department of

Behavioral Sciences, Max Stern

College of Yezreel Valley, Yezreel

Valley, Israel

Luis Felipe Go´mez

Department of Communication

Studies, Texas State University,

San Marcos, TX, USA

David A. Hofmann

Department of Management,

University of North Carolina,

Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Karen J. Jansen

Department of Organizational

Behavior and Strategy, University

of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Guido Maes

Center for Sociological Research,

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven,

Leuven, Belgium

Flemming Norrgren

Department of Technology

Management and Economics,

Chalmers University of Technology,

Gothenburg, Sweden; TruePoint, USA

William A. Pasmore

Teachers College, Columbia

University, New York, NY, USA

Abraham B. (Rami) Shani

Orfalea College of Business, California

Polytechnic State University, San Luis

Obispo, CA, USA; Department of

Management, Economics and

Industrial Engineering, Politecnico di

Milano, Milan, Italy

Volume 19 ofResearch in Organizational Change and Developmentincludes chapters by an internationally diverse set of authors including Michael Beer, Victor J. Friedman, Luis Felipe Go´mez and Dawna I. Ballard, Ethan S. Bernstein and Frank J. Barrett, Karen J. Jansen and David A. Hofmann, Guido Maes and Geert Van Hootegem, Tobias Fredberg, Flemming Norrgren and Abraham B. (Rami) Shani, and William A. Pasmore. The ideas expressed by these authors are as diverse as their backgrounds.

New methodologies are introduced, such as the strategic fitness process developed by Michael Beer and his colleagues for engaging leaders in better understanding the reactions of employees to strategic change efforts. Beer helps us to understand that leaders often operate on incomplete or incorrect information about how their admonitions to change are received because people fear speaking to power. The strategic fitness process overcomes this dynamic by creating a safe space in which handpicked members of an interview team share the results of their findings in a fishbowl that senior leaders observe. With careful facilitation, according to Beer, real break-throughs can be achieved in aligning leaders and their followers.

For some time now, we have recognized that jazz provides a powerful metaphor for organizational improvisation. Bernstein and Barrett take us beyond the obvious similarities to understand the fundamental principles that guide jazz musicians as they play. Parallels to organization change work are clear and compelling.

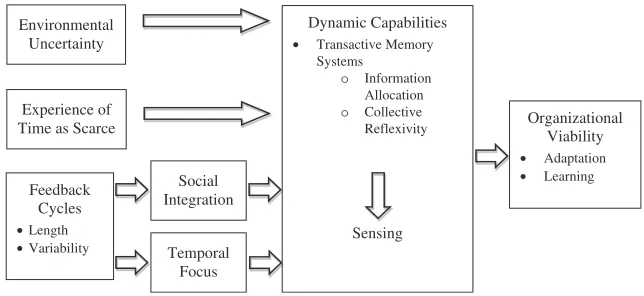

Go´mez and Ballard discuss the importance of transactive memory systems to long-term organizational viability. Since organization environ-ments are dynamic, choices must be made about how to allocate resources to respond to threats and opportunities. Transactive memory systems are the built-in processes that guide these decisions. Understanding how they function and what can be done to influence their operation is key to invoking and sustaining change.

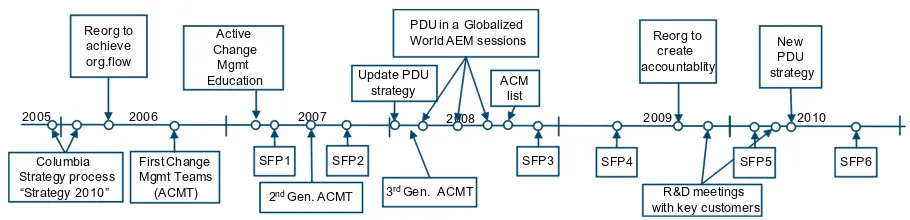

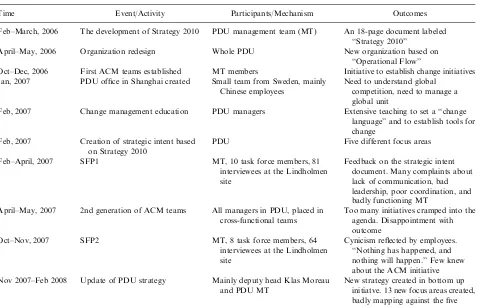

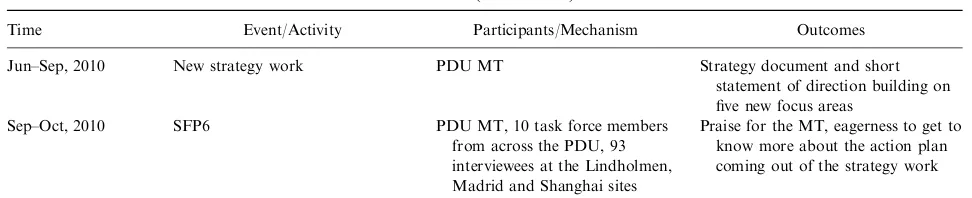

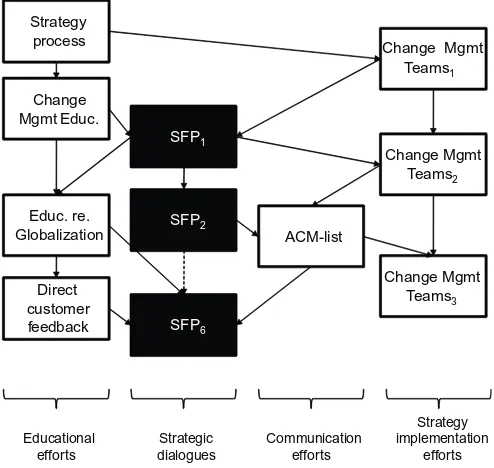

Along similar lines, Fredberg, Norrgren, and Shani review the results of a five-year study at Ericsson on the nature and use of learning mecha-nisms to support change. While it seems obvious that most change efforts involve learning, few change agents are explicit in their attempt to construct

forums in and through which organizational members can reflect on their experiences, engage in joint sensemaking, and apply hypotheses to future opportunities. Fredberg, Norrgren, and Shani embellish upon the idea of parallel structures that facilitate change in this informative paper about a long-term change effort.

Jansen and Hofmann illustrate how to map the flows of momentum during change efforts using two studies: one in the laboratory and another in an actual organization. By paying attention to when these shifts in momentum occur and why, we can learn much more about the obstacles to commitment during change and what is required to sustain ongoing support.

Maes and Van Hootegem reviewed hundreds of studies of change to understand the different dimensions that can be used to describe change. Usually, change is described in a dichotomous fashion, for example, incremental versus transformational. After their review, Maes and Van Hootegem classify change using eight different dimensions, including control, scope, frequency, stride, time, tempo, goal, and style. Each of these eight dimensions is a continuum unto itself, and the dimensions can be combined together to lend tremendous specificity and richness to how we talk about change.

Friedman digs deep into the early work of Lewin to explore his concept of social space and its implications for change efforts. Lewin wasn’t crystal clear in describing what he meant by the term ‘‘social space.’’ To clarify the concept, Friedman consults the work of authors Ernst Cassirer and Pierre Bourdieu to learn how they may have influenced Lewin’s thinking and what exactly the critical implications for change efforts could be.

Finally, Pasmore notes that the current high failure rate of change efforts is a cause for alarm and that more careful attention to the causes of failures could help to tip the balance in favor of success. He explores threats to success associated with four phases of change efforts and offers potential solutions.

Volume 19, we ask you to consider your own contributions to our field and to contact us to suggest topics for future volumes. We will be excited to hear from you, and to learn about the new directions you propose for our profession.

Abraham B. (Rami) Shani Richard W. Woodman William A. Pasmore

ORGANIZATION: INTERVENTION

METHOD, EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE,

AND THEORY

Michael Beer

ABSTRACT

The field of organization development is fragmented and lacks a coherent and integrated theory and method for developing an effective organization. A 20-year action research program led to the development and evaluation of the Strategic Fitness Process (SFP) – a platform by which senior leaders, with the help of consultants, can have an honest, collective, and public conversation about their organization’s alignment with espoused strategy and values. The research has identified a syndrome of six silent barriers to effectiveness and a dynamic theory of organizational effectiveness. Empirical evidence from the 20-year study demonstrates that SFP always enables truth to speak to power safely, and in a majority of cases enables senior teams to transform silent barriers into strengths, realign their organization’s design and strategic management process with strategy and values, and in a few cases employ SFP as an ongoing learning and governance process. Implications for organization and leadership develop-ment and corporate governance are discussed.

Research in Organizational Change and Development, Volume 19, 1–54 Copyrightr2011 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved

Science is about describing how the universe works. Engineering is about creating something that works.

– Neil Armstrong, Astronaut1

‘‘We have great strategy but we cannot implement it. Can you help us become a company capable of implementing strategy?’’ This is the paraphrase of the challenge presented to me in 1990 by the CEO and Vice President of Strategy and Human Resources of Becton Dickinson (BD), a global medical technology company.

This challenge led to the development of the Strategic Fitness Process (SFP) by Russell Eisenstat and me. It began with the assumption that organization change and development begins with conversations, an assumption that has since been validated by a burgeoning practice and literature on organizational discourse and its role in organizational development (Oswick, Grant, Marshak, & Cox, 2010;Marshak & Grant, 2008;Bushe & Marshak, 2009). Indeed, the problem is that conversations are not always effective. The right people are not involved to ensure engagement and commitment, the right things are not discussed, and the conversations are not open and honest (Argyris, 1985). Consequently, relevant strategic, leadership, organization design, decision rights, and cultural issues remain undiscussable and cannot be addressed. This slows or blocks change. When unintended consequences of change emerge, they too are undiscussable. Cynicism increases, commitment declines, and momentum is lost.

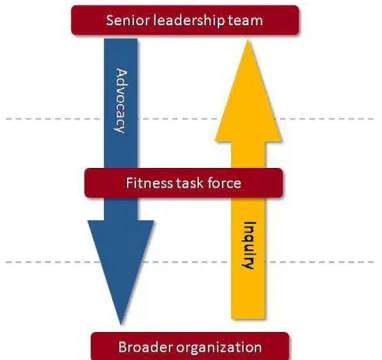

It is these dynamics that led us to develop a structured process by which a senior team can foster what we have come to call anhonest, collective, and public conversation (involving a large circle of organizational members) about organizational and leadership effectiveness (Beer, 2009; Beer & Eisenstat, 1996, 2004). It is a platform by which managers, consultants and organizational members can collaborate in an inquirythat enables them to learn jointly about the effectiveness of the organization – its alignment with espoused strategy and values. Because SFP breaks organizational silence and reveals valid data – the truth – about the organization to consultants and leaders, it may be thought of as a collaborative research method that enables insights and theory development while at the same time developing commitment to change (Shani, Morhman, Pasmore, Stymne, & Adler, 2008;

Adler & Beer, 2008;Van de Van, 2007;Beer, 2001).

country organizations of global firms, and operating units such as manufacturing plants, hospitals, and restaurants in a retail chain. While in most cases the organizations were for profit businesses, SFP has also been applied in not for profit organizations.

Twenty years of applying the same inquiry method in a diverse set of organizations offers a unique opportunity to learn about barriers to organizational effectiveness and performance and an opportunity to collect data about the efficacy of SFP across many different organizations. This chapter will discusses:

The action research program

Theory and assumptions that informed the development of SFP The SFP

An emergent theory of organizational effectiveness Empirical research findings about the efficacy of SFP

Emergent theory and principles for developing an effective organization Implications for practice

An organization is effective when its leaders are able to realign organiza-tional design, culture, and people (capabilities and commitment) with continuous changes in the competitive and social environment. The problem of organizational alignment, adaption, and learning, which SFP is intended to facilitate, has been a central concern of economists and organizational theorists. Population ecologists and economists have taken the view that all corporations go through a life cycle of birth, development, and ultimate destruction (Hannan & Freeman, 1975). The market is seen as the ultimate arbiter of effectiveness and survival. Essentially, markets ensure organiza-tional effectiveness through the process of ‘‘creative destruction’’ (Schumpeter, 1942; Foster & Kaplan, 2001). Most organizations ultimately destruct because the configuration of management practices developed in periods of success proves difficult to change in response to environmental change (Miller, 1990a).

These data suggest that the process of developing and sustaining effectiveness is extremely challenging. In a study by Collins of 1,435 companies between 1965 and 1995, only 11 were able to move from simply good performance to great performance, defined as the cumulative stock returns of 6.9 times returns for the general market for a period of 15 years or more, and this after a concerted effort to transform them (Collins, 2002). Since the completion of the, study the performance of approximately half of these companies has declined below the level that qualified them as great companies. The finding that CEO tenure has declined since the early 1990s from 10 years to less than 4 years further suggests that leading a company for sustained success in a rapidly changing environment is extremely difficult and is achieved by only a relatively small number of organizations.

From the perspective of senior management, however, leading realign-ment and continuous change is essential, regardless of how difficult it may be. Robert Bauman, former CEO of SmithKlein Beecham and an experienced change leader, captured the importance of the capacity for learning and change as the key to competitive advantage when he noted: ‘‘Most important in implementing change in the near term is instilling the capacity for change in the long term. In my view the capacity for ongoing change is the ultimate source of competitive advantage’’ (Bauman, 1998). Academics have framed the challenge as an organizational learning one (Argyris & Schon, 1996;Senge, 1990). Creating adaptive organizations has been a subject of considerable academic discourse (Lawler & Worley, 2006, 2011;Tushman & O’Reilly, 2002;Beer, 2009).

THE ACTION RESEARCH PROGRAM

As noted earlier, SFP was designed to meet the difficulties BD was experiencing in implementing its corporate and business unit strategies (Beer & Williamson, 1991). Virtually all of the company’s senior executives, including its CEO, had been strategy consultants in some of the largest and best known management consulting firms before joining the firm. As a strategy consultant 20 years earlier, BD’s CEO introduced ‘‘Strategic Profiling’’ (SP). SP was a structured processes by which senior teams, with the help of a trained facilitator, discuss and answer questions embedded in Michael Porter’s strategic framework (Porter, 1985) and develop their strategy as opposed to more traditional expert consultant models. It is therefore consistent with a broad stream of research on collaborative research and learning (Docherty & Shani, 2008).

When I was approached about the strategy implementation problem in 1988, SP was institutionalized in the company – a manual existed and line managers around the company had been trained as facilitators. Thus, the stage was set conceptually for the invention of SFP, a parallel process intended to follow SP. We learned later that the cultural underpinnings for honest conversations about difficult organizational issues did not exist at BD, and the process had to be robust enough to enable these conversations. Between 1988 and 1995 Russ Eisenstat and I, in collaboration with the Vice President of Human Resources (HR) and his successor, developed SFP and piloted it in three business units. Subsequently, SFP was implemented at the corporate level, in numerous other business units, functional organiza-tions such as quality and human resources, country organizaorganiza-tions, and one manufacturing plant. Despite stories about painful feedback in two pilots and resultant resistance, reports of success in a business unit, led by a highly respected and highly potential general manager who became the company’s CEO in 2000, caused senior management to commit to SFP. A manual to guide and train internal resources was written, and internal HR and Strategy professionals were apprenticed to facilitate SFP.

As academics with scholar–practitioners orientation, our goal was not just to develop an intervention method but research it and learn about the problem of developing an aligned and effective organization. This chapter summarizes findings and conclusions drawn from several forms of inquiry described later. Given the 20-year period of time, it is important for the reader to understand that assumptions that we started with, the SFP intervention method itself, and the findings and conclusions I discuss in this chapter have evolved over time through the iterative process of intervention, research, reflection, and further action. The reader may wonder how objective the findings and conclusions reported here are, given that consultants were also researchers. The following aspects of our journey should be considered in answering this question:

We spent time reflecting on and analyzing more and less successful

applications of SFP.

A large number of cases about organizations that underwent SFP were

written by independent researchers. These allowed us to conduct a rigorous post hoc analysis of 12 applications of SFP discussed later.

A 20-year period of time enabled us to evaluate and revaluate what we

were learning.

A good many assumptions about the active ingredients in the SFP process

have changed over the years.

ASSUMPTIONS AND THEORY UNDERLYING SFP

How could we help BD improve its effectiveness in executing strategy and adapting to changing circumstances? We brought to this question several assumptions, rooted in research and theory as well as my experience as an internal organization development (OD) consultant at Corning Glass Works. Acting as social engineers we crafted SFP to reflect our assumptions and used experience over time to reformulate our assumption and reengineer the process.

and its chosen strategy (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967, 1969; Miles & Snow, 1978;Miller, 1986, 1987, 1990a; Labovitz, 1997). Initially, we chose the 7S framework developed by McKinsey as the analytic map senior teams could use to diagnose alignment and later developed our own model (Pascale & Athos, 1981). Consistent with contingency theory, we assumed that the configuration of the organization, its pattern of alignment, would differ depending on the business strategy (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967; Miles & Snow, 1978;Miller, 1986). We also assumed that the problem of alignment is continuous and therefore organizational learning has to be continuous. My OD practice and research at Corning Glass Works in the late 1960s and early 1970s had demonstrated that a planned redesign process that follows these assumptions could dramatically improve effectiveness and perfor-mance (Beer, 1976).

A second corollary assumption, one that has been reinforced after many applications of SFP, is that seeing the whole system – all facets of the organization and its environment – is essential for total systems change (Oshry, 2007). Managers too often make attributions of causality for problems they face to one presenting symptom – ineffective people, business conditions, or technical problems, for example – and fail to see the multiple factors in interaction. Failing to see the system prevents change in systems. It leads to the fallacy of programmatic change initiatives aimed at one facet of the organization, typically education or training, to enhance knowledge or change attitudes (Beer, Eisenstat, & Spector, 1990). These programs are often simple and easy fixes that protect managers from learning about deeper and more systemic problems including their own leadership. We designed SFP to avoid these simple fixes to complex organizational effectiveness problems.

developed (Argyris & Schon, 1996; Senge, 2006). We concluded that teaching managers dialogue skills in concurrent advocacy and inquiry (Argyris, 1990b), while essential in the long run, would take years. We had to find a way to break the silence and motivate an honest conversation that did not depend on deep changes in skills and culture.Beckhard (1976)had demonstrated that a structured process for surfacing difficult issues could work. We purposely eschewed surveys as means of data collection because they limit what is learned to known problems and do not reveal complexity and interaction between multiple facets of the system.

A fifth set of assumption underlying the design of SFP is that the process consultation model is the best way to help managers cope with the challenges they face (Schein, 1999). These assumptions are:

The client does not fully understand the root causes of their problems and

need help in diagnosis and action taking.

Beyond a solution to the problem, clients should be left with a capability

to learn the truth about their organization, diagnose problems, and take action in the future.

Only the client knows what will work and not work in their organization.

Using expert knowledge based on research as well as practical experience, the consultant can present alternatives, but it is the client who must make choices.

In effect, SFP is a process by which senior teams can self-design their organizations with the help from a scholar–practitioner (Cummings & Mohrman, 1989). The challenges of this role will become apparent in the discussion that follows and have been discussed extensively in a 2009 issue of theJournal of Applied Behavioral Science(Vol. 45, No. 1).

A sixth corollary assumption is that participation, consultation, and engagement by as wide a group of employees as practical enhances the quality of diagnosis, solutions, and commitment. It develops community and participant capabilities, in effect changing mutual expectations and culture (Vroom & Yetton, 1973; Macy, Schneider, Barbera, & Young, 2009). For these reasons we chose a task force of employees to research the organization. Participation, it was assumed, would also develop those involved in the process (Vroom & Jago, 1988).

greater effectiveness while developing commitment to act on findings (Van de Van, 2007).

Eighth, we assumed that developing an effective corporation require changes at multiple levels and units – functional units, operating units, and geographic entities, for example (Beer et al., 1990). SFP at the top is a tool for redesigning the larger organizational context and the role of the top team, but we thought of SFP as a leadership platform for developing organizational effectiveness in the corporation’s multiple subunits. Over time, we came to see it as a process for improving the quality of leadership and management throughout a company’s multiple units.

THE SFP PROCESS

The design of the SFP process was based on the assumptions outlined above. It is a multilevel process that involves the senior team, a task force of approximately eight employees, one to two levels below the senior team and approximately 100 key people inside and a fewer number outside the organization (customers, suppliers, partners, and other key constituencies as appropriate). They are interviewed about organizational strengths and barriers to achieving the organization’s strategic intent. We have found that 100 interviews are sufficient to offer a comprehensive picture of the organization regardless of its size. Interviews are at the top three levels or so, given the strategic nature of the inquiry.

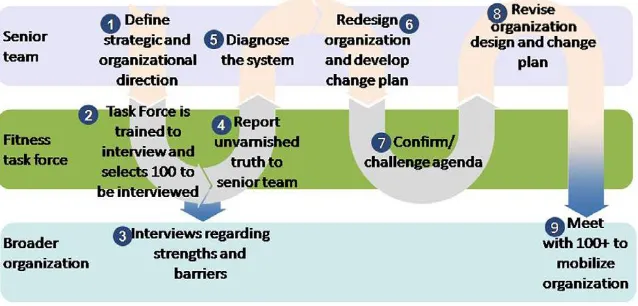

The archetypical process has nine steps depicted inFig. 1. As mentioned earlier, the process can and has been applied at multiple organizational levels, but always with the leader and the senior team at the center of the process. Contracting with the general manager or CEO is framed in performance and values terms. What is the performance gap he/she is trying to close? What is the strategy that the business needs to execute in order to close the performance gap? What are the values by which leaders would like to govern the organization?

SFP and the senior team’s plans to communicate what they heard, their diagnosis, and action plans to the whole organization.

The first step in the process is a one-day senior team meeting to develop a statement of organizational direction – performance goals, strategy, and values. A two-page statement is drafted and becomes the basis of the inquiry. At that meeting the senior team commissions a task force of eight of their best people who will conduct the inquiry. These must be the best people, and ones who will be believed when they return with their feedback. The task force is prepared to conduct the inquiry in a one-day training session led by consultants. The general manager/CEO starts the day by explaining the statement of direction and asking for unvarnished feedback about barriers to execution. The task force is then trained to conduct interviews. They, not the senior team, select the people they will interview. They interview outside of their function, business, or geography. Consultants, not the task force, interview the senior team.

When interviews are completed – usually in three weeks – the task force meets for a day to analyze their interviews and identify themes – strengths and barriers – and give their feedback to the senior team. As I will show below, these themes are potentially threatening because they are about the efficacy of the organization and their leadership team.

Task force feedback, diagnosis by the senior team, and plans for changing the system occur in a three-day Fitness Meeting – the main catalytic SFP event. To enable truth to speak to power, a fishbowl method is employed (Fig. 2). Task force members discuss their findings and provide examples

from interviews, while the senior team, guided by ground rules, listens nondefensively. Diagnosis and action planning occur on the second and third day without the task force.

Having developed an action plan, the senior team meets with the task force to tell them what they heard, their diagnosis, and their action plan. Task force members meet alone to discuss the quality of the action plan and its implementability. They then meet with the senior team to offer their critique of the plan. As I will show later, this is a very important step in the process.

To mobilize the organization for change, a meeting with the 100 employees who were interviewed plus other key employees takes place. The senior team, ideally with participation of the task force, communicates what they heard from the task force, their diagnosis, and action plan for change. Participants are then engaged in further discussion and feedback to the senior team.

The elapsed time for the process is typically six to eight weeks. Consultants – external and/or internal – play two roles. They facilitate the process, ensuring that it retains essential conditions for success and act as subject matter resources in diagnostic and change planning discussions. An appendix at the end of this chapter provides more detail about each SFP step. An SFP manual provides details about the total process from beginning to end (Eisenstat & Beer, 1998).

SFP is a powerful episode. OD is a process that takes years. Senior teams are urged to meet with the task force periodically to discuss progress in the

transformation and to institutionalize SFP as a regular learning and governance process. If they have been able to establish a helping relationship with the senior team, consultants become thought partners to the leader and senior team throughout the transformation – a period that can be as long as several years. If SFP is recycled periodically, the three-day Fitness Meeting offers a perfect opportunity to collaborate with senior team in assessing progress and discussing further interventions. Having developed internal capability to orchestrate the SFP process, the senior team of one business unit asked its consultant to come every year to participate in the three-day Fitness Meeting to hear from the task force and participate in the development of a response.

Honest collective conversations about the system as a whole are powerful ways to begin the process of OD. Beyond the development fostered by participation in the process, and this can be substantial, deeper development of organizational, team, or individual capabilities is typically needed. This is something that may require further intervention and learning. A variety of learning mechanisms and interventions will have to be designed to enable this deeper learning in particular organizational domains that the senior team has targeted for change (Beer, 1980;Shani & Docherty, 2003; Docherty & Shani, 2008). A chapter in this volume by Fredberg, Norrgren, and Shani (2011)illustrates how cognitive, structural, and procedural learning mechan-isms designed into SFP and following it were employed to build organiza-tional capabilities. Our experience suggests that there is variability in how much help senior teams require to do this work.

Each application of SFP has varied somewhat depending on the situation and the consultant, but the essential features of honest, collective, and public conversations intended to realign the organization with the leadership team’s espoused direction have been constant.

AN EMERGENT THEORY OF ORGANIZATIONAL

EFFECTIVENESS

original analysis (Beer & Eisenstat, 2000). Analysis of a written case about an underperforming and low-commitment business unit at Corning Glass Works, written a decade and a half before the current action research program began, confirmed that the same barriers existed there and that they explained quite well underperformance and low commitment in that business (Beer, 1976).

Because we were consultants who were directly involved in helping these organizations, we were able to make sense of how the barriers reported below interacted to undermine organizational effectiveness. And because we could follow-up and learn how the organization had changed as a result of SFP, we were able to learn if SFP had materially affected the barriers. This allowed us to form a dynamic theory of organizational effectiveness and development.

We have called the barriers silent killers because like hypertension and cholesterol in humans the six barriers cause severe damage to an organization and are ‘‘unknown’’ to the senior team and the organization at large (Beer & Eisenstat, 2000). By unknown I mean that the barriers, though known to most key people in the organization and to senior management, they were undiscussable and therefore were not subject to action, a point also made byMarshak (2006).

It is important to note that in most instances task forces reported that people in the organization – their dedication and commitment – were perceived as a strength. While these organizations had some under-performing people, the message was that the organizational context defined by the six barriers discussed below was the first-order cause of ineffective-ness, undermining the capabilities and motivation employees brought to their work. This finding echoes Deming’s findings that the system, not the people, are the cause of ineffectiveness and poor quality (Deming, 1986).

The Silent Killers: Syndrome of Barriers to Effectiveness

While task forces found a variety of ways to describe what stood in the way of greater effectiveness, our content analysis identified the following six barriers:

1. Unclear strategy, values, and conflicting priorities 2. An ineffective senior team

4. Poor coordination and communication across functions, business, or geographic entities

5. Inadequate leadership development and leadership resources below the top

6. Poor vertical communication – down and up

These barriers should not be surprising to anyone who has worked in organizations or consulted them. When I have presented them to manage-ment audiences, they are immediately recognized by many as present in their own organization.

Considerable research has identified the six barriers as problems in organizations. For example, Hambrick has identified the pervasiveness of ineffective senior teams and their effects (Hambrick, 1998). Wageman and her associates have shown that a vast majority of senior teams they studied were perceived to be ineffective, and they cite a variety of factors (Wageman, Nunes, Burruss, & Hackman, 2008). For example, senior team members vary widely in their understanding of who is or is not on the senior team as well as the purpose and role of the senior team. Eisenhardt has shown that top team effectiveness is related to organizational performance (Eisenhardt & Schoonhoven, 1990). Others have shown that coordination and collaboration across differentiated functions and activities as well as cultural characteristics such as conflict resolution modes are critical in uncertain environments (Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). The importance of downward communication in leading change has been widely acknowledged (Kotter, 1996). And hierarchy and defensive routines have been documented and shown to reduce voice and the capacity of honest and open–fact based problem solving (Argyris, 1985, 1990; Detert & Edmondson, 2007). OD practice has targeted some of these barriers for intervention. Team building and intergroup interventions, for example, have been standard interventions methods since the 1960s and 1970s (Beer, 1980).

Our findings not only confirm previous research but also provide insights into the relationship between these six silent barriers and how they under-mine organizational effectiveness. Because these barriers typically existed together in the organizations we studied, we came to see them as a syndrome of mutually reinforcing and self-sealing (Beer & Eisenstat, 2000). In all the organizations we studied, the silent killers blocked three fundamental organizational capabilities essential for organizational effec-tiveness. These are:

2. The capacity to execute the direction

3. The capacity of the organization to learn from enacting: a. That the strategy needs modification and/or

b. The organization’s design and culture require change

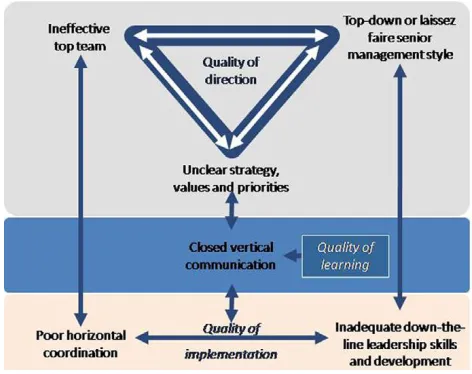

Fig. 3illustrates how the barriers interact to erode these three capabilities. The first three barriers, an ineffective senior team, top-down or laissez fair leadership, and unclear organizational direction and conflicting priorities, mutually reinforce each other. They prevent senior teams from developing a high-quality direction. An ineffective senior team cannot have the dialogue necessary to create a high-quality direction, and the lack of a common direction prevents the group from working together effectively. The group may be ineffective because of the leaders top-down or laissez faire style or that style may be the leader’s response to an ineffective team. He/she stops trying to work through the team.

Poor execution of the senior team’s direction, according to task forces, is a function of poor coordination and the paucity of down the line leaders available to lead strategic initiatives. These barriers are a direct result of an ineffective senior team and poor downward communication. Ineffective teams are often beset by power struggles and do not share common values. Such teams find it difficult to confront changes in organization

design – roles, responsibilities, relationships, and decision rights – needed to improve integration. Ineffectiveness also makes it difficult for teams to define a common set of values, making it in turn impossible to develop a collaborative culture.

Similarly, ineffective senior teams do not share a common view about what constitutes good managerial performance and potential, making it impossible for them to agree on high-potential people and how to develop them. They are also reluctant to see people as a shared resource to be jointly evaluated and developed through assignments in different parts of the organization. ‘‘Our business unit leaders refuse requests for their best people and transfer their poorest performers,’’ reported a task force to a CEO and his senior team concerned about why the company was not developing managers. Poor downward communication undermines execution. If senior teams do not engage lower level people in a dialogue about strategy and values, understanding and commitment suffer. People in differentiated departments are less prone to work together to execute the strategy. It becomes easier for siloed departments to maintain different priorities.

Poor upward communication – the inability for people to communicate openly to senior teams – prevents lower levels from speaking up about the six barriers, thus making them self-sealing. The senior team is prevented from learning and changing their leadership role and behavior or redes-igning the organization to enable better coordination. The difficulty lower levels have speaking honestly to senior teams became clear through many applications of SFP. The first task force we worked with at BD thought they had been given a career limiting opportunity. When they completed their data collection and were preparing to give their feedback to their senior team, they were even more anxious. This level of anxiety was apparent in virtually all the organizations that were facing effectiveness problems. ‘‘Don’t shoot the messenger’’ was a common refrain that task forces communicated to senior teams before launching into their feedback. It was clear to us that had there been an honest productive dialogue between lower levels and the senior team, SFP would not have been needed. The positive changes that SFP produced, which are discussed later, illustrates the power of open upward communication in enabling realignment, though our findings suggest that this conversation must be carefully orchestrated to enable that learning.

coordination is always a challenge. When markets quake and companies confront strategic inflection points, stress points become wide fault lines. Organization design must be reconceived on a number of dimensions and new capabilities must be developed or the organization’s performance will decline. Short of replacing the general manager/CEO these changes cannot be made, our research suggests, unless leaders and their senior teams confront the six silent barriers. If they do not, it is likely they will be replaced. The importance of honest confronting conversations to the per-formance of companies is supported by the research of Lawrence and Lorsch (1967). They found that in uncertain environments, confrontation of conflict, as opposed to smoothing or avoidance, characterized high-performing firms when compared with low-high-performing firms.

The Silent Killers at Work: An Illustrative Case

We have two competing strategies that are battling each other for the same resources. The resultant factions around these two strategies are tearing the organization apart.

The members of the top team are operating within their own functional silos. They are like a group of fiefdoms that refuse to operate effectively for fear that they will lose power.

There is a cold war going on between Research and Development (R&D) and the Custom Systems department located within manufacturing.

SRSD is still not sure what kind of business it wants to be.

These quotes, taken from a report of a fitness task force at Hewlett Packard’s Santa Rosa Systems Division (SRSD), are illustrative of the ineffectiveness of this organization at the time they undertook SFP (Beer & Weber, 1997).

As the quotes suggest, six silent barriers were blocking SRSD’s effectiveness and performance. Poor coordination – the ‘‘cold war’’ – between R&D and Custom Systems, an application engineering group, was a major barrier. One reason was that two conflicting strategies – development of new technology platforms versus rapid delivery of mission critical systems using existing technology – were ‘‘tearing the organization apart.’’ They were leading to different priorities and causing daily conflicts about scarce engineering resources.

The lack of agreement about strategy and priorities was understandable, given what the task force, and we as consultants, learned about the senior team. It rarely met as a group and when it did, administrative issues were discussed, not strategy or priorities. Scott, SRSD’s general manager, preferred to meet with individuals one on one. According to the task force and senior team members, his laissez fair style – not bringing the senior team together to confront strategic issues – was rooted in his aversion to conflict.

Poor coordination was also a function of ineffective and poorly designed cross-functional business teams. Section managers from R&D appointed as their leaders werenotheld accountable for running a business profitably and lacked the general management experience and perspective to manage a business or lead cross-functional business team. For example, their R&D perspective caused them to focus on technology development in meetings and blinded them to the role Custom Systems, the applications engineering function, could play in identifying customer needs and potential new systems to fill those needs, not to speak of the revenue the Custom Systems group was providing SRSD while new technology platforms were still under development. Soon application engineers stopped coming to business team meetings and felt undervalued further fueling a growing ‘‘cold war’’ between the two engineering groups.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE OF SFP EFFECTIVENESS

Over the course of 20 years, the following forms of inquiry were employed to evaluate SFP’s effectiveness:

Harvard Business School cases were written on applications of SFP at BD

and some 10 other organizations. These cases included applications at the corporate level led by the CEO and top management team, business units, country organizations, and operating units.

A post hoc study was conducted on 10 business units at BD that had

applied SFP. Interviews and survey of SFP participants at multiple levels of each unit were conducted by an independent researcher. A content analysis of findings from 10 task forces was also conducted.

A post hoc study was conducted on extent of change resulting from an

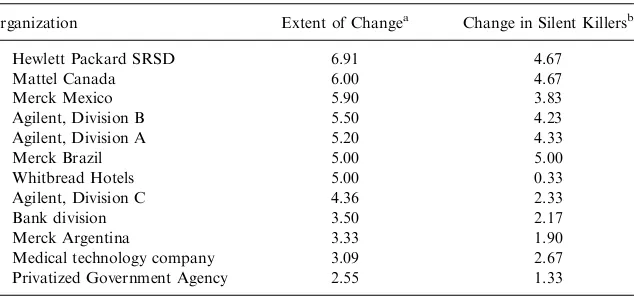

SFP intervention in 12 organizations. Cases were written by independent researchers. Researchers and consultants to the organizational units under study read the cases and inductively created a set of items in several categories – preconditions, change process, and change outcomes. These items were then rated by each member of the research team individually. The group then discussed their ratings and developed consensuses mean scores. By creating a mean of mean scores for 11 SFP outcome ratings, we were able to create a score for extent of change following SFP.2

Participant observation made by consultants who facilitated SFPs over a

20-year period was studied. This enabled insights into the organization and the attitudes and behaviors of participants in the process. These observations enable a deep clinical understanding of the method, its effects, and the conditions for success.

A deep clinical analysis was conducted on the application of SFP at HP

SRSD over a six year period. Most of the quotes are taken from the analysis if this case.

difference between pre and post hoc silent killer ratings on a seven-point scale. As I will show, our research and experience demonstrates that SFP leads to realignment in leadership roles, attitudes and behavior, organiza-tion design, strategic management, and organizaorganiza-tion behavior in a majority of cases. Below are our major conclusions.

SFP Uniformly Enables Honest, Safe Conversations

SFP enables senior teams to hear the unvarnished, sometimes threatening, truths about the quality of their strategy, leadership, and organization. There has never been a single instance where task forces have shaded the truth, though they exhibit considerable anxiety about reporting it and will try to find the most diplomatic way to do it. Nor have senior teams shut down the conversation or stopped completion of all steps in the process, despite their obvious discomfort with the findings. Based on years of experience with SFP, we conclude that the following features of the intervention, some developed as a result of early experience with the process, account for producing a constructive dialogue about threatening issues:

The senior team, working as a group, develops the statement of strategic

direction that is used as the basis of the inquiry. Thus, the focus of SFP is

Table 1. Extent of Change in 12 Organizations.

Organization Extent of Changea Change in Silent Killersb

Hewlett Packard SRSD 6.91 4.67

Mattel Canada 6.00 4.67

Merck Mexico 5.90 3.83

Agilent, Division B 5.50 4.23

Agilent, Division A 5.20 4.33

Merck Brazil 5.00 5.00

Whitbread Hotels 5.00 0.33

Agilent, Division C 4.36 2.33

Bank division 3.50 2.17

Merck Argentina 3.33 1.90

Medical technology company 3.09 2.67

Privatized Government Agency 2.55 1.33

aExtent of change scores are a mean of twelve separate organizational outcome items rated on a seven point scale post hoc.

performance and strategy, a focus that motivates the senior team to deal with disconfirming data. As one general manager noted, ‘‘Strategy is central to our success so anything we can learn that may prevent its execution is important to understand.’’

The senior team must select their best people for the task force and commit

in advance to all steps in the process. This makes it hard for them to do anything else but accept task force findings and act on them. Senior teams understand that if they reject feedback or do not respond to it, they will lose credibility and legitimacy with their key people – the task force as well as the 100 employees who were interviewed – not to speak of the larger organization, which has been informed about the inquiry and promised feedback from senior management. While there are differences in senior team’s understanding about the implication of the process for their legitimacy, this understanding is deepened by the emotional nature of the process. One general manager noted, ‘‘we did not know what we were getting into,’’ even though he and his team had been told what to expect.

Senior teams and the task force are fortified by the knowledge that a

rigorous process for collecting data and analyzing it was employed and by the fact that they selected a task force of their best people, one they can, indeed must, believe.

Consistent with Cameron & Powley’s (2008)observation that ‘‘negative

news sells more than positive news,’’ there was a natural tendency for task forces to emphasize the negative – the barriers to effectiveness. Senior teams responded negatively to this, arguing that there were many positive things about their organization that were being ignored. They sought a more balanced view. Citing several studies that find a positive climate leads to more favorable human and organizational outcomes, Bartuneck and Woodman (in press) argue for a balance. That same logic led us to ask task forces to explicitly ask a question about strengths and report them before barriers are discussed. That balance, which incidentally is hard for task forces to maintain (they spend far less time onstrengths), has made the feedback ‘‘safer’’ for senior teams.

Initially, we asked task forces to develop a PowerPoint presentation, but

found that this prevented them from presenting the full richness of their findings and that it was intimidating. That led to the fishbowl (Fig. 2). Speaking as a group and as reporters, as opposed for themselves, enables honesty not otherwise possible, though anxiety is still high, particularly the first time an organization implements SFP.

Ground rules prevent senior team defensiveness or the task force blaming the

general manager in the first SFP conducted at BD demonstrated defensive-ness by arguing with task force findings. The ground rule that senior team cannot interrupt the task force’s report and that questions of clarification only are allowed after each theme and at the end of the report prevents defensive responses that might undermine the courage of the task force. With the exception of presenting ground rules, consultants do not play an active role during the task force feedback. The design of the structure and process is sufficient to enable truth to speak to power.

Engagement in Honest Conversations Creates a Mandate for Change

Our experience in virtually all SFP applications, even those that were ultimately less successful, is that senior teams and task forces experience SFP as powerful emotionally. This is particularly true in organizations with deep performance and organizational alignment issues, and where people in the organization have lost hope that senior management will lead mean-ingful change.

Our interviews with senior teams across many organizations find that they report the same issues that they later hear from their task force. They know the issues and almost always say that they did not hear anything new. Nevertheless, the candor and directness of the task force puts them in touch emotionally with external and particularly internal realities from which they may have distanced themselves. For the first time they learn about how people at lower levels experience working in the organization and how its dynamics are undermining effectiveness. Consider the following quotes from SRSD’s general manager and senior team member:

I had known that there were some serious issues in the division that needed to be addressed. But when these problems were spelled out in detail to me and the staff by a group of employees, the situation took on a whole new light (SRSD’s general manager).

I was taking a lot of notes, but all I could think of the whole time was how did it get this bad?’ The discussion between the top team and how we worked together was even more painful. The whole thing was easily the worst day of my HP career. In my room at night I was considering writing a resignation letter, until I realized that Scott (the general manager) probably would not accept it. It hit me that we were in it up to our necks now and there was no turning back(SRSD senior team member).

the senior team does not. That the senior team is willing to expose themselves to what the task force sees as ‘‘brutal’’ feedback lifts hope that ‘‘this time’’ change will occur. And senior teams are moved to action by the experience of hearing the unvarnished truth. Consider how a senior team member in a U.K. corporation responded to unvarnished truth that was not new to him:

At the time I do not recall thinking any of this was earth shattering, but what I did think it said was there was a great need to get on with the things we have to do. We were seen as a soft, slow moving organization and the task force wanted us to get on with some pace. They would like strong leadership and for us to be a bit bolder. I think what we heard also validated that it was right to [have arranged for the task force to] talk with the leadership group.

SFP Leads to a Systemic Analysis of the Organization

The unstructured nature of the interviews – ‘‘does the strategic direction make sense?’’ ‘‘What are the strengths and barriers to implementing our strategic direction?’’ – allows task forces to identify a broad array of substantive issues that are perceived to undermine effectiveness. The silent killers described earlier reflect problems with the strategy or its communication (unclear strategy), leader and leadership team effectiveness, organization design (poor coordination), strategic management (conflicting priorities and resource allocation), human resource issues connected to identifying, evaluating, and developing leaders, and cultural issues with regard to openness and collaboration. This enables senior teams to develop a comprehensive diagnosis of the organization and a systemic action plan that fits the diagnosis. Hewlett Packard’s Santa Rosa Systems Division (see illustrative case above), the organization where SFP catalyzed the most dramatic changes (SeeFig. 4), provides an example of what is possible. Consider the change plan the senior team formulated:

The senior team had an open discussion about its ineffectiveness and

adopted a new meeting structure, norms, and ground rules for decision making.

Scott, the general manger learned that his conflict aversion was harming

team effectiveness and made changes in the role he would play in leading the senior team.

A radical redesign of the organization was made from a functional form

Custom Systems – SRSD’s applicationengineering group– and R&D were

combined into one functional department to make it easier to allocate engineering resources to the highest priority projects, a major cause of the cold war.

Having come to the realization that business teams had to be led by

individuals with a general management perspective and more experience than the engineering managers they had assigned to this role, senior team members decided to ‘‘double hat’’ themselves. Four took leadership of one of the four businesses in addition to their functional role.

The strategic management process – strategic planning and budgeting,

business reviews, and decisions about priorities, as well as allocation of financial and human resources – was redesigned.

SFP was adopted as an annual learning and governance process and was

integrated into the annual planning process.

The quotes from SRSD managers below illustrate how organizational members saw the changes that occurred. Note that changes in roles, respon-sibilities, decision rights, accountabilities, business processes, and rules of engagement (first quote) are far faster than changes in leadership behavior

(second quote). These take time and may require focused interventions and learning mechanisms that build capabilities, although this did not occur in SRSD and judging by SRSD’s success after SFP these were not needed:

What was really important was that we really understood what the process was trying to do – that is aligning the different parts of the organization. I think that the alignment we now have after the reorganization is both accurate and necessary for us to become an effective organization. In the small systems business that we have, there is no way of getting around the matrix structure. In the past there was no clear level of top management responsibility and ownership for key decision-makingyThat is something that is vital for strategic success of SRSD and it is something that the matrix is able to provide (A middle level production manager 1 year after SFP).

Our top team has taken some big strides in becoming more effective. Scott [GM] looks to be taking more control of the reins and becoming the kind of leader the division needs. He and his staff will sit down as a group now and talk strategy where before they would have only talked about administrative detail. But they are still not where they want to be as a team. They still seem to be having a tough time getting together and really coming to agreement over some tough and pressing issues. I think people in SRSD wanted and overnight change in the top team’s behavior. But, realistically, most good teams are not made in a day. They will have to work at it(Task force member 2 years after SFP).

The features of SFP that enable systemic change are enumerated below:

SFP requires the senior team to conduct a diagnosis – to agree on what

they heard and to identify root causes – first as individuals in an overnight assignment and then as a group on the second day of the three-day Fitness Meeting.

Senior teams are provided expert resources in the form of a causal map of

the territory and consultants who bring a systemic perspective and capabilities to help them work their way through a variety of issues. Consistent with process consultation principles, however, consultants frame problems and suggest alternative solutions. They do not offer recommendations. If consultants do not possess needed expertise, they help find them.

SFP Develops a Partnership and Commitment to Change

The work of the employee task force did was extremely impressive. They operated much like a professional consulting firm, except unlike consultants they were part of the organization and knew it inside out. (SRSD General Manager)

I think just the increased amount of time working with them [top team] increases communication. So I feel more comfortable talking to any of the people on the senior team. (SRSD Task Force Member)

Because SFP is designed to create a dialogue about what stands in the way of business success, senior teams are moved to act by the SFP process. They become bolder (as illustrated by an earlier quote), more aggressive in planning change. That is true in virtually all cases regardless of the ultimate extent of change over time. Said differently, SFP creates commitment to think systemically and aggressively about realignment of the organization, but sustainability depends on several conditions discussed later. The following quote by a senior team member in SRSD illustrates how a partnership and commitment develops:

The task force feedback really served several important roles. Not only did it function as a powerful tool to communicate difficult issues, but it also showed that the top team cared about what employees thought and that we would not institute a change process without asking for their input. Also I believe that by asking for their ‘‘unvarnished’’ opinions, the employees realized just how serious we were about improving SRSD’’s effectiveness. To Scott’s (general manager) credit, he probably took the most amount of risk initiating a process like this. He acted as the linchpin, and without his involvement, a process like this would have been spinning its wheels. (SRSD senior team member)

Commitment to change is developed in task force members as well. They are partnering with the senior team in solving strategic problems. Moreover, task forces view SFP as a once in a life time opportunity to improve the organization’s functioning and commit themselves to doing a thorough job of collecting data and feeding back the truth. The following quote from a corporate level task force member is illustrative:

The whole process was very cathartic and quite energizing. Most task force members knew at least a few of the other members and we came together and clicked into a sense of openness and trust. There was nothing held back when we were together as a group. We felt we had been handed an important responsibility and we wanted to do it justice. The process and the group seemed to be very good at encapsulating the essence of what we learned rather than getting caught up in any individual’s hobbyhorse.

Exposure to other departments – task force members’ interview outside their own department – develops a general management perspective. Task force members cease seeing the problem as that of another department and begin to see them as the organization’s, thus becoming committed to improving the system rather than blaming. A task force member from R&D noted that ‘‘when I started into my interviews I thought that marketing was the problem but now I think we in R&D may be the problem.’’ Our objective was to create a strong partnership between the senior team and task force members. As their best leaders in the organization such a partnership was important practically and symbolically. Steps 7 and 8 of SFP – task force members offer a critique of the senior team’s action plan and are invited to participate in revising the plan – are designed to do this (see Fig. 1and Appendix). Until we redesigned these steps to enable task force members to meet alone and discuss their critique as a group, they did not speak their minds forcefully or not at all during this critique phase. After the redesign exchanges were more spirited, change plans became better and stronger partnership developed. For example, the CEO of a company was told that a major issue – taking out a layer of management – had not been dealt with in the action plan. The action plan was revised and partnership and commitment grew.

Task force critiques can be emotionally difficult for leaders and senior teams heavily invested in their plans after hours of intensive work in the three-day Fitness Meeting. SRSD’s general manager recalled his feelings after the task force disagreed vehemently with how the senior team had grouped products into businesses.

The task force’s reaction to the business groupings literally felt like it took the wind out of the sails of my team. My staff and I worked for almost a half a day on just those groupings alone and finally felt that we had come up with the best possible options. I think it would not be an exaggeration when I say that hearing the task force criticize the groupings as well as other parts of our recommendations made for one of the worst days of in my career at HP. What seemed to make matters worse was that the task force didn’t seem to be offering up any better solutions. They were just playing the part of critics. I knew that I was going to have to do something rather quickly to alter their perspective; otherwise we were never going to receive their support for the change.

force member about why SRSD’s task force was not offering an alternative organizational solution the general manager requested, he responded:

Up until somewhere around 11:00 this morning, we were supposed to be just reporters; now we are expected to be co-change architects in this process. That is a tough transition that requires a lot of trust. There is a tremendous sense of risk in telling the boss how the company should be run, and think there is quite a few in the task force that are uncomfortable with doing that.

General managers had to find a way to validate employee partnership and build commitment by involving task force members in revising the action plan. The general manager of SRSD created three working groups composed of senior team members and task force members to develop alternatives. From this partnership a better solution to which everyone was committed developed. Task forces had to lean to interact with the senior team in solving difficult managerial problems. They had to take risks, speaking up and interacting in a less structured environment than that offered by the fishbowl. We have learned steps 7 and 8 of SFP are particularly powerful in creating partnership if managed well. Most leaders require some guidance from consultants.

Partnership with and commitment from the larger circle of 100 plus interviewees begins in steps 4C of SFP (see Appendix). After completing their feedback to senior teams and leaving the Fitness Meeting, each task force member calls the people they interviewed about what happened when the unvarnished truth was delivered. They are instructed to tell them how the senior team responded to feedback (were they receptive or defensive?) not the substance of the feedback (that comes later). Because SFP is designed to prevent defensiveness and develop collaboration, task force members can report that the senior team was nondefensive and heard the truth and began a collaboration to improve the organization – a communication that reduces cynicism and builds hope and commitment.

Leader and Leadership Teams Develop

Doubts about leadership effectiveness are pervasive in organizations, which is why leadership is almost always one of the silent barriers. Consider this view inside one of the corporations that undertook SFP.

There were some big question marks around the leadership, how the leadership was culpable for a lot of things that had gone wrong in the past. People talked about the Allied deal, the halving of the stock price, the big price we paid for [a company] only to sell it a few years later for much less. They also talked about how these people survived atyeven though they had made those mistakes. Then they look at the annual report and see these executives still got their bonuses. How can this be the leadership to take us forward?

The fact that leaders and senior team members learn about their effectiveness provides an opportunity for individual and senior team development. We have learned that it is important to allow space for that development, provided the leader and his/her team are ready. The more senior teams develop trust and become effective the more the organiza-tional transformation gains momentum. The data in Fig. 4 support this conclusion. Extent of change is strongly associated with extent of change in the silent killers. The general manager/CEO’s openness to learning determines the amount of personal and leadership development, not to speak of increases in their legitimacy. In the least successful applications of SFP the leaders made changes in strategy, organizational design, or the strategic management process, but failed to develop their leadership team or adapt their leadership style.

Task force members also develop as leaders. A task force member in SRSD opined that ‘‘the opportunity to participate in SFP was the best management development experience he had had in 20 years in the company.’’ As noted earlier, exposure to other parts of the organization develops a general management perspective. Participation also exposes task force members to values and leadership principles embedded in the process as well as practice in listening and dialogue.

Changes in Organizational Outcomes and Performance

developed inductively from the cases. Of these the following nine changed substantially:

1. Changes in how the business was organized and managed improved alignment with strategy.

2. Leaders embraced the basic principles and values underlying SFP. 3. Managers learned and developed (leader, senior team, and task force

members).

4. Significant progress was made in becoming a listening and learning culture.

5. The capacity of the organization was improved to implement its strategic tasks.

6. Human outcomes such as morale, attractiveness of the organization to recruits, and retention improved.

7. Organization made significant progress in overcoming barriers to performance such as coordination and commitment.

8. The top team created the context for ongoing action learning. 9. Performance accountability was significantly strengthened.

Hewlett Packard’s SRSD, the most affected of the 12 organizations, is illustrative of the changes SFP fosters. Its transformation from a functional to matrix organization dramatically improved coordination between func-tions around four businesses. The redefinition of the top team’s role in reviewing the businesses, setting priorities, and reallocating resources improved strategic management and accountability. And their decision to integrate SFP with their strategic management process meant that the leadership team embraced the principles and values of SFP – giving people voice and engaging them in ongoing learning and change. Without help from consultants, they also adapted the SFP process to improve coordination and collaboration with a sector sales force.

SFP can create very rapid change. SRSD’s senior team fundamentally redesigned its organization in two days and enacted the changes three months after SFP was launched. The power of the truth, seeing and acting on the system as a whole, and concentrated three days of work by the senior team achieved these rapid changes. HP’s Executive Vice President of Test and Measurement saw dramatic changes in SRSD’s business performance from his position two levels above the business unit.